The Ontological Argument for the Existence of God - Anselm

The Ontological Argument for the Existence of God - Anselm

The Ontological Argument for the Existence of God - Anselm

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

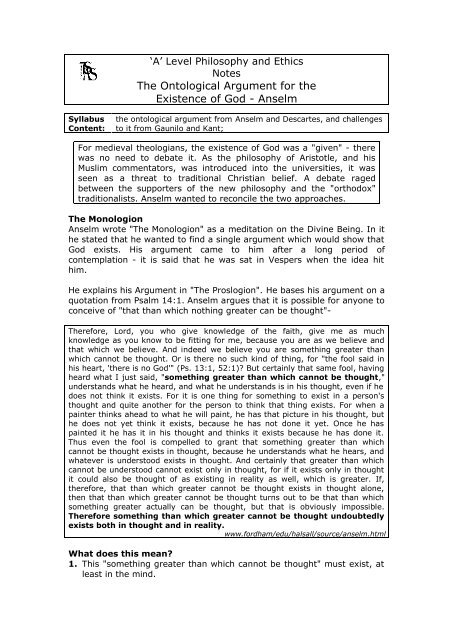

‘A’ Level Philosophy and Ethics<br />

Notes<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ontological</strong> <strong>Argument</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Existence</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>God</strong> - <strong>Anselm</strong><br />

Syllabus<br />

Content:<br />

<strong>the</strong> ontological argument from <strong>Anselm</strong> and Descartes, and challenges<br />

to it from Gaunilo and Kant;<br />

For medieval <strong>the</strong>ologians, <strong>the</strong> existence <strong>of</strong> <strong>God</strong> was a "given" - <strong>the</strong>re<br />

was no need to debate it. As <strong>the</strong> philosophy <strong>of</strong> Aristotle, and his<br />

Muslim commentators, was introduced into <strong>the</strong> universities, it was<br />

seen as a threat to traditional Christian belief. A debate raged<br />

between <strong>the</strong> supporters <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> new philosophy and <strong>the</strong> "orthodox"<br />

traditionalists. <strong>Anselm</strong> wanted to reconcile <strong>the</strong> two approaches.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Monologion<br />

<strong>Anselm</strong> wrote "<strong>The</strong> Monologion" as a meditation on <strong>the</strong> Divine Being. In it<br />

he stated that he wanted to find a single argument which would show that<br />

<strong>God</strong> exists. His argument came to him after a long period <strong>of</strong><br />

contemplation - it is said that he was sat in Vespers when <strong>the</strong> idea hit<br />

him.<br />

He explains his <strong>Argument</strong> in "<strong>The</strong> Proslogion". He bases his argument on a<br />

quotation from Psalm 14:1. <strong>Anselm</strong> argues that it is possible <strong>for</strong> anyone to<br />

conceive <strong>of</strong> "that than which nothing greater can be thought"-<br />

<strong>The</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, Lord, you who give knowledge <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> faith, give me as much<br />

knowledge as you know to be fitting <strong>for</strong> me, because you are as we believe and<br />

that which we believe. And indeed we believe you are something greater than<br />

which cannot be thought. Or is <strong>the</strong>re no such kind <strong>of</strong> thing, <strong>for</strong> "<strong>the</strong> fool said in<br />

his heart, '<strong>the</strong>re is no <strong>God</strong>'" (Ps. 13:1, 52:1) But certainly that same fool, having<br />

heard what I just said, "something greater than which cannot be thought,"<br />

understands what he heard, and what he understands is in his thought, even if he<br />

does not think it exists. For it is one thing <strong>for</strong> something to exist in a person's<br />

thought and quite ano<strong>the</strong>r <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> person to think that thing exists. For when a<br />

painter thinks ahead to what he will paint, he has that picture in his thought, but<br />

he does not yet think it exists, because he has not done it yet. Once he has<br />

painted it he has it in his thought and thinks it exists because he has done it.<br />

Thus even <strong>the</strong> fool is compelled to grant that something greater than which<br />

cannot be thought exists in thought, because he understands what he hears, and<br />

whatever is understood exists in thought. And certainly that greater than which<br />

cannot be understood cannot exist only in thought, <strong>for</strong> if it exists only in thought<br />

it could also be thought <strong>of</strong> as existing in reality as well, which is greater. If,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, that than which greater cannot be thought exists in thought alone,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n that than which greater cannot be thought turns out to be that than which<br />

something greater actually can be thought, but that is obviously impossible.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e something than which greater cannot be thought undoubtedly<br />

exists both in thought and in reality.<br />

www.<strong>for</strong>dham/edu/halsall/source/anselm.html<br />

What does this mean<br />

1. This "something greater than which cannot be thought" must exist, at<br />

least in <strong>the</strong> mind.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ontological</strong> <strong>Argument</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Existence</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>God</strong><br />

<strong>Anselm</strong><br />

2. But if it exists only in <strong>the</strong> mind <strong>the</strong>n it is inferior to anything that exists<br />

both in <strong>the</strong> mind and in reality.<br />

3. It must <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e be that <strong>the</strong> thing than which nothing greater can be<br />

thought exists both in <strong>the</strong> mind and in reality.<br />

4. <strong>The</strong> most perfect conceivable being must exist in reality as well as in<br />

<strong>the</strong> mind.<br />

This argument hinges on <strong>the</strong> following points:<br />

<strong>The</strong> real will always be greater than <strong>the</strong> imaginary<br />

(compare this debate with Ally McBeal's struggle with<br />

her feelings about <strong>the</strong> perfect "meaningful o<strong>the</strong>r"!)<br />

That <strong>God</strong> is <strong>the</strong> "greater thing" that <strong>Anselm</strong> is talking <strong>of</strong>.<br />

This leads to <strong>the</strong> second stage <strong>of</strong> <strong>Anselm</strong>'s argument, that if <strong>God</strong> is <strong>the</strong><br />

greatest thing imaginable, he must exist - if he didn't, something<br />

greater could be imagined which actually did exist!<br />

In <strong>the</strong> third chapter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Proslogion, he argues that <strong>for</strong> <strong>God</strong>, existence is<br />

necessary.<br />

In fact, it so undoubtedly exists that it cannot be thought <strong>of</strong> as not existing. For one can think <strong>the</strong>re<br />

exists something that cannot be thought <strong>of</strong> as not existing, and that would be greater than something<br />

which can be thought <strong>of</strong> as not existing. For if that greater than which cannot be thought can be thought<br />

<strong>of</strong> as not existing, <strong>the</strong>n that greater than which cannot be thought is not that greater than which cannot<br />

be thought, which does not make sense. Thus that than which nothing can be thought so undoubtedly<br />

exists that it cannot even be thought <strong>of</strong> as not existing.<br />

And you, Lord <strong>God</strong>, are this being. You exist so undoubtedly, my Lord <strong>God</strong>, that you cannot even be<br />

thought <strong>of</strong> as not existing. And deservedly, <strong>for</strong> if some mind could think <strong>of</strong> something greater than you,<br />

that creature would rise above <strong>the</strong> creator and could pass judgment on <strong>the</strong> creator, which is absurd. And<br />

indeed whatever exists except you alone can be thought <strong>of</strong> as not existing. You alone <strong>of</strong> all things most<br />

truly exists and thus enjoy existence to <strong>the</strong> fullest degree <strong>of</strong> all things, because nothing else exists so<br />

undoubtedly, and thus everything else enjoys being in a lesser degree. Why <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e did <strong>the</strong> fool say in<br />

his heart "<strong>the</strong>re is no <strong>God</strong>," since it is so evident to any rational mind that you above all things exist<br />

Why indeed, except precisely because he is stupid and foolish<br />

www.<strong>for</strong>dham/edu/halsall/source/anselm.html<br />

<strong>Anselm</strong> aims to define <strong>God</strong> in such a way as to make it impossible to<br />

conceive <strong>of</strong> Him as not existing.<br />

"Since <strong>God</strong> in his infinite<br />

• What we cannot conceive <strong>of</strong> as not perfection is not limited in or by<br />

existing must be greater than what time, <strong>the</strong> twin possibilities <strong>of</strong> his<br />

we can conceive <strong>of</strong> as not existing.<br />

having ever some to exist and <strong>of</strong><br />

his ever ceasing to exist are alike<br />

• It would be absurd to propose that<br />

excluded, and his non-existence<br />

<strong>the</strong> greatest thing that can be<br />

is rendered impossible".<br />

thought <strong>of</strong> did not exist, because Hick, J. Philosophy <strong>of</strong> Religion,<br />

<strong>the</strong>re would be something greater in Prentice Hall, p17<br />

reality than <strong>the</strong> thought first proposed.<br />

Assuming you can accept <strong>Anselm</strong>’s definition <strong>of</strong> <strong>God</strong> as “<strong>the</strong> greatest thing<br />

that can be thought” If we can hold <strong>the</strong> concept <strong>of</strong> <strong>God</strong> in our minds, <strong>God</strong><br />

2

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ontological</strong> <strong>Argument</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Existence</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>God</strong><br />

<strong>Anselm</strong><br />

must exist in reality, since that which exists in reality is always greater<br />

that that which exists only in <strong>the</strong> mind.<br />

Criticisms <strong>of</strong> <strong>Anselm</strong>'s <strong>Argument</strong><br />

A monk named Gaunilo argued that, if what <strong>Anselm</strong> said was true, <strong>the</strong>n<br />

<strong>the</strong> same could be said to prove <strong>the</strong> existence <strong>of</strong> an<br />

imaginary island. His reply was called "In Behalf <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Fool".<br />

• You think <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> perfect island.<br />

• Since it is perfect, it must exist, or it would be<br />

inferior to <strong>the</strong> grottiest island on <strong>the</strong> map.<br />

<strong>Anselm</strong> himself provided a reply.<br />

He pointed out that an island is a finite, limited thing.<br />

When one person imagines a "perfect" island, <strong>the</strong>re will always be<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r "perfect" islands.<br />

<strong>The</strong> "thought than which nothing greater can be thought" is unique.<br />

<strong>Anselm</strong> believed that Gaunilo's argument was defeated by his own<br />

proposition <strong>of</strong> "necessary existence".<br />

Necessary <strong>Existence</strong><br />

In “Teach Yourself Philosophy <strong>of</strong> Religion”, Mel Thompson points out<br />

that <strong>the</strong>re is a distinction between logical and factual necessity.<br />

• If "<strong>God</strong> exists" is a logical necessity (i.e. if it is an analytic<br />

statement, [true within itself] <strong>the</strong>n "<strong>God</strong> does not exist" would be<br />

self-contradictory.<br />

• If "<strong>God</strong> exists" is a factual necessity, it implies that it is impossible<br />

<strong>for</strong> things to be as <strong>the</strong>y are if <strong>God</strong> did not exist, and <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e that it<br />

is actually not possible <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>re to be no <strong>God</strong>.<br />

Thompson, M. Teach Yourself Philosophy <strong>of</strong> Religion, Hodder, p92<br />

<strong>The</strong> philosopher holds <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> a “Greatest Being” in his mind. Simply<br />

knowing about this “Greatest Being” does not mean that it has to exist.<br />

All that has been established is that if I can think <strong>of</strong> such a being, <strong>the</strong>n it<br />

is possible <strong>for</strong> it to exist. <strong>Anselm</strong> goes on to try to argue that it is<br />

necessary <strong>for</strong> <strong>God</strong> to exist.<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, if it can be thought <strong>of</strong> at all, it must necessarily exist. For no one<br />

who denies or doubts <strong>the</strong> existence <strong>of</strong> "a being greater than which cannot be<br />

thought <strong>of</strong>" denies or doubts that, if it did exist, it would be impossible <strong>for</strong> it not<br />

to exist ei<strong>the</strong>r in reality or in <strong>the</strong> mind. O<strong>the</strong>rwise it would not be "a being greater<br />

than which cannot be thought <strong>of</strong>." But whatever can be thought <strong>of</strong> yet does not<br />

actually exist, could, if it did come to exist, not existence again in reality and in<br />

<strong>the</strong> mind. That is why, if it can even be thought <strong>of</strong>, "a being greater than which<br />

cannot be thought <strong>of</strong>" cannot be nonexistent.<br />

www.<strong>for</strong>dham/edu/halsall/source/anselm.htm<br />

• In order <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> concept held in <strong>the</strong> philosopher’s mind to be “<strong>the</strong><br />

greatest being”, it has to be <strong>the</strong> greatest thing in reality.<br />

3

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Ontological</strong> <strong>Argument</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Existence</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>God</strong><br />

<strong>Anselm</strong><br />

• If <strong>the</strong> philosopher had thought <strong>of</strong> this greatest being, and it did not<br />

exist, <strong>the</strong>n (following <strong>the</strong> first part <strong>of</strong> <strong>Anselm</strong>’s argument) it would<br />

have to come into existence.<br />

• If it can come into existence, it can also go out <strong>of</strong> existence – it is a<br />

part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> contingent world, and not <strong>the</strong> greatest thing that can be<br />

thought <strong>of</strong>.<br />

If this “greatest being” that you have been thinking <strong>of</strong> is actually <strong>the</strong><br />

greatest being, it must exist. <strong>The</strong> Greatest Thing must be so perfect that<br />

it cannot be conceived <strong>of</strong> as not existing.<br />

<strong>God</strong>’s <strong>Existence</strong> is <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e Necessary<br />

But let us suppose that it does not exist (if it is even possible to suppose as<br />

much). Whatever can be thought <strong>of</strong> yet does not exist, even if it should<br />

come into existence, would not be "a being greater than which cannot be<br />

thought <strong>of</strong>." Thus "a being greater than which cannot be thought <strong>of</strong>" would<br />

not be "a being greater than which cannot be thought <strong>of</strong>," which is absurd.<br />

Thus if "a being greater than which cannot be thought <strong>of</strong>" can even be<br />

thought <strong>of</strong>, it is false to say that it does not exist; and it is even more false if<br />

such can be understood and exist in <strong>the</strong> understanding.<br />

www.<strong>for</strong>dham/edu/halsall/source/anselm.htm<br />

But…<br />

You cannot use this argument to prove that anything exists. Perfection<br />

does not extend into <strong>the</strong> contingent world. <strong>Anselm</strong> covered this in his<br />

discussion <strong>of</strong> Gaunilo’s objection to <strong>the</strong> first part <strong>of</strong> his argument.<br />

So:<br />

1. <strong>God</strong> is <strong>the</strong> thought than which nothing greater can be thought.<br />

2. <strong>God</strong> is not a part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> contingent world.<br />

3. <strong>God</strong> is absolute perfection.<br />

4. <strong>God</strong> necessarily exists.<br />

Norman Malcolm (1911 – 1990) also suggested a way to understand <strong>the</strong><br />

concept <strong>of</strong> necessary existence. While he is not on your course<br />

specifications, it may help you to understand <strong>the</strong> concept <strong>of</strong> necessary<br />

existence if you read his argument!<br />

4