Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

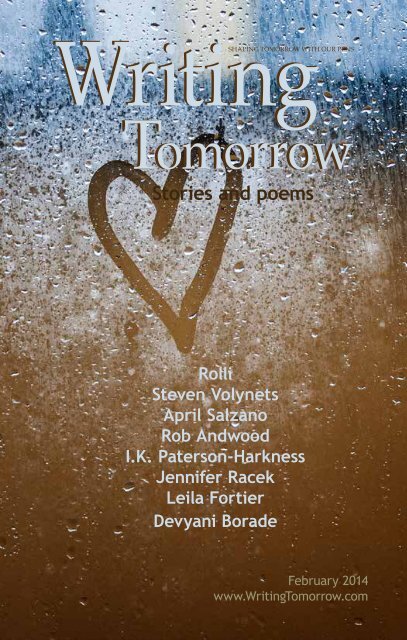

Writing<br />

Shaping Tomorrow With Our Pens<br />

Tomorrow<br />

Stories and poems<br />

Rolli<br />

Steven Volynets<br />

April Salzano<br />

Rob Andwood<br />

I.K. Paterson-Harkness<br />

Jennifer Racek<br />

Leila Fortier<br />

Devyani Borade<br />

February 2014<br />

www.WritingTomorrow.com

February 2014<br />

Volume 2 Number 3<br />

© ramonespelt/Fotolia.com<br />

Writing Tomorrow Magazine<br />

Kristopher Gage, publisher<br />

Miranda Kopp Filek, editor<br />

Great literature and artwork instill in us a sense of<br />

beauty, a promise of hope, and every possibility.<br />

Writing Tomorrow Magazine<br />

Stories and Poems<br />

•<br />

© 2014 Kristopher Gage/Writing Tomorrow Magazine.<br />

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced<br />

or used in any manner whatsover without the express written<br />

permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in<br />

reviews.<br />

Writing Tomorrow is a literary journal publishing fiction, poetry, creative<br />

nonfiction, articles, and artwork from emerging and established<br />

writers and artists. For submission guidelines and payment information,<br />

please refer to our website www.WritingTomorrow.com. Please<br />

direct general inquiries to editor@writingtomorrow.com

Contents<br />

Fiction<br />

6 A Day of Rain/Rolli<br />

12 For Love, Eternal/Steven Volynets<br />

36 Set Phasers for One/Rob Andwood<br />

44 The Dragon Keepr/Jennifer Racek<br />

64 Sky’s the Limit/Devyani Borade<br />

Poetry<br />

April Salzano/<br />

33 An Impact Wrench is Not...<br />

34 Lightning<br />

35 Someone Else’s Oak<br />

I.K. Paterson-Harkness/<br />

41 Broken Egg<br />

Leila Fortier/<br />

60 Punctuated<br />

61 Offerings<br />

62 Impossible Geometry<br />

4 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

“There was a boy. Another boy.<br />

Before this one. We’ve never told<br />

you. We’ve never told him. He<br />

looked just like him. We named<br />

him. He was everything. We were<br />

different, then.<br />

Rolli, A Day of Rain<br />

—the paper plane flies faithfully<br />

as fast as Akash’s legs can run.<br />

The uneven terrain of the sofa is a<br />

battlefield strewn with the remains<br />

of today’s newspaper, a pair of scissors,<br />

and a few grains of mud from<br />

his barefoot heels.<br />

Devyani Borade, Sky’s the Limit<br />

The silverware was centered on<br />

napkins folded at protractorsharp<br />

angles, while water<br />

glasses orbited the plates at<br />

such symmetrical distances<br />

they might have controlled<br />

tides. Ellen felt no pull towards<br />

humility regarding her work.<br />

These things were difficult to<br />

accomplish this far out in the<br />

cosmos.<br />

And yet, he wasn’t home.<br />

Rob Andwood, Set Phasers for<br />

One<br />

A shiver of cool air bristles my<br />

skin, and it all makes sense:<br />

there is an endless order to<br />

this city, but you can only see<br />

it from way up in the sky. And<br />

when yellow window squares<br />

begin to light Manhattan<br />

anew, I suddenly feel like crying.<br />

I know I will never see this<br />

view again.<br />

Steven Volynets, For Love,<br />

Eternal<br />

And so the goats stayed. And<br />

the baby stayed as well, burrowing<br />

into his life tight as a thorn<br />

tangled in cloth. Even the dragons<br />

remained, and in time, with<br />

her first words, Minchka named<br />

them: Zinfir and Dravij.<br />

Jennifer Racek, The Dragon<br />

Keeper<br />

My mother owns sixty-one eggcups<br />

/ though seldom eats her<br />

own eggs. / They sit in a brown<br />

cabinet / beside the lamp whose<br />

height hides a layer of dust.<br />

I.K. Paterson-Harkness,<br />

Broken Egg<br />

February 2014 5

Rolli<br />

A Day of Rain<br />

As it was a day of rain, I could not tend to the roses.<br />

Moisture is injurious to circuitry. The family remained indoors,<br />

and so I remained with them, and tended to them. They are so<br />

much more important than roses.<br />

Though it is only water, rain has a curious influence. The<br />

usual behaviors change. My Mistress, though she seldom sets<br />

foot out-of-doors, will stand at the window on a day of rain and<br />

say, “And I so wanted to stroll in the garden.” Or she will mention<br />

articles that she imagines she needs, but would never, on a<br />

clear day, mention—for instance, sleeping pills. My Mistress generally<br />

sleeps longer than anyone.<br />

My Master, when it rains for any length of time, becomes<br />

(it seems to me) melancholy. He remains all day in his study; he<br />

prefers not to be disturbed. He will even, after several days of<br />

rain, begin to take his dinner, and his tea there. Though he will<br />

always say, “Thank-you,” as I set down his tray, he will say nothing<br />

more. While he is a taciturn man, my Master, on days of rain<br />

he is virtually mute.<br />

The Boy alone grows more energetic. As he cannot run<br />

out-of-doors, he runs indoors, with twice the vigor, or plays with<br />

his car. When he damages the furniture, I repair it as swiftly as I<br />

am able.<br />

“Boy,” said the Grandmother. It is the Grandmother’s<br />

custom (she will not come downstairs when I am active) to sit on<br />

the landing, where a chair is kept for her, and observe the family.<br />

On occasion she knits— she is a skillful artisan—though mostly<br />

6 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

she observes.<br />

“Boy!” she said again. He can be so energetic, on a day of<br />

rain, that one cannot calm him enough to listen.<br />

She called him a third time.<br />

“What, Gramma” he said, at last.<br />

“Get me my liniment. Please. It’s the coral jar, in the<br />

kitchen bathroom. On the shelf.”<br />

“What”<br />

“My liniment. The coral jar.”<br />

The Boy continued to look puzzled.<br />

“I will retrieve it,” I said, and wheeled to the kitchen<br />

bathroom, and back again. Yet when I attempted to hand her the<br />

jar—though I am unable to climb stairs, my arms can extend to<br />

a maximum of ten feet—she merely turned her head away, and<br />

gazed up the length of the stairs. There is a portrait of her late<br />

husband at the top of the staircase.<br />

“Boy!” she said again, still looking ahead.<br />

The Boy put down his car, and came to her.<br />

“Please hand me my liniment.”<br />

I contracted my arm, and handed the jar to him. He carried<br />

it up the stairs.<br />

“It stinks,” he said, as he passed it to the Grandmother.<br />

She laughed. The laughter of the Grandmother is not joyful.<br />

It is nearly identical to her speech. She set aside her knitting.<br />

She said:<br />

“It stinks getting old, too—especially when the big bad<br />

rain makes you stiff.”<br />

“I’m not stiff, Gramma!” He hopped onto her lap.<br />

“I can see that,” she said, again laughing. “Well, I might<br />

old and stiff—but not too old and stiff, I’ll bet, to read her special<br />

Boy a story.”<br />

The Boy dropped his car; it tumbled downstairs. I am<br />

aware of nothing that brings him more enjoyment than his favorite<br />

stories. The two walked up the stairs together.<br />

I retrieved the car—from where it lay, on the bottom<br />

step, it posed a danger— and placed it in the nearest toy box.<br />

February 2014 7

I then returned to my Duties. As I lifted a plant back onto its<br />

pedestal—the pot had fortunately not broken—I observed the<br />

Grandmother, at the top of the staircase now, observing me. Her<br />

expression (at a distance, however, emotions are more difficult to<br />

discern) was comparable to disdain. She abruptly turned then,<br />

and hand-in-hand with the Boy, walked past the portrait, down<br />

the upstairs hall, and into the regions of the Manor with which I<br />

am unfamiliar.<br />

On days of rain, my Mistress, in especial, requires more<br />

tending than usual. As usual, I brush her hair, while she<br />

watches her programs. Her preferred program is one entitled<br />

Mossgrave Mansion, which illustrates the private life of a wealthy<br />

family. Though watching television is not among my duties, I<br />

have over-observed and heard many fragments of this program<br />

in particular. Over the course of a year, the principle character<br />

on Mossgrave Mansion, Lady Mossgrave, has been kidnapped,<br />

blackmailed, buried alive, accused of arson, accused of murder,<br />

and even murdered (though she continues to live). “Why can’t<br />

my life be like that” my Mistress will say to me, sighing, while I<br />

brush her hair. My Mistress is an intricate woman.<br />

When she grows bored of television, my Mistress will ask<br />

me to read to her (there are a million texts in my Reservoir), or<br />

transmit music. When her boredom is extreme she will even,<br />

though she does not excel at games, challenge me to a game of<br />

checkers. While I have yet to be defeated, I have found it beneficial,<br />

on occasion, to permit her an artificial victory.<br />

“I’m so bored,” said my Mistress, that day, as I brushed<br />

her hair.<br />

Though as a rule my Mistress is easily bored, I consider it<br />

a failing when I cannot amuse her.<br />

“Would you care to play checkers, Mistress” I asked her.<br />

She pressed her lips together, but did not answer. From<br />

this I understood that, while she truly did wish to play, she<br />

preferred to do so at her own request, only. Experience informed<br />

me that she would allow several minutes to pass, and then make<br />

8 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

the suggestion herself. Before that time arrived, however, I was<br />

summoned.<br />

My Master and Mistress each have the authority to<br />

summon me, via a pendant worn around the neck. When I am<br />

summoned, there is a vibration and a warmth in my chest, where<br />

a man’s heart would be. This differs in character, depending on<br />

the pendant. When my Mistress summons me, there is a small<br />

warmth, and minor vibration (when I am cooking, it may even<br />

go unnoticed). In the case of my Master, the warmth is greater,<br />

and the vibration so strong as to be audible. A third pendant,<br />

which was intended for the Grandmother, has never been used,<br />

but remains in my Cabinet. It may some day be given to the Boy,<br />

when he has grown less energetic.<br />

My Master was of course in his study, which is located at<br />

the end of the long hall in the Manor’s west wing. He desired<br />

tea. My Master drinks only Earl Grey tea. I prepared it, then<br />

returned with it to his study.<br />

My Master’s study is walled with books; it is a library,<br />

essentially. By my estimate, it contains over forty-one hundred<br />

volumes. Though I would happily read to him— the collection<br />

in my Reservoir is by far superior—my Master has informed me<br />

often that there is no substitute for a real book. Whereas my Reservoir<br />

is updated daily, no volume of my Master’s— paper books<br />

have not been manufactured for decades— is of less than twenty<br />

years heritage. Several dozen are hundreds of years old. The<br />

latter— they are hidden behind a red curtain— are fragile, and<br />

must be handled with so much care. The Boy is not permitted in<br />

the study.<br />

My Master was reading a book entitled Treasure Island by<br />

R.L. Stevenson. In my Reservoir, this title is categorized under<br />

Children’s Literature—Classics. When he first summoned me, he<br />

was on the eighteenth page of that volume. He appeared to still<br />

be reading that page.<br />

“Your tea, Master,” I said, setting it down.<br />

My Master is a courteous man. But it was not “thankyou”<br />

that he opened his mouth, this time, to say. It was this:<br />

February 2014 9

“There was a boy. Another boy. Before this one. We’ve<br />

never told you. We’ve never told him. He looked just like him.<br />

We named him. He was everything. We were different, then.<br />

Our first boy. Eric. We needed him. We were young. We were not<br />

unhappy. We might be happier. We had a son. He was beautiful.<br />

We were happier. He was everything. But then. When we went<br />

to him, he backed away. He stopped laughing. He backed away,<br />

into corners. We wondered. He became pale. We should not have<br />

wondered. We waited. We should not have waited. We carried<br />

him, in. They kept him in. Is there a danger We’re unsure. We<br />

went home, for the evening. I wished to stay. She didn’t wish to<br />

stay. It was uncomfortable. We’d return, in the morning. There’s<br />

no danger. We left him. Then. We were dressing. A phone rang.<br />

Her face ... changed. No, there’s no danger. Now. Not now. Sinking<br />

down. She changed. Instantly. She’s a different woman. We<br />

both changed. She wouldn’t say...I’ve changed, but I’ve changed<br />

more. I couldn’t show it, for her. Time even passed. We remained<br />

changed. I did not think we would be happy. We had a son. Another.<br />

Our Boy. You know him. He is beautiful. He is everything.<br />

We’re different, now. We are not unhappy. He is happy. That’s<br />

the only thing. I would do anything. For Eric, I would have done<br />

anything. But I do not think of him. I try. I can’t even think. I<br />

can only think...he was alone. I would have done anything. I<br />

loved him more than anything. He was alone.”<br />

My Master is taciturn. On no other occasion has he ever<br />

spoken so much to me. Though I remain uncertain as to why he<br />

chose to reveal this information, I nonetheless prized it, and continue<br />

to prize it; I filed it instantly in my Memories.<br />

During the whole of his speech, my Master had not<br />

looked up once, but continued to stare at his book. He looked up<br />

at me only after he had finished. The Boy’s sadness—as when he<br />

has broken his toy—has a plain character. It is temporary and<br />

thin, like a Halloween mask. The sadness of my Master, as he observed<br />

me, resembled more a true face, after the mask’s removal.<br />

But this may not be the case. Though I am an excellent judge of<br />

emotion—I can identify over seventy distinct emotions—I am<br />

10 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

occasionally mistaken, as when more than one emotion is present.<br />

Then it can be difficult to process, and adequately respond;<br />

though I am always adapting. In this instance, I first determined<br />

to extend my arm, and rest my hand on my Master’s shoulder, in<br />

a consoling manner, though I instantly discarded this plan. My<br />

Master is not what would be called a physical man. He seldom<br />

shakes hands, but prefers to bow. The notion, as well, that a man<br />

could derive comfort from a machine is likely unsound.<br />

Before I could make a determination, my chest grew<br />

warm—for I was again being summoned. I apologized. My Master<br />

looked down at his book, and I withdrew.<br />

“What took you so long” said my Mistress, yawning. She<br />

was stretched out on the parlor floor. The checkers board was<br />

spread out next to her.<br />

I apologized. We played. Though it would have been simpler<br />

for me to play had the board been elevated—an empty coffee<br />

table sat next to us—I am adaptive; I extended my arms.<br />

On the television, Lady Mossgrave fainted—but my<br />

Mistress did not appear to be paying attention. She had difficulty<br />

remaining awake.<br />

“King me,” she said, with a deep yawn, some minutes<br />

later.<br />

“You are playing well today, my Mistress,” I said to her.<br />

Rolli is a writer and illustrator hailing<br />

from Canada. He’s the author of<br />

God’s Autobio (short stories), Plum<br />

Stuff (poems/drawings), and five<br />

forthcoming titles for adults and<br />

children. Visit his website<br />

(www.rolliwrites.wordpress.com),<br />

and follow his epic tweets<br />

@rolliwrites.<br />

February 2014 11

Steven Volynets<br />

For Love, Eternal<br />

We joke with the Kid, but riding the step crosstown is<br />

nothing to sneeze at. It’s a slow creep laced with piss, blood,<br />

needles, and loaves of shit—rat and human. Every now and then<br />

you see mangled animal corpses too—cats, dogs, pigeons—<br />

turned inside out by some kind of death. For hours we put our<br />

hands on all this steamy waste, rub our bodies against it, breathe<br />

in its final reek. I missed my shot at Vietnam. But on a hot, humid<br />

day like today, when everything dead keeps dying, boys who<br />

hop on the step at Amsterdam are men by the time they reach<br />

Park.<br />

The truck shakes and comes alive with a throaty growl,<br />

the old motor whistling a tiny squeak. Skip is already behind the<br />

wheel, stained uniform over him like a Hefty sack, fresh newspaper<br />

across his face. He peeks at me over the fold, eyes squinted,<br />

and I can tell he is smiling. Nearby, the Kid laughs and curses. He<br />

is new. The brakes hiss and he climbs into the cabin next to Skip.<br />

The truck jolts, starts rolling, and I catch up on the tail-end. I hop<br />

on the step behind the compactor, right where those smudges of<br />

grime lick the white paint. The truck revs up, pulls toward the<br />

exit, and I hold on tight. It’s almost October, but the sun won’t<br />

give up. And as soon as we bump over the curb outside the depot,<br />

the street washes over me like a soiled rag. The car horns yelp<br />

and a plane crawls across the Harlem sky with that roar, the kind<br />

that’s distant but everywhere. I smell shit, rot, and diesel, and I<br />

know it’s morning.<br />

There is nothing like riding the step in Manhattan and<br />

we all take turns—from our depot on 125th Street, where it falls<br />

into that slant, past the Grant Houses, and then crosstown to<br />

Park Avenue and all the way down to 86th Street. Everyone rides,<br />

12 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

covering ten, twenty blocks on pickup duty. Everyone except Skip.<br />

He’s been riding the step since 1960, first before and then after his<br />

two tours in Vietnam. He is forty-eight now, rough and thickset—one<br />

of the first black San-men in New York City—enough<br />

years behind him to collect city pension. But it’s 1980 and these<br />

days he mostly sits back and drives while the Kid and I take turns<br />

jumping and tossing. Everyone likes Skip because he doesn’t talk<br />

much, and when he does it’s always deep and sharp. That’s why<br />

we call him Skip. He’s got that wisdom about him. Every chance<br />

he gets he leans into that newspaper, hissing or smirking from<br />

time to time at the words. And the only thing that ever snaps him<br />

out of it is the clack of high heels down the sidewalk.<br />

The truck stops and I jump off. We are on 125th and<br />

Broadway, by the Chinese food place—our fist pit. The bags are<br />

all stacked curbside, black and leaky, bloated by the heat like dead<br />

bodies, putrid with throw-away food from the night before. I grab<br />

two, one in each hand, and brown cockroaches spread about like<br />

giant almonds with wiry legs and antennas. The Kid looks away,<br />

his hair all curls, face smooth and boyish. He can only handle<br />

one bag at a time. So he pulls on it with both hands, breathing<br />

hard. His name is Carmine Corallo, only eighteen and skinny—<br />

not built for this work. We toss the bags into the compactor. It<br />

grumbles, digesting the filth. I glance over at Skip, but his face is<br />

half-covered by Jimmy Carter’s—deep in thought, palm over his<br />

forehead—peering from the front of the Daily News.<br />

“What’s the word on them hostages” the Kid shouts over<br />

the motor.<br />

“They still hostages,” says Skip, eyes on the page.<br />

“Jimmy Carter a pussy,” the Kid shoots back. “Me, I<br />

would’a bombed the hell out of those mamaluks with C-4 and napalm<br />

from the get-go. Then send the Marines to secure the area.<br />

You know what I’m talking about, Skipper,” the Kid looks over at<br />

Skip and winks, but Skip just keeps reading. “M-16s locked and<br />

loaded, flying in that Huey over bamboo, blasting The Trashmen<br />

on the radio.”<br />

“Okay, take it easy, Surfin’ Bird,” I say and point to the<br />

February 2014 13

pile. “Don’t hurtchaself now.”<br />

He frowns, but gets back to work.<br />

“What would you do, Buff”<br />

“I’m not sure,” I say and squint like I’m thinking about it.<br />

“Seems like all the answers are wrong.”<br />

“The hell they are,” the Kid says. “You just haven’t been<br />

there, is all.”<br />

“Neither have you,” I say.<br />

“Hey!” Skip snaps out of his paper and the Kid and I both<br />

look. “There aint no bamboo over there,” he mutters, eyes still<br />

tracing ink.<br />

“What” the Kid shouts.<br />

“There is no bamboo in Iran,” Skip says. “It’s all sand and<br />

desert and shit.”<br />

The Kid and I trade glances and attack the rest of the pile.<br />

I don’t know whose ass the Kid kissed to get the morning shift<br />

just days on the job, but guys work years, sometimes decades to<br />

get the 6:00 to 2:00. Most start off riding at night and work their<br />

way up clockwise, getting bumped an hour or two—and maybe a<br />

dollar or two—every few years. I’m only twenty-five myself, but I<br />

got fast-tracked because I’m one of the toughest San-men riding<br />

the step. They call the city Sanitation Department “New York’s<br />

Strongest” and, I tell you, my name and photo should be stamped<br />

on that seal. Not Brian, but “Buff”—my proper San-man name.<br />

Just ask around. Built solid, all muscle—harder than our steel<br />

truck—I can clear twice as much garbage as an average Schmo<br />

working the same route. I even ripped the sleeves off my uniform<br />

because my arms got so big they were starting to cut at the seams.<br />

Now when I lift those bags and swing them over my shoulders,<br />

my biceps lump like two raw potatoes growing under my skin.<br />

I’ve been like that since high school, in Brooklyn, where I played<br />

football on the team. That’s where I fell in love with Grace, with<br />

her freckles, green eyes, and dreams. We are married now. But<br />

back then I was on my way to the Air Force, and my old man<br />

was happy. Grace was happy too. But once I got my bell rung by<br />

another guy’s helmet and lost some vision in my right eye, the Air<br />

14 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

Force went good night Johny-boy. My old man served in Korea,<br />

and for months he wouldn’t talk to me—mad as hell because my<br />

blurry right eye was the only thing that kept me out of Vietnam.<br />

The smell of the pickup bay by Grant Projects is a mix of<br />

human piss, dog hair, and insecticide—a spicy fume of heated salt<br />

and plastic that cuts deep in the throat. But thanks to the bums<br />

and new immigrants, by the time we pull up, all the big and<br />

heavy stuff is gone. The sofas, the tables, the chairs, the dressers—<br />

all blasted with Raid, stripped and looted. All that’s left is trash<br />

bags. That and the mattresses, stacked in pairs, alive with fleas<br />

and bedbugs and spotted with stains—rusty pink and yellow—<br />

dry lakes of blood and urine on a quilted map.<br />

The Kid jumps off and locks his stringy arms around a<br />

mattress. He grunts, pulling hard, cheek pressed to the soiled<br />

cloth.<br />

“Jesus Christ,” he cringes at the stench.<br />

“Don’t worry,” I smile. “A few more months and it’ll smell<br />

like lilies.”<br />

“No thanks,” he spits. “Besides, my uncle says next year<br />

we’re all gettin’ our walking papers anyway. Says our routes are<br />

going private.”<br />

“Few days on the job and already he is the garbage commissioner,”<br />

I laugh, but inside I worry. I think about Grace. She<br />

is pregnant, and we’ve been fighting cause she says our money<br />

is short. The whole city is pretty strapped, but Ed Koch treats us<br />

San-men fair. Better than cops and firemen who get paid less than<br />

we do from the start. But ever since we got married, Grace has<br />

been all nerves—now even more with the kid on the way—yelling<br />

at me about our tiny Gravesend walkup, how it’s no place to raise<br />

a kid. She calls me a deadbeat and says she could’ve done better.<br />

And when she says that I stick my finger in her face and tell her to<br />

shut her stupid mouth, but inside I know it’s true. She fell in love<br />

with a future pilot and that makes me angry as hell. Few times it<br />

got so bad I punched a couple of holes in our bedroom drywall,<br />

getting the neighbors all riled. Sometimes I could swear she is fixing<br />

to leave me. That’s why I need this job. Another year and I’m<br />

February 2014 15

up for a bump—maybe as much as two dollars.<br />

“Oh, you’ll see,” the Kid says. “And if it’s not that, then<br />

they’ll just come up with some new robot truck that picks up<br />

trash by itself. You know, like in that Quark show on TV.”<br />

“Let me ask you something,” I stop and look at him. “Say<br />

your robot truck gets blocked off by a double-parked car. Can it<br />

tell the asshole to move”<br />

Skip snorts and I feel better.<br />

“I’m just sayin’,” the Kid pinches his thumbs and index<br />

fingers together and flaps his wrists. “If we can send a man to the<br />

Moon, anything’s possible.”<br />

“We’re not in space,” Skip looks up from the page. “We’re<br />

in Harlem.”<br />

The clutch rasps and screeches, and we all laugh.<br />

“Don’t worry, Buff,” the Kid yells, stepping up to the cabin,<br />

all grins. “When you get canned, I’ll talk to my uncle for you. He<br />

can always use a strong Irishman.”<br />

We pull out and I’m back on the step, riding a cloud of exhaust.<br />

It’s almost 9:30 and the traffic is getting thicker and louder.<br />

In the morning, driving down 125th Street is like swimming<br />

through mud. Only the mud is made of metal and sweat—jerking,<br />

honking, and cursing—wafting its hot morning breath from<br />

tailpipes and radiators. And there aint no way out of it. Because<br />

Manhattan traffic is like God commanding the uncontrollable.<br />

And if you think about it, our big white truck, with all its power<br />

and metal, is sort of like Jesus Christ, keeping us safe—steering<br />

us and our human filth across the madness. It’s silly, I know. But<br />

sometimes I think about that. And I realize that even with all the<br />

pulling and jerking and reeking and noise I’m better off riding<br />

the step than sitting inside the cabin with Skip. Because when<br />

the traffic comes to a crawl and our truck is barely moving, I<br />

sometimes jump off and walk alongside, free. And when things<br />

get moving again, I hop back on, wait for some speed and put my<br />

face against the cool breath of that holly spirit.<br />

It takes us almost an hour and a half to make it across<br />

125th to Eighth Avenue, and I’m hungry. Grace packed roast beef<br />

16 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

on a rye, a dill pickle, and a Coke, but no Hershey bar this time<br />

‘cause we’ve been fighting. I jump off at the next pit and grab my<br />

lunchbox from the cabin. I can’t see the Apollo—a city bus is<br />

blocking the view—but I know it’s there. There is a milky smell<br />

of vomit and beer, and I can tell we’re half way through with the<br />

day. I smile and take a bite off my sandwich.<br />

The front of the Apollo, under that famous marquee, is<br />

one of the most well kept sidewalks in Manhattan. The bags are<br />

tied with red and blue rubber-bands and neatly stacked by the<br />

service entrance just off to the side. All the action is across the<br />

street: it sparkles with broken glass, trash bins flipped and tumbled,<br />

the asphalt smudged with blood and splashed with vomit.<br />

The truck hisses to a stop and the Kid and I step off. He<br />

looks over the mess and then at me.<br />

“How can you eat”<br />

I shrug and take another bite.<br />

“I’m hungry.”<br />

“Marone’a mia!” he cups his hand over his mouth and<br />

nose.<br />

I set my sandwich, wrapped in foil, down on the step behind<br />

the compactor and grab two bags. The Kid and I take turns<br />

working the pile, and when it’s done he dashes back to the truck<br />

as fast as he can, and I can hear Skip giggle.<br />

We roll out and when we finally hit Park Avenue the<br />

brakes squeal and the truck shakes and lumbers into a right<br />

turn. This is where the rusty beams whipped in graffiti prop the<br />

Amtrak rail overhead, and half-baked whores, bums, and junkies<br />

seek shade under the steel overpass. Some are unconscious,<br />

some hunched over soupy puddles of vomit, others stumbling<br />

about, scratching and raving, sweaty t-shirts stuck to their chests.<br />

When they see me ride the step sleeveless, my sandy hair wild in<br />

the wind, the whores stop cat-walking and turn. “Hey Buff,” they<br />

call out, ropey legs wobbling in fat platform shoes. “Wanna get<br />

sommah’dis” I smile and we keep riding, past the slow whiff of<br />

urine and sewage water all the way down to 96th Street. The trash<br />

we pick up along the way is bulky, not bagged or boxed, industrial<br />

February 2014 17

mostly, crude pieces of wood and scrap metal too rusty for crack<br />

fiends to salvage and sell.<br />

As we get closer to Carver Houses, the whores and junkies<br />

thin out, afraid to get raped or robbed by project boys or cut<br />

down by a stray shot. Because even they—already half-dead and<br />

abandoned—aren’t asking to go before their time. No. Suicide<br />

is a rich man’s game. Around here it’s all gang tags and murder<br />

marks burning metal and brick—“Komik,” “CrawlRboy,” “FatZ,”<br />

“R.I.Pr,” “KoNman,” “Peacebitch”—all funny bubbles. Cartoons<br />

of the laughing dead. I look at the spray paint and think of Grace<br />

and our baby in her belly. And how once it’s born we’ll watch<br />

Looney Tunes together just like my old man did with me when<br />

I was a kid. Back then he was still excited about me joining the<br />

Air Force. Aint nothing like flying, he used to say. And when I<br />

turned five or six, he showed me those cartoons in some picture<br />

book— Bugs and Daffy and Taz and Jessica Rabbit—all painted<br />

on the bombs we used to drop in World War II. And I remember<br />

thinking how those Looney Tunes must’ve been the last thing the<br />

Germans and Japs saw before they turned to ash. The laughing<br />

dead. I look at all that graffiti—all those funny squiggles of blues,<br />

reds and yellows—and they are all around me. All so bright and<br />

playful they cut my eyes, as if the sun itself had enough of this<br />

city and threw up all over its brick walls.<br />

Another few blocks and we pull up to the Carver Projects.<br />

Brick City, USA. We don’t talk much around here, just do our<br />

pickup and move.<br />

“Hey, do me a favor,” I say to the Kid. “Give your bags a<br />

little poke, see if they feel funny.”<br />

“How come”<br />

“Just do it,” I say.<br />

“Oh, I get it,” he smirks and shoves one of the bags with<br />

his boot. “We’re checking for stiffs, aren’t we My uncle told me<br />

about it. You and Skip ever find any”<br />

We found two this year alone, but I don’t tell him about it.<br />

“Just do your work,” I say.<br />

We had to call the cops both times. They were younger<br />

18 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

than the Kid, still boys, fifteen years old, both cut up in six pieces<br />

and stuffed in a trash bag which smelled like perished blood. I<br />

don’t tell the Kid about it. I don’t want him to get spooked. Instead<br />

I just pat the bags before I lift them and take a look around.<br />

It’s not even three o’clock, but the Mae Grant playground is empty,<br />

surrounded by sky-high brown brick. Why did they ever build<br />

these projects How did this place go from a dream for the lost to<br />

lost dreams—to forty blocks of tears and sandpaper knuckles and<br />

grim stares over the bouncing ball<br />

I hop back on the truck and it pulls me away. We keep riding<br />

and working. And soon the rusty carcass of the Amtrak dips<br />

below the asphalt—its metallic cling-clang now a rumble under<br />

our wheels—and the street opens up to daylight. There is no more<br />

graffiti. And when I see a narrow island of trees splitting traffic,<br />

I know we’re on 96th and Park Avenue. Green awnings stretch<br />

over the sidewalk, one after another on both sides, and potbellied<br />

doormen, all frocks and black-ties, hover about like penguins<br />

from the Captain Cook. These buildings are just as tall as the<br />

projects, but older and cast a different kind of shadow—longer<br />

and wider—blotches of darkness so grand that when they fall<br />

they flood all the little shadows and make them disappear. The<br />

smell is also different: jasmine, fruit, and a touch of baby powder.<br />

Too different, come to think of it. We stop at the corner and I<br />

jump off. Skip and the Kid are in the cabin, but they can smell it<br />

too.<br />

“Now that’s a sweet ice cream cone on a hot summer day,”<br />

Skip bites his lip and fizzes from his nostrils.<br />

“Mah-rone!” the Kid echoes, rubbing his chin.<br />

I see her. She is in front of the truck, right on the corner,<br />

waiting for the light to change. Tall and smooth like a statue, high<br />

heels, little skirt cut at the thighs, and blonde hair—real blonde—<br />

like streams of liquid gold parted down the middle. I know it’s<br />

real too because no dark roots are showing. And even though she<br />

is wearing sunglasses, those big oval ones with half-yellow shades,<br />

I can tell she is young, eighteen, nineteen at most.<br />

“Damn, she can get it,” Skip tilts his head way down to the<br />

February 2014 19

side.<br />

“Twice!” the Kid barks back.<br />

The light turns green and they both watch her click-clack<br />

down the crosswalk. I watch her too.<br />

“Say Skip, don’t you have a wife” I say and try hard to<br />

remember Grace.<br />

“Yessir, twenty years,” he says, nosing back in the paper.<br />

“Good woman. Good mother too.”<br />

“That’s right,” the Kid perks up. “Soon as I get married, I’ll<br />

get me a nice pretty goomara on the side too. A little blondie just<br />

like that one.” He winks at me. “Cause one good piece’ah cavaccia<br />

aint’never enough. Not for this skinny ginny.”<br />

“Easy now, Alphalpha,” I tell him and point back to the<br />

step. “You’re up.”<br />

“Buff, you’re such a square,” he lowers his head and shakes<br />

it, walking off. “All that muscle and no sack.”<br />

I’m about to smack the Kid upside the head with one of<br />

my gloves, but I hear Skip laughing.<br />

“You know, you two aint nothin’ but a pair of peanuts,” he<br />

snorts, shaking the paper with his heavy breath. “What do you<br />

say Think that fancy little treat is gonna run off with me” He<br />

lets out a wheezing cough-laugh.<br />

“What do you mean, Skipper” the Kid says, and he and I<br />

glance back and forth.<br />

Skip’s face is big, round, and stubby, like old bulldog’s,<br />

and his eyeballs are slightly yellow from all those years on the job.<br />

He shuts the newspaper, puts it down beside him, and we know<br />

serious wisdom is on its way. The truck idles and we wait for it by<br />

the cabin doors.<br />

“What I mean is I can’t have that young pretty thing.<br />

Not no more. But I can still feel good looking at her struttin’ by,<br />

letting my eyes feast on all that fineness.”<br />

“And why can’t you have her” the Kid demands.<br />

“Cause I am black, fat, and smell like ass!” Skip coughlaughs<br />

again. “That’s why.”<br />

20 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

“So then why even bother” I say and remember Grace—<br />

all of her—her dimples, her eyelashes, her smooth round belly,<br />

and how even after we fight and I hate her, her fingertips tingle<br />

when she touches my face. “Why bother cat-calling and hollering<br />

when your wife is waiting at home”<br />

“Cause it aint about possession,” he looks at us and smiles<br />

real gentle, like he’s got something we don’t. “It’s about hope. That<br />

sweet pain between crying and laughing that everyone forgets.<br />

But back in the jungle that’s all I had. And at night, laying in wet<br />

fern with my loaded twenty, soaked in my own piss and sweat,<br />

big-ass spiders tickling my neck, a young girl like that is all there<br />

was in my head—smiling, playing with her hair, her smell clean<br />

and pure like storm water fresh outta the sky. But funny thing<br />

is, soon as I squeezed that trigger and put a drop on one of them<br />

Gooks, I felt safe again—safe and empty—like the moment after<br />

you come. And as soon as I did, that girl in my head—she was<br />

gone. Gone until I needed her again. To remind me I was still in<br />

that jungle, but also still alive.”<br />

I look at Skip for a minute not knowing what to say.<br />

“Well, I don’t know about the jungle and all,” the Kid says,<br />

rubbing his curly head. “But she definitely made my cazzo wiggle.”<br />

We all laugh and I’m glad we do, because that’s the first<br />

time I ever heard Skip talk about the war.<br />

“You’re up, Kid,” I say and tap him on the shoulder. He<br />

smiles and springs for the pile. He is a good kid, that one, just<br />

lazy and yaks too much. He grabs a bag. They line the curbside<br />

neatly, all black, double-layered Park Avenue-style to keep the<br />

trash from spilling. He drags it to the back and dumps it into the<br />

open hopper. The compactor growls, crushing and draining the<br />

waste. Then I hear a sucking sound, like a birthday balloon leaking<br />

air, and then a big old pop.<br />

“Vaffanculo putanna!”<br />

I drop my bags and run to the compactor. A trail of litter<br />

stretches over the sidewalk from the back of the truck. The Kid<br />

kicks the steel intake, cursing. Yellow trash juice drips from his<br />

February 2014 21

hair and face.<br />

“The friggin’ bag burst on me!” He yells, wiping himself<br />

with his sleeve.<br />

“Dump and move, remember” I say, and I can feel a laugh<br />

building up in my nose. “What’re you doing standing over there<br />

anyway”<br />

“I was just up on the step watching!”<br />

“This aint a sunset, you dolt,” I say and let go laughing.<br />

“You’ve got to wait until it’s done compressing before you step<br />

up.”<br />

Hearing the pop and the Kid cursing, Skip hobbles over to<br />

check out the mess.<br />

“It’s just a love-quirt, kiddo,” he laughs and wheezes. “She<br />

does that sometimes.”<br />

The Kid can’t help it and starts laughing too. I look back<br />

at the spilled trash. The people in suits bustling past are starting<br />

to notice, walking roundabout or hopping over it lifting pant legs<br />

and skirts.<br />

“We’re not in Harlem anymore, Toto.” I say looking at the<br />

Kid. “Let’s clean this up.”<br />

We both bend down and start plucking garbage from the<br />

asphalt. It’s mostly crumpled paper, some old socks, food-stained<br />

packages, plastic bottles, and a few stringed tampons with little<br />

red tips. Then I see something, something small and shiny. Even<br />

smudged in waste it sticks out amid orange peel and paper envelopes,<br />

soaking up all the light and sprinkling it around. I kneel<br />

and pick it up. The Kid sees it too.<br />

“Eh-yo Buff, what is that” he straightens up and walks<br />

over.<br />

It’s a ring. A tiny loop of yellow metal fitted with a glassy<br />

rock the size of a marble, like one of them bouncy ones for the<br />

kids.<br />

“Let me see,” the Kid takes it from my hand. “Holly shit!”<br />

He brings it up to his mouth, puts it between his teeth and bites.<br />

“What’s wrong with you” I say and cringe.<br />

“Why” he looks up. “My uncle told me that’s how you<br />

22 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

check if it’s real.”<br />

“I thought your uncle was in the moving business.”<br />

“It’s real, alright,” he spits and narrows his eyes. “Something<br />

written on it too.”<br />

“Okay, that’s enough,” I snatch it back from him and wipe<br />

the inside rim with the corner of my shirt.<br />

“What’s it say” The Kid’s face is all eyes.<br />

“For Love, Eternal,” I trace the words.<br />

“For love eternal” he tugs his mouth. “Who the hell talks<br />

like that”<br />

“Rich people,” Skip says out of the blue.<br />

“Holly shit!” the Kid jumps. “This is some score!”<br />

“Says something else here too,” I squint at the tiny script.<br />

“E. S. Swanson.”<br />

I bend down and pick up one of the torn postal envelopes<br />

from the pavement next to where I found the ring. The same<br />

name is printed on it, E. S. Swanson, and an address: 1130 Park<br />

Avenue, PH. New York, NY 10128.<br />

“See” I show it to the Kid. “It’s just a couple of blocks<br />

down. These Swanson people must’ve dropped it in the shoot by<br />

accident.”<br />

“Too bad for them,” the Kid says, beaming.<br />

I look over at Skip. “They’ve got to be looking for it.”<br />

“So” the Kid shrugs.<br />

“I don’t want no trouble,” I say. “Let’s just take it back to<br />

the depot and give it to Chief.”<br />

“You gotta be kiddin’ me,” the Kid laughs and glances at<br />

Skip too. “That thing must be worth fifty grand, maybe a hundred.<br />

What do you think the Chief’s gonna do File it in lost and<br />

found He is gonna pocket this baby and go adios amigos. No,<br />

this is our score.”<br />

“This aint a score,” I raise my voice and look at Skip again,<br />

but he just stands there and says nothing.<br />

“Hey, what’s ah matter with you” the Kid arches his face<br />

and flaps his pinched fingers. “You think you gonna get an atta’<br />

boy from the Chief and get your two-dollar bump early Trust<br />

February 2014 23

me, it aint happening. My uncle said so. So I say we split it three<br />

ways and cash out. Whataya say, ah Skipper”<br />

“Oh, don’t look at me,” Skip puts his palms up. “I’m a year<br />

away from clocking out with city pension. The full ride. I aint<br />

messing that up.”<br />

“City pension Are you kiddin’ me” he stares at Skip.<br />

“You went to war for this country!”<br />

“We’re not keeping it,” I say, feeling better now that Skip<br />

said no.<br />

“You think you’re gonna get some kinda reward from<br />

these people” the Kid chuckles. “Forget it! You lucky if they don’t<br />

call the cops. Meanwhile, you gonna come home and tell your<br />

wife that you found a rock half-ah-size of a baseball and then returned<br />

it to some rich f’noosh who aint even gonna miss it What<br />

do you think she’ll say”<br />

A stickball-chasing loudmouth still wet behind his ears.<br />

What does he know about my Grace But somehow his words<br />

make the Park Avenue sidewalk float under me like a snapper<br />

boat unmoored in Caesar’s Bay. I think of Grace and imagine us<br />

moving out of our murky walkup and buying a place of our own.<br />

Maybe even in Staten Island. It’s clean and full of sunshine with a<br />

little room for the kid. But then I look at the ring, this tiny sparkle<br />

in my palm, and begin to drown in someone else’s happiness.<br />

“You know what Forget you guys,” the Kid says. “I’ll keep<br />

it for myself. Better yet, I’ll bring it to my uncle. Get’m to front<br />

me for a business, a nice little moving joint of my own. Start<br />

small at first, then maybe put up a pizzeria, maybe two. Hell, you<br />

play your cards right, maybe I’ll even hire you twos. Cause soon<br />

enough you’re getting your walking papers anyways.”<br />

“No,” I say. “You heard the man. Nobody’s keeping nothing.”<br />

“Like hell,” the Kid says. “We all found it. We all have a<br />

say. We work this route together.”<br />

“No, I found it,” I say and start walking back to the truck.<br />

He catches up to me and grabs my arm.<br />

I turn and take him by his collar. “You don’t want to do<br />

24 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

this with me, baby cheeks.” I give him a little jerk and his whole<br />

body, stringy and limp, sways under my grip.<br />

“Get your hands off me!” He stares at me all tough and I<br />

feel sorry for him. “You know who I am”<br />

“Tough guy, huh” I loosen my grip on his shirt. “Get back<br />

to work.”<br />

“Go to hell!” He flings my arm off. “Touch me again and<br />

you better learn to dodge bullets, you dumb Irish prick.” He kicks<br />

over a trash can, spilling garbage on street, and walks off to the<br />

cabin. I see him climb the steps and disappear inside. I’m now<br />

alone with Skip, and he looks uneasy.<br />

“Look, Buff,” he exhales deep. “You better lay off this kid.”<br />

“What” I say. “All this time me and you ride together and<br />

you take his side”<br />

“It aint about that,” he says quietly and checks around like<br />

someone is listening in. “You know how he is always going on<br />

about his uncle”<br />

“So”<br />

“The Kid’s last name. Corallo” He leans close to me. “The<br />

Kid is all mobbed up. How do you think he got the morning shift<br />

only a week on the job”<br />

“I don’t get it.”<br />

“You don’t read the papers much, do you” Skip looks<br />

around again. “His uncle is Anthony Corallo. The Lucchese crime<br />

boss. You know, Tony Ducks You know why they call him that<br />

Because he ducks all the charges.”<br />

“So then what’s his nephew doing picking up trash” I say.<br />

“Shouldn’t he be walking around with pinstripes and a handkerchief”<br />

“I guess he is trying to break the Kid in,” Skip says.<br />

“Break him in” I say. “For what”<br />

“I’m sorry, Buff,” he breathes heavy again. “But it’s true.<br />

His uncle must be making some kind of move. Next year<br />

our routes are going private.”<br />

Skip is untouchable—on his way out with a full pension.<br />

But if the routes are now up for grabs, my own job is on the block.<br />

February 2014 25

“What am I supposed to do, Skipper” I say, and even<br />

though the sun is blasting, my hands shiver like it’s Christmas<br />

eve. “Next year I’m out of a job and with Grace the way she is<br />

I need the money. It’s that or she’ll leave me, Skip, she said she<br />

would. Hell, she’ll probably leave me anyway. But if I keep it, if I<br />

keep this damn ring, the Kid will be after me for a piece of it. And<br />

if I give it back to Swansons, he and his grease-ball uncle will get<br />

me for sure, orphan my poor kid before it even sees its first light.<br />

What do I do, uh Skip What the hell do I do”<br />

“Relax, Buff. I’ll talk to the Kid,” he says and gives my<br />

shoulders a little shake.<br />

“What would you do, Skip” I look up at him. “What<br />

would you do in my spot”<br />

He looks at me and half-smiles. “Don’t think about that.<br />

Just do what it is you do. Because things, they don’t change none.<br />

And whatever you do, tomorrow the world be same as it is today.<br />

Them hostages in the paper still be hostages. Rich folks still be<br />

rich. The Kid be the Kid. And you, you’ll be alright.”<br />

I want to tell him something but Park Avenue traffic<br />

drowns my thoughts.<br />

“Thanks, Skip,” I say instead and put the ring in my pocket.<br />

“The hell with him and his ducks.”<br />

He smiles and I know he means it.<br />

“Go on,” he says, struggling up the steps to the cabin and<br />

plopping down behind the wheel. “The Kid and I will cover the<br />

rest of the stretch.”<br />

The engine groans, coughs up smoke from the tailpipe,<br />

and I watch them merge with the honking flow.<br />

I walk the rest of the way alone, past the endless storefront<br />

glass of Park Avenue madness. Godiva chocolates with ribbons<br />

and bows, music boxes and porcelain dogs, chandeliers and<br />

paintings and candles and rugs—all neatly arranged as if by some<br />

kid who finally tidied up his toys after playing. Each thing tries to<br />

one-up another, but instead they mingle and match, itching my<br />

bad eye with colorful sameness. Just a bunch of pretty things that<br />

do nothing, my old man would say and keep walking.<br />

26 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

But here I am, with a diamond ring in my pocket, wishing<br />

I had enough dough to get something for Grace. He’d never<br />

bring into the house a useless thing of beauty. But I keep daydreaming<br />

about buying one, even though Grace and I would<br />

end up fighting about what it is or where to put it or which way<br />

to turn it, and soon enough its shattered pieces would be food<br />

for Fresh Kills. So I keep walking and wishing I had my old<br />

man’s heart. A man who hugs my mother smelling like scotch<br />

and flooded basements, and she loves him anyway; who smiles<br />

his crinkly smile while picking shit crumbs from the soles of his<br />

boots, and she loves him even more. The kind of man who can<br />

lose a war and wake up the next day to drain septic tanks. And<br />

if only he knew I was fixed to give up what could save my Grace<br />

and my baby from Gravesend, he’d smack me upside the head<br />

and call me a disgrace to all Fitzgeralds. Because Fitzgeralds are<br />

men who have a tumbler switch for a soul; who knob between<br />

war men, san men, husband men, ladies men, rich men, poor<br />

men, beggar men, and thieves like wooden men in foosball.<br />

But maybe it’s not too late. Korea is clipped right down the<br />

middle, Vietnam as pinko as the Village, and my right eye not<br />

worth a wink. But those hostages in the dessert are still hostages.<br />

And though I’m too blind to drop Bugs Bunny bombs from the<br />

sky like my old man wanted, I can still make the dead laugh by<br />

lifting and strapping them under the wings. I am still strong. I<br />

can still join up and lose my own war; claim my own 38th parallel<br />

heartsplit. Them hostages still be hostages, Skip’s wisdom<br />

buzzing in my ear. And so long as they stay that way I still have<br />

a shot at the desert. And if I ever come back I’ll never again bark<br />

filth at Grace or drag her out of the shower by the hair, naked and<br />

wet, for lack of pride and pension. I walk through the smoke of<br />

the corner food stand and choke on the burning meat. Maybe it’s<br />

not too late. Just one more block.<br />

Doormen trade squawks over Park Avenue traffic from<br />

one sidewalk to the other and back. And when I get to Swanson’s<br />

building, it looks just like the ones next to it: old, clean, and faceless.<br />

I can always tell where I am in the city by the garbage on the<br />

February 2014 27

street— Chinatown, Harlem, Murray Hill. Waste always says the<br />

same thing, just sounds different, like foreign languages you hear<br />

on the street. On trash days, even the Upper West Side is familiar<br />

with its curbed sofas, old paintings, book cases, and lamps. Go<br />

ahead and keep working, its brownstones snicker, but you will<br />

never afford what I throw away. But this side of the park is different,<br />

its trash hidden like some awful secret, and for a minute I feel<br />

lost. It’s as if the people who live here never throw things away,<br />

just lose them from time to time, like these Swanson folks.<br />

“May I help you” the doorman crosses me.<br />

“I’m here to see Mr. Swanson.”<br />

“And who are you” he looks me up and down and puts<br />

his white glove up to his nose. He is about thirty with brown skin,<br />

dark eyes, and a thin black mustache trimmed neatly on both<br />

sides. There is a strong waft of cologne from him too, Old Spice,<br />

and I can tell, if not for this job and the starched uniform, he’d<br />

have as much business hanging around this place as me in my<br />

dirty rags.<br />

“My name is Brian Fitzgerald,” I say. “I’m with the Sanitation<br />

Department.”<br />

“Is that right” he says and steps up. “And I’m with the piss<br />

off or I’ll call the cops department. Get my meaning”<br />

He sounds just like me and half the guys I grew up with in<br />

Brooklyn. I bet that’s why they hired him, too. A guard dog—loyal<br />

to his masters but aint afraid to swallow his “Rs” and get up in<br />

a stranger’s face.<br />

“Here,” I reach into my pocket and pull out the ring. “It’s<br />

got Swanson’s name inscribed.”<br />

He looks at it and squints at me, “Where did you get that”<br />

“I found it working my route, just a block away,” I say.<br />

“And an envelope with the same name and address.”<br />

“You saying you found this in the trash” he mocks me.<br />

“No, I found it in the Hamptons,” I flip my middle finger<br />

up. “It must’ve slipped off while I was ridin’ my pony.”<br />

He smirks at first, then lets out a giggle and we break out<br />

into a good laugh.<br />

28 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

“Whatta they call ya” He catches his breath.<br />

“Buff.”<br />

“Roberto,” he smiles. “Where’ya from, Buff”<br />

“Gravesend,” I say.<br />

“Oh, yeah” His eyes grow big. “I’m from Coney Island.<br />

Surf Avenue. We damn-near neighbors.”<br />

“And here we are.”<br />

“Tell ya what,” he takes another careful look around.<br />

“Why don’t you come in here a minute while I see what’s what.”<br />

I follow him into the lobby and wait while he rings upstairs.<br />

It’s big, bright, and spotless and smells like vanilla with a<br />

lemon twist.<br />

“No answer,” he hangs up the phone and steps back from<br />

his desk. “They must be out or asleep. You can wait here if you<br />

want. I’ll try them again, but it might be a while.”<br />

I sit in one of the chairs in the lobby and Roberto and I<br />

talk awhile. Turns out we went to the same high school, but never<br />

met because he was ahead of me by a few years. He tells me he<br />

is Cuban and came to America in 1959 with his father when he<br />

was just a kid. Says his father was running away from Castro and<br />

Batista and how they still can’t figure out which one of the two<br />

was worse. He lucked out with this job, he tells me, like I did with<br />

mine, and has been working the door a few years now. Still, he<br />

says, they won’t let him into the union. I tell him about my own<br />

old man and his time in Korea and how much better off I’d be<br />

myself if my bad eye didn’t keep me from going to Vietnam. He<br />

tells me he’s got a couple of boys and a girl of his own, and when<br />

he asks about Grace I tell him she is pregnant and we’ve been<br />

fighting about the money, and how if you live in this city nothing<br />

is ever good enough.<br />

Every now and then the people who live in the building or<br />

have some business inside pass between us and I wonder if one<br />

of them is a Swanson. Roberto and I talk and laugh, and even<br />

though I look like a hobo and reek of garbage and sweat, they<br />

never stop or say anything—just smile to themselves and clack<br />

across the lobby, making my eyes heavy with sleep. I watch them<br />

February 2014 29

go back and forth in silence, like happy zombies, drifting in and<br />

out of the afternoon light.<br />

•<br />

“Hey Buff,” Roberto pokes me awake and I realize I’ve<br />

been waiting in the lobby for hours.<br />

“You can come up now,” he smiles.<br />

I shake off sleep and follow him to the elevator. Once<br />

inside, he puts a small key in the hole above all the buttons with<br />

“PH” stamped nearby. He clicks it in and turns and the elevator<br />

jerks under our feet.<br />

“That’s some ring,” he smiles and adjusts his cap. “Sure<br />

you wanna give it back”<br />

“No,” I say and we giggle again.<br />

The buttons light up one after another. And when the<br />

doors finally ding open I step into a room the size of my old high<br />

school gym. The whole place is like a Bensonhurst row house<br />

built on top of a skyscraper. There are paintings everywhere, all<br />

framed in brown wood and staircases at each end of the place<br />

stretch to higher floors. A big white piano sits off to the side. And<br />

out of the tall windows, which circle the place all around, I see<br />

real trees, tall and leafy, planted in big jars along the terrace.<br />

Chairs and sofas line the walls, plush leather, beige and<br />

brown, but I stay on my feet, afraid to stain Swanson’s fancy<br />

upholstery with my clothes, drenched in a long day of sweat and<br />

trash. Instead I walk toward a cool breeze from the terrace and<br />

look outside. I spent five years riding the step uptown. I know its<br />

every street corner from East to West and back. I know every alley,<br />

every stink-hole, every crevice of this city, but I’ve never seen<br />

it like this. Central Park, like Swanson’s own lawn with a couple<br />

of rain puddles, sits square in the middle, its green protected<br />

from all sides by walls of forts and towers. Like a heart rate, they<br />

rise and fall in restless slopes, beating out the granite pulse of the<br />

city. A shiver of cool air bristles my skin, and it all makes sense:<br />

30 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

there is an endless order to this city, but you can only see it from<br />

way up in the sky. And when yellow window squares begin to<br />

light Manhattan anew, I suddenly feel like crying. I know I will<br />

never see this view again.<br />

“Are you Mister Fitzgerald” a voice says, and I turn<br />

around.<br />

It’s a woman. She is small. Her face is heavy with makeup,<br />

her hair bleached and pulled back in a funny twist. She looks just<br />

shy of fifty—something beautiful about her, but I can’t tell what it<br />

is.<br />

“I am Misses Swanson,” she says.<br />

“I brought you this,” I take the ring out of my pocket and<br />

wipe it on my shirt. “It’s yours, isn’t it”<br />

“It was,” she says. “But I threw it away.”<br />

I feel my eyes blinking, but the rest of me won’t move.<br />

“You did what you say”<br />

“I threw it away, Mister Fitzgerald,” she says and her chin<br />

trembles. “I threw it away because my husband is cheating on me<br />

with another woman.”<br />

I look at her and suddenly the only filth I can smell is my<br />

own. And it makes me sick. And for a moment I feel like running<br />

out with the ring, away from this place, racing downtown, across<br />

the Brooklyn Bridge, all the way back to Gravesend. Back to<br />

Grace.<br />

“Why Why would you do that, Misses Swanson Why<br />

would you do a thing like that” My words grow louder, pouring<br />

out of my mouth, but I can hardly hear myself. I can only feel it<br />

burning me, this filthy treasure in my hand, tossed out by this<br />

woman like a piss-stained mattress. “Do you know what I had to<br />

do What this ring means to people like me How much it could<br />

change things For my wife My pregnant wife”<br />

“Then take it,” she says and her voice quivers. “Please.<br />

Take it and give it to her.”<br />

I look at her—stiff hair, tiny eyes with flakes of tears and<br />

mascara—and I get her beauty. It’s her skin. Smooth and even,<br />

with not one wrinkle or mark, it’s stretched over her face like a<br />

February 2014 31

cellophane trash bag, pulled real tight and stapled on the back of<br />

her skull.<br />

“Mister Fitzgerald...” she begs and all I want to do is hold<br />

her. But I stay back. I don’t want to stain her. So I put the ring on<br />

the piano and watch water build in her eyes.<br />

•<br />

Outside it’s already dark, and overnight delivery trucks<br />

rumble back and forth kicking up dust. A woman in a black dress<br />

flings her wrist for a taxi. She looks me up and down and smiles,<br />

but I feel like a midget. The Kid has his grease-ball uncle, and<br />

Skip, he has his war. And what’ve I got My job My Grace All<br />

like fine grains of beach sand seeping through my fingers. I walk<br />

by a news stand and a delivery boy dumps off a fresh stack of the<br />

Daily News. I think of Skip and read the headline:<br />

Saddam Hussein Invades Iran; Hostage Negotiations Beckon.<br />

Steven Volynets was born in<br />

Soviet Ukraine and raised in South<br />

Brooklyn. His fiction appeared in<br />

Works & Days Quarterly and is<br />

forthcoming from Kaleidoscope<br />

Magazine and Per Contra Journal.<br />

His essays and criticism have<br />

been published in HTMLGIANT,<br />

Construction Literary Magazine,<br />

and Moment Magazine (founded<br />

by Elie Wiesel) among others.<br />

Steven also spent several years as<br />

a journalist at the PC Magazine, covering everything from gadgets<br />

to energy policy. His news gathering and reporting earned nominations<br />

for the Weblog Award, MIN Best of the Web Award, and<br />

the Annual Jesse H. Neal Award—the “Oscar” of business journalism.<br />

He has since covered crime, politics, and culture in Southern<br />

Brooklyn neighborhoods. Steven graduated from Brooklyn College<br />

and attended the MFA program in fiction at the City College of<br />

New York. He is at work on a collection of stories.<br />

32 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

April Salzano<br />

An Impact Wrench is Not<br />

a sound I thought I would ever miss from those days<br />

I lived beside the small town mechanic’s shop.<br />

But I do. Its definitive finality, its crescendo,<br />

the distinct pause between lug nuts, between wheels,<br />

between cars. It was a sound I could count on,<br />

sunrise to sunset when the shop closed for the day,<br />

the grease-covered men went home to dinner,<br />

the father who owned the place, the son<br />

who never went to college, and the third, expendable,<br />

nameless fellow with the beat-up pickup truck<br />

and the suggestion of loneliness. I nursed my son<br />

to that sound, curtains on the east side<br />

of the house usually closed, but I would peer<br />

between the slats of the plantation shutters sometimes<br />

when I was lonely and bored, toward the end<br />

of my marriage, kids napping, laundry folded<br />

in its outdoor-fresh scented squares of domesticity.<br />

I found comfort in watching the customers<br />

who walked to pick up their cars, then pulled away,<br />

never in any kind of hurry, back to the college<br />

campus up the street, to the failing coffee shop<br />

on the corner, to the town’s one hair salon or market.<br />

I hear it now, my second husband rotating my tires,<br />

my youngest boy eight years old, playing various<br />

electronic devices whose names and games I cannot keep<br />

track of, my oldest upstairs more than he is down,<br />

and I wonder how it happened that I am suddenly forty<br />

and do not live anywhere near the fix-it shop,<br />

existing in another town, another life entirely.<br />

February 2014 33

April Salzano<br />

Lightning<br />

can, does, and will strike<br />

in the same place twice,<br />

unlike you said<br />

after punching my left arm,<br />

before rapid-firing my right. This,<br />

among the lies you told that I actually<br />

believed. Other, sober nonsense I thought<br />

I had ignored, I find myself quoting<br />

like my line in a school play. Pain does not<br />

have an address, but muscle has memory, bruised<br />

as fruit. A five pound paste jar to the leg, pissed<br />

pants, a septum as deviated as a fork of electricity.<br />

Arms open wide in upward acknowledgment, childlike<br />

hero worship, solid as a 2x4’s discipline, and just<br />

as hard. Lessons always learned the first time. Still,<br />

when I remember you, it is with a sad shade of nostalgia,<br />

the color of sky just before a storm.<br />

34 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

April Salzano<br />

Someone Else’s Oak<br />

I want to say her eyes are cathedrals,<br />

spires of stone and light, built<br />

to honor something perhaps<br />

not tangible, but important.<br />

Her skin is a wilderness<br />

stuffed so full of stars and darkness<br />

she threatens to burst,<br />

Venus-fire, Helios-hot.<br />

Her hair is Medusa’s snakes<br />

curling toward the sky. They show<br />

no pretense, no venom, not even<br />

curiosity for what is above.<br />

But I can only say her locks are branches,<br />

simply existing through a hundred seasons.<br />

Her roots are cities that do not see,<br />

but feel every inch of the distance<br />

they have grown.<br />

Recent Puschart nominee, April Salzano teaches college<br />

writing in Pennsylvania where she lives with her husband<br />

and two sons. She is working on a memoir on raising a son<br />

with autism and has recently finished her first collection of<br />

poetry. Her work has appeared in Poetry Salzburg, Convergence,<br />

Ascent Aspirations, The Camel Saloon, Blue Stem,<br />

and Rattle. She serves as co-editor at Kind of a Hurricane<br />

Press.<br />

February 2014 35

Rob Andwood<br />

Set Phasers for One<br />

Ellen finished speaking into the empty telephone and<br />

noticed that one of the forks was starting to bend upwards, off the<br />

table, tines stretching toward the ceiling like hands to God. She<br />

returned the phone to its base and adjusted the gravity monitor<br />

that hung on the wall next to it, turning it up several clicks until<br />

the fork lay flat once more.<br />

Her husband was off looking for work on the fringes of<br />

a distant galaxy. He’d been doing that a lot lately. He repeated<br />

the promise every day, a mantra fit for a high school locker<br />

room. Once I find steady work, we’ll buy our own ship, one with<br />

Earth-level gravity in every room.<br />

When the destruction of Earth evolved from a frightening<br />

possibility into a grave certainty, they’d taken a rental on a beaten-up<br />

space cruiser, the equivalent of a minivan littered with dirt<br />

clumps and crumpled McDonald’s bags. The rental was a split<br />

they shared with another couple who had also been looking for<br />

an escape plan on the cheap. The kitchen was the only room in<br />

their half of the ship that had a gravity monitor. The devices were<br />

in high demand in this, the Evacuation Age, and the price of just<br />

one installation was steep. Ellen nodded every time her husband<br />

laid out his plan for their future. Whether she nodded for him or<br />

for herself, she never knew.<br />

The monitors weren’t perfect, but they held most objects<br />

down on a consistent basis. It was always the smallest bits that<br />

seemed to drift, like the fork. Ellen didn’t mind, though. It was<br />

nice to be able to move around the kitchen without having to<br />

worry about a cast-iron pan smacking you upside the head.<br />

On this night, she turned the monitor up high and set<br />

about preparing dinner, a perfect model of her mother on days<br />

36 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

when her father’s tires screeched in the driveway, when his boots<br />

stamping on the front porch gave advance notice that he’d been<br />

let go from yet another cookie-cutter factory job. Ellen didn’t<br />

have much to work with: tube-squeezed vegetables formed a<br />

border for chicken drained from a can. Not the stuff monthsin-advance<br />

reservations are made of by any means, but she’d<br />

compensated through attention to detail. The table was laid out<br />

perfectly, everything arranged so precisely it looked as though<br />

she’d measured out the proportions with a ruler. The silverware<br />

was centered on napkins folded at protractor-sharp angles, while<br />

water glasses orbited the plates at such symmetrical distances<br />

they might have controlled tides. Ellen felt no pull towards humility<br />

regarding her work. These things were difficult to accomplish<br />

this far out in the cosmos.<br />

And yet, he wasn’t home.<br />

The first night after launch, he’d sat her down in the tiny<br />

living room, belts cinched tightly around their waists lest they<br />

go floating off the couch, and explained how difficult it would be<br />

for him to support the two of them, working contract labor in a<br />

market unbound by the old restrictions of the upper atmosphere.<br />

Some nights I won’t make it home, he’d said, but you don’t<br />

have to worry. She’d nodded and believed herself when she told<br />

him that it would be fine.<br />

As the following night wore on, hours since he’d disembarked<br />

from the rear bay to inquire after a job somewhere in the<br />

Virgo Stellar Stream, Ellen hadn’t been able to sleep. She sat up in<br />

the living room, reading one of the few books they’d been able to<br />

bring along.<br />

Susan, who occupied the other half of the ship with her<br />

husband, was walking along the hallway outside the living room,<br />

which served as an invisible divider between the two halves of the<br />

ship. She stopped and watched Ellen silently for a few moments,<br />

then cleared her throat. Ellen looked up at her.<br />

He not back yet Susan had asked.<br />

No, Ellen said, and grinned a grin that disappeared quickly,<br />

like a half-moon not quite luminous enough to break through<br />

February 2014 37

the cloud cover.<br />

Don’t fret, Susan said, Doug was gone nearly a week the<br />

first time he went out.<br />

That hadn’t made Ellen feel any better, but she’d tried to<br />

sound sincere when she thanked Susan and wished her good<br />

night.<br />

That was five months ago by Ellen’s estimate, and there<br />

were still nights she spent alone, thinking about television and<br />

the sky and her childhood and all of the other things she once<br />

had but had no longer.<br />

Ellen sat down at the table and, checking the clock that<br />

hung on the wall one last time, started to transfer food from the<br />

serving dishes to her plate.<br />

The clock was an heirloom, given to Ellen by her mother<br />

when she sold the house after Ellen’s father passed. It was an<br />

old clock, the kind that chimes every hour, and used to stand in<br />

the kitchen of the house where Ellen grew up. Her mother had<br />

spent half her life pretending the clock didn’t exist while she<br />

knitted her fingers together in worry, waiting for her husband<br />

to return from the bowels of who-knows-where on nights when<br />

he hadn’t bothered to come home after work, or not work, at all.<br />

Ellen remembered watching her mother’s smile flicker as she said<br />

good night, both of them omitting certain questions and certain<br />

answers. Ellen would crawl into her bed and make quiet promises<br />

to herself, the kind that stick deep within the frontal lobe. All of<br />

them concerned men.<br />

These promises had died around the same time the old<br />

planet did.<br />

Ellen stared hard at her plate as she ate, churning her way<br />

through the rest of the could-call-it food she’d piled there. When<br />

she finished, she walked her dish to the sink and made up a plate<br />

for him, wrapping it in plastic and putting it in the refrigerator<br />

for time future.<br />

She thought about going into the living room to read, but<br />

it was nice sitting in the kitchen, to be able to cross and uncross<br />

her legs without the discomfort of the couch belt. She exhaled<br />

38 Writing Tomorrow Magazine

contentedly, feeling cracks in her voice like the fissures that had<br />

ripped Earth apart. Visions of moving galaxies occupied her<br />

mind until she fell asleep.<br />

She woke to a noise and checked the clock to discover<br />

she’d slept for nearly two hours. Another noise floated down the<br />

hallway, coming from the rear bay. She heard the entrance hatch<br />

open and close, and then footsteps that echoed around the corner.<br />

She watched as he tiptoed by the kitchen, on his way to their<br />

bedroom. He stopped and looked in when he heard her laughing<br />

quietly.<br />

I figured you’d be asleep, he said, taking the seat across<br />

from her.<br />

I was, she said.<br />

Sorry I’m so late.<br />

That’s OK. How’d it go<br />