exhibition brochure (PDF) - Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film ...

exhibition brochure (PDF) - Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film ...

exhibition brochure (PDF) - Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The 43rd Annual<br />

University of<br />

California, <strong>Berkeley</strong><br />

Master of Fine <strong>Art</strong>s<br />

Graduate Exhibition<br />

may 17–june 16, 2013

Dru Anderson<br />

Dusadee Pang Huntrakul<br />

Erin Colleen Johnson<br />

Sahar Khoury<br />

Jess Rowl<strong>and</strong><br />

Sean Talley

The 43rd Annual<br />

University of California,<br />

<strong>Berkeley</strong> Master of Fine <strong>Art</strong>s<br />

Graduate Exhibition<br />

Each year the University of California, <strong>Berkeley</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> <strong>Film</strong><br />

Archive joins forces with the Department of <strong>Art</strong> Practice to present the annual<br />

Master of Fine <strong>Art</strong>s Graduate Exhibition. For this, its 43rd iteration, we have<br />

taken this collaborative ethos a step further: we invited a Ph.D. c<strong>and</strong>idate in the<br />

History of <strong>Art</strong> Department, Yasmine Chtchourova-Van Pee, to write texts that place<br />

each graduating artist’s work in the broader contexts of art <strong>and</strong> cultural history.<br />

Walking into the <strong>exhibition</strong>, visitors may be struck by the diversity of materials<br />

<strong>and</strong> concepts on display. However, this is not surprising given the strong alliances<br />

between <strong>Art</strong> Practice <strong>and</strong> other UC <strong>Berkeley</strong> departments. As a result of<br />

interdisciplinary crossover, installations tend to be less object-based <strong>and</strong> more<br />

totalizing environments; some seemingly emerge from the residue of the studio<br />

floor, while others reconsider how to use the pedestals <strong>and</strong> furniture of traditional<br />

gallery display.<br />

I encourage you to delve into the <strong>exhibition</strong> with this <strong>brochure</strong> in h<strong>and</strong>. The latter<br />

can never fully reveal the former, but it is our hope that another, more interstitial<br />

experience seeps in from between these lines.<br />

Dena Beard assistant curator

Dru Anderson<br />

Dru Anderson’s elaborate installations of carefully rendered <strong>and</strong> lovingly detailed<br />

drawings, pastels, oils, <strong>and</strong> watercolors provide visual environments of seemingly<br />

inexhaustible extension. The artist’s prodigious output (she finishes at<br />

least three works each day <strong>and</strong> often many more) is driven by a longst<strong>and</strong>ing<br />

<strong>and</strong> dedicated practice of lucid dreaming. For many years now, she has been<br />

documenting a series of recurring, ever-mutating dreams. While this mode of<br />

working might appear akin to Surrealist experiments in automatism, the intent<br />

<strong>and</strong> effects of Anderson’s practice depart dramatically from this framework.<br />

While Surrealist artists reached into the realms of slumber hoping to tap into<br />

a transcendent reality—the “sur-” in Surrealism indicating a higher, surpassing<br />

level—Anderson’s works cast back from the world of dreams a universe<br />

of objects more perfect <strong>and</strong> more vivid than the reality they come to inhabit.<br />

Many of the objects Anderson depicts are taken from a feminine realm of consumer<br />

goods—feathered earrings, stiletto heels, decorative objects associated<br />

with the domestic sphere—which too easily invites the overdetermined language<br />

of gendered description. Fragility, delicacy, wealth of detail, ornament, excess,<br />

precision, naturalistic representation: all of these, too, have been part <strong>and</strong> parcel<br />

of a simplistic binary logic sequestering women’s art practices from <strong>Art</strong> proper.<br />

However, feminist art historian Marsha Meskimmon suggests that it is exactly<br />

elaboration, a seminal aspect of Anderson’s practice, that is crucial to overturning<br />

this logic. Elaboration, she notes, “thought through drawing, loses track of<br />

[regulatory] time, unlaces binary stalemates, <strong>and</strong> suggests contingent forms for<br />

the articulation of sexual difference.” In a more classical, Freudian vein elaboration<br />

also emerges as the most radical aspect of the dreamwork. In Freud’s canonical<br />

The Interpretation of Dreams, secondary elaboration refers to a process that<br />

takes place both in the dream <strong>and</strong> after waking, in which a “process of expansion<br />

<strong>and</strong> embellishment of detail” helps manifest latent content. As such, it is<br />

the only element of the dreamwork able to reach into dream <strong>and</strong> reality alike,<br />

bridging conscious <strong>and</strong> unconscious thought. Anderson’s intricate installations<br />

offer us both a personal paean to the feminine <strong>and</strong> the privilege to witness that<br />

most universal of human qualities: the me<strong>and</strong>ering labors of the dreaming mind.<br />

Dru Anderson: Dreamality River, 2013 (detail); mixed-media installation; dimensions variable; courtesy of the artist.

Dusadee Pang Huntrakul<br />

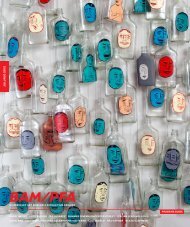

Dusadee Pang Huntrakul’s most recent body of work, slyly humorous <strong>and</strong> gleefully<br />

scatological configurations of clay figurines, might belie the scope of the artist’s<br />

interdisciplinary practice. Clay is simply the newest material to enter this artist’s<br />

protean repertoire, thanks to a fortuitous seminar taught by Bay Area ceramic artist<br />

Richard Shaw. Huntrakul’s hypertactile pieces tap into the affective qualities<br />

of surface <strong>and</strong> medium while remaining irresistibly cheeky: tiny inquisitive faces<br />

grow out of decidedly excremental bodies; wild outcrops of slipshod yet comically<br />

insistent penises beckon; clear-glazed surfaces evoke a visceral slipperiness;<br />

<strong>and</strong> miniature white-tipped rice grains turn out to be emulations of gecko poop.<br />

While midcentury critic Clement Greenberg once warned against the use of a<br />

particular medium in such a way as to “intrigue us by associations with things we<br />

can experience more authentically elsewhere,” Huntrakul’s broader artistic practice<br />

can perhaps best be characterized as an investigation into what exactly that<br />

“authentic experience” might mean now, in our post-authentic world. His emphatic,<br />

willful materiality <strong>and</strong> often labor-intensive projects—in a recent work he manually<br />

traces in pencil each page of Aihwa Ong’s book Buddha is Hiding—are meant<br />

to counteract the insect-like automatisms we all use to navigate daily life, or what<br />

the artist refers to as life’s “surface logic.” Attaining medium-specific fluency, for<br />

Huntrakul, is less an attempt to come to grips with a particular medium as medium<br />

<strong>and</strong> rather a way to reach beyond the surface logic of each city in which he finds<br />

himself—Bangkok, Los Angeles, <strong>Berkeley</strong>. It constitutes a mapping of sorts of the<br />

different scopic regimes (culturally specific ways of seeing) of these cities <strong>and</strong> an<br />

invitation for the viewer to experience, through these visceral yet ludic encounters,<br />

those habits of mind <strong>and</strong> eye that inform our own most common impulses.<br />

Dusadee Hunktral: Even Air is Not Slowing You Down, 2012; clay; 21 2/3 × 10 1/4 × 6 1/3 in.; courtesy of the artist.

Erin Colleen Johnson<br />

At heart, Erin Colleen Johnson is a storyteller, a modern-day incarnation of<br />

the bards <strong>and</strong> griots of yore who traveled the l<strong>and</strong> spinning stories <strong>and</strong> singing<br />

songs, weaving intricate tapestries of fact <strong>and</strong> fiction. Perhaps to set the appropriate<br />

tone one need but mention that Johnson considers Jorge Luis Borges,<br />

that most masterful of weavers, a kindred spirit. The kernel from which<br />

her works develop is invariably an intriguing anecdote, a harvested fact or<br />

little-known history, deepened <strong>and</strong> elaborated through extensive historical<br />

research <strong>and</strong> an engaged dialogue with various sites <strong>and</strong> collaborators.<br />

On a formal level, Johnson’s approach is fundamentally situational: the final<br />

form her installations <strong>and</strong> performances take shifts according to collaborator,<br />

topic, <strong>and</strong> means at h<strong>and</strong>. Her works range from a samizdat pirate radio station<br />

run from an Oakl<strong>and</strong> closet to highly material experiments with the filmic<br />

medium, to the most ephemeral of gestures <strong>and</strong> gatherings. A constant, however,<br />

is the deeply collaborative nature of her practice, rejecting the idea of the<br />

artist as lone creator <strong>and</strong> instead diffusing the act of imbuing meaning across<br />

a network of agents, both inside <strong>and</strong> outside the arts. Her collaborators have<br />

been as diverse as her own practice: fellow artists, a dancer, a graphologist, an<br />

ice fisherman, Morse Code operators, strangers. In that sense her newest work<br />

forms a departure of sorts. Based on boxes of h<strong>and</strong>written sermons her gr<strong>and</strong>father,<br />

a preacher, bequeathed to her, collaboration here is of necessity conceptual.<br />

Johnson is often drawn to the ephemeral, if not the outright obsolete, <strong>and</strong> to<br />

gestures that seem hopeless save to the ones enacting them. This is not a melancholic<br />

impulse, nor a simply utopian one. Like stories proper, her works are deeply<br />

generative; they create echoes <strong>and</strong> reverberations that reinscribe these forgotten<br />

acts back into the social fabric of life, like ever so many tiny chain reactions.<br />

Erin Colleen Johnson: still from Hole #1, 2013; digital video; courtesy of the artist.

Sahar Khoury<br />

Sahar Khoury’s newest works, accumulative yet delicate compositions of found<br />

<strong>and</strong> discarded materials—scraps <strong>and</strong> notes, bits of fabric, fragments of stretcher<br />

bars, repurposed canvas—emphasize touch <strong>and</strong> their status as products of the<br />

human h<strong>and</strong>. The artist’s expansive structures revel in the liminal <strong>and</strong> the inbetween:<br />

they erase the boundaries between studio <strong>and</strong> artwork, between functional<br />

space <strong>and</strong> lived space, cast <strong>and</strong> object, presence <strong>and</strong> mimesis, between<br />

wall <strong>and</strong> floor <strong>and</strong> ceiling. She turns this ontological confusion of figure <strong>and</strong><br />

ground into the very essence of her practice. The surfaces of Khoury’s works are<br />

like topographical maps born from the ever-changing ecosystem of her studio.<br />

Khoury’s working process is one of continual rearrangement. A piece might<br />

start as part of a wall—layered accumulations literally attached to <strong>and</strong> growing<br />

out of her studio’s surfaces—then live for a while as autonomous form after<br />

having been torn free, <strong>and</strong> later might be reincorporated into another composition.<br />

Other works start as papier-mâché casts, accrue layers of matter <strong>and</strong><br />

paint, <strong>and</strong> have elements screwed <strong>and</strong> unscrewed, bound, nailed, taken off,<br />

plastered over. This cycle of construction, deconstruction, <strong>and</strong> reconstruction,<br />

of displacement <strong>and</strong> relocation, celebrates not only process <strong>and</strong> artistic labor,<br />

but also partial knowledges, the tentative <strong>and</strong> the slightly off-kilter. The resultant<br />

“structural vulnerability,” to use the artist’s own words, that characterizes<br />

her finished works swaps still-potent mythologies of progress <strong>and</strong> functionality<br />

for a perennial state of impermanence <strong>and</strong>, paradoxically, a laconic thereness.<br />

Khoury’s halting <strong>and</strong> beautifully imperfect works breed an acute awareness<br />

of the present in which experiencing the now surfaces as an insurgent act.<br />

Sahar Khoury: Plates <strong>and</strong> Ball on Shelf, 2012; papier-mâché, inkjet print, leather, acrylic paint; dimensions variable;<br />

courtesy of the artist.

Jess Rowl<strong>and</strong><br />

Jess Rowl<strong>and</strong>’s artworks <strong>and</strong> installations explore how sound can be embedded<br />

<strong>and</strong> embodied in physically immediate ways, aiming to close the gap<br />

between the object that produces sound <strong>and</strong> sound itself. Her works draw on<br />

the sound-conductive properties of rather unexpected materials—copper<br />

foil, metal-based inks, photosensitive paper—<strong>and</strong> the way pattern influences<br />

signal. If that sounds rather technical, the concrete phenomenological experience<br />

of Rowl<strong>and</strong>’s works is anything but. Guided by a sincere wonder for<br />

the existential strangeness of the world (or, as the artist put it, the “intense<br />

weirdness of a bag of potato chips”) <strong>and</strong> inspired by influences as diverse<br />

as Sufi mysticism, experimental music practices, <strong>and</strong> the sequined glitter of<br />

camp culture, her works provide an almost alchemical experience—they<br />

are living systems, haptic <strong>and</strong> optic, that often react to the viewer’s body.<br />

Rowl<strong>and</strong>’s latest work is anchored around home-developed arrays of flat audio<br />

speakers, made out of sheets of copper foil cut into wild swirling motifs based<br />

on Sufi Ebru drawing or expansive fields of repetitive geometric pattern <strong>and</strong><br />

attached to clear acetate or paper backing. Their h<strong>and</strong>made aesthetic <strong>and</strong><br />

glimmering fragility evokes equal parts Joseph Albers, Eva Hesse, <strong>and</strong> Ziggy<br />

Stardust. The patterns accommodate multiple sound signals but at the same<br />

time induce varying degrees of signal loss. In the artist’s most recent installation,<br />

a custom algorithm feeds the surface arrays r<strong>and</strong>omized sound samples,<br />

some created, some scavenged from consumer culture—one consists of a<br />

robotized voice reading out the content of the artist’s spam inbox—while ambient<br />

sounds <strong>and</strong> the electromagnetic fields of arrays interacting with those of a<br />

viewer’s body generate feedback loops. This creates a highly contingent soundscape<br />

that conjures the sense of being inside an organism that reacts to you as an<br />

organism. While Rowl<strong>and</strong>’s fondness for chance, then, points towards an interest<br />

in entropy <strong>and</strong> the scrambling of information, her work also speaks of regeneration<br />

<strong>and</strong> an infectious joy in the animation <strong>and</strong> transformation of materials.<br />

Jess Rowl<strong>and</strong>: Tapestry, 2013 (detail); copper foil on acetate; 48 × 18 in.; courtesy of the artist.

Sean Talley<br />

The Oxford English Dictionary defines notation as “the process or method of<br />

representing numbers, quantities, relations, etc., by a set or system of signs or<br />

symbols, for the purpose of record or analysis.” But what if that set of signs<br />

is not unequivocal What happens when we try to engineer a purely visual<br />

language, a notational system of mere shapes <strong>and</strong> forms Sean Talley’s body<br />

of work is in part a quest for a conclusive visual semiotics, the dream at the<br />

heart of modern design <strong>and</strong> arguably of many a strain of iconic avant-garde art.<br />

Consciously stripped <strong>and</strong> understated—“tidy,” to use the artist’s word—Talley’s<br />

works repurpose the strategies <strong>and</strong> visual idiom of Minimalism to subtly different<br />

ends. An earlier set of drawings, stern black-<strong>and</strong>-white images of rectangles <strong>and</strong><br />

irregular polygons, gestures towards Minimalism’s games of permutation <strong>and</strong><br />

Gestalt, yet Talley’s intricate process complicates that simple matter-of-factness;<br />

their monolithic blackness results from the careful <strong>and</strong> painstaking application<br />

<strong>and</strong> polishing of graphite powder by h<strong>and</strong>. More recent works, modular ceramics<br />

made with the aid of an extruder <strong>and</strong> a series of colorful pencil drawings, foreground<br />

the artist’s interest in developing sets of st<strong>and</strong>ardized morphemes—his<br />

own private alphabets. Talley produces the drawings by experimenting with various<br />

ways to hold several pencils in one h<strong>and</strong> at once, the widths between marks<br />

dependent on the number of fingers separating the pencils. The sculptures, composed<br />

of st<strong>and</strong>ardized tubes of extruded clay in a set number of diameters, hold<br />

the potential to be continuously rearranged, each new iteration erasing the last.<br />

Like the Minimalist objects he draws on, his works eschew the metaphorical <strong>and</strong><br />

court a certain muteness. Yet he professes he is not so much interested in what<br />

gets lost in between each iteration, each permutation, “but in what remains.”<br />

Sean Talley: OJPSDRI, 2013; clay <strong>and</strong> medium-density fiberboard; 20 × 12 × 10 in.; courtesy of the artist <strong>and</strong> Jancar Jones<br />

Gallery, Los Angeles.

Dru Anderson lives <strong>and</strong> works in Oakl<strong>and</strong>, CA <strong>and</strong> has<br />

recently exhibited at the Tallahassee <strong>Museum</strong> of Fine <strong>Art</strong> in<br />

Florida; Worth Ryder Gallery, <strong>Berkeley</strong>; <strong>and</strong> Mills College <strong>Art</strong><br />

<strong>Museum</strong>, Oakl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Dusadee Pang Huntrakul (b. 1978) was born in Bangkok <strong>and</strong><br />

currently lives in <strong>Berkeley</strong>, CA. He has exhibited at Bangkok<br />

University <strong>Art</strong> Gallery, Thail<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> Osage Gallery, Hong Kong.<br />

Erin Johnson (b. 1985) lives in Oakl<strong>and</strong>, CA <strong>and</strong> has exhibited at<br />

Southern Exposure, Tenderloin National Forest, Root Division,<br />

Zero1 Biennial, <strong>and</strong> Shotwell Studios in San Francisco; Worth<br />

Ryder Gallery, <strong>Berkeley</strong>; <strong>and</strong> in North Carolina at Elsewhere<br />

<strong>Museum</strong>, Greensboro, <strong>and</strong> BookWorks, Asheville.<br />

Sahar Khoury (b. 1973) lives in Oakl<strong>and</strong>, CA <strong>and</strong> has exhibited<br />

at 2nd Floor Projects, Tenderloin National Forest, <strong>and</strong> Galeria<br />

de la Raza, San Francisco; New Image <strong>Art</strong>, West Hollywood;<br />

<strong>and</strong> Tangent Gallery, Detroit.<br />

Jess Rowl<strong>and</strong> is an artist, writer, <strong>and</strong> musician currently<br />

represented by Edgetone Records.<br />

Sean Talley (b. 1980) received his B.F.A. in 2003 from the San<br />

Francisco <strong>Art</strong> Institute; his work was recently shown at Jancar<br />

Jones Gallery, Los Angeles, <strong>and</strong> Important Projects, Oakl<strong>and</strong>.<br />

He lives <strong>and</strong> works in Oakl<strong>and</strong>, CA.

the annual m.f.a. <strong>exhibition</strong> at bam/pfa<br />

is made possible by the barbara berelson<br />

wiltsek endowment.<br />

Texts by Yasmine Chtchourova-Van Pee<br />

Chtchourova-Van Pee is a Ph.D. c<strong>and</strong>idate in<br />

History of <strong>Art</strong> at UC <strong>Berkeley</strong>, where she focuses<br />

on modern <strong>and</strong> contemporary African art. Her<br />

work as a writer <strong>and</strong> translator has been published<br />

in various catalogs <strong>and</strong> in publications such as<br />

Manifesta Journal, Afterall, <strong>and</strong> Modern Painters.<br />

uc berkeley art museum & pacific film archive<br />

bampfa.berkeley.edu