Karst geohazards in the UK: the use of digital data for hazard ... - Ispra

Karst geohazards in the UK: the use of digital data for hazard ... - Ispra

Karst geohazards in the UK: the use of digital data for hazard ... - Ispra

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Karst</strong> <strong>geo<strong>hazard</strong>s</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>UK</strong>: <strong>the</strong> <strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>digital</strong> <strong>data</strong> <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>hazard</strong> management<br />

A.R. Farrant & A.H. Cooper<br />

British Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nott<strong>in</strong>gham NG12 5GG, <strong>UK</strong> (e-mail: arf@bgs.ac.uk)<br />

An essential prerequisite <strong>for</strong> any eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g or<br />

hydrogeological <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>of</strong> soluble rocks<br />

is <strong>the</strong> identification and description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

characteristic, observable and detectable dissolution<br />

features, such as stream s<strong>in</strong>ks, spr<strong>in</strong>gs, s<strong>in</strong>kholes<br />

and caves. The British Geological Survey (BGS) is<br />

creat<strong>in</strong>g a National <strong>Karst</strong> Database (NKD) that records<br />

such features across <strong>the</strong> country. The <strong>data</strong>base currently<br />

covers much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> region underla<strong>in</strong> by Carboniferous<br />

Limestone, <strong>the</strong> Chalk, and particularly <strong>the</strong> Permo-Triassic<br />

gypsum and halite where rapid, active dissolution has<br />

ca<strong>use</strong>d significant subsidence and build<strong>in</strong>g damage. In<br />

addition to, and separate from, <strong>the</strong> identification <strong>of</strong><br />

specific karst features, <strong>the</strong> BGS has created a National<br />

<strong>Karst</strong> Geo<strong>hazard</strong> geographical <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation system (GIS).<br />

This has been created to identify areas that may potentially<br />

conta<strong>in</strong> karst <strong>geo<strong>hazard</strong>s</strong>. Initially, all <strong>the</strong> soluble<br />

rock units identified from <strong>the</strong> BGS 1:50 000 scale <strong>digital</strong><br />

geological map are extracted. Each soluble unit has been<br />

given an objective score, <strong>in</strong>terpreted, as based on factors<br />

<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g lithology, topography, geomorphological position<br />

and characteristic superficial cover deposits. This<br />

national zonation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se soluble rocks can <strong>the</strong>n be <strong>use</strong>d<br />

to identify areas where <strong>the</strong> occurrence potential <strong>for</strong><br />

karstic features is significant, and where dissolution features<br />

might affect <strong>the</strong> stability <strong>of</strong> build<strong>in</strong>gs and <strong>in</strong>frastructure,<br />

or where karstic groundwater flow might occur. Both<br />

<strong>data</strong>sets are seen as <strong>in</strong>valuable scientific tools that have<br />

already been widely <strong>use</strong>d to support site <strong>in</strong>vestigation,<br />

groundwater <strong>in</strong>vestigations, plann<strong>in</strong>g, construction and<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>surance underwrit<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>esses.<br />

travel, commonly some distance from <strong>the</strong>ir source, thus<br />

pos<strong>in</strong>g ano<strong>the</strong>r <strong>for</strong>m <strong>of</strong> unanticipated environmental<br />

risk.<br />

Databases and maps <strong>of</strong> karst <strong>hazard</strong>s are important<br />

<strong>for</strong> understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> severity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> problem, and <strong>the</strong>y<br />

constitute <strong>use</strong>ful tools <strong>for</strong> public governance choices <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>hazard</strong> avoidance that have relevance to plann<strong>in</strong>g, eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

development and <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>surance underwrit<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>dustry. Developers, planners and local government<br />

can be expected to operate effectively only if <strong>the</strong>y<br />

have advance scientific warn<strong>in</strong>g about <strong>the</strong> <strong>hazard</strong>s that<br />

might be present and have access to relevant geological<br />

<strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation.<br />

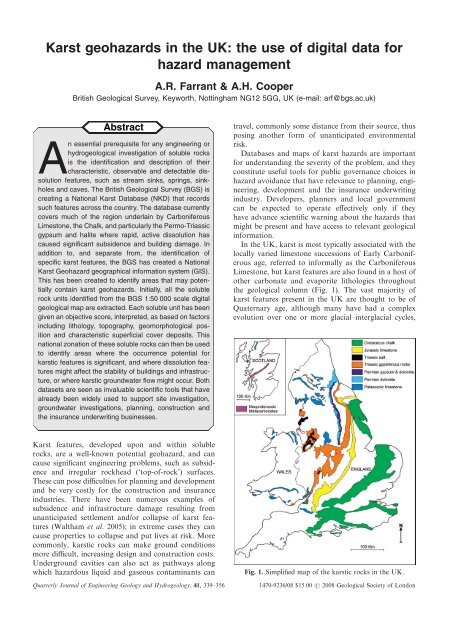

In <strong>the</strong> <strong>UK</strong>, karst is most typically associated with <strong>the</strong><br />

locally varied limestone successions <strong>of</strong> Early Carboniferous<br />

age, referred to <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mally as <strong>the</strong> Carboniferous<br />

Limestone, but karst features are also found <strong>in</strong> a host <strong>of</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r carbonate and evaporite lithologies throughout<br />

<strong>the</strong> geological column (Fig. 1). The vast majority <strong>of</strong><br />

karst features present <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>UK</strong> are thought to be <strong>of</strong><br />

Quaternary age, although many have had a complex<br />

evolution over one or more glacial–<strong>in</strong>terglacial cycles,<br />

<strong>Karst</strong> features, developed upon and with<strong>in</strong> soluble<br />

rocks, are a well-known potential geo<strong>hazard</strong>, and can<br />

ca<strong>use</strong> significant eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g problems, such as subsidence<br />

and irregular rockhead (‘top-<strong>of</strong>-rock’) surfaces.<br />

These can pose difficulties <strong>for</strong> plann<strong>in</strong>g and development<br />

and be very costly <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> construction and <strong>in</strong>surance<br />

<strong>in</strong>dustries. There have been numerous examples <strong>of</strong><br />

subsidence and <strong>in</strong>frastructure damage result<strong>in</strong>g from<br />

unanticipated settlement and/or collapse <strong>of</strong> karst features<br />

(Waltham et al. 2005); <strong>in</strong> extreme cases <strong>the</strong>y can<br />

ca<strong>use</strong> properties to collapse and put lives at risk. More<br />

commonly, karstic rocks can make ground conditions<br />

more difficult, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g design and construction costs.<br />

Underground cavities can also act as pathways along<br />

which <strong>hazard</strong>ous liquid and gaseous contam<strong>in</strong>ants can<br />

Quarterly Journal <strong>of</strong> Eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g Geology and Hydrogeology, 41, 339–356<br />

Fig. 1. Simplified map <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> karstic rocks <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>UK</strong>.<br />

1470-9236/08 $15.00 2008 Geological Society <strong>of</strong> London

340<br />

A.R. FARRANT & A.H. COOPER<br />

and some caves are potentially much older. Triassic<br />

palaeokarst is present <strong>in</strong> some areas (Simms 1990), but is<br />

generally <strong>of</strong> local extent. An overview <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>UK</strong> karst<br />

has been given by Waltham et al. (1997).<br />

Palaeozoic and Neoproterozoic limestones<br />

The oldest rocks that exhibit karstic features <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>UK</strong><br />

are <strong>the</strong> th<strong>in</strong> metacarbonate beds preserved with<strong>in</strong> parts<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Dalradian Supergroup <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Scottish Highlands.<br />

The features here are perhaps analogous to <strong>the</strong><br />

Scand<strong>in</strong>avian stripe karst (Lauritzen 2001). Numerous<br />

small caves, s<strong>in</strong>kholes, stream s<strong>in</strong>ks and spr<strong>in</strong>gs have<br />

been recorded <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> App<strong>in</strong> and Schiehallion regions <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Scottish Highlands (Oldham 1975). However, many<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se are <strong>in</strong> remote upland areas and generally pose<br />

little risk to <strong>in</strong>frastructure. Elsewhere <strong>in</strong> NW Scotland,<br />

Cambrian to Ordovician limestones and dolomites<br />

belong<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> Durness Group crop out <strong>in</strong> a long<br />

narrow belt along <strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mo<strong>in</strong>e Thrust and on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Isle <strong>of</strong> Skye. Several extensive well-developed karstic<br />

cave systems, <strong>for</strong> example <strong>the</strong> Allt nan Uamh system,<br />

and those <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Traligill valley have been described (e.g.<br />

Lawson 1988; Waltham et al. 1997), although aga<strong>in</strong><br />

many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se are <strong>in</strong> remote upland areas.<br />

Far<strong>the</strong>r south, m<strong>in</strong>or dissolution features and<br />

enlarged fractures have been identified from limestones<br />

<strong>of</strong> Wenlock (Silurian) age <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> West Midlands and <strong>the</strong><br />

Welsh Borders, but no significant cave systems are yet<br />

known. Limestones <strong>of</strong> Devonian age crop out <strong>in</strong> parts <strong>of</strong><br />

Devon, particularly around Plymouth, Buckfastleigh<br />

and Torbay. Several well-developed cave systems are<br />

known <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se areas (Oldham et al. 1986), along with<br />

stream s<strong>in</strong>ks, ‘los<strong>in</strong>g’ streams, karstic spr<strong>in</strong>gs, s<strong>in</strong>kholes<br />

(dol<strong>in</strong>es) and areas <strong>of</strong> irregular rockhead. Infrastructure<br />

problems with karstic cavities and buried s<strong>in</strong>kholes have<br />

been reported <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Plymouth area.<br />

It is <strong>the</strong> Carboniferous Limestone that hosts <strong>the</strong><br />

best-developed karst landscapes and <strong>the</strong> longest and<br />

most-developed cave systems <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> country. It occurs<br />

widely throughout western and nor<strong>the</strong>rn England and <strong>in</strong><br />

Wales, and karst features are present on and with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> outcrop (Waltham et al. 1997). Particularly<br />

well-developed karst occurs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Mendip Hills,<br />

around <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn crop <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> South Wales coalfield<br />

(Ford 1989), <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Derbyshire Peak District and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Yorkshire Dales and adjacent areas, runn<strong>in</strong>g up <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong><br />

nor<strong>the</strong>rn Penn<strong>in</strong>es. Less well-known karst areas <strong>in</strong>clude<br />

<strong>the</strong> Forest <strong>of</strong> Dean, <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn crop <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> South<br />

Wales coalfield from Glamorgan through <strong>the</strong> Gower to<br />

Pembrokeshire, <strong>in</strong> North Wales around <strong>the</strong> Vale <strong>of</strong><br />

Clwyd, and around <strong>the</strong> fr<strong>in</strong>ges <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Lake District. In<br />

all <strong>the</strong>se areas, well-developed karstic dra<strong>in</strong>age systems,<br />

s<strong>in</strong>kholes and extensive cave systems are common,<br />

many <strong>of</strong> which are associated with significant allogenic<br />

dra<strong>in</strong>age catchments as a source <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dissolution<br />

waters.<br />

Fig. 2. A s<strong>in</strong>khole <strong>for</strong>med after severe flood<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> 1968 near<br />

Cheddar, Somerset [ST 4765 5620]. Superficial loessic cover<br />

sands have slumped <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> underly<strong>in</strong>g GB Cavern. An<br />

attempt was made to fill <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> hole with old cars, which can<br />

still be seen <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> cave below. Photo A. Farrant, copyright<br />

NERC.<br />

The major challenges associated with <strong>the</strong>se karst areas<br />

are water supply protection (both quality and quantity),<br />

geological conservation and practical eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g problems<br />

related to mitigat<strong>in</strong>g and accommodat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

result<strong>in</strong>g subsurface voids. Subsidence associated with<br />

s<strong>in</strong>khole <strong>for</strong>mation is commonly encountered <strong>in</strong> remote<br />

and rural areas with little impact on property and<br />

<strong>in</strong>frastructure, but damage to ho<strong>use</strong>s, tracks and roads is<br />

locally a problem. Commonly <strong>of</strong> greater significance,<br />

many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se subsidence hollows are sites <strong>for</strong> illegal<br />

tipp<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> farm and o<strong>the</strong>r ref<strong>use</strong> or waste, which can<br />

ca<strong>use</strong> rapid contam<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> groundwater and local<br />

dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g supplies (Fig. 2).<br />

Permian dolomites and limestones<br />

The Permian carbonates <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>UK</strong> are dom<strong>in</strong>ated by<br />

magnesium-rich limestones and dolomites. The solubility<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se rocks is characteristically lower than that<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pure limestones, and so karstic features are less<br />

well developed <strong>in</strong> this terra<strong>in</strong>. However, <strong>the</strong> dolomites<br />

are closely associated with bodies <strong>of</strong> gypsum, which<br />

typically are heavily karstified. Numerous small (generally<br />

less than a few tens <strong>of</strong> metres <strong>in</strong> length) cave systems<br />

are present along <strong>the</strong> outcrop <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> magnesian limestones<br />

from near Mansfield <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> south to Sunderland<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> north. Some s<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g streams are present as are<br />

numerous spr<strong>in</strong>gs, but very few s<strong>in</strong>kholes are to be<br />

found (possibly beca<strong>use</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>fill<strong>in</strong>g by agricultural practices<br />

over <strong>the</strong> centuries) and <strong>the</strong> rock is generally not<br />

problematical <strong>for</strong> eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g purposes. However,<br />

numerous open jo<strong>in</strong>ts, <strong>in</strong>cipient conduit systems on bedd<strong>in</strong>g<br />

planes, palaeokarst, and sediment-<strong>in</strong>filled fissures<br />

can be identified <strong>in</strong> road cutt<strong>in</strong>gs and quarries. Hydrogeologically,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se rocks support a m<strong>in</strong>or to moderatesized<br />

aquifer, potentially susceptible to resource damage<br />

from pollution and land development, especially from<br />

landfill contam<strong>in</strong>ation from <strong>for</strong>mer <strong>in</strong>filled quarries.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> Mendips, South Wales and parts <strong>of</strong><br />

Devon, limestone-rich Permo-Triassic conglomerates

KARST GEOHAZARDS IN THE <strong>UK</strong> 341<br />

(predom<strong>in</strong>antly, but not exclusively derived from<br />

Carboniferous limestone uplands) can be expected to<br />

host karstic cave systems, perhaps <strong>the</strong> most famous<br />

example be<strong>in</strong>g Wookey Hole <strong>in</strong> Somerset.<br />

Jurassic limestones<br />

Jurassic limestones extend across much <strong>of</strong> central,<br />

sou<strong>the</strong>rn and eastern England <strong>in</strong> a belt from Dorset to<br />

North Yorkshire, and <strong>in</strong> parts <strong>of</strong> western Scotland.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> karst <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se rocks is not as well developed<br />

as <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> more massive Palaeozoic limestone<br />

terra<strong>in</strong>, karst features do occur, particularly <strong>in</strong> some <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Portlandian and Purbeck limestones <strong>in</strong> Dorset and<br />

Wiltshire, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cornbrash, and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Corallian limestones<br />

around Ox<strong>for</strong>d and on <strong>the</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn flank <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

North York Moors, where a cave system >1 km long<br />

has recently been discovered. <strong>Karst</strong> is also well developed<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> L<strong>in</strong>colnshire Limestone south <strong>of</strong> Grantham<br />

(H<strong>in</strong>dley 1965). Here, water supply protection is <strong>the</strong><br />

ma<strong>in</strong> issue, although localized subsidence and areas <strong>of</strong><br />

irregular rock-head are to be expected.<br />

Cretaceous Chalk<br />

The Chalk is <strong>the</strong> most widespread carbonate rock <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

country and <strong>of</strong> immense importance <strong>for</strong> its water supply<br />

resource. It <strong>for</strong>ms <strong>the</strong> <strong>UK</strong>’s most important aquifer.<br />

<strong>Karst</strong> features occur <strong>in</strong> many parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chalk outcrop,<br />

particularly along <strong>the</strong> marg<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Palaeogene<br />

cover (Farrant 2001). In <strong>the</strong>se areas, <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong><br />

dissolutionally enlarged fissures and conduits can potentially<br />

ca<strong>use</strong> problems <strong>for</strong> groundwater supply by creat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

rapid-transport contam<strong>in</strong>ant pathways though <strong>the</strong><br />

aquifer (Maurice et al. 2006). This is particularly important<br />

as parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chalk outcrop underlie major transport<br />

corridors and urban areas; both <strong>of</strong> which are<br />

notorious suppliers <strong>of</strong> surface-ga<strong>the</strong>red contam<strong>in</strong>ants<br />

via run<strong>of</strong>f. Chalk dissolution also generates subsidence<br />

<strong>hazard</strong>s and presents difficult ground conditions associated<br />

with <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> clay-filled pipes and fissures.<br />

These problems <strong>in</strong>clude irregular rockhead,<br />

localized subsidence, <strong>in</strong>creased mass compressibility and<br />

dim<strong>in</strong>ished rock mass quality. Well-developed karstic<br />

groundwater flow systems occur <strong>in</strong> Dorset, near Salisbury,<br />

around Newbury and Hunger<strong>for</strong>d, and <strong>in</strong> many<br />

parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chilterns, particularly along <strong>the</strong> Palaeogene<br />

marg<strong>in</strong> between Beaconsfield and Hert<strong>for</strong>d (Waltham<br />

et al. 1997).<br />

Triassic and Permian salt<br />

In <strong>the</strong> <strong>UK</strong>, halite (rock salt) occurs ma<strong>in</strong>ly with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Triassic strata <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cheshire Bas<strong>in</strong>, and to a lesser<br />

extent <strong>in</strong> parts <strong>of</strong> Lancashire, Worcestershire and<br />

Staf<strong>for</strong>dshire. It is also present <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Permian rocks <strong>of</strong><br />

NE England and Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland (Notholt & Highley<br />

1973). Where <strong>the</strong> saliferous Triassic rocks come to<br />

outcrop, most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> halite has dissolved and <strong>the</strong> overly<strong>in</strong>g<br />

and <strong>in</strong>terbedded strata can be expected to have<br />

collapsed or foundered, produc<strong>in</strong>g a buried salt karst<br />

<strong>hazard</strong>. This represents a more difficult site classification<br />

problem than perhaps elsewhere. These areas commonly<br />

have sal<strong>in</strong>e spr<strong>in</strong>gs, <strong>in</strong>dicative <strong>of</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g salt dissolution<br />

and <strong>the</strong> active nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> karst processes. The<br />

salt deposits were exploited us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se spr<strong>in</strong>gs from<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e early Roman times to Victorian times, when more<br />

<strong>in</strong>tense and organized br<strong>in</strong>e and m<strong>in</strong>ed salt extraction<br />

was undertaken. Halite dissolves rapidly and subsidence,<br />

both natural and m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g-<strong>in</strong>duced, has affected <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong><br />

Triassic salt fields <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Cheshire, Staf<strong>for</strong>dshire<br />

(Staf<strong>for</strong>d), Worcestershire (Droitwich), coastal<br />

Lancashire (Preesall) and parts <strong>of</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland.<br />

Much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> salt m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g has been by shallow br<strong>in</strong>e<br />

extraction, <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> which also mimic <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong><br />

natural karstification <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> salt deposits.<br />

Permian salt is present at depth beneath coastal<br />

Yorkshire and Teesside. Here <strong>the</strong> salt deposits and <strong>the</strong><br />

karstification processes are much deeper than <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Triassic salt. The salt deposits are bounded up-dip by a<br />

dissolution front and collapse monocl<strong>in</strong>e (Cooper 2002).<br />

The depth <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> salt dissolution means that very few<br />

karstic features are present, ei<strong>the</strong>r as <strong>for</strong>med at or as<br />

migrated upward to <strong>the</strong> present ground surface,<br />

although some salt m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g (br<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g) subsidence has<br />

occurred.<br />

Triassic and Permian gypsum<br />

Compared with <strong>the</strong> British limestone karst, gypsum<br />

karst occurs only <strong>in</strong> relatively small areas. It is present<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> a belt 3 km wide and about 100 km long <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Permian rocks <strong>of</strong> eastern and nor<strong>the</strong>astern England<br />

(Cooper 1989). Significant thicknesses <strong>of</strong> gypsum also<br />

occur along <strong>the</strong> eastern flank <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Vale <strong>of</strong> Eden (Ryder<br />

& Cooper 1993). It also locally occurs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Triassic<br />

strata (Cooper & Saunders 1999), but <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong><br />

karstification are much less severe than <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Permian<br />

rocks. The difference is ma<strong>in</strong>ly ca<strong>use</strong>d by <strong>the</strong> thickness<br />

<strong>of</strong> gypsum <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Permian sequence and <strong>the</strong> fact that<br />

it has <strong>in</strong>terbedded dolomite aquifers. In contrast, <strong>the</strong><br />

Triassic gypsum is present ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> weakly permeable<br />

mudstone sequences. The gypsum karst has <strong>for</strong>med<br />

phreatic cave systems dissolved by water flow below <strong>the</strong><br />

piezometric surface to depths <strong>of</strong> up to 70–80 m. The<br />

rapid solubility rate <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gypsum (Klimchouk et al.<br />

1997) means that <strong>the</strong> karst is evolv<strong>in</strong>g on a human<br />

time scale. Active subsidence occurs <strong>in</strong> many places,<br />

especially around <strong>the</strong> town <strong>of</strong> Ripon (Cooper 1986,<br />

1989, 1998) and to a lesser extent <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> eastern part <strong>of</strong><br />

urban Darl<strong>in</strong>gton (Lamont-Black et al. 2002); it also<br />

occurs <strong>in</strong> several o<strong>the</strong>r locations along <strong>the</strong> outcrop<br />

<strong>for</strong>m<strong>in</strong>g a belt about 100 km long and 3–5 km wide. The

342<br />

A.R. FARRANT & A.H. COOPER<br />

active nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dissolution and <strong>the</strong>se cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g<br />

subsidence features ca<strong>use</strong> difficult ground conditions <strong>for</strong><br />

plann<strong>in</strong>g and development (Cooper & Saunders 1999;<br />

Paukštys et al. 1999; Cooper & Saunders 2002). Gypsum<br />

palaeokarst features also occur, especially along <strong>the</strong><br />

coast <strong>of</strong> NE England and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Firth <strong>of</strong> Forth <strong>of</strong>f<br />

eastern Scotland (Cooper 1997).<br />

The National <strong>Karst</strong> Database (NKD)<br />

Geologists and eng<strong>in</strong>eers have recognized <strong>for</strong> some time<br />

that <strong>the</strong> availability <strong>of</strong> geoscience basel<strong>in</strong>e <strong>data</strong> is essential<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> public safety and eng<strong>in</strong>eer<strong>in</strong>g assessment <strong>of</strong><br />

geological <strong>hazard</strong>s. Understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> severity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

problem is a prerequisite <strong>for</strong> <strong>hazard</strong> avoidance. Land<br />

developers, planners and local government can plan<br />

accord<strong>in</strong>gly and responsibly if <strong>the</strong>y can cite advance<br />

scientific–technical warn<strong>in</strong>g about <strong>the</strong> <strong>hazard</strong>s that<br />

might be present and have access to relevant geological<br />

<strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation. General guidance <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong><br />

unstable land is written <strong>in</strong>to British Government plann<strong>in</strong>g<br />

policy <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Plann<strong>in</strong>g Policy Guidance Note 14:<br />

Development on Unstable Land (Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Environment 1990), and <strong>the</strong> supplementary Annex 2<br />

(Department <strong>of</strong> Transport, Local Government & <strong>the</strong><br />

Regions 2002).<br />

When this policy was implemented, rudimentary basel<strong>in</strong>e<br />

<strong>data</strong> were collected <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>itial <strong>data</strong>base <strong>of</strong> natural<br />

cavities commissioned by <strong>the</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Environment and produced by a private geological<br />

consultancy, Applied Geology Ltd (1993). This is now<br />

held, and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed as a legacy <strong>data</strong>set, by <strong>the</strong> British<br />

Geological Survey (BGS), and is <strong>of</strong>fered as a technical<br />

service by Peter Brett Associates, a private geological<br />

consultancy. This study demonstrated <strong>the</strong> national<br />

character and distribution <strong>of</strong> karst and o<strong>the</strong>r natural<br />

cavities, based on documentary evidence from a wide<br />

variety <strong>of</strong> sources. However, <strong>in</strong> many cases <strong>the</strong> spatial<br />

record<strong>in</strong>g was not very accurate, commonly only to <strong>the</strong><br />

nearest kilometre, and <strong>in</strong> many cases was based upon<br />

only <strong>the</strong> barest m<strong>in</strong>imum <strong>of</strong> support<strong>in</strong>g <strong>data</strong>. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore,<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>data</strong>base was over-complex and many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>data</strong>base fields rema<strong>in</strong>ed empty. At <strong>the</strong> time <strong>the</strong> <strong>data</strong>base<br />

fields were recognized as essential to <strong>the</strong> best<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> mitigative prediction, and <strong>the</strong> decision<br />

was made to present <strong>the</strong> categorical need <strong>for</strong> such <strong>data</strong>,<br />

even if <strong>the</strong> bare m<strong>in</strong>imum was not <strong>the</strong>n available. S<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

that time, recent mapp<strong>in</strong>g, particularly <strong>in</strong> Chalk terra<strong>in</strong>s,<br />

has shown that <strong>the</strong> previously available <strong>data</strong> significantly<br />

under-represents <strong>the</strong> actual density <strong>of</strong> karst features<br />

now generally known to be present. Moreover,<br />

many more karst features have been identified s<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

1993, both by more recent geological mapp<strong>in</strong>g, but also<br />

through <strong>the</strong> advent <strong>of</strong> more sophisticated remote sens<strong>in</strong>g<br />

techniques such as LiDAR (light detection and rang<strong>in</strong>g).<br />

Cavers have also opened up many newly discovered cave<br />

Fig. 3. Field geologist’s field slip [OLL 131 NW (E)], compiled<br />

by F. B. A. Welch, surveyed <strong>in</strong> 1941, describ<strong>in</strong>g a stream s<strong>in</strong>k<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Upper L<strong>in</strong>colnshire Limestone Member (Jurassic), near<br />

Burton-le-Coggles [SK 9683 2595], and its response to a flood.<br />

The railway l<strong>in</strong>e is <strong>the</strong> East Coast Ma<strong>in</strong> L<strong>in</strong>e.<br />

systems, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g one <strong>of</strong> Brita<strong>in</strong>’s longest cave systems,<br />

Og<strong>of</strong> Draenen near Blaenavon (Farrant 2004), now<br />

known to be over 70 km <strong>in</strong> length, and also have<br />

discovered <strong>the</strong> country’s deepest natural vertical cavern,<br />

<strong>the</strong> 145 m deep Titan shaft <strong>in</strong> Derbyshire’s Peak Cavern.<br />

Documented speleological studies <strong>of</strong> cave systems can<br />

provide <strong>use</strong>ful <strong>in</strong>sights <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> potential <strong>for</strong> karst <strong>geo<strong>hazard</strong>s</strong><br />

to develop <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> surround<strong>in</strong>g area (Klimchouk<br />

& Lowe 2002).<br />

Much <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> relict Applied<br />

Geology <strong>data</strong>set was extracted directly from published<br />

BGS maps, memoirs and reports. However, additional<br />

<strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation now is available <strong>for</strong> systematic <strong>in</strong>tegration,<br />

as represented by historical unpublished geological field<br />

slips and notebooks held <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> National Geological<br />

Data Centre <strong>in</strong> Keyworth. <strong>Karst</strong> features have been<br />

recorded rout<strong>in</strong>ely by field geologists on <strong>the</strong>ir field slips<br />

s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> Survey’s <strong>in</strong>ception <strong>in</strong> 1835. However, <strong>the</strong>y have<br />

only rarely been depicted on published map and reports,<br />

and <strong>the</strong> <strong>data</strong> conta<strong>in</strong>ed on <strong>the</strong>m can be difficult to access.<br />

In 2000, as part <strong>of</strong> a drive to make its <strong>data</strong>sets more<br />

accessible <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> common good, <strong>the</strong> BGS embarked on<br />

construct<strong>in</strong>g a more comprehensive geographic <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation<br />

system (GIS) and <strong>data</strong>base <strong>of</strong> karst <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation<br />

(Cooper et al. 2001), from which <strong>the</strong> National <strong>Karst</strong><br />

Database was set up. The aim was to retrieve <strong>the</strong> karst<br />

<strong>data</strong> conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> field slips and on paper maps held<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> archives, and make <strong>the</strong>m accessible <strong>in</strong> a GIS<br />

<strong>for</strong>mat. The BGS field slips and maps have now been<br />

scanned and many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m geo-rectified so that <strong>the</strong>y can<br />

be viewed via an <strong>in</strong>-ho<strong>use</strong> customized GIS system. An<br />

example <strong>of</strong> a historical field slip from L<strong>in</strong>colnshire is<br />

shown <strong>in</strong> Figure 3.<br />

Additional f<strong>in</strong>e-scale karst <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation is now be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

rout<strong>in</strong>ely ga<strong>the</strong>red both <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> field and from exist<strong>in</strong>g

KARST GEOHAZARDS IN THE <strong>UK</strong> 343<br />

Table 1. Datafields ga<strong>the</strong>red <strong>for</strong> s<strong>in</strong>kholes<br />

Table 2. Datafields ga<strong>the</strong>red <strong>for</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

S<strong>in</strong>kholes, record item<br />

Parameters<br />

Spr<strong>in</strong>gs, record item<br />

Parameters<br />

S<strong>in</strong>khole name<br />

Size<br />

Type<br />

Shape<br />

Surface pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

Infill deposits<br />

Subsidence type<br />

Evidence <strong>of</strong> quarry<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Primary <strong>data</strong> source<br />

Reliability<br />

Property damage<br />

Oldest recorded subsidence<br />

Intermediate subsidence events<br />

Most recent subsidence<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>data</strong><br />

References<br />

DoE, Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Environment.<br />

Free text<br />

Size x, Size y, Size z, metres<br />

Compound, collapse,<br />

suffusion, solution, no <strong>data</strong>,<br />

buried<br />

Round, oval, irregular,<br />

modified, compound, no<br />

<strong>data</strong><br />

Pipe, cone, <strong>in</strong>verted cone,<br />

saucer, complex, levelled<br />

(filled), no <strong>data</strong><br />

British Geological Survey<br />

rock and stratigraphical<br />

codes with thicknesses<br />

Gradual, episodic,<br />

<strong>in</strong>stantaneous, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Yes, no, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Field mapp<strong>in</strong>g, air-photo,<br />

site <strong>in</strong>vestigation, <strong>data</strong>base,<br />

maps and surveys,<br />

literature, Lidar remote<br />

sens<strong>in</strong>g, DoE <strong>data</strong>base, no<br />

<strong>data</strong><br />

Good, probable, poor, no<br />

<strong>data</strong><br />

Yes, no, no <strong>data</strong><br />

dd/mm/yyyy<br />

dd/mm/yyyy<br />

dd/mm/yyyy<br />

dd/mm/yyyy<br />

Free text<br />

documentary <strong>data</strong> sources. The <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation ga<strong>the</strong>red<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g fieldwork is recorded ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>digital</strong>ly on portable<br />

tablet computers or on pro <strong>for</strong>ma field <strong>data</strong> sheets<br />

organized with <strong>the</strong> same <strong>data</strong>fields as <strong>the</strong> GIS and<br />

its underly<strong>in</strong>g <strong>data</strong>base. Documentary <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation is<br />

ga<strong>the</strong>red from exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>data</strong>sets such as scanned and<br />

geo-rectified copies <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> geologists’ field maps, historical<br />

and modern geo-rectified Ordnance Survey maps,<br />

cave surveys, academic papers and historical documents.<br />

The <strong>data</strong> are systematically entered <strong>in</strong>to a customized<br />

GIS system, <strong>in</strong>itially achieved us<strong>in</strong>g ArcView3 (Cooper<br />

et al. 2001), but now us<strong>in</strong>g ArcGIS9. The po<strong>in</strong>t-specific<br />

<strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation and <strong>data</strong>base tables are <strong>the</strong>n copied to<br />

centralized Oracle <strong>data</strong>bases. O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>data</strong>sets such as<br />

<strong>the</strong> Applied Geology <strong>data</strong>base and <strong>the</strong> Mendip Cave<br />

Registry <strong>data</strong> are be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>use</strong>d to identify o<strong>the</strong>r sources <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation where relevant.<br />

Data on five ma<strong>in</strong> types <strong>of</strong> karst feature are collected:<br />

s<strong>in</strong>kholes (or dol<strong>in</strong>es), stream s<strong>in</strong>ks, caves, spr<strong>in</strong>gs, and<br />

<strong>in</strong>cidences <strong>of</strong> associated damage to build<strong>in</strong>gs, roads,<br />

bridges and o<strong>the</strong>r eng<strong>in</strong>eered works. The details ga<strong>the</strong>red<br />

are listed <strong>in</strong> Tables 1–5 (<strong>for</strong> s<strong>in</strong>kholes, spr<strong>in</strong>gs,<br />

Spr<strong>in</strong>g name Free text<br />

Elevation<br />

Metres<br />

Situation<br />

Open surface, borehole, concealed,<br />

submerged, submar<strong>in</strong>e, underground<br />

<strong>in</strong>let, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Proven dye trace Yes, no<br />

Flow<br />

Ephemeral, fluctuat<strong>in</strong>g, constant,<br />

flood overflow, ebb<strong>in</strong>g and flow<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

no <strong>data</strong><br />

Water type<br />

Normal–fresh, sal<strong>in</strong>e, sulphate,<br />

tufaceous, o<strong>the</strong>r m<strong>in</strong>eral, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Size<br />

Trickle, small stream, medium stream,<br />

large stream, small river, medium<br />

river, large river, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Primary <strong>data</strong> source Field mapp<strong>in</strong>g, air-photo, site<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigation, <strong>data</strong>base, maps and<br />

surveys, literature, Lidar remote<br />

sens<strong>in</strong>g, DoE <strong>data</strong>base, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Artesian<br />

Yes, no, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Thermal<br />

Yes, no, no <strong>data</strong><br />

<strong>Karst</strong>ic<br />

Yes, no, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Uses<br />

None, public, agricultural, <strong>in</strong>dustrial,<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Character<br />

S<strong>in</strong>gle discrete, multiple discrete,<br />

diff<strong>use</strong>, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Reliability<br />

Good, probable, poor, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Estimated discharge Litres per second (l s 1 )<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>data</strong><br />

dd/mm/yyyy<br />

References<br />

Free text<br />

stream s<strong>in</strong>ks, caves and build<strong>in</strong>g damage, respectively).<br />

For each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se <strong>data</strong>sets, <strong>in</strong> common with all BGS<br />

<strong>data</strong>bases, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation added to <strong>the</strong> system<br />

has common header <strong>data</strong> <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g National Grid<br />

coord<strong>in</strong>ates, date entered, <strong>use</strong>r number and reliability.<br />

For s<strong>in</strong>kholes, <strong>the</strong> <strong>data</strong> can be entered ei<strong>the</strong>r as a<br />

polygon cover<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> known extent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> feature, where<br />

spatial <strong>data</strong> exist, or as a po<strong>in</strong>t, where <strong>the</strong> s<strong>in</strong>khole is too<br />

small to be represented or if no spatial <strong>data</strong> are available.<br />

The type description <strong>of</strong> s<strong>in</strong>khole is adapted from<br />

<strong>the</strong> classification <strong>of</strong> Culshaw & Waltham (1987). The<br />

size <strong>of</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>gs and stream s<strong>in</strong>ks is necessarily subjective,<br />

depend<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> year and ra<strong>in</strong>fall, but a proxy<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> average flow can be obta<strong>in</strong>ed from <strong>the</strong> observed<br />

channel width and depth (<strong>of</strong> both <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluent and<br />

effluent channels). For <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> historical <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation<br />

ga<strong>the</strong>red from published maps and geologists’<br />

field maps and slips, no precise description <strong>of</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>g or<br />

stream s<strong>in</strong>k flow is available <strong>for</strong> direct entry to <strong>the</strong><br />

NKD. In many cases, some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>data</strong>set entries can be<br />

estimated or obta<strong>in</strong>ed from o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>data</strong> sources. In<strong>for</strong>mation<br />

ga<strong>the</strong>red <strong>for</strong> caves is also collected as ei<strong>the</strong>r<br />

po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>data</strong> <strong>for</strong> cave entrances, or, if <strong>the</strong>y are known, as<br />

l<strong>in</strong>ear <strong>data</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> approximate centre l<strong>in</strong>es <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> caves

344<br />

Table 3. Datafields ga<strong>the</strong>red <strong>for</strong> stream s<strong>in</strong>ks<br />

A.R. FARRANT & A.H. COOPER<br />

Table 5. Datafields ga<strong>the</strong>red <strong>for</strong> property damage<br />

Stream s<strong>in</strong>ks;<br />

record item<br />

Parameters<br />

Property damage,<br />

record item<br />

Parameters<br />

S<strong>in</strong>k name<br />

Free text<br />

Elevation<br />

Metres<br />

Proven dye traces Yes, no, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Morphology Discrete compound, discrete s<strong>in</strong>gle<br />

s<strong>in</strong>k, diff<strong>use</strong> s<strong>in</strong>k, los<strong>in</strong>g stream,<br />

ponded s<strong>in</strong>k, cave entrance,<br />

concealed s<strong>in</strong>k, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Flow<br />

Perennial, <strong>in</strong>termittent, ephemeral<br />

(flood), estavelle, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Size<br />

Trickle, small stream, medium<br />

stream, large stream, small river,<br />

medium river, large river, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Primary <strong>data</strong> source Field mapp<strong>in</strong>g, air-photo, site<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigation, <strong>data</strong>base, maps and<br />

surveys, literature, Lidar remote<br />

sens<strong>in</strong>g, DoE <strong>data</strong>base, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Reliability<br />

Good, probable, poor, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Estimated discharge Litres per second (l s 1 )<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>data</strong><br />

Free text<br />

References<br />

Free text<br />

Table 4. Datafields ga<strong>the</strong>red <strong>for</strong> natural cavities<br />

Natural cavities,<br />

record item<br />

Cavity name<br />

Length<br />

Vertical range<br />

Elevation<br />

Type<br />

Rock units penetrated<br />

(bedrock and superficial)<br />

Primary <strong>data</strong> source<br />

Streamway<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r entrance<br />

Evidence <strong>of</strong> m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

Reliability<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>data</strong><br />

References<br />

Parameters<br />

Free text<br />

Metres<br />

Metres<br />

Metres<br />

Open cave natural, <strong>in</strong>filled cave<br />

natural, gull cave, lava tube,<br />

boulder, peat cave, sea cave,<br />

stop<strong>in</strong>g cavity, palaeokarst,<br />

hydro<strong>the</strong>rmal borehole cavity,<br />

no <strong>data</strong><br />

British Geological Survey rock<br />

and stratigraphical codes<br />

Field mapp<strong>in</strong>g, air-photo, site<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigation, <strong>data</strong>base, maps<br />

and surveys, literature, Lidar<br />

remote sens<strong>in</strong>g, DoE <strong>data</strong>base,<br />

no <strong>data</strong><br />

Yes, no, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Yes, no, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Yes, no, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Good, probable, poor, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Free text<br />

Free text<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves. It is possible to <strong>in</strong>clude full cave surveys,<br />

but <strong>the</strong>re are <strong>of</strong>ten copyright issues that need to be<br />

addressed be<strong>for</strong>e <strong>the</strong>se <strong>data</strong> entries can be <strong>in</strong>cluded. In<br />

<strong>the</strong>se situations, <strong>the</strong> cave location is documented, and<br />

Address<br />

Postcode<br />

Elevation<br />

Damage survey 1<br />

Damage survey 2<br />

Damage survey 3<br />

Suspected ca<strong>use</strong><br />

Reliability<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r <strong>data</strong><br />

References<br />

Free text<br />

Postcode <strong>for</strong>mat<br />

Metres<br />

Date (dd/mm/yyyy), notes, damage<br />

rat<strong>in</strong>g (1–7)<br />

Date (dd/mm/yyyy), notes, damage<br />

rat<strong>in</strong>g (1–7)<br />

Date (dd/mm/yyyy), notes, damage<br />

rat<strong>in</strong>g (1–7)<br />

Natural subsidence, m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g subsidence,<br />

landslip, compressible fill, build<strong>in</strong>g defect<br />

Good, probable, poor, no <strong>data</strong><br />

Free text<br />

Free text<br />

reference to <strong>the</strong> survey made <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> reference table where<br />

appropriate. Many sites are multiple features; <strong>for</strong><br />

example, many stream s<strong>in</strong>ks are also cave entrances,<br />

whereas s<strong>in</strong>kholes might also be sites <strong>of</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g or<br />

<strong>in</strong>frastructure damage.<br />

S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> <strong>data</strong>base was set up <strong>in</strong> 2002, much <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation<br />

has been added to <strong>the</strong> system. Data cover<strong>in</strong>g<br />

most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> evaporite karst areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>UK</strong> have now<br />

been added, along with <strong>data</strong> cover<strong>in</strong>g about 60% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Chalk, and 30% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Carboniferous Limestone outcrops.<br />

To date, over 800 caves, 1300 stream s<strong>in</strong>ks, 5600<br />

spr<strong>in</strong>gs and 10 000 s<strong>in</strong>kholes have been recorded, and<br />

many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> classic upland karst areas have yet to be<br />

<strong>in</strong>cluded.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r karst <strong>data</strong>sets<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r karst <strong>data</strong>sets are available <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>UK</strong>, most <strong>of</strong><br />

which have been collated by members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cav<strong>in</strong>g<br />

community. These <strong>data</strong> generally cover <strong>the</strong> more wellknown<br />

Carboniferous and Devonian limestone karst<br />

areas, which conta<strong>in</strong> most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> accessible caves.<br />

The British Cav<strong>in</strong>g Association (BCA) ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s a<br />

registry <strong>of</strong> karstic sites <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>m <strong>of</strong> a National Cave<br />

Registry. It holds limited <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation about each<br />

site with l<strong>in</strong>ks to more comprehensive <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation <strong>in</strong><br />

regional cave registries ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed by regional cav<strong>in</strong>g<br />

organizations, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Mendip Cave Registry<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Cambrian Cave Registry. The Mendip Cave<br />

Registry is manned by volunteer registrars who <strong>for</strong>m <strong>the</strong><br />

membership <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> group. Its aim is to record all<br />

available <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation relat<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> caves and stone<br />

m<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> counties <strong>of</strong> Bristol, Somerset and Wiltshire.<br />

It has around 8000 documented sites <strong>of</strong> speleological<br />

<strong>in</strong>terest. These <strong>in</strong>clude caves, stream s<strong>in</strong>ks, spr<strong>in</strong>gs and<br />

sites where cavers have dug <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir ef<strong>for</strong>ts to discover<br />

new caves. The Cambrian Cave Registry is currently

KARST GEOHAZARDS IN THE <strong>UK</strong> 345<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g digitized and is scheduled to be available on-l<strong>in</strong>e<br />

sometime <strong>in</strong> 2008. The Black Mounta<strong>in</strong> Cave Register,<br />

part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cambrian Cave Registry, <strong>use</strong>d to be accessible<br />

on-l<strong>in</strong>e, but is no longer available. The regional<br />

cav<strong>in</strong>g councils, supported by <strong>the</strong> BCA, also hold <strong>data</strong>bases<br />

conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation about caves and access<br />

arrangements.<br />

The Cave Database (http://www.cave<strong>data</strong>base.co.uk/)<br />

is an open access website to which anyone can add<br />

cave-related l<strong>in</strong>ks. However, its coverage is patchy, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>data</strong> are not complete. In addition, <strong>the</strong> website may<br />

be at risk <strong>of</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g compromised by <strong>the</strong> gratuitous<br />

<strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>of</strong> l<strong>in</strong>ks that are not cave related, or <strong>data</strong> that<br />

have not been checked.<br />

CAPRA, <strong>the</strong> Cave Archaeology and Palaeontology<br />

Research Archive based <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Sheffield,<br />

has compiled a gazetteer <strong>of</strong> English, Scottish and Welsh<br />

caves, fissures and rock-shelters that conta<strong>in</strong> human<br />

rema<strong>in</strong>s. This is available on <strong>the</strong> CAPRA website<br />

(Chamberla<strong>in</strong> & Williams 1999, 2000a, b).<br />

The Chelsea Spelaeological Society has compiled a<br />

<strong>data</strong>set <strong>of</strong> natural and man-made cavities <strong>in</strong> SE<br />

England. These have been published as a series <strong>of</strong><br />

paperback publications (some co-authored with <strong>the</strong><br />

Kent Underground Research Group) that are available<br />

from <strong>the</strong> Society. Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>data</strong> relate to dene-holes<br />

and Chalk m<strong>in</strong>es, but some natural chalk caves are<br />

<strong>in</strong>cluded, such as those at Beachy Head <strong>in</strong> Sussex<br />

(Waltham et al. 1997).<br />

Many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lesser known karst areas, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g much<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chalk outcrop, are not covered by <strong>the</strong>se schemes.<br />

These areas still conta<strong>in</strong> significant densities <strong>of</strong> karst<br />

<strong>geo<strong>hazard</strong>s</strong>, and are commonly located <strong>in</strong> more densely<br />

populated areas. Moreover, a significant drawback <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se <strong>data</strong>bases is that <strong>the</strong>y only provide <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation on<br />

known karst features. Predict<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> whereabouts <strong>of</strong><br />

karst features such as buried s<strong>in</strong>kholes and undiscovered<br />

near-surface cavities is more difficult. Comb<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g available<br />

basel<strong>in</strong>e karst <strong>data</strong> with o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>digital</strong> spatial <strong>data</strong>,<br />

such as bedrock and superficial geology, superficial<br />

deposit thickness and <strong>digital</strong> terra<strong>in</strong> models, with<strong>in</strong> a<br />

GIS can provide a powerful tool <strong>for</strong> predict<strong>in</strong>g karst<br />

<strong>geo<strong>hazard</strong>s</strong>.<br />

National <strong>Karst</strong> Geo<strong>hazard</strong> GIS<br />

(GeoSure)<br />

Over <strong>the</strong> past decade, <strong>the</strong> BGS has <strong>in</strong>vested considerable<br />

resources <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> production <strong>of</strong> <strong>digital</strong> geological map<br />

<strong>data</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>UK</strong>. Digital geological maps (DiGMap) are<br />

now available <strong>for</strong> most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country at <strong>the</strong> 1:50 000<br />

scale, and complete coverage at <strong>the</strong> 1:250 000 and<br />

1:625 000 scales. A significant part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country is also<br />

covered at <strong>the</strong> 1:10 000 scale. All <strong>the</strong>se <strong>data</strong>sets <strong>in</strong>clude<br />

<strong>the</strong> bedrock, and <strong>the</strong> 1:625 000, 1:50 000 and 1:10 000<br />

scale <strong>data</strong>sets also <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>data</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> superficial<br />

deposits. Each polygon <strong>of</strong> <strong>digital</strong> geological <strong>data</strong> is<br />

attributed with a two-part code (<strong>the</strong> LEX-ROCK code)<br />

that gives its stratigraphy and its lithology. For example,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Sea<strong>for</strong>d Chalk Formation is represented by <strong>the</strong> code<br />

SECK_CHLK, whereas <strong>the</strong> Carboniferous Gully Oolite<br />

Formation has <strong>the</strong> code GUO_OOLM. A comprehensive<br />

list <strong>of</strong> all <strong>the</strong> LEX codes <strong>use</strong>d can be found <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

BGS Lexicon <strong>of</strong> Named Rock Units, which is available<br />

on <strong>the</strong> Internet at http://www.bgs.ac.uk/lexicon/ lexicon_<br />

<strong>in</strong>tro.html. Here, each named unit will eventually be<br />

def<strong>in</strong>ed and its upper and lower boundaries described.<br />

The lithological codes (ROCK) are based on <strong>the</strong> BGS<br />

Rock Classification Scheme, and are also expla<strong>in</strong>ed and<br />

listed on <strong>the</strong> Internet at http://www.bgs.ac.uk/<strong>data</strong>/<br />

dictionaries.html and can be searched by name or code.<br />

The availability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>digital</strong> geological maps has<br />

allowed <strong>the</strong> BGS to produce a set <strong>of</strong> predictive <strong>data</strong>sets<br />

<strong>for</strong> geological <strong>hazard</strong>s, known and marketed as<br />

‘GeoSure’. Several derived <strong>data</strong>sets have been produced<br />

us<strong>in</strong>g a variety <strong>of</strong> algorithms to provide geo<strong>hazard</strong><br />

<strong>data</strong> <strong>for</strong> soluble rocks (dissolution), landslides (slope<br />

<strong>in</strong>stability), compressible ground, collapsible rocks,<br />

shr<strong>in</strong>k–swell deposits and runn<strong>in</strong>g sand.<br />

The GeoSure dissolution <strong>data</strong>set can be <strong>use</strong>d to<br />

identify areas where <strong>the</strong>re is potential <strong>for</strong> a range <strong>of</strong><br />

karstic features to develop. Such features <strong>in</strong>clude potential<br />

<strong>geo<strong>hazard</strong>s</strong> such as s<strong>in</strong>kholes, dissolution pipes,<br />

natural cavities and areas prone to dissolution-generated<br />

irregular rockhead, as well as hydrological features such<br />

as stream s<strong>in</strong>ks, estavelles and karstic spr<strong>in</strong>gs. It can also<br />

be <strong>use</strong>d to highlight areas where karstic groundwater<br />

flow might be significant to <strong>the</strong> public <strong>in</strong>terest. This<br />

is a dist<strong>in</strong>ct, separate <strong>data</strong>set that complements and<br />

validates <strong>the</strong> NKD.<br />

The first iterations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> GeoSure dissolution <strong>data</strong>set<br />

<strong>use</strong>d <strong>the</strong> bedrock codes as <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>for</strong> a purely<br />

lithology-based system that was enhanced by local<br />

knowledge and manual subdivision. More recently, <strong>the</strong><br />

technique <strong>use</strong>d to create <strong>the</strong> GeoSure GIS has been<br />

upgraded, and now employs a scor<strong>in</strong>g system <strong>in</strong> a GIS<br />

environment us<strong>in</strong>g a range <strong>of</strong> additional <strong>data</strong>sets. This<br />

has several advantages over <strong>the</strong> purely lithology-based<br />

system. It allows greater flexibility <strong>in</strong> rat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>hazard</strong><br />

levels, and can give a more precise <strong>hazard</strong> rat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> a<br />

given area <strong>of</strong> actual ground be<strong>in</strong>g considered <strong>for</strong> some<br />

public purpose. It allows differential weight<strong>in</strong>g to be<br />

given to different controll<strong>in</strong>g factors depend<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong><br />

underly<strong>in</strong>g karstic lithology. It is a more robust system<br />

and can be tailored to <strong>the</strong> quality <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>put <strong>data</strong>.<br />

Methods<br />

The GeoSure dissolution layer is but one <strong>of</strong> five layers <strong>of</strong><br />

geoscience <strong>data</strong> that can be brought <strong>in</strong>to consideration<br />

<strong>for</strong> general and specific land classification, plann<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

development purposes. The dissolution layer has been

346<br />

A.R. FARRANT & A.H. COOPER<br />

created by identify<strong>in</strong>g a suite <strong>of</strong> factors that can <strong>in</strong>fluence<br />

<strong>the</strong> style and degree <strong>of</strong> karst features likely to<br />

develop at any one place. Each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se factors, such as<br />

bedrock lithology, geomorphological doma<strong>in</strong> and superficial<br />

deposit thickness is represented <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> GIS as a<br />

separate <strong>the</strong>me. Each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se <strong>the</strong>mes is <strong>the</strong>n categorized<br />

and given a score, to give an <strong>in</strong>dication <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> contribution<br />

it might make to <strong>the</strong> overall degree <strong>of</strong> soluble rock<br />

<strong>hazard</strong>, <strong>in</strong> a similar manner to <strong>the</strong> more detailed sitespecific<br />

method <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Chalk proposed by Edmonds<br />

(2001). Those with a strong <strong>in</strong>fluence will have a high<br />

score, those with a slight <strong>in</strong>fluence will have a low score.<br />

Some factors, such as very thick superficial deposit<br />

cover, might even have a negative score if <strong>the</strong>y significantly<br />

reduce <strong>the</strong> particular <strong>hazard</strong> or damage potential<br />

<strong>for</strong> karst features to develop.<br />

The karst geo<strong>hazard</strong> layer is created <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> GIS<br />

s<strong>of</strong>tware by <strong>in</strong>tersect<strong>in</strong>g all <strong>the</strong> <strong>data</strong>sets <strong>in</strong>to one, creat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

a mosaic <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>tersected polygons. For each result<strong>in</strong>g<br />

polygon, <strong>the</strong> sum total <strong>of</strong> each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> contribut<strong>in</strong>g<br />

factors is <strong>the</strong>n <strong>use</strong>d to give an overall potential <strong>hazard</strong><br />

score. These scores can <strong>the</strong>n be categorized to give a<br />

<strong>hazard</strong> rat<strong>in</strong>g (A–E) <strong>for</strong> a particular area. The <strong>hazard</strong><br />

rat<strong>in</strong>g categories can be tailored to suit <strong>the</strong> quantitative<br />

needs <strong>of</strong> different end-<strong>use</strong>rs; <strong>for</strong> example, a high <strong>hazard</strong><br />

rat<strong>in</strong>g important <strong>for</strong> those plann<strong>in</strong>g a tunnell<strong>in</strong>g scheme<br />

might not be pert<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>for</strong> a home owner. The geological<br />

manifestations <strong>of</strong> carbonate karst compared with those<br />

<strong>of</strong> gypsum and salt karsts are different, so <strong>the</strong> evaporites<br />

have a slightly different set <strong>of</strong> determ<strong>in</strong>ative parameters<br />

and are thus s<strong>of</strong>tware-calculated separately. In addition,<br />

<strong>the</strong> actual scores <strong>use</strong>d <strong>for</strong> each factor can be updated<br />

when new or more detailed basel<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation, such as<br />

a new version <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>digital</strong> geological map, becomes<br />

available.<br />

Bedrock lithology<br />

The type, style and scale <strong>of</strong> karst geo<strong>hazard</strong> is strongly<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluenced by its <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic bedrock lithology, which can<br />

commonly be <strong>use</strong>d as a proxy <strong>for</strong> a particular rock<br />

unit’s overall mass fracture properties and hydrological<br />

characteristics.<br />

All <strong>the</strong> known soluble and karstic rocks (with <strong>the</strong><br />

exception <strong>of</strong> units conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g gypsum and halite, which<br />

are described below) were extracted from <strong>the</strong> BGS<br />

DiGMap 1:50 000 scale <strong>digital</strong> geological <strong>data</strong>base<br />

and grouped on <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir LEX-ROCK codes<br />

<strong>in</strong>to four broad lithological group<strong>in</strong>gs: Cretaceous<br />

chalks; Palaeozoic limestones (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Neoproterozoic<br />

metacarbonates); Jurassic limestones and oolites, and<br />

Triassic conglomerates and Permian dolomites.<br />

These broad group<strong>in</strong>gs reflect <strong>the</strong> different style <strong>of</strong><br />

karst landscape evolution that <strong>the</strong>se rock units support.<br />

For example, <strong>the</strong> style and type <strong>of</strong> karst features developed<br />

on <strong>the</strong> Chalk is very different from that developed<br />

on <strong>the</strong> Carboniferous Limestone.<br />

Each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> 480 geological units extracted from <strong>the</strong><br />

DiGMap <strong>data</strong>base was <strong>the</strong>n given a score based on its<br />

LEX-ROCK code. Those rock units that ei<strong>the</strong>r are<br />

known to be, or have <strong>the</strong> potential to be, highly karstic,<br />

such as some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Carboniferous Limestone units, are<br />

given a high score, whereas those rock units that are less<br />

karstic, but still with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> range <strong>of</strong> ‘soluble’ rocks, such<br />

as some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Jurassic oolites, have a lower score. The<br />

rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> guid<strong>in</strong>g factor <strong>data</strong>sets were <strong>the</strong>n cut aga<strong>in</strong>st<br />

this modified bedrock layer to create <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>al <strong>hazard</strong><br />

layer specific to <strong>the</strong> karst areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>UK</strong>. The scores<br />

<strong>use</strong>d to weight each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> guid<strong>in</strong>g factors can be<br />

adjusted slightly accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> lithological group<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

to reflect <strong>the</strong> style and degree <strong>of</strong> karstification, as well as<br />

on a local basis, where and if new, project or <strong>use</strong>-related<br />

<strong>data</strong> are available.<br />

In addition, a set <strong>of</strong> typically non-soluble lithologies<br />

that are known to host karstic features were also<br />

extracted. In areas <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terstratal karst, <strong>the</strong> overly<strong>in</strong>g<br />

cover rocks are liable to subside <strong>in</strong>to cavities <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

underly<strong>in</strong>g limestone, creat<strong>in</strong>g cover-collapse s<strong>in</strong>kholes.<br />

The Twrch Sandstone Formation (part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Marros<br />

Group, which replaces <strong>the</strong> term Millstone Grit <strong>in</strong> South<br />

Wales) is a classic example <strong>of</strong> a non-soluble lithology<br />

that locally hosts s<strong>in</strong>kholes and stream s<strong>in</strong>ks. Some<br />

mapped <strong>for</strong>mations conta<strong>in</strong> both soluble and nonsoluble<br />

lithologies, and this is reflected <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> GIS by <strong>the</strong><br />

overall score given to <strong>the</strong> particular <strong>for</strong>mation. More<br />

detailed geological <strong>data</strong>sets may allow fur<strong>the</strong>r subdivision<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual soluble or non-soluble lithologies<br />

with<strong>in</strong> a particular <strong>for</strong>mation.<br />

Superficial deposit doma<strong>in</strong>s<br />

The superficial geology <strong>of</strong> an area has a strong <strong>in</strong>fluence<br />

on <strong>the</strong> development potential <strong>of</strong> karst features. Areas<br />

underly<strong>in</strong>g only a th<strong>in</strong> cover <strong>of</strong> superficial deposits<br />

commonly have a greater <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> near-surface karst<br />

features such as suffosion s<strong>in</strong>kholes. This situation is<br />

ca<strong>use</strong>d ma<strong>in</strong>ly by concentration <strong>of</strong> surface run<strong>of</strong>f on <strong>the</strong><br />

cover strata, <strong>the</strong>reby generat<strong>in</strong>g discrete po<strong>in</strong>t recharge<br />

<strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> susceptible underly<strong>in</strong>g bedrock and, ultimately,<br />

concentrat<strong>in</strong>g dissolution. The unconsolidated deposits<br />

can also slump and ravel <strong>in</strong>to dissolutionally enlarged<br />

fissures <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> underly<strong>in</strong>g limestone, creat<strong>in</strong>g dissolution<br />

pipes, cavities and, ultimately, s<strong>in</strong>kholes. These types <strong>of</strong><br />

s<strong>in</strong>khole are common <strong>in</strong> areas with a th<strong>in</strong> cover <strong>of</strong><br />

glacial deposits overly<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Carboniferous Limestone,<br />

as <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Yorkshire Dales, or areas <strong>of</strong> clay-with-fl<strong>in</strong>ts<br />

over <strong>the</strong> Chalk <strong>in</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn England.<br />

Details <strong>of</strong> all <strong>the</strong> superficial deposits that overlie<br />

soluble bedrock polygons were extracted from <strong>the</strong> BGS<br />

DiGMap 1:50 000 scale <strong>digital</strong> geological <strong>data</strong>base and<br />

cut aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> soluble bedrock polygons. The superficial<br />

polygons were <strong>the</strong>n grouped <strong>in</strong>to a set <strong>of</strong> superficial<br />

deposit doma<strong>in</strong>s that reflect <strong>the</strong>ir genetic orig<strong>in</strong>s<br />

(Table 6), based on LEX-ROCK codes. Each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se

KARST GEOHAZARDS IN THE <strong>UK</strong> 347<br />

Table 6. Superficial deposit doma<strong>in</strong> group<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

Doma<strong>in</strong><br />

Unmantled doma<strong>in</strong><br />

Mar<strong>in</strong>e doma<strong>in</strong><br />

Raised beach doma<strong>in</strong><br />

River valley doma<strong>in</strong><br />

River terrace doma<strong>in</strong><br />

Wea<strong>the</strong>red mantled doma<strong>in</strong><br />

Dry valley doma<strong>in</strong><br />

Glacial doma<strong>in</strong><br />

doma<strong>in</strong>s is given a score. In <strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> mar<strong>in</strong>e superficial<br />

deposits <strong>the</strong> score is negative, which reflects <strong>the</strong><br />

lower potential <strong>for</strong> karst to develop <strong>in</strong> areas covered by<br />

mar<strong>in</strong>e deposits such as estuar<strong>in</strong>e alluvium.<br />

The accuracy <strong>of</strong> both <strong>the</strong> solid and superficial polygons<br />

is based on <strong>the</strong> basel<strong>in</strong>e geological <strong>data</strong>, which <strong>in</strong><br />

turn are dependent on <strong>the</strong> quality and quantity <strong>of</strong><br />

exposure, and <strong>the</strong> antiquity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> orig<strong>in</strong>al geological<br />

mapp<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Superficial thickness<br />

Characteristics<br />

Areas with no superficial<br />

cover, or where <strong>the</strong> cover has<br />

been eroded away<br />

All mar<strong>in</strong>e and <strong>in</strong>tertidal<br />

superficial deposits<br />

All types <strong>of</strong> raised beach<br />

deposits<br />

Fluvial deposits such as<br />

alluvium, valley peat and<br />

valley gravels<br />

All types <strong>of</strong> river terrace<br />

deposits<br />

Residual and/or wea<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>g<br />

deposits such as clay-withfl<strong>in</strong>ts,<br />

loessic deposits and<br />

cover-sands, and hill peat<br />

Head, coombe and valley<br />

gravels<br />

Tills and glacial mora<strong>in</strong>e<br />

deposits<br />

Each superficial unit will also have a score depend<strong>in</strong>g<br />

upon how thick it is. Areas with a very th<strong>in</strong> superficial<br />

cover will have a high score, reflect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> greater<br />

likelihood <strong>of</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t recharge effects and <strong>the</strong>ir subsequent<br />