WT_2007_02: PROFILE: PERRELET

WT_2007_02: PROFILE: PERRELET

WT_2007_02: PROFILE: PERRELET

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

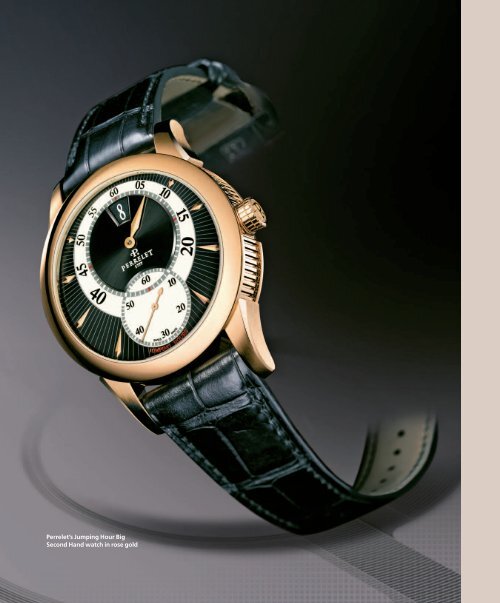

Perrelet’s Jumping Hour Big<br />

Second Hand watch in rose gold

Left: This antique postcard shows<br />

an engraving of Abraham-Louis<br />

Perrelet by Charles-Samuel<br />

Girardet. Below: An 18thcentury<br />

pocket watch with<br />

automatic movement attributed<br />

to Abraham-Louis Perrelet<br />

Reviving Perrelet<br />

BY NORMA BUCHANAN<br />

Once you acquire a grand old Swiss watch name, how do you<br />

breathe life into it We asked Herbert Arni, the head of<br />

Perrelet SA.<br />

For today’s watch entrepreneurs, a good<br />

man is hard to find. Especially a good<br />

watchmaker, long dead (the longer the<br />

better), who can serve as a creditable “founding<br />

father” for a modern-day watch brand.<br />

Watch companies scour horological archives<br />

and prowl Swiss cemeteries, reading headstone<br />

inscriptions, in search of such men.<br />

So you can imagine how happy Miguel Rodriquez<br />

was when he heard that Abraham-<br />

Louis Perrelet’s name was on the market. Rodriguez,<br />

owner of the mid-priced Festina<br />

brand, is trying to gain a foothold in the luxury<br />

segment of the Swiss-watch industry. So, in<br />

2004, when Perrelet’s then-owner decided to<br />

sell the brand, Rodriguez snapped it up.<br />

Perrelet is one of the most famous watchmakers<br />

who ever lived. As nearly every watch<br />

aficionado knows, he invented the self-winding<br />

watch. The rotor he developed, or a close<br />

facsimile of it, spins tirelessly on the wrists of<br />

millions of consumers (usually visible through a<br />

glass caseback), powering the vast majority of<br />

luxury mechanical watches made today.<br />

Rodriguez bought the Perrelet brand from<br />

Flavio Audemars, who in 1993 established the<br />

Neuchâtel firm Perrelet SA to develop and market<br />

Perrelet wristwatches. (Audemars has no<br />

connection to the Audemars Piguet watch firm.)<br />

Rodriguez added Perrelet, which was virtually<br />

April <strong>2007</strong> WatchTime 123

<strong>PROFILE</strong>: <strong>PERRELET</strong><br />

Herbert Arni, CEO of Perrelet SA<br />

dead — it had some distribution in Russia, but<br />

almost none anywhere else — to a trio of<br />

brands, L. Leroy, Joseph Chevalier and Berney-<br />

Blondeau, that he had already assembled in a<br />

holding company called the H5 Groupe.<br />

“H5” is short for “Holding Hispano Helvétique<br />

de Haute Horlogerie.” “Hispano” refers to<br />

the fact that Rodriguez is Spanish; Festina is<br />

headquartered in Barcelona. “Helvétique”<br />

comes from “Helvetia,” the Latin name for<br />

Switzerland.<br />

Rodriguez chose watch-industry veteran<br />

Herbert Arni, whose prior posts included jobs<br />

with Heuer, Omega, Eterna, and Versace, to<br />

head Perrelet SA and the holding company,<br />

both based in Bienne. By spring of 2005, in<br />

time for Baselworld, the new Perrelet line was<br />

set to go.<br />

Arni’s mission has been to capitalize on the<br />

strength of the Perrelet name, which he describes<br />

as “an unbelievable asset.” To do that,<br />

he’s had to start from scratch, developing a<br />

new product line and a new way of connecting<br />

Perrelet the brand to Perrelet the man.<br />

The Right Spin<br />

It was the latter task that required the most ingenuity.<br />

After all, winding rotors are standard<br />

equipment for mechanical watches. Simply<br />

making all Perrelet watches automatics would<br />

do nothing to highlight the brand’s link to the<br />

inventor of that now ubiquitous device. Arni<br />

needed another way to make the Perrelet point.<br />

The previous owner had his own solution:<br />

a device consisting of two rotors, connected<br />

to each other. One is in the traditional position,<br />

under the movement; the other is on the<br />

dial side of the movement, visible, and sitting<br />

in a recessed circle. The bottom rotor winds<br />

the mainspring. The dial-side rotor is purely<br />

for show. Its spinning does nothing to wind<br />

the mainspring; it’s there only as “an homage<br />

to Mr. Perrelet,” Arni says.<br />

To many people’s surprise, Arni ditched the<br />

signature double-rotor (although not entirely:<br />

it lives on in two models, one round, the other<br />

a tonneau). For one thing, it was tricky to manufacture<br />

and made the watches too expensive.<br />

Arni wanted to keep Perrelet’s prices out of the<br />

stratosphere (they start at $2,850 for a big-date<br />

model with small seconds subdial). Under the<br />

Audemars ownership, the brand had been<br />

priced higher. Furthermore, Arni was leery of<br />

taking what he calls a “mono-product” approach<br />

to the brand by relying exclusively on<br />

the appeal of the double rotor.<br />

How else could he create a Perrelet-related<br />

identity for Perrelet The company’s designers<br />

came up with an answer: a way of decorating<br />

the movement that incorporates the winding<br />

rotor. The movement’s bridges are engraved<br />

with what the company calls<br />

the “Perrelet tapestry,” an elaborate<br />

pattern of interlocked<br />

“P’s.” In order to make the<br />

tapestry visible, the rotor is<br />

fitted with transparent<br />

glass. The center of the<br />

rotor bears a large “P”<br />

on a solid circle of metal<br />

that hides what Arni<br />

regards as the least attractive<br />

part of the<br />

movement. The rotor is<br />

manufactured by DTH,<br />

or Dubois Technique<br />

Horlogère, a maker of<br />

components and modules,<br />

Five Minute<br />

Repeater in<br />

rose gold<br />

owned by<br />

Rodriguez and<br />

located in the Vallée<br />

de Joux. “The goal of<br />

this exercise is that in one,<br />

two or three years, the consumer<br />

turns the watch over and<br />

says ‘This must be a Perrelet, because<br />

only they do this,’” Arni says.<br />

The Perrelet tapestry-cum-transparent rotor<br />

was one way to distinguish the brand, but Arni<br />

wanted others. He knew that if the brand were<br />

to claim to be the spiritual heir of Abraham-<br />

Louis Perrelet, simply sticking a standard automatic<br />

movement in a case would not suffice. “If<br />

you are the inventor of the automatic, you cannot<br />

just buy a [Valjoux] 2892, put it in a nice case<br />

and say, ‘This is an automatic watch, and, by the<br />

way, I am the inventor of this.’<br />

“On the other hand, we did not have the<br />

A current Perrelet movement with the<br />

“Perrelet tapestry” visible through the<br />

transparent winding rotor<br />

124 WatchTime April <strong>2007</strong>

<strong>PROFILE</strong>: <strong>PERRELET</strong><br />

NEXT UP: L. LEROY<br />

Now that Perrelet is off the launching pad, its<br />

owner, the H5 Groupe, is getting another<br />

brand ready.<br />

It’s called L. Leroy (pronounced “le WAH”).<br />

Its origins stretch back to a French watchmaking<br />

family that rose to prominence in the<br />

18th century. (It is not to be confused with<br />

the le Roy family whose most famous member,<br />

Pierre, is credited with inventing the<br />

detent escapement for use in marine<br />

chronometers.) The L. Leroy of the brand’s<br />

name is Louis Leroy, who joined the family<br />

firm in 1879.<br />

H5 bought the L. Leroy brand in 2004, just<br />

before buying Perrelet. L. Leroy was still making<br />

watches, but they were sold in a tiny<br />

number of stores. Annual production was<br />

only about 400 pieces per year. As it did with<br />

Perrelet, H5 is revamping both the products<br />

and the distribution, and plans to re-launch<br />

the brand at the end of this year, says Herbert<br />

Arni, the head of H5. L. Leroy will be expensive,<br />

in the range of, say, Breguet, and very<br />

narrowly distributed. The collection will be introduced<br />

first in Italy, Switzerland, France and<br />

Spain. Other markets will follow later.<br />

Next year, L Leroy will get its own exclusive<br />

movement, developed and manufactured by<br />

H5’s sister company, DTH (Dubois Technique<br />

Horlogère), which makes modules and movement<br />

components, for H5 and other companies,<br />

in the Vallée de Joux. “It isn’t possible to<br />

put Leroy on the market without it having its<br />

own movement,” Arni says<br />

Both H5 and DTH are owned by Spanish<br />

watch entrepreneur Miguel Rodriguez. His<br />

Barcelona-based Festina Group has a stable of<br />

mid-priced, mostly quartz brands: Festina, Lotus,<br />

Calypso, Jaguar and Candino. Over the<br />

past several years, Rodriguez has been on a<br />

shopping spree, buying up well-known,<br />

and not-so-well known, brand names, intent<br />

on becoming a player in the world of<br />

haute horlogerie. He now has four brands<br />

under the H5 umbrella.<br />

The two others are Berney-<br />

Blondeau and Joseph Chevalier, the<br />

former an old brand from the Vallée<br />

de Joux, the latter named for a<br />

19th-century Geneva watchmaker.<br />

Both will spend a while “in<br />

the fridge,” Arni says. Look for<br />

them in a few years, maybe<br />

around 2010.<br />

money, the time or the capacity to make our own<br />

movement,” Arni says. “This is an exercise of five<br />

years with three to five million [Swiss francs] up<br />

front. And then you don’t know if it works.”<br />

Arni’s solution is to use ETA movements,<br />

assembled not by ETA but by a third party,<br />

combined with modules made exclusively for<br />

Perrelet by companies including Dubois<br />

Dépraz and DTH.<br />

Simple Complications<br />

His strategy in developing new products is to<br />

incorporate just one or two complications in a<br />

watch, making those complications as userfriendly<br />

as possible. “We are not in the gadget<br />

business, combining an alarm with a tripletime-zone<br />

watch and adding a chronograph,<br />

which nobody can read and no sales staff can<br />

sell,” Arni says. The designers focused on readability,<br />

so that nearly all the date displays are<br />

so-called “big dates,” and the power-reserve<br />

indicators are far larger than on most watches.<br />

The line contains 14 distinct models (there<br />

are some 300 distinct styles, if you include variations<br />

in case materials, straps, etc.). Several of<br />

the steel models are priced at under $5,000:<br />

the steel chronograph with big date is $4,250;<br />

the steel double rotor is $3,600. At the top of<br />

the price range are such pieces as the limitededition<br />

platinum automatic tourbillon, for<br />

$90,000 (rose-gold and steel tourbillons are<br />

$60,000 and $52,500, respectively).<br />

Last year, the company introduced a fiveminute<br />

repeater ($29,900 in rose gold) and a<br />

jumping hour ($5,575 in steel,<br />

$15,675 in palladium and $17,000 in<br />

gold). The company also added a<br />

large-moonphase watch to its<br />

women’s collection. As you might<br />

guess, the women’s Perrelet<br />

models are all automatics.<br />

They’re priced from about<br />

$5,000 to $10,000.<br />

The five-minute repeater<br />

was something of a<br />

pet project for Arni, who<br />

The Double Rotor features a<br />

second rotor on the dial,<br />

strictly for show.<br />

COSC-certified automatic flying tourbillon in<br />

stainless steel<br />

believes repeaters are the next wave in complications.<br />

Perrelet came late to the tourbillon party<br />

with its COSC-certified automatic chronometer<br />

tourbillon, but intends to get in on the<br />

ground floor with five-minute repeaters, which<br />

offer a more affordable alternative to minute repeaters.<br />

Perrelet’s version, like the new jumping<br />

hour, incorporates a Dubois Dépraz module.<br />

Perrelet watches are styled in what Arni calls<br />

a “classic-contemporary” mode. The sides of<br />

the case bear a modern-looking pattern of vertical<br />

striations, and most of the dials are decorated<br />

with a striped pattern emanating from<br />

the center of the dial.<br />

The Toast of Le Locle<br />

In developing the new products, Perrelet SA<br />

got little help either from extant watches made<br />

by Perrelet himself or from historical documents.<br />

Other brands bearing the names of famous<br />

watchmakers, brands like Patek Philippe,<br />

Vacheron Constantin, Breguet and Audemars<br />

Piguet, have a wealth of antique and vintage<br />

watches, as well as archival material, to draw<br />

on. Perrelet has next to nothing.<br />

One reason is that, following the custom of<br />

Abraham-Louis Perrelet’s time (he lived from<br />

1729 to 1826) and his location (canton<br />

Neuchâtel), he did not sign his watches. The<br />

126 WatchTime April <strong>2007</strong>

<strong>PROFILE</strong>: <strong>PERRELET</strong><br />

SELF-WINDING THROUGH<br />

THE CENTURIES<br />

An automatic movement from an 18thcentury<br />

watch attributed to Abraham-<br />

Louis Perrelet<br />

A view of the movement inside a Harwood<br />

watch from the 1920s<br />

A view of the rotor in a Rolex Oyster from<br />

the 1930s<br />

Abraham-Louis Perrelet would be surprised, and no<br />

doubt delighted, if he walked into a watch store<br />

today. There, in showcase after showcase, he’d see<br />

watches fitted with the automatic winding system<br />

— many of them showing off their elaborately decorated<br />

rotors through transparent casebacks —<br />

that he invented some 237 years ago. Perrelet,<br />

described by one author as a “retiring inventor of<br />

genius,” was a modest homebody who spent his<br />

entire life in the watchmaking town of Le Locle. It’s<br />

safe to say he had no inkling of what would<br />

become of his winding rotor.<br />

In fact, Perrelet didn’t invent the concept of<br />

winding with an oscillating weight. It probably<br />

dates back to the 17th century. But early experiments<br />

in self-winding never amounted to much. A<br />

19th-century book, Histoire de l’horlogerie, by<br />

Pierre Dubois, describes them as follows: “…The<br />

mechanism of these timepieces was so defective<br />

and worked so badly, that these early perpetual<br />

watches soon came to be considered mere<br />

baubles, mere fashionable novelties.”<br />

Perrelet is universally credited with being the first<br />

to make an automatic-winding system that actually<br />

worked. Two of the foremost authorities on the<br />

subject, Alfred Chapuis and Eugène Jaquet, authors<br />

of The History of the Self-Winding Watch, write,<br />

“…the manufacture of the first really complete and<br />

technically sound self-winder can be attributed to<br />

Abraham-Louis Perrelet.”<br />

He used two types of winding weights in his automatic<br />

watches, the authors write. One was oval or<br />

round, and swung back and forth on a pivot in the<br />

manner of a pendulum (except that its swings were<br />

halted in either direction by banking pins). The<br />

other, familiar to watch owners today, used a<br />

semicircular, fan-shaped rotor that spun around<br />

pieces attributed to him have been identified<br />

through detective work. Furthermore, Abraham-Louis<br />

Perrelet did not found a company,<br />

so there was none to keep his name in the<br />

public eye through successive generations.<br />

His grandson, Louis-Frédéric Perrelet,<br />

achieved some celebrity as the official watchmaker<br />

to the French kings Louis XVIII, Charles<br />

X and Louis-Philippe, and one emperor,<br />

Napoleon III. He is also known for having<br />

patented a split-seconds chronograph in<br />

1827. But after he died, in 1854, the Perrelet<br />

name entered watchmaking oblivion.<br />

In Abraham-Louis’s day, though, it echoed<br />

through the Jura Mountains. He was born in<br />

Le Locle on June 9, 1729, the son of a wellknown<br />

maker of watchmaking tools. (His first<br />

name was actually spelled “Abram-Louis” in<br />

the Neuchâtel manner, as was, originally, the<br />

first name of Abraham-Louis Breguet, and it is<br />

this spelling that is most often seen in old horological<br />

history books. The names of both<br />

watchmakers later morphed into the more<br />

common “Abraham.”)<br />

Perrelet made his first automatic watch<br />

sometime around 1770. The renowned horological<br />

historians Alfred Chapuis and Eugène<br />

Jaquet write in their book, The History of the<br />

Self-Winding Watch, that Perrelet used two<br />

different types of oscillating weights in his au-<br />

128 WatchTime April <strong>2007</strong>

360 degrees on a center pivot, winding the watch<br />

regardless of which way it was turning.<br />

During Perrelet’s lifetime and some decades<br />

thereafter, it was the former system that prevailed.<br />

Breguet refined the back-and-forth mechanism and<br />

fit it into his famous perpetuelle watches, and other<br />

watchmakers, including Louis Recordon and the<br />

Jaquet-Droz firm, also adopted it. Historians think<br />

the reason the spinning rotor was abandoned was<br />

that it did not generate enough power. In those<br />

days, all watches were, of course, pocket or pendant<br />

watches, and were not subjected to as much<br />

motion as wristwatches are.<br />

In their first decades, automatic watches made<br />

quite a splash and were produced in large numbers.<br />

But even the back-and-forth type of self-winders<br />

presented problems. If not expertly manufactured,<br />

they didn’t work. They were very expensive to<br />

produce, and few people knew how to repair them.<br />

And they were big: the winding weight added appreciable<br />

thickness in an era when thin watches<br />

were definitely in.<br />

Around 1840, the self-winding mechanism<br />

received a near-fatal blow: the introduction of keyless<br />

winding, which eliminated automatic winding’s<br />

biggest reason for being. Self-winding had been<br />

invented chiefly because key winding was such a<br />

nuisance. Not only did the watch owner need to<br />

keep his winding key with him, he risked chipping<br />

or scratching his watch’s dial whenever he inserted<br />

the key into the key aperture. Furthermore, this<br />

hole provided an entry point for dirt and dust. So<br />

when key winding disappeared, so too, for all<br />

practical purposes, did automatic winding.<br />

Until the wristwatch came along. When, during<br />

World War I, soldiers began wearing wristwatches<br />

in large numbers, automatic winding once again<br />

tomatic watches. One was a banked weight,<br />

later adopted by Breguet, whom he knew and<br />

to whom he sold some watches; the other was<br />

a spinning rotor like that used today. Perrelet’s<br />

watches were extremely popular during his<br />

lifetime, and helped make him something of a<br />

horological celebrity.<br />

So did his other accomplishments. Chapuis<br />

and Jaquet describe him as a craftsman<br />

par excellence, celebrated throughout canton<br />

Neuchâtel. He was the first Le Locle watchmaker<br />

to work on cylinder escapements and<br />

on such complications as calendars and equation<br />

of time devices, they write. They quote a<br />

book entitled Biographie Neuchâteloise dehad<br />

a raison d’etre. Wristwatches were exposed<br />

to much more dirt and dust than pocket<br />

watches because they were unsheltered from<br />

the elements. This dirt entered the watch<br />

through the winding-stem hole.<br />

The problem was especially acute in trench<br />

warfare. In the 1920s, John Harwood, a British<br />

watchmaker who had fought in the war,<br />

resurrected Perrelet’s old concept of a centrally<br />

pivoted winding weight and applied it to a<br />

wristwatch. Because wristwatches are subjected<br />

to more motion than pocket watches, the rotor<br />

concept would work in them, he realized.<br />

Harwood’s watch had no crown; the owner set<br />

the time by turning the bezel. There was<br />

therefore no way for dirt to get into the case.<br />

Harwood’s watches may have been dirt-free,<br />

but several technical flaws nonetheless doomed<br />

them. The biggest was the shocks that shook<br />

the movement every time the rotor hit one of<br />

the banking springs. The Harwood watch was<br />

abandoned in just a few years.<br />

In 1931, Rolex succeeded where Harwood<br />

had failed. It adapted Perrelet’s centrally pivoted<br />

rotor in a different way than Harwood had:<br />

instead of the rotor moving through an arc, and<br />

being stopped on either side by banking<br />

springs, the rotor swung around freely in either<br />

direction, just like Perrelet’s rotor had done. This<br />

eliminated the shocks that had plagued<br />

Harwood’s watches. (Rolex had solved the dirt<br />

problem five years earlier by introducing the first<br />

truly impermeable watch case, which it incorporated<br />

in its Oyster models.)<br />

Today’s automatic watches use essentially the<br />

same system. Perrelet, modest though he was,<br />

would surely be proud.<br />

scribing him as “the master of all watchmakers<br />

of Le Locle.” Whenever other Le Locle<br />

watchmakers had a problem they couldn’t<br />

solve, they would say to each other, “Let’s go<br />

to old Perrelet,” according to the Biographie.<br />

And old he became, making entire watches<br />

from scratch well into his 90s. He completed a<br />

lever-escapement watch at age 95. Earlier in<br />

his career, the town of Neuchâtel had tried to<br />

lure him away from Le Locle, but to no avail.<br />

He died there at 97.<br />

Although he left few watches to remember<br />

him by, we have plenty of evidence of his<br />

ingenuity. You need look no further than<br />

your wrist.<br />

■<br />

April <strong>2007</strong> WatchTime 129