Ancestor Reverence in the Benguet Tradition - Philippine Culture

Ancestor Reverence in the Benguet Tradition - Philippine Culture

Ancestor Reverence in the Benguet Tradition - Philippine Culture

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

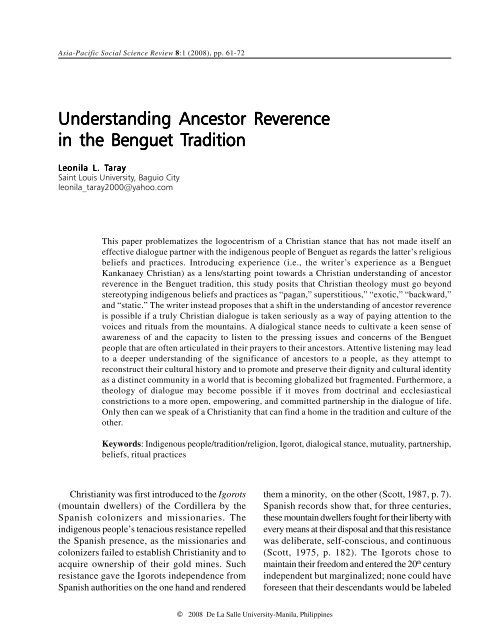

Asia-Pacific Social Science Review 8:1 (2008), pp. 61-72<br />

Understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Ancestor</strong> <strong>Reverence</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong><br />

Leonila L. Taray<br />

Sa<strong>in</strong>t Louis University, Baguio City<br />

leonila_taray2000@yahoo.com<br />

This paper problematizes <strong>the</strong> logocentrism of a Christian stance that has not made itself an<br />

effective dialogue partner with <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous people of <strong>Benguet</strong> as regards <strong>the</strong> latter’s religious<br />

beliefs and practices. Introduc<strong>in</strong>g experience (i.e., <strong>the</strong> writer’s experience as a <strong>Benguet</strong><br />

Kankanaey Christian) as a lens/start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t towards a Christian understand<strong>in</strong>g of ancestor<br />

reverence <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> tradition, this study posits that Christian <strong>the</strong>ology must go beyond<br />

stereotyp<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>digenous beliefs and practices as “pagan,” superstitious,” “exotic,” “backward,”<br />

and “static.” The writer <strong>in</strong>stead proposes that a shift <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> understand<strong>in</strong>g of ancestor reverence<br />

is possible if a truly Christian dialogue is taken seriously as a way of pay<strong>in</strong>g attention to <strong>the</strong><br />

voices and rituals from <strong>the</strong> mounta<strong>in</strong>s. A dialogical stance needs to cultivate a keen sense of<br />

awareness of and <strong>the</strong> capacity to listen to <strong>the</strong> press<strong>in</strong>g issues and concerns of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong><br />

people that are often articulated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir prayers to <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors. Attentive listen<strong>in</strong>g may lead<br />

to a deeper understand<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> significance of ancestors to a people, as <strong>the</strong>y attempt to<br />

reconstruct <strong>the</strong>ir cultural history and to promote and preserve <strong>the</strong>ir dignity and cultural identity<br />

as a dist<strong>in</strong>ct community <strong>in</strong> a world that is becom<strong>in</strong>g globalized but fragmented. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, a<br />

<strong>the</strong>ology of dialogue may become possible if it moves from doctr<strong>in</strong>al and ecclesiastical<br />

constrictions to a more open, empower<strong>in</strong>g, and committed partnership <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> dialogue of life.<br />

Only <strong>the</strong>n can we speak of a Christianity that can f<strong>in</strong>d a home <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> tradition and culture of <strong>the</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

Keywords: Indigenous people/tradition/religion, Igorot, dialogical stance, mutuality, partnership,<br />

beliefs, ritual practices<br />

Christianity was first <strong>in</strong>troduced to <strong>the</strong> Igorots<br />

(mounta<strong>in</strong> dwellers) of <strong>the</strong> Cordillera by <strong>the</strong><br />

Spanish colonizers and missionaries. The<br />

<strong>in</strong>digenous people’s tenacious resistance repelled<br />

<strong>the</strong> Spanish presence, as <strong>the</strong> missionaries and<br />

colonizers failed to establish Christianity and to<br />

acquire ownership of <strong>the</strong>ir gold m<strong>in</strong>es. Such<br />

resistance gave <strong>the</strong> Igorots <strong>in</strong>dependence from<br />

Spanish authorities on <strong>the</strong> one hand and rendered<br />

<strong>the</strong>m a m<strong>in</strong>ority, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r (Scott, 1987, p. 7).<br />

Spanish records show that, for three centuries,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se mounta<strong>in</strong> dwellers fought for <strong>the</strong>ir liberty with<br />

every means at <strong>the</strong>ir disposal and that this resistance<br />

was deliberate, self-conscious, and cont<strong>in</strong>uous<br />

(Scott, 1975, p. 182). The Igorots chose to<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir freedom and entered <strong>the</strong> 20 th century<br />

<strong>in</strong>dependent but marg<strong>in</strong>alized; none could have<br />

foreseen that <strong>the</strong>ir descendants would be labeled<br />

© 2008 De La Salle University-Manila, Philipp<strong>in</strong>es

62 ASIA-PACIFIC SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW<br />

VOL. 8 NO. 1<br />

as “m<strong>in</strong>orities.” The Spanish authorities may have<br />

failed to evangelize <strong>the</strong> Igorot People (IPs) but<br />

<strong>in</strong>stead were successful <strong>in</strong> creat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> lowlandhighland<br />

divide.<br />

The American colonial period only served to<br />

effectively re<strong>in</strong>force <strong>the</strong> majority-m<strong>in</strong>ority<br />

classification. The American colonial government<br />

occupied itself <strong>in</strong> creat<strong>in</strong>g and enact<strong>in</strong>g laws and<br />

policies that eventually legitimized <strong>in</strong>vasion,<br />

occupation, and exploitation of cultivated and<br />

<strong>in</strong>habited lands and m<strong>in</strong>eral resources <strong>in</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong><br />

and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cordillera region (see Pawid, 1987).<br />

The imposition of alien rules and policies served<br />

to weaken and, <strong>in</strong> due course, nullify resistance<br />

from <strong>the</strong> natives. In addition, <strong>the</strong> colonial government<br />

also created <strong>the</strong> Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes that<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r deepened <strong>the</strong> marg<strong>in</strong>alization of <strong>in</strong>digenous<br />

communities. It was perceived that to close <strong>the</strong> gap<br />

between <strong>the</strong> lowland Filip<strong>in</strong>os and <strong>the</strong> mounta<strong>in</strong><br />

dwellers, <strong>the</strong> Igorots had to be relocated to places<br />

near <strong>the</strong> lowlands where <strong>the</strong>y were to be civilized<br />

and christianized. Most of <strong>the</strong> Igorots chose to rema<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> land of <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors. Hence, <strong>the</strong> American<br />

Protestant and Belgian Catholic missionaries took<br />

<strong>the</strong> responsibility of plant<strong>in</strong>g and establish<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Christianity <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cordillera region dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> first<br />

decades of <strong>the</strong> 20 th century.<br />

Notably, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>troduction and development of<br />

Christianity came as a result of <strong>the</strong> missionary<br />

efforts of people com<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong> coloniz<strong>in</strong>g<br />

powers directed at <strong>in</strong>digenous communities. The<br />

Christian missionaries’ early encounter with <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>digenous culture/religion of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people<br />

<strong>in</strong> general and ancestor reverence <strong>in</strong> particular<br />

resulted <strong>in</strong> a classic tension between two religious<br />

worldviews. The early Christian missionaries<br />

viewed <strong>the</strong> local beliefs and practices as<br />

manifestations of a people’s ignorance, superstition,<br />

paganism, and backwardness. At <strong>the</strong> very worst,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se beliefs and practices were perceived to be<br />

<strong>the</strong> cause of <strong>the</strong> people’s misery and deprivation<br />

(Med<strong>in</strong>a, 2004, pp. 13-14). For <strong>the</strong> missionaries,<br />

“<strong>the</strong> Good News of Jesus Christ must be preached<br />

to save <strong>the</strong> pagan soul.”<br />

The natives <strong>the</strong>n were strongly advised to forget<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>digenous religion and to start liv<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

Christian life that was historically and culturally<br />

Western. Western education shaped <strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong>ds of<br />

young Igorots who, <strong>in</strong> time, were alienated from<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir religion/culture. The uncompromis<strong>in</strong>g efforts<br />

of <strong>the</strong> missionaries to evangelize <strong>the</strong> local<br />

<strong>in</strong>habitants resulted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> acceptance of Christianity<br />

by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> majority. Contrary to <strong>the</strong><br />

missionaries’ expectations, however, those who<br />

accepted Christianity reta<strong>in</strong>ed many of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

<strong>in</strong>digenous beliefs and practices. For example,<br />

ancestor reverence cont<strong>in</strong>ues to persist among<br />

contemporary <strong>Benguet</strong> Christians and<br />

traditionalists alike. Such persistence <strong>in</strong>dicates <strong>the</strong><br />

taken-for-granted existence of an acculturated/<br />

syncretized form of religion, creat<strong>in</strong>g tensions and<br />

conflicts which are seldom openly addressed.<br />

Never<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong> early missionary view on <strong>the</strong><br />

native condition and religion had a far-reach<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence on how <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous peoples and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

traditions are viewed from with<strong>in</strong> and from without.<br />

As one who was born <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong><br />

Kankanaey tradition, raised and educated as a<br />

Catholic Christian, and who works as a <strong>the</strong>ology<br />

<strong>in</strong>structor, I have experienced <strong>the</strong> marg<strong>in</strong>ality of<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g an Igorot and <strong>the</strong> tension of be<strong>in</strong>g positioned<br />

with<strong>in</strong> two religious worlds. However, as Kwok<br />

Puilan says, “Marg<strong>in</strong>ality should not be seen as a<br />

curse but should be seen as an <strong>in</strong>vitation to many<br />

possibilities. The struggles of marg<strong>in</strong>alized peoples<br />

for justice, and <strong>the</strong> aspirations of <strong>the</strong> underdogs of<br />

history for human dignity are profound testimonies<br />

to <strong>the</strong> unceas<strong>in</strong>g quest for freedom and peace <strong>in</strong><br />

human history” (1998, p. 278). Hence, my<br />

experience of tension and marg<strong>in</strong>ality prompted me<br />

to explore and pay attention to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong><br />

Kankanaey beliefs and practices that are<br />

associated with ancestor reverence and to delve<br />

deeper <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>gs/significances of ancestors<br />

to <strong>the</strong> contemporary issues and concerns of a<br />

marg<strong>in</strong>alized people.<br />

My exploration <strong>in</strong>volved participant observation<br />

and field notes, <strong>in</strong>formal <strong>in</strong>terviews and<br />

conversations with <strong>the</strong> Christians and traditional<br />

practitioners of Kapangan, <strong>Benguet</strong> from<br />

November 2004 to December 2005. The data<br />

ga<strong>the</strong>red from this area are enriched and placed <strong>in</strong>

UNDERSTANDING ANCESTOR REVERENCE IN THE BENGUET TRADITION<br />

TARAY, L.L. 63<br />

a wider context by pert<strong>in</strong>ent literature that would<br />

give more depth and vigor to <strong>the</strong> work. I would<br />

like to argue that <strong>the</strong> persistence of ancestor<br />

reverence among <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people is due to <strong>the</strong><br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g that ancestors play a vital role <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

fulfillment of <strong>the</strong>ir aspirations as <strong>in</strong>dividuals and as<br />

an <strong>in</strong>digenous community. <strong>Ancestor</strong>s rema<strong>in</strong> part<br />

of <strong>the</strong>ir community, <strong>the</strong>ir l<strong>in</strong>k to <strong>the</strong> div<strong>in</strong>e, and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

source of solidarity and resilience amidst <strong>the</strong> joys<br />

and perils of life. It is hoped that a well-<strong>in</strong>formed<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> role of ancestors would help<br />

dispel <strong>the</strong> misconceptions about ancestor<br />

reverence and <strong>the</strong> native religion. It is now <strong>the</strong> turn<br />

of Christian <strong>the</strong>ology to pay attention, to allow<br />

<strong>the</strong>se people to tell <strong>the</strong>ir story, and to learn from<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>digenous wisdom and spirituality just as <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Benguet</strong> people learned from <strong>the</strong> Christian<br />

missionaries.<br />

THE BENGUET INDIGENOUS RELIGION<br />

AND CHRISTIANITY:<br />

TOWARDS A DIALOGICAL ENCOUNTER<br />

Wati Longchar laments <strong>the</strong> fact that while <strong>in</strong>terreligious<br />

dialogue is tak<strong>in</strong>g place among <strong>the</strong> “major<br />

religious traditions of <strong>the</strong> world,” <strong>the</strong> advocates of<br />

<strong>in</strong>ter-faith dialogue have overlooked <strong>the</strong> rich<br />

<strong>the</strong>ological resources latent <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous traditions.<br />

In this regard he says:<br />

Interfaith dialogue has not taken <strong>the</strong> tribal<br />

peoples’ spirituality as a foundation for <strong>the</strong><br />

meet<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t for religious dialogue. It is felt<br />

that unless <strong>the</strong> perspective of <strong>the</strong> spirituality<br />

of <strong>the</strong> tribal people is made central to <strong>the</strong><br />

process of <strong>in</strong>ter-faith dialogue <strong>the</strong> tribal<br />

people and o<strong>the</strong>r marg<strong>in</strong>alized peoples will<br />

always be looked down upon as <strong>in</strong>ferior<br />

socially, culturally, and spiritually (Longchar,<br />

2000, p. 37).<br />

In a similar ve<strong>in</strong>, Elizabeth Amoah of <strong>the</strong><br />

University of Ghana claims that due to <strong>the</strong> view<br />

that primal religions are <strong>the</strong> animistic religions of<br />

primitive peoples, <strong>the</strong>y are excluded from<br />

<strong>in</strong>ternational <strong>in</strong>ter-faith dialogue (1998). Many<br />

advocates of <strong>in</strong>ter-faith dialogue have not shown<br />

any sufficient sensitivity to <strong>the</strong> tribal heritage, <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

spirituality, and <strong>the</strong>ir survival cases. They seem to<br />

be more concerned with <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ological<br />

justification for enter<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to conversations with<br />

people of different faiths (Longchar, 2000, p. 36).<br />

It is <strong>the</strong>refore worthwhile not<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> church’s<br />

recognition of <strong>in</strong>digenous religionists as partners<br />

<strong>in</strong> dialogue is none<strong>the</strong>less currently emerg<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

The urgent need to listen to <strong>the</strong> voice of <strong>the</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r is mentioned by Pope John Paul II when he<br />

writes:<br />

The church seeks to know <strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong>ds and<br />

hearts of her hearers, <strong>the</strong>ir values and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

customs, <strong>the</strong>ir problems and <strong>the</strong>ir difficulties.<br />

Once she knows and understands <strong>the</strong>se<br />

various aspects of culture, <strong>the</strong>n she can beg<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> dialogue of salvation; she can offer<br />

respectfully with charity and conviction, <strong>the</strong><br />

Good News of Redemption to all who wish<br />

to freely listen and respond (John Paul II,<br />

1990, #52).<br />

In this sense, what is needed is a Christian stance<br />

that needs to transcend its doctr<strong>in</strong>al and<br />

ecclesiastical constrictions <strong>in</strong> order to make itself<br />

available for dialogue and engagement with <strong>the</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r. What could be more enrich<strong>in</strong>g is a Christian<br />

stance that does not only engage itself with <strong>the</strong><br />

“major religions of <strong>the</strong> world” but also with<br />

<strong>in</strong>digenous ones.<br />

While <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous peoples seem not to have<br />

made a significant impact on <strong>the</strong> great mission<br />

documents of Vatican II and those of <strong>the</strong><br />

postconciliar documents, John Paul II himself had<br />

promoted a liv<strong>in</strong>g dialogue between <strong>the</strong> gospel and<br />

<strong>in</strong>digenous cultures dur<strong>in</strong>g his pastoral visits to<br />

some <strong>in</strong>digenous communities <strong>in</strong> Asia, Africa, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> Americas (Prior, 2005, p. 153). Dur<strong>in</strong>g his<br />

historic visit to <strong>the</strong> city of Baguio on 22 February<br />

1981, Pope John Paul II addressed <strong>the</strong> people of<br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Luzon and its <strong>in</strong>digenous population.<br />

…You, <strong>the</strong> Indigenous People of this beautiful<br />

nor<strong>the</strong>rn region of Luzon, as well as <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

tribal Filip<strong>in</strong>os, represent a rich diversity of

64 ASIA-PACIFIC SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW<br />

VOL. 8 NO. 1<br />

cultures which have been handed down by<br />

your parents and grandparents, and which<br />

extend back to countless generations. May<br />

you always have a deep appreciation of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

cultural treasures which div<strong>in</strong>e providence has<br />

dest<strong>in</strong>ed you to <strong>in</strong>herit. Moreover, may <strong>the</strong>se<br />

treasures which are your heritage always be<br />

respected by o<strong>the</strong>rs. May your land and your<br />

worthy family traditions and social structures<br />

be protected, preserved and enriched… you<br />

have discovered that <strong>the</strong> Gospel does not<br />

threaten <strong>the</strong> survival of your cultures or<br />

destroy your au<strong>the</strong>ntic traditions…as you<br />

face <strong>the</strong> present problems associated with<br />

social and economic growth <strong>in</strong> your country,<br />

I assure you that <strong>the</strong> Church is one with you<br />

<strong>in</strong> your long<strong>in</strong>g to preserve your unique<br />

cultures and <strong>in</strong> your desire to participate <strong>in</strong><br />

decisions which affect your lives and <strong>the</strong> lives<br />

of your children (John Paul II, 1990, #52).<br />

The church’s commitment to uphold <strong>the</strong> dignity,<br />

identity, and culture of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous peoples is<br />

reiterated by <strong>the</strong> Catholic Bishops Conferences of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Philipp<strong>in</strong>es. Moreover, <strong>the</strong> consultation on<br />

“Indigenous /Tribal Peoples <strong>in</strong> Asia and Challenges<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Future” (Pattaya, Thailand, 2001), organized<br />

by <strong>the</strong> Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences<br />

(FABC) expressed its concern for <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous<br />

peoples <strong>in</strong> Asia when it stated:<br />

The church’s task <strong>in</strong>cludes help<strong>in</strong>g people to<br />

express and preserve <strong>the</strong>ir identity <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> face<br />

of modernization, urbanization and<br />

exploitation, and to keep alive and promote<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir cultural traditions. The church must<br />

undertake a dialogue with <strong>the</strong> followers of<br />

traditional religions <strong>in</strong> order to reaffirm <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

positive human and div<strong>in</strong>e values expressed<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>m and to lay sound bases for<br />

cooperation and solidarity with <strong>the</strong> followers<br />

of traditional religions. At <strong>the</strong> same time, <strong>the</strong><br />

church must defend <strong>the</strong> rights of <strong>in</strong>digenous/<br />

tribal people to become Christ’s disciples<br />

without be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>reby cut off from <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

ancestral roots (Eilers, 2002, p. 227).<br />

Remarkably, <strong>the</strong> church affirms <strong>the</strong><br />

understand<strong>in</strong>g that becom<strong>in</strong>g a Christian does not<br />

mean alienation from one’s ancestral roots and<br />

<strong>in</strong>digenous identity. Indeed, Christianity could help<br />

enhance <strong>the</strong> life-promot<strong>in</strong>g aspects of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>digenous tradition. Such understand<strong>in</strong>g can also<br />

help clarify some of <strong>the</strong> problems encountered by<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> Christians who, because of ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>digenous cultural heritage, has been accused<br />

of “mix<strong>in</strong>g paganism with Christianity” or<br />

“paganiz<strong>in</strong>g Christianity.” For <strong>the</strong>m, it is a matter<br />

of liv<strong>in</strong>g out <strong>the</strong>ir existence <strong>in</strong> two traditions at once<br />

(Starkloff, 2007, p. 290).<br />

As such, I propose that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> religious<br />

tradition/experience serve as <strong>the</strong> start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t/<br />

matrix from which a dialogue may be forged. It is<br />

assumed that a Christian dialogical stance provides<br />

an opportunity for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> and Christian<br />

traditions to <strong>in</strong>form and transform each o<strong>the</strong>r and<br />

mutually deepen each o<strong>the</strong>r’s spirituality through<br />

co-existence, co-operation, respect for<br />

differences, harmony, and partnership especially<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> task of promot<strong>in</strong>g and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> life<br />

and well-be<strong>in</strong>g of peoples <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir particular cultural<br />

and historical milieu.<br />

THE BENGUET EXPERIENCE<br />

Sett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Scene<br />

The prov<strong>in</strong>ce of <strong>Benguet</strong> is located at <strong>the</strong><br />

sou<strong>the</strong>rn tip of <strong>the</strong> Cordillera Adm<strong>in</strong>istrative<br />

Region. Bounded on <strong>the</strong> north by Ilocos Sur and<br />

Mounta<strong>in</strong> Prov<strong>in</strong>ce, on <strong>the</strong> east by Ifugao and<br />

Nueva Vizcaya, on <strong>the</strong> south by Pangas<strong>in</strong>an, and<br />

on <strong>the</strong> west by La Union. <strong>Benguet</strong> serves as one<br />

of <strong>the</strong> gateways to <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> Cordillera<br />

prov<strong>in</strong>ces of Mounta<strong>in</strong> Prov<strong>in</strong>ce, Ifugao, Abra,<br />

Kal<strong>in</strong>ga, and Apayao. The peoples of <strong>the</strong><br />

Cordillera share <strong>the</strong> collective identity of be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

called Igorots or mounta<strong>in</strong> dwellers.<br />

<strong>Benguet</strong> consists of thirteen municipalities and<br />

<strong>the</strong> chartered city of Baguio. Its prov<strong>in</strong>cial capital<br />

is La Tr<strong>in</strong>idad. It is <strong>the</strong> home of two major ethnol<strong>in</strong>guistic<br />

groups, <strong>the</strong> Kankanaeys and <strong>the</strong> Ibalois.<br />

In addition to <strong>the</strong>se two major groups are smaller<br />

ethno-l<strong>in</strong>guistic groups that <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>the</strong> Karao, <strong>the</strong>

UNDERSTANDING ANCESTOR REVERENCE IN THE BENGUET TRADITION<br />

TARAY, L.L. 65<br />

Ikalahan, and <strong>the</strong> Kalanguya communities.<br />

Generally speak<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong> Kankanaeys and <strong>the</strong><br />

Ibalois share <strong>the</strong> same beliefs and practices<br />

(Prov<strong>in</strong>cal Government, 2005, p. 20). Accord<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to Was<strong>in</strong>g Sacla and o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Benguet</strong> observers,<br />

<strong>the</strong>se two major groups share a common belief<br />

system; <strong>the</strong> difference lies <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> language used <strong>in</strong><br />

articulat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se beliefs (1987, p. 4).<br />

<strong>Benguet</strong> is blessed with a cool climate and p<strong>in</strong>e<br />

trees but more importantly it is endowed with rich<br />

natural and m<strong>in</strong>eral resources. Such resources<br />

attracted colonial and postcolonial governments to<br />

<strong>the</strong> mounta<strong>in</strong>s and rivers of <strong>Benguet</strong> at <strong>the</strong> expense<br />

of <strong>the</strong> local people, <strong>the</strong>ir lands, and <strong>the</strong>ir cultural life.<br />

As part of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> culture/tradition, I was<br />

made to deeply feel marg<strong>in</strong>alized for be<strong>in</strong>g an<br />

Igorot or a mounta<strong>in</strong> dweller. My early years were<br />

spent <strong>in</strong> an American-owned sawmill and logg<strong>in</strong>g<br />

area <strong>in</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> where <strong>the</strong> majority of <strong>the</strong><br />

employees were lowlanders. Most of <strong>the</strong> Igorot<br />

laborers were stationed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mounta<strong>in</strong>s where <strong>the</strong>y<br />

worked under <strong>the</strong> sun and ra<strong>in</strong> with only a small<br />

shack to run to for protection. Every two weeks,<br />

it was commonplace to see <strong>the</strong>se people com<strong>in</strong>g<br />

down from <strong>the</strong> mounta<strong>in</strong>s to claim <strong>the</strong>ir hard-earned<br />

wages and to buy <strong>the</strong>ir provisions to keep <strong>the</strong>m<br />

go<strong>in</strong>g till <strong>the</strong> next payday. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>y were not<br />

provided liv<strong>in</strong>g quarters with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> company<br />

compound, some of <strong>the</strong>m stayed with our family<br />

for a day or two to rest or to meet a family member<br />

before head<strong>in</strong>g back to work. With <strong>the</strong>ir provisions<br />

on <strong>the</strong>ir backs, <strong>the</strong>y hiked 5-6 hours before<br />

reach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir mounta<strong>in</strong> abode.<br />

Meanwhile, <strong>the</strong> lowland employees worked <strong>in</strong><br />

offices with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> company premises, lived with<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir families <strong>in</strong> bunkhouses or cottages equipped<br />

with radios and TV sets, and enjoyed recreational<br />

and sports facilities, as well as access to health<br />

care. In terms of job promotion, very few Igorots<br />

were able to go up <strong>the</strong> ladder. In school, my fellow<br />

Igorot pupils and I had been constantly on <strong>the</strong><br />

receiv<strong>in</strong>g end of pejorative remarks and soon<br />

became <strong>the</strong> underdog <strong>in</strong> school activities. This led<br />

many to take a combative stance to defend<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves aga<strong>in</strong>st non-Igorots as well as to excel<br />

<strong>in</strong> academic pursuits.<br />

To add to <strong>the</strong> marg<strong>in</strong>alization of <strong>the</strong> Igorot<br />

laborers, <strong>the</strong> local communities liv<strong>in</strong>g around <strong>the</strong><br />

company area were treated as “outsiders” and<br />

were rarely allowed to enter <strong>the</strong> premises except<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g special events like Christmas and New Year<br />

or when <strong>the</strong>y were <strong>in</strong> need of immediate medical<br />

attention. Years before, <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors were<br />

pushed to <strong>the</strong> periphery when <strong>the</strong> foreign company<br />

took over <strong>the</strong> area. They were often treated with<br />

suspicion whenever <strong>the</strong>y were <strong>in</strong>side <strong>the</strong> compound.<br />

I saw <strong>the</strong> same situation <strong>in</strong> Ambuklao Dam (also<br />

located <strong>in</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong>). Ibaloi families lost <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

ancestral lands and community life to give way to<br />

<strong>the</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> dam <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1950s. The promises<br />

of relocation and employment by <strong>the</strong> national<br />

government that took <strong>the</strong>ir lands never materialized.<br />

In fact, most of <strong>the</strong> employees of <strong>the</strong> dam were<br />

lowlanders. To make matters worse, <strong>the</strong><br />

communities liv<strong>in</strong>g around <strong>the</strong> dam got <strong>the</strong>ir own<br />

share of electricity only <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1990s.<br />

The experiences mentioned above are but a few<br />

examples of <strong>the</strong> marg<strong>in</strong>alization of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong><br />

Igorots. The dist<strong>in</strong>ction between lowland Filip<strong>in</strong>os<br />

(“more civilized, ref<strong>in</strong>ed, and Christian”) and<br />

highland Filip<strong>in</strong>os (“ignorant, dirty, and Igorot”)<br />

resulted <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> unjust treatment of <strong>the</strong> Igorots. Some<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Igorot workers accepted <strong>the</strong>ir lot as a fact<br />

of life. They looked at <strong>the</strong>mselves simply as <strong>in</strong>ferior<br />

mounta<strong>in</strong> peoples. However, many of <strong>the</strong>m were<br />

frustrated and dissatisfied with <strong>the</strong> way th<strong>in</strong>gs were<br />

but were unable to articulate <strong>the</strong>ir sentiments for<br />

fear of be<strong>in</strong>g dismissed from <strong>the</strong> job or becom<strong>in</strong>g<br />

a “lonely voice from <strong>the</strong> mounta<strong>in</strong>s.” Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore,<br />

<strong>the</strong> pejorative connotation of be<strong>in</strong>g an Igorot<br />

brought embarrassment, denial, and an identity<br />

crisis for some. A colonial mentality, a recognition<br />

of colonial mastery and power was very much <strong>in</strong><br />

evidence when I recall <strong>the</strong> deference and childlike<br />

admiration <strong>the</strong> Filip<strong>in</strong>os had towards <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

foreign employers.<br />

I attended a Catholic high school where most<br />

of <strong>the</strong> students were Kankanaeys and Ibalois. Just<br />

as I was beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g to feel at home with my Igorot<br />

identity I found myself struggl<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>the</strong> conflict<br />

between my Christian religion and <strong>the</strong> religion and<br />

tradition of my ancestors. Despite <strong>the</strong> fact that I

66 ASIA-PACIFIC SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW<br />

VOL. 8 NO. 1<br />

am one of <strong>the</strong> grandchildren of a local mambunong<br />

(<strong>in</strong>digenous healer; babaylan or manggagamot,<br />

as <strong>the</strong>y are called <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r regions; or shaman <strong>in</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r Asiatic and some European cultures) and<br />

surrounded by a lot of relatives who were<br />

traditional practitioners, I sometimes felt alienated<br />

from my own tradition. This alienation deepened<br />

when our religion teacher, a Filip<strong>in</strong>o nun who was<br />

also <strong>the</strong> school pr<strong>in</strong>cipal, told us that believ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

Kabunian as a god was idolatrous, believ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

spirits was superstitious, spirit-possession was<br />

ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> work of <strong>the</strong> demon or a manifestation of<br />

personality deviation, our ancestors needed our<br />

prayers to get <strong>the</strong>m out of <strong>the</strong> pagan darkness and<br />

get <strong>the</strong>m to heaven, and that native rituals were<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>gless and useless ways of spend<strong>in</strong>g one’s<br />

resources. Such strong remarks elicited mixed<br />

reactions from <strong>the</strong> class. These remarks made me<br />

even more critical of <strong>the</strong> religion of my people.<br />

In my hometown (Kapangan), <strong>the</strong>re had been<br />

some heated disagreement between some<br />

Christians and traditional practitioners particularly<br />

<strong>in</strong> with regard to ritual performance. The converts<br />

were accused of hav<strong>in</strong>g turned away from <strong>the</strong><br />

traditions of <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors. To some extent, that<br />

was true (especially those who converted to<br />

evangelical Christianity) but <strong>the</strong> greater majority<br />

chose to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir beliefs and practices.<br />

Gabriel Pawid Keith observes that <strong>Benguet</strong><br />

Christians perform simple or elaborate rituals to<br />

remember <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors; <strong>the</strong>y go to church, yet<br />

call on <strong>the</strong> mambunong to propitiate <strong>the</strong> spirits<br />

and ancestors; <strong>the</strong>y consult <strong>the</strong> doctor and take<br />

<strong>the</strong> prescribed medic<strong>in</strong>e yet call on <strong>the</strong><br />

mambunong to perform <strong>the</strong> heal<strong>in</strong>g ritual for <strong>the</strong>m;<br />

and when faced with a series of misfortunes or<br />

losses, <strong>the</strong>y turn to <strong>the</strong>ir deities and ancestors.<br />

Where <strong>the</strong> imported ways do not seem effective,<br />

<strong>the</strong> tradition becomes <strong>the</strong> last resort (Keith, 1987,<br />

p. 16).<br />

Eufronio Pungayan and Isikias Picpican likewise<br />

note that <strong>Benguet</strong> Christians are syncretistic, i.e.,<br />

practic<strong>in</strong>g a conflated version of <strong>the</strong>ir native religion<br />

and <strong>the</strong>ir new religion (Pungayan and Picpican,<br />

1978, p. 463). <strong>Benguet</strong> Christians and traditional<br />

practitioners have attempted to accommodate both<br />

traditions when celebrat<strong>in</strong>g life or <strong>in</strong> deal<strong>in</strong>g with<br />

critical situations. This could be some sort of<br />

leverage so as to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> spirit of solidarity<br />

with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> community and to keep it from break<strong>in</strong>g<br />

apart, despite disagreements. Unfortunately, <strong>the</strong><br />

lack of commitment from <strong>the</strong> church to really listen<br />

and f<strong>in</strong>d a home <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> local tradition brought<br />

confusion to local Christians. Remarkably, some<br />

of those who rema<strong>in</strong> opposed to <strong>the</strong> native beliefs<br />

and rituals come from <strong>the</strong> ranks of <strong>the</strong> native clergy<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves whose <strong>the</strong>ological tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g reflects a<br />

coloniz<strong>in</strong>g religion.<br />

The struggles of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> Igorot Christians<br />

like myself alerted me to pay attention and<br />

rediscover <strong>the</strong> significance of ancestors amidst <strong>the</strong><br />

contemporary <strong>Benguet</strong> experience. I believe that<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itial step towards a Christian understand<strong>in</strong>g<br />

of ancestor reverence is <strong>in</strong>deed <strong>the</strong> task of culture<br />

bearers like <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> Christians <strong>the</strong>mselves.<br />

This task requires an attentive <strong>in</strong>vestigation and<br />

study of <strong>the</strong>ir own beliefs and practices associated<br />

with <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors. Equipped with first-hand<br />

experience, <strong>in</strong>formation, and understand<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

own traditions, <strong>Benguet</strong> Christians can be effective<br />

dialogue partners <strong>in</strong> explor<strong>in</strong>g some possibilities <strong>in</strong><br />

which <strong>the</strong> two traditions can work toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong><br />

uplift<strong>in</strong>g and promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> life and dignity of a<br />

marg<strong>in</strong>alized people. In this sense, Christianity is<br />

no longer <strong>the</strong> only source of wisdom and agent of<br />

salvation but a partner and fellow sojourner <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

human quest for salvation.<br />

<strong>Ancestor</strong> <strong>Reverence</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong><br />

Religion/<strong>Tradition</strong><br />

This paper does not describe <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong><br />

religion <strong>in</strong> its most prist<strong>in</strong>e state. Obviously, its task<br />

is not to pa<strong>in</strong>t a hypo<strong>the</strong>tical, glow<strong>in</strong>g picture of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous religion of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> past. Stereotyp<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>digenous religions as “static<br />

voices from <strong>the</strong> past” <strong>in</strong>dicates a failure to<br />

acknowledge <strong>the</strong>ir survival potential, that is, <strong>the</strong><br />

dynamism of <strong>the</strong>se cultures/religions which repeatedly<br />

have to adjust to <strong>the</strong> challenges posed by o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

people and <strong>the</strong> changes tak<strong>in</strong>g place <strong>in</strong> human<br />

history (Smith, Burke, and Ward, 2000, p. 6).

UNDERSTANDING ANCESTOR REVERENCE IN THE BENGUET TRADITION<br />

TARAY, L.L. 67<br />

We are deal<strong>in</strong>g with a liv<strong>in</strong>g tradition, a dynamic<br />

religion <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong>re are new areas of application<br />

as well as cont<strong>in</strong>uities with <strong>the</strong> past. The <strong>Benguet</strong><br />

religious rituals and observances often mirror <strong>the</strong><br />

fluid – cultural responses to chang<strong>in</strong>g economic,<br />

social, and political conditions <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong><br />

people f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong>mselves (Russel, 1980, p. 4). The<br />

various transformation processes that occur are,<br />

of course, products of <strong>the</strong> local people and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

history. People cultivate various strategies when<br />

adapt<strong>in</strong>g to new situations and <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people<br />

are certa<strong>in</strong>ly no exception.<br />

A comprehensive and detailed presentation and<br />

analysis of <strong>the</strong> beliefs and practices associated with<br />

ancestor reverence is beyond <strong>the</strong> scope of this<br />

paper. Never<strong>the</strong>less, some key po<strong>in</strong>ts presented<br />

below could provide basic <strong>in</strong>formation.<br />

Beliefs<br />

Belief <strong>in</strong> Sacred Be<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

The <strong>Benguet</strong> people believe <strong>in</strong> a community of<br />

sacred be<strong>in</strong>gs with Kabunian as <strong>the</strong> creator and<br />

prime mover of everyth<strong>in</strong>g that exists. Included <strong>in</strong><br />

this sacred community are <strong>the</strong> gods and goddesses,<br />

nature deities like <strong>the</strong> sun, moon, star and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

heavenly bodies, spirits dwell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> nature, and<br />

ancestors who are now <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ancestral abode.<br />

Kabunian, <strong>the</strong> gods and goddesses are perceived<br />

to have lived on earth, gotten married, and have<br />

borne children. While on earth, <strong>the</strong>y performed<br />

rituals and taught people how to live and to observe<br />

<strong>the</strong> traditions. After death, <strong>the</strong>y went to live <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

sky world but <strong>the</strong>ir relationship with <strong>the</strong> human<br />

world goes on. In <strong>the</strong> account titled Kabunian (see<br />

Mallari, 1953, p. 65), Kabunian is said to have<br />

lived <strong>in</strong> Mt. Pulog (found <strong>in</strong> Kabayan, <strong>Benguet</strong> and<br />

second highest mounta<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Philipp<strong>in</strong>es) with<br />

his beautiful wife Bugan. He protected his people<br />

from sickness and fam<strong>in</strong>e. He even cooked rice<br />

for a family who had noth<strong>in</strong>g to eat and henceforth,<br />

<strong>the</strong> family never went hungry aga<strong>in</strong>. The story goes<br />

on to say that when Kabunian and his wife died,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y went to <strong>the</strong> sky world and <strong>the</strong> people started<br />

perform<strong>in</strong>g rituals to remember <strong>the</strong>ir good examples<br />

and to thank <strong>the</strong>m for <strong>the</strong>ir generosity and<br />

k<strong>in</strong>dness. Such a story speaks of a people’s belief<br />

<strong>in</strong> a deity who partook of <strong>the</strong> joys and difficulties<br />

of <strong>the</strong> human condition and who acted with<br />

compassion.<br />

Part of <strong>the</strong> sacred community are <strong>the</strong> Ap-apo,<br />

Ka-apuan, Eyon-a or ammed, men and women<br />

who died generations ago and are now <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

ancestral abode with Kabunian and o<strong>the</strong>r deities.<br />

In <strong>the</strong>ir earthly lives <strong>the</strong> ammed/ka-apuan may<br />

have produced offer<strong>in</strong>gs and celebrated kanyaw<br />

(rituals) for <strong>the</strong> spirits of those who had gone before<br />

<strong>the</strong>m. Some of <strong>the</strong>m may have been <strong>in</strong>fluential<br />

members of <strong>the</strong>ir communities. Now, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

afterlife, <strong>the</strong>y are bestowed <strong>the</strong> rank and respect<br />

that befit <strong>the</strong>ir actions when <strong>the</strong>y were men and<br />

women of this earth. Some were great warriors<br />

who outlived <strong>the</strong>ir adversaries and now share <strong>the</strong><br />

status of godhood. Some acquired <strong>the</strong>ir prestige<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> afterlife because of <strong>the</strong> rituals performed <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir honor. <strong>Ancestor</strong>s rema<strong>in</strong> members of <strong>the</strong><br />

family or clan and <strong>the</strong>ir sacred status bestow on<br />

<strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong> power to grant bless<strong>in</strong>gs of prosperity,<br />

health, fecundity, and long life to <strong>the</strong>ir descendants.<br />

When <strong>the</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g relatives remember <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are helped <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> fulfillment of <strong>the</strong>ir needs, but<br />

if <strong>the</strong> ancestors are forgotten or neglected, it is<br />

also with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir power to cause illness or<br />

misfortune to <strong>the</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g (Mer<strong>in</strong>o, 1987, pp. 13-<br />

14). For <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people, <strong>the</strong>ir mode of action<br />

is rooted <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>eage, consangu<strong>in</strong>ity and aff<strong>in</strong>ity. The<br />

dynamic relationship between ancestors and <strong>the</strong><br />

liv<strong>in</strong>g is fur<strong>the</strong>r discussed below.<br />

Belief <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> dynamism of <strong>the</strong> spirit-human<br />

worlds<br />

The belief <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> dynamism of <strong>the</strong> spirit-human<br />

world has always been one of <strong>the</strong> basic sacred<br />

postulates of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous religion.<br />

Somehow <strong>the</strong>re is both a cont<strong>in</strong>uity and<br />

discont<strong>in</strong>uity between this life and <strong>the</strong> next. The<br />

<strong>Benguet</strong> people believe that <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors, while<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are now <strong>in</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r realm of existence, ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir appetite for th<strong>in</strong>gs that were familiar to <strong>the</strong>m<br />

<strong>in</strong> life (communal ga<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>gs, food, tapey or rice<br />

w<strong>in</strong>e, blankets, clo<strong>the</strong>s, etc.). Moreover, it is<br />

perceived that <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors brought with <strong>the</strong>m

68 ASIA-PACIFIC SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW<br />

VOL. 8 NO. 1<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir socio-economic status and <strong>the</strong>ir occupation<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> spirit world where <strong>the</strong>y cont<strong>in</strong>ue work<strong>in</strong>g<br />

for <strong>the</strong>ir descendants on earth. For <strong>the</strong> satisfaction<br />

of <strong>the</strong>ir needs and <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>tenance of <strong>the</strong>ir status,<br />

<strong>the</strong> ancestors are quite dependent on <strong>the</strong> ritual<br />

performances of liv<strong>in</strong>g relatives. When <strong>in</strong> need,<br />

certa<strong>in</strong> recurr<strong>in</strong>g events, dreams or o<strong>the</strong>r means<br />

like “spirit-possession” are considered valid ways<br />

by which <strong>the</strong> dead communicate <strong>the</strong>ir wishes to<br />

<strong>the</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g. Experiences such as <strong>the</strong>se are not to<br />

be ignored.<br />

The dynamism between <strong>the</strong> spirit and human<br />

worlds is not limited to <strong>the</strong> ancestor-descendant<br />

relationship. An important feature of <strong>the</strong>ir society<br />

is that <strong>the</strong>y make no dist<strong>in</strong>ctions between <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

social world and <strong>the</strong>ir natural environment. The sky<br />

world, <strong>the</strong> earth world, and <strong>the</strong> underworld make<br />

up <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people’s religious universe. The<br />

people see <strong>the</strong>ir world as a dwell<strong>in</strong>g place for<br />

humans and spirits. Depart<strong>in</strong>g from an anthropocentric<br />

view of <strong>the</strong> world, humanity is seen as<br />

part of <strong>the</strong> bigger community of deities, ancestors,<br />

spirits, and nature. This view is recognized by<br />

Claerhoudt who observed <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people as<br />

constantly <strong>in</strong>teract<strong>in</strong>g with Kabunian and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

nature deities (e.g., Agew or Sun, Buwan or<br />

Moon, Balikongkong or a constellation), with <strong>the</strong><br />

spirits dwell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> all sorts of places, <strong>the</strong><br />

tommongaw or malevolent spirits, with <strong>the</strong> p<strong>in</strong>ad<strong>in</strong>g<br />

or benevolent spirits, <strong>the</strong> p<strong>in</strong>ten or <strong>the</strong> souls<br />

who cannot enter <strong>the</strong> ancestral abode, and<br />

especially with <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors who live <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> holy<br />

Pulog mounta<strong>in</strong> (Claerhoudt, 1967, p. 77). It is<br />

thus important for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><br />

peace and harmony with both <strong>the</strong> visible and<br />

<strong>in</strong>visible be<strong>in</strong>gs. Places believed to be <strong>the</strong> abode<br />

of spirits must be respected and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed. In<br />

return <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people expect <strong>the</strong> unseen world<br />

to be k<strong>in</strong>d to <strong>the</strong>m as well. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Benguet</strong> people recognize <strong>the</strong>ir connectedness and<br />

dependence on <strong>the</strong> sky world and heavenly bodies<br />

and affirm such relationship through rituals. Hav<strong>in</strong>g<br />

said this, we may describe <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> religion as<br />

a bio-cosmic religion s<strong>in</strong>ce it recognizes <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>terconnectedness and <strong>in</strong>terdependence of all<br />

be<strong>in</strong>gs. Such connectivity also <strong>in</strong>cludes <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong><br />

people’s recognition of <strong>the</strong>ir cont<strong>in</strong>uity with <strong>the</strong> past<br />

and with <strong>the</strong> future.<br />

Hope <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> fullness of life as “here-and-now”<br />

and as a future event<br />

The <strong>Benguet</strong> people’s aspirations for a fuller life<br />

or for well-be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> this life and <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> next have no<br />

systematic and coherent textual articulation. In fact,<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir hopes and dreams are often articulated <strong>in</strong><br />

almost all <strong>the</strong>ir rituals. For example, <strong>the</strong> ritual meal,<br />

which is always a part of <strong>the</strong>ir rituals, does not<br />

simply mirror <strong>the</strong>ir aspirations for solidarity,<br />

abundance and shar<strong>in</strong>g, but <strong>the</strong>y are actually liv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

out and experienc<strong>in</strong>g such aspirations <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> hereand-now.<br />

When <strong>the</strong>y come toge<strong>the</strong>r to relax, to<br />

tell stories, and to share a meal with <strong>the</strong> spirit-human<br />

worlds, <strong>the</strong>y are liv<strong>in</strong>g out <strong>the</strong>ir vision of communal<br />

solidarity where people let go of <strong>the</strong>ir personal<br />

concerns <strong>in</strong> order to celebrate life and streng<strong>the</strong>n<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir relationships. Social solidarity has always<br />

been primary among <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people.<br />

In <strong>the</strong>ir ritual performances, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people<br />

often articulate <strong>the</strong>ir aspirations for wealth, health,<br />

long life, fecundity, unity, peace and stability <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

village. These are all bless<strong>in</strong>gs from Kabunian, <strong>the</strong><br />

deities and ancestors. Their rituals are tools for<br />

enhanc<strong>in</strong>g life <strong>in</strong> its broad sense and hence, ritual<br />

performance is an <strong>in</strong>dispensable means <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

atta<strong>in</strong>ment of <strong>the</strong>ir dreams. Equally important is <strong>the</strong><br />

belief that such bless<strong>in</strong>gs can only be granted with<br />

human cooperation and work. Work is understood<br />

as a participative action of <strong>the</strong> spirit-human worlds<br />

<strong>in</strong> order to br<strong>in</strong>g such bless<strong>in</strong>gs to this life and to<br />

<strong>the</strong> next. The fruits of one’s labor are not only for<br />

personal satisfaction but also for <strong>the</strong> enjoyment of<br />

<strong>the</strong> community. Such shar<strong>in</strong>g of bless<strong>in</strong>g is<br />

actualized <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ritual meal where <strong>the</strong> community<br />

of visible and <strong>in</strong>visible be<strong>in</strong>gs come toge<strong>the</strong>r to<br />

nourish <strong>the</strong>mselves. Generosity/benevolence is part<br />

of <strong>the</strong>ir ethical life. They believe that <strong>the</strong> more a<br />

person shares her/his bless<strong>in</strong>gs to <strong>the</strong> community<br />

of <strong>the</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>the</strong> dead, <strong>the</strong> more bless<strong>in</strong>gs will<br />

come <strong>in</strong>to her/his household and to <strong>the</strong> community.<br />

S<strong>in</strong>ce life is closely identified with <strong>the</strong> land, it is<br />

also <strong>the</strong>ir hope to preserve <strong>the</strong> life and unity of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir illi (village). Their dream to live <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir village

UNDERSTANDING ANCESTOR REVERENCE IN THE BENGUET TRADITION<br />

TARAY, L.L. 69<br />

until <strong>the</strong>y are old and bent is often expressed <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir prayers. In death, <strong>the</strong>y would like to be buried<br />

with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own land. It is <strong>the</strong>refore not surpris<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to see many <strong>Benguet</strong> homes hav<strong>in</strong>g a tomb or two<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> family yard. Indeed, land is a legacy from<br />

those who lived before <strong>the</strong>m and <strong>the</strong>ir rice fields<br />

are monuments of <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors’ sheer<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>ation to survive. Likewise, it is <strong>the</strong>ir fervent<br />

hope not to be neglected nor despised<br />

(maamamaengan) for who and what <strong>the</strong>y are.<br />

In addition to <strong>the</strong>ir aspirations for <strong>the</strong> here-andnow,<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people hope to be an ancestor<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> afterlife. Such aspiration can be realized if<br />

one lives an ethical life (a good example to <strong>the</strong> family<br />

and community, ritual observance, etc.). They<br />

believe that <strong>the</strong> more one is remembered by <strong>the</strong><br />

liv<strong>in</strong>g through ritual performance, <strong>the</strong> better is one’s<br />

chance of acceptance <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ancestral abode. It is<br />

<strong>the</strong>n an obligation of family members to perform<br />

<strong>the</strong> appropriate ritual <strong>in</strong> order to help <strong>the</strong>ir dead<br />

atta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> status of godhood <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> afterlife.<br />

The sacred postulates mentioned above are not<br />

simply ideas or concepts to be accepted. The<br />

<strong>Benguet</strong> people’s <strong>in</strong>terpretation of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

experiences of joy, grief, success, failure, etc. are<br />

colored by <strong>the</strong>ir cosmological understand<strong>in</strong>gs.<br />

Perhaps, we can understand better <strong>the</strong>se beliefs<br />

by look<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to some of <strong>the</strong>ir rituals.<br />

Ritual Practices<br />

Undoubtedly, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people love ritual<br />

performances. Ritual practices and cosmological<br />

understand<strong>in</strong>gs cannot be separated from <strong>the</strong>ir daily<br />

rounds of subsistence practices. This rem<strong>in</strong>ds us<br />

once aga<strong>in</strong> that analysis of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> beliefs and<br />

practices <strong>in</strong>cludes subsistence, k<strong>in</strong>ship, and<br />

<strong>in</strong>timacy with <strong>the</strong> landscape and language.<br />

A general observation on why <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong><br />

people love rituals is <strong>the</strong> fact that through <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

rituals <strong>the</strong>ir collective beliefs and ideals are<br />

experienced, affirmed, and articulated <strong>in</strong> a much<br />

deeper and more mean<strong>in</strong>gful way than <strong>in</strong> creedal<br />

or doctr<strong>in</strong>al formulations. Notably, much of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Benguet</strong> rituals are those that are performed <strong>in</strong><br />

honor of <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors.<br />

Ritual as w<strong>in</strong>dow <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> heart<br />

of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people’s social life<br />

The persistence of ritual performance honor<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir ancestors shows <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> belief that<br />

ancestors play a major role <strong>in</strong> fortify<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir solidarity as a k<strong>in</strong> group and<br />

as an <strong>in</strong>digenous community. Dur<strong>in</strong>g ritual<br />

performance people are expected to let go of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>dividual preoccupations <strong>in</strong> order to jo<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> community <strong>in</strong> honor<strong>in</strong>g, remember<strong>in</strong>g and<br />

reconnect<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors. It is always<br />

important for <strong>the</strong> mambunong and <strong>the</strong> family<br />

host<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> ritual to mention <strong>the</strong> name of <strong>the</strong><br />

ancestor for whom <strong>the</strong> ritual is be<strong>in</strong>g performed<br />

and to <strong>in</strong>vite <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r ancestors as well. This is<br />

a way of remember<strong>in</strong>g and giv<strong>in</strong>g recognition to<br />

each of <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors. Hence, rituals are sacred<br />

moments when <strong>the</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>the</strong> dead come<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r to streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>ir solidarity and<br />

<strong>in</strong>terdependence. Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> performance, <strong>the</strong><br />

family yard becomes <strong>the</strong> sacred space where<br />

<strong>the</strong> human-spirit worlds come toge<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

Ritual as affirmation of mutuality between<br />

<strong>the</strong> spirit-human worlds<br />

<strong>Benguet</strong> spirituality 1 <strong>in</strong>volves mutual giv<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

receiv<strong>in</strong>g, enjoyment, forgiveness, and<br />

remembrance. For example, when it is determ<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

by <strong>the</strong> elders and experts of tradition that <strong>the</strong>re<br />

are <strong>in</strong>deed conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g signs that an ancestor wishes<br />

to shower bless<strong>in</strong>gs on her/his liv<strong>in</strong>g relatives, <strong>the</strong><br />

agamid and sangbo rituals are performed as ways<br />

of recogniz<strong>in</strong>g and reciprocat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> benevolence<br />

of <strong>the</strong> ancestor.<br />

A reciprocal relationship is equally important<br />

among <strong>the</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g members of <strong>the</strong> community. For<br />

<strong>in</strong>stance, <strong>the</strong> giv<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> upo is a form of economic<br />

and social obligation to be observed <strong>in</strong> times of<br />

death. Death does not only br<strong>in</strong>g loss to <strong>the</strong><br />

family but also to <strong>the</strong> whole community. In<br />

<strong>Benguet</strong>, relatives and <strong>the</strong> community are<br />

obliged to give material support <strong>in</strong> cash or <strong>in</strong><br />

k<strong>in</strong>d (rice, coffee, bread, dr<strong>in</strong>ks, firewood, etc.)<br />

to <strong>the</strong> bereaved family. Significantly, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong><br />

people believe that <strong>the</strong> dead would acknowledge<br />

and take <strong>the</strong>se items as baon (packed meal or

70 ASIA-PACIFIC SOCIAL SCIENCE REVIEW<br />

VOL. 8 NO. 1<br />

resources) and pasalubong (homecom<strong>in</strong>g<br />

presents; gifts) to <strong>the</strong> ancestral abode. In<br />

addition, relatives and neighbors of <strong>the</strong> bereaved<br />

do <strong>the</strong> cook<strong>in</strong>g, serv<strong>in</strong>g, and keep<strong>in</strong>g of th<strong>in</strong>gs<br />

<strong>in</strong> order so that <strong>the</strong> bereaved family can focus<br />

on <strong>the</strong> rituals. The bereaved family, <strong>in</strong> turn, is<br />

expected to reciprocate when o<strong>the</strong>rs are also<br />

faced with <strong>the</strong> same situation. Reciprocity or<br />

mutuality, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people’s “Golden Rule,”<br />

rema<strong>in</strong>s operative <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir community life.<br />

Ritual as a drama of collective sentiments<br />

and a public space for a marg<strong>in</strong>alized people<br />

Through <strong>the</strong>ir ritual performance, <strong>the</strong> spirit of<br />

solidarity and mutuality <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> community is<br />

enhanced and affirmed. Significantly, it is also<br />

through <strong>the</strong>ir rituals that <strong>the</strong>y attempt to redress<br />

<strong>the</strong> deprivation <strong>in</strong>herent <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir social<br />

peripherality. The constant threat of becom<strong>in</strong>g<br />

once aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> “sacrificial victims before <strong>the</strong><br />

altar of progress and development” has been<br />

plagu<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people. Their sociocultural,<br />

economic, and political marg<strong>in</strong>alization<br />

lead <strong>the</strong>m to turn to <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors as <strong>the</strong> major<br />

source of unity <strong>in</strong> combat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> possible<br />

encroachments of <strong>the</strong>ir lands and properties.<br />

Dur<strong>in</strong>g rituals, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> people br<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

hopes, <strong>the</strong>ir cares and fears to <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors<br />

and deities with <strong>the</strong> understand<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong><br />

ancestors are always <strong>the</strong>re to hear <strong>the</strong>ir plea.<br />

To a great extent, <strong>the</strong>ir rituals express <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

powerlessness and dependence on <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

ancestors and deities. In Kapangan, <strong>the</strong><br />

pamakan (ritual to celebrate <strong>the</strong> memory of <strong>the</strong><br />

local soldiers and guerilla members who died<br />

fight<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Japanese forces dur<strong>in</strong>g World War<br />

II) serves as a challenge to <strong>the</strong> people to protect<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir community and way of life. In this sense,<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir rituals can be a political event, a hallmark<br />

<strong>in</strong> enhanc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> participants’ political<br />

consciousness that alerts <strong>the</strong>m to be more critical<br />

of <strong>the</strong> new model of life and success endorsed<br />

by <strong>the</strong> media or by some government agencies.<br />

Today, <strong>in</strong>dividualism, power, ambition, and<br />

competition are new forms of threat that are seep<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> way of life.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

For <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> Christians and traditionalists<br />

alike, ancestor reverence is here to stay. <strong>Ancestor</strong>s<br />

are deeply <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> life and aspirations of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> soul. <strong>Ancestor</strong>s served as <strong>the</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g<br />

blocks of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> identity and society as we<br />

know <strong>the</strong>se today. They play a key role <strong>in</strong> 1)<br />

fortify<strong>in</strong>g and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir spirit of solidarity<br />

and cooperation as a collective group, 2) mediat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> bless<strong>in</strong>gs (prosperity, health, long life, fertility,<br />

peace, harmony, etc.) needed to live a dignified<br />

life, 3) and susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>m a sense of hope <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> face of uncerta<strong>in</strong>ties. Moreover, <strong>the</strong>y believe<br />

that <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors br<strong>in</strong>g all <strong>the</strong>ir concerns to <strong>the</strong><br />

bigger community of sacred be<strong>in</strong>gs and conv<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

<strong>the</strong>m to act on <strong>the</strong>se needs. Hence we can claim<br />

that ancestors serve as <strong>the</strong> key symbol of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Benguet</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous religion. The ordered world of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir community life is often associated with<br />

ancestor spirits where everyone and everyth<strong>in</strong>g has<br />

a def<strong>in</strong>ed place and function. Their rituals provide<br />

a means by which power from <strong>the</strong> sacred may be<br />

obta<strong>in</strong>ed and practically transform or somehow<br />

affect <strong>the</strong>ir social, economic, and political situation.<br />

Their experience of peripherality has deeply<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluenced <strong>the</strong>ir vision of life (family and community<br />

cohesion, health, long life, abundance, stability,<br />

peace, harmony, etc.). The <strong>Benguet</strong> people believe<br />

that despite <strong>the</strong> contradictions of <strong>the</strong>ir collective<br />

experience, <strong>the</strong>y have survived as <strong>in</strong>dividuals and<br />

as a people. Their tenacity to survive is an<br />

<strong>in</strong>dication of <strong>the</strong>ir beliefs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> abid<strong>in</strong>g presence<br />

and sustenance of <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors.<br />

This <strong>in</strong>vestigation of <strong>the</strong> significance of ancestor<br />

reverence <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous tradition could<br />

help dispel <strong>the</strong> darkness of ignorance that has led<br />

to a lot of misunderstand<strong>in</strong>gs about <strong>the</strong> beliefs and<br />

practices of a people. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, an <strong>in</strong>-depth<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigation can provide outsiders <strong>the</strong> opportunity<br />

to look <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>se beliefs and practices as<br />

understood and lived by <strong>the</strong> people <strong>the</strong>mselves and<br />

to discover <strong>the</strong> significance of <strong>the</strong>ir beliefs and<br />

rituals <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of <strong>the</strong>ir historical experience<br />

as m<strong>in</strong>ority people. Their history is a story of victory<br />

and defeat, <strong>in</strong>dependence and marg<strong>in</strong>alization, and

UNDERSTANDING ANCESTOR REVERENCE IN THE BENGUET TRADITION<br />

TARAY, L.L. 71<br />

of hope and despair. Their struggles and aspirations<br />

are efforts to reclaim <strong>the</strong>ir people’s history and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

recognition as a dist<strong>in</strong>ct community without be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

judged <strong>in</strong>different to national <strong>in</strong>terests. Theirs is a<br />

story of ritual performances and celebrations, of<br />

remembrance, of mutuality, and of ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

harmony with <strong>the</strong> visible and <strong>in</strong>visible worlds.<br />

Hav<strong>in</strong>g this <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d, it is important for non-<strong>in</strong>digenes<br />

to listen and learn how <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous people’s faith<br />

and hopes are experienced and lived and how <strong>the</strong>y<br />

are transformative of peoples (Eilers, 2002, p.<br />

307).<br />

The <strong>Benguet</strong> religion does not have all <strong>the</strong> answers<br />

to <strong>the</strong> present problems and concerns of <strong>the</strong> world<br />

but it can be a source of wisdom and spirituality that<br />

may be relevant to some of <strong>the</strong> press<strong>in</strong>g needs and<br />

challenges of <strong>the</strong> present. In this regard, a dialogical<br />

stance would fortify every <strong>in</strong>ter-religious or <strong>in</strong>tercultural<br />

encounter towards a better appreciation of<br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r; a better show of respect for <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r—<br />

necessary for <strong>the</strong> forg<strong>in</strong>g of friendships and<br />

partnerships; for collaborations that would allow to<br />

br<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> fore <strong>the</strong> wisdom and values of religious<br />

traditions that can <strong>in</strong>spire people to respond to <strong>the</strong><br />

urgent need for justice, peace, harmony, and<br />

susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> human and earth community.<br />

A fur<strong>the</strong>r engagement between <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>digenous tradition and Christianity could lead not<br />

only to a Christian appreciation of ancestor<br />

reverence <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Benguet</strong> tradition but for ancestor<br />

reverence to f<strong>in</strong>d a home <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Christian tradition.<br />

Only <strong>the</strong>n can a Christian dialogical stance allow<br />

<strong>the</strong> flourish<strong>in</strong>g of au<strong>the</strong>ntic traditions of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>digenous peoples. Support for a m<strong>in</strong>ority<br />

population <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir participation <strong>in</strong> vital decisions<br />

presupposes such a stance.<br />

ENDNOTES<br />

1<br />