The Ford Boys (pdf) - Wisconsin Alumni Association

The Ford Boys (pdf) - Wisconsin Alumni Association

The Ford Boys (pdf) - Wisconsin Alumni Association

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

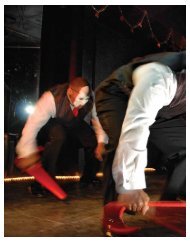

COURTESY OF LOUISE TRUBEK (2)<br />

<strong>The</strong>re was no room for<br />

the <strong>Ford</strong> scholars in the<br />

UW’s residence halls, so<br />

their adviser, Herbert<br />

Howe, found them other<br />

accommodations. Louise<br />

Trubek (sitting on step,<br />

second from top) lived<br />

at Groves Co-Op during<br />

her junior year and<br />

found that the diverse<br />

mix of people there<br />

added another dimension<br />

to her education.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Conant Plan made college officials nervous. If all eighteen-year-old<br />

males entered the army, they reasoned, most would never return to school,<br />

depriving the country of a generation of talent.<br />

taking a student deferment and going to<br />

college. This not only deprived the armed<br />

forces of manpower, but many felt it was<br />

unfair. <strong>The</strong> editors of <strong>The</strong> Nation complained<br />

that exempting the college-bound<br />

created “an aristocracy of draft-proof<br />

students on the basis of aptitude tests and<br />

from the economically most fortunate<br />

groups. <strong>The</strong> dumb young men,” they<br />

noted sarcastically, “can do the fighting.”<br />

To address the inequity, a group<br />

called the Committee on the Present<br />

Danger suggested doing away with<br />

student deferments altogether. As it was<br />

led by Harvard University president<br />

James Conant and prominent scientist<br />

Vannevar Bush, many people listened —<br />

including George Marshall, the secretary<br />

of defense, who requested that Congress<br />

adopt the idea.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Conant Plan made college officials<br />

nervous. If all eighteen-year-old<br />

males entered the army, they reasoned,<br />

most would never return to school,<br />

depriving the country of a generation of<br />

talent. In January 1951, members of the<br />

<strong>Association</strong> of American Colleges met in<br />

Atlantic City, New Jersey, to voice their<br />

concerns. While they wrung their hands,<br />

Mark Ingraham MA’22, the UW’s dean<br />

of Letters and Science, met privately<br />

with his counterparts from Columbia,<br />

Yale, and Chicago to come up with a<br />

plan to deal with the looming problem.<br />

Aiming “to preserve the values of general,<br />

liberal education during the protracted<br />

period of emergency which the<br />

nation now faces,” they proposed running<br />

an experiment: suppose that America’s<br />

brightest young men were invited to<br />

college two years early — would they<br />

have the minds and maturity to handle<br />

the load<br />

<strong>The</strong> deans reasoned that boys who’d<br />

had a taste of college would be more<br />

likely to return after a hitch in the military.<br />

Moreover, they would provide the<br />

army with a nucleus of educated soldiers<br />

to fill emerging high-tech duties, especially<br />

in medicine. It seemed like a good<br />

plan for everyone — all the deans needed<br />

was someone to fund it.<br />

Enter the Revenue Act of 1950. Like<br />

the Conant Plan for the draft, this law<br />

tried to create a more equitable society,<br />

using taxation as its tool. Many in Congress<br />

felt that big businesses and wealthy<br />

families were using charitable foundations<br />

to conceal their money from the<br />

IRS. <strong>The</strong> Act opened foundation tax<br />

returns to public scrutiny so that the<br />

people (who, Congress reasoned, were<br />

supposed to be the charities’ ultimate<br />

beneficiaries) could know just how such<br />

funds were managed.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ford</strong> Foundation was one of the<br />

targets of this provision. In 1950, it had<br />

a declared value of half a billion dollars,<br />

though some estimates put its actual<br />

value at $2.5 billion, significantly more<br />

than the assets of all other American<br />

foundations combined. But it had only<br />

paid out some $27 million for charitable<br />

works over the previous fifteen years. An<br />

internal study concluded that the foundation<br />

could afford to spend that much<br />

every year without depleting its endowment,<br />

and to some outsiders, it appeared<br />

32 ON WISCONSIN