A Case Study of Obligatory Object Fronting in Mandarin Chinese

A Case Study of Obligatory Object Fronting in Mandarin Chinese

A Case Study of Obligatory Object Fronting in Mandarin Chinese

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Pei-Jung Kuo (National Chiayi University)<br />

domo@mail.ncyu.edu.tw<br />

A <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Study</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Obligatory</strong> <strong>Object</strong> <strong>Front<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Mandar<strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>ese<br />

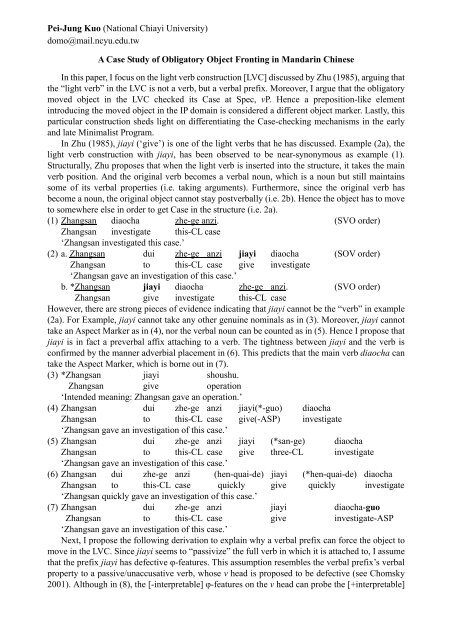

In this paper, I focus on the light verb construction [LVC] discussed by Zhu (1985), argu<strong>in</strong>g that<br />

the “light verb” <strong>in</strong> the LVC is not a verb, but a verbal prefix. Moreover, I argue that the obligatory<br />

moved object <strong>in</strong> the LVC checked its <strong>Case</strong> at Spec, vP. Hence a preposition-like element<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g the moved object <strong>in</strong> the IP doma<strong>in</strong> is considered a different object marker. Lastly, this<br />

particular construction sheds light on differentiat<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Case</strong>-check<strong>in</strong>g mechanisms <strong>in</strong> the early<br />

and late M<strong>in</strong>imalist Program.<br />

In Zhu (1985), jiayi (‘give’) is one <strong>of</strong> the light verbs that he has discussed. Example (2a), the<br />

light verb construction with jiayi, has been observed to be near-synonymous as example (1).<br />

Structurally, Zhu proposes that when the light verb is <strong>in</strong>serted <strong>in</strong>to the structure, it takes the ma<strong>in</strong><br />

verb position. And the orig<strong>in</strong>al verb becomes a verbal noun, which is a noun but still ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s<br />

some <strong>of</strong> its verbal properties (i.e. tak<strong>in</strong>g arguments). Furthermore, s<strong>in</strong>ce the orig<strong>in</strong>al verb has<br />

become a noun, the orig<strong>in</strong>al object cannot stay postverbally (i.e. 2b). Hence the object has to move<br />

to somewhere else <strong>in</strong> order to get <strong>Case</strong> <strong>in</strong> the structure (i.e. 2a).<br />

(1) Zhangsan diaocha zhe-ge anzi. (SVO order)<br />

Zhangsan <strong>in</strong>vestigate this-CL case<br />

‘Zhangsan <strong>in</strong>vestigated this case.’<br />

(2) a. Zhangsan dui zhe-ge anzi jiayi diaocha (SOV order)<br />

Zhangsan to this-CL case give <strong>in</strong>vestigate<br />

‘Zhangsan gave an <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>of</strong> this case.’<br />

b. *Zhangsan jiayi diaocha zhe-ge anzi. (SVO order)<br />

Zhangsan give <strong>in</strong>vestigate this-CL case<br />

However, there are strong pieces <strong>of</strong> evidence <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that jiayi cannot be the “verb” <strong>in</strong> example<br />

(2a). For Example, jiayi cannot take any other genu<strong>in</strong>e nom<strong>in</strong>als as <strong>in</strong> (3). Moreover, jiayi cannot<br />

take an Aspect Marker as <strong>in</strong> (4), nor the verbal noun can be counted as <strong>in</strong> (5). Hence I propose that<br />

jiayi is <strong>in</strong> fact a preverbal affix attach<strong>in</strong>g to a verb. The tightness between jiayi and the verb is<br />

confirmed by the manner adverbial placement <strong>in</strong> (6). This predicts that the ma<strong>in</strong> verb diaocha can<br />

take the Aspect Marker, which is borne out <strong>in</strong> (7).<br />

(3) *Zhangsan jiayi shoushu.<br />

Zhangsan give operation<br />

‘Intended mean<strong>in</strong>g: Zhangsan gave an operation.’<br />

(4) Zhangsan dui zhe-ge anzi jiayi(*-guo) diaocha<br />

Zhangsan to this-CL case give(-ASP) <strong>in</strong>vestigate<br />

‘Zhangsan gave an <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>of</strong> this case.’<br />

(5) Zhangsan dui zhe-ge anzi jiayi (*san-ge) diaocha<br />

Zhangsan to this-CL case give three-CL <strong>in</strong>vestigate<br />

‘Zhangsan gave an <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>of</strong> this case.’<br />

(6) Zhangsan dui zhe-ge anzi (hen-quai-de) jiayi (*hen-quai-de) diaocha<br />

Zhangsan to this-CL case quickly give quickly <strong>in</strong>vestigate<br />

‘Zhangsan quickly gave an <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>of</strong> this case.’<br />

(7) Zhangsan dui zhe-ge anzi jiayi diaocha-guo<br />

Zhangsan to this-CL case give <strong>in</strong>vestigate-ASP<br />

‘Zhangsan gave an <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>of</strong> this case.’<br />

Next, I propose the follow<strong>in</strong>g derivation to expla<strong>in</strong> why a verbal prefix can force the object to<br />

move <strong>in</strong> the LVC. S<strong>in</strong>ce jiayi seems to “passivize” the full verb <strong>in</strong> which it is attached to, I assume<br />

that the prefix jiayi has defective φ-features. This assumption resembles the verbal prefix’s verbal<br />

property to a passive/unaccusative verb, whose v head is proposed to be defective (see Chomsky<br />

2001). Although <strong>in</strong> (8), the [-<strong>in</strong>terpretable] φ-features on the v head can probe the [+<strong>in</strong>terpretable]

φ-features on the object as <strong>in</strong> a SVO counterpart, the defective φ-features on the prefix jiayi causes<br />

the <strong>in</strong>tervention effect (see Chomsky 2000).<br />

(8) [ vP v [ VP jiayi <strong>in</strong>vestigate [ NP this case ]]]<br />

uφ defective φ iφ, uC<br />

In order for the [-<strong>in</strong>terpretable] <strong>Case</strong> feature to be specified/valued, the object has to move to Spec<br />

vP (follow<strong>in</strong>g the Activation Condition by Bošković 2007). The moved object then can check the<br />

[-<strong>in</strong>terpretable] φ-features on the v head via Spec-Head agreement. In this way, the [-<strong>in</strong>terpretable]<br />

<strong>Case</strong>-feature <strong>of</strong> the object can also be specified/checked, as illustrated <strong>in</strong> (9).<br />

(9) [ vP [ NP this case ] v [ VP jiayi <strong>in</strong>vestigate ]]<br />

iφ, uC uφ defective φ<br />

The proposed overt <strong>Object</strong> <strong>Case</strong>-check<strong>in</strong>g derivation has the follow<strong>in</strong>g consequences: Firstly,<br />

the preposition-like element dui <strong>in</strong> (2) cannot be <strong>Case</strong>-relevant like a regular preposition. Paris<br />

(1979) argues that regular PPs <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>ese cannot precede modals or negation. However, it is<br />

possible to have the dui-this case phrase before modals or negation, as <strong>in</strong> (10). This <strong>in</strong>dicates that<br />

the preposition-like element dui is not a real preposition and the whole dui phrase should be <strong>in</strong> the<br />

IP-doma<strong>in</strong>.<br />

(10) Zhangsan [dui zhe-ge anzi] y<strong>in</strong>ggai/meiyou jiayi diaocha.<br />

Zhangsan to this-CL case should/not give <strong>in</strong>vestigate<br />

‘Zhangsan should/did not give an <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>of</strong> this case.’<br />

Follow<strong>in</strong>g Rodríguez-Mondoñedo (2007)’s proposal for Spanish a which is obligatory for<br />

[+person] objects but is absent for [-person] objects, I propose that dui is a differential object<br />

marker [DOM] <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>ese. Yang and van Bergen (2007) have proposed that BA is a DOM <strong>in</strong><br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>ese, too. A BA counterpart for the LVC is shown <strong>in</strong> (11). Moreover, both DOMs are sensitive<br />

to [+person] nom<strong>in</strong>als. If the nom<strong>in</strong>al is [+person], the DOMs dui and BA cannot be omitted, as <strong>in</strong><br />

(12) and (13). If the fronted objects are [-person], the DOMs can be omitted.<br />

(11) Zhangsan [ba zhe-ge anzi] jiayi diaocha<br />

Zhangsan BA this-CL case give <strong>in</strong>vestigate<br />

‘Zhangsan gave an <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>of</strong> this case.’<br />

(12) Zhangsan [*(dui) Lisi] / [(dui) zhe-ge anzi] jiayi diaocha.<br />

Zhangsan to Lisi to this-CL case give <strong>in</strong>vestigate<br />

‘Zhangsan gave an <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>of</strong> Lisi/this case.’<br />

(13) Zhangsan [*(ba) Lisi] / [(ba) zhe-ge anzi ] jiayi diaocha<br />

Zhangsan BA Lisi BA this-CL case give <strong>in</strong>vestigate<br />

‘Zhangsan gave an <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>of</strong> Lisi/this case.’<br />

In addition, the must-move <strong>Object</strong> cannot be well expla<strong>in</strong>ed by the early M<strong>in</strong>imalist Program <strong>in</strong><br />

which Accusative <strong>Case</strong> is checked at Spec, vP. One has to postulate a strong <strong>Case</strong> feature on the<br />

<strong>Object</strong> only <strong>in</strong> the LVC, but not <strong>in</strong> a regular SVO sentence. It is also not possible for jiayi to have an<br />

EPP-like feature s<strong>in</strong>ce it attaches to the verb and whatever is triggered moves to Spec, VP, not Spec,<br />

vP. Mov<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to Spec, VP first violates the Anti-locality Condition (Abels 2003). Compare to other<br />

overt Nom<strong>in</strong>ative <strong>Case</strong>-check<strong>in</strong>g cases such as short passive and rais<strong>in</strong>g construction <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>ese<br />

which may be triggered overtly by the EPP feature on I, the overt <strong>Object</strong> <strong>Case</strong>-check<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the LVC<br />

rema<strong>in</strong>s a puzzle <strong>in</strong> the early M<strong>in</strong>imalist Program.<br />

Selected References: Abels, K. 2003. Successive cyclicity, anti-locality, and adposition strand<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

UConn Doctoral Dissertation./Bošković, Ž. 2007. On the locality and motivation <strong>of</strong> Move and<br />

Agree: An even more m<strong>in</strong>imal theory. LI 38: 589-644./Paris, M.-C. 1979. Some Aspects <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Syntax and semantics <strong>of</strong> the lian…ye/dou Construction <strong>in</strong> Mandar<strong>in</strong>. In S.-H. Teng (Eds.),<br />

Read<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>ese Transformational Syntax. Taipei: The Crane Publish<strong>in</strong>g<br />

co./Rodríguez-Mondoñedo, M. 2007. The Syntax <strong>of</strong> <strong>Object</strong>s: Agree and Differential <strong>Object</strong><br />

Mark<strong>in</strong>g. UConn Doctoral Dissertation./Yang, N. and G. van Bergen. 2007. Scrambled objects and<br />

case mark<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Mandar<strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>ese. L<strong>in</strong>gua 117.9: 1617-1653./Zhu D. 1985. Selected Papers <strong>of</strong><br />

Zhu, DeXi: The first Volume. ShangWu publishers: Beij<strong>in</strong>g.