The New Favela Beat - christopher reardon

The New Favela Beat - christopher reardon

The New Favela Beat - christopher reardon

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

THE NEW GLOBAL CITY<br />

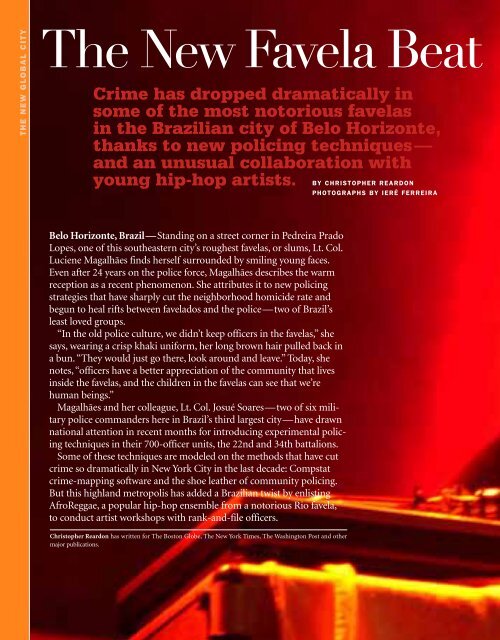

<strong>The</strong> <strong>New</strong> <strong>Favela</strong> <strong>Beat</strong><br />

Crime has dropped dramatically in<br />

some of the most notorious favelas<br />

in the Brazilian city of Belo Horizonte,<br />

thanks to new policing techniques—<br />

and an unusual collaboration with<br />

young hip-hop artists. BY CHRISTOPHER REARDON<br />

PHOTOGRAPHS BY IERÊ FERREIRA<br />

Belo Horizonte, Brazil—Standing on a street corner in Pedreira Prado<br />

Lopes, one of this southeastern city’s roughest favelas, or slums, Lt. Col.<br />

Luciene Magalhães finds herself surrounded by smiling young faces.<br />

Even after 24 years on the police force, Magalhães describes the warm<br />

reception as a recent phenomenon. She attributes it to new policing<br />

strategies that have sharply cut the neighborhood homicide rate and<br />

begun to heal rifts between favelados and the police—two of Brazil’s<br />

least loved groups.<br />

“In the old police culture, we didn’t keep officers in the favelas,” she<br />

says, wearing a crisp khaki uniform, her long brown hair pulled back in<br />

a bun. “<strong>The</strong>y would just go there, look around and leave.” Today, she<br />

notes, “officers have a better appreciation of the community that lives<br />

inside the favelas, and the children in the favelas can see that we’re<br />

human beings.”<br />

Magalhães and her colleague, Lt. Col. Josué Soares—two of six military<br />

police commanders here in Brazil’s third largest city—have drawn<br />

national attention in recent months for introducing experimental policing<br />

techniques in their 700-officer units, the 22nd and 34th battalions.<br />

Some of these techniques are modeled on the methods that have cut<br />

crime so dramatically in <strong>New</strong> York City in the last decade: Compstat<br />

crime-mapping software and the shoe leather of community policing.<br />

But this highland metropolis has added a Brazilian twist by enlisting<br />

AfroReggae, a popular hip-hop ensemble from a notorious Rio favela,<br />

to conduct artist workshops with rank-and-file officers.<br />

Christopher Reardon has written for <strong>The</strong> Boston Globe, <strong>The</strong> <strong>New</strong> York Times, <strong>The</strong> Washington Post and other<br />

major publications.

At the invitation of Belo<br />

Horizonte’s 34th police<br />

battalion, a D.J. from<br />

the rap group NUC participated<br />

in a weeklong<br />

workshop designed to<br />

break down barriers<br />

between police and<br />

slum-dwelling youth.

<strong>The</strong>se innovations, supported by the Ford Foundation, are<br />

reaping rewards among the 2.3 million residents of Belo Horizonte,<br />

the capital of Minas Gerais state. For more than two decades, this<br />

state has pioneered new approaches to law enforcement.<br />

Such reforms are rare in Brazil, where the military police<br />

(who patrol the nation’s streets) and the civil police (who investigate<br />

crimes) maintain a pattern of repressive tactics and human<br />

rights abuses. In April, eight rogue officers in Rio de Janeiro<br />

were charged with murdering 30 favela residents in a shooting<br />

spree earlier this year. <strong>The</strong> aggressive police culture is widely<br />

Partners in Crime-Fighting<br />

<strong>The</strong> Ford Foundation’s support for police reform in Brazil<br />

reflects a commitment to strengthening that nation’s<br />

criminal justice system, a pillar of any democratic society.<br />

<strong>The</strong> AfroReggae Cultural Group, the Center for Studies on<br />

Public Security and Citizenship and the Center for Crime<br />

and Public Safety Studies advance this effort by showing<br />

that civil society can play an important role in helping<br />

police institutions become more responsive, effective<br />

and accountable to the public.<br />

viewed as a legacy of the dictatorship that ruled until the early<br />

1980’s, when the nation began a transition to democracy. Some<br />

critics trace the problems further back.<br />

“If you look back to the 19th century, the police were created<br />

in Brazil to protect slaveowners, not slaves,” notes Claudio<br />

<strong>Beat</strong>o, a policing expert at the Federal University of Minas<br />

Gerais.“In practical terms, their function was to fight poor people<br />

and protect rich people.” Some of the city’s policing reforms<br />

originated at the university’s Center for Crime and Public Safety<br />

Studies, a research institute that <strong>Beat</strong>o directs. <strong>The</strong> center (known<br />

by its Portuguese acronym, CRISP) has a staff of 36, with expertise<br />

in such fields as demography, spatial analysis, statistics, computer<br />

science, economics and sociology.<br />

“One of the problems in Brazil is the absence of good information<br />

about crime and violence,” says <strong>Beat</strong>o. “At CRISP, we’re<br />

working to help the military police take a more sophisticated<br />

approach. It’s easier to respond to crimes, and prevent them,<br />

when you know exactly where they tend to occur.”<br />

In the last six years, hundreds of officers have taken courses<br />

at the university in human rights, statistics, administration and<br />

related fields. Meanwhile, CRISP has helped military police set<br />

up a crime-mapping and analysis program, using computers<br />

Silvia Ramos, area<br />

coordinator at Brazil’s<br />

Center for Studies on<br />

Public Security and<br />

Citizenship (fourth from<br />

left), and members of<br />

the AfroReggae Cultural<br />

Group, with officers<br />

from Belo Horizonte’s<br />

22nd battalion after<br />

a workshop.<br />

20 Ford Foundation Report Spring/Summer 2005

Police officers and graffiti artists<br />

took a walk in each others’ shoes<br />

during a workshop created by<br />

AfroReggae and Belo Horizonte<br />

police department reformers.<br />

to plot the incidence of crime block by<br />

block, month by month. When the system<br />

was applied in Pedreira Prado Lopes,<br />

<strong>Beat</strong>o says, the homicide rate among its<br />

10,000 residents plummeted from the<br />

staggeringly high figure of 56 in the first<br />

nine months of last year.<br />

Data and aerial photographs showed<br />

that many shootings had taken place at<br />

the same intersection where Magalhães<br />

recently got friendly greetings. Police<br />

replaced an adjacent fence and trimmed<br />

nearby trees that had provided cover for<br />

assailants. A specially trained unit then<br />

arrested the most dangerous gang leaders<br />

and brokered a truce between their<br />

successors. In the three months that followed,<br />

only two homicides occurred there.<br />

In 2002, CRISP also had a hand in<br />

launching a successful homicide-reduction<br />

program, Fica Vivo! (Stay Alive!), in<br />

another favela with a high crime rate. A<br />

public-private partnership that originated<br />

in Soares’ battalion, this program was<br />

modeled in part on a highly successful cease-fire program brokered<br />

by clergy in Boston, Mass., seven years earlier. It has since<br />

expanded to 21 regions in Minas Gerais. Youth centers are a<br />

key feature, offering constructive alternatives to gang culture.<br />

<strong>The</strong> reforms hardly guarantee success, however. Crack cocaine<br />

is fueling a violent crime wave; citywide, homicides rose 9.8<br />

percent last year. But in neighborhoods patrolled by the battalions<br />

that embrace the new<br />

strategies most ardently,<br />

Soares says, homicides fell 25<br />

percent last year.<br />

Belo Horizonte sits on a<br />

high plain with striking alpine<br />

views. But despite its name,<br />

which means “beautiful horizon,”<br />

the city is a patchwork<br />

of privilege and poverty. Leafy<br />

streets lined with gated compounds<br />

adjoin makeshift<br />

communities where slum<br />

dwellers tap into municipal<br />

water and electrical supplies.<br />

At least 25 percent of the population lives in nearly 100 favelas,<br />

spreading steadily up the slopes of the Corral Mountains.<br />

Some are havens for heavily armed gangs controlling the<br />

drug trade, which has underpinned violent crime over the last<br />

two decades. From 1986 to 2004, for every 100,000 city residents,<br />

armed robberies soared from 97.3 to 422 and homicides<br />

climbed from 8.4 to 44.8.<br />

Yet these incidents are highly localized. <strong>The</strong> vast majority of<br />

<strong>The</strong> 23-year police veteran figured he’d<br />

mastered the tools of his trade: a twoway<br />

radio, handcuffs and a 9-millimeter<br />

service pistol. He never imagined that<br />

one day he’d add a bass drum or a can<br />

of spray paint.<br />

homicides occur within favelas, and most robberies take place<br />

a block or two outside. Moreover, a recent study found that 20<br />

percent of violent crime takes place in just six favelas. “People<br />

talk about an explosion of violence,” says <strong>Beat</strong>o. “Really it’s an<br />

implosion. It’s very focused in a few poor neighborhoods.”<br />

Officials like Magalhães and Soares are helping to make the<br />

police more responsive to crime data, more intent on preventing<br />

crimes and more accountable to the public—particularly<br />

to favelados. Two years ago, Soares introduced special units<br />

devoted to high-risk areas in the 22nd battalion. Now such units<br />

have spread to the 34th battalion and beyond.<br />

Soares, a plainspoken man wearing a black beret, says, “Not<br />

long ago, a lot of officers believed we had to use force to stop<br />

criminality. Our mentality has changed in the way we approach<br />

favelados.” <strong>The</strong> 23-year police veteran figured he’d mastered<br />

Ford Foundation Report Spring/Summer 2005 21

Police officers from<br />

the 34th battalion’s<br />

percussion group have<br />

added drums to their<br />

crime-stopping arsenal.<br />

the tools of his trade: a two-way radio, handcuffs and a 9-millimeter<br />

service pistol. He never imagined that one day he’d add<br />

a bass drum or a can of spray paint.<br />

<strong>The</strong>n last year, local officials got wind of an idea from Rio:<br />

AfroReggae, a hip-hop group from Vigário Geral (a favela so<br />

notorious it’s known simply as V.G.), proposed a series of artist<br />

residencies to ease tensions between young people and the<br />

police. <strong>The</strong> project failed to gain traction in Rio, but the Secretariat<br />

of Social Defense in Minas Gerais state offered to bring<br />

it to Belo Horizonte.<br />

<strong>The</strong> 22nd and 34th battalions enlisted<br />

AfroReggae to lead four weeklong<br />

encounters designed to dispel stereotypes<br />

that divide police and favelados. Band<br />

members trained officers in drumming,<br />

dancing, graffiti, video and circus arts. At<br />

two concerts, slum residents mingled with<br />

hundreds of officers and their families.<br />

<strong>The</strong> workshops build on the “peace artists”programs of recent<br />

years, in which hundreds of officers coach soccer or give music<br />

lessons in the favelas. <strong>The</strong>y seek to drive a wedge between criminal<br />

gangs and the law-abiding majority.<br />

<strong>Beat</strong>o calls the AfroReggae workshops “one of the most interesting<br />

processes of police reform in Latin America.”<strong>The</strong>y help, he<br />

adds, by “changing the misperceptions that keep police officers<br />

and young people from the slums locked in a tense relationship.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> band formed in 1993 after police gunned down 21<br />

bystanders in Vigário Geral. Coming just weeks after police<br />

killed eight street children sleeping on the steps of a historic<br />

church, the incident made headlines worldwide. It inspired José<br />

Júnior, a young D.J. who made ends meet by driving a taxi, to<br />

‘<strong>The</strong> sound you heard before was<br />

the sound of guns. Now what you<br />

hear is music.’<br />

join friends in launching AfroReggae, a loose ensemble of percussionists,<br />

guitarists, turntablists and vocalists who write<br />

bouncy, popular songs about hope and survival.<br />

“We wanted to take V.G. out of the headlines about violence<br />

and put it in the culture section of the newspaper,” says Júnior.<br />

22 Ford Foundation Report Spring/Summer 2005

Toni Garrido, a Brazilian<br />

pop star, left, joined<br />

AfroReggae’s Luiz<br />

Gustavo in a concert<br />

at Belo Horizonte’s<br />

34th police battalion.<br />

“<strong>The</strong> sound you heard before was the sound of guns. Now what<br />

you hear is music.”<br />

More than a band, the AfroReggae Cultural Group is a registered<br />

nongovernmental organization that runs youth centers<br />

in V.G. and another favela near the sands of Ipanema. Hundreds<br />

of adolescents spend afternoons making music and practicing<br />

circus tricks, and some start their own ensembles.<br />

Paulo Neguéba, a percussionist who led the police workshops<br />

in Belo Horizonte, is living proof that the band takes its message<br />

to heart. Driving through V.G. two years ago, he was caught<br />

in the crossfire of a police operation gone awry. He took four<br />

bullets in his legs and back, two other bystanders were injured<br />

and a third was killed in the assault, which resulted in the firing<br />

of the police commander.<br />

“At first I felt angry, like anyone would,” recalls Neguéba, who<br />

underwent three operations and months of physical therapy.<br />

“But now I have a broader perspective. I cannot combat evil<br />

with more evil.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> AfroReggae workshops yielded striking scenes of Belo<br />

Horizonte’s police creating music and art with rappers from<br />

Rio’s most notorious favela. <strong>The</strong>se new experiences changed<br />

the way police and youth see one another, how they see themselves<br />

and how they are seen by the larger society, says Silvia<br />

Ramos of the Center for Studies on Public Security and Citizenship.<br />

<strong>The</strong> center, based at Candido Mendes University in Rio,<br />

helped administer and document the workshops.<br />

“I’m always looking for tools that can change police behavior<br />

and attitudes,”says Ramos, who holds a doctorate in psychology.<br />

“I used to give them classes and lectures about respecting<br />

the human rights of the poor population, but that language<br />

wasn’t working. It created resistance and defensiveness. This<br />

project is much more powerful. It reaches them, not just through<br />

their minds, but in their hearts and in their bodies.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> workshops made headlines nationwide and soon will<br />

reach a wider audience through a photographic exhibit, a book<br />

and a television documentary. Moreover, there are plans to expand<br />

the program to all six battalions in Belo Horizonte this year, with<br />

additional support from the state government. This time,AfroReggae<br />

will be joined by local dance and drumming groups.<br />

As Lt. Cláudio Alves da Silva, a tactical officer in the 22nd<br />

battalion, observes, “Before we started these social programs,<br />

people in the favelas saw us as a major enemy. <strong>The</strong>y would shoot<br />

down into the battalion from the hillside.” He adds,“Now when<br />

we enter the favelas we get a good reaction.” <br />

Ford Foundation Report Spring/Summer 2005 23