Roger Paris profile - Funhog Press

Roger Paris profile - Funhog Press

Roger Paris profile - Funhog Press

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

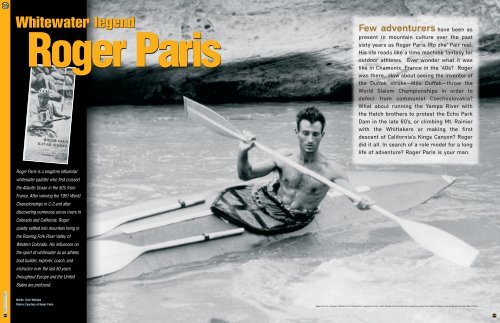

Whitewater legend<br />

<strong>Roger</strong> <strong>Paris</strong><br />

Few adventurers have been as<br />

present in mountain culture over the past<br />

sixty years as <strong>Roger</strong> <strong>Paris</strong> (Ro zhe' Pair ree).<br />

His life reads like a time machine fantasy for<br />

outdoor athletes. Ever wonder what it was<br />

like in Chamonix, France in the ’40s <strong>Roger</strong><br />

was there. How about seeing the inventor of<br />

the Duffek stroke—Milo Duffek—throw the<br />

World Slalom Championships in order to<br />

defect from communist Czechoslovakia<br />

What about running the Yampa River with<br />

the Hatch brothers to protest the Echo Park<br />

Dam in the late 60’s, or climbing Mt. Rainier<br />

with the Whittakers or making the first<br />

descent of California's Kings Canyon <strong>Roger</strong><br />

did it all. In search of a role model for a long<br />

life of adventure <strong>Roger</strong> <strong>Paris</strong> is your man.<br />

<strong>Roger</strong> <strong>Paris</strong> is a longtime influential<br />

whitewater paddler who first crossed<br />

the Atlantic Ocean in the 50’s from<br />

France. After winning the 1951 World<br />

Championships in C-2 and after<br />

discovering numerous unrun rivers in<br />

Colorado and California, <strong>Roger</strong><br />

quietly settled into mountain living in<br />

the Roaring Fork River Valley of<br />

Western Colorado. His influences on<br />

the sport of whitewater as an athlete,<br />

boat builder, explorer, coach, and<br />

instructor over the last 50 years<br />

throughout Europe and the United<br />

States are profound.<br />

PROFILE<br />

Words: Tyler Williams<br />

Photos: Courtesy of <strong>Roger</strong> <strong>Paris</strong><br />

<strong>Roger</strong> <strong>Paris</strong> in a Klepper folboat on the Yampa River, Colorado during a Hatch Brothers/Sierra Club trip to save the canyon from being flooded by the proposed Echo Park Dam (1956).<br />

50<br />

52

PROFILE<br />

"The Nazis are coming!"<br />

This chilling news spread through northern France like<br />

the leading edge of a flash flood, prompting millions to<br />

gather their families and flee. Roads leading south from<br />

<strong>Paris</strong> became endless strings of refugees, moving<br />

incessantly like a column of ants across the bucolic<br />

countryside. Mothers and grandmothers pushed<br />

overflowing carts of their most essential possessions.<br />

Bewildered children marched alongside, their<br />

schoolbook packs loaded with clothes, bread, water—<br />

the basics. Many used wheelbarrows to haul their loads.<br />

Some rode bicycles. A few, the luckiest of the lot, drove<br />

through the slow procession in cars. Eleven year-old<br />

<strong>Roger</strong> <strong>Paris</strong> was one of the lucky ones. He was crammed<br />

in the family car with his brother, sister, parents, and<br />

grandfather.<br />

Time was running out. Bridges were being blown apart<br />

to stop the advance of the German army. Soon the<br />

routes leading to the safer southern farmlands would be<br />

cut-off. <strong>Roger</strong>'s family raced to get across the bridge<br />

before it was too late. As they neared the river, each<br />

rose a little higher in their seats, craning to get a view<br />

of the crossing. The bridge was still there! They rattled<br />

across with a surge of relief as the tension momentarily<br />

eased from the automobile. Moments later, the bridge<br />

was blown. Then the car died. Such was life in France<br />

in June of 1940.<br />

"Luck is part of life," 77-year-old <strong>Roger</strong> <strong>Paris</strong> happily<br />

and wisely says. It is a truth he has carried with him<br />

ever since crossing that bridge in the nick of time. As<br />

the sprightly septuagenarian begins yet another season<br />

of paddling, one gets the feeling that he makes his own<br />

luck. How else can you explain the fact that he is still<br />

adventuring with the same spirit he showed in 1941<br />

when, at age twelve, he took to the rapids under a<br />

broken, bombed-out bridge near his home in Orleans,<br />

France<br />

The <strong>Paris</strong> family returned to their house after three<br />

weeks of hiding in the French countryside only to find it<br />

stripped of household items and ravaged from the<br />

invasion. But as <strong>Roger</strong> says, "Life keeps on going," and<br />

so the wartime routine settled in. <strong>Roger</strong> would<br />

begrudgingly make his way to a strictly run school every<br />

morning, and carefully come home through the battle<br />

debris in the afternoons. He recalls the dark time<br />

pointedly, "Food was scarce, and war dangers were<br />

always around."<br />

When his father came home with a canoe one day,<br />

<strong>Roger</strong>'s dreary existence was infused with a glimmer of<br />

hope. Along with his younger sister and older brother,<br />

<strong>Roger</strong> pushed the open canoe on portage wheels to the<br />

Loire River one mile away, and launched into the<br />

nurturing world of the river.<br />

<strong>Roger</strong> found solace on the Loire. Tucked beneath the<br />

war-torn landscape, the river offered a natural<br />

environment amidst the grim reminders of German<br />

occupation that lurked above the river's banks. The river<br />

was a sanctuary, and as <strong>Roger</strong> says, "It was freedom." A<br />

canal along the river made for easy shuttles, so <strong>Roger</strong><br />

ran the Loire at every opportunity. He picked up<br />

paddling basics on his own, but to maneuver the<br />

bombed bridge rapids with confidence, he needed formal<br />

instruction.<br />

<strong>Roger</strong>'s paddling career truly began to blossom when he<br />

met André Pean. Pean was an athletic former wrestler<br />

who helped instruct young paddlers through the local<br />

canoe club. Like young <strong>Roger</strong>, the middle-aged Pean<br />

found the river a means of escape from the drudgery of<br />

life during world war. The two spent many afternoons<br />

on the Loire, firmly developing a bond through<br />

canoeing. Pean soon took on the role of coach, and<br />

<strong>Roger</strong> was his star athlete.<br />

As <strong>Roger</strong>'s paddling skills developed toward a<br />

<strong>Roger</strong> and Serge Michel in the middle of the first complete descent of the Royal Gorge of the Arkansas River, Colorado (June 1954).<br />

“Once in the rapid<br />

every second was<br />

an emergency…”<br />

recalling his early<br />

descent of the<br />

Royal Gorge.<br />

competitive level, the war came to an end. General<br />

Patton's American troops came marching through <strong>Paris</strong><br />

and its suburbs. War reconstruction began. <strong>Roger</strong>'s<br />

brother André returned from the woods where he'd been<br />

hiding from Nazi conscription. Life began to normalize.<br />

Now an eager teenager, <strong>Roger</strong> followed his older brother<br />

to the Alps after the war. They lingered in the mountain<br />

Mecca of Chamonix, and <strong>Roger</strong> fell in love. He swooned<br />

for the forests, was smitten with the glaciers, hanging<br />

valleys, roaring waterfalls and plummeting ski slopes,<br />

and yearned for every last mountain meadow and craggy<br />

alpine peak. He knew that the mountains would be<br />

where he would spend the rest of his life.<br />

<strong>Roger</strong> met the great climbers Lionel Terray and Louis<br />

Lachenal, and promptly set off to study for his license as<br />

a mountain guide. When <strong>Roger</strong>'s mandatory French<br />

military service called, he naturally entered the ski<br />

troops, and was sent to occupy the Alps of Austria.<br />

After his year in the army, he returned to the city and<br />

tried to re-enter the mainstream by studying economics.<br />

As one might expect, this endeavor was a complete misfit<br />

for <strong>Roger</strong>, and he soon returned to the mountains.<br />

He skied, climbed, and paddled. Among other rivers,<br />

<strong>Roger</strong> ran the Upper Isere, the Upper Arc, and La Rue.<br />

Several were first descents and some were last descents,<br />

as many of the runs are now lost to dams. Running new<br />

rivers held the most intrigue for <strong>Roger</strong> and his<br />

contemporaries, but racing held the promise of money<br />

from the French Sports Authority. Just as today's<br />

paddlers might compete in freestyle events to earn<br />

sponsorship for their next paddling safari, so too did<br />

<strong>Roger</strong> and his peers race slalom in order to fund the next<br />

river trip.<br />

<strong>Paris</strong> raced C-1 and C-2. His partner, hand-picked by his<br />

coach Pean, was fellow Frenchman Claude Neveu. The<br />

<strong>Paris</strong>/Neveu duo captured the French National<br />

Championship in 1948, and attended their first World<br />

Championships the next year. The Rhone River course<br />

featured a huge wave that flipped the pair on their first<br />

run. Fortunately, the scoring format took the best time<br />

of two runs, and on their second attempt, <strong>Paris</strong> and<br />

Neveu aced the course, finishing second. They were<br />

elated. By the time they attended their next worlds in<br />

1951, <strong>Paris</strong> and Neveu were old pros. They won the race,<br />

and were crowned World Champions.<br />

Slalom racing, and the advanced techniques inherent in<br />

it, was well developed in Europe by the 1950s. Canoe<br />

clubs were established institutions. Whitewater<br />

paddling was a recognized and rapidly developing sport.<br />

On the other side of the Atlantic, it was a different story.<br />

There were a few paddling clubs and adventuresome<br />

river runners in America, but whitewater equipment and<br />

technique lagged far behind Europe. This gap between<br />

European and American paddling began to close in the<br />

1950s, and <strong>Roger</strong> <strong>Paris</strong> was one of the main reasons why.<br />

In 1953, <strong>Roger</strong> traveled to the United States to compete<br />

in what was known as the Salida Race. This downriver<br />

event on the Arkansas River in the state of Colorado held<br />

large cash prizes, which drew Europe's top paddlers<br />

throughout the 1950s. The influx of world-class talent<br />

brought advanced skills and cutting-edge boat designs<br />

never before seen in America. The first decked<br />

whitewater canoe in the U.S. debuted at the Salida<br />

Race, as did the first slalom course in the Western<br />

states. Many Americans saw their first duffek stroke in<br />

Salida, and the superiority of fiberglass boats over<br />

wooden foldboats was established there. American<br />

paddlers came to Salida to learn from the Europeans,<br />

and Europeans traveled there to see the American West,<br />

and maybe win a little cash. In the 1950s, the Salida<br />

Race was the place to be.<br />

<strong>Roger</strong>'s coach André Pean had traveled to the Salida<br />

Race in 1952, and returned with great tales of high<br />

mountains, big empty spaces, and dozens of rivers that<br />

had never felt the stroke of a paddle. <strong>Paris</strong> needed little<br />

convincing. At the age of 24, he boarded a ship and set<br />

sail for Colorado. <strong>Paris</strong>, along with Pean and Neveu,<br />

landed in New York and traveled by bus to Chicago.<br />

There they met a friend of a friend who agreed to drive<br />

the trio to Colorado.<br />

Like many who travel to the American West from more<br />

tame environs, <strong>Roger</strong> was stupefied by the highelevation<br />

sagebrush valleys, the obvious lack of people,<br />

and the vast expanses of absolute nothingness. In 1953<br />

there were no freeways dashing across mountain ranges,<br />

“If moderate runs<br />

like Brown’s<br />

Canyon [of the<br />

Arkansas River]<br />

were just starting<br />

to be explored,<br />

just think of how<br />

many unrun<br />

rivers must lurk<br />

in these<br />

mountains.”<br />

no ski resorts of transplanted opulence. <strong>Roger</strong><br />

passed through Vail on a winding two-lane road.<br />

"There was nothing there," he remembers.<br />

In the middle of this sparse, spacious landscape, the<br />

tiny town of Salida, Colorado became a rendezvous<br />

point for an international gathering of boaters ready<br />

for competition, good times, and whitewater. When<br />

it came time to race, <strong>Roger</strong> switched from his regular<br />

boat, a C-1, to a kayak, which he hoped would<br />

provide greater speed. Despite having limited<br />

experience in a kayak, he finished third, and came<br />

away with $300 in prize money. It was enough to<br />

travel on for a while, so after the race <strong>Paris</strong> and his<br />

companions stayed and explored the surrounding<br />

area.<br />

Not far upstream from the racecourse was Browns<br />

Canyon—a remote section of river that rollicks<br />

between fields of granite boulders interspersed with<br />

sparse gnarled pines. Today it is one of the most<br />

popular commercial raft runs in the world, a classic<br />

class III+ romp. In 1953, it had never been run, so<br />

<strong>Paris</strong> and crew gave it a try. Despite being seriously<br />

psyched for the first descent, the Europeans found it<br />

hardly challenging. They had run much harder rivers<br />

in their homeland. "If moderate runs like Browns<br />

Canyon were just starting to be explored," thought<br />

the Europeans, "just think of the many unrun rivers<br />

that must lurk in these mountains!" <strong>Roger</strong> and<br />

company would be back.<br />

The following summer, <strong>Roger</strong> returned to Colorado.<br />

He won the 1954 downriver race (again paddling an<br />

unfamiliar kayak), and promptly joined a half dozen<br />

other racers for a run down the Royal Gorge of the<br />

Arkansas. The Royal Gorge is as spectacular as its<br />

title implies. Granite walls rise vertically for nearly<br />

2,000 feet, looming ominously over the river below.<br />

In 1954, the gorge had been run once or twice<br />

previously, but many of the drops had been portaged,<br />

and it remained a big intimidating place.<br />

<strong>Roger</strong>'s group of seven consisted of three kayaks and<br />

two C-2's. A cadre of photographers and friends<br />

followed the paddlers from the platform of a flatbed<br />

railroad car, which ran along tracks beside the river.<br />

The paddlers launched on a powerful springtime flow.<br />

Surging brown water boiled and hissed beneath their<br />

cumbersome wooden boats. The carnage began at the<br />

first rapid when one of the kayakers pinned briefly<br />

and swam. After picking up the pieces, the group<br />

<strong>Roger</strong>, in an early fiberglass kayak design, gets ready for a downriver race on the Arkansas River in Salida, Colorado at one of the first Fibark Festivals (1958).<br />

made their way downstream to a much larger rapid.<br />

Here Basque kayaker Ray Zubiri entered a big hole<br />

and completely disappeared in his fifteen-foot-long<br />

boat. When his empty boat emerged from the froth,<br />

<strong>Roger</strong> recalls it was "twisted like taffy." The<br />

adventure was on. <strong>Paris</strong> and his C-2 partner Serge<br />

Michel were the first to probe the next major drop.<br />

<strong>Paris</strong> wrote of their run; "Once in the rapid every<br />

second was an emergency." Paddling with this type<br />

of urgency, it is no wonder that <strong>Paris</strong> and Michel's<br />

boat was one of the few that emerged from the<br />

imposing canyon unscathed.<br />

The fragility and sluggishness of wooden boats<br />

during the ’50s was becoming ever more apparent to<br />

those on the cutting edge of whitewater paddling,<br />

and a concerted search for something better was<br />

underway. When <strong>Roger</strong> returned to Europe in the<br />

summer of 1954, he stumbled into the avante-garde<br />

world of boat design in his hometown of Orleans. At<br />

<strong>Roger</strong>'s suggestion, a fiberglass roofing manufacturer<br />

in Orleans agreed to build a fiberglass whitewater<br />

boat, one of the first ever made. <strong>Paris</strong> and Neveu<br />

began racing with the new boat, and their success<br />

created a paradigm shift in boat construction that<br />

lasted throughout the next two decades. It wasn't<br />

until 1958, however, that the most seminal event in<br />

fiberglass' acceptance occurred. Once again, the<br />

moment came at the Salida race, and <strong>Roger</strong> <strong>Paris</strong> was<br />

the driving force behind the change.<br />

Californian Tom Telefson came to the Salida Race<br />

with a long fiberglass boat that was crafted after a<br />

Swedish flatwater design—fast and unstable. In the<br />

days before the race, Telefson realized that his sleek<br />

race boat was too much for him to handle, and he<br />

began looking for a more forgiving boat. <strong>Roger</strong> saw<br />

the potential speed in Telefson's boat, and was more<br />

than willing to make a trade. He exchanged his<br />

folding Klepper kayak for Telefson's race boat, and<br />

won the 1958 Salida race definitively.<br />

Back in Europe, news of <strong>Paris</strong>' victory in the new boat<br />

material spread, and more racers began paddling<br />

fiberglass. Soon a new, separate race class was<br />

established for fiberglass boats. By 1965, wooden<br />

boats were virtually gone from the scene. The reign<br />

of fiberglass had begun.<br />

52<br />

53

Although he was a key proponent of new boats and their<br />

construction, it was more so <strong>Roger</strong>'s refined paddling<br />

technique that put him a notch above most other<br />

paddlers. He was always willing to share tips with<br />

inquiring river runners. One of those who queried <strong>Roger</strong><br />

for instruction was Bob Hermann, a spirited but<br />

unpolished American who had won the Salida Race<br />

before <strong>Roger</strong> and his European cohorts had started<br />

entering. Hermann invited <strong>Roger</strong> to his California ranch<br />

before the 1954 race to learn new and better techniques<br />

from the Frenchman. They ran the Klamath, Trinity, Eel,<br />

Russian, Merced, and Mokelumne Rivers in an era when<br />

the sight of river kayakers brought curious stares from<br />

nearly anyone. If you saw a kayaker in those days, it<br />

was likely to be <strong>Roger</strong>. He soon became a recognized<br />

figure on rivers in California and throughout the<br />

American West.<br />

In 1960, <strong>Roger</strong> joined California paddling pioneers<br />

Maynard Munger and Bryce Whitmore for an attempted<br />

first descent of Kings Canyon in the southern Sierra<br />

Nevadas. Munger had fished along the river, and felt that<br />

with the right team, the class V river canyon could be<br />

run. He called <strong>Paris</strong> and promised towering canyon<br />

walls, granite boulders, congested frothing whitewater,<br />

deep clear pools, and virgin sand beaches. <strong>Roger</strong> was<br />

nursing an injured knee from the previous ski season,<br />

but the temptation of a new upper-limits wilderness run<br />

was too great to resist.<br />

run of Kings Canyon, but more significantly they had<br />

made the first descent of any major class V river in<br />

California's Sierra—a region that continues to challenge<br />

expedition paddlers today.<br />

By the early 1960s, <strong>Roger</strong> had clearly influenced the<br />

sport of whitewater, yet his biggest contribution was yet<br />

to come. The Colorado Rocky Mountain School near<br />

Aspen, Colorado was an alternative college preparatory<br />

institution with a focus on outdoor activities. Kayaking,<br />

skiing, and French language were all registered courses<br />

at the school, so when <strong>Roger</strong>'s friend Walter Kirschbaum<br />

(a legendary German paddler who pioneered several of<br />

America's Western rivers) suggested that <strong>Roger</strong> come<br />

and join him at the school as an assistant instructor, it<br />

was a natural fit. <strong>Roger</strong> and his wife Jackie packed up<br />

their Volkswagen bus and drove from their coastal<br />

California residence to the Roaring Fork Valley of<br />

Colorado in 1964.<br />

<strong>Roger</strong> taught French language, Nordic and alpine skiing,<br />

and of course, whitewater paddling. Two years after<br />

starting with the school, <strong>Roger</strong> began his own <strong>Roger</strong><br />

<strong>Paris</strong> Kayak School, operating during summers on the<br />

rivers of the Roaring Fork Valley. It quickly became the<br />

leading kayak instructional center in North America. The<br />

<strong>Roger</strong> <strong>Paris</strong> name was an instant attention grabber, and<br />

the instruction itself was top-tier.<br />

Throughout the late ’60s and ’70s, <strong>Roger</strong> could be found<br />

with his wife Jackie and a crew of instructors teaching<br />

When not on the slopes, <strong>Roger</strong> is often at his TV-less,<br />

telephone-less cabin on the headwaters of the Crystal<br />

River in the heart of the Rockies. If you can find him,<br />

you might get him to tell you a snippet or two from his<br />

life of adventure. There was the time during the war<br />

when he acquired a gun and was stopped just short of<br />

entering a deadly battle, or the time he rowed the<br />

Middle Fork of the Salmon at flood stage, or when he<br />

paddled solo down the Green River, or when he hiked<br />

into the Maze of Canyonlands National Park for a week,<br />

then paddled back upstream so he didn't have to run a<br />

shuttle. Or maybe he'll tell of more commonplace but no<br />

less amazing moments, like the birth of his sons Mitch<br />

and Sasha.<br />

In any case, <strong>Roger</strong> has plenty of stories to tell, and<br />

plenty for us to learn from. Fortunately, many of us have<br />

felt <strong>Roger</strong>'s touch. His realm of influence has grown<br />

from the nucleus of his school on the Roaring Fork, and<br />

spread with his students throughout the Rocky<br />

Mountains, across the continent eastward, and farther<br />

still across the ocean back to its roots where a twelve<br />

year old boy steered his canoe through a rapid of<br />

bombed bridge debris, dodging the hazards, surfing the<br />

waves, and finally moving downstream to see what the<br />

next horizon held in store.<br />

<strong>Roger</strong>, in the stern, and Claude Neveu, in the bow, training in a brand new fiberglass canoe in Augsburg - Germany before the Slalom World Championships (1957).<br />

PROFILE<br />

The trio started down the clear mountain river, weaving<br />

through class III and IV rapids of perfect polished<br />

granite. A couple miles into the run, they arrived at<br />

their first scout as the river dropped below the horizon,<br />

revealing only white spray suspended in the morning<br />

sunshine. After a quick look, the rapid seemed runnable,<br />

and <strong>Roger</strong> led through. After a short pool was another<br />

drop requiring a scout, then another, and another. By<br />

early afternoon they had scouted nearly two-dozen<br />

boulder-strewn rapids, running most and portaging a<br />

few. The relentless whitewater kept coming. They<br />

labored through a narrow section of canyon where<br />

waterfalls poured in from the sides, and class V rapids<br />

filled the riverbed. Munger knew that even the<br />

fisherman didn't come here.<br />

The trio's calculated pace continued through the<br />

afternoon as the sun sank behind the canyon walls, and<br />

twilight seeped into their world of water and rock.<br />

Finally it became too dark to paddle, and the weary<br />

explorers curled up on a sandy beach for a miserable<br />

night in their wet suits. In the morning, they found that<br />

the rapids relented a short distance downstream, and<br />

the team greeted their worried shuttle driver (<strong>Roger</strong>'s<br />

wife Jackie) by mid-morning. They had made the first<br />

an ever-new crop of students how to hit their first roll,<br />

or run their first rapid. <strong>Roger</strong>'s instructional progression<br />

would begin on a pond before moving students to the<br />

Roaring Fork and Colorado Rivers. For the best kayakers,<br />

the classroom would then shift to more difficult runs like<br />

the nearby Crystal River.<br />

Legions of paddlers got started in the sport through<br />

<strong>Roger</strong>'s tutelage, and some went on to become high<strong>profile</strong><br />

paddlers in their own right. Nine-time US<br />

National Slalom Champion Eric Evans was a <strong>Roger</strong><br />

protégé, along with racers Jon Fishburn, Linda Harrison,<br />

Rich Weiss, and David Nutt—all National Champions.<br />

Other notable <strong>Roger</strong> students include Andy Corra, Jennie<br />

Goldberg, and Nancy Wiley and her sisters, Amy and<br />

Janet.<br />

In the ’80s <strong>Roger</strong> took over as professor of outdoor<br />

recreation at Colorado Mountain College in Glenwood<br />

Springs, Colorado. This tenure lasted through 1987,<br />

when <strong>Roger</strong>'s unofficial retirement began. His mountain<br />

lifestyle, however, has shown no signs of letting up.<br />

Since the ’80s, <strong>Roger</strong> has ski instructed at several of the<br />

biggest mountain resorts in Colorado, his latest favorite<br />

being Crested Butte, where he teaches for Club Med.<br />

Loving both rivers and mountains his whole life, <strong>Roger</strong> carves some<br />

turns at Crested Butte Ski Area, Colorado (2005).<br />

54<br />

47