METROPOLIS PRESS BOOK - Kino International

METROPOLIS PRESS BOOK - Kino International

METROPOLIS PRESS BOOK - Kino International

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

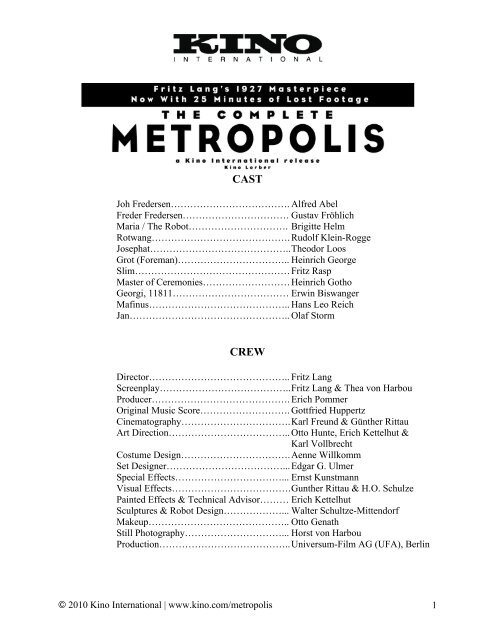

CAST<br />

Joh Fredersen………………………………. Alfred Abel<br />

Freder Fredersen…………………………… Gustav Fröhlich<br />

Maria / The Robot…………………………. Brigitte Helm<br />

Rotwang……………………………………. Rudolf Klein-Rogge<br />

Josephat…………………………………….. Theodor Loos<br />

Grot (Foreman)…………………………….. Heinrich George<br />

Slim………………………………………… Fritz Rasp<br />

Master of Ceremonies……………………… Heinrich Gotho<br />

Georgi, 11811……………………………… Erwin Biswanger<br />

Mafinus…………………………………….. Hans Leo Reich<br />

Jan………………………………………….. Olaf Storm<br />

CREW<br />

Director…………………………………….. Fritz Lang<br />

Screenplay………………………………….. Fritz Lang & Thea von Harbou<br />

Producer……………………………………. Erich Pommer<br />

Original Music Score………………………. Gottfried Huppertz<br />

Cinematography……………………………. Karl Freund & Günther Rittau<br />

Art Direction……………………………….. Otto Hunte, Erich Kettelhut &<br />

Karl Vollbrecht<br />

Costume Design……………………………. Aenne Willkomm<br />

Set Designer………………………………... Edgar G. Ulmer<br />

Special Effects……………………………... Ernst Kunstmann<br />

Visual Effects………………………………. Gunther Rittau & H.O. Schulze<br />

Painted Effects & Technical Advisor……… Erich Kettelhut<br />

Sculptures & Robot Design………………... Walter Schultze-Mittendorf<br />

Makeup…………………………………….. Otto Genath<br />

Still Photography…………………………... Horst von Harbou<br />

Production………………………………….. Universum-Film AG (UFA), Berlin<br />

© 2010 <strong>Kino</strong> <strong>International</strong> | www.kino.com/metropolis 1

SYNOPSIS<br />

(Passages and sections still considered lost are italicized; new additions to this restoration are in bold.)<br />

In Metropolis, a towering city of the future, society is divided into two classes: one of planners and<br />

management, who live high above the Earth in skyscrapers; and one of workers, who live and toil<br />

underground, slaves to the whistle of Metropolis’s ten-hour clock.<br />

Like the other children born into the privileged upper caste, Freder Fredersen, the only son of Metropolis’<br />

ruler, lives a life of luxury. One day, as he and his friends play games in the lush, private Eternal Gardens,<br />

they are interrupted by a beautiful girl, accompanied by a group of workers’ children. They are quickly<br />

ejected, but Freder is transfixed by the girl — and decides to follows her down to the grim Lower City<br />

machine rooms. As he watches, a worker collapses at his station and an enormous machine (known as the<br />

M-Machine) violently explodes and kills dozens of workers. In the smoke, Freder has a vision of the M-<br />

Machine as Moloch, the god of fire, gobbling up chained slaves offered in sacrifice.<br />

Horrified by what he has seen, Freder returns to the New Tower of Babel, a massive skyscraper owned by<br />

his father Joh Fredersen (hereafter referred to as ‘Fredersen’). He confronts his father and describes the<br />

deplorable conditions and horrific accident in the machine room, but Fredersen is more focused on<br />

hearing about the accident from Freder and not from his clerk Josephat — a cold rationality that shocks<br />

Freder. Grot, foreman of the Heart Machine (which produces the needed energy for Metrpolis) informs<br />

Fredersen of papers resembling maps or plans that have been discovered in the dead workers’ pockets.<br />

Furious, Fredersen fires Josaphat and tells his brooding henchman Der Schmale (aka the Thin Man) to<br />

start following his son.<br />

Outside the office, Freder keeps Josaphat from committing suicide and they commiserate together, finally<br />

agreeing to meet later at Josaphat’s place. Returning to the Lower City, Freder takes over for Worker<br />

No. 11811 (known as Georgy), who works a machine that directs electrical power to the enormous series<br />

of elevators in the New Tower of Babel, and has collapsed at his station. They exchange clothes, and<br />

Freder tells Georgy to go to Josaphat’s apartment and to wait for him there. When he reaches<br />

Freder’s car, however, Georgy finds large blocks of money in the pocket of Freder’s pants and<br />

decides to go to Yoshiwara, the city’s red-light district. The Thin Man, meanwhile, records<br />

Georgy’s movements, mistaking him for Freder.<br />

Fredersen, curious about the papers found, decides to consult the scientist Rotwang, an old collaborator<br />

who lives in a house contained in the lower levels of the city. In Rotwang’s inner sanctum, Fredersen<br />

discovers a monument dedicated to Hel, his late wife; though Rotwang loved Hel, she abandoned<br />

him for the wealthy, powerful Fredersen, and died giving birth to their son Freder. Rotwang has<br />

never been able to get over the loss, and is furious when he sees that Fredersen has discovered the<br />

hidden sculpture. After railing against his past rival, Rotwang presents his latest invention: a machine<br />

woman who is to replace his lost Hel. In 24 hours, he tells Fredersen, the machine woman will be<br />

indistinguishable from his dead beloved. Meanwhile, Freder works at Georgy’s machine until he becomes<br />

delirious, having visions of being crucified to the factory clock.<br />

When Fredersen asks Rotwang to help him decipher the papers, Rotwang identifies them as maps to the<br />

2,000-year-old catacombs that are deep under the Lower City. Back in the factory, the shifts change, and<br />

workers take Freder down into the catacombs for their secret meeting. Fredersen and Rotwang follow<br />

their map to the catacombs at the same time. There, the beautiful Maria appears and begins preaching to<br />

the workers (including the disguised Freder) about the Tower of Babel, which was destroyed by the slaves<br />

© 2010 <strong>Kino</strong> <strong>International</strong> | www.kino.com/metropolis 2

that erected it because no common language could be found between them and their rulers. She predicts<br />

the arrival of a mediator who will ease the unspeakable hardships that the workers of Metropolis endure.<br />

Listening to the sermon, Fredersen realizes that Maria is a threat to his authority over the workers.<br />

Rotwang notices Freder in the crowd, but hides this fact from Fredersen. Freder is overcome with his<br />

passion for Maria and for her cause. As the crowd of workers adjourns, Maria recognizes Freder as the<br />

awaited mediator.<br />

Fredersen instructs Rotwang to give his machine woman the appearance of Maria, thus enabling him to<br />

mislead the workers. Rotwang agrees, but has ulterior motives, intending to use the machine-man to ruin<br />

Fredersen’s life. Freder and Maria kiss, and agree to meet the next day at the cathedral in the Upper City.<br />

When Fredersen returns to his offices, Rotwang pursues Maria through the catacombs, terrorizing her<br />

with the beam of his flashlight before abducting her.<br />

The next day, Freder enters the cathedral of Metropolis and listens to the sermon of a monk who declares<br />

that the apocalypse is drawing near and will announce itself in the form of a sinful woman. Back in his<br />

laboratory, Rotwang instructs his new machine woman (the “false Maria”) to destroy Fredersen’s<br />

city and murder his son. As Freder wanders through the cathedral, he finds a group of figures<br />

representing Death and the Seven Deadly Sins.<br />

A bleary-eyed Georgy emerges from Yoshiwara after a long night of pleasure. As he gets into<br />

Freder’s car, he is apprehended by the Thin Man and forced to reveal details of a planned meeting<br />

at Josaphat’s house. After missing Maria at the cathedral, Freder goes to Josaphat’s place so that<br />

Georgy can take him to the Lower City — but he is surprised to learn from Josaphat that Georgy<br />

never showed up.<br />

Freder leaves to continue his search for Maria, but moments later the Thin Man arrives and<br />

discovers Georgy’s cap, further evidence of the link between Freder, Josaphat and Georgy. He tries<br />

to get Josaphat to betray Freder, first through bribery, then through threats and intimidation, and<br />

finally by force. The two men struggle, but the Thin Man is too strong for Josaphat; after defeating<br />

him, he tells Josaphat that he will return for him in three hours.<br />

Freder walks through the streets and hears Maria’s cries as she is overpowered by Rotwang. He follows<br />

the sound to the door of Rotwang’s house — where a further series of doors open for him, trapping him<br />

inside. When Freder demands to know where Maria is, Rotwang tells him that she is with Fredersen. In a<br />

letter, Rotwang invites Fredersen to a demonstration of the false Maria: a dance performance<br />

before the male elite of Metropolis that will prove no one can tell that she is a machine.<br />

In his office, Fredersen ogles the false Maria and instructs her on what to do to sabotage the workers.<br />

Freder discovers the two together, and he collapses at the thought that his beloved has betrayed him with<br />

his father. As Freder languishes in bed, the false Maria beguiles the male elite with an erotic dance; Jan<br />

and Marinus, sons of ruling-class citizens, are entranced — and willing to commit “all seven deadly sins”<br />

for her sake.<br />

The Thin Man keeps watch over the fever-ridden Freder. In a vision, Freder sees him transformed into<br />

the monk who preached about the apocalypse in the cathedral and warned that the appearance of<br />

the whore of Babylon would precede the city’s downfall. When he awakes, he finds the invitation to<br />

the false Maria’s unveiling on his nightstand, where a doctor has carelessly left it. As a nurse tends to<br />

him, Freder has another vision of the cathedral statues of Death and the Seven Deadly Sins coming<br />

toward him, with Death’s scythe sweeping through the sickroom.<br />

© 2010 <strong>Kino</strong> <strong>International</strong> | www.kino.com/metropolis 3

As the elite sons’ response to the false Maria’s licentious dance reaches fever pitch, Josaphat escapes his<br />

confinement and is reunited with Freder. The Thin Man reports to Fredersen about the increasing<br />

unrest in the Lower City, warning that “the only thing keeping the workers in check is their<br />

expectation of getting the mediator promised to them.” Jan is killed in a duel with Marinus over the<br />

false Maria, and the Eternal Gardens become deserted as the privileged sons of Metropolis all gather in<br />

Yoshiwara to vie for the false Maria’s favors, and even more of them die in confrontations with each<br />

other. Josaphat tells Freder that “this woman, at whose feet all sins are heaped, is also named<br />

Maria,” and that it is the same Maria who gives sermons to the workers in the catacombs. The shift<br />

whistle sounds, signaling for the workers to go the catacombs, and Freder tells Josaphat that it is<br />

time for the mediator to appear at last. Freder and Josaphat descend into the Lower City.<br />

Fredersen instructs the Thin Man that the workers should not be stopped, no matter what they decide to<br />

do. He sets off to meet Rotwang, who is still holding the real Maria prisoner. Rotwang explains to her that<br />

the false Maria only seems to follow Fredersen’s orders – when in fact she obeys Rotwang’s will alone.<br />

At the secret meeting in the catacombs, the false Maria urges the workers to rebel and destroy the Lower<br />

City’s machines. When Freder and Josaphat arrive, Freder realizes that the agitator cannot be the real<br />

Maria and cries out. A worker under the false Maria’s rabble-rousing spell identifies Freder as Joh<br />

Fredersen’s son, and the mob of workers attacks Freder and Josaphat. Georgy is stabbed as he shields<br />

Freder with his own body. The workers, led by the false Maria, rush off to destroy the machines, leaving<br />

Georgy to die in Freder and Josaphat’s arms.<br />

Meanwhile, Fredersen has secretly heard what Rotwang has revealed to the real Maria, and he attacks<br />

Rotwang. While the two fight, Maria escapes into the city. Wave after wave of enraged workers<br />

mass at the gates and elevators leading to the machine rooms, and the real Maria follows. The false<br />

Maria and the rioters attack the M-Machine, convincing the workers there to join them — but<br />

when they attempt to move on to the Heart Machine, Grot closes the giant gates. Fredersen, having<br />

defeated Rotwang in their fight, returns to his office and receives a desperate report from Grot over<br />

a videophone. He orders Grot to open the gate and to let things take their course. Grot reluctantly obeys,<br />

but holds the surge of workers at bay with a wrench. As the real Maria draws close, the false Maria<br />

damages the Heart Machine and escapes to the Upper City.<br />

As the Lower City begins to flood from the damage to the Heart Machine, the real Maria sounds the alarm<br />

and gathers the workers’ children, but their escape is cut short by an avalanche of wrecked machine room<br />

elevators. As the water rushes in from all sides and quickly rises around them, they become trapped<br />

and increasingly desperate. Josaphat and Freder finally discover them, but their attempt to reach<br />

safety through the stairwell of the towering airshaft is blocked by a locked steel grille. As countless<br />

children continue to climb into the stairwell, Freder and Josaphat are able to break through the<br />

grille and on to safety as the Lower City is engulfed by flood.<br />

While Fredersen fears for Freder’s safety, Grot crawls from the Heart Machine wreckage and stops the<br />

workers’ victory dance, telling them that their children must have all drowned. The workers blame Maria,<br />

declaring her a witch. Meanwhile, in Yoshiwara, the false Maria urges the dancing crowd out onto the<br />

street, crying: “Let’s watch the world go to hell!” Rotwang, who has survived Fredersen’s attack, regains<br />

consciousness and drags himself to Hel’s monument. With the words, “Now I am going to take you<br />

home, my Hel!,” he sets out to recapture his machine woman.<br />

Freder, Josaphat and Maria find refuge for the children at the Upper City’s Club of the Sons, but<br />

an exhausted Maria briefly pauses to rest outside the club and is separated from the group. At the<br />

same time, Grot leads the riotous workers through the streets — and when they come upon Maria<br />

© 2010 <strong>Kino</strong> <strong>International</strong> | www.kino.com/metropolis 4

outside the club, Grot calls her a witch and declares that she must be burned at the stake. Terrified,<br />

she runs from the menacing workers into the city streets.<br />

As the angry mob of workers and the procession of Yoshiwara revelers collide, Grot mistakenly seizes the<br />

false Maria, and the workers tie her to a stake in front of the cathedral and prepare to burn her. Freder’s<br />

frantic search for “his” Maria brings him to the cathedral, where he fears the real Maria is about to be<br />

burned at the stake. Meanwhile, the real Maria is chased into the cathedral portal by Rotwang, who takes<br />

her for his machine woman and now wants to give her the likeness of Hel after all. Maria flees from him<br />

into the bell tower, where she hangs desperately from the cathedral bell’s massive rope.<br />

As the bell rings, the false Maria is unmasked by the rising flames. When Freder and the workers realize<br />

that they have been tricked, they look up and see Rotwang chasing the real Maria across the cathedral<br />

roof. Freder races into the cathedral and pursues Rotwang and Maria, and he and Rotwang engage in a<br />

fierce fight. Josaphat brings Fredersen to the cathedral square, where he reassures the assembled workers<br />

that their children were rescued. Rotwang carries the real Maria farther up the cathedral roof, but Freder<br />

frees her and Rotwang falls to his death.<br />

Later, the workers gather before the cathedral’s portal. Maria and Freder — the prophet of reconciliation<br />

and the mediator — declare an alliance between the rulers and the ruled. Freder places Fredersen’s hand<br />

in Grot’s and declares that “the mediator between brain and hands must be the heart.”<br />

© 2010 <strong>Kino</strong> <strong>International</strong> | www.kino.com/metropolis 5

ABOUT THE PRODUCTION<br />

In 1924, Germany’s UFA Studios sent their star producer Erich Pommer and star director Fritz Lang to<br />

the gala New York premiere of their two-part mythic spectacle Die Niebelungen. For years, Lang claimed<br />

that he conceived Metropolis (“the glaring lights and the tall buildings”) on this trip, although he and his<br />

co-scenarist (and wife) Thea Von Harbou had already been at work on the concept and scenario for more<br />

than a year at this point. Ultimately, though, it was Lang and Pommer’s whirlwind VIP tour of several<br />

Hollywood film studios on a subsequent leg of their American junket that may have influenced<br />

Metropolis more than anything else. Humbled by the technical superiority and perfect vertical integration<br />

of the studios, it was here that the men realized that their next picture would have to be of a size and<br />

scope that could rival the craftsmanship and spectacle that had become synonymous with American<br />

picture making.<br />

Although UFA’s expansion had stalled due to rampant inflation and a fitful cash flow, Lang immediately<br />

declared his intention to create “the costliest and most ambitious picture ever” — and the studio justified<br />

their investment with the assumption that the film would prove irresistible to US distributors. Fresh from<br />

the triumph of the Niebelungen films, Lang and production designers Otto Hunte and Erich Kettlehut set<br />

about designing a modernist cityscape that encompassed the full range of 1920s architectural and<br />

industrial futurism — as well as a series of settings that were steeped in brooding medieval religiosity. In<br />

every aspect of the design, from Walter Schulze-Mittendorf’s sculptures to Aenne Willkomm’s costumes,<br />

Lang strove to unite the disparate visual motifs and traditions that were contributing to Germany’s<br />

underdog supremacy in the contemporary art world. Karl Freund, UFA’s star cameraman, was tapped to<br />

photograph the film with the same versatility and precision he had shown with the grim romanticism of<br />

The Golem, the relentless experimentation of The Last Laugh, and the breathless pulp of Lang’s own Der<br />

Spione Pt. II.<br />

As detailed in the script, the meticulous miniature photography and full-scale floods, explosions and riots,<br />

necessitated a new level of collaborative ingenuity from every department. Miniature sets were built on a<br />

grand scale in eye-popping forced perspectives, through which stop-frame animated vehicles drove or<br />

flew from building to building. Photographer Eugene Shufftan used a unique new process for combining<br />

live action and miniatures via carefully placed mirrored glass. Over 36,000 extras were used for the live<br />

action flood, the workers’ riots and the Tower of Babel scenes, which were created on UFA’s<br />

Neubabelsberg lot. Future directors Alfred Hitchcock and Billy Wilder were both set visitors and Sergei<br />

Eisenstein made a much-publicized visit to lend his handshake of approval to Lang’s massive struggle.<br />

Though the 35-year-old Lang’s unyielding perfectionism and drive were already the substance of legend<br />

in the German film community, the despotic tenacity he brought to Metropolis surprised even veterans of<br />

his previous films. Newcomers like Gustav Frolich — promoted out of the extras ranks when the actor<br />

originally cast as young Freder was fired, were shocked. “In scenes of physical suffering,” Frolich<br />

remembered years later, “he tormented the actors until they [all] suffer[ed].” Frolich’s co-star Brigitte<br />

Helm, another of Lang’s discoveries, fared worst of all, as Lang badgered the 17-year-old (nicknamed<br />

“the virgin of Neubabelsberg” by the Metropolis crew) through repeated takes, under the most<br />

bewildering assortment of physical deprivations ever devised for a motion picture. “I have to feel you are<br />

inside the robot,” Lang insisted to Helm at one point, as she slowly asphyxiated in the wood and plaster<br />

armor that transformed her into the robotrix Maria.<br />

Managed more like a European builders’ guild than its factory-esque Hollywood counterparts, UFA hired<br />

many key craftsmen by the job rather than as permanent staff — which only added to the studio’s<br />

crippling overhead. As Metropolis’s cameras rolled over 310 shooting days and 60 nights and UFA’s<br />

© 2010 <strong>Kino</strong> <strong>International</strong> | www.kino.com/metropolis 6

coffers emptied, Pommer was summoned before the desperate studio board. They had finally made a deal<br />

with Paramount and Metro (heavily slanted in Paramount’s favor) for US distribution of select UFA<br />

films, but Lang’s excesses were threatening to bankrupt them before they could deliver Metropolis to<br />

their new American partners. The footage Lang was generating was so astounded that the board was<br />

willing to let him off the hook — but Pommer was relieved of his duties on Metropolis and would shortly<br />

depart for America. After 17 months of shooting, Lang completed the film at a cost of 5.3 million marks<br />

— almost four times as much as the film’s original budget of 1.5 million.<br />

RELEASE AND REACTION<br />

Once edited to Lang’s standards, a nearly two-and-a-half-hour-long cut of Metropolis was submitted in<br />

November of 1926 to the German censors, who declared the film “educational” and “artistic” and<br />

approved it for release — but UFA’s new partners at Paramount were less appreciative when shown the<br />

same version a month later. Accustomed to star-driven films with simple plots and an absolute minimum<br />

of symbolic underpinnings, Paramount demanded extensive cuts to bring Metropolis in line with their<br />

idea of audience-friendly entertainment.<br />

The film officially premiered in Berlin (at Lang’s original, un-cut length) on January 19, 1927, and<br />

received decided mixed reviews — the studio’s hysterical publicity had backfired by creating unrealistic<br />

expectations in the press. As the most ambitious and expensive film ever made in Europe, Metropolis<br />

needed to be everything to everyone – and the social, political and artistic tensions of the time meant that<br />

it was evaluated as a barometer of Weimar Germany’s past, present and future, rather than as a movie.<br />

The left wing, appalled at the portrayal of an anger-blinded working class abandoning their children and<br />

destroying their own homes, found the film fascistic. The right wing (along with UFA and Paramount)<br />

was equally disturbed by the destructive revolt of Metropolis’ Lower City denizens, and found the film<br />

borderline Communist. Technocrats saw the film’s industrial nightmare world as being anti-science, and<br />

clergy found its vision of a sex-crazed upper-class killing themselves over a libertine robot both prurient<br />

and reprehensible.<br />

Though UFA briefly ran Metropolis in Berlin and Nuremberg in its original length, the film was soon<br />

pulled from theaters and redone for its US release; Paramount cut the film down from 12 and 7 reels and<br />

hired American playwright Channing Pollock to rewrite the film’s title cards. Much of the symbolism was<br />

removed, as well as the key conflict between Rotwang and Joh Fredersen over Freder’s mother Hel<br />

(Pollock believed that “Hel” was too close to “Hell” to be accepted by American filmgoers), Der<br />

Schlame’s pursuit of Freder, the majority of scenes in the red-light district of Yoshiwara, and the uprising<br />

workers’ extended pursuit of Maria at the end of the film. As a result, Lang’s two narrative strengths —<br />

obsessive romantic fatalism and breathless pulp intrigue — were nearly eliminated, while the story’s<br />

fairly vague, supposedly Socialist content was brought to the forefront. Lang would confess in retirement<br />

that, “I was not so politically minded in those days as I am now.”<br />

This new version of Metropolis — nearly an hour shorter and far less coherent — premiered in the US in<br />

March of 1927 and shortly thereafter in England (in a slightly altered version). Lang bitterly remarked to<br />

British journalists at the time, “I love films so I shall never go to America. Their experts have slashed my<br />

best film…so cruelly that I dare not see it while I am in England.” Though the film was relatively well<br />

reviewed in the US (“a weird and fascinating picture,” opined the New York Herald Tribune), it was<br />

quickly forgotten in the sensation created by the arrival of talking pictures that same year.<br />

But in spite of the relative incoherence of the studio-truncated story, the images of Metropolis would<br />

display a remarkable staying power in the years to come. Pauline Kael eulogized its “moments of<br />

incredible beauty and power,” and declared Metropolis a “beautiful piece of expressionist design.” Even<br />

© 2010 <strong>Kino</strong> <strong>International</strong> | www.kino.com/metropolis 7

Stanley Kubrick confessed that the mad scientist title character of Dr. Strangelove was inspired by<br />

Metropolis’ Rotwang. But the film’s aesthetic reverberations began to be felt most strongly in the<br />

eighties, in the wake of wide-release genre mongrels like Star Wars (featuring the Maria robot look-a-like<br />

C3PO) and Blade Runner (like Metropolis, re-cut by nervous producers at the time of its release).<br />

PREVIOUS RESTORATIONS<br />

From 1927 until the early 1980s, Metropolis was screened in a variety of versions and lengths, but all of<br />

them derived from the general release prints cut by Paramount and UFA. (Between 1968 and 1972, the<br />

East German Film Archive compiled a version of the film with the help of other world archives, but most<br />

of the riddles of the film’s abridged narration could not be solved, due to a lack of secondary sources or<br />

original script.)<br />

In 1984, the rights to the film were licensed to composer Giorgio Moroder, who put together a “pop”<br />

version by re-cutting shots and replacing missing stills with a montage of stills. Even though this version<br />

used few intertitles, included subtitles and added color tints to the film, none of these elements were more<br />

controversial than its newly composed score, which featured songs by Queen’s Freddy Mercury, Bonnie<br />

Tyler and Jon Anderson. Nevertheless, this version proved to be successful both in theatres and on video,<br />

making the film available to a much larger — and younger — audience.<br />

In 1987, Enno Patalas and the Munich Film Archive took advance of a series of unusual acquisitions to<br />

unveil a third version of Metropolis, now with the historical commitment of making a definitive assembly<br />

of all the known footage. This new version made extensive use of materials acquired from the estate of<br />

composer Gottfried Huppertz — including the original censorship cards (required copies of all the<br />

original intertitles, kept by German censors in the 20s) — as well as newly acquired stills that<br />

documented some of the lost scenes.<br />

Between 1998 and 2002, film preservationist Martin Koeber meticulously compiled a “definitive”<br />

restoration based on the 1987 “Munich” version, working under the auspices of the Friedrich-Wilhelm-<br />

Murnau-Stiftung (the film’s copyright holders, hereafter referred to as the Murnau Foundation) and a<br />

consortium of German archives headed by the German Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv. Using a nitrate original<br />

camera negative found at the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv and original nitrate prints from the British Film<br />

Institute, the George Eastman House and the Fondazione Cineteca Italiana, this new Metropolis was<br />

reconstructed directly from original elements, with new digital technology used to “clean” every frame of<br />

the film. A handful of recovered shots were added, along with newly translated English subtitles, newly<br />

written intertitles with detailed information on still-missing scenes, and a re-recording of the original<br />

score by a sixty-piece orchestra. At 124 minutes, this version was 3,640 feet longer than Moroder’s and<br />

1,320 feet longer than the “Munich” restoration – the most accurate and definitive version of Metropolis<br />

than contemporary audiences could ever expect to see.<br />

THE “COMPLETE” <strong>METROPOLIS</strong><br />

In July 2008, it was announced that an essentially complete copy of Metropolis had been found — a<br />

16mm dupe negative unearthed by the curator of the Buenos Aires Museo del Cine that was considerably<br />

longer than any existing print. It included not merely a few additional snippets, but 25 minutes of “lost”<br />

footage, about a fifth of the film, that had not been seen since its Berlin debut. The discovery of such a<br />

significant amount of material called for yet another restoration, spearheaded again by the Murnau<br />

Foundation and coordinated by their Film Restorer Anke Wilkening. Also returning was Martin Koeber,<br />

Film Department Curator of the Deutsche Kinemathek, who had supervised the 2001 restoration.<br />

© 2010 <strong>Kino</strong> <strong>International</strong> | www.kino.com/metropolis 8

“We discussed the new approach with experts and German archive partners to establish a team for the<br />

2010 restoration,” Wilkening explains. “The project consisted of two main tasks: the reconstruction of the<br />

original cut and the digital restoration of the heavily damaged images from the Argentinian source.”<br />

As word spread of the discovery of the Buenos Aires negative, a nervous public worried that archival<br />

politics might hinder the integration of the rediscovered footage into Metropolis. According to Koerber,<br />

this was never the case: “They were always willing to cooperate; in fact, they offered the material once<br />

they identified what it was.”<br />

Once obtained by the Murnau Foundation, the 16mm negative was digitally scanned in 2K by The Arri<br />

Group in Munich. The condition of the negative — a “back-up” copy made from the original 35mm<br />

nitrate print, which was probably destroyed due to the flammability and chemical instability of the film<br />

stock — posed a major technical challenge to the team, as the image was streaked with scratches and<br />

plagued by flickering brightness. “If we could have had access to the 35mm nitrate print that was<br />

destroyed after being reprinted for safety onto the 16mm dupe negative some 30 years ago, we would<br />

have been able to make a much better copy today,” emphasizes Koeber.<br />

Fortunately, advances in digital technology allowed the team to at least diminish some of the printed-in<br />

wear. “If we…had the Argentinian material for the 2001 restoration, it would have hardly been possible to<br />

work on the severe damage,” Wilkening says. In 2010, however, “it was possible to reduce the scratches<br />

prominent all over the image and almost eliminate the flicker that was caused by oil on the surface of the<br />

original print — [all] without aggressively manipulating the image.”<br />

Under Wilkening and Koerber’s supervision, the visual cleanup was performed by Alpha-Omega Digital<br />

GmbH, utilizing digital restoration software of their own development. “[Digital technology] has made<br />

things possible we could only dream of a decade or two ago,” Koerber says, “Digital techniques allow<br />

more precise interventions than ever before. And it is still evolving — we are only at the beginning.”<br />

Viewing Metropolis today, the Argentine footage is clearly identifiable because so much of the damage<br />

remains. The unintended benefit is that it provides convenient earmarks to the recently reintegrated<br />

scenes. “The work on the restoration teaches us once more that no restoration is ever definitive,” says<br />

Wilkening. “Even if we are allowed for the first time to come as close to the first release as ever before,<br />

the new version will still remain an approach. The rediscovered sections, which change the film’s<br />

composition, will at the same time always be recognizable…as those parts that had been lost for 80<br />

years.”<br />

Other changes are not so noticeable. Because the Buenos Aires negative provided a definite blueprint to<br />

the cutting of Metropolis — which in the past had been a matter of conjecture — the order of some of the<br />

existing shots has been altered in the 2010 edition, bringing Metropolis several steps closer to its original<br />

form.<br />

It is important to note that the “new” shots are not merely extensions of previously existing scenes; in<br />

some cases, they comprise whole subplots that were lopped off in their entirety. (“It restores the original<br />

editing,” Koerber says, “restoring the balance between the characters and subplots that remained and<br />

those that were excised.”) Furthermore, the film’s structure has changed significantly, especially in<br />

regards to Josaphat, Georgy and Der Schmale (the Thin One) — major supporting characters whose roles<br />

had been significantly diminished with the elimination of two extended scenes. “Parallel editing now<br />

becomes a major player in Metropolis,” Wilkening says. “The new version represents a Fritz Lang film<br />

where we can observe the tension between his preferred subject, the male melodrama, and the bombastic<br />

dimensions of the UFA production.”<br />

© 2010 <strong>Kino</strong> <strong>International</strong> | www.kino.com/metropolis 9

From conception to completion, the restoration took about one year, and was performed at a cost of<br />

600,000€ (approx. $840,000). But Wilkening is quick to point out that it is just the latest chapter in an<br />

ongoing saga — as well as a tribute to the other preservationists who have so vigorously championed the<br />

film: “Metropolis is the prototype of an archive film. Decades of research for the lost scenes and various<br />

attempts to reconstruct the first release version have produced a large pool of knowledge of this film.”<br />

Asked how the Metropolis restoration compared to other projects in which the Deutsche Kinemathek<br />

participated, Koerber replies, “No comparison, Metropolis is more complex in many ways. On the other<br />

hand, it is also more rewarding, as the [availability of source material] — film material as well as<br />

secondary sources — is exceptionally good.”<br />

FRITZ LANG (DIRECTOR)<br />

Page 10 of 14<br />

CAST AND CREW BIOS<br />

While the exact origins of film noir are impossible to pinpoint, no director worked within the genre more<br />

consistently or more brilliantly than Fritz Lang. Bringing to the screen an obsessive and fatalistic world<br />

populated by a rogues' gallery of strange and twisted characters, Lang staked out a uniquely hostile corner<br />

of the cinematic universe; despair, isolation, helplessness -- all found refuge in the shadows of his work.<br />

A product of German Expressionist thought, he explored humanity at its lowest ebb, with a distinctively<br />

rich and bold visual sensibility that virtually defined film noir long before the term was even coined.<br />

Born Friedrich Christian Anton Lang in Vienna, Austria, on December 5, 1890, he initially studied to<br />

become an artist and architect, later serving in the Austrian army during World War I and earning an<br />

honorable discharge after being wounded four times. He first entered the German film industry as a<br />

writer, penning a series of horror movies and thrillers beginning with 1917's Hilde Warren Und Der Tod.<br />

In 1919, he and director Robert Wiene teamed up on the script of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and<br />

although Lang exited in the pre-production stages to begin work on another project, his major<br />

contribution to the story -- a framing device ultimately revealing the story line to have been a dream --<br />

went on to rank among the most imitated structural techniques in history.<br />

As a director, Lang debuted in 1919 with the now-lost Halbblut. Upon completing 1920's two-part The<br />

Spiders, his early rise to fame culminated with 1922's Doktor Mabuse der Spieler, which marked the full<br />

emergence of his striking Expressionist aesthetic and introduced his popular Mabuse character. Another<br />

two-part epic, Die Niebelungen, followed two years later, and in 1927 he filmed the science fiction<br />

landmark Metropolis. Lang's transition from the silents to sound began with his masterpiece M (1931).<br />

Written by wife Thea von Harbou, as were most of his principal films of the era, M documented the<br />

crimes of a deranged serial killer (Peter Lorre) preying on the children of Berlin. The film went on to<br />

become a tremendous influence on the work of filmmakers including Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell,<br />

and Jacques Tourneur.<br />

The success of M positioned Lang as a leading figure of the German film industry, but its power may<br />

have been too great -- Nazi propagandist Josef Goebbels offered Lang the opportunity to direct films for<br />

Adolf Hitler, unaware of the director's own Jewish heritage. According to legend, Lang -- already stinging<br />

from a government ban on his recent Die Testament des Dr. Mabuse -- fled the country that same<br />

evening, leaving without the pro-Nazi von Harbou. After briefly stopping in France to shoot Liliom, he<br />

landed in Hollywood, earning immediate acclaim with 1936's Fury, a stinging indictment of mob<br />

mentality.<br />

© 2010 <strong>Kino</strong> <strong>International</strong> | www.kino.com/metropolis 10

Lang spent the next several decades in America working in a variety of styles and genres, including the<br />

Western (among his more notable efforts being 1940's The Return of Frank James and 1952's Rancho<br />

Notorious). However, his greatest achievement during the period was a series of grim thrillers which went<br />

far in defining the look and texture of film noir; pictures like 1944's Ministry of Fear and The Woman in<br />

the Window, 1945's Scarlet Street, 1953's The Big Heat, and 1956's While the City Sleeps offered bleak,<br />

gripping depictions of life on the cliff's edge of desperation, exploring recurring themes of obsession,<br />

vengeance, and persecution in haunting detail.<br />

However, by the mid-'50s, Lang had become disenchanted with the Hollywood system, and after<br />

completing 1956's superb Beyond a Reasonable Doubt, he briefly stopped in India to film 1958's Die<br />

Tiger von Eschnapur before returning to Germany after an absence of decades. Upon completing 1959's<br />

Indische Grabmal, he directed one last Mabuse picture, Tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse, before<br />

announcing his retirement from filmmaking. After appearing in Jean-Luc Godard's 1963 feature Contempt<br />

as himself, Lang returned to America to live out his remaining years. He died in Los Angeles on August<br />

2, 1976. (written by Jason Ankeny for the All Movie Guide)<br />

KARL FREUND (CINEMATOGRAPHER)<br />

Karl Freund was a photographer who made notable -- and notably enduring -- contributions to<br />

cinematography across a career lasting over 50 years, from the peak of the silent era into the days of<br />

widescreen theaters, and in television as well as motion pictures. Additionally, he directed several movies<br />

during the 1930s that were notable for their visual style, including two recognized horror classics: The<br />

Mummy (1932) and Mad Love (1935).<br />

Freund was born in Koniginhof, Bohemia, in what later became Czechoslovakia (now the Czech<br />

Republic), in 1890. He entered the film industry as a projectionist in 1907, but his interests lay in the<br />

other end of the business and the lens, and a year later he joined the Berlin branch of Pathé Films as a<br />

newsreel cameraman. Six years later, he joined Germany's Universum Film Aktiengesellschaft (UFA),<br />

and was involved with such notable productions as Richard Oswald's The Arc (1919), during which he<br />

met the actress Gertrude Hoffman, who would become his wife. That same year, Freund worked for the<br />

first time with directors Fritz Lang (Spiders, Part 1), Ernst Lubitsch (Rausch), and F.W. Murnau (The<br />

Blue Boy, aka Emerald of Death). All of these films were well photographed, but there were a handful on<br />

which he distinguished himself sufficiently to begin attracting an international reputation -- among them<br />

were Der Golem (1920), co-directed by Carl Boese and Paul Wegener, and Murnau's The Last Laugh<br />

(1924). The latter, with its highly mobile camera, and the distinctive uses of distorted lenses and panfocus<br />

effects, demonstrated a visual language more sophisticated than any yet seen in cinema, and<br />

brought Freund himself nearly as much attention in the industry as it did the director.<br />

Freund also made a unique contribution to the visual style of Walter Ruttmann's Berlin: Symphony of a<br />

Great City (1927); but it was somewhat overshadowed by his work during that same period on a movie<br />

that would overwhelm much of the cinematic world with its impact, visual and thematic: Fritz Lang's<br />

Metropolis. Freund's contribution to the movie's success was immense, many of its visuals and its overall<br />

look so striking that its impact across the decades that followed only seemed to increase with time, this<br />

despite the fact that it was not that big a success at the box office in 1927-1928. Metropolis marked the<br />

culmination of Freund's work in silent films, but it was only the end of the beginning of his career, and<br />

prelude to a period of much greater influence on cinema and his profession.<br />

The coming of sound only enhanced Freund's career and reputation, thanks to his fascination with<br />

technical innovation. He was among the very first cinematographers to work with sprocketed magnetic<br />

tape as a sound medium, which became the standard means of shooting sound film for the next 60 years.<br />

He was also involved with experimental color film shooting in England at the end of the 1920s. He might<br />

© 2010 <strong>Kino</strong> <strong>International</strong> | www.kino.com/metropolis 11

well have made his career in England, but Hollywood beckoned -- in 1930, he was signed to Universal.<br />

Over the next two years, he busied himself photographing such movies as Tod Browning's Dracula<br />

(1931), John M. Stahl's Strictly Dishonorable (1931), and Robert Florey's Murders in the Rue Morgue<br />

(1932). That same year, he made an official return to the director's chair on The Mummy (1932), starring<br />

Boris Karloff and Zita Johann – followed shortly thereafter by the musical romp Moonlight and Pretzels<br />

(1933). Freund's remaining directorial credits were confined to the next two years of his career, and<br />

showed him ranging freely between drama, light romantic comedy, and horror, closing out his director's<br />

career in the latter genre with Mad Love (1935), starring Peter Lorre.<br />

By that point, Freund had moved to MGM, where he contributed to numerous films, often in very<br />

specialized sequences such as the rooftop production numbers in The Great Ziegfeld (1936). He<br />

photographed such classics as The Good Earth (1937, for which he won an Oscar) and Golden Boy<br />

(1939), the latter at Columbia Pictures under director Rouben Mamoulian. He remained busy at MGM<br />

throughout the war, working on some of the studio's most prestigious productions, including Tortilla Flat<br />

(1942), A Guy Named Joe (1943), and The Thin Man Goes Home (1944). In 1942, he managed to get<br />

parallel Oscar nominations, for The Chocolate Soldier and Blossoms in the Dust, in the black-and-white<br />

and color categories, respectively. He moved to Warner Bros. in the late '40s, where his work included<br />

John Huston's Key Largo (1948) and Michael Curtiz's Bright Leaf (1950). Freund closed out his movie<br />

career by photographing Montana (1950), starring Errol Flynn.<br />

Freund's professional work was far from over, however -- he simply saw challenges that transcended<br />

anything he could do tied to a single studio, especially with the studios seemingly entering a period of<br />

decline after World War II. In 1944, Freund had founded the Photo Research Corporation, which, among<br />

other achievements, developed the Norwich incident light meter. He continued working on innovations in<br />

his field, and in 1951, he found a new challenge in a new medium of television. He was approached by<br />

Desilu, a new television production company founded by the married acting couple of Desi Arnaz and<br />

Lucille Ball, who were about to embark on a situation comedy series of their own. It was here that Freund<br />

developed what became known as the three-camera method for shooting a television program on film in<br />

an affordable way. I Love Lucy, when it went on the air, was the best-looking series ever seen on<br />

television up to that time, and the process subsequently became the standard method of shooting series.<br />

In 1955, Freund’s work at Photo Research Corp. was honored with a special technical award from the<br />

Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences. In 1960, after a decade as the most important and<br />

influential photographer in television, Freund retired at the age of 70, though he continued to work at<br />

Photo Research well into the 1960s. He passed away in 1969 at the age of 79 in Santa Monica, CA.<br />

(written by Bruce Eder for the All Movie Guide)<br />

THEA VON HARBOU (SCREENWRITER) was already a successful screenwriter, novelist and<br />

journalist by the time she was introduced to Lang in 1920. Born into an aristocratic Prussian family, her<br />

first novels focused on epic national myths and legends and were popular source material for the nascent<br />

German film industry. Introduced to Lang by producer-director Joe May, the two collaborated on the<br />

script to his The Wandering Image, and married after Lang’s wife committed suicide in late 1920. From<br />

then on, they shared writing credit on every one of Lang’s pre-war German films.<br />

In the 30s, Von Harbou was drawn to Nazism, and stayed in Germany and divorced Lang as soon as he<br />

left in 1933. She spent World War II working in the Nazi-controlled Germany film industry, and was<br />

arrested, interrogated and briefly interred by the allies after the war. She died in 1954.<br />

GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ (COMPOSER) made his living as a singer and stage actor before he was<br />

introduced to Lang by Rudolf Klein-Rogge, who played Rotwang in Metropolis. His first original film<br />

score was for Lang’s Die Nibelungen; while working on Metropolis, he also composed a score for Zur<br />

© 2010 <strong>Kino</strong> <strong>International</strong> | www.kino.com/metropolis 12

Chronik Von Grieshuus. Though he continued composing songs and scoring films until his death in 1937,<br />

virtually none have survived or are available on record.<br />

OTTO HUNTE (ART DIRECTOR) was one of the greatest art directors of the German Expressionist<br />

period. As Lang's primary designer, Hunte brought his experience as a painter to the director’s<br />

architectural background, translating Lang and Von Harbou’s ideas into the landscapes and constructions<br />

of Die Nibelungen, Metropolis, The Girl in the Moon and the Mabuse films. (In addition to his work with<br />

Lang, Hunte is best known for his collaborations with Georg Wilhelm Pabst on The Love of Jeanne Ney<br />

and with Josef von Sternberg on The Blue Angel.) When Lang left for America, Hunte remained in<br />

Germany, working with Von Harbou on many of her films and even designing the notoriously antisemitic<br />

Jud Süss. After the war, however, he was equally amenable to working with Wolfgang Staudte on<br />

the impressive anti-Nazi film Die Mörder sind unter un. He continued working until his death in 1960.<br />

ERICH KETTELHUT (ART DIRECTOR) collaborated with Lang on Dr. Mabuse the Gambler and<br />

Die Nibelungen before his work on Metropolis. His specialty was architectural models, and he worked<br />

mainly with Guther Rittau, a cameraman with a great interest in special effects. He remained in demand<br />

as a set designer after World War II, but moved from cinema to television after The Thousand Eyes of Dr.<br />

Mabuse, his final collaboration with Lang.<br />

EDGAR G. ULMER (SET DESIGNER) got his start working on the set design of Paul Wegener’s The<br />

Golem and assisting F.W. Murnau on The Last Laugh, for which he devised the first ever tracking shot.<br />

After designing sets for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, G.W. Pabst's The Joyless Street, and three films<br />

(Metropolis, Die Nibelungen, and Spies) for Lang, he invented the new post of Production Designer on M<br />

– a job that entailed designing sets in perspective from each new camera angle. After fleeing from the<br />

burgeoning Nazi regime in Germany, Ulmer came to Hollywood to work as an art director for Erich von<br />

Stroheim, but was soon studying under William Wyler to become a director in his own right. The high<br />

point of his directorial career at Universal was 1934’s The Black Cat, starring Boris Karloff and Bela<br />

Lugosi.<br />

ERICH POMMER (PRODUCER) was one of the most important figures in the German Expressionist<br />

film movement, serving as the head of production at UFA from 1924 to 1926, where he was responsible<br />

for many of the best-known films of the era, including The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, The Last Laugh, The<br />

Blue Angel, Die Nibelungen and Metropolis. His unique combination of artistic commitment, in-thetrenches<br />

production savvy and commercial instinct yielded memorable collaborations with directors<br />

throughout Europe and the United States, including Fritz Lang, F.W. Murnau, E.A. Dupont, Max Ophuls,<br />

Josef Von Sternberg, Robert Weine, Robert Siodmak and Alfred Hitchcock.<br />

ALFRED ABEL (JOH FREDERSEN) appeared in over 140 silent and sound films between 1913 and<br />

1938. He was especially renowned for his avoidance of dramatic gesturing, and learned to show the<br />

psychology and internal tensions of his characters with reserved expressions. After the advent of talkies,<br />

Abel worked with directors such as Detlef Sierk, Anatole Litvak, and Paul Martin; his final film role was<br />

as Daffinger in Herbert Maisch’s Frau Sylvelin (1938), which was not released until after his death in<br />

1937.<br />

GUSTAV FRÖHLICH (FREDER FREDERSON) had played secondary roles in a number of films and<br />

plays before being cast in a small role in Metropolis; when the original leading man, André Mattoni,<br />

walked off the set during shooting, Lang’s wife Thea Von Harbou found Frölich working on set and<br />

immediately cast him as Freder because of his striking good looks. Although typecast after Metropolis as<br />

(in his words) the “nice, naïve boy next door,” Frölich contributed memorable performances in Joe May’s<br />

Heimkehr and Asphalt, Robert Siodmak’s Vorunter-Suchung and Max Ophuls’s Die Verliebte Firma.<br />

© 2010 <strong>Kino</strong> <strong>International</strong> | www.kino.com/metropolis 13

After the war, he worked as a film director and continued to act in film, television and theater until the<br />

80s.<br />

BRIGETTE HELM (MARIA / THE ROBOT) was 17 when she won her dual role in Metropolis, after<br />

photographs sent from her mother resulted in an invite to Lang’s Die Nibelungen set. Although she was<br />

never entirely comfortable with her acting career, she continued to appear in films for UFA (including<br />

The Love of Jeanne Ney) until the mid-30s, when she was finally let out of her contract.<br />

RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE (ROTWANG) started appearing in films in 1919, after a career as an<br />

operatic stage star. His greatest roles were in Lang’s silent films, in which he played the master criminal<br />

Dr. Mabuse, the despotic King Etzel in Die Niebelungen, the megalomaniac Rotwang in Metropolis and<br />

the criminal mastermind Haghi in Spies. His first marriage was to Thea von Harbou, who eventually left<br />

him to marry Lang.<br />

THEODOR LOOS (JOSEPHAT) was a stage actor who also appeared in more than 170 feature films,<br />

including Lang’s Die Niebelungen, M and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse.<br />

HEINRICH GEORGE (GROT) rose to stardom as a complex character actor in the Berlin Theatre.<br />

After Metropolis, he appeared in the first film version of Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz; he also<br />

acted in a number of propaganda films before and after the war. A Nazi sympathizer, he was arrested by<br />

the Soviets after the war and died in an internment camp.<br />

FRITZ RASP (THE THIN ONE) appeared in 104 films between 1916 and 1976; besides Metropolis,<br />

his most notable role was as J.J. Peachum in The Threepenny Opera. Many of his scenes in Metropolis<br />

are part of this new restoration.<br />

© 2010 <strong>Kino</strong> <strong>International</strong> | www.kino.com/metropolis 14