A Roadmap to Michigan's Future - Millennium Project - University of ...

A Roadmap to Michigan's Future - Millennium Project - University of ...

A Roadmap to Michigan's Future - Millennium Project - University of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Enterprise Systems<br />

R&D Outsourcing<br />

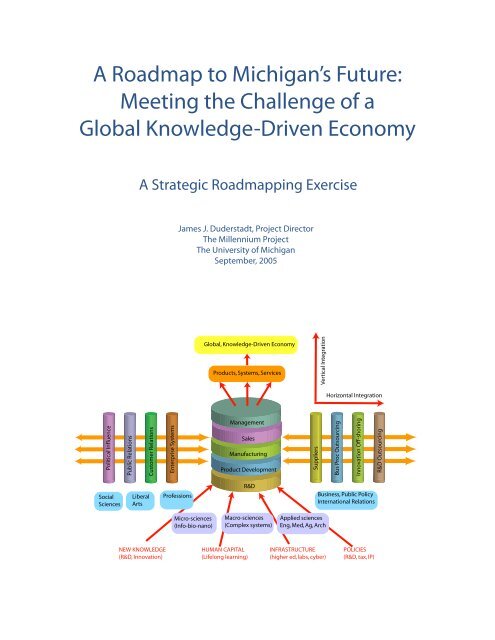

A <strong>Roadmap</strong> <strong>to</strong> Michigan’s <strong>Future</strong>:<br />

Meeting the Challenge <strong>of</strong> a<br />

Global Knowledge-Driven Economy<br />

A Strategic <strong>Roadmap</strong>ping Exercise<br />

James J. Duderstadt, <strong>Project</strong> Direc<strong>to</strong>r<br />

The <strong>Millennium</strong> <strong>Project</strong><br />

The <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Michigan<br />

September, 2005<br />

Global, Knowledge-Driven Economy<br />

Products, Systems, Services<br />

Vertical Integration<br />

Horizontal Integration<br />

Political Influence<br />

Public Relations<br />

Cus<strong>to</strong>mer Relations<br />

Management<br />

Sales<br />

Manufacturing<br />

Product Development<br />

Suppliers<br />

Bus Proc Outsourcing<br />

Innovation Off-shoring<br />

Social<br />

Sciences<br />

Liberal<br />

Arts<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essions<br />

R&D<br />

Business, Public Policy<br />

International Relations<br />

Micro-sciences<br />

(Info-bio-nano)<br />

Macro-sciences<br />

(Complex systems)<br />

Applied sciences<br />

Eng, Med, Ag, Arch<br />

NEW KNOWLEDGE<br />

(R&D, Innovation)<br />

HUMAN CAPITAL<br />

(Lifelong learning)<br />

INFRASTRUCTURE<br />

(higher ed, labs, cyber)<br />

POLICIES<br />

(R&D, tax, IP)

@ 2005 The <strong>Millennium</strong> <strong>Project</strong>, The <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Michigan<br />

All rights reserved.<br />

The <strong>Millennium</strong> <strong>Project</strong><br />

The <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Michigan<br />

2001 Duderstadt Center<br />

2281 Bonisteel Boulevard<br />

Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2094<br />

http://milproj.dc.umich.edu

Executive Summary<br />

Investing in human capital…and the future!<br />

Michigan’s old manufacturing economy is dying,<br />

slowly but surely, putting at risk the welfare <strong>of</strong> millions<br />

<strong>of</strong> citizens in our state in the face <strong>of</strong> withering competition<br />

from an emerging global knowledge economy. For<br />

many years now we have seen our low-skill, high-pay<br />

fac<strong>to</strong>ry jobs increasingly downsized, outsourced, and<br />

<strong>of</strong>fshored, only <strong>to</strong> be replaced by low-skill, low-pay service<br />

jobs–or in <strong>to</strong>o many cases, no jobs at all and instead<br />

the unemployment lines. Preoccupied with obsolete political<br />

battles, addicted <strong>to</strong> entitlements, and assuming<br />

what worked before will work again, Michigan <strong>to</strong>day is<br />

sailing blindly in<strong>to</strong> a pr<strong>of</strong>oundingly different future.<br />

Thus far our state has been in denial, assuming our<br />

low-skill workforce would remain competitive and our<br />

fac<strong>to</strong>ry-based manufacturing economy would be prosperous<br />

indefinitely. Yet that 20th-century economy will<br />

not return. Our state is at great risk, since by the time<br />

we come <strong>to</strong> realize the permanence <strong>of</strong> this economic<br />

transformation, the out-sourcing/<strong>of</strong>f-shoring train may<br />

have left <strong>to</strong>wn, taking with it both our low-skill manufacturing<br />

jobs and many <strong>of</strong> our higher-paying service<br />

jobs.<br />

Michigan is certainly not alone in facing this new<br />

economic reality. Yet as we look about, we see other<br />

states, not <strong>to</strong> mention other nations, investing heavily<br />

and restructuring their economies <strong>to</strong> create high-skill,<br />

high-pay jobs in knowledge-intensive areas such as<br />

new technologies, financial services, trade, and pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

and technical services. From California <strong>to</strong> North<br />

Carolina, Bangalore <strong>to</strong> Shanghai, there is a growing recognition<br />

throughout the world that economic prosperity<br />

and social well-being in a global knowledge-driven<br />

economy require public investment in knowledge<br />

resources. That is, regions must create and sustain a<br />

highly educated and innovative workforce, supported<br />

through policies and investments in cutting-edge technology,<br />

a knowledge infrastructure, and human capital<br />

development.<br />

Ironically, a century ago Michigan led the nation<br />

in building just such knowledge resources. It created<br />

a great education system aimed at serving all <strong>of</strong> its<br />

citizens, demonstrating a remarkable capacity <strong>to</strong> look<br />

<strong>to</strong> the future and a willingness <strong>to</strong> take the actions and<br />

make the investments that would yield prosperity and<br />

well-being for future generations. Yet <strong>to</strong>day this spirit<br />

<strong>of</strong> public investment for the future appears missing.<br />

Decades <strong>of</strong> failed public policies and inadequate investment<br />

now threaten the extraordinary educational<br />

and knowledge resources built through the vision<br />

and sacrifices <strong>of</strong> past generations. Ironically, at a time<br />

when the rest <strong>of</strong> the world has recognized that investing<br />

in education and knowledge creation is the key <strong>to</strong><br />

not only prosperity but, indeed, survival, <strong>to</strong>o many <strong>of</strong><br />

Michigan’s citizens and leaders, in both the public and<br />

private sec<strong>to</strong>r, have come <strong>to</strong> view such investments as a<br />

low priority, expendable during hard times. The aging<br />

baby boomer population that now dominates public<br />

policy in our state demands instead expensive health<br />

care, ever more prisons, homeland security, and reduced<br />

tax burdens, rather than investing in education,<br />

innovation, and the future.<br />

Beyond a commitment <strong>to</strong> educational opportunity,<br />

there is another key <strong>to</strong> economic prosperity: technological<br />

innovation. As the source <strong>of</strong> new products and<br />

services, innovation is directly responsible for the most<br />

dynamic sec<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>of</strong> the U.S. economy. Here our nation<br />

has a great competitive advantage, since our society is<br />

based on a highly diverse population, democratic values,<br />

and free-market practices. These fac<strong>to</strong>rs provide an

ii<br />

New Knowledge<br />

(Research)<br />

Human Capital<br />

(Education)<br />

Infrastructure<br />

(Facilities, Systems)<br />

Policies<br />

(Tax, IP, R&D)<br />

Innovation<br />

The Keys <strong>to</strong> Innovation<br />

National Priorities<br />

Economic Competitiveness<br />

National and Homeland Security<br />

Public health and social well-being<br />

Global Challenges<br />

Global Sustainability<br />

Geopolitical Conflict<br />

Opportunities<br />

Emerging Technologies<br />

Interdisciplinary Activities<br />

Complex, Large-scale Systems<br />

unusually fertile environment for technological innovation.<br />

Once again Michigan provided leadership in the<br />

20th century, first putting the world on wheels and then<br />

becoming the arsenal <strong>of</strong> democracy.<br />

However, his<strong>to</strong>ry has also shown that significant<br />

public investment is necessary <strong>to</strong> produce the essential<br />

ingredients for innovation <strong>to</strong> flourish: new knowledge<br />

(research), human capital (education), infrastructure<br />

(facilities, labora<strong>to</strong>ries, communications networks),<br />

and policies (tax, intellectual property). Other nations<br />

are beginning <strong>to</strong> reap the benefits <strong>of</strong> such investments<br />

aimed at stimulating and exploiting technological innovation,<br />

creating serious competitive challenges <strong>to</strong> American<br />

industry and business both in the conventional<br />

marketplace (e.g., Toyota) and through new paradigms<br />

such as the <strong>of</strong>f-shoring <strong>of</strong> knowledge-intensive services<br />

(e.g., Bangalore, Shanghai). Yet again, at a time when<br />

our competi<strong>to</strong>rs are investing heavily in stimulating<br />

the technological innovation <strong>to</strong> secure future economic<br />

prosperity, Michigan is missing in action, significantly<br />

under-investing its economic and political resources in<br />

planting and nurturing the seeds <strong>of</strong> innovation.<br />

Adequately supporting education and technological<br />

innovation is not just something we would like <strong>to</strong><br />

do; it is something we have <strong>to</strong> do. What is really at stake<br />

here is building Michigan’s regional advantage, allowing<br />

it <strong>to</strong> compete for prosperity, for quality <strong>of</strong> life, in an<br />

increasingly competitive world. In a knowledge-intensive<br />

society, regional advantage is not achieved through<br />

gimmicks such as lotteries and casinos. It is achieved<br />

through creating a highly educated and skilled workforce.<br />

It requires an environment that stimulates creativity,<br />

innovation, and entrepreneurial behavior. Specifically,<br />

it requires public investment in the ingredients<br />

<strong>of</strong> innovation–educated people and new knowledge.<br />

Put another way, it requires public purpose, policy, and<br />

investment <strong>to</strong> create a knowledge society competitive<br />

in a global economy.<br />

This study has applied the planning technique <strong>of</strong><br />

strategic roadmapping <strong>to</strong> provide a framework for the<br />

issues that Michigan must face and the commitments<br />

that we must make, both as individuals and as a state,<br />

<strong>to</strong> achieve prosperity and social well-being in a global<br />

knowledge economy. The roadmapping process was<br />

originally developed in the electronics industry and<br />

is applied frequently <strong>to</strong> major federal agencies such<br />

as the Department <strong>of</strong> Defense and NASA. Although<br />

sometimes cloaked in jargon such as environmental<br />

scans, resource maps, and gap analysis, in reality the<br />

roadmapping process is quite simple. It begins by asking<br />

where we are <strong>to</strong>day, then where we wish <strong>to</strong> be <strong>to</strong>morrow,<br />

followed by an assessment <strong>of</strong> how far we have<br />

<strong>to</strong> go, and finally concludes by developing a roadmap<br />

<strong>to</strong> get from here <strong>to</strong> there. The roadmap itself usually<br />

consists <strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> recommendations, sometimes divided<br />

in<strong>to</strong> those that can be accomplished in the near<br />

term and those that will require longer-term and sustained<br />

effort.<br />

By any measure, the assessment <strong>of</strong> Michigan <strong>to</strong>day is<br />

very disturbing. Our state is having great difficulty in<br />

making the transition from a manufacturing <strong>to</strong> a knowledge<br />

economy. In recent years we have led the nation in<br />

unemployment, and our leading city, Detroit, now ranks<br />

as the nation’s poorest. Furthermore, the out-migration<br />

<strong>of</strong> young people in search <strong>of</strong> better jobs is the fourth<br />

most severe among the states; our educational system<br />

is underachieving with one-quarter <strong>of</strong> Michigan adults<br />

without a high school diploma and only one-third <strong>of</strong><br />

Michigan <strong>to</strong>day: Still dependent on a fac<strong>to</strong>ry economy<br />

as illustrated by au<strong>to</strong>motive plant locations. (MDLEG)

iii<br />

at the graduate level. Beyond this goal, the state should<br />

commit itself <strong>to</strong> providing high-quality, cost-effective,<br />

and diverse educational opportunities <strong>to</strong> all <strong>of</strong> its citizens<br />

throughout their lives, since during an era <strong>of</strong> rapid<br />

economic change and market restructuring, the key <strong>to</strong><br />

employment security has become continual, lifelong<br />

education.<br />

Drastic cuts in state appropriations over the past<br />

five years are crippling the state’s public universities.<br />

high school graduates college-ready. Fewer than onequarter<br />

<strong>of</strong> Michigan citizens have college degrees. Although<br />

Michigan’s system <strong>of</strong> higher education is generally<br />

regarded as one <strong>of</strong> the nation’s finest, the erosion <strong>of</strong><br />

state support over the past two decades and most seriously<br />

over the past five years–with appropriation cuts<br />

<strong>to</strong> public universities ranging from 20% <strong>to</strong> 40%–has not<br />

only driven up tuition but put the quality and capacity<br />

<strong>of</strong> our public universities at great risk.<br />

More generally, for many years Michigan has been<br />

shifting public funds and private capital away from investing<br />

in the future through education, research, and<br />

innovation <strong>to</strong> fund instead short term priorities such as<br />

prisons while inacting tax cuts that have crippled state<br />

revenues. And all the while, as the state budget began<br />

<strong>to</strong> sag and eventually collapsed in the face <strong>of</strong> a weak<br />

economy, public leaders were instead preoccupied with<br />

fighting the old and increasingly irrelevant cultural<br />

and political wars (cities vs. suburbs vs. exurbs, labor<br />

vs. management, religious right vs. labor left). In recent<br />

years the state’s mot<strong>to</strong> has become “Eat dessert first; life<br />

is uncertain!” Yet what Michigan has really been consuming<br />

is the seed corn for its future.<br />

A vision for Michigan <strong>to</strong>morrow can best be addressed<br />

by asking and answering three key questions:<br />

1. What skills and knowledge are necessary for individuals<br />

<strong>to</strong> thrive in a 21st-century, global, knowledge-intensive<br />

society Clearly a college education has become manda<strong>to</strong>ry,<br />

probably at the bachelor’s level, and for many,<br />

2. What skills and knowledge are necessary for a population<br />

(workforce) <strong>to</strong> provide regional advantage in such a competitive<br />

knowledge economy Here it is important <strong>to</strong> stress<br />

that we no longer are competing only with Ohio, Ontario,<br />

and California. More serious is the competition from<br />

the massive and increasingly well-educated workforces<br />

in emerging economies such as India, China, and the<br />

Eastern Bloc. For such knowledge workers, there is little<br />

distinction between work and education, since rapid<br />

technological change in a global economy requires the<br />

continuous improvement <strong>of</strong> workforce skills.<br />

3. What level <strong>of</strong> new knowledge generation (e.g., R&D,<br />

innovation, entrepreneurial zeal) is necessary <strong>to</strong> sustain a<br />

21st-century knowledge economy, and how is this achieved<br />

Here it is increasingly clear that the key <strong>to</strong> global competitiveness<br />

in regions aspiring <strong>to</strong> a high standard <strong>of</strong><br />

living is innovation. And the keys <strong>to</strong> innovation are<br />

new knowledge, human capital, infrastructure, and<br />

forward-looking public policies. Not only must a region<br />

match investments made by other states and nations<br />

in education, R&D, and infrastructure, but it must<br />

The World<br />

UM, MSU<br />

The State<br />

Michigan Tomorrow<br />

A Digital “Catholepistimead” or “Society <strong>of</strong> Learning<br />

Cultural<br />

Universitas<br />

Colleges and Universities<br />

Gymnasia<br />

Schools<br />

Corporate R&D centers<br />

High tech startups<br />

Knowledge networks<br />

Families<br />

Cyberinfrastructure<br />

Michigan-Link<br />

Michigan Broadband<br />

Internet2, National Lamba Rail, etc.<br />

Digital Libraries<br />

Virtual Universities, Global Universities<br />

The Region (Great Lakes)<br />

UM, MSU<br />

The Nation<br />

Michigan <strong>to</strong>morrow: a knowledge economy

iv<br />

recognize the inevitability <strong>of</strong> new innovative, technology-driven<br />

industries replacing old obsolete and dying<br />

industries as a natural process <strong>of</strong> “creative destruction”<br />

(a la Schumpeter) that characterizes a hypercompetitive<br />

global economy.<br />

So how far does Michigan have <strong>to</strong> travel <strong>to</strong> achieve a<br />

knowledge economy competitive at the global level<br />

What is the gap between Michigan <strong>to</strong>day and Michigan<br />

<strong>to</strong>morrow This part <strong>of</strong> the roadmapping process does<br />

not require a rocket scientist. One need only acknowledge<br />

the hopelessness in the faces <strong>of</strong> the unemployed,<br />

or the backward glances <strong>of</strong> young people as they leave<br />

our state for better jobs, or the angst <strong>of</strong> students and<br />

parents facing yet another increase in college costs as<br />

state government once again cuts appropriations for<br />

higher education. To paraphrase Thomas Friedman,<br />

“The world is flat! Globalization has collapsed time and<br />

distance and raised the notion that someone anywhere<br />

on earth can do your job, more cheaply. Can Michigan<br />

rise <strong>to</strong> the challenge on this leveled playing field”<br />

So, what do we need <strong>to</strong> do What is the roadmap <strong>to</strong><br />

Michigan’s future In a knowledge-intensive economy,<br />

regional advantage in a highly competitive global marketplace<br />

is achieved through creating a highly educated<br />

and skilled workforce. It requires an environment that<br />

stimulates creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurial<br />

behavior. Experience elsewhere has shown that visionary<br />

public policies and significant public investments<br />

in high-skilled human capital, research and innovation,<br />

and infrastructure are necessary <strong>to</strong> sustain a knowledge<br />

economy.<br />

education from both public and private sources as well as significant<br />

changes in public policy. It will also likely require<br />

a dedicated source <strong>of</strong> tax revenues <strong>to</strong> achieve and secure the<br />

necessary levels <strong>of</strong> investment during a period <strong>of</strong> gridlock in<br />

state government, perhaps through a citizen-initiated referendum.<br />

This, in turn, will require a major effort <strong>to</strong> build<br />

adequate public awareness <strong>of</strong> the importance <strong>of</strong> higher education<br />

<strong>to</strong> the future <strong>of</strong> the state and its citizens.<br />

2. To achieve and sustain the quality <strong>of</strong> and access <strong>to</strong> educational<br />

opportunities, Michigan needs <strong>to</strong> move in<strong>to</strong> the <strong>to</strong>p<br />

quartile <strong>of</strong> states in its higher education appropriations (on<br />

a per student basis) <strong>to</strong> its public universities. To achieve this<br />

objective, state government should set a target <strong>of</strong> increasing<br />

by 30% (beyond inflation) its appropriations <strong>to</strong> its public<br />

universities over the next five years.<br />

3. The increasing dependence <strong>of</strong> the knowledge economy<br />

on science and technology, coupled with Michigan’s relatively<br />

low ranking in percentage <strong>of</strong> graduates with science and<br />

engineering degrees, motivates a strong recommendation <strong>to</strong><br />

state government <strong>to</strong> place a much higher priority on providing<br />

targeted funding for program and facilities support in<br />

these areas in state universities, similar <strong>to</strong> that provided in<br />

California, Texas, and many other states. In addition, more<br />

effort should be directed <strong>to</strong>ward K-12 <strong>to</strong> encourage and adequately<br />

prepare students for science and engineering studies,<br />

including incentives such as forgivable college loan programs<br />

in these areas (with forgiveness contingent upon completion<br />

<strong>of</strong> degrees and working for Michigan employers). In addition,<br />

The <strong>Roadmap</strong>: The Near Term (...now!...)<br />

For the near term our principal recommendations<br />

focus on changing policies for investing in higher education,<br />

research, and innovation, while providing our<br />

institutions with the capacity <strong>to</strong> become more agile and<br />

market-smart.<br />

Human Capital<br />

1. Michigan simply must increase the participation <strong>of</strong> its<br />

citizens in higher education at all levels–community college,<br />

baccalaureate, and graduate and pr<strong>of</strong>essional degrees. This<br />

will require a substantial increase in the funding <strong>of</strong> higher<br />

New engineering students

state government should strongly encourage public universities<br />

<strong>to</strong> recruit science and engineering students from other<br />

states and nations, particularly at the graduate level, perhaps<br />

even providing incentives if they accept employment following<br />

graduation with Michigan companies.<br />

4. Colleges and universities should place far greater emphasis<br />

on building alliances that will allow them <strong>to</strong> focus<br />

on unique core competencies while joining with other institutions<br />

in both the public and private sec<strong>to</strong>r <strong>to</strong> address the<br />

broad and diverse needs <strong>of</strong> society in the face <strong>of</strong> <strong>to</strong>day’s social,<br />

economic, and technological challenges while addressing<br />

the broad and diverse needs <strong>of</strong> society. For example, research<br />

universities should work closely with regional univerisities<br />

and independent colleges <strong>to</strong> provide access <strong>to</strong> cutting-edge<br />

knowledge resources and programs.<br />

New Knowledge (R&D, innovation)<br />

5. The quality and capacity <strong>of</strong> Michigan’s learning and<br />

knowledge infrastructure will be determined by the leadership<br />

<strong>of</strong> its public research universities in discovering new knowledge,<br />

developing innovative applications <strong>of</strong> those discoveries<br />

that can be transferred <strong>to</strong> society, and educating those capable<br />

<strong>of</strong> working at the frontiers <strong>of</strong> knowledge and the pr<strong>of</strong>essions.<br />

State government should strongly support the role <strong>of</strong> these<br />

institutions as sources <strong>of</strong> advanced studies and research by<br />

dramatically increasing public support <strong>of</strong> research infrastructure,<br />

analogous <strong>to</strong> the highly successful Research Excellence<br />

Fund <strong>of</strong> the 1980s. Also key will be enhanced support <strong>of</strong> the<br />

efforts <strong>of</strong> regional colleges and universities <strong>to</strong> integrate this<br />

new knowledge in<strong>to</strong> academic programs capable <strong>of</strong> providing<br />

lifelong learning opportunities <strong>of</strong> world-class quality while<br />

supporting their surrounding communities in the transition<br />

<strong>to</strong> knowledge economies.<br />

6. In response <strong>to</strong> such reinvestment in the research capacity<br />

<strong>of</strong> Michigan’s universities, they, in turn, must become<br />

more strategically engaged in both regional and statewide<br />

economic development activities. Intellectual property policies<br />

should be simplified; faculty and staff should be encouraged<br />

<strong>to</strong> participate in the startup and spin<strong>of</strong>f <strong>of</strong> high-tech<br />

business; and universities should be willing <strong>to</strong> invest some<br />

<strong>of</strong> their own assets (e.g., endowment funds) in state- and region-based<br />

venture capital activities. Furthermore, universities<br />

and state government should work more closely <strong>to</strong>gether<br />

<strong>to</strong> go after major high tech opportunities in both the private<br />

sec<strong>to</strong>r (attracting new knowledge-based companies) and federal<br />

initiatives).<br />

7. Michigan must also invest additional public and private<br />

resources in private-sec<strong>to</strong>r initiatives designed <strong>to</strong> stimulate<br />

R&D, innovation, and entrepreneurial activities. Key<br />

elements would include reforming state tax policy <strong>to</strong> encourage<br />

new, high-tech business development, securing sufficient<br />

venture capital, state participation in cost-sharing for federal<br />

research projects, and a far more aggressive and effective effort<br />

by the Michigan Congressional delegation <strong>to</strong> attract major<br />

federal research funding <strong>to</strong> the state.<br />

Infrastructure<br />

Ultra-high power laser labora<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

8. Providing the educational opportunities and new<br />

knowledge necessary <strong>to</strong> compete in a global, knowledge-driven<br />

economy requires an advanced infrastructure: educational<br />

and research institutions, physical infrastructure such as<br />

labora<strong>to</strong>ries and cyberinfrastructure such as broadband networks,<br />

and supportive policies in areas such as tax and intellectual<br />

property. Michigan must invest heavily <strong>to</strong> transform<br />

the infrastructure for a 20 th -century manufacturing economy<br />

in<strong>to</strong> that required for a 21 st -century knowledge economy. Of<br />

particular importance is a commitment by state government<br />

<strong>to</strong> provide adequate annual appropriations for university capital<br />

facilities comparable <strong>to</strong> those <strong>of</strong> other leading states. It is

vi<br />

also important for both state and local government <strong>to</strong> play a<br />

more active role in stimulating the development <strong>of</strong> pervasive<br />

high speed broadband networks, since experience suggests<br />

that reliance upon private sec<strong>to</strong>r telcom and cable monopolies<br />

could well trap Michigan in a cyberinfrastructure backwater<br />

relative <strong>to</strong> other regions (and nations).<br />

Policies<br />

9. As powerful market forces increasingly dominate public<br />

policy, Michigan’s higher-education strategy should become<br />

market-smart, investing more public resources directly<br />

in the marketplace through programs such as vouchers, needbased<br />

financial aid, and competitive research grants, while<br />

enabling public colleges and universities <strong>to</strong> compete in this<br />

market through encouraging greater flexibility and differentiation<br />

in pricing, programs, and quality aspirations.<br />

10. Michigan should target its tax dollars more strategically<br />

<strong>to</strong> leverage both federal and private-sec<strong>to</strong>r investment<br />

in education and R&D. For example, a shift <strong>to</strong>ward higher<br />

tuition/need-based financial aid policies in public universities<br />

not only leverages greater federal financial aid but also<br />

avoids unnecessary subsidy <strong>of</strong> high-income students. Furthermore<br />

greater state investment in university research capacity<br />

would leverage greater federal and industrial support<br />

<strong>of</strong> campus-based R&D.<br />

11. Key <strong>to</strong> achieving the agility necessary <strong>to</strong> respond <strong>to</strong><br />

market forces will be a new social contract negotiated between<br />

the state government and Michigan’s public colleges<br />

and universities, which provides enhanced market agility in<br />

return for greater (and more visible) public accountability<br />

with respect <strong>to</strong> quantifiable deliverables such as graduation<br />

rates, student socioeconomic backgrounds, and intellectual<br />

property generated through research and transferred in<strong>to</strong> the<br />

marketplace.<br />

economic prosperity, social well-being, and national<br />

security. Moreover, education, knowledge, innovation,<br />

and entrepreneurial skills have also become the primary<br />

determinants <strong>of</strong> one’s personal standard <strong>of</strong> living<br />

and quality <strong>of</strong> life. We believe that democratic societies–including<br />

state and federal governments–must<br />

accept the responsibility <strong>to</strong> provide all <strong>of</strong> their citizens<br />

with the educational and training opportunities they<br />

need, throughout their lives, whenever, wherever, and<br />

however they need it, at high quality and at affordable<br />

prices.<br />

To this end, the long-term roadmap proposes a vision<br />

<strong>of</strong> the future in which Michigan strives <strong>to</strong> build<br />

a knowledge infrastructure capable <strong>of</strong> adapting and<br />

evolving <strong>to</strong> meet the imperatives <strong>of</strong> a global, knowledge-driven<br />

world. Such a vision is essential <strong>to</strong> create<br />

the new knowledge (research and innovation), a skilled<br />

workforce, and the infrastructure necessary for Michigan<br />

<strong>to</strong> compete in the global economy while providing<br />

citizens with the lifelong learning opportunities and<br />

skills they need <strong>to</strong> live prosperous and secure lives in<br />

our state. As steps <strong>to</strong>ward this vision, we recommend<br />

the following actions:<br />

1. Michigan needs <strong>to</strong> develop a more systemic and strategic<br />

perspective <strong>of</strong> its educational, research, and cultural institutions–both<br />

public and private, formal and informal–that<br />

views these knowledge resources as comprising a knowledge<br />

ecology that must be allowed and encouraged <strong>to</strong> adapt and<br />

evolve rapidly <strong>to</strong> serve the needs <strong>of</strong> the state in a change driven<br />

world, free from micromanagement by state government<br />

or intrusion by partisan politics.<br />

The <strong>Roadmap</strong> (longer term...but within a decade...)<br />

For the longer term, our vision for the future <strong>of</strong><br />

higher education is shaped very much by the recognition<br />

that we have entered an age <strong>of</strong> knowledge in a<br />

global economy, in which educated people, the knowledge<br />

they produce, and the innovation and entrepreneurial<br />

skills they possess have become the keys <strong>to</strong><br />

Diverse institutions for diverse needs.

vii<br />

2. Michigan should strive <strong>to</strong> encourage and sustain<br />

a more diverse system <strong>of</strong> higher education, since institutions<br />

with diverse missions, core competencies, and funding<br />

mechanisms are necessary <strong>to</strong> serve the diverse needs <strong>of</strong> its<br />

citizens, while creating an knowledge infrastructure more resilient<br />

<strong>to</strong> the challenges presented by unpredictable futures.<br />

Using a combination <strong>of</strong> technology and funding policies, efforts<br />

should be made <strong>to</strong> link elements <strong>of</strong> Michigan’s learning,<br />

research, and knowledge resources in<strong>to</strong> a market-responsive<br />

seamless web, centered on the needs and welfare <strong>of</strong> its citizens<br />

and the prosperity and quality <strong>of</strong> life in the state rather than<br />

the ambitions <strong>of</strong> institutions and political leaders.<br />

3. Serious consideration should be given <strong>to</strong> reconfiguring<br />

Michigan’s educational enterprise by exploring new<br />

paradigms based on the best practices <strong>of</strong> other regions and<br />

nations. For example, the current segmentation <strong>of</strong> learning<br />

(e.g., primary, secondary, collegiate, graduate-pr<strong>of</strong>essional,<br />

workplace) is increasingly irrelevant in a competitive world<br />

that requires lifelong learning <strong>to</strong> keep pace with the exponential<br />

growth in new knowledge. More experimentation both in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> academic programs and institutional types should<br />

be encouraged.<br />

4. The quality and capacity <strong>of</strong> Michigan’s learning and<br />

knowledge infrastructure will be determined by the leadership<br />

<strong>of</strong> its two AAU-class research universities, UMAA and<br />

MSU, in discovering new knowledge, developing innovative<br />

applications <strong>of</strong> these discoveries that can be transferred <strong>to</strong> society,<br />

and educating those capable <strong>of</strong> working at the frontiers<br />

<strong>of</strong> knowledge and the pr<strong>of</strong>essions. In this sense, UMAA and<br />

MSU should be encouraged <strong>to</strong> evolve more <strong>to</strong>ward a “universitas”<br />

character, stressing their roles as sources <strong>of</strong> advanced<br />

knowledge and learning rather than focusing on providing<br />

general education (or socialization) at the undergraduate<br />

level.<br />

5. While it is natural <strong>to</strong> confine state policy <strong>to</strong> state<br />

boundaries, in reality such geopolitical boundaries are <strong>of</strong> no<br />

more relevance <strong>to</strong> public policy than they are <strong>to</strong> corporate<br />

strategies in an ever more integrated and interdependent<br />

global society. Hence Michigan’s strategies must broaden <strong>to</strong><br />

include regional, national, and global elements, including the<br />

possibility <strong>of</strong> encouraging the state’s two flagship research<br />

universities, the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Michigan and Michigan State<br />

<strong>University</strong>, <strong>to</strong> join <strong>to</strong>gether <strong>to</strong> form a true world university,<br />

capable <strong>of</strong> assisting the state <strong>to</strong> access global economic and<br />

human capital markets.<br />

6. Michigan’s research universities should explore new<br />

models for the transfer <strong>of</strong> knowledge from the campus in<strong>to</strong> the<br />

marketplace, including the utilization <strong>of</strong> endowment capital<br />

(perhaps with state match) <strong>to</strong> stimulate spin<strong>of</strong>f and startup<br />

activities and exploring entirely new approaches such as<br />

“open source – open content paradigms” in which the intellectual<br />

property created through research and instruction<br />

is placed in the public domain as a “knowledge commons,”<br />

available without restriction <strong>to</strong> all, in return for strong public<br />

support.<br />

7. Michigan should explore bold models aimed at producing<br />

the human capital necessary <strong>to</strong> compete economically<br />

with other regions (states, nations) and provide its<br />

citizens with prosperity and security. Lifelong learning will<br />

not only become a compelling need <strong>of</strong> citizens (who are only<br />

one paycheck away from the unemployment line in a knowledge-driven<br />

economy), but also a major responsibility <strong>of</strong> the<br />

state and its educational resources. One such model might<br />

be <strong>to</strong> develop a 21st-century analog <strong>to</strong> the G.I. Bill <strong>of</strong> the post<br />

WWII era that would provide–indeed, guarantee–all Michigan<br />

citizens with access <strong>to</strong> abundant, high-quality, diverse<br />

learning opportunities throughout their lives, and adapts <strong>to</strong><br />

their ever-changing needs<br />

8. Michigan should develop a leadership coalition–involving<br />

leaders from state government, industry, labor, education,<br />

and concerned citizens–with vision and courage sufficient <strong>to</strong><br />

challenge and break the stranglehold <strong>of</strong> the past on Michigan’s<br />

future!<br />

Although this roadmapping exercise was for a specific<br />

state, we believe it <strong>of</strong>fers a possible model <strong>of</strong> how<br />

regions can utilize the roadmapping process <strong>to</strong> develop<br />

their own unique paths <strong>to</strong> future prosperity, security,<br />

and social well-being for their citizens. We are currently<br />

engaged in further studies about how such regional<br />

technology roadmapping efforts can be applied<br />

<strong>to</strong> multiple-state regions or even nation-states. In an<br />

Epilogue section, we have suggested broadening this<br />

roadmapping activity <strong>to</strong> include the entire Great Lakes<br />

region, encompassing those states that once comprised<br />

the manufacturing center <strong>of</strong> the world. We suggest that

viii<br />

<strong>Roadmap</strong>ping for the Great Lakes states<br />

(Scott Swanm, CSCAR, 2003)<br />

these states could build on the unique capacity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

region’s flagship research universities <strong>to</strong> build strong<br />

regional advantage in a global, knowledge-driven<br />

economy. While such a regional plan would require<br />

considerable leadership at the level <strong>of</strong> both the state<br />

(governors) and higher education (university leaders),<br />

it could be the key <strong>to</strong> the economic future <strong>of</strong> the Great<br />

Lakes states.<br />

Finally, a word about the target audience for this<br />

study. The Michigan <strong>Roadmap</strong> is intended in part for<br />

leaders in the public sec<strong>to</strong>r (the Governor, Legislature,<br />

and other public <strong>of</strong>ficials), the business community<br />

(CEOs, labor leaders), higher education leaders, and<br />

the nonpr<strong>of</strong>it foundation sec<strong>to</strong>r. However, this report<br />

is also written for those interested, concerned citizens<br />

who have become frustrated with the deafening silence<br />

about Michigan’s future that characterizes our public,<br />

private, and education sec<strong>to</strong>rs. The state’s leaders, its<br />

government, industry, labor, and universities, have simply<br />

not been willing <strong>to</strong> acknowledge that the rest <strong>of</strong> the<br />

world is changing. They have held fast <strong>to</strong> an economic<br />

model that is not much different from the one that grew<br />

up around the heyday <strong>of</strong> the au<strong>to</strong>mobile era–an era that<br />

passed long ago.<br />

Michigan is far more at risk than many other states<br />

because its manufacturing-dominated culture is addicted<br />

<strong>to</strong> an entitlement mentality that has long since<br />

disappeared in other regions and industrial sec<strong>to</strong>rs.<br />

Moreover, politicians and the media are both irresponsible<br />

and myopic as they continue <strong>to</strong> fan the flames <strong>of</strong><br />

the voter hostility <strong>to</strong> an adequate tax base capable <strong>of</strong><br />

meeting both <strong>to</strong>day’s urgent social needs and longerterm<br />

investment imperatives such as education and<br />

innovation. As Bill Gates warned, cutting-edge companies<br />

no longer make decisions <strong>to</strong> locate and expand<br />

based on tax policies and incentives. Instead they base<br />

these decisions on a state’s talent pool and culture for<br />

innovation–priorities apparently no longer valued by<br />

many <strong>of</strong> Michigan’s leaders, at least when it comes <strong>to</strong><br />

tax policy.<br />

To be sure, it is difficult <strong>to</strong> address issues such as<br />

developing a tax system for a 21st-century economy,<br />

building world-class schools and colleges, or making<br />

the necessary investments for future generations in the<br />

face <strong>of</strong> the determination <strong>of</strong> the body politic still clinging<br />

tenaciously <strong>to</strong> past beliefs and practices. Yet the realities<br />

<strong>of</strong> a flat world will no longer <strong>to</strong>lerate procrastination<br />

or benign neglect. In Chapter 7 we have broadened<br />

the discussion <strong>to</strong> suggest several ideas for breaking this<br />

public policy logjam <strong>to</strong> facilitate the implementation <strong>of</strong><br />

the recommendations <strong>of</strong> the Michigan <strong>Roadmap</strong>.<br />

Finally, it should be acknowledged that much <strong>of</strong> the<br />

rhe<strong>to</strong>ric used in this report is intentionally provocative–if<br />

not occasionally incendiary. But recall here that<br />

old saying that sometimes the only way <strong>to</strong> get a mule<br />

<strong>to</strong> move is <strong>to</strong> whack it over the head with a 2x4 first <strong>to</strong><br />

get its attention. The Michigan <strong>Roadmap</strong> is intended as<br />

just such a 2x4 wake-up call <strong>to</strong> our state. For this effort<br />

<strong>to</strong> have value, we believe it essential <strong>to</strong> explore openly<br />

and honestly where our state is <strong>to</strong>day, where it must<br />

head for <strong>to</strong>morrow, and what actions will be necessary<br />

<strong>to</strong> get there. Michigan simply must s<strong>to</strong>p backing in<strong>to</strong><br />

the future and, instead, turn its attention <strong>to</strong> making the<br />

commitments and investments <strong>to</strong>day necessary <strong>to</strong> allow<br />

it <strong>to</strong> compete for prosperity and social well-being<br />

<strong>to</strong>morrow in a global, knowledge-driven economy.

ix<br />

Recommendations<br />

The Near Term<br />

The Longer Term<br />

Today’s Challenge: Enabling Michigan’s transition <strong>to</strong> a knowledgedriven<br />

economy capable <strong>of</strong> providing prosperity, security, and<br />

social well-being in a hypercompetitive global economy.<br />

Tomorrow’s Challenge: To provide all <strong>of</strong> Michigan’s citizens with the<br />

education and training they need, throughout their lives,<br />

whenever, wherever, and however they desire it,<br />

at high quality, and affordable cost.<br />

Key Vision:<br />

To invest more adequately, strategically, and intelligently.<br />

Key Vision: To develop a knowledge society<br />

capable <strong>of</strong> responding <strong>to</strong> the imperatives <strong>of</strong><br />

a 21st century, global, knowledge-driven society.<br />

Investment Goals:<br />

…human capital (lifelong learning)<br />

…new knowledge (research, innovation, entrepreneurism)<br />

…infrfastructure (institutions, labs, cyber)<br />

…policy (tax, investment, intellectual property)<br />

Goal: A society <strong>of</strong> learning, capable <strong>of</strong> adapting and evolving<br />

rapidly <strong>to</strong> provide learning opportunities, knowledge,<br />

and innovation during a period <strong>of</strong> extraordinary change.<br />

The Elements:<br />

The Elements:<br />

1. Increase participation <strong>of</strong> all citizens in higher education.<br />

2. Move Michigan in<strong>to</strong> <strong>to</strong>p quartile in higher ed investments.<br />

3. Targeted state investment in science and engineering.<br />

4. Stress alliances among Michigan’s colleges and universities.<br />

5. Michigan should increase investments in university research<br />

infrastructure (similar <strong>to</strong> Reseach Excellence Fund).<br />

6. Michigan universities should become more engaged in<br />

tech transfer and economic development.<br />

7. Michigan should develop incentives (including tax policy) <strong>to</strong><br />

stimulate private sec<strong>to</strong>r R&D and innovation.<br />

8. Public investment in infrastructure such as broadband is critical.<br />

9. Michigan should invest more in higher education marketplace<br />

(particularly need-based financial aid).<br />

10. State funds should be used <strong>to</strong> leverage private and federal funds.<br />

11. State universities should be provided with agility <strong>to</strong> adapt <strong>to</strong><br />

market, subject <strong>to</strong> accountability measures.<br />

1. Michigan must develop a more systemic and strategic approach<br />

<strong>to</strong> its knowledge resources.<br />

2. The state should encourage more diversity in institutions.<br />

3. New paradigms for K-16 education should be explored.<br />

4. UM and MSU should be encouraged <strong>to</strong> stress advanced education<br />

and research.<br />

5. UM and MSU should be encouraged <strong>to</strong> develop capacity <strong>to</strong><br />

access global markets.<br />

6. Michigan’s universities should explore bolder models <strong>of</strong> tech<br />

transfer, spin<strong>of</strong>fs, and startup activities.<br />

7. Michigan should consider bolder models for producing human<br />

capital such as a 21st century version <strong>of</strong> the G.I. Bill that<br />

guarantees lifelong educational opportunities for all<br />

citizens.

Contents<br />

Executive Summary<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

Chapter 1: Introduction<br />

Some Symp<strong>to</strong>ms <strong>of</strong> Our Plight<br />

Questions Concerning Michigan’s <strong>Future</strong><br />

Purpose <strong>of</strong> the Study<br />

Several Caveats<br />

Chapter 2: Setting the Context: An Environmental<br />

Scan<br />

Challenge One: The Knowledge Economy<br />

Challenge Two: Globalization<br />

Challenge Three: Demographics<br />

Challenge Four: Exponentiating Technologies<br />

The Implications<br />

Tomorrow’s Horizon<br />

Hakuna Matata<br />

Chapter 3: Michigan Today: A Knowledge Resource<br />

Map<br />

The Michigan Economy<br />

Educational Resources<br />

Human Capital<br />

Research and Development<br />

Other Assets<br />

The Writing on the Wall<br />

Chapter 4: Michigan Tomorrow: A Knowledge Society<br />

The Educational Needs <strong>of</strong> a 21st Century<br />

Citizen<br />

Building a Competitive Workforce<br />

The Importance <strong>of</strong> Technological Innovation<br />

The <strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> Public Higher Education<br />

A New Social Contract<br />

Over the Horizon<br />

A Vision for Michigan’s <strong>Future</strong>: A Knowledge<br />

Society<br />

Chapter 5: How Far Do We Have <strong>to</strong> Go The Gap<br />

Analysis<br />

Michigan’s Challenge: Economic<br />

Transformation<br />

Higher Education in Michigan: A Critical<br />

Asset at Great Risk<br />

Broader Human Capital Concerns<br />

The Production <strong>of</strong> New Knowledge: Research<br />

and Innovation<br />

Entrepreneurs, Startups, and High-Tech<br />

Economic Development<br />

Infrastructure<br />

Challenges at the Federal Level<br />

Public Policy<br />

Public Attitudes: Half Right (Essentially) and<br />

Half Wrong (Terribly!)<br />

Some Lessons from the Past<br />

Chapter 6: The Michigan <strong>Roadmap</strong><br />

The <strong>Roadmap</strong>: The Near Term (…Now!…)<br />

The <strong>Roadmap</strong>: The Longer Term (…But within<br />

a Decade…)<br />

One Final Recommendation: A Call for<br />

Leadership<br />

Chapter 7: A Broader Agenda<br />

Related Policy Areas<br />

Cultural Challenges<br />

A Final Observation<br />

Chapter 8: An Epilogue: Broadening the Vision <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Roadmap</strong>

xi<br />

Appendix A: A Comparison with the Cherry<br />

Commission Report<br />

Appendix B: The <strong>Millennium</strong> <strong>Project</strong><br />

[Appendix C: A <strong>Roadmap</strong> for the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Michigan]<br />

References

xii<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

As noted earlier, the roadmapping process utilizes<br />

a series <strong>of</strong> expert panels <strong>to</strong> define key issues, and then<br />

refines appropriate strategies through focus groups and<br />

sustained dialog. In the case <strong>of</strong> the Michigan <strong>Roadmap</strong>,<br />

a guidance group was formed that met frequently <strong>to</strong><br />

guide and shape the process and recommendations<br />

over the three-year period <strong>of</strong> the study. This group included<br />

Marvin Peterson, Dan Atkins, Kathy Willis, Carl<br />

Berger, Bruce Montgomery, Maurita Holland, and was<br />

ably assisted by graduate students Dana Walker and<br />

Laurel Park.<br />

During this period numerous other experts participated<br />

in the process, including Michael Boulus, Doug<br />

Van Houweling, Doug Ross, Craig Ruff, Paul Dimond,<br />

John Austin, Lou Glazer, Donald Grimes, Dan Hurley,<br />

Elizabeth Gerber, and Philip Power. In addition, there<br />

was extensive interaction with the leadership, faculty,<br />

and staff <strong>of</strong> both public and independent colleges and<br />

universities in Michigan.<br />

More broadly, this effort was coordinated with several<br />

other ongoing projects at the national level, including<br />

major projects <strong>of</strong> the National Academies chaired by<br />

the direc<strong>to</strong>r <strong>of</strong> the Michigan <strong>Roadmap</strong> (JJD): the IT Forum<br />

studying the impact <strong>of</strong> information technology on<br />

the future <strong>of</strong> the research university, the Federal Science<br />

and Technology guidance group <strong>of</strong> the Committee on<br />

Science, Engineering, and Public Policy <strong>of</strong> the National<br />

Academies, and the Commission <strong>to</strong> Assess the Capacity<br />

<strong>of</strong> United States Engineering Research. Similarly,<br />

other projects involving the direc<strong>to</strong>r also had influence<br />

on the <strong>Roadmap</strong>: the Strategic Planning Committee <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> California, the Task Force <strong>to</strong> Develop<br />

a Higher Education <strong>Future</strong> for Kansas City, and participation<br />

with state and university groups in various regions<br />

(Texas, Colorado, Ohio, North Carolina, Arizona,<br />

Ontario, British Columbia). In addition, the direc<strong>to</strong>r’s<br />

involvement during this period in several international<br />

groups also informed the study (OECD, the Glion Colloquium).<br />

The direc<strong>to</strong>r <strong>of</strong> the Michigan <strong>Roadmap</strong> project wishes<br />

<strong>to</strong> acknowledge the contributions <strong>of</strong> these individuals<br />

and related studies. However it is also important <strong>to</strong><br />

stress that this report, including its recommendations,<br />

while very much influenced by these groups, was authored<br />

by the direc<strong>to</strong>r, who accepts full responsibility<br />

for its language and conclusions–particularly the more<br />

provocative language and controversial recommendations.<br />

Finally, it is important <strong>to</strong> state at the outset that<br />

this study was supported by an independent nonpr<strong>of</strong>it<br />

foundation, the Atlantic Philanthropies, which has long<br />

been one <strong>of</strong> the most generous and effective patrons <strong>of</strong><br />

higher-education research. We are deeply grateful for<br />

their support, encouragement, and guidance. We are<br />

also grateful for the independence enabled by their support<br />

that has allowed us <strong>to</strong> approach this project with<br />

a level <strong>of</strong> creativity and candor unusual in the publicpolicy<br />

arena.<br />

JJD<br />

Ann Arbor<br />

September, 2005

Chapter 1<br />

Introduction<br />

“It is not the strongest <strong>of</strong> the species that survive,<br />

nor the most intelligent, but rather the ones<br />

most responsive <strong>to</strong> change.” – Charles Darwin<br />

So what’s the problem Why is there a need for yet<br />

another study <strong>of</strong> the future <strong>of</strong> the state <strong>of</strong> Michigan<br />

The reason is simple: Michigan’s old fac<strong>to</strong>ry-based<br />

manufacturing economy is dying, slowly but surely,<br />

putting at risk the welfare <strong>of</strong> millions <strong>of</strong> citizens in<br />

our state, in the face <strong>of</strong> withering competition from an<br />

emerging global economy driven by knowledge and innovation.<br />

From California <strong>to</strong> North Carolina, Dublin <strong>to</strong><br />

Bangalore, other regions, states, and nations are shifting<br />

their public policies and investments <strong>to</strong> support the new<br />

imperatives <strong>of</strong> a knowledge economy such as knowledge<br />

creation (research, innovation, entrepreneurial activities),<br />

human capital (lifelong learning and advanced<br />

education, particularly in science and engineering), and<br />

infrastructure (colleges and universities, research labora<strong>to</strong>ries,<br />

broadband networks). As Thomas Friedman<br />

puts it, “The world is flat! Globalization has collapsed<br />

time and distance and raised the notion that someone<br />

anywhere on earth can do your job, more cheaply. Can<br />

we rise <strong>to</strong> the challenge on this leveled playing field”<br />

(Friedman, 2005).<br />

Yet in Michigan there is a deafening silence about<br />

the implications <strong>of</strong> a global, knowledge-driven global<br />

economy for our state’s future. There is little evidence<br />

<strong>of</strong> effective policies, new investments, or visionary<br />

leadership capable <strong>of</strong> reversing the downward spiral<br />

<strong>of</strong> Michigan’s economy. For whatever reason, leaders<br />

in the state’s public and private sec<strong>to</strong>rs continue <strong>to</strong><br />

cling tenaciously <strong>to</strong> past beliefs and practices, preoccupied<br />

with obsolete and largely irrelevant issues (e.g.,<br />

the culture wars, entitlements, tax cuts or abatements,<br />

and gimmicks such as lotteries and casinos) rather than<br />

developing strategies, taking actions, and making the<br />

necessary investments <strong>to</strong> achieve economic prosperity<br />

and social well-being in the new global economic order.<br />

Preoccupied with obsolete political battles, addicted <strong>to</strong><br />

entitlements, and assuming that what worked before<br />

will work again, Michigan <strong>to</strong>day is sailing blindly in<strong>to</strong><br />

a pr<strong>of</strong>oundly different future.<br />

For many years now we have seen our low-skill,<br />

high-pay fac<strong>to</strong>ry jobs downsized by increasing productivity,<br />

shifted <strong>to</strong> lower cost states, or outsourced <strong>to</strong> lowwage<br />

countries. We have fallen behind the rest <strong>of</strong> the<br />

nation in adding high value-added service firms and<br />

jobs during the transition <strong>to</strong> a knowledge economy. According<br />

<strong>to</strong> a recent study at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Michigan,<br />

our state lost 254,000 jobs from 2000 <strong>to</strong> 2003, a 22% decline,<br />

including 163,000 manufacturing jobs. (Glazer,<br />

2005). In 2004, Michigan had the worst performing state<br />

economy in the nation, ranking as the only state that<br />

has lost more jobs than it created, according <strong>to</strong> the Joint<br />

Economic Committee <strong>of</strong> Congress. Detroit has recently<br />

become the nation’s poorest city, with over one-third <strong>of</strong><br />

its residents living below the federal poverty level (U.S.<br />

Census Bureau, 2005). Yet if we look about, we see other<br />

states, not <strong>to</strong> mention other nations, investing heavily<br />

and restructuring their economies <strong>to</strong> create high-skill,<br />

high-wage jobs in areas such as information services,<br />

financial services, trade, and pr<strong>of</strong>essional and technical<br />

services.<br />

For decades the leadership <strong>of</strong> this state–whether in<br />

state government, corporations, labor, cities, or colleges<br />

and universities–has been backing in<strong>to</strong> the future, hoping<br />

in vain that our fac<strong>to</strong>ry-based manufacturing economy<br />

would return. Yet that manufacturing economy,<br />

so dominant in a 20th-century world, has not returned,

and the risk <strong>of</strong> <strong>to</strong>day’s myopia is that by the time we<br />

have come <strong>to</strong> realize the permanence <strong>of</strong> this economic<br />

transformation, the out-sourcing and <strong>of</strong>f-shoring train<br />

will have left the station, taking with it the rest <strong>of</strong> our<br />

good jobs.<br />

Perhaps nowhere is this inability <strong>to</strong> read the writing<br />

on the wall more apparent that in our state’s approach<br />

<strong>to</strong> the development <strong>of</strong> the human resources and new<br />

knowledge necessary <strong>to</strong> compete in a global, knowledge-driven<br />

economy. Michigan’s strategies and policies<br />

with respect <strong>to</strong> advanced learning and knowledge<br />

production have been woefully inadequate, all <strong>to</strong>o <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

political in character, and largely reflecting a state<br />

<strong>of</strong> denial about the imperatives <strong>of</strong> the emerging global<br />

economy.<br />

Some Symp<strong>to</strong>ms <strong>of</strong> Our Plight<br />

During the last half <strong>of</strong> the 20th century, Michigan<br />

saw many <strong>of</strong> its low-skill, high-wage manufacturing<br />

jobs downsized as companies restructured <strong>to</strong> increase<br />

productivity and outsourced <strong>to</strong> lower wage states and<br />

nations <strong>to</strong> reduce costs. Today our state is beginning<br />

<strong>to</strong> experience the same phenomenon with higher-skill<br />

service jobs through <strong>of</strong>f-shoring <strong>to</strong> emerging economies<br />

such as India, China, and the Eastern Bloc nations.<br />

While labor cost is certainly a fac<strong>to</strong>r, more important<br />

has been the determination <strong>of</strong> these regions <strong>to</strong> invest<br />

heavily in educating a highly skilled, high-quality<br />

workforce in key economic sec<strong>to</strong>rs. This has happened<br />

during a period when Michigan has been largely asleep<br />

at the wheel, assuming our low-skill workforce would<br />

remain competitive and our fac<strong>to</strong>ry-based manufacturing<br />

economy would prosper indefinitely.<br />

It may seem surprising that a state, which a century<br />

and a half ago led the nation in its commitment <strong>to</strong> building<br />

a great public education system aimed at serving<br />

all <strong>of</strong> its citizens, would be failing <strong>to</strong>day in its human<br />

resource development. Perhaps it is ironic that a state<br />

with seemingly infinite resources <strong>of</strong> fur, timber, iron,<br />

and copper—a state with boundless confidence in the<br />

future—should have played such a leadership role in<br />

developing the models <strong>of</strong> higher education that would<br />

later serve all <strong>of</strong> America. The <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Michigan,<br />

while not the first <strong>of</strong> the state universities, is nevertheless<br />

commonly regarded as the “mother <strong>of</strong> public universities”<br />

(Kerr, 1963), responsible for and responsive <strong>to</strong><br />

the needs <strong>of</strong> the people who founded it and supported<br />

it, even as it sought <strong>to</strong> achieve quality equal <strong>to</strong> that <strong>of</strong> the<br />

most distinguished private institutions. Michigan State<br />

<strong>University</strong> is also regarded as a national leader, the pro<strong>to</strong>type<br />

<strong>of</strong> the great land-grant universities. And Wayne<br />

State <strong>University</strong> has provided an important model <strong>of</strong><br />

the urban university, serving the needs <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> our<br />

nation’s great cities. When these universities were augmented<br />

by the evolution <strong>of</strong> Michigan’s comprehensive<br />

and regional universities, community colleges, and independent<br />

colleges, the state gained a justified reputation<br />

for one <strong>of</strong> the nation’s most forward-looking and<br />

outstanding higher education systems.<br />

What is significant is that the strength <strong>of</strong> Michigan–<br />

its capacity <strong>to</strong> build and sustain such extraordinary institutions–arose<br />

from our state’s ability <strong>to</strong> look <strong>to</strong> the<br />

future, its willingness <strong>to</strong> take the actions and make the<br />

investments that would yield prosperity and well-being<br />

for future generations. Yet <strong>to</strong>day this spirit <strong>of</strong> public<br />

investment for the future has disappeared. Decades <strong>of</strong><br />

failed public policies and inadequate investment now<br />

threaten the extraordinary educational resources built<br />

through the vision and sacrifices <strong>of</strong> past generations. In<br />

our times, state government has come <strong>to</strong> view public<br />

higher education as low priority and expendable during<br />

hard times in preference <strong>to</strong> funding other social priorities<br />

such as prisons and politically popular tax relief.<br />

All <strong>to</strong>o frequently the annual appropriation process is<br />

approached more as a political football game rather than<br />

as an opportunity for strategic investment in the future.<br />

It has become painfully evident that our current policies<br />

<strong>of</strong> inadequate state support for higher education<br />

is destroying Michigan’s long-standing commitment <strong>to</strong><br />

providing “an uncommon education for the common<br />

man,” in the words <strong>of</strong> James Angell, one <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> Michigan’s early presidents (Peckham, 1967).<br />

Beyond educational opportunities, there is another<br />

key <strong>to</strong> economic prosperity: technological innovation.<br />

As the source <strong>of</strong> new products and services, innovation<br />

is directly responsible for the most dynamic areas <strong>of</strong> the<br />

U.S. economy. It has become even more critical <strong>to</strong> our<br />

prosperity and security in <strong>to</strong>day’s hypercompetitive,<br />

global, knowledge-driven economy. Our American culture–based<br />

on a highly diverse population, democratic<br />

values, and free-market practices–provides an unusu-

ally fertile environment for technological innovation.<br />

However, his<strong>to</strong>ry has also shown that significant public<br />

investment is necessary <strong>to</strong> produce the essential ingredients<br />

for innovation <strong>to</strong> flourish: new knowledge (research),<br />

human capital (education), infrastructure (facilities,<br />

labora<strong>to</strong>ries, communications networks), and<br />

policies (tax, intellectual property).<br />

Again, the irony <strong>of</strong> our state’s plight <strong>to</strong>day is that<br />

Michigan led the world in technological innovation<br />

throughout much <strong>of</strong> the 20th century. The au<strong>to</strong>mobile<br />

industry concentrated in Michigan because <strong>of</strong> the skills<br />

<strong>of</strong> our craftsmen, engineers, technologists, and technicians<br />

and the management and financial skills <strong>of</strong> corporate<br />

leadership as the industry grew <strong>to</strong> global proportions.<br />

Michigan became the arsenal <strong>of</strong> democracy during<br />

World War II. While the workforce skills required<br />

by fac<strong>to</strong>ry manufacturing required only minimal formal<br />

education, technological excellence and skillful<br />

management enabled Michigan corporations <strong>to</strong> achieve<br />

global impact. Basic research was also key, funded by<br />

industry in world-class labora<strong>to</strong>ries such as the Ford<br />

Scientific Labora<strong>to</strong>ry and the General Mo<strong>to</strong>rs Research<br />

Labora<strong>to</strong>ry. Michigan also benefited greatly from the<br />

presence <strong>of</strong> two world-class research universities, the<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Michigan and Michigan State <strong>University</strong>.<br />

However, by the late 20th century, shareholders began<br />

demanding short-term strategies <strong>to</strong> increase quarterly<br />

earnings rather than longer-term investments in<br />

technology key <strong>to</strong> the future <strong>of</strong> industry. To be sure,<br />

cost-cutting, <strong>to</strong>tal quality management, lean manufacturing,<br />

and just-in-time supply chains were able <strong>to</strong> enhance<br />

productivity during the 1980s and early 1990s,<br />

albeit at the expense <strong>of</strong> hundreds <strong>of</strong> thousands <strong>of</strong> manufacturing<br />

jobs as companies restructured their workforces.<br />

Unfortunately, such restructuring also eliminated<br />

much <strong>of</strong> the corporate R&D function, constraining<br />

industry increasingly <strong>to</strong> technological progress at the<br />

margin rather than based on breakthrough technologies<br />

and innovations. This was compounded by management’s<br />

increasing focus on near-term pr<strong>of</strong>its, even<br />

at the expense <strong>of</strong> longer-term market share. Michigan’s<br />

Washing<strong>to</strong>n influence was used more <strong>to</strong> block federal<br />

regulation in areas such as emissions standards and<br />

fuel economy than attracting additional federal R&D<br />

dollars <strong>to</strong> the state, thereby ignoring the growing concerns<br />

about issues such as petroleum imports and global<br />

climate change, which would threaten the very viability<br />

<strong>of</strong> Michigan industry by 2000. As a consequence,<br />

at a time when other states and nations were investing<br />

heavily in stimulating the technological innovation <strong>to</strong><br />

secure future economic prosperity, Michigan was missing<br />

in action, significantly under-investing in the seeds<br />

<strong>of</strong> innovation.<br />

What is really at stake <strong>to</strong>day is building Michigan’s<br />

regional advantage, allowing it <strong>to</strong> compete for prosperity<br />

and quality <strong>of</strong> life, in an increasingly competitive<br />

global economy. In a knowledge-intensive society,<br />

regional advantage is not achieved through traditional<br />

political devices such as tax cuts for the wealthy, regula<strong>to</strong>ry<br />

relief <strong>of</strong> polluters, entitlements for those without<br />

need, or tax-subsidized gimmicks such as lotteries,<br />

casinos, or sports stadiums. A knowledge-based,<br />

competitive economy is achieved through creating a<br />

highly educated and skilled workforce. It requires an<br />

environment that stimulates creativity, innovation, and<br />

entrepreneurial behavior. It requires public investment<br />

in the ingredients <strong>of</strong> innovation–educated people and<br />

new knowledge–and the infrastructure <strong>to</strong> support advanced<br />

learning, research, and innovation. Put another<br />

way, it requires strong public purpose, wise public policy,<br />

and adequate investment <strong>to</strong> create a true knowledge<br />

society.<br />

Questions Concerning Michigan’s <strong>Future</strong><br />

Creating a different economic engine that will be<br />

competitive in a knowledge-based, global economy<br />

also demands vision and leadership. It requires all <strong>of</strong> us<br />

<strong>to</strong> think about our future and where Michigan might fit<br />

in<strong>to</strong> that future. To illustrate, consider several provocative<br />

questions concerning Michigan’s future:<br />

1. What will the economic engine for our state be<br />

20 years from <strong>to</strong>day Does anybody know Is anybody<br />

thinking about this It certainly won’t be manufacturing,<br />

at least that based on low-skill fac<strong>to</strong>ry jobs. If this<br />

economic engine is the service sec<strong>to</strong>r <strong>of</strong> our economy,<br />

will these be high-skill, high-wage, knowledge-driven<br />

activities Or will we be flipping burgers and mowing<br />

each other’s lawns, while the most rewarding jobs have<br />

all flown <strong>of</strong>f (rather, zipped <strong>of</strong>f over the Internet) <strong>to</strong> other<br />

states, regions, and nations

2. Although it may be blasphemy <strong>to</strong> suggest it, suppose<br />

the price <strong>of</strong> gasoline in the United States should<br />

move up <strong>to</strong> its actual cost without artificial subsidies<br />

(currently about $5.00 per gallon in North America). Or<br />

suppose, even more boldly, that within the next two decades<br />

we pass over M. King Hubbert’s peak in global oil<br />

production (and a decade or so later do the same with<br />

natural gas), as an increasing number <strong>of</strong> geologists are<br />

now predicting (Hirsch, 2005). Do we honestly believe<br />

that Detroit’s au<strong>to</strong>mobile industry could survive a future<br />

where fossil fuels have either disappeared or have<br />

become <strong>to</strong>o expensive <strong>to</strong> use in transportation And if<br />

you still have confidence in that industry’s technological<br />

ingenuity <strong>to</strong> come up with alternatives such as hydrogen-based<br />

fuels or electric vehicles (although with no<br />

fossil fuels, this would imply a massive commitment <strong>to</strong><br />

nuclear power), then suppose further that information<br />

and communications technologies continue <strong>to</strong> evolve<br />

at the pace <strong>of</strong> Moore’s Law, a thousand-fold within a<br />

decade, a million-fold within two decades, and so on.<br />

What is the role <strong>of</strong> transportation in a world in which<br />

we can faithfully replicate any aspect <strong>of</strong> human interaction–sight,<br />

sound, <strong>to</strong>uch, taste, smell–with perfect fidelity<br />

at a distance (the “stim-sim” experience suggested<br />

by science fiction writers) (Gibson, 1983)<br />

3. As Michigan’s population ages, what will our<br />

workforce look like We already have seen the out-migration<br />

<strong>of</strong> young adults in the 25-44 age range, leaving<br />

behind an aging baby-boomer population demanding<br />

priorities such as expensive health care, even more prisons,<br />

homeland security, and reduced tax burdens, <strong>to</strong><br />

the neglect <strong>of</strong> education–and the future (Kris<strong>to</strong>f, 2005).<br />

Suppose human life span were <strong>to</strong> double during the<br />

21st century, as it did during the 20th century (from 40<br />