Volume 3 Number 2 Hegemony and Resistance in the Asia-Pacific

Volume 3 Number 2 Hegemony and Resistance in the Asia-Pacific

Volume 3 Number 2 Hegemony and Resistance in the Asia-Pacific

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

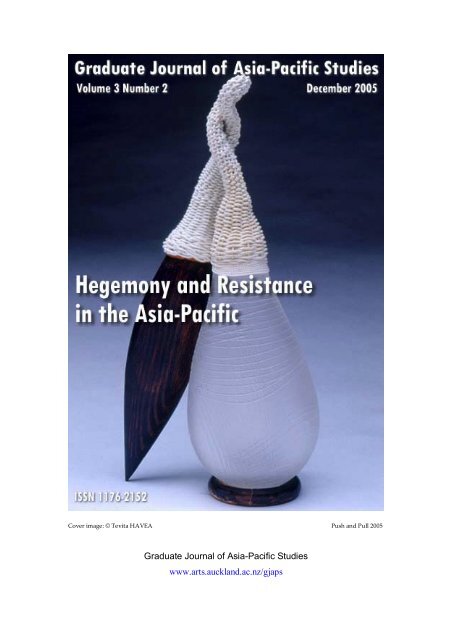

Cover image: © Tevita HAVEA Push <strong>and</strong> Pull 2005<br />

Graduate Journal of <strong>Asia</strong>-<strong>Pacific</strong> Studies<br />

www.arts.auckl<strong>and</strong>.ac.nz/gjaps

Graduate Journal of <strong>Asia</strong>-<strong>Pacific</strong> Studies<br />

<strong>Volume</strong> 3, <strong>Number</strong> 2, December 2005<br />

<strong>Hegemony</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Resistance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Asia</strong>-<strong>Pacific</strong><br />

Editorial<br />

<strong>Hegemony</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Resistance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Asia</strong>-<strong>Pacific</strong><br />

Visual essay<br />

Tevita Havea, Push <strong>and</strong> Pull<br />

Creative writ<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Tonglu Li, The F<strong>in</strong>al Confession of Mistress Wang<br />

Articles<br />

1. Elena Kolesova, Struggle from <strong>the</strong> Marg<strong>in</strong>s: Hokkaido<br />

Popular Education Movement <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Tower<strong>in</strong>g Shadow of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Japanese Exam<strong>in</strong>ation System (1950-1969)<br />

2. A<strong>the</strong>na Nguyen, I’m Not Racist, I Eat Dim Sims!: The<br />

Commodification <strong>and</strong> Consumption of <strong>Asia</strong>nness with<strong>in</strong><br />

White Australia<br />

3. Elena Atanassova-Cornelis, Japan <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘Human Security’<br />

Debate: History, Norms <strong>and</strong> Pro-active Foreign Policy<br />

Visual essay<br />

Brydee Rood, Habitat – with an <strong>in</strong>terview by W<strong>in</strong>some Wild<br />

Reviews<br />

1. Kathy Ooi, review of Sharon Carstens, Histories, Cultures,<br />

Identities: studies <strong>in</strong> Malaysian Ch<strong>in</strong>ese worlds<br />

2. Margaret Barnhill Bodemer, review of Christoph Giebel,<br />

Imag<strong>in</strong>ed Ancestries of Vietnamese Communism: Ton Duc Thang<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Politics of History <strong>and</strong> Memory<br />

3. Tim Neale, review of Haruki Murakami, Kafka on <strong>the</strong> shore<br />

4. Chris Payne review of Tom Mes, The Midnight Eye Guide to<br />

New Japanese Film <strong>and</strong> Donald Richie, The Japan Journals 1947-<br />

2004<br />

Article abstracts <strong>and</strong> biographical notes<br />

3-5<br />

6-12<br />

13-26<br />

27-44<br />

45-57<br />

58-74<br />

75-85<br />

86-89<br />

90-92<br />

93-96<br />

97-102<br />

103-106<br />

2<br />

www.arts.auckl<strong>and</strong>.ac.nz/gjaps

Graduate Journal of <strong>Asia</strong>-<strong>Pacific</strong> Studies<br />

3:2 (2005), 3-5<br />

EDITORIAL <strong>Volume</strong> 3, <strong>Number</strong> 2, December 2005<br />

<strong>Hegemony</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Resistance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Asia</strong>-<strong>Pacific</strong><br />

WELCOME TO <strong>Volume</strong> 3 <strong>Number</strong> 2 of <strong>the</strong> Graduate Journal of <strong>Asia</strong>-<strong>Pacific</strong> Studies. In<br />

this edition contributors have addressed <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>me of ‘<strong>Hegemony</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Resistance</strong> <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Asia</strong>-<strong>Pacific</strong>’.<br />

Individual <strong>and</strong> community experience <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Asia</strong>-<strong>Pacific</strong> region is characterised by<br />

deep disparities drawn along <strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>es of class, race, gender, sexuality, (dis)ability,<br />

nationality, <strong>and</strong> faith. These disparities are <strong>the</strong> material evidence of cont<strong>in</strong>ued<br />

dom<strong>in</strong>ation of certa<strong>in</strong> groups by o<strong>the</strong>rs through a comb<strong>in</strong>ation of political <strong>and</strong><br />

ideological means — or hegemony. While <strong>the</strong> scope of this conceptualisation of<br />

hegemony might differ from Gramsci’s orig<strong>in</strong>al, <strong>the</strong>re is no doubt that his assertion<br />

that <strong>the</strong> exercise of power pervades life from macro- to micro-experience still holds<br />

true. Indeed, if we are to glance quickly at our own nations’, cities, neighbourhoods<br />

or even homes — as some of <strong>the</strong> contributors to this edition do — <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> exercise of<br />

hegemonic power will become only too apparent. Concomitantly, power, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

Foucaultian sense, is never a zero-sum game. Instead, power is always cont<strong>in</strong>gent,<br />

always <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mak<strong>in</strong>g, never complete <strong>and</strong> always subject to contestation <strong>and</strong><br />

resistance. Moreover, because hegemonic power pervades all aspects of our lives,<br />

<strong>the</strong> opportunities to resist it or at least contest its mean<strong>in</strong>gs are also ever present. The<br />

contributions <strong>in</strong> this issue offer different approaches to underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g hegemony<br />

<strong>and</strong> resistance <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Asia</strong>-<strong>Pacific</strong> region. Rang<strong>in</strong>g from everyday experience to<br />

<strong>in</strong>stitutional politics <strong>and</strong> from consumption to security, <strong>the</strong>y each rem<strong>in</strong>d us of <strong>the</strong><br />

cont<strong>in</strong>ued centrality of questions of power to an underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Asia</strong>-<strong>Pacific</strong><br />

region <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>deed <strong>the</strong> world.<br />

The sculpture of Tevita Havea, a Tongan-born Australian artist, boldly adorns <strong>the</strong><br />

cover <strong>and</strong> revolv<strong>in</strong>g homepage. Draw<strong>in</strong>g on his experience of mov<strong>in</strong>g between<br />

Tongan <strong>and</strong> Australian society, Havea illustrates <strong>the</strong> deep tension that can exist<br />

between cultures <strong>and</strong> cultural systems. He addresses <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>me of ‘<strong>Hegemony</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Resistance</strong>’ by consider<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> ‘push <strong>and</strong> pull’ of different <strong>in</strong>fluences on his life <strong>and</strong><br />

rem<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g us of <strong>the</strong> difficulty <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> resist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> ‘collective weight’ of culture.<br />

Work<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>the</strong> ref<strong>in</strong>ement of glass <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> rawness of traditional materials<br />

Havea’s work is a testament to <strong>the</strong> possibility for <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>and</strong> groups to resist<br />

hegemony <strong>and</strong> create new hybrid subjectivities.<br />

Tonglu Li abruptly shifts our focus from this very contemporary experience of<br />

transnationality to <strong>the</strong> site (<strong>and</strong> sight) of a bloody L<strong>in</strong>gchi execution <strong>in</strong> Imperial Ch<strong>in</strong>a.<br />

His creative writ<strong>in</strong>g piece, ‘The F<strong>in</strong>al Confession of Mistress Wang’, challenges<br />

gendered roles <strong>in</strong> traditional literature by mak<strong>in</strong>g space for female experience <strong>in</strong><br />

Editorial: <strong>Hegemony</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Resistance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Asia</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> 3

what is typically a male narrative. The central character of his story, Mistress Wang,<br />

speaks, th<strong>in</strong>ks <strong>and</strong> dreams as her executioners slowly disembowel her. As she does<br />

so we learn of <strong>the</strong> complex <strong>in</strong>terpersonal webs that have brought Mistress Wang to<br />

her current situation <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> ways <strong>in</strong> which her actions have challenged <strong>and</strong><br />

underm<strong>in</strong>ed her gendered role <strong>in</strong> Imperial Ch<strong>in</strong>a. The story reveals issues of<br />

hegemony <strong>and</strong> resistance that are relevant across cultures <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>deed across different<br />

historical contexts.<br />

<strong>Resistance</strong> to normative power is also an important <strong>the</strong>me <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> first article by Elena<br />

Kolesova. Her article discusses local resistance to <strong>the</strong> development of <strong>the</strong> Japanese<br />

exam<strong>in</strong>ation system. Often framed with<strong>in</strong> discourses of economic nationalism, <strong>the</strong><br />

highly discipl<strong>in</strong>ed Japanese approach to academic achievement has been <strong>the</strong> subject<br />

of both praise <strong>and</strong> criticism from <strong>in</strong>ternational commentators. Kolesova, however,<br />

exam<strong>in</strong>es actions of a small popular education movement from Hokkaido, Japan’s<br />

nor<strong>the</strong>rn-most isl<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir attempts to challenge <strong>the</strong> national approach to<br />

education. Through her analysis, Kolesova illustrates how <strong>the</strong> representation of<br />

popular consensus around issues like education can often shroud discursive <strong>and</strong><br />

material resistance to state hegemony.<br />

Shift<strong>in</strong>g our attention from educational pedagogy to racialised consumption<br />

practices, A<strong>the</strong>na Nguyen discusses <strong>the</strong> hegemonic construction of ‘<strong>Asia</strong>nness’ <strong>in</strong><br />

contemporary white Australia. While leav<strong>in</strong>g room for resistant <strong>in</strong>terpretations,<br />

Nguyen purposefully makes visible <strong>the</strong> desire for difference <strong>and</strong> novelty that is at<br />

<strong>the</strong> centre of consum<strong>in</strong>g ‘<strong>Asia</strong>’ <strong>in</strong> everyday products. She argues that such<br />

consumption cannot be <strong>the</strong> basis for shared cultural <strong>in</strong>teraction but only cont<strong>in</strong>ued<br />

patterns of racial dom<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> exploitation <strong>in</strong> everyday life.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> third article of this edition, Elena Atanassova-Cornelis br<strong>in</strong>gs us back to <strong>the</strong><br />

discourses <strong>and</strong> practices of <strong>the</strong> Japanese state. In contrast to Kolesova’s article<br />

however, Atanassova-Cornelis identifies <strong>the</strong> ways that <strong>the</strong> development of Japanese<br />

foreign policy has served as part of <strong>the</strong> ongo<strong>in</strong>g contestation around <strong>the</strong> concept of<br />

‘human security’. Atanassova-Cornelis argues that <strong>the</strong> unique approach to<br />

<strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g human security <strong>in</strong> Japan reflects <strong>the</strong> ongo<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tersection of historical<br />

norms, policy preferences <strong>and</strong> pressure from <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational community.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> second visual essay, Brydee Rood challenges us to reconsider <strong>the</strong> environment<br />

we live <strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> way that we perceive <strong>the</strong> everyday objects that surround us. By<br />

modify<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> look <strong>and</strong> purpose of apparently ‘mean<strong>in</strong>gless’ objects, Rood reveals<br />

<strong>the</strong> way that our underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of such objects is <strong>the</strong> result of assumed uses <strong>and</strong><br />

constructed mean<strong>in</strong>gs. Rood’s arrangements are accompanied by an <strong>in</strong>trigu<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>terview with Art Editor W<strong>in</strong>some Wild that delves <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> broader context for<br />

Rood’s work <strong>and</strong> places it both <strong>in</strong>ternationally <strong>in</strong> Japan <strong>and</strong> Mexico <strong>and</strong> locally <strong>in</strong><br />

Auckl<strong>and</strong>, Aotearoa/New Zeal<strong>and</strong>.<br />

This edition also features reviews of five recent publications. Of note, Kathy Ooi<br />

discusses Histories, Cultures, Identities: studies <strong>in</strong> Malaysian Ch<strong>in</strong>ese worlds, a recent<br />

publication from S<strong>in</strong>gapore University Press that challenges <strong>the</strong> homogenous<br />

4<br />

www.arts.auckl<strong>and</strong>.ac.nz/gjaps

epresentation of overseas Ch<strong>in</strong>ese communities. Likewise, Margaret Barnhill<br />

Bodemer’s review of Imag<strong>in</strong>ed Ancestries of Vietnamese Communism: Ton Duc Thang <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Politics of History <strong>and</strong> Memory reveals <strong>the</strong> ongo<strong>in</strong>g power struggles that occur <strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> construction of national histories. Tim Neale <strong>and</strong> Chris Payne round off <strong>the</strong><br />

review section with excellent reviews of Haruki Murakami’s Kafka on <strong>the</strong> Shore<br />

(Neale), Tom Mes’s The Midnight Eye Guide to New Japanese Film (Payne) <strong>and</strong> Donald<br />

Richie’s The Japan Journals 1947-2004 (Payne).<br />

In o<strong>the</strong>r matters, a call for papers for <strong>Volume</strong> 4 <strong>Number</strong> 1 will be issued follow<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong> publication of this edition of GJAPS. The <strong>the</strong>me for that edition, ‘Navigat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

Future: <strong>Asia</strong>-<strong>Pacific</strong> pathways’ will encourage contributors to consider <strong>the</strong> multiple<br />

types of movement <strong>and</strong> mobility (or lack of it) that contribute to <strong>the</strong> current<br />

experience of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Asia</strong>-<strong>Pacific</strong> region.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, this edition marks ano<strong>the</strong>r development <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> relatively short history of<br />

GJAPS. It is <strong>the</strong> first edition published under a largely reorganised editorial<br />

committee. As such, I would like to take this opportunity to congratulate outgo<strong>in</strong>g<br />

editor Michael O’Shaughnessy <strong>and</strong> all <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r committee members who have<br />

departed – your contribution to <strong>the</strong> success of GJAPS has been <strong>in</strong>valuable. I would<br />

also like to thank all of <strong>the</strong> new <strong>and</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g committee members who have put so<br />

much effort <strong>in</strong>to mak<strong>in</strong>g this edition a reality.<br />

Francis Leo COLLINS<br />

University of Auckl<strong>and</strong><br />

Editorial: <strong>Hegemony</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Resistance</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Asia</strong> <strong>Pacific</strong> 5

Graduate Journal of <strong>Asia</strong>-<strong>Pacific</strong> Studies<br />

3:2 (2005), 6-12<br />

Push <strong>and</strong> Pull<br />

Tevita HAVEA<br />

Australian National University<br />

1. Push <strong>and</strong> Pull (2005) 8<br />

2. Mapa (2005) 9<br />

3. Voodoo Chime 1 (2005) 9<br />

4. Modern Primitive (2005) 10<br />

5. Voodoo Chime 2 (2005) 11<br />

6. Untitled (2005) 11<br />

7. Maea (2005) 12<br />

ARTIST’S STATEMENT<br />

I am part of an old culture full of myths, but I live <strong>in</strong> a modern<br />

world full of facts. There are so many contradictions...<br />

I AM forever bound to an ancient Tongan culture that deeply <strong>in</strong>fluences <strong>the</strong> way I<br />

th<strong>in</strong>k <strong>and</strong> feel. Like any community, <strong>the</strong>re are burdens that come with <strong>the</strong> privilege<br />

of belong<strong>in</strong>g. There are religious dem<strong>and</strong>s, strict family traditions <strong>and</strong> rituals that are<br />

both beautiful <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>timately stifl<strong>in</strong>g. Contemporary culture no longer respects<br />

ancient myths, view<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m as noth<strong>in</strong>g more than mere superstition. Rituals such as<br />

scarification, circumcision, tattoo<strong>in</strong>g or pierc<strong>in</strong>g may be viewed as extreme <strong>and</strong><br />

savage, as irrelevant to <strong>the</strong> complexities of modern life. Yet <strong>the</strong> ancient rituals <strong>and</strong><br />

traditions that all members of a community go through that physically alter <strong>the</strong> body,<br />

b<strong>in</strong>ds an <strong>in</strong>dividual emotionally <strong>and</strong> spiritually to a family, community <strong>and</strong> culture<br />

forever, through a physical <strong>and</strong> psychical transformation. Beneath <strong>the</strong> surface of<br />

primal ideology <strong>the</strong>re is wisdom <strong>and</strong> truth. Through <strong>the</strong>se rituals <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiations you<br />

are drawn to someth<strong>in</strong>g greater than yourself, you f<strong>in</strong>d pieces of who you are <strong>and</strong><br />

where you fit <strong>in</strong>.<br />

My work is fed by <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>-betweens of culture, <strong>the</strong> tension between oppos<strong>in</strong>g<br />

forces, <strong>the</strong> privilege <strong>and</strong> burden of belong<strong>in</strong>g to a Tongan community <strong>and</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a<br />

western country. It is <strong>the</strong> tension between <strong>the</strong> rawness of <strong>the</strong> ‘primitive’, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

‘ref<strong>in</strong>ement’ of contemporary culture that I voice with<strong>in</strong> my work. It is <strong>the</strong> "push <strong>and</strong><br />

pull" of different <strong>in</strong>fluences that I attempt to reconcile <strong>and</strong> to balance. The pull of<br />

culture is seductive; <strong>the</strong> gravity of its hypnotic push is re<strong>in</strong>forced by <strong>the</strong> recruitment<br />

of each new member, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> collective momentum is fueled by <strong>the</strong> convictions of<br />

each person. It is challeng<strong>in</strong>g to struggle aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> collective weight <strong>and</strong> break <strong>the</strong><br />

unbreakable. The majority of my life has been spent <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Western world <strong>and</strong> it has<br />

6<br />

www.arts.auckl<strong>and</strong>.ac.nz/gjaps

opened my eyes to new possibilities. These contradict many of my early traditional<br />

perceptions <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> attempt to break away from some of my romantic Polynesian<br />

notions, I f<strong>in</strong>d myself <strong>in</strong>-between worlds. There are always contradictions when <strong>the</strong>re<br />

are two oppos<strong>in</strong>g forces, but <strong>in</strong>stead of one dom<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r, I aim to create<br />

pieces that are nei<strong>the</strong>r ancient nor contemporary, but operate to explore <strong>the</strong> tensions<br />

of <strong>the</strong> space between. Rituals may vary from culture to culture but <strong>the</strong> effect is <strong>the</strong><br />

same, we are seduced by our culture <strong>and</strong> are drawn to someth<strong>in</strong>g greater that is<br />

universal.<br />

Ofa atu<br />

Tevita Havea is a contemporary artist who was born <strong>in</strong> Tonga <strong>and</strong> moved to Sydney<br />

at <strong>the</strong> age of ten. Tevita studies Visual Art at <strong>the</strong> Australian National University<br />

School of Art, major<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> glass <strong>and</strong> sub-major<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> sculpture.<br />

Havea/Push <strong>and</strong> Pull 7

© Tevita HAVEA Push <strong>and</strong> Pull (2005)<br />

8<br />

www.arts.auckl<strong>and</strong>.ac.nz/gjaps

© Tevita HAVEA Mapa (2005)<br />

© Tevita HAVEA Voodoo Chime 1 (2005)<br />

Havea/Push <strong>and</strong> Pull 9

© Tevita HAVEA Modern Primitive (2005)<br />

10<br />

www.arts.auckl<strong>and</strong>.ac.nz/gjaps

© Tevita HAVEA Voodoo Chime 2 (2005)<br />

© Tevita HAVEA Untitled (2005)<br />

Havea/Push <strong>and</strong> Pull 11

© Tevita HAVEA Maea (2005)<br />

12<br />

www.arts.auckl<strong>and</strong>.ac.nz/gjaps

The F<strong>in</strong>al Confession of Mistress Wang<br />

Tonglu LI<br />

University of Ill<strong>in</strong>ois at Urbana-Champaign<br />

Graduate Journal of <strong>Asia</strong>-<strong>Pacific</strong> Studies<br />

3:2 (2005), 13-26<br />

Introduction<br />

THIS IS a short story about Mistress Wang, a figure that appeared <strong>in</strong> both Water<br />

Marg<strong>in</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Plum <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Golden Vase. You might already know why <strong>and</strong> how she<br />

was killed by read<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> two novels, or by watch<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> TV serial based on <strong>the</strong> first<br />

novel. Pla<strong>in</strong>ly speak<strong>in</strong>g, she brought Ximen Q<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>the</strong> rich, corrupted merchant, <strong>and</strong><br />

Pan J<strong>in</strong>lian — <strong>the</strong> Golden Lotus — toge<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>and</strong> provided room for <strong>the</strong>ir adultery.<br />

Of course, she did not do this for free. Ximen Q<strong>in</strong>g paid her h<strong>and</strong>somely. However,<br />

<strong>the</strong> story did not develop <strong>in</strong>to a romantic one. Wang encouraged Pan to murder her<br />

husb<strong>and</strong> Wu Da (Wu <strong>the</strong> Elder), after Wu confronted Pan about her affair with<br />

Ximen Q<strong>in</strong>g. Mistress Wang was highly <strong>in</strong>volved, <strong>and</strong> so also met her dest<strong>in</strong>y. In <strong>the</strong><br />

b<strong>and</strong>it-centred fiction Water Marg<strong>in</strong>s, Pan <strong>and</strong> Ximen were killed by Wu Song, out of<br />

revenge for <strong>the</strong> murder of his elder bro<strong>the</strong>r. Mistress Wang was executed with<br />

L<strong>in</strong>gchi 1 by <strong>the</strong> government <strong>in</strong> Dongp<strong>in</strong>g Fu (Prefecture of Dongp<strong>in</strong>g, 东 平 府 ), <strong>the</strong><br />

higher authority of her hometown Q<strong>in</strong>ghe Xian (Clear Water County, 清 河 县 ). Wu<br />

Song witnessed <strong>the</strong> process before his own exile. In The Plum <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Golden Vase, <strong>the</strong><br />

author borrows <strong>the</strong> bloody plot from Water Marg<strong>in</strong>s <strong>and</strong> makes it <strong>the</strong> start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t<br />

for <strong>the</strong> Pan J<strong>in</strong>lian-Ximen Q<strong>in</strong>g centred erotic story. He also made some<br />

modifications to facilitate his narrative <strong>in</strong>tentions. As a result, Mistress Wang was<br />

killed by Wu Song after he returned home years later from his exile. In my writ<strong>in</strong>g, I<br />

followed <strong>the</strong> first end<strong>in</strong>g but moved <strong>the</strong> execution scene back to Clear Water <strong>in</strong> order<br />

to make it more spectacular.<br />

Mistress Wang was <strong>in</strong>dispensable <strong>in</strong> mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> affair between Ximen Q<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>and</strong> Pan J<strong>in</strong>lian happen <strong>in</strong> both novels. However, she rema<strong>in</strong>ed a marg<strong>in</strong>al figure<br />

<strong>and</strong> did not get much attention from ei<strong>the</strong>r author. My <strong>in</strong>itial <strong>in</strong>tention was to<br />

explore Wang’s motivations assist<strong>in</strong>g Pan J<strong>in</strong>lian <strong>and</strong> Ximen Q<strong>in</strong>g. Besides her<br />

marvelous techniques of deploy<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> affair, what is <strong>in</strong> her m<strong>in</strong>d Is it someth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

more than money Is it revenge on men Is it for voyeuristic pleasure Or is it a<br />

desire to feel powerful by manipulat<strong>in</strong>g people of higher social status To explore<br />

<strong>the</strong>se I need to reconstruct her life story, her bubble-like dreams <strong>and</strong> her struggles to<br />

squeeze <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> society. Only by do<strong>in</strong>g this can we fabricate a “logic” for her life<br />

story <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> world she lived <strong>in</strong> from her perspective.<br />

This, of course, is not an endeavor to restore <strong>the</strong> real historical moment, if <strong>the</strong>re<br />

is one. It <strong>in</strong>tends to re-imag<strong>in</strong>e a woman, whose life deserves to be <strong>the</strong> subject of<br />

many books, based on <strong>the</strong> relatively pla<strong>in</strong> accounts <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> two novels mentioned<br />

above. However, textualization of her life is as difficult as try<strong>in</strong>g to build a solid<br />

statue referr<strong>in</strong>g to a pale shadow. Therefore, <strong>in</strong> this short piece <strong>the</strong> presentation of<br />

her m<strong>in</strong>d is more than <strong>the</strong> elaboration of everyday life. Stylistically, it might be said<br />

that <strong>the</strong>re is some similarity with Lu Xun’ s Old Tales Retold <strong>in</strong> that I <strong>in</strong>clude some<br />

Li/The F<strong>in</strong>al Confession of Mistress Wang 13

eferences to contemporary terms, events <strong>and</strong> discussions, which <strong>in</strong>terrupt <strong>the</strong> flow<br />

of narration. They might do this, but <strong>the</strong>y also exp<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> textural space. Mostly,<br />

however, it is for fun, because <strong>the</strong> execution scene is too serious. F<strong>in</strong>ally, I followed<br />

my pen <strong>and</strong> I produced a Mistress Wang – a victimized victimizer, a contam<strong>in</strong>ated<br />

contam<strong>in</strong>ator, who should have cried but had to smile <strong>and</strong> who could be any woman<br />

at her time <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> her situation.<br />

The story is framed with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> site of her execution. I could not help putt<strong>in</strong>g<br />

certa<strong>in</strong> weight on <strong>the</strong> reactions of <strong>the</strong> onlookers of <strong>the</strong> execution, <strong>the</strong>ir excitement,<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir desire to see <strong>the</strong> bloody scene. This concern is really <strong>in</strong>spired by modern<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>ese writers, especially Lu Xun. However, I had no <strong>in</strong>tention of cast<strong>in</strong>g<br />

aspersions on <strong>the</strong>se people from a so-called “elite” perspective, not only because I<br />

could be one of <strong>the</strong>m, but also because everyone could be one of <strong>the</strong>m. I was just<br />

curious about how <strong>the</strong> pedagogical-<strong>in</strong>tent of <strong>the</strong> violent scene that <strong>the</strong> government<br />

used to threaten its citizens was transformed <strong>in</strong>to a spectacle or a carnival. I also<br />

doubted whe<strong>the</strong>r this phenomenon had ext<strong>in</strong>guished today, ra<strong>the</strong>r than be<strong>in</strong>g<br />

transformed <strong>in</strong>to o<strong>the</strong>r scenes. Now let us go <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> story.<br />

梦 过 清 河 2<br />

迷 蒙 紫 蝶 翩 翩 舞<br />

王 婆<br />

3<br />

茶 肆 依 然 在<br />

过 遍 长 街 无 人 识<br />

醒 来 还 忆 当 日 路<br />

古 城 烟 雨 一 梦 游<br />

西 门<br />

4<br />

衰 草 卧 墙 头<br />

闲 看 清 河 水 东 流<br />

几 时 明 月 照 西 楼<br />

The Street, <strong>the</strong> Butterfly 5<br />

For some people, <strong>the</strong> crowded dust-swirl<strong>in</strong>g streets are a stage. To enjoy it, you can<br />

ei<strong>the</strong>r be an actor, or a spectator. For some people, <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>al scene of <strong>the</strong>ir life is<br />

performed on this stage. They know that <strong>the</strong>ir dest<strong>in</strong>y will not be different from that<br />

of o<strong>the</strong>rs whom <strong>the</strong>y watch on this stage for fun.<br />

This of course was five hundred years ago. Today <strong>the</strong> streets are taken over by<br />

cars <strong>and</strong>, s<strong>in</strong>ce we have evolved to become more modern <strong>and</strong> civilized, some scenes<br />

are not appropriate for public anymore, especially as enterta<strong>in</strong>ment. For example, we<br />

can still kill crim<strong>in</strong>als or enemies, but for <strong>the</strong> risk of contam<strong>in</strong>ation, especially of our<br />

children, or to show our benevolence to <strong>the</strong>se dead people, we do not allow<br />

ourselves to see it. And nobody shares <strong>the</strong> excitement with Ah Q, who once said,<br />

“Have you seen a decapitation Amaz<strong>in</strong>g! Amaz<strong>in</strong>g!” 6 As substitutes, people turn to<br />

TV or film to have fun. Five hundred years ago, when <strong>the</strong>re was no TV or film,<br />

people could still get <strong>the</strong> same pleasure by o<strong>the</strong>r means, just by go<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> streets,<br />

even <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> prov<strong>in</strong>cial town Clear Water County <strong>in</strong> Sh<strong>and</strong>ong, Central K<strong>in</strong>gdom. As<br />

you can guess now, a fantastic scene, which has been <strong>and</strong> would be repeated for<br />

many years <strong>and</strong> on many streets has f<strong>in</strong>ally become a favourite enjoyment, a<br />

spectacle mak<strong>in</strong>g many eyes pleased <strong>and</strong> excited: L<strong>in</strong>gchi-<strong>in</strong>g a crim<strong>in</strong>al.<br />

It is an ord<strong>in</strong>ary sunny day on <strong>the</strong> Ma<strong>in</strong> Street of Clear Water Country. When<br />

birds start chirp<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> peddlers start to br<strong>in</strong>g out <strong>the</strong>ir commodities, <strong>the</strong><br />

residents are just gett<strong>in</strong>g out of <strong>the</strong>ir dreams when bow<strong>in</strong>g to each o<strong>the</strong>r with smiles<br />

<strong>and</strong> greet<strong>in</strong>gs. Mistress Wang, who has already become part of a legend, a bloody<br />

revenge, after months of imprisonment, sees <strong>the</strong> sunsh<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> familiar streets for<br />

14<br />

www.arts.auckl<strong>and</strong>.ac.nz/gjaps

<strong>the</strong> first time. It is for <strong>the</strong> first time <strong>in</strong> her life she realizes how beautiful <strong>and</strong> splendid<br />

a thread of sunsh<strong>in</strong>e is when it comes through <strong>the</strong> grey branches <strong>and</strong> twigs, <strong>and</strong> how<br />

lovely <strong>the</strong> street is when so many people <strong>and</strong> cabs flow over it with <strong>the</strong>ir many<br />

sounds <strong>and</strong> voices. But it is all too late for her. Soon she will become a spectacle to be<br />

enjoyed by her former neighbors <strong>and</strong> unfamiliar people. “You will be cut to<br />

thous<strong>and</strong> pieces” has been her favorite curse to those who tried to pay less or not pay<br />

<strong>in</strong> her teahouse. Soon she will know how it tastes. She has been <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> audience of<br />

executions for a long time. There have been performances of behead<strong>in</strong>g, cutt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><br />

two at <strong>the</strong> waist, tear<strong>in</strong>g a body limb from limb by five horses, <strong>and</strong> so on. But even<br />

<strong>the</strong> most delicate L<strong>in</strong>gchi could not attract her any more after so many. The scene is<br />

not a book <strong>in</strong> which you can always f<strong>in</strong>d new mean<strong>in</strong>g. Today she becomes <strong>the</strong><br />

actress on <strong>the</strong> stage. There are many spectators <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> performance will be long.<br />

Why so long They say <strong>the</strong> longer you suffer <strong>the</strong> better for <strong>the</strong> people to release <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

hatred. When she sees <strong>the</strong> smiles on familiar faces, a chill passes over her body.<br />

“My bro<strong>the</strong>rs, could you make it quick Still remember <strong>the</strong> free tea”<br />

“Don’t call us that, Mistress Wang. You are a smart person. You are too smart.<br />

If you only sell tea, who dares to put you here Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, this is our job. You are<br />

dead anyway. If we give you a quick death, people would not allow us <strong>and</strong> we will<br />

be fired. It is so hard <strong>the</strong>se days to f<strong>in</strong>d a job.”<br />

“I see. Would you do me a favor tell<strong>in</strong>g my son Wang Chao ( 王 潮 ) 7 to bury me<br />

He is <strong>in</strong> Yuncheng city do<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess now.”<br />

“Don’t you worry about anyth<strong>in</strong>g, Mistress Wang! Once we send you on your<br />

way, everyth<strong>in</strong>g will be f<strong>in</strong>e.”<br />

The sun is ris<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> people are ga<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>g. They are wait<strong>in</strong>g for THAT moment.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, she is tied on <strong>the</strong> frame called wood donkey. Her mouth is also tied up to<br />

prevent her from curs<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> sacred. The executors are very good at <strong>the</strong>ir job. She is<br />

processed so quickly <strong>and</strong> neatly that it looks like <strong>the</strong>y are show<strong>in</strong>g off. Her clo<strong>the</strong>s,<br />

bought with <strong>the</strong> silver Ximen Q<strong>in</strong>g paid her, now worn <strong>and</strong> ragged, are torn off.<br />

People start to scream <strong>and</strong> comment on her body; maybe <strong>the</strong>y wonder how such a<br />

weak <strong>and</strong> pale body can conta<strong>in</strong> such an energetic “evil” soul, which brought several<br />

people <strong>in</strong>to death.<br />

“Oh! Look! Still white <strong>and</strong> tender…”<br />

“What a pity! I cannot… I should have…”<br />

“Hahaha… What are you th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g about She could be your mo<strong>the</strong>r!”<br />

“Hi! Young men, watch your mouths! And learn someth<strong>in</strong>g ethical…”<br />

“You want me to learn someth<strong>in</strong>g moral How about you <strong>and</strong> your<br />

daughter-<strong>in</strong>-law… isn’t she good” 8<br />

“She deserves it! The evil bitch! I have known from <strong>the</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g that she is<br />

evil…I never let my family go to her teahouse. She is a “professor” to teach men to<br />

steal <strong>and</strong> women to sell <strong>the</strong>mselves. Unless I have to borrow someth<strong>in</strong>g…”<br />

“Amida Buddha 9 ! It is a s<strong>in</strong>, a s<strong>in</strong>. People only follow <strong>the</strong>ir desires…revenge<br />

followed by revenge, where is <strong>the</strong> end Go home! Go home! Witness<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><br />

destroy<strong>in</strong>g of evil doesn’t make you sa<strong>in</strong>t. Ai! The sky is fall<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> nobody listens to<br />

me…”<br />

More <strong>and</strong> more people are ga<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

People. She has been one of <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>and</strong> spit on o<strong>the</strong>r crim<strong>in</strong>als. She knows<br />

almost all of <strong>the</strong>m. They go to her teahouse, ask for o<strong>the</strong>rs’ secrets, or ask her to get<br />

Li/The F<strong>in</strong>al Confession of Mistress Wang 15

<strong>the</strong>m a wife… But today <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir eyes she becomes an alien, someth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>y can<br />

enjoy. And how familiar <strong>the</strong>se conversations are! Noth<strong>in</strong>g is new under <strong>the</strong> sun.<br />

The execution f<strong>in</strong>ally starts. Piece by piece, every cut is accurate <strong>and</strong> stimulates<br />

a scream—not from her, but from <strong>the</strong> onlookers. Is it pa<strong>in</strong>ful She can feel it but she<br />

cannot say it out loud. Pa<strong>in</strong> cannot accumulate endlessly. To a po<strong>in</strong>t it will make you<br />

numb, just as when you dr<strong>in</strong>k too much. Yes, dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g. It seems even you can watch<br />

it calmly. People become cloudy; <strong>the</strong>ir voices become fussy, like <strong>the</strong> flow of spr<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

river. Nobody knows s<strong>in</strong>ce when, a butterfly always flies up <strong>and</strong> down <strong>in</strong> front of<br />

her eyes. For a moment she will th<strong>in</strong>k,<br />

“Am I dream<strong>in</strong>g Where are you from Why are you here Are you com<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

take me away Do you want to know my life story, my butterfly I cannot speak, but<br />

you can hear me. Am I right”<br />

The colourful butterfly, with <strong>the</strong> silent <strong>and</strong> slow flutter<strong>in</strong>g of its w<strong>in</strong>gs, calms<br />

her down, <strong>and</strong> leads her to her past for <strong>the</strong> first time, <strong>and</strong> for <strong>the</strong> last time. She was<br />

too busy before, but what for And now she would not be busy ever aga<strong>in</strong>. There is<br />

no more need for calculations, fabrications, <strong>and</strong> no need for hard work. Isn’t it good<br />

… What year was it And what season was it when all that happened What place<br />

What really happened Th<strong>in</strong>gs pass like float<strong>in</strong>g cloud <strong>and</strong> smoke. But <strong>the</strong>ir shadows<br />

would be impressed <strong>in</strong> your dreams. …<br />

The Dreams<br />

“My dreams are very short, as short as this street is.”<br />

“Mistress Wang, <strong>the</strong>y call me now. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong>y started call<strong>in</strong>g me a “girl”, I realized<br />

how poor we were. I dreamed of hav<strong>in</strong>g mirror, but could not afford one. But<br />

through <strong>the</strong>ir eyes I saw myself. ‘She is so ord<strong>in</strong>ary-look<strong>in</strong>g that she even cannot<br />

become a courtesan as her sisters two do.’ This was what I heard. But what is good to<br />

be a courtesan, my butterfly Every thread of <strong>the</strong>ir smiles <strong>in</strong> front of <strong>the</strong>ir clients,<br />

every smile is accompanied by drops of tears <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own small room. My sisters<br />

told me. I know my parents expected a son, but <strong>the</strong>y always got useless girls. They<br />

compla<strong>in</strong>ed to each o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>and</strong> I became <strong>the</strong> scapegoat, <strong>the</strong> vent for <strong>the</strong>ir anger <strong>and</strong><br />

despair. They hated me <strong>and</strong> ignored me, even when I tried to help <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> kitchen—I<br />

am embarrassed to say, that was not a kitchen.”<br />

“My butterfly, you might not believe it. I even did not get a formal first name.<br />

There are so many flowers <strong>and</strong> plants, but <strong>the</strong>y did not bo<strong>the</strong>r to pick one as my<br />

name. Orchard, chrysan<strong>the</strong>mums, lotus—no, forget about lotus. Before I was married,<br />

I was Wang <strong>the</strong> third girl. After that I was attached to my husb<strong>and</strong> Wang Zhu, <strong>the</strong>y<br />

called me “<strong>the</strong>-one-<strong>in</strong>-Wang Zhu’s-house”. And s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>the</strong> bastard died drunk <strong>and</strong><br />

young, I am simply Mistress Wang. But does a name really matter Did I lose<br />

anyth<strong>in</strong>g … Yes, sometimes I did not know who I was.”<br />

“I dreamed about fly<strong>in</strong>g away to a place where no one knows me <strong>and</strong> I live<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r with only cute animals like hares, deer <strong>and</strong> goats. No tigers, no wolves <strong>and</strong><br />

no foxes. Oh, those foxes. They always come <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> human world <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> guise of<br />

attractive women. They are beautiful. But s<strong>in</strong>ce when did <strong>the</strong>y start to enchant those<br />

shameless men My dreams were broken when I opened my eyes <strong>and</strong> saw my<br />

parents’ faces. They came aga<strong>in</strong> later like <strong>the</strong> little pitiful mice.”<br />

“Nobody played anyth<strong>in</strong>g with me because I did not even have an item of<br />

cloth<strong>in</strong>g without holes <strong>and</strong> patches on it. Sometimes I stood by <strong>the</strong> door watch<strong>in</strong>g<br />

16<br />

www.arts.auckl<strong>and</strong>.ac.nz/gjaps

little girls play<strong>in</strong>g. But my mo<strong>the</strong>r would curse me, ‘you little cheap th<strong>in</strong>g, do you<br />

want to sell yourself Nobody wants to pay for you! Go back to wash <strong>and</strong> clean!’ You<br />

see, my dreams were always <strong>in</strong>complete, as fragmented as <strong>the</strong> footpr<strong>in</strong>ts on today’s<br />

street.”<br />

“Technically—this term might be embarrass<strong>in</strong>g, but I like it, I like anyth<strong>in</strong>g that<br />

can be h<strong>and</strong>led, can be divided. Technically, I did not have a dream about my life at<br />

all. I was married to a man before I started dream<strong>in</strong>g about a man. I did not get<br />

anyth<strong>in</strong>g from my parents—<strong>the</strong>y did not have anyth<strong>in</strong>g. Only my two sisters gave<br />

me a set of new clo<strong>the</strong>s <strong>and</strong> a mirror—I used it once <strong>and</strong> I did not like my face. Now<br />

it might be rusted <strong>and</strong> dusted. And I did not cry when I left my home. I had noth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to cry for—nei<strong>the</strong>r did my parents. And I did not know what my husb<strong>and</strong> paid <strong>the</strong>m<br />

for gett<strong>in</strong>g me. I did not care about it.”<br />

“My marriage was not so bad because my husb<strong>and</strong> did not beat me. A woman<br />

like me was just not his type. I am not attractive to him, maybe to any men. He<br />

<strong>in</strong>herited some property <strong>and</strong> started to gamble <strong>and</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k with o<strong>the</strong>r guys. They went<br />

to bro<strong>the</strong>ls toge<strong>the</strong>r. Sometimes he even brought those bitches home. Nobody could<br />

stop him. He was totally drowned <strong>in</strong> his desires. I could not stop him s<strong>in</strong>ce noth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> house belonged to me. I pleaded to some seniors of his clan to stop him. They<br />

were angry that his fa<strong>the</strong>r did not give <strong>the</strong>m anyth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y did not say a word. I<br />

was desperate. What could a woman do”<br />

“I did not care about him any more after we had our son. ‘I will rely on you,<br />

my son.’ I said this to my son, who was still not able to speak a word. Maybe I<br />

should tell you, my butterfly. It was me who gave my son a name, Wang Chao 10 . I<br />

hoped that he always remembered to come back to me. As trustworthy as <strong>the</strong> tide, no<br />

matter how far away he goes. Now of course he is not here, <strong>and</strong> I am grateful for it.<br />

Oh my son, how could he face this, how could he endure <strong>the</strong> rumors beh<strong>in</strong>d his back<br />

if he was here, <strong>and</strong> could he have face to cont<strong>in</strong>ue liv<strong>in</strong>g here Maybe he will go to<br />

<strong>the</strong> water marg<strong>in</strong>s, but please don’t! Always remember, my son, even if you are as<br />

hard as steel, <strong>the</strong> government is <strong>the</strong> stove. Never try to confront <strong>the</strong> rule. If you want<br />

subvert it, abide by it first <strong>and</strong> remake for your own purposes.”<br />

“Also, I had to start calculat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> daily expenses. I had to plan for <strong>the</strong> future<br />

of my son. Where would <strong>the</strong> money come from Sometimes <strong>the</strong> dead bastard<br />

brought back some money <strong>and</strong> I had to skillfully steal little pieces. For several years I<br />

saved several taels of silver. One day my husb<strong>and</strong> was found dead <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> street.<br />

Some people said that his friends murdered him because he won lots of money that<br />

night. I cried for help from <strong>the</strong> mayor, but no one came to talk about it. They just<br />

followed <strong>the</strong> procedures <strong>and</strong> filled out some forms, as if it was an X-files case. 11 Later<br />

on I found out why. The mayor received lots of money from some people. For a<br />

moment maybe I should let my son go to <strong>the</strong> water marg<strong>in</strong>s. My butterfly, I do not<br />

want to tell you about my feel<strong>in</strong>gs of powerlessness <strong>and</strong> humiliation. The dead ghost<br />

never came <strong>in</strong>to my dream to give me a h<strong>in</strong>t, or to tell me if he hid some money<br />

somewhere I did not know about, for our son. But he never came to visit me. He<br />

def<strong>in</strong>itely had already forgotten us <strong>and</strong> started to play with o<strong>the</strong>r female ghosts <strong>in</strong><br />

hell.”<br />

Li/The F<strong>in</strong>al Confession of Mistress Wang 17

The Becom<strong>in</strong>g of Mistress Wang<br />

“From <strong>the</strong>n on I forgot about my dreams. I had to f<strong>in</strong>d a way out to raise my son.<br />

Anyth<strong>in</strong>g unpractical would be m<strong>in</strong>imized, unless my son liked it. I had to make<br />

detailed plans, to budget every penny, <strong>and</strong> to do risk analysis for manag<strong>in</strong>g our daily<br />

life.”<br />

“The untimely death of my husb<strong>and</strong> was my rebirth. Before he died, you know,<br />

even though he did noth<strong>in</strong>g, as long as he was <strong>the</strong>re, my heart was at peace. And no<br />

rumors went after me, <strong>and</strong> no need to contact with so many people. My butterfly,<br />

you might th<strong>in</strong>k I am play<strong>in</strong>g philosophical games to talk about Laozi’s ‘<strong>the</strong><br />

usefulness of uselessness’; 12 I am not. I am tell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> truth because after that my<br />

heart became empty <strong>and</strong> I had to fill it with someth<strong>in</strong>g. The outside pressures<br />

seemed to emerge from nowhere when <strong>the</strong>re was not a man <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> household. I had<br />

to play <strong>the</strong> role of a fa<strong>the</strong>r as well as a mo<strong>the</strong>r. I wanted to cry. But s<strong>in</strong>ce cry<strong>in</strong>g could<br />

not br<strong>in</strong>g any help, so I held back my tears.”<br />

“My parents would not allow me to go back to <strong>the</strong>ir home s<strong>in</strong>ce I would be a<br />

burden, <strong>and</strong> a widow always brought <strong>in</strong>convenience for <strong>the</strong>m. To tell you <strong>the</strong> truth, I<br />

would ra<strong>the</strong>r beg to raise my son than step <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>ir house aga<strong>in</strong>. But <strong>the</strong>y showed<br />

<strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> my son. Yes, my son, whom nobody can take away from me.”<br />

“S<strong>in</strong>ce my husb<strong>and</strong>’s death, many bachelors came to help me. But I could see<br />

from <strong>the</strong>ir slant eyes what <strong>the</strong>y wanted. I refused all <strong>the</strong>ir offers first. No man is<br />

reliable. But men can be manipulated. They look strong, but are driven by <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

desires. Later on, I thought why not use <strong>the</strong>m I kept my distance with <strong>the</strong>m,<br />

stimulated some jealousy <strong>and</strong> let <strong>the</strong>m compete with one ano<strong>the</strong>r, always lett<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir imag<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> hopes live. I did not care about <strong>the</strong> rumors. My son was still<br />

young <strong>and</strong> he understood noth<strong>in</strong>g.”<br />

“Although I could have had my choice for remarriage, I did not remarry for <strong>the</strong><br />

sake of my son. A woman is always a mo<strong>the</strong>r first. I did not want my son to be<br />

despised, to be bullied. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, where would I f<strong>in</strong>d a reliable man <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

county You want me to f<strong>in</strong>d a boor <strong>and</strong> move to <strong>the</strong> countryside No way. Those<br />

boors are as dumb as wood trunks. When <strong>the</strong>y come to <strong>the</strong> city, you can see from<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir astonished face how dumb <strong>the</strong>y are! Can you imag<strong>in</strong>e feed<strong>in</strong>g pigs <strong>and</strong> chicken<br />

everyday I had to f<strong>in</strong>d a better way out. Of course, this was my real th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g at that<br />

time. Now I do not like urban life anymore. It is too crowded <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>re is not a s<strong>in</strong>gle<br />

day that you can avoid <strong>the</strong> gaze of o<strong>the</strong>r people. There are too many desires <strong>and</strong> you<br />

will easily be drowned <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sea of lust <strong>and</strong> appetites.”<br />

“I had nowhere to go, so I stayed home. Luckily my relatives did not come to<br />

get <strong>the</strong> house s<strong>in</strong>ce I had a son. I thought it over, <strong>and</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ally I turned my house <strong>in</strong>to a<br />

teahouse. I spent most of my sav<strong>in</strong>gs on renovat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> decorat<strong>in</strong>g. However,<br />

open<strong>in</strong>g a teahouse is not as simple as mak<strong>in</strong>g tea <strong>and</strong> sell<strong>in</strong>g it. The bachelors still<br />

came to help, but <strong>the</strong>y were not powerful—if <strong>the</strong>y were, <strong>the</strong>y had already got women.<br />

There were gangsters, permits from government, tax, fees, <strong>and</strong> so on. At <strong>the</strong><br />

beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> gangsters came with dead flies <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir h<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y put <strong>the</strong>m <strong>in</strong>to<br />

<strong>the</strong> teapots. They said that I served <strong>the</strong>m dirty tea <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y broke everyth<strong>in</strong>g. They<br />

threatened to send me to see <strong>the</strong> mayor unless I paid <strong>the</strong>m a protection fee. I did<br />

some calculations, <strong>and</strong> realized that, to consider all of <strong>the</strong>se costs, I would be<br />

bankrupt <strong>in</strong> no time.”<br />

18<br />

www.arts.auckl<strong>and</strong>.ac.nz/gjaps

“To cont<strong>in</strong>ue my teahouse bus<strong>in</strong>ess I had to sleep with <strong>the</strong> gangsters, low<br />

officials, <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>in</strong> power. Sex seemed <strong>the</strong> last capital for me to <strong>in</strong>vest <strong>and</strong> I had<br />

to <strong>in</strong>vest wisely. Yes, I was not pretty, but I was young. For <strong>the</strong>m I was a free lunch. I<br />

satisfied <strong>the</strong>m, whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y were old or young, h<strong>and</strong>some or ugly, as long as <strong>the</strong>y<br />

helped me with my bus<strong>in</strong>ess, but I came to hate men more <strong>and</strong> more. When I slept<br />

with those men, I sent my son to <strong>the</strong> bank of Clear Water River. I sometimes could<br />

not hold my tears when he told me, ‘mom, I do not want to look at <strong>the</strong> water<br />

anymore’. Sometimes at night when I could not sleep, I persuaded myself, if I could<br />

not change <strong>the</strong> way of <strong>the</strong> world, I change my will, my way of see<strong>in</strong>g th<strong>in</strong>gs. Why<br />

not enjoy <strong>the</strong> men who came to me Why not take licentiousness as a compliment<br />

But when see<strong>in</strong>g my son <strong>the</strong>re, I would blame myself for what I did <strong>and</strong> what was <strong>in</strong><br />

my m<strong>in</strong>d. Yes, his mo<strong>the</strong>r could not be a lady of pleasure. I must hate each of <strong>the</strong>m!<br />

Gradually, I started fights among <strong>the</strong>se men. I let <strong>the</strong>m go aga<strong>in</strong>st each o<strong>the</strong>r for my<br />

revenge, for <strong>the</strong> humiliation I got, <strong>and</strong> to bury <strong>the</strong> shame. But I would leave <strong>the</strong> most<br />

powerful as reserve <strong>and</strong> back up. The world is a game <strong>and</strong> you have to know how to<br />

play. You damn stupid men! You th<strong>in</strong>k you were play<strong>in</strong>g me You were all played<br />

by me.”<br />

“I imag<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>and</strong> calculated at night when I woke up from nightmares—I did<br />

not have dreams anymore, I only had nightmares, <strong>in</strong> which I tried climb<strong>in</strong>g up a cliff<br />

but I always fell down to <strong>the</strong> abyss. I hated <strong>the</strong> chaotic daytime, but I was afraid of<br />

<strong>the</strong> quiet nights. My only hope was my son. I saved more <strong>and</strong> more silver <strong>and</strong> my<br />

son was grow<strong>in</strong>g up well. But I did not send him to school. Why not If he succeeded,<br />

he would leave me <strong>and</strong> became one of <strong>the</strong> corrupted officials. If he failed he would<br />

become useless, except for becom<strong>in</strong>g a poor teacher or serv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> illiterate rich or<br />

perverted powerful by his sour literary hackwork—to me that was an even lower<br />

status than <strong>the</strong> street women. Therefore I sent him to be an apprentice <strong>in</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess. I<br />

was glad that he enjoyed it. He did not <strong>in</strong>herit any bad habits from his fa<strong>the</strong>r. I<br />

would have beaten him to death if he did.”<br />

“I was becom<strong>in</strong>g old. For a woman forty is too old. I do not know or care how<br />

<strong>the</strong> poor <strong>and</strong> sour literati elaborate <strong>and</strong> sigh for <strong>the</strong> pass<strong>in</strong>g of time. By look<strong>in</strong>g at my<br />

h<strong>and</strong>s I knew I had become old. All <strong>the</strong> men lost <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> me <strong>and</strong> turned to<br />

younger ones. I became old <strong>the</strong>refore I had to behave like an old woman. But this<br />

was not a bad th<strong>in</strong>g. After so many years, <strong>the</strong> teahouse had changed me. After so<br />

many years, I had built up a network <strong>and</strong> nobody dared to make trouble with me. I<br />

knew how to make those bastards yield with my softness, or with hardness<br />

concealed <strong>in</strong> softness. I saw through those cowards. They only knew to bully <strong>the</strong><br />

weak <strong>and</strong> fear <strong>the</strong> strong.”<br />

“And I found out that actually <strong>the</strong>re were two k<strong>in</strong>ds of capital that women<br />

could have: <strong>the</strong>ir body, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir language. As a young child, <strong>and</strong> throughout my life,<br />

I was never a good talker. But I learned how to talk <strong>in</strong> order to change my situation.<br />

Why are human be<strong>in</strong>gs superior to animals <strong>and</strong> birds Because <strong>the</strong> human be<strong>in</strong>g can<br />

talk. Sometimes th<strong>in</strong>gs could be settled down not by actions, but by how you put it<br />

<strong>in</strong>to words. A teahouse is also an <strong>in</strong>formation center of <strong>the</strong> county. I kept listen<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

<strong>the</strong> talk <strong>and</strong> came to know all about <strong>the</strong> residents, stories, or events from o<strong>the</strong>r places<br />

I had no hope of visit<strong>in</strong>g. I knew all about people <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> county. My <strong>in</strong>formation was<br />

much richer than <strong>the</strong> mayor’s. They said I was illiterate. But if someone read to me I<br />

Li/The F<strong>in</strong>al Confession of Mistress Wang 19

would underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> remember it. And I knew how to weave it <strong>in</strong>to my talk. What<br />

was <strong>the</strong> use of only know<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> dead words <strong>in</strong> books but noth<strong>in</strong>g else”<br />

“Slowly, I became a matchmaker. I forget when --maybe <strong>the</strong> third year after my<br />

husb<strong>and</strong>’s death. It doesn’t matter, it won’t be written <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> official history. But I<br />

really enjoyed it. It was not only for money—I had enough of that to last me out my<br />

days. It also gave me a sense of control: f<strong>in</strong>ally I got my day <strong>in</strong> which someone asked<br />

me for favour. I liked manipulat<strong>in</strong>g th<strong>in</strong>gs. Isn’t it good to arrange two peoples’ fates<br />

with your own delicate talk<strong>in</strong>g I did not have to take effort <strong>in</strong> watch<strong>in</strong>g o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

people’s secrets; <strong>the</strong>y were transparent to me. Noth<strong>in</strong>g could escape my eyes <strong>in</strong> this<br />

small county. Yes, a person is like a yard surrounded by a high wall. You are only<br />

perceived as <strong>the</strong> always-closed gate, <strong>the</strong> wall <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> top half of <strong>the</strong> trees, or <strong>the</strong><br />

graffiti on <strong>the</strong> wall. But I could get <strong>in</strong>to every corner of <strong>the</strong> yard. Those rich women,<br />

pretentious, condescend<strong>in</strong>g; once I knew <strong>the</strong>m better I stopped admir<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m. They<br />

were no better than me. Maybe nobody is better than you, if you know how to look<br />

at th<strong>in</strong>gs. Decorated with jade <strong>and</strong> gold <strong>and</strong> enclosed beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> wall, how could<br />

<strong>the</strong>y know about <strong>the</strong> outside world without talk<strong>in</strong>g with me, or with <strong>the</strong> nuns They<br />

could only imag<strong>in</strong>e hav<strong>in</strong>g affairs with o<strong>the</strong>rs, even with <strong>the</strong>ir bro<strong>the</strong>rs-<strong>in</strong>-law, sons<strong>in</strong>-law<br />

or servants. Yes, many times I knew <strong>the</strong>y really exercised <strong>the</strong>ir imag<strong>in</strong>ation.<br />

Only <strong>the</strong> stupid husb<strong>and</strong> did not know. But you also need to be careful when do<strong>in</strong>g<br />

bus<strong>in</strong>ess. Leave enough room to step backward. People did not want to trust my<br />

words. But I did not force <strong>the</strong>m; <strong>the</strong>y were just amused by <strong>the</strong>ir own imag<strong>in</strong>ation.<br />

People did not like me because I knew about <strong>the</strong>m. But <strong>the</strong>y couldn’t live without me.<br />

I’m <strong>the</strong> thread to weave <strong>the</strong>ir dreams toge<strong>the</strong>r. How can <strong>the</strong>y imag<strong>in</strong>e that <strong>the</strong>y<br />

belong to <strong>the</strong> same community without mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> secret of o<strong>the</strong>rs public”<br />

“Gradually my son grew up. Just look<strong>in</strong>g at his beard <strong>and</strong> broad shoulders<br />

satisfied me. I was expect<strong>in</strong>g this day but was also afraid of its com<strong>in</strong>g. He liked<br />

do<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess so much <strong>and</strong> he was always far away. Ano<strong>the</strong>r trouble was also<br />

com<strong>in</strong>g: to get him a wife. But what k<strong>in</strong>d of wife would she be I had been a<br />

matchmaker for such a long time <strong>and</strong> it should not have been difficult for me to<br />

select from <strong>the</strong> available girls. But it was only because I was a matchmaker that I<br />

could not make a choice. Just like a doctor cannot treat his family; a teacher cannot<br />

teach his children. And <strong>the</strong>re is no good woman at all <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> eyes of mo<strong>the</strong>r-<strong>in</strong>-law. I<br />

was lucky not hav<strong>in</strong>g a mo<strong>the</strong>r-<strong>in</strong>-law, but I do not underst<strong>and</strong> how a young woman<br />

can be so evil. A woman compet<strong>in</strong>g with me to cook for my son, ano<strong>the</strong>r woman<br />

wash<strong>in</strong>g his clo<strong>the</strong>s for him, <strong>and</strong> tak<strong>in</strong>g my son away to a place I did not know, all<br />

<strong>the</strong>se were <strong>the</strong> nightmares I had. Yes, nobody is reliable, even a son, needless to say a<br />

daughter-<strong>in</strong>-law. Yes, <strong>in</strong> this world only <strong>the</strong> sh<strong>in</strong>y silver is <strong>the</strong> most <strong>in</strong>timate to you.<br />

It’ll never betray you.”<br />

The Historical Project<br />

“Be<strong>in</strong>g Pan J<strong>in</strong>lian might be every woman’s nightmare if you see how she died.<br />

However, Ximen Q<strong>in</strong>g, I can say, is every man’s paradigm. Maybe you will say Wu<br />

Song. But Wu Song is not human. He lives <strong>in</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r world <strong>and</strong> this world is just his<br />

hotel. That’s why he does not like women, <strong>and</strong> why he can kill so cold-bloodedly.<br />

Any man who takes this world as home would care about his desire <strong>and</strong> get<br />

satisfaction. You may say that be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Emperor is every man’s biggest dream, but<br />

can an emperor really enjoy what he possesses, as Ximen Q<strong>in</strong>g did Most emperors<br />

20<br />

www.arts.auckl<strong>and</strong>.ac.nz/gjaps

ecome impotent under <strong>the</strong> pressure from <strong>in</strong>side <strong>and</strong> out. Maybe Ximen Q<strong>in</strong>g is <strong>the</strong><br />

real paradigm for men. Dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g, eat<strong>in</strong>g, man, woman, music, travel, silver, power,<br />

donkey-like organ, which one is not on your list Please do not argue with me. I have<br />

seen through men. The more I know about <strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong> more I hate <strong>the</strong>m, except for my<br />

son. But I need to use <strong>the</strong>m.”<br />

“You might have known, <strong>and</strong> all o<strong>the</strong>rs have known what I did to <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

People talk about it excitedly as if sipp<strong>in</strong>g a cup of tea. They call me a matchmaker, a<br />

madam. But people can only be seduced by <strong>the</strong>ir own imag<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y will<br />

follow <strong>the</strong>ir desires to death without notic<strong>in</strong>g. If <strong>the</strong>y do not want to do it <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> first<br />

place, how can I <strong>in</strong>terfere I just provided tactics <strong>and</strong> a third space for <strong>the</strong>m.”<br />

“I will tell you some stories beh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> story, my butterfly. I really enjoyed this<br />

case, though I got trapped <strong>in</strong> it. It was my biggest success, as well as my biggest<br />

failure. To br<strong>in</strong>g two married persons toge<strong>the</strong>r is more challeng<strong>in</strong>g than normal<br />

matchmak<strong>in</strong>g. You always need to consider failure first <strong>and</strong> make up your plan with<br />

your participants toge<strong>the</strong>r, tak<strong>in</strong>g environmental elements, scripts—what k<strong>in</strong>d of<br />

words you are go<strong>in</strong>g to use— <strong>and</strong> materials <strong>in</strong>to consideration. However, <strong>the</strong> result<br />

mostly depends on <strong>the</strong>ir performance. It is as subtle <strong>and</strong> difficult as comm<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g a<br />

battle. Remember how Zhuge Liang did <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> War of <strong>the</strong> Red Cliff He is <strong>the</strong><br />

paradigm <strong>in</strong> our profession.”<br />

“People say that I conspired with Ximen Q<strong>in</strong>g, No. I planned it with Pan J<strong>in</strong>lian,<br />

to seduce Ximen Q<strong>in</strong>g. When Pan J<strong>in</strong>lian <strong>and</strong> Wu Da first moved here, I knew at first<br />

sight how deep was Pan’s dissatisfaction with her situation. A young woman like her<br />

deserves a better partner. She looks like a doll. No! That’s too heavy. She is a<br />

butterfly fly<strong>in</strong>g so gently. If I were a man, I would def<strong>in</strong>itely catch her <strong>and</strong> pierce her<br />

heart so that she could never fly away 13 . One day Pan came to visit me <strong>and</strong> we talked<br />

for a long time. Gradually I knew her <strong>in</strong>tentions. There was a volcano <strong>in</strong> this woman<br />

but she did not know where <strong>the</strong> vent was. I knew this woman’s agony <strong>and</strong> ambition.<br />

It was at that moment that I knew how to help her. Our dialogue went like this:<br />

‘I can f<strong>in</strong>d you a satisfactory man, but you cannot be too anxious. By <strong>the</strong> way,<br />

what will you do to your husb<strong>and</strong>’<br />

‘What are you talk<strong>in</strong>g about I did not mean to… I do not know, I do not<br />

know.’<br />

‘Don’t be shy <strong>in</strong> front of me. Who am I I know what you want, even if you<br />

yourself do not.’<br />

‘He is not so potent. And see<strong>in</strong>g him makes me sick. I prefer stay<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> dark<br />

night although I do not want to sleep…’<br />

‘You know Ximen Q<strong>in</strong>g He is a successful man. He has everyth<strong>in</strong>g. I can f<strong>in</strong>d<br />

ways to let him come to my teahouse. And you just st<strong>and</strong> by your door often.<br />

Opportunities come for those who are prepared.’<br />

‘… …’<br />

‘Do you know how to deal with men Show <strong>the</strong>m someth<strong>in</strong>g, but do not<br />

approach <strong>the</strong>m. Your value will fall dramatically if you offer yourself to <strong>the</strong>m<br />

directly. The best way to conquer a man is to let him conquer you.’<br />

‘But… how…’<br />

‘I will br<strong>in</strong>g him here. When he passes your door, hit him slightly with your<br />

door curta<strong>in</strong>. Stay for a few seconds <strong>and</strong> firmly return to your home. That’s <strong>the</strong> bait<br />

for him.’<br />

Li/The F<strong>in</strong>al Confession of Mistress Wang 21

‘If he asks me about you, that means we can cont<strong>in</strong>ue our plan. Next step, I will<br />

make <strong>the</strong> whole plan seem like HIS plan with me, so you are <strong>in</strong>nocent of <strong>the</strong> whole<br />

th<strong>in</strong>g. And you need to perform well to be <strong>in</strong>nocent. I will tell him some strategies to<br />

use. Of course I will let him spend lots of money.’<br />

‘It sounds amaz<strong>in</strong>g. Where did you learn this I never knew this.’<br />

‘Let’s do it slowly <strong>and</strong> make it as tantaliz<strong>in</strong>g as possible. That will <strong>in</strong>crease<br />

your value <strong>in</strong> his eyes. ’<br />

‘How can I pay you back for this… You are always nice to me. And I am just a<br />

useless housewife…’<br />

‘Do not worry. We are neighbours <strong>and</strong> we need to support each o<strong>the</strong>r. If you<br />

can marry him, do not forget me when you enjoy your life. I will get my money from<br />

him <strong>and</strong> he will pay me will<strong>in</strong>gly for <strong>the</strong> present.’<br />

‘Of course. Of course. But how about <strong>the</strong> dwarf How can I face him if I…’<br />

‘I asked you at <strong>the</strong> beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g just for know<strong>in</strong>g your m<strong>in</strong>d. Do not worry about<br />

it now. Let’s wait <strong>and</strong> see. It is like cross<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> river by touch<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> stones on <strong>the</strong><br />

bottom. Isn’t it more stimulat<strong>in</strong>g when <strong>the</strong>re is a m<strong>in</strong>or danger <strong>in</strong> our plan’<br />

As you know, our plan was carried out. I got my money. The money itself is<br />

not important. But by see<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> aura of <strong>the</strong> sh<strong>in</strong>y silver you can imag<strong>in</strong>e you are<br />

more powerful <strong>and</strong> you words get better endorsement. Sometimes, sitt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> front of<br />

<strong>the</strong> door to guard for <strong>the</strong>m, listen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> imag<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g what <strong>the</strong>y were do<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> my bed,<br />

I thought about myself. Too many th<strong>in</strong>gs had gone forever before I had a chance to<br />

enjoy <strong>the</strong>m. I am proud of <strong>the</strong>m <strong>and</strong> I’m jealous too…”<br />

“I am still feel<strong>in</strong>g no regret for what I did. Ximen Q<strong>in</strong>g is a tall tree <strong>and</strong> Pan<br />

J<strong>in</strong>lian is <strong>the</strong> very Ch<strong>in</strong>ese wisteria ( 紫 藤 ) born to take root <strong>in</strong> this tree. That dwarf<br />

Wu Da, he was too short for a plant like Pan to grow on. I have to admit that he was<br />

a good guy. He was satisfied with what he had <strong>and</strong> what he did. Everyday he passed<br />

by my door, greet<strong>in</strong>g me with smile, no matter if I answered back or not. Is <strong>the</strong>re any<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r guy <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> county who can endure his wife’s curse <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>fidelity without<br />

say<strong>in</strong>g a word but h<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g a cup of warm tea to her with smile But he is too good<br />

for his short figure. You might say, physical appearance does not matter, <strong>and</strong> people<br />

can construct <strong>the</strong>ir identities however <strong>the</strong>y like. 14 But how can you get out of <strong>the</strong> trap<br />

of your body Call it a house or a prison. No way! Yes, I feel pity for him. Everybody<br />

pitied him <strong>and</strong> made fun of him:<br />

‘Hi! Wu Da. Your pies are not tasty. Your wife has two better steamed buns.<br />

Can<br />

I<br />

buy <strong>the</strong>m from her’<br />

‘Be careful my bro<strong>the</strong>r, do not let my bro<strong>the</strong>r Wu Song hear this…’ So was his<br />

consideration. Maybe it was because he was so weak <strong>and</strong> short that he had to be<br />

good. Could he kill a chick I prefer be<strong>in</strong>g a street woman to liv<strong>in</strong>g with him, if I<br />

could make my own choice. Pan J<strong>in</strong>lian — people called her Golden Lotus — was a<br />

gift to him which he did not deserve.”<br />

“But how many times have <strong>the</strong> calculator <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> schemer forgotten to<br />