The New Favela Beat - christopher reardon

The New Favela Beat - christopher reardon

The New Favela Beat - christopher reardon

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>The</strong>se innovations, supported by the Ford Foundation, are<br />

reaping rewards among the 2.3 million residents of Belo Horizonte,<br />

the capital of Minas Gerais state. For more than two decades, this<br />

state has pioneered new approaches to law enforcement.<br />

Such reforms are rare in Brazil, where the military police<br />

(who patrol the nation’s streets) and the civil police (who investigate<br />

crimes) maintain a pattern of repressive tactics and human<br />

rights abuses. In April, eight rogue officers in Rio de Janeiro<br />

were charged with murdering 30 favela residents in a shooting<br />

spree earlier this year. <strong>The</strong> aggressive police culture is widely<br />

Partners in Crime-Fighting<br />

<strong>The</strong> Ford Foundation’s support for police reform in Brazil<br />

reflects a commitment to strengthening that nation’s<br />

criminal justice system, a pillar of any democratic society.<br />

<strong>The</strong> AfroReggae Cultural Group, the Center for Studies on<br />

Public Security and Citizenship and the Center for Crime<br />

and Public Safety Studies advance this effort by showing<br />

that civil society can play an important role in helping<br />

police institutions become more responsive, effective<br />

and accountable to the public.<br />

viewed as a legacy of the dictatorship that ruled until the early<br />

1980’s, when the nation began a transition to democracy. Some<br />

critics trace the problems further back.<br />

“If you look back to the 19th century, the police were created<br />

in Brazil to protect slaveowners, not slaves,” notes Claudio<br />

<strong>Beat</strong>o, a policing expert at the Federal University of Minas<br />

Gerais.“In practical terms, their function was to fight poor people<br />

and protect rich people.” Some of the city’s policing reforms<br />

originated at the university’s Center for Crime and Public Safety<br />

Studies, a research institute that <strong>Beat</strong>o directs. <strong>The</strong> center (known<br />

by its Portuguese acronym, CRISP) has a staff of 36, with expertise<br />

in such fields as demography, spatial analysis, statistics, computer<br />

science, economics and sociology.<br />

“One of the problems in Brazil is the absence of good information<br />

about crime and violence,” says <strong>Beat</strong>o. “At CRISP, we’re<br />

working to help the military police take a more sophisticated<br />

approach. It’s easier to respond to crimes, and prevent them,<br />

when you know exactly where they tend to occur.”<br />

In the last six years, hundreds of officers have taken courses<br />

at the university in human rights, statistics, administration and<br />

related fields. Meanwhile, CRISP has helped military police set<br />

up a crime-mapping and analysis program, using computers<br />

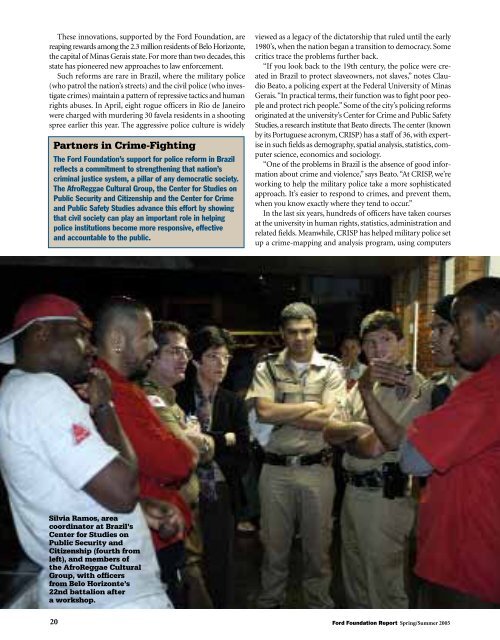

Silvia Ramos, area<br />

coordinator at Brazil’s<br />

Center for Studies on<br />

Public Security and<br />

Citizenship (fourth from<br />

left), and members of<br />

the AfroReggae Cultural<br />

Group, with officers<br />

from Belo Horizonte’s<br />

22nd battalion after<br />

a workshop.<br />

20 Ford Foundation Report Spring/Summer 2005