Clovis, Tanya. - WIDECAST

Clovis, Tanya. - WIDECAST

Clovis, Tanya. - WIDECAST

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Clovis</strong>, <strong>Tanya</strong>. 2005. Sea Turtle Manual for Nesting Beach Hotels, Staff, Security and Tour Guides. Developed by SOS Tobago with<br />

assistance from the Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network (<strong>WIDECAST</strong>). Sponsored by the Travel Foundation. Tobago.<br />

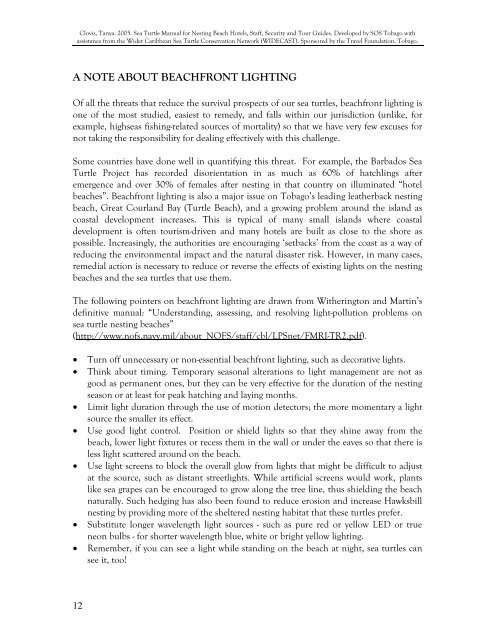

A NOTE ABOUT BEACHFRONT LIGHTING<br />

Of all the threats that reduce the survival prospects of our sea turtles, beachfront lighting is<br />

one of the most studied, easiest to remedy, and falls within our jurisdiction (unlike, for<br />

example, highseas fishing-related sources of mortality) so that we have very few excuses for<br />

not taking the responsibility for dealing effectively with this challenge.<br />

Some countries have done well in quantifying this threat. For example, the Barbados Sea<br />

Turtle Project has recorded disorientation in as much as 60% of hatchlings after<br />

emergence and over 30% of females after nesting in that country on illuminated “hotel<br />

beaches”. Beachfront lighting is also a major issue on Tobago’s leading leatherback nesting<br />

beach, Great Courland Bay (Turtle Beach), and a growing problem around the island as<br />

coastal development increases. This is typical of many small islands where coastal<br />

development is often tourism-driven and many hotels are built as close to the shore as<br />

possible. Increasingly, the authorities are encouraging ‘setbacks’ from the coast as a way of<br />

reducing the environmental impact and the natural disaster risk. However, in many cases,<br />

remedial action is necessary to reduce or reverse the effects of existing lights on the nesting<br />

beaches and the sea turtles that use them.<br />

The following pointers on beachfront lighting are drawn from Witherington and Martin’s<br />

definitive manual: “Understanding, assessing, and resolving light-pollution problems on<br />

sea turtle nesting beaches”<br />

(http://www.nofs.navy.mil/about_NOFS/staff/cbl/LPSnet/FMRI-TR2.pdf).<br />

• Turn off unnecessary or non-essential beachfront lighting, such as decorative lights.<br />

• Think about timing. Temporary seasonal alterations to light management are not as<br />

good as permanent ones, but they can be very effective for the duration of the nesting<br />

season or at least for peak hatching and laying months.<br />

• Limit light duration through the use of motion detectors; the more momentary a light<br />

source the smaller its effect.<br />

• Use good light control. Position or shield lights so that they shine away from the<br />

beach, lower light fixtures or recess them in the wall or under the eaves so that there is<br />

less light scattered around on the beach.<br />

• Use light screens to block the overall glow from lights that might be difficult to adjust<br />

at the source, such as distant streetlights. While artificial screens would work, plants<br />

like sea grapes can be encouraged to grow along the tree line, thus shielding the beach<br />

naturally. Such hedging has also been found to reduce erosion and increase Hawksbill<br />

nesting by providing more of the sheltered nesting habitat that these turtles prefer.<br />

• Substitute longer wavelength light sources - such as pure red or yellow LED or true<br />

neon bulbs - for shorter wavelength blue, white or bright yellow lighting.<br />

• Remember, if you can see a light while standing on the beach at night, sea turtles can<br />

see it, too!<br />

12