8 MB - University of Toronto Magazine

8 MB - University of Toronto Magazine

8 MB - University of Toronto Magazine

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Leading Edge<br />

The problem is that different mechanisms<br />

in the brain might be working together to<br />

produce similar symptoms in patients.<br />

In an effort to tease apart these different<br />

mechanisms and to find ways to predict how<br />

different types <strong>of</strong> depression will respond to<br />

treatments, the researchers are recruiting 300<br />

patients and 100 healthy subjects at six academic<br />

centres across Canada. The study will take three<br />

years. The researchers will look to see which<br />

gene variants the study participants have and<br />

which proteins those genes produce, with a<br />

particular focus on those known to play a role<br />

in depression or in how the body processes antidepressants.<br />

The researchers will also assess<br />

the patients for anxiety and how clearly they are<br />

able to think, take their family medical history<br />

and note any traumatic life events. Finally, they<br />

will use EEG to map brainwave activity and<br />

functional magnetic resonance imaging to track<br />

bloodflow to see what’s going on in the depressed<br />

– or recovering – person’s brain.<br />

These data are being collected at three points<br />

in the study: before starting on medication, two<br />

weeks after starting, and at the eight-week mark.<br />

All patients will take the same drug, escitalopram.<br />

Kennedy’s aim is to find out what distinguishes<br />

the people who do well quickly, the people who<br />

do well eventually and the people who never do<br />

well on a given antidepressant. It may be that<br />

people with a certain combination <strong>of</strong> genes plus<br />

certain brain imaging and blood results can be<br />

identified in advance as good responders. “We<br />

believe if we combine enough <strong>of</strong> these markers,<br />

we will be able to predict the right treatment for<br />

individual patients,” he says.<br />

Kennedy expects that, once it is easier to predict<br />

who benefits from what, drug companies<br />

will begin to target their medications more specifically.<br />

Rather than claiming only 40 per cent<br />

<strong>of</strong> all depressed patients improved, for instance,<br />

they might be able to claim 80 or 90 per cent in<br />

particular subpopulations – groups that will be<br />

objectively identified through biomarkers.<br />

In the end, says Kennedy, biomarkers will not<br />

only help confirm which people do have depression,<br />

what type <strong>of</strong> depression they have and<br />

what medication might work best, they may also<br />

point the way to the causes – leading to novel<br />

treatments. – Alison Motluk<br />

Property Value<br />

<strong>Toronto</strong>’s land-use maps are<br />

important planning tools but they lack<br />

detail and are <strong>of</strong>ten out-<strong>of</strong>-date.<br />

Not for much longer<br />

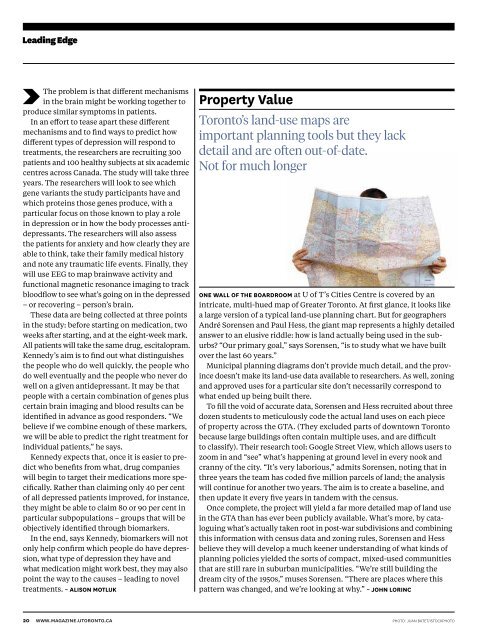

One wall <strong>of</strong> the boardroom at U <strong>of</strong> T’s Cities Centre is covered by an<br />

intricate, multi-hued map <strong>of</strong> Greater <strong>Toronto</strong>. At first glance, it looks like<br />

a large version <strong>of</strong> a typical land-use planning chart. But for geographers<br />

André Sorensen and Paul Hess, the giant map represents a highly detailed<br />

answer to an elusive riddle: how is land actually being used in the suburbs<br />

“Our primary goal,” says Sorensen, “is to study what we have built<br />

over the last 60 years.”<br />

Municipal planning diagrams don’t provide much detail, and the province<br />

doesn’t make its land-use data available to researchers. As well, zoning<br />

and approved uses for a particular site don’t necessarily correspond to<br />

what ended up being built there.<br />

To fill the void <strong>of</strong> accurate data, Sorensen and Hess recruited about three<br />

dozen students to meticulously code the actual land uses on each piece<br />

<strong>of</strong> property across the GTA. (They excluded parts <strong>of</strong> downtown <strong>Toronto</strong><br />

because large buildings <strong>of</strong>ten contain multiple uses, and are difficult<br />

to classify). Their research tool: Google Street View, which allows users to<br />

zoom in and “see” what’s happening at ground level in every nook and<br />

cranny <strong>of</strong> the city. “It’s very laborious,” admits Sorensen, noting that in<br />

three years the team has coded five million parcels <strong>of</strong> land; the analysis<br />

will continue for another two years. The aim is to create a baseline, and<br />

then update it every five years in tandem with the census.<br />

Once complete, the project will yield a far more detailed map <strong>of</strong> land use<br />

in the GTA than has ever been publicly available. What’s more, by cataloguing<br />

what’s actually taken root in post-war subdivisions and combining<br />

this information with census data and zoning rules, Sorensen and Hess<br />

believe they will develop a much keener understanding <strong>of</strong> what kinds <strong>of</strong><br />

planning policies yielded the sorts <strong>of</strong> compact, mixed-used communities<br />

that are still rare in suburban municipalities. “We’re still building the<br />

dream city <strong>of</strong> the 1950s,” muses Sorensen. “There are places where this<br />

pattern was changed, and we’re looking at why.” – John Lorinc<br />

20 WWW.MAGAZINE.UTORONTO.CA<br />

photo: Juan Batet/iSTOCKPHOTO