Chapter 16 - McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Chapter 16 - McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Chapter 16 - McGraw-Hill Ryerson

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

C h a p t e r Si x t e e n<br />

National Unity<br />

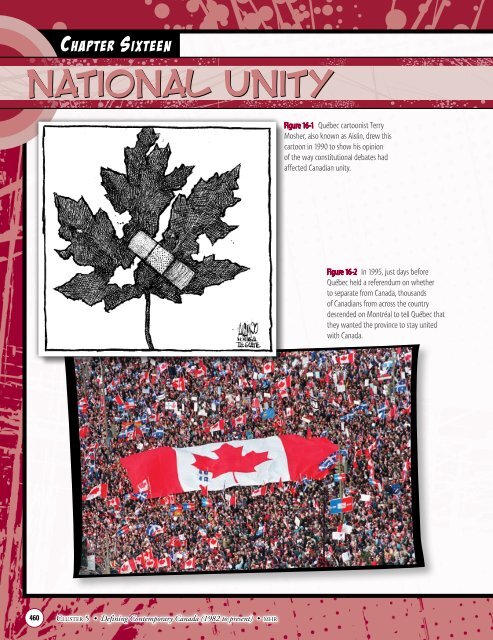

Figure <strong>16</strong>-1 Québec cartoonist Terry<br />

Mosher, also known as Aislin, drew this<br />

Figure 7-1 cartoon In 1970, in 1990 Manitoba show celebrated his opinion its 100th anniversary<br />

of entering of the into way Confederation. constitutional As debates part of had that celebration, in<br />

1971 a statue affected (below) Canadian of Métis unity. leader Louis Riel was unveiled<br />

on the grounds of the Manitoba Legislature in Winnipeg. In<br />

the following years, controversies erupted over the statue; over<br />

Riel’s naked and contorted figure, and over the role Riel played<br />

in the time leading up to Manitoba’s entrance into Confederation<br />

and beyond. In 1995, the statue was removed from the grounds<br />

of the legislature to Collège universitaire de Saint-Boniface<br />

and was replaced on the grounds of the legislature by another<br />

statue (left). The removal and replacement of the original statue<br />

caused a controversy of its own.<br />

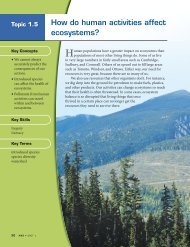

Figure <strong>16</strong>-2 In 1995, just days before<br />

Québec held a referendum on whether<br />

to separate from Canada, thousands<br />

of Canadians from across the country<br />

descended on Montréal to tell Québec that<br />

they wanted the province to stay united<br />

with Canada.<br />

image P7-39<br />

460 Cl u s t e r 5 • Defining Contemporary Canada (1982 to present) • m h r

How has the question of national unity influenced federalism,<br />

constitutional debate, and political change<br />

To explore this essential Essential question, Question, you will<br />

• examine the issues, attempts events, to have and Québec people sign that the shaped Canadian the history<br />

of Constitution the Métis in through Western the Canada Meech from Lake 1869–1885 Accord and including the<br />

- Charlottetown the sale of Rupert’s AccordLand<br />

• - investigate the Red River the debate Resistance over Québec’s place in the Canadian<br />

-<br />

federation<br />

the role and legacy of Louis Riel<br />

•<br />

-<br />

explore<br />

the Manitoba<br />

the formation<br />

Act, 1870<br />

of new federal political parties and their<br />

regional interests<br />

- the dispersal of the Métis<br />

• discover challenges in federal–provincial relations<br />

- the Northwest Resistance<br />

• examine the political, social, and economic lives of the Métis<br />

Getting Started<br />

before and after Confederation.<br />

When the British North America Act was patriated in 1982, the<br />

Government of Québec refused to give its assent—approval for<br />

Getting<br />

the act. Québec’s<br />

Started<br />

refusal kept alive the question of its place in<br />

Study Confederation. the two statues Should of Québec Métis leader be given Louis status Riel as on a page distinct 100. society How<br />

are This these question two statues opened similar the door How for are other they regions different to also The question controversy<br />

whether about the the statues Canadian is important government part understood of understanding or appreciated history. their It is<br />

about distinctiveness. understanding Discontent the past became to better so strong understand in the the West present. that some<br />

began To to understand talk about Riel, separation you must from Canada. National unity became<br />

look a growing deeply concern and widely for many into the Canadian citizens and for the federal<br />

past. government. What different perceptions<br />

and<br />

• Examine<br />

perspectives<br />

Figure<br />

about<br />

<strong>16</strong>-1<br />

Riel<br />

on page<br />

do<br />

460. What<br />

you<br />

does<br />

see<br />

this<br />

in these<br />

cartoon<br />

statues<br />

say about the toll that<br />

• Was national he a unity victim debates of colonialism had on Canada<br />

• Did How he, might like ordinary so many historical Canadians be<br />

leaders, affected take by debates charge about and help national to unity<br />

• shape Examine the Figure future <strong>16</strong>-2. of the What West does this rally<br />

• Was say about he a martyr Canadians’ for all desire for national<br />

Canadians unity Do you think the same would<br />

• Was happen he the if the founder West wanted and protector to separate from<br />

of Canada a sovereign Why Métis or why state not<br />

• Was he, as many during his time<br />

believed, a traitor to Canada<br />

• Was he all of these None of<br />

these Or is there truth, in part,<br />

to all of them<br />

Ke y Te r m s<br />

assimilated Meech Lake Accord<br />

Marginalization<br />

Charlottetown<br />

Mé Accord tis National<br />

Calgary Committee Declaration<br />

Michif Clarity Act<br />

reconciliation<br />

Romanow Report<br />

river lots<br />

scrip<br />

square-mile lots<br />

surveyors<br />

Enduring Understandings<br />

Enduring Understandings<br />

By the end of this chapter, you will gain a greater<br />

understanding that:<br />

• Nouvelle-France, Acadie, Québec, and<br />

• The relationship francophone between communities Aboriginal and across non-Aboriginal<br />

Canada<br />

peoples may have be broadly played a defined role shaping as a transition Canadian from<br />

pre-contact history through and the identity. stages of co-existence,<br />

colonialism, and cultural and political resurgence<br />

• As a result of Québec’s unique identity and<br />

• Since the beginnings history, its of place colonization, in the Canadian First Nations, confederation Inuit,<br />

and Métis peoples continues have to be struggled the subject to retain of debate. and later, to<br />

regain their cultural, political and economic rights<br />

• French–English relations play an ongoing<br />

• Nouvelle-France, role in the Acadie, debate Québec, about and majority–minority<br />

francophone<br />

communities responsibilities across Canada and have rights played of citizens a role in in Canada.<br />

shaping Canadian history and identity<br />

• The role of government and the division of<br />

• The history powers of governance and responsibilities in Canada is in characterized Canada’s federal by<br />

a transition system from indigenous are subjects self-government of ongoing negotiation. through<br />

French and British colonial rule to a self-governing<br />

confederation of provinces and territories<br />

m h r • National Unity • Ch a p t e r <strong>16</strong><br />

461

HS<br />

E<br />

C&C<br />

C C<br />

HP<br />

ED<br />

Thinking Historically<br />

Establishing historical significance<br />

Using primary-source evidence<br />

Identifying continuity and change<br />

CHECKFORWARD<br />

Analyzing cause and consequence<br />

Taking a historical perspective<br />

Considering the ethical dimensions<br />

of history<br />

CHECKBACK<br />

You learned about the growth<br />

of Québec nationalism and the<br />

FLQ in <strong>Chapter</strong> 14.<br />

Th e Pl a c e o f Qu e b e c in Ca n a d a<br />

‘<br />

The Rise of Québec Nationalism to 1980<br />

The Quiet Revolution marked the beginning of another rise in Québec<br />

nationalism. Growing pride in Québécois culture inspired a new sense<br />

of nationalism in Québec. Many Québécois believed that their culture<br />

and identity would be better protected if their province separated from<br />

Canada. In the 1960s and 1970s, there were violent reminders of this desire<br />

to separate, including the FLQ crisis. Beginning when René Lévesque<br />

founded the Parti Québécois in 1968, Québec nationalism took a new<br />

political goal. It become focused on achieving sovereignty for Québec. In<br />

1980, the first sovereignty-association referendum was held in Québec.<br />

Although sovereignty-association was defeated, the referendum showed that<br />

a large number of Québécois wanted to pursue the idea of independence.<br />

Recognition as a Distinct Society<br />

As you learned in <strong>Chapter</strong> 15, Québec did not sign the 1982<br />

Constitution Act because it felt excluded from the final deliberations.<br />

In spite of this, the Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that the<br />

Constitution applies to Québec whether it has signed the Constitution<br />

or not. Prime Minister Trudeau believed that patriating the<br />

Constitution would dampen the sovereignty movement in Québec.<br />

However, some Canadians believe that the patriation process increased<br />

the strength and determination of Québec séparatistes. Many Québécois,<br />

whether sovereigntists or federalists, sought the recognition of Québec<br />

as a distinct society. Among those who supported Québec sovereignty,<br />

the recognition of Québec as a distinct society was viewed as an<br />

essential first step toward separation from Canada.<br />

Changing Politics in Canada<br />

In 1984, Trudeau stepped down as leader of Canada’s<br />

Liberal Party and as prime minister. Trudeau was replaced<br />

by John Turner, who quickly called for a federal election,<br />

hoping to win another Liberal victory. But by then, the<br />

Liberal Party had been in power for most of the previous<br />

twenty years. The party faced a long list of complaints, and<br />

in the election, the Liberals were soundly defeated. The<br />

Progressive Conservative Party and its new leader, Brian<br />

Mulroney, came to power.<br />

Figure <strong>16</strong>-3 Brian Mulroney’s victory in the September 1984<br />

federal election marked a significant change in Canadian<br />

politics. After almost twenty years of Liberal governments,<br />

Canadians elected a Progressive Conservative majority<br />

government.<br />

462 Cl u s t e r 5 • Defining Contemporary Canada (1982 to present) • m h r

Meech Lake Accord<br />

A bilingual Québécois, Prime Minister Mulroney had strong support in<br />

his home province, especially among federalists. He viewed the failure to<br />

include Québec in the Constitution as a key political issue and promised<br />

to deal with Québécois dissatisfaction over the way former prime minister<br />

Pierre Trudeau had patriated the Constitution.<br />

Mulroney believed that the time was right to persuade the Québec<br />

government to sign the Constitution. René Lévesque had retired; the<br />

Parti Québécois had been defeated in the 1985 provincial election; and<br />

Québec’s new Liberal premier, Robert Bourassa, was a federalist.<br />

HS How might Québec’s acceptance of the Constitution have affected the<br />

lives of Canadians in general How would gaining Québec’s acceptance<br />

have been historically significant<br />

Bourassa’s Demands<br />

In response to Mulroney’s pressure on Québec<br />

to sign the Constitution Act, Premier Bourassa<br />

established five demands that he said would<br />

have to be included in any new constitutional<br />

arrangement so that Québec could sign with<br />

dignity and honour:<br />

• veto power for Québec on any<br />

constitutional amendments<br />

• input for the province on the naming of<br />

justices to the Supreme Court of Canada<br />

• limits on how the federal government spent<br />

funds in Québec<br />

• increased power for Québec on immigration<br />

• recognition of Québec as a distinct society<br />

Initial Agreement at Meech Lake<br />

Mulroney launched discussions to resolve the Constitution issue, and<br />

in April 1987, a first ministers’ conference brought Mulroney and the<br />

provincial premiers together at Meech Lake, Québec. Mulroney’s goal was<br />

to persuade the premiers to accept that Québec’s language and culture<br />

made it a distinct society. Much to the surprise of a country that had<br />

become used to constitutional stalemate, Mulroney and the ten premiers<br />

agreed to a package of amendments to the Constitution. In June 1987,<br />

they all signed the Meech Lake Accord in Ottawa. It appeared as if<br />

constitutional harmony was finally achieved.<br />

Figure <strong>16</strong>-4 Robert Bourassa celebrates<br />

a victory for the Liberal Party of<br />

Québec in the 1989 provincial election.<br />

Bourassa was premier of the province<br />

from 1970 to 1976 and then again from<br />

1985 to 1994.<br />

m h r • National Unity • Ch a p t e r <strong>16</strong><br />

463

Figure <strong>16</strong>-5 Gary Filmon was the<br />

premier of Manitoba from 1988 to 1999.<br />

Review Québec’s conditions for signing<br />

the Constitution on page 463. Why do<br />

you think Premier Filmon was initially<br />

opposed to the Meech Lake Accord<br />

CHECKFORWARD<br />

You will read more about<br />

Aboriginal peoples’ opposition<br />

to the Meech Lake Accord in<br />

<strong>Chapter</strong> 17.<br />

CHECKBACK<br />

Provincial Ratification Process<br />

Because the Meech Lake Accord would amend the Constitution, the<br />

premiers at the conference agreed that all ten provincial legislatures<br />

had to ratify—formally approve—the deal within three years of the<br />

first provincial approval. In June 1987, Québec’s National Assembly<br />

became the first province to ratify the accord, thereby setting a deadline<br />

of June 23, 1990, to gain the approval of all provinces.<br />

Although Québec accepted the accord almost immediately, other<br />

provinces faced a more difficult time. Manitoba, New Brunswick,<br />

and Newfoundland and Labrador had recently elected new provincial<br />

governments. The premiers of these provinces had reservations about the<br />

Meech Lake Accord. Under the leadership of Premier Howard Pawley,<br />

the Manitoba government had supported the accord in 1987. When Gary<br />

Filmon and the Progressive Conservative Party came to power in 1988,<br />

however, Filmon was initially opposed to the accord. Although Premier<br />

Filmon later supported the agreement, the Manitoba Legislature also had<br />

to agree to the terms of the Meech Lake Accord.<br />

In New Brunswick, Frank McKenna became premier in 1987 and at<br />

first opposed the accord, although he later accepted it. In Newfoundland<br />

and Labrador, the Meech Lake Accord was ratified in July 1988, but the<br />

new government under Premier Clyde Wells reversed its approval in April<br />

1990. However, Wells agreed to let the provincial legislature debate the<br />

accord. As the deadline of June 23, 1990, crept closer, and with the two<br />

provinces of Manitoba and Newfoundland and Labrador still needing to<br />

approve it, the Meech Lake Accord was in peril.<br />

Opposition to Meech<br />

At first, public opinion polls showed strong support for the Meech<br />

Lake Accord. As the deadline approached, however, this support<br />

decreased for many reasons, including the acceptance of Québec as a<br />

distinct society.<br />

Former Liberal prime minister Pierre Trudeau, a strong federalist,<br />

was one of the leading opponents of giving Québec distinct society status.<br />

He argued that labelling Québec a distinct society would encourage<br />

the séparatistes by making Québécois feel less a part of Canada. Other<br />

critics, especially women’s rights groups and labour unions, argued that<br />

the accord’s distinct society clause would allow Québec to override the<br />

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and deprive certain groups<br />

of their rights. Aboriginal organizations, such as the Assembly of First<br />

Nations, pointed out that, like Québec’s francophone society, First<br />

Nations, Métis, and Inuit cultures were also distinct. Aboriginal leaders<br />

were angry that they had not been consulted in the process, and protests<br />

against the accord took place across the country.<br />

Some people in western Canada opposed the Meech Lake Accord<br />

because they felt alienated from central Canada and resented the<br />

additional powers the accord granted to Québec. They argued that the<br />

agreement would make the provinces unequal.<br />

464 Cl u s t e r 5 • Defining Contemporary Canada (1982 to present) • m h r

The Failure of the Meech Lake Accord<br />

In April 1990, as president of the Métis National Council and Manitoba<br />

Metis Federation, W. Yvon Dumont spoke in favour of the accord in the<br />

Manitoba Legislature. The Métis organizations hoped the negotiations<br />

that would follow the accord’s acceptance would bring about the changes<br />

they wanted. However, other Aboriginal groups were not as supportive.<br />

On June 12, 1990, the Manitoba government’s last attempt to conduct a<br />

debate on the accord failed. The unanimous approval of the legislature<br />

was needed to allow further debate on the accord before the June 23<br />

deadline. With the support of the Assembly of First Nations, Elijah<br />

Harper, the only Aboriginal Member of the Legislative Assembly, voted<br />

against allowing the debate. His vote stopped the proceedings, and as a<br />

result, Manitoba could not approve the Meech Lake Accord. When this<br />

happened, Premier Clyde Wells withdrew his agreement to allow the<br />

Newfoundland and Labrador legislature more time to debate the accord.<br />

The Meech Lake Accord failed.<br />

Shortly after the failure of the accord, Premier Robert Bourassa<br />

delivered a speech to the National Assembly of Québec that captured his<br />

province’s frustration and that foreshadowed the growth of séparatiste<br />

feelings in the province. In closing his speech, Bourassa stated, “English<br />

Canada must clearly understand that, no matter what is said or done,<br />

Québec is, today and forever, a distinct society, that is free and able to<br />

assume the control of its destiny and development.”<br />

E Read the words of Elijah Harper in the Voices feature. What seemed<br />

to be his primary reason for opposing the Meech Lake Accord<br />

Bouchard and the Formation<br />

of the Bloc Qu b cois<br />

In Québec, many citizens were pleased the Meech Lake<br />

Accord had failed because they did not believe it gave<br />

Québec enough power. For many people in Québec, the<br />

failure of the accord was a signal that the rest of Canada<br />

was not willing to make sufficient compromises to keep<br />

Québec in the country. Bourassa said he believed that<br />

Québec was not understood by the rest of Canada.<br />

A group of federal politicians in Québec became<br />

so disillusioned at what they saw as English Canada’s<br />

rejection of their province that they broke away from<br />

their political parties. One of these politicians was Lucien<br />

Bouchard, who had been a cabinet minister under Prime<br />

Minister Brian Mulroney. Bouchard became leader of a new federal party<br />

called the Bloc Québécois. The Bloc was committed to the separation of<br />

Québec from Canada. The party argued that as long as Québec séparatistes<br />

paid federal taxes, they were entitled to representation in Ottawa. In the<br />

1993 federal election, the Bloc Québécois received 49 percent of the vote in<br />

Québec and obtained the second highest number of seats in the House of<br />

Commons. This meant that a party devoted to the separation of Québec<br />

from Canada assumed the status of the Official Opposition.<br />

Voices<br />

We need to let Canadians know that<br />

we have been shoved aside. We’re<br />

saying that Aboriginal issues should<br />

be put on the priority list.<br />

— Manitoba MLA Elijah Harper,<br />

June 12, 1990<br />

Figure <strong>16</strong>-6 With Lucien Bouchard as<br />

its leader, the Bloc Québécois formed in<br />

1991 after the failure of the Meech Lake<br />

Accord. The federal Bloc Québécois and<br />

the provincial Parti Québécois share the<br />

same political goal of independence for<br />

Québec.<br />

m h r • National Unity • Ch a p t e r <strong>16</strong><br />

465

P r o f i l e<br />

Elijah Harper<br />

On June 12, 1990, Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) Elijah Harper made national news and<br />

Canadian history when he voted against allowing the Manitoba Legislative Assembly to debate the<br />

Meech Lake Accord. His vote signalled not only the death of the accord, but also the determination<br />

of Canada’s Aboriginal peoples to fight for their rights and voice in the Canadian Constitution.<br />

Elijah Harper, an Anishini-Nimowin (Oji-Cree), was<br />

born on March 3, 1949, at Red Sucker Lake, a reserve<br />

in northern Manitoba. He attended residential<br />

schools in Norway House, Brandon, Birtle, Garden<br />

<strong>Hill</strong>, and Winnipeg. In 1971 and 1972, he studied at the<br />

University of Manitoba.<br />

Harper’s career in politics began early when, at the<br />

age of twenty-nine, he was elected chief of the Red<br />

Sucker Lake Indian Band, now known as Red Sucker<br />

Lake First Nation. His career in provincial politics<br />

started in 1981, when Harper became the first status<br />

Indian to be elected as an MLA for the Rupertsland<br />

constituency. He held this seat for eleven years and<br />

served in many positions as part of the Manitoba<br />

Legislative Assembly, including minister of northern<br />

affairs.<br />

As Prime Minister Brian Mulroney held talks and<br />

meetings about the proposed Meech Lake Accord<br />

in the late 1980s, Aboriginal Canadians became<br />

increasingly alarmed at their exclusion from the<br />

process and the absence of Aboriginal peoples’ rights<br />

from the negotiations. In opposing the debate over the<br />

Meech Lake Accord, Harper let Canadians know that<br />

Aboriginal rights must be included in any constitutional<br />

amendment.<br />

In 1992, Harper also opposed the Charlottetown<br />

Accord, even though it was supported by Ovide<br />

Mercredi, the national chief of the Assembly of First<br />

Nations. Harper resigned as MLA for Rupertsland<br />

in 1992, and in 1993, he was elected as a Member of<br />

Parliament for the Churchill constituency.<br />

Over the years, Harper’s strong advocacy for<br />

Aboriginal peoples’ rights and his humanitarian work<br />

has earned him many awards, including<br />

• Honourary Chief for Life, Red Sucker Lake First<br />

Nation<br />

• Stanley Knowles Humanitarian Award<br />

• 1990 Canadian Press Newsmaker of the Year in<br />

Canada<br />

• National Aboriginal Achievement Award, 1996<br />

• Order of the Sash (Manitoba Metis Federation)<br />

• Gold Eagle Award (for Outstanding Citizen from the<br />

Indigenous Women’s Collective, Manitoba)<br />

Today Elijah Harper continues to be an activist,<br />

promoting Aboriginal and human rights in Canada and<br />

around the world.<br />

Figure <strong>16</strong>-7 On May 20, 2008, Elijah Harper holds up the<br />

sacred eagle feather he held for spiritual strength during the<br />

Meech Lake Accord proceedings. Look back to page 3 in this<br />

book to see the 1990 photo of Harper with the feather.<br />

Ex p l o r a t i o n s<br />

1. How was Elijah Harper’s role in the Meech Lake<br />

C&C Accord a turning point in Canadian history<br />

2. Research one of the awards that Elijah Harper has<br />

received and write a short report on the reasons why<br />

he won the award.<br />

C C<br />

466 Cl u s t e r 5 • Defining Contemporary Canada (1982 to present) • m h r

Charlottetown Accord<br />

Despite the failure of the Meech Lake Accord, Prime Minister Mulroney<br />

remained determined to bring Québec into the Constitution, and he<br />

tried to learn from Meech’s failure. The Meech Lake Accord came to be<br />

known as the “Québec round” of negotiations. It had focused on meeting<br />

Québec’s needs. Part of the reason Meech Lake failed, however, was that<br />

it did not address the needs of some other provinces, Aboriginal peoples,<br />

women, and other groups.<br />

In 1991, Mulroney launched a new round<br />

of constitutional discussions that became<br />

known as the “Canada round” of negotiations.<br />

He held five national conferences to talk about<br />

constitutional issues. In 1992, the negotiations<br />

led to the Charlottetown Accord, which<br />

was named after the Prince Edward Island<br />

city where the agreement was reached. The<br />

Charlottetown agreement was similar to the<br />

Meech Lake Accord in that it recognized<br />

Québec as a distinct society and promised<br />

greater powers for the provinces. It also,<br />

however, recognized Aboriginal peoples’ right<br />

to self-government and proposed an elected<br />

Senate with an equal number of senators from<br />

each province and with seats reserved for<br />

Aboriginal peoples.<br />

Québec planned to hold a referendum<br />

on the Charlottetown Accord. In response, the Canadian government<br />

decided that all Canadians would vote on the Charlottetown proposal in a<br />

national referendum.<br />

All three major political parties supported the Charlottetown Accord,<br />

but in the last weeks before the referendum, there was a swell of public<br />

opinion against the agreement. Many chiefs in the Assembly of First<br />

Nations were suspicious of the promises in the accord, despite the fact that<br />

the national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, Ovide Mercredi, had<br />

helped draft the proposal. Other Canadians believed the accord gave too<br />

much power to Québec and not enough to their own provinces.<br />

On October 26, 1992, the Charlottetown Accord won approval in<br />

only four provinces: Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island,<br />

New Brunswick, and Ontario. Across Canada, the vote was 45.7 percent<br />

in favour, 54.3 percent opposed. Québec rejected the accord by a margin<br />

of 56.7 percent to 43.3. Once again, Canadians had been unable to agree<br />

on constitutional change.<br />

E Read the Voices feature on this page. What does it tell you about the<br />

role anti-Québec feeling in other provinces may have played in the failure<br />

of the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords Do you think, as Geddes<br />

does, that anti-Québec feelings were a major factor, or do you think other<br />

factors were more significant Explain your answer.<br />

Figure <strong>16</strong>-8 The final agreements for<br />

both Confederation in 1867 and the<br />

Charlottetown Accord in 1992 were<br />

reached in Charlottetown, Prince Edward<br />

Island. Cartoonist Adrian Raeside based<br />

his cartoon on this fact. What message<br />

do you think Raeside wanted to convey<br />

in this cartoon<br />

Voices<br />

There were, of course, legitimate<br />

grounds for opposing change that<br />

explicitly set Québec apart from the<br />

other provinces. But something less<br />

rational, and at times ugly, was also<br />

in play. Even today, the main players<br />

on both sides of the debate hesitate<br />

to discuss the degree to which<br />

outright anti-Québec bigotry was<br />

behind the fierce opposition to the<br />

[distinct society] clause.<br />

— John Geddes, Ottawa<br />

bureau chief, Maclean’s, 2000<br />

m h r • National Unity • Ch a p t e r <strong>16</strong><br />

467

establishing historical significance<br />

HS<br />

Twenty Years After Meech<br />

June 23, 2010, was the twentieth anniversary of the failure of the Meech Lake Accord.<br />

Newspapers across the country ran editorials that reflected on the Meech Lake Accord and<br />

Québec’s relationship with the rest of Canada over the past twenty years. Andrew Cohen,<br />

a native Montréaler, journalism professor, award-winning journalist, and author of A Deal<br />

Undone: The Making and Breaking of the Meech Lake Accord, wrote the article “We Survived<br />

the Death of Meech,” which appeared in the Globe and Mail on June 23, 2010. Here are<br />

selected excerpts from his article:<br />

Long before the end of the Meech Lake Accord on<br />

June 23, 1990, politicians were warning that Canada<br />

would not survive its death . . .. For three years, that<br />

was the lament from the Meech Lake architects: So<br />

critical was their exercise in nation-building that Canada<br />

could not long endure without it.<br />

Twenty years later, we know that wasn’t so. Canada is<br />

still here and Québec is still part of it . . .. That Canada<br />

endured . . . is one of the lessons of the Meech Lake<br />

Accord, the longest of the constitutional wars that<br />

seized Canada from the mid-1960s to the mid-1990s.<br />

There were other lessons.<br />

Meech Lake taught us that constitutions could<br />

no longer be made in secret. The accord, a set of<br />

constitutional amendments, was negotiated in private<br />

by the first ministers in a day-long session on April 30,<br />

1987, on the shores of Meech Lake in Québec. It was<br />

adopted 33 days later at an all-night session in Ottawa.<br />

At first, it was widely praised; there was hardly a<br />

politician anywhere who opposed it. But the more<br />

Canadians learned about Meech Lake, the more they<br />

distrusted it.<br />

Had they been consulted, as they were in the making of<br />

the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1980 and 1981,<br />

they might have claimed ownership. But they resented<br />

that Meech Lake was revolution from above; it was<br />

constitution-making by stealth and its collapse was a<br />

body blow to executive federalism . . ..<br />

Why the popular opposition to these seemingly<br />

moderate constitutional reforms While few Canadians<br />

cared about spending power, immigration or allowing<br />

the provinces a say in appointing high court judges and<br />

senators, they were suspicious of recognizing Québec<br />

as “a distinct society.” More generally, they worried<br />

about the devolution of powers [transfer of power from<br />

the federal government to the provincial governments].<br />

Today, we can ponder the consequences if Meech Lake<br />

had passed. Perhaps Québec would have lived happily<br />

ever after within Canada. No Bloc Québécois, no<br />

Charlottetown agreement . . ..<br />

More likely, though, the Parti Québécois would have<br />

used distinct society to claim significant powers for<br />

Québec in social policy. For sovereigntists, it was winwin<br />

either way. Had they succeeded, they would have<br />

moved Québec toward de facto [actual] sovereignty;<br />

had they failed, they would have said Meech Lake was<br />

a lie.<br />

Meech Lake began with good intentions. It went<br />

badly wrong, divided English and French, and plunged<br />

Canada into psychodrama that drove us to the edge<br />

of the abyss in the referendum in Québec in 1995. It<br />

showed us that it is almost impossible to change our<br />

constitution—and dangerous to try.<br />

But it also showed that the people were right, the<br />

political class was wrong and that our Canada takes a<br />

lot of killing.<br />

HS<br />

1. According to Andrew Cohen, how did people in 1990<br />

judge the significance of the failure of the Meech Lake<br />

Accord<br />

2. From Cohen’s perspective, twenty years after<br />

the failure of the accord, what was its historical<br />

significance<br />

468 Cl u s t e r 5 • Defining Contemporary Canada (1982 to present) • m h r

Québec Referendum on Sovereignty, 1995<br />

In response to the failure of the Meech and Charlottetown Accords,<br />

Québec citizens elected the Parti Québécois in 1994 and Jacques Parizeau<br />

became premier. Known for his support of separation, Parizeau promised<br />

Québécois that they would be able to vote in a sovereignty referendum on<br />

October 30, 1995.<br />

The question that the Québec government proposed for the<br />

referendum was<br />

Do you agree that Québec should become sovereign, after having made a<br />

formal offer to Canada for a new Economic and Political Partnership, within<br />

the scope of the Bill respecting the future of Québec and of the agreement<br />

signed on June 12, 1995<br />

The bill referred to in the question allowed for one year of<br />

negotiations with Canada before sovereignty was declared. The agreement<br />

that was mentioned in the question referred to a deal among the Parti<br />

Québécois, the Bloc Québécois, and the Action démocratique du Québec<br />

(a provincial political party) to support separation. The wording of the<br />

question was hotly debated. Many voters believed there were too many<br />

ways to interpret the question. Despite the issues over lack of clarity, the<br />

question remained the same.<br />

Even though only Québec residents could vote in the referendum,<br />

the importance of the event was felt across Canada. Many federalist<br />

Canadians found ways to tell Québécois they wanted them to remain a<br />

part of Canada. On October 28, more than 100 000 Canadians from<br />

many provinces came to Montréal to hold a unity rally.<br />

On October 30, 1995, 4 757 509 votes were cast in Québec: 50.58<br />

percent opposed separation and 49.42 percent supported it. Although the<br />

federalist side was successful, the vote was too close to clearly and finally<br />

resolve the sovereignty debate.<br />

In the years since the referendum,<br />

support for sovereignty in Québec has<br />

gone up and down. In May 2010, an<br />

opinion poll in Québec showed that<br />

58 percent of Québécois believed that<br />

the sovereignty debate was “outmoded,”<br />

while 26 percent believed it was “more<br />

relevant” than ever. Other opinion<br />

polls consistently show that if<br />

another referendum were held,<br />

roughly 40 percent of Québécois<br />

would vote for sovereignty.<br />

. . . Shaping Canada Today. . .<br />

The Canadian Press voted the 1995<br />

referendum Canadian Newsmaker of<br />

the Year. This marked the first time that<br />

an event, rather than a person or group,<br />

had been chosen for this award.<br />

Figure <strong>16</strong>-9 “Oui” supporters celebrated at the<br />

Palais des Congrès de Montréal as the referendum<br />

votes started to come in.<br />

m h r • National Unity • Ch a p t e r <strong>16</strong><br />

469

The Calgary Declaration, 1997<br />

In 1997, deep divisions existed in Canadian society and politics. The<br />

debates over constitutional change and the split vote in the Québec<br />

sovereignty referendum made this clear. Although the differences between<br />

Québec and the federal government attracted the most attention, there<br />

were other serious divisions as well. Other regions, such as the West, and<br />

other groups, such as Aboriginal peoples, were increasingly determined to<br />

make their voices heard.<br />

The next initiative to forge a national consensus came from the<br />

provincial premiers. Although Québec’s premier, Lucien Bouchard,<br />

refused to attend, in September 1997, nine provincial premiers met in<br />

Calgary in an attempt to lay the groundwork for a unity package that they<br />

hoped would be supported by the majority of Canadians. The Calgary<br />

Declaration, as the agreement came to be known, declared that<br />

• Québec should be recognized as a unique society, and that the<br />

Government of Québec has a role in preserving the unique character of<br />

the province<br />

• all Canadians are equal and all provinces have equal status<br />

• Canada’s multicultural diversity includes Aboriginal peoples and<br />

citizens from all parts of the world<br />

• any future constitutional amendments would apply equally to all<br />

provinces<br />

Although the Calgary Declaration was endorsed by Prime Minister<br />

Jean Chrétien, it did little to resolve Canada’s constitutional woes.<br />

Aboriginal leaders, for example, were disappointed that the agreement did<br />

not fully address their concerns.<br />

Bouchard rejected the declaration, stating that it was meaningless<br />

to suggest that the Québécois were unique like all other Canadians,<br />

and in Québec, the declaration quickly lost credibility. In response to<br />

the Calgary Declaration, Bouchard issued a statement to the people of<br />

Québec, which read, in part<br />

WEB CONNECTIONS<br />

To read the entire speech given by Premier<br />

Bouchard in response to the Calgary<br />

Declaration, go to the Shaping Canada<br />

web site and follow the links.<br />

Two years ago, 49.4% of Quebecers voted in favour of sovereignty. This jolt<br />

was not sufficient to earn Québec respect and recognition, much less control<br />

over its affairs. Two years ago, we mobilized all of our energies to send our<br />

neighbours the broadest appeal for change in our history.<br />

Sunday, in Calgary, the English-speaking premiers were clear. Canada will not<br />

make any of the changes sought by Quebecers . . ..<br />

The premiers have shown, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that if Quebecers<br />

want to be recognized as the people they are, if they wish to control their<br />

destiny, there is only one course of action open to them, i.e. for a majority of<br />

them to vote next time for sovereignty . . ..<br />

HP Why did Québec Premier Lucien Bouchard state that the Calgary<br />

Declaration showed that Canada would not make any of the changes that<br />

Québec wanted<br />

470 Cl u s t e r 5 • Defining Contemporary Canada (1982 to present) • m h r

V i e w p o i n t s o n Hi s t o r y<br />

The Right to Be a Distinct Society<br />

The question of whether Québec should be recognized as a distinct society has dominated<br />

national unity discussions. This question generated many different reactions. Read the<br />

following viewpoints regarding the idea of a distinct society.<br />

Th e Li b e r a l Pa r t y o f Qu é b e c, in its policy statement<br />

Mastering Our Future, 1985:<br />

It is high time that Québec be given explicit constitutional<br />

recognition as a distinct society, with its own language,<br />

culture, history, institutions and way of life. Without this<br />

recognition, and the accompanying political rights and<br />

responsibilities, it will always be difficult to agree on the<br />

numerous questions involving Québec’s place in Canada.<br />

This recognition should be formally expressed in a preamble<br />

of the new Constitution.<br />

Grand Chief Ph i l Fo n t a i n e , head of the Assembly of<br />

Manitoba Chiefs, 1989–1997, in the Montréal Gazette,<br />

June 18, 1990:<br />

. . . if Québec is distinct, we are even more distinct. That’s<br />

the recognition we want, and will settle for nothing less . . ..<br />

Like Québec, we want to be recognized as a distinct society,<br />

because recognition means power . . . the ability to make<br />

laws that will govern our communities and we want a<br />

justice system that is more compatible with the traditions<br />

of our people.<br />

Former prime minister Pi e r r e Tr u d e a u in the<br />

Montréal Gazette, February 17, 1996:<br />

I have always opposed the notions of special status and<br />

distinct society. With the Quiet Revolution, Québec became<br />

an adult and its inhabitants have no need of favours or<br />

privileges to face life’s challenges and to take their rightful<br />

place within Canada and in the world at large. They should<br />

not look for their “identity” and their “distinctness” in the<br />

constitution, but rather in their confidence in themselves<br />

and in the full exercise of their rights as citizens equal to all<br />

other citizens of Canada.<br />

Br i a n Di c k s o n, chief justice of the Supreme Court<br />

of Canada, in a speech on Québec as a distinct<br />

society, 1996:<br />

Let me say directly that I have no difficulty with the<br />

concept [of distinct society]. In fact, the courts are already<br />

interpreting the Charter of Rights and the Constitution in a<br />

manner that takes into account Québec’s distinctive role in<br />

protecting and promoting its francophone character . . ..<br />

[T]herefore entrenching formal recognition of Québec’s<br />

distinctive character in the Constitution would not involve a<br />

significant departure from the existing practise in our court.<br />

Ex p l o r a t i o n s<br />

1. Summarize the arguments of those opposed to<br />

Québec being granted a distinct society status, then<br />

summarize the arguments of those who support<br />

Québec’s distinct society status.<br />

2. Many Canadians outside Québec had strong opinions<br />

HP about Québec’s status as a distinct society. Take the<br />

historical perspective of a Canadian outside of Québec<br />

in 1992 and speculate why he or she might have agreed<br />

or disagreed with this recognition. You may want to<br />

review <strong>Chapter</strong>s 12 to 15 to examine the events and<br />

issues that may have affected her or his opinion.<br />

m h r • National Unity • Ch a p t e r <strong>16</strong><br />

471

the Right to Secede<br />

In 1998, the Parti Québécois was re-elected in Québec. The federal<br />

government decided it had to do more than just react to further moves<br />

toward separation by Québec. In 1999, the government went to the<br />

Supreme Court of Canada to seek legal guidelines in case Québec declared<br />

that it would secede (formally withdraw) from the federation. The<br />

government asked, “Under the Constitution of Canada, can the National<br />

Assembly, legislature, or government of Québec effect the succession of<br />

Québec from Canada unilaterally [without consultation with Canada]”<br />

The Supreme Court said it could not. It stated that Québec was legally<br />

bound to negotiate with Canada on the terms of any separation.<br />

The Canadian government also asked the court whether Québec had<br />

the right to declare independence unilaterally under international law.<br />

Again, the Court said no. The federal government then turned to the<br />

Québec government and asked it to respect the court’s ruling.<br />

The Québec government chose to see support for Québec<br />

independence in the ruling. Québec stated that, should there be a<br />

favourable vote for sovereignty, the ruling obliges Canada to negotiate<br />

in good faith with Québec.<br />

Figure <strong>16</strong>-10 Our Master of Clarity, by<br />

Aislin, 1999. Prime Minister Jean Chrétien,<br />

who was often criticized for his lack of<br />

clarity, was the subject of many editorial<br />

cartoons when he passed the Clarity Act.<br />

Clarity Act<br />

As the Supreme Court ruling on Québec’s right to secede did not settle<br />

all of the separation issues, the Canadian government decided it was<br />

time to try to end the uncertainty about Québec separation. In 1999, the<br />

Chrétien government began drafting the Clarity Act, which it passed<br />

in 2000. The act established the following requirements for any future<br />

separation referendums held in any province:<br />

• Before a vote, the House of Commons will decide whether the<br />

proposed referendum question is clear. Furthermore, any question that<br />

goes beyond the basic issue of separation will be considered unclear.<br />

• After the vote, the House of Commons will decide whether a clear<br />

majority has been achieved—50 percent plus one may not be accepted<br />

as enough support for separation.<br />

• All provinces and Aboriginal peoples will be part of the discussions.<br />

• A constitutional amendment is required before a province can separate.<br />

Gilles Duceppe, the new leader of the Bloc Québécois, fought the<br />

Clarity Act. He said it gave the federal government too much power to<br />

interfere with Québec. Despite his efforts, Parliament passed the act on<br />

June 29, 2000.<br />

Recall . . . R e f l e c t . . . R e s po n d<br />

1. Create a timeline that includes four or five events in<br />

HS the history of the constitutional debate from 1989 to<br />

the present. For each event on the timeline, add a<br />

note explaining the event’s historical significance.<br />

2. Find a current news story that reflects how<br />

C&C Canada’s founding nations—Aboriginal peoples,<br />

French, and English—continue to influence the<br />

country’s politics today. Explain your choice.<br />

472 Cl u s t e r 5 • Defining Contemporary Canada (1982 to present) • m h r

HS<br />

Establishing establishing Historical historical significance<br />

Significance<br />

A Nation within a United Canada<br />

I think tonight was an historic night. Canadians across the country said “yes” to Québec, “yes” to<br />

Québecers, and Québecers said “yes” to Canada.<br />

— Prime Minister Stephen Harper, on passing the motion declaring the<br />

Québécois as a nation within a united Canada, November 27, 2006<br />

The popularity of the sovereignty movement in<br />

Québec has gone up and down since 2000, but the<br />

movement remains strong among many Québécois. In<br />

November 2006, the Bloc Québécois asked the House<br />

of Commons to pass a motion recognizing “Québecers<br />

as a nation.” Many Members of Parliament (MPs)<br />

objected, saying the motion did not include a<br />

reference to Canada. In response, Prime Minister<br />

Harper introduced a motion that stated, “That this<br />

House recognize that the Québécois form a nation<br />

within a united Canada.”<br />

In his address to the House of Commons, Harper<br />

stated his government’s position on the motion:<br />

HS<br />

Our position is clear—do the Québécois form a<br />

nation within Canada<br />

The answer is yes.<br />

Do the Québécois form an independent nation<br />

The answer is no.<br />

And the answer will always be no.<br />

Although the Bloc Québécois wanted to change<br />

the wording to state that the “Québécois are a nation<br />

currently within Canada,” they later accepted Harper’s<br />

motion. On November 27, 2006, the House of Commons<br />

passed the motion by a vote of 266 to <strong>16</strong>, with support<br />

from the majority of Conservative, Liberal, New<br />

Democrat, and Bloc Québécois MPs.<br />

1. Why was the recognition of the Québécois as a nation<br />

within a united Canada historically significant Did<br />

Parliament’s approval of the motion suggest that<br />

Canadians might be ready to recognize Québec<br />

as a distinct society Explain the reasons for your<br />

judgment.<br />

Despite the overwhelming support for the motion,<br />

Conservative MP Michael Chong, the minister of<br />

intergovernmental affairs and minister of sport,<br />

announced his resignation from his position so he<br />

could abstain from voting. Chong stated that the motion<br />

was “. . . nothing else but the recognition of ethnic<br />

nationalism, and that is something I cannot support. It<br />

cannot be interpreted as the recognition of a territorial<br />

nationalism, as it does not refer to the geographic entity,<br />

but to a group of people.” Other MPs stated that the<br />

motion was divisive, further damaging national unity.<br />

Figure <strong>16</strong>-11 When federal politicians were debating whether<br />

Québécois form a nation within Canada, Michael de Adder drew this<br />

cartoon to reflect his views on the recurring issue of Canadian unity.<br />

Why might some Canadians have taken this view of the debate<br />

2. Review Michael Chong’s statement about the motion.<br />

Do you think his opposition reflected the views of many<br />

Canadians Do you think the motion had an effect on<br />

national unity Explain your answer.<br />

m h r • National Unity • Ch a p t e r <strong>16</strong><br />

473

Na t i o n a l Un i t y a n d Ch a n g i n g Po l i t i c s<br />

Figure <strong>16</strong>-12 Reform Party leader Preston<br />

Manning is shown with some of the<br />

party’s campaign materials, including<br />

a party newspaper that carried the<br />

headline “What does the West want”<br />

What demands might the article have<br />

included<br />

“The West Wants In”<br />

In the 1980s many in the western provinces—Manitoba, Saskatchewan,<br />

Alberta, and British Columbia—felt a growing sense of alienation from<br />

the rest of Canada. Many western Canadians were tired of being left out<br />

of the federal government’s priorities and believed that Ottawa did not<br />

understand or appreciate their needs. These feelings of western alienation<br />

led to the creation of several new political parties.<br />

The Reform Party<br />

In 1987, the creation of the Reform Party of Canada was a result<br />

of western alienation. The party’s slogan was “The West wants<br />

in.” Preston Manning, an Albertan and the Reform Party’s first<br />

leader, called for provincial equality with no special status for<br />

Québec. The party came to national attention in 1993 when it<br />

campaigned against the Charlottetown Accord in the federal<br />

election and won fifty-two seats in the House of Commons.<br />

Then, in the 1997 federal election, the party increased its seats<br />

to sixty, and Manning became the leader of the opposition.<br />

All the members of the Reform Party were from the West, and<br />

the party was viewed as a regional party. Knowing it would<br />

have to increase the Reform Party’s size and scope of members<br />

beyond the West if it wanted to get enough votes to form the<br />

government, Manning started a movement called the United<br />

Alternative. Its goal was to “unite the right” and create a new<br />

conservative party with a national political base.<br />

A New Conservative Party<br />

In an attempt to persuade Progressive<br />

Conservative Party members to join them,<br />

members of the Reform Party voted in 2000<br />

to dissolve their party and create the Canadian<br />

Alliance. In 2002, Stephen Harper, a Calgary<br />

politician, was elected leader of the Alliance party.<br />

In 2003, the Canadian Alliance merged with<br />

the Progressive Conservative Party. Together,<br />

they formed the Conservative Party of Canada,<br />

and Harper was elected as the party’s leader. In<br />

the 2006 federal election, the Conservative Party<br />

formed a minority government.<br />

Figure <strong>16</strong>-13 In 1992, Montréal cartoonist Aislin created<br />

this cartoon, which used negative stereotypes to show the<br />

growing gap in understanding between Québécois and<br />

western Canadians. How might this gap in understanding<br />

affect national unity debates in Canada<br />

474 Cl u s t e r 5 • Defining Contemporary Canada (1982 to present) • m h r

Federal–Provincial Division of Powers<br />

As the federal government struggled with trying to keep Canada<br />

united, it also faced several challenges from provincial governments.<br />

Since Confederation, the division of powers between the federal and<br />

provincial governments has been at the root of many conflicts. As you<br />

learned in <strong>Chapter</strong> 14, one of the major concerns between the federal and<br />

provincial governments was over the control of resources. While provinces<br />

continue to retain significant control over their resources, they must<br />

also increasingly work with federal environmental policies, such as those<br />

regarding reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and sustainability.<br />

Other issues in which the division of power has to led to debate<br />

include equalization payments and health care.<br />

Equalization Payments<br />

When Canada was formed in 1867, the provinces were given responsibility<br />

for social programs. Inequalities occurred because rich provinces could<br />

provide more services to their residents than less-prosperous provinces.<br />

In 1957, Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent persuaded prosperous<br />

provinces to share some of their wealth. St. Laurent’s goal was to ensure that<br />

all Canadians would have access to similar public services, no matter what<br />

province they lived in. To achieve this, wealthier provinces, such as Ontario<br />

and British Columbia, gave some of the money they collected in taxes to the<br />

federal government. The government then redistributed this money to the<br />

less-prosperous provinces in a transfer known as equalization payments.<br />

The federal government calculates the amount of equalization<br />

payments in consultation with the provinces. Many provincial leaders<br />

question the program. The issues include fairness, level of services, natural<br />

resource revenues, and how equalization payments are calculated.<br />

C C<br />

Due to the economic downturn in 2008, Ontario became a recipient<br />

of equalization payments for the first time since the program began. Do<br />

you think a change such as this would have any effect on support for<br />

national unity among the provinces Why or why not<br />

Figure <strong>16</strong>-14 Federal Equalization Payments to Provinces (millions of dollars)<br />

What factors do you think contribute to the amount of equalization payments going to<br />

each province<br />

Voices<br />

I haven’t chatted with any premier<br />

that thinks equalization is working<br />

well. That’s a part of the Canadian<br />

condition. Developing consensus<br />

on how to fix it—that’s nearly<br />

as complicated as amending the<br />

Constitution.<br />

— Ontario Premier<br />

Dalton McGuinty, 2010<br />

Let’s Discuss<br />

How might equalization payments<br />

create friction between provinces and<br />

affect national unity<br />

2007–08 2008–09 2009–10 2010–11 2011–12<br />

8000<br />

7000<br />

6000<br />

5000<br />

4000<br />

3000<br />

2000<br />

1000<br />

0<br />

NF<br />

PEI<br />

NS<br />

NB<br />

QC<br />

ON<br />

MB<br />

SK<br />

AB<br />

BC<br />

NF<br />

PEI<br />

NS<br />

NB<br />

QC<br />

ON<br />

MB<br />

SK<br />

AB<br />

BC<br />

NF<br />

PEI<br />

NS<br />

NB<br />

QC<br />

ON<br />

MB<br />

SK<br />

AB<br />

BC<br />

NF<br />

PEI<br />

NS<br />

NB<br />

QC<br />

ON<br />

MB<br />

SK<br />

AB<br />

BC<br />

NF<br />

PEI<br />

NS<br />

NB<br />

QC<br />

ON<br />

MB<br />

SK<br />

AB<br />

BC<br />

Source: Department of Finance Canada<br />

m h r • National Unity • Ch a p t e r <strong>16</strong><br />

475

Figure <strong>16</strong>-15 Roy Romanow holds a copy<br />

of his report regarding the future of<br />

health care in Canada. Why do you think<br />

it was called Building on Values <br />

Health-Care Issues<br />

The health-care system is another point of contention between the federal<br />

and provincial governments. Health care in Canada has undergone many<br />

changes since medicare was introduced in 1966. Costs of<br />

public health care have risen dramatically, and the federal<br />

and provincial governments have frequently disagreed<br />

over how health care is funded and how health-care funds<br />

are spent.<br />

By 2001, funding for universal health care had fallen<br />

behind the rising costs. Some hospitals closed while<br />

others offered limited services. Some provinces moved<br />

toward a two-tier health system and allowed for-profit,<br />

private-sector businesses to offer some health-care<br />

procedures. This meant that those who could afford to<br />

pay for procedures with their own money could obtain<br />

some health services before other people.<br />

Public opinion polls showed that Canadians<br />

wanted to keep universal health care, but they wanted<br />

improvements. In response, Prime Minister Jean<br />

Chrétien appointed former Saskatchewan premier Roy<br />

Romanow to head the Commission on the Future of<br />

Health Care in Canada.<br />

In November 2002, Romanow released a 356-page<br />

report, which became known as the Romanow Report.<br />

Among its forty-seven recommendations, the report<br />

stated that<br />

• provinces and territories should work together with the federal<br />

government to maintain universal health care for all Canadians<br />

• the federal government should increase contributions to medicare<br />

• governments should be more accountable about how funds are being<br />

spent on health care<br />

• a national drug plan should be developed to help offset the rising costs<br />

of prescription medications<br />

• there should be increased funding and support for Aboriginal health<br />

care<br />

In response to the report, the federal government acted on some of<br />

the recommendations, such as injecting more funds into health care, but<br />

the tension between federal and provincial governments over the spending<br />

and allocation of funds has continued. Critics of the report argue that<br />

many of the recommendations, such as a national drug plan, are too<br />

expensive.<br />

C C What might be the consequences of provinces assuming more control<br />

over health care<br />

476 Cl u s t e r 5 • Defining Contemporary Canada (1982 to present) • m h r

Senate Reform<br />

Since 1982, successive Canadian governments have attempted Senate<br />

reform. Many Canadians have questioned the effectiveness of the Senate,<br />

which was created as a place of “sober second thought” on the decisions<br />

of the House of Commons. Many Canadians have argued that senators<br />

should be elected rather than appointed, should more closely reflect<br />

the cultural diversity of Canada, and should represent the population<br />

distribution across various provinces. Another major issue has been the<br />

fact that senators are appointed by the Governor General, after being<br />

recommended by the prime minister, and are not elected by Canadian<br />

citizens.<br />

Some provincial premiers lobbied for Senate reform to allow for<br />

provincial representation through elected senators. If a province could<br />

elect its own senator, then that senator could lobby for the interests of his<br />

or her province. In the 1990s, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney attempted<br />

to include Senate reforms in both the Meech Lake and the Charlottetown<br />

Accords, but those reforms were lost when the accords<br />

failed. Preston Manning and the Reform Party<br />

vocalized the idea of provincial representation when<br />

they pushed for a “Triple-E” Senate:<br />

elected, equal, and effective. The Triple-E<br />

proposal suggested that representation for<br />

the Senate be more proportional to the<br />

population of the provinces.<br />

When Stephen Harper came to power<br />

as head of the Conservative Party in<br />

2006, he promised to reform the Senate.<br />

In May 2006, he introduced legislation<br />

that would limit new senators to eightyear<br />

terms. This was a significant change<br />

from existing legislation that required only<br />

that senators retire when they reached<br />

the age of seventy-five. Similar to what<br />

Preston Manning wanted in a Triple-E<br />

Senate, Harper also planned to introduce<br />

reform that would allow Senate members<br />

to be elected by their provinces. However,<br />

as of 2010, Senate members were still<br />

appointed by the Governor General upon<br />

recommendations by the prime minister.<br />

One reason that significant Senate<br />

reform has not taken place is that it<br />

requires a constitutional amendment. For an amendment to take place,<br />

seven provinces with at least 50 percent of the Canadian population must<br />

agree to the change. As you have learned through the Meech Lake and<br />

Charlottetown Accords, constitutional reform is not an easy task.<br />

CHECKBACK<br />

You learned about the roles of<br />

the Senate in <strong>Chapter</strong> 6.<br />

Figure <strong>16</strong>-<strong>16</strong> In 2010, Prime Minister<br />

Harper’s minority Conservative<br />

government tried—unsuccessfully—to<br />

pass motions in the House of Commons<br />

approving fixed, eight-year terms<br />

for senators. How does this cartoon<br />

represent this proposal for reform<br />

C C How would Senate reform affect the provinces and<br />

territories<br />

m h r • National Unity • Ch a p t e r <strong>16</strong><br />

477

Figure <strong>16</strong>-17 During the financial<br />

crisis of 2008 and 2009, many auto<br />

manufacturers closed plants. Manitoba<br />

was not hit as hard during the recession<br />

as provinces such as Ontario and Alberta,<br />

because its economy does not rely<br />

heavily on one industry or sector.<br />

Economic Recession and the<br />

Financial Crisis of 2008<br />

In September 2008, the economy of the United States entered a severe<br />

recession. Many banks and investment companies declared bankruptcy,<br />

the value of stocks plunged, and economists warned that the United States<br />

was moving into an economic depression. As you learned in <strong>Chapter</strong> 11,<br />

during economic depressions, business activity and prices drop,<br />

unemployment rises, and people do not have as much money to spend.<br />

Canada’s economy is closely linked to that of the United States.<br />

The United States is Canada’s biggest trading partner, with more than<br />

80 percent of Canadian exports shipped south of the border. When<br />

American consumers stopped buying Canadian products and American<br />

businesses reduced the amount of Canadian resources they bought,<br />

Canadian exports suffered. This drop in demand for Canadian products<br />

and resources led to significant job losses in Canada.<br />

Canadian<br />

stock markets are<br />

also closely linked<br />

to American and<br />

world markets.<br />

When the price<br />

of shares plunged<br />

on international<br />

stock markets,<br />

share prices on<br />

Canadian markets<br />

also fell. The value<br />

of Canadians’<br />

investments<br />

dropped,<br />

significantly<br />

reducing many<br />

people’s savings.<br />

Many<br />

Canadians,<br />

especially those<br />

in the auto and<br />

oil industries, lost<br />

their jobs. Unemployed workers do not buy as much, and this affects sales<br />

in other businesses. As their sales drop, these businesses may lay off more<br />

workers, and the cycle continues.<br />

Ontario, Alberta, and British Columbia were hit hardest during<br />

the economic recession, while Manitoba was less seriously affected. In<br />

2009, Manitoba’s economy grew slightly. This growth was largely due<br />

to its diversified economy and provincially-funded construction and<br />

improvement projects.<br />

478 Cl u s t e r 5 • Defining Contemporary Canada (1982 to present) • m h r

The Shifting Political Spectrum<br />

Following Pierre Trudeau’s exit from politics, the Liberal Party’s lengthy<br />

mandate came to an end. Over the next several decades, federal power<br />

shifted between Conservative and Liberal governments, new political<br />

parties altered the political balance, and some governments had the<br />

challenge of governing as minority governments.<br />

Mulroney’s Conservative Government<br />

When Brian Mulroney came to power as prime minister in 1984, he<br />

brought a different style to Canadian politics and a more businessfriendly<br />

attitude to government than that of former prime minister Pierre<br />

Trudeau. He attempted to reduce the huge national debt that Canada had<br />

amassed since the 1960s. He discontinued old age pensions and family<br />

allowances for citizens who could afford to live without government<br />

aid. The Mulroney government also triggered debates across Canada<br />

when it negotiated a free-trade deal with the United States and later with<br />

Mexico, introduced the Goods and Services Tax (GST), and made efforts<br />

to bring Québec into the Constitution through the Meech Lake and<br />

Charlottetown Accords.<br />

Despite winning majority governments in 1984 and 1988, when<br />

Mulroney left office in 1993, his popularity among Canadians was the<br />

lowest of any prime minister in Canadian history. In the election that<br />

followed his resignation, his Progressive Conservative Party was reduced<br />

to only two seats in Parliament, which resulted in the loss of its status as<br />

an official party in the House of Commons.<br />

Chr tien’s Liberal Governments<br />

Jean Chrétien, whose political career stretched back to<br />

the 1960s, became prime minister in 1993 as Canada<br />

headed into an economic boom. Prime Minister<br />

Chrétien’s government made drastic cuts to<br />

government spending and was able to bring<br />

Canada’s enormous public debt under control.<br />

Chrétien’s government and the Liberal Party<br />

began to lose popularity during the Sponsorship<br />

Scandal, which came to light in 2003 and 2004.<br />

After the 1995 Québec sovereignty referendum,<br />

Chrétien set up a special $250 million fund to fight<br />

separatism by sponsoring and advertising the idea of a<br />

united Canada in Québec. When stories of improper<br />

use of this money were reported in November 2003,<br />

Chrétien resigned, and Paul Martin took over as prime<br />

minister. In 2004, Canada’s auditor general, who<br />

examines the federal government’s accounts, found<br />

that $100 million in sponsorship funds had been<br />

given illegally to advertising companies with ties to the<br />

Liberal Party.<br />

CHECKFORWARD<br />

You will learn about Canada’s<br />

free-trade agreements with the<br />

United States and Mexico in<br />

<strong>Chapter</strong> 18.<br />

Figure <strong>16</strong>-18 CHECKBACK Jean Chrétien (left) and<br />

Paul Martin (right) were the prime<br />

ministers of Canada during the unbroken<br />

series of Liberal governments from<br />

1993 to 2006. Chrétien served as prime<br />

minister from 1993 to 2003, while Martin<br />

served from 2003 to 2006.<br />

m h r • National Unity • Ch a p t e r <strong>16</strong><br />

479

Figure <strong>16</strong>-19 In 2008, Stephen Harper’s<br />

Conservative Party formed Canada’s third<br />

minority government in four years.<br />

Figure <strong>16</strong>-20 Despite having candidates<br />

in all 308 Canadian ridings, it was not<br />

until the election of 2008, after much<br />

arguing among federal party leaders,<br />

that the Green Party was invited to<br />

participate in pre-election debates. In<br />

this photograph, Green Party Leader<br />

Elizabeth May responds to a question<br />

during a federal election debate in<br />

Ottawa on October 2, 2008.<br />

Minority Governments<br />

In the 2004 election, the Liberals lost seats, but they still managed to<br />

form a minority government. Minority governments have less power than<br />

majority governments and must negotiate with other parties for support to<br />

gain enough votes to pass laws and stay in power. If the opposition parties<br />

vote together, they can defeat a minority government and force an election.<br />

In 2005, opposition parties banded together and forced the Liberal Party<br />

to hold another federal election in January 2006. The opposition believed<br />

that the Liberals were losing support among Canadians and that Prime<br />

Minister Paul Martin’s government could be voted out. In this election,<br />

the Conservatives won enough seats to form a minority government, and<br />

Stephen Harper became prime minister.<br />

C C<br />

The Conservative Party formed a minority government in 2006 and<br />

2008. What do you think are some of the factors that led to the election<br />

of these minority governments What were some of the consequences<br />

Formation of the Green Party<br />

The political stage in Canada was also changed by the arrival of a new<br />

federal political party—the Green Party of Canada. The party was founded<br />

in 1983 and had grown to roughly 11 000 members by 2008. The Green<br />

Party is not affiliated with other green parties around the world, but it is<br />

similarly aligned in that it supports an economy that is environmentally<br />

responsible and a government that is accountable to its citizens.<br />

In the 2004 federal election, the Green Party made history when it became<br />

only the fourth federal political party ever to run candidates in all 308 ridings<br />

across Canada. Although<br />

the Green Party received just<br />

under one million votes in<br />

the election, it failed to win<br />

any seats in the House of<br />

Commons.<br />

Recall . . . R e f l e c t . . . R e s po n d<br />

1. Review pages 474 to 480 and choose two political<br />

HS changes that had the most significance for national<br />

unity. Provide arguments for why they were most<br />

significant.<br />

2. What challenges have caused the most tension in<br />

federal–provincial relations in Canada Why<br />

C C<br />

480 Cl u s t e r 5 • Defining Contemporary Canada (1982 to present) • m h r

ED<br />

considering Considering the ethical dimensions of history<br />

Proroguing Parliament<br />

In a federal election that marked the lowest voter turnout in Canadian history (59.1 percent), the<br />

Conservative Party formed yet another minority government in 2008. The opposition became<br />

convinced that if they forced another election, they could overturn the Harper government.<br />

The opposition announced that they would be<br />

declaring a non-confidence vote against the<br />

Conservative government on December 8, 2008. If<br />

a majority of Members of Parliament vote that they<br />

do not have confidence in the current government,<br />

then one of two courses of action must be taken: the<br />

leader of the party with the next highest number of<br />

seats must try to form a government, or the present<br />

government must dissolve Parliament and call for<br />

a general election. The opposition hoped their nonconfidence<br />

vote would force a new election.<br />

To avoid the non-confidence vote, Prime Minister<br />

Stephen Harper asked Governor General Michaëlle<br />

Jean to prorogue Parliament, as the official order must<br />

come from the Governor General. The prorogation of<br />

Parliament means that the legislature is discontinued<br />

for a period of time, but not dissolved completely.<br />

Jean agreed and called for the prorogation on<br />

December 4, 2008. By doing this, Harper avoided the<br />

non-confidence vote, but raised considerable debate<br />

among politicians and citizens who viewed the move<br />

as anti-democratic.<br />

In 2010, Harper once again asked the Governor<br />

General to prorogue Parliament for several weeks.<br />

The prorogation caused protests across Canada<br />

and from opposition party members. A group called<br />

“Canadians Against Proroguing Parliament” attracted<br />

over 200 000 members. Over 200 constitutional lawyers<br />

and political scientists signed a petition objecting<br />

to Harper’s use of prorogation “for a second year<br />

in a row in circumstances that allow him to evade<br />

democratic accountability.” While Harper stated<br />

that the decision to prorogue Parliament was to give<br />

his party time to consult with Canadians about the<br />

economy, many opposition leaders believed it was done<br />

to avoid accountability for the treatment of Afghanistan<br />

detainees by Canadian forces during the United<br />

Nations mission in Afghanistan. You will learn about the<br />

Canadian forces in Afghanistan in <strong>Chapter</strong> 18.<br />

Public opinion polls after the second prorogation<br />

of Parliament showed that 53 percent of those<br />

polled disagreed with Harper’s request to prorogue<br />

Parliament.<br />

Figure <strong>16</strong>-21 On January 23, 2010, protestors in Toronto rallied<br />