PACIFIC BLUEFIN TUNA â TROLL CAUGHT Thunnus orientalis ...

PACIFIC BLUEFIN TUNA â TROLL CAUGHT Thunnus orientalis ...

PACIFIC BLUEFIN TUNA â TROLL CAUGHT Thunnus orientalis ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>PACIFIC</strong> <strong>BLUEFIN</strong> <strong>TUNA</strong> – <strong>TROLL</strong> <strong>CAUGHT</strong><br />

<strong>Thunnus</strong> <strong>orientalis</strong><br />

Sometimes known as Bluefin Tuna, Northern Bluefin, Kuro maguro<br />

SUMMARY<br />

Pacific Bluefin Tuna are commonly caught by troll fishing, which has very low levels of bycatch<br />

and causes no habitat damage. They are typically found in the North Pacific, and can travel huge<br />

distances from their spawning grounds in the western Pacific to the eastern Pacific. Pacific<br />

Bluefin Tuna are fished for by many countries including Japan, U.S., and Mexico, and they are<br />

prized on the sashimi market. Due to high demand and market value, fishing pressure is too high<br />

and Pacific Bluefin Tuna are uncommon. Chef Barton Seaver cautions: “Bluefin is the king of<br />

the sea. It is the fattiest, richest fish in the ocean. Bluefin's unique flavor contributes to its great<br />

appeal. However, we have eaten our way through this species' ranks and have forfeited our<br />

ability to consume this fish. It is a taste that may be lost for many generations to come, maybe<br />

forever. However, in most preparations, Bluefin can be substituted by pole-caught Yellowfin<br />

tuna which, although not quite as elegant, is a great eating experience. For preparations such as<br />

grilled tuna, try to seek out Albacore or even the tuna cousin, Wahoo.”<br />

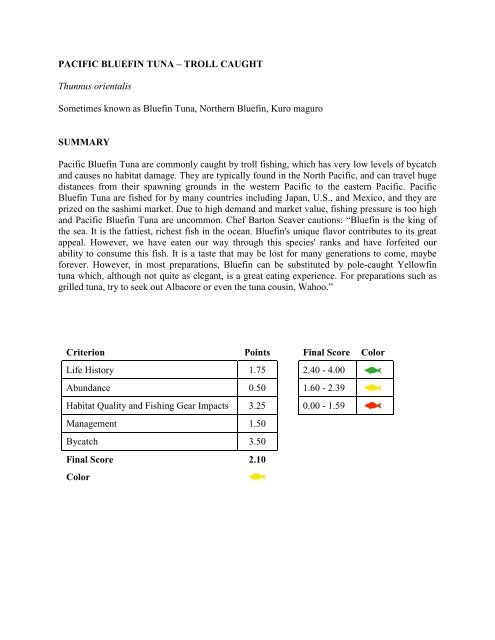

Criterion Points Final Score Color<br />

Life History 1.75 2.40 - 4.00<br />

Abundance 0.50 1.60 - 2.39<br />

Habitat Quality and Fishing Gear Impacts 3.25 0.00 - 1.59<br />

Management 1.50<br />

Bycatch 3.50<br />

Final Score 2.10<br />

Color

LIFE HISTORY<br />

Core Points (only one selection allowed)<br />

If a value for intrinsic rate of increase („r‟) is known, assign the score below based on this value.<br />

If no r-value is available, assign the score below for the correct age at 50% maturity for females<br />

if specified, or for the correct value of growth rate ('k'). If no estimates of r, age at 50% maturity,<br />

or k are available, assign the score below based on maximum age.<br />

1.00 Intrinsic rate of increase 10 years; OR growth rate<br />

30 years.<br />

2.00 Intrinsic rate of increase = 0.05-0.15; OR age at 50% maturity = 5-10 years; OR a<br />

growth rate = 0.16–0.30; OR maximum age = 11-30 years.<br />

Sexual maturity begins at 150 cm or 5 years of age in the Pacific Ocean, while in the Sea<br />

of Japan maturity occurs at a younger age of 3 years or 120 cm (Tanaka 2006). Growth<br />

rates (k) of Pacific Bluefin Tuna Pacific Bluefin Tuna have been estimated to range from<br />

0.104 to 0.195 and maximum ages have been estimated to be 26 years (Yukinawa and<br />

Yabuta 1967, Shimose et al. 2008, and Shimose et al. 2009). Pacific Bluefin Tuna can<br />

reach a maximum size of 300 cm and weight of 450 kg. (Fishbase 2009).<br />

3.00 Intrinsic rate of increase >0.16; OR age at 50% maturity = 1-5 years; OR growth rate<br />

>0.30; OR maximum age

-0.25 Species has a strategy for sexual development that makes it especially vulnerable to<br />

fishing pressure (e.g., age at 50% maturity >20 years; sequential hermaphrodites;<br />

extremely low fecundity).<br />

-0.25 Species has a small or restricted range (e.g., endemism; numerous evolutionarily<br />

significant units; restricted to one coastline; e.g., American lobster; striped bass; endemic<br />

reef fishes).<br />

-0.25 Species exhibits high natural population variability driven by broad-scale<br />

environmental change (e.g. El Nino; decadal oscillations).<br />

Studies to determine the effect of global warming on Pacific Bluefin Tuna distributions<br />

have been started but the trends are difficult to interpret (Yamada et al. 2009). Pacific<br />

Bluefin Tuna spawn in waters around 26º C and prefer water around 18ºC during their<br />

migrations, which appear to be influenced by prey abundance and ocean currents<br />

(Inageke et al. 2001). Fluctuations of peak recruitments in the 1950‟s and 1970‟s<br />

corresponded with weak Aleutian Low, warm sea surface temperatures (SST) in the<br />

central North Pacific and spawning areas (ISC 2008). Significant correlations between<br />

Pacific Bluefin Tuna recruitment and Pacific Decadal Oscillation have been noted (ISC<br />

2008). Data also shows that high recruitment occurs during periods of high temperatures<br />

in spawning areas (ISC 2008).<br />

+0.25 Species does not have special behaviors that increase ease or population consequences of<br />

capture OR has special behaviors that make it less vulnerable to fishing pressure (e.g.,<br />

species is widely dispersed during spawning).<br />

+0.25 Species has a strategy for sexual development that makes it especially resilient to fishing<br />

pressure (e.g., age at 50% maturity

ABUNDANCE<br />

Core Points (only one selection allowed)<br />

Compared to natural or un-fished level, the species population is:<br />

1.00 Low: Abundance or biomass is 125% of BMSY or similar proxy.<br />

Points of Adjustment (multiple selections allowed)<br />

-0.25 The population is declining over a generational time scale (as indicated by biomass<br />

estimates or standardized CPUE).<br />

Standardized catch per unit effort (CPUE) for longline fisheries indicated that abundance<br />

increased during the early to late 1990‟s (Yamada et al. 2009). Abundances have<br />

fluctuated since the peaks in the late 1990‟s but appear to have decreased in recent years<br />

(Yamada et al. 2009). Standardized CPUE indices are difficult to interpret for this species<br />

because of changes in gear configurations and fishing grounds over time (ISC 2008). The<br />

longline CPUE is thought to be a good representative of the trends in abundance for adult<br />

Pacific Bluefin Tuna (ISC 2008). Peaks in abundance occurred in the 1960‟s, 1970‟s,<br />

early 1990‟s and 2000 but have since gradually declined (ISC 2008).

-0.25 Age, size or sex distribution is skewed relative to the natural condition (e.g.,<br />

truncated size/age structure or anomalous sex distribution).<br />

The size of Pacific Bluefin Tunas caught depends on the individual fisheries targeting<br />

them (Yamada et al. 2009). Trolling vessels in the western and central Pacific Ocean<br />

catch juvenile Pacific Bluefin Tuna (15-30 cm) from July through October (IATTC<br />

2008). From November through April larger (35-60 cm) juvenile Pacific Bluefin Tuna<br />

are taken by trolling (IATTC 2008). Overall the majority of Pacific Bluefin Tuna caught<br />

are considered „small‟ (Yamada et al. 2009). Sex to size ratio is also skewed, with a<br />

higher proportion of females less than 160 cm (ISC 2008).<br />

-0.25 Species is listed as "overfished" OR species is listed as "depleted", "endangered",<br />

or "threatened" by recognized national or international bodies.<br />

The results of the latest population assessment indicate that current fishing mortality is<br />

too high (ISC 2009) but Pacific Bluefin Tuna are not considered overfished.<br />

-0.25 Current levels of abundance are likely to jeopardize the availability of food for other<br />

species or cause substantial change in the structure of the associated food web.<br />

+0.25 The population is increasing over a generational time scale (as indicated by biomass<br />

estimates or standardized CPUE).<br />

+0.25 Age, size or sex distribution is functionally normal.<br />

+0.25 Species is close to virgin biomass.<br />

+0.25 Current levels of abundance provide adequate food for other predators or are not<br />

known to affect the structure of the associated food web.<br />

It is not known if current levels of Pacific Bluefin Tuna abundance will affect the<br />

associated food web. We have not added or subtracted points due to this lack of<br />

knowledge.<br />

0.50 Points for Abundance

HABITAT QUALITY AND FISHING GEAR IMPACTS<br />

Core Points (only one selection allowed)<br />

Select the option that most accurately describes the effect of the fishing method upon the habitat<br />

that it affects<br />

1.00 The fishing method causes great damage to physical and biogenic habitats (e.g., cyanide;<br />

blasting; bottom trawling; dredging).<br />

2.00 The fishing method does moderate damage to physical and biogenic habitats (e.g., bottom<br />

gillnets; traps and pots; bottom longlines).<br />

3.00 The fishing method does little damage to physical or biogenic habitats (e.g., hand<br />

picking; hand raking; hook and line; pelagic long lines; mid-water trawl or gillnet;<br />

purse seines).<br />

Most Pacific Bluefin Tuna are caught using purse seines, longlines and troll gear, with<br />

some fish also caught by pole and line, set and drift nets (Yamada et al. 2009, and ISC<br />

2008). Japanese trolling vessels catch about 25% or 3,000-5,000 mt (per year) of the total<br />

Japanese catch of Pacific Bluefin Tuna (Yamada et al. 2009). Trolling does very little<br />

damage to the physical habitat (Chupenpagdee et al. 2003).<br />

Points of Adjustment (multiple selections allowed)<br />

-0.25 Habitat for this species is so compromised from non-fishery impacts that the ability of the<br />

habitat to support this species is substantially reduced (e.g., dams; pollution; coastal<br />

development).<br />

-0.25 Critical habitat areas (e.g., spawning areas) for this species are not protected by<br />

management using time/area closures, marine reserves, etc.<br />

Time area closures are not in place in the spawning grounds of Pacific Bluefin Tunas.<br />

-0.25 No efforts are being made to minimize damage from existing gear types OR new or<br />

modified gear is increasing habitat damage (e.g., fitting trawls with roller rigs or<br />

rockhopping gear; more robust gear for deep-sea fisheries).<br />

-0.25 If gear impacts are substantial, resilience of affected habitats is very slow (e.g., deep<br />

water corals; rocky bottoms).<br />

+0.25 Habitat for this species remains robust and viable and is capable of supporting this<br />

species.<br />

Oceanic habitat is likely healthy enough to support Bluefin Tuna populations.

+0.25 Critical habitat areas (e.g., spawning areas) for this species are protected by management<br />

using time/area closures, marine reserves, etc.<br />

+0.25 Gear innovations are being implemented over a majority of the fishing area to<br />

minimize damage from gear types OR no innovations necessary because gear effects<br />

are minimal.<br />

Habitat effects of trolling for Pacific Bluefin Tuna are minimal.<br />

+0.25 If gear impacts are substantial, resilience of affected habitats is fast (e.g., mud or sandy<br />

bottoms) OR gear effects are minimal.<br />

3.25 Points for Habitat Quality and Fishing Gear Impacts<br />

MANAGEMENT<br />

Core Points (only one selection allowed)<br />

Select the option that most accurately describes the current management of the fisheries of this<br />

species.<br />

1.00 Regulations are ineffective (e.g., illegal fishing or overfishing is occurring) OR the<br />

fishery is unregulated (i.e., no control rules are in effect).<br />

2.00 Management measures are in place over a major portion over the species' range but<br />

implementation has not met conservation goals OR management measures are in<br />

place but have not been in place long enough to determine if they are likely to<br />

achieve conservation and sustainability goals.<br />

Pacific Bluefin Tuna are managed by the West and Central Pacific Fishery Commission<br />

(WCPFC) and the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC). Population<br />

assessments are completed by the International Scientific Committee for tuna and tunalike<br />

species in the North Pacific Ocean (ISC).<br />

The WCPFC introduced several new management efforts for Pacific Bluefin Tuna after<br />

the 2008 population assessment (WCPFC 2008), such as fishing effort north of 20° N<br />

shall not increase from current levels and increasing the data collection system (WCPFC<br />

2008). Previously enacted management efforts include vessel monitoring systems<br />

(WCPFC 2007) and observer programs (WCPFC 2007b). The IATTC has not<br />

implemented any conservation measured aimed at Pacific Bluefin Tuna.

3.00 Substantial management measures are in place over a large portion of the species range<br />

and have demonstrated success in achieving conservation and sustainability goals.<br />

Points of Adjustment (multiple selections allowed)<br />

-0.25 There is inadequate scientific monitoring of stock status, catch or fishing effort.<br />

Uncertainty within the population assessment process for Pacific Bluefin Tuna is caused<br />

by a need for additional biological information such as size patterns, and growth and<br />

maturity rates, as well as enhanced collection of detailed data from many small-scale<br />

fisheries (Miyake et al. 2004). Additionally, there are problems associated with catch and<br />

effort estimates for several fisheries (Yamada et al. 2009).<br />

-0.25 Management does not explicitly address fishery effects on habitat, food webs, and<br />

ecosystems.<br />

-0.25 This species is overfished and no recovery plan or an ineffective recovery plan is in<br />

place.<br />

Although not considered overfished, abundance of Pacific Bluefin Tuna is very low and<br />

recovery plans do not appear to be effective.<br />

-0.25 Management has failed to reduce excess capacity in this fishery or implements<br />

subsidies that result in excess capacity in this fishery.<br />

Reductions in capacity in other fisheries, such as the purse seine fisheries, are needed to<br />

increase the abundance of large tuna species like Pacific Bluefin Tuna (Miyake 2005).<br />

+0.25 There is adequate scientific monitoring, analysis and interpretation of stock status, catch<br />

and fishing effort.<br />

+0.25 Management explicitly and effectively addresses fishery effects on habitat, food<br />

webs, and ecosystems.<br />

The Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission and West Pacific Fishery Management<br />

Council address fishery effects on ecosystem components such as trophic interactions and<br />

the physical environment (IATTC 2008, and WPFMC 2008).<br />

+0.25 This species is overfished and there is a recovery plan (including benchmarks, timetables<br />

and methods to evaluate success) in place that is showing signs of success OR recovery<br />

plan is not needed.

+0.25 Management has taken action to control excess capacity or reduce subsidies that result in<br />

excess capacity OR no measures are necessary because fishery is not overcapitalized.<br />

1.50 Points for Management<br />

BYCATCH<br />

Core Points (only one selection allowed)<br />

Select the option that most accurately describes the current level of bycatch and the<br />

consequences that result from fishing this species. The term, "bycatch" used in this document<br />

excludes incidental catch of a species for which an adequate management framework exists. The<br />

terms, "endangered, threatened, or protected," used in this document refer to species status that is<br />

determined by national legislation such as the U.S. Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Marine<br />

Mammal Protection Act (or another nation's equivalent), the IUCN Red List, or a credible<br />

scientific body such as the American Fisheries Society.<br />

1.00 Bycatch in this fishery is high (>100% of targeted landings), OR regularly includes a<br />

"threatened, endangered or protected species."<br />

2.00 Bycatch in this fishery is moderate (10-99% of targeted landings) AND does not<br />

regularly include "threatened, endangered or protected species" OR level of bycatch is<br />

unknown.<br />

3.00 Bycatch in this fishery is low (

-0.25 Bycatch of this species (e.g., undersize individuals) in other fisheries is high OR bycatch<br />

of this species in other fisheries inhibits its recovery, and no measures are being taken to<br />

reduce it.<br />

-0.25 The continued removal of the bycatch species contributes to its decline.<br />

+0.25 Measures taken over a major portion of the species range have been shown to<br />

reduce bycatch of "threatened, endangered, or protected species" or bycatch rates<br />

are no longer deemed to affect the abundance of the "protected" bycatch species<br />

OR no measures needed because fishery is highly selective (e.g., harpoon; spear).<br />

Troll fisheries are very selective and have very low bycatch of „threatened, endangered or<br />

protected‟ species. The Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) has several<br />

measures in place to reduce bycatch that include industry education and observer<br />

programs (IATTC 2008).<br />

+0.25 There is bycatch of targeted (e.g., undersize individuals) or non-targeted species in<br />

this fishery and measures (e.g., gear modifications) have been implemented that<br />

have been shown to reduce bycatch over a large portion of the species range OR no<br />

measures are needed because fishery is highly selective (e.g., harpoon; spear).<br />

Bycatch in the Pacific Bluefin Tuna fishery is very low (IATTC personal communication<br />

2009).<br />

+0.25 Bycatch of this species in other fisheries is low OR bycatch of this species in other<br />

fisheries inhibits its recovery, but effective measures are being taken to reduce it over a<br />

large portion of the range.<br />

+0.25 The continued removal of the bycatch species in the targeted fishery has had or will<br />

likely have little or no impact on populations of the bycatch species OR there are no<br />

significant bycatch concerns because the fishery is highly selective (e.g., harpoon; spear).<br />

3.50 Points for Bycatch

REFERENCES<br />

Aires-da-Silva, A., Compean, G. and Dreyfus, M. 2008. An historical overview of the bluefin<br />

fishery in the Eastern Pacific Ocean: past and future. World symposium for the study into the<br />

stock fluctuations of northern bluefin tunas (<strong>Thunnus</strong> thynnus and <strong>Thunnus</strong> <strong>orientalis</strong>), including<br />

the historic periods. April, 22-24, Spain. 33 p.<br />

Chen, K., Crone, P. and Hsu, C. 2009. Reproductive biology of female Pacific bluefin tuna<br />

<strong>Thunnus</strong> <strong>orientalis</strong> from south-western North Pacific. Fisheries Science 72:985-994.<br />

Chuenpagdee, R., Morgan, L.E., Maxwell, S.M., Norse, E.A., and Pauly, D. 2003. Shifting<br />

gears: assessing collateral impacts of fishing methods in US waters. Frontiers in Ecology and the<br />

Environment 1:517-524.<br />

Fishbase. 2009. Species Summary: <strong>Thunnus</strong> <strong>orientalis</strong>. Accessed on 8/25/2009. Online:<br />

http://www.fishbase.com/Summary/SpeciesSummary.phpid=14290<br />

Inagake, D., Yamada, H., Segawa, K., Okazaki, M., Nitta, A., and Itoh, T. 2001. Migration of<br />

young bluefin tuna, <strong>Thunnus</strong> <strong>orientalis</strong> Temminck et Schlegel, through archival tagging<br />

experiments and its relation with oceanographic condition in the western North Pacific. Bulletin<br />

of Natural Research from the Institute for Far Seas Fisheries 38:53-81.<br />

Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC). 2008. Fishery status report No. 6: Tunas<br />

and billfishes in the eastern Pacific Ocean in 2007. La Jolla, CA. 145 p. Online: www.iattc.org/<br />

FisheryStatusReportsENG.htm<br />

International Scientific Committee for Tuna and Tuna-like Species in the North Pacific Ocean<br />

(ISC). 2008. Report of the Pacific bluefin tuna working group workshop. Shimizu, Japan, May<br />

28-June 4, 2008. 67 p. Online: http://isc.ac.affrc.go.jp/isc9/ISC9rep.html<br />

International Scientific Committee for Tuna and Tuna-like Species in the North Pacific Ocean<br />

(ISC). 2009. Report of the Pacific bluefin tuna working group workshop. Kaoshiun, Taiwan, July<br />

10-11, 2009. 14 p. Online: http://isc.ac.affrc.go.jp/isc9/ISC9rep.html<br />

Itoh, T., Tsuhi, S. and Nitta, A. 2003. Migration patterns of young Pacific bluefin tuna (<strong>Thunnus</strong><br />

<strong>orientalis</strong>) determined with archival tags. Fisheries Bulletin 101:514-534<br />

Masuma, S. 2008. Biological information from Pacific bluefin tuna fisheries. BFT SYM/034,<br />

Santander, Spain 2008. 21 p. Online: http://www.iccat.int/Documents/Meetings/ Docs/BFT_SY<br />

MP_REPORT.pdf#search=%22pacific%20bluefin%20tuna%22<br />

Miyake, M., Miyabe, N. and Nakano, H. 2004. Historical trends of tuna catches in the world.<br />

FAO Technical; Paper T467. 83 p.

Miyake, P.M. 2005. Factors affecting recent developments in tuna longline fishing capacity and<br />

possible options for management of longline capacity. In: Management of tuna fishing capacity:<br />

conservation and socio-economics (Bayliff, W.H., Leiva moreno, J.I.D., and Majowksi, J. eds.).<br />

Second meeting of the Technical Advisory Committee of the FAO Project, Madrid, Spain,<br />

March 15-18 2004.<br />

Shimose, T., Tanabe, T., Kai, M., Muto, F., Yamasaki, I., Abe, M., Chen, K.S., Hsu, C.C. 2008.<br />

Age and growth of Pacific bluefin tuna, <strong>Thunnus</strong> <strong>orientalis</strong>, validated by the sectioned otolith<br />

ring counts. ISC/08/PBF/01/08.<br />

Shimose, T., Tanabe, T., Chen, K. and Hsu, C. Age determination and growth of Pacific bluefin<br />

tuna, <strong>Thunnus</strong> <strong>orientalis</strong>, off Japan and Taiwan. Fisheries Research 100:134-139.<br />

Tanaka, S. 2006. Maturation of bluefin tuna in the Sea of Japan. ISC PBF-WG/06 Doc 9.7 pp.<br />

Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC). 2007a. Commission vessel<br />

monitoring system. Fourth Regular Session, Conservation and Management Measure 2007-02.<br />

Tumon, Guam, December 2-7, 2007. 4 p.<br />

Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC). 2007b. Conservation and<br />

management measure for the regional observer programme. Fourth Regular Session,<br />

Conservation and Management Measure 2007-01. Tumon, Guam, December 2-7, 2007. 10 p.<br />

Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC). 2008. Conservation and<br />

Management Measure for Northern Pacific Bluefin Tuna. Northern Committee Fourth Regular<br />

Session WCPFC-2008-NC4/DP-01. Tokyo, Japan, September 9-11, 2008. 2 p.<br />

Yamada, H., Matsumoto, T. and Miyabe, N. 2009. Overview of the Pacific bluefin tuna fisheries.<br />

Collective Volume of Scientific Papers 63:195-206. Online: http://www.iccat.int/Documents/CV<br />

SP/CV063_2009/no_1/CVOL63010195.pdf<br />

Yukinawa, M. and Yabuta, Y. 1967. Age and growth of bluefin tuna, <strong>Thunnus</strong> thynnus<br />

(Linnaeus), in the North Pacific Ocean. Nankai Regional Fisheries Research Laboratory Report<br />

25:1-18.