This amorphous selection of Anatolian village pile rugs, prayer ... - Hali

This amorphous selection of Anatolian village pile rugs, prayer ... - Hali

This amorphous selection of Anatolian village pile rugs, prayer ... - Hali

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Photo by Longevity, London<br />

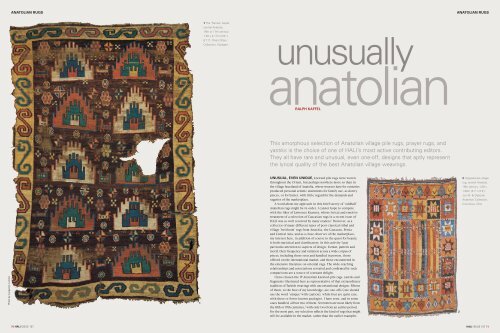

ANATOLIAN RUGS<br />

70 HALI ISSUE 157<br />

1<br />

1 The ‘Flames’ carpet,<br />

central Anatolia,<br />

16th or 17th century.<br />

1.45 x 2.11m (4'9" x<br />

6'11"). Orient Stars<br />

Collection, Stuttgart<br />

unusually<br />

anatolian<br />

RALPH KAFFEL<br />

<strong>This</strong> <strong>amorphous</strong> <strong>selection</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Anatolian</strong> <strong>village</strong> <strong>pile</strong> <strong>rugs</strong>, <strong>prayer</strong> <strong>rugs</strong>, and<br />

yastıks is the choice <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> HALI’s most active contributing editors.<br />

They all have rare and unusual, even one-<strong>of</strong>f, designs that aptly represent<br />

the lyrical quality <strong>of</strong> the best <strong>Anatolian</strong> <strong>village</strong> weavings.<br />

UNUSUAL, EVEN UNIQUE, knotted <strong>pile</strong> <strong>rugs</strong> were woven<br />

throughout the Orient, but perhaps nowhere more so than in<br />

the <strong>village</strong> heartland <strong>of</strong> Anatolia, where weavers have for centuries<br />

produced personal artistic statements for family use, as dowry<br />

pieces, or for barter, with little regard for the demands and<br />

vagaries <strong>of</strong> the marketplace.<br />

A word about my approach in this brief survey <strong>of</strong> ‘oddball’<br />

<strong>Anatolian</strong> <strong>rugs</strong> might be in order. I cannot hope to compete<br />

with the likes <strong>of</strong> Lawrence Kearney, whose lyrical and emotive<br />

treatment <strong>of</strong> a <strong>selection</strong> <strong>of</strong> Caucasian <strong>rugs</strong> in a recent issue <strong>of</strong><br />

HALI was so well received by many readers. 1 However, as a<br />

collector <strong>of</strong> many different types <strong>of</strong> post-classical tribal and<br />

<strong>village</strong> ‘heirloom’ <strong>rugs</strong> from Anatolia, the Caucasus, Persia<br />

and Central Asia, and as a close observer <strong>of</strong> the marketplace,<br />

my interest here, in addition <strong>of</strong> course to the quest for beauty,<br />

is both statistical and classificatory. In this activity I pay<br />

particular attention to aspects <strong>of</strong> design, format, pattern and<br />

motif, their frequency and variation across a wide corpus <strong>of</strong><br />

pieces, including those seen and handled in person, those<br />

<strong>of</strong>fered on the international market, and those encountered in<br />

the extensive literature on oriental <strong>rugs</strong>. The wide-reaching<br />

relationships and associations revealed and confirmed by such<br />

comparisons are a source <strong>of</strong> constant delight.<br />

I have chosen the 19 <strong>Anatolian</strong> knotted-<strong>pile</strong> <strong>rugs</strong>, yastıks and<br />

fragments illustrated here as representative <strong>of</strong> that extraordinary<br />

tradition <strong>of</strong> Turkish weavings with unconventional designs. Fifteen<br />

<strong>of</strong> them, to the best <strong>of</strong> my knowledge, are one-<strong>of</strong>fs (one should<br />

use the word ‘unique’ with caution), while four are quite rare,<br />

with three or fewer known analogies. I have seen, and in some<br />

cases handled, all but two <strong>of</strong> them. Seventeen are most likely from<br />

the 18th or 19th centuries, 2 with only two from an earlier period.<br />

For the most part, my <strong>selection</strong> reflects the kind <strong>of</strong> <strong>rugs</strong> that might<br />

still be available in the market, rather than the earlier examples<br />

ANATOLIAN RUGS<br />

2<br />

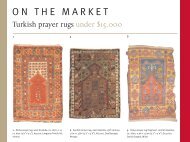

2 Cappadocian <strong>village</strong><br />

rug, central Anatolia,<br />

19th century. 1.09 x<br />

1.60m (3'7" x 5'3").<br />

Jon M. & Deborah<br />

Anderson Collection,<br />

Columbus, Ohio<br />

HALI ISSUE 157 71

ANATOLIAN RUGS<br />

Photo by Dennis Anderson<br />

72 HALI ISSUE 157<br />

3<br />

3 West <strong>Anatolian</strong><br />

<strong>village</strong> rug, before<br />

1800. 1.37 x 1.98m<br />

(4'6" x 6'6"). Jim<br />

Dixon Collection,<br />

Occidental, California<br />

4 West (?) <strong>Anatolian</strong><br />

yastık, 19th century.<br />

0.58 x 0.86m (1'11" x<br />

2'10"). Bethany Mendenhall<br />

Collection,<br />

Irvine, California<br />

5 Konya yastık,<br />

central Anatolia,<br />

dated 1287 AH<br />

(1870 AD). 0.58 x<br />

0.89m (1'11" x 2'11").<br />

Gilbert & Hillary<br />

Dumas Collection,<br />

Kensington,<br />

California<br />

that are mainly limited to museum holdings or to venerable<br />

private collections. The two early <strong>rugs</strong>, 1 and 18, are indulgences,<br />

as they are my personal favourites.<br />

A Konya <strong>prayer</strong> rug without known comparisons is the perfect<br />

introduction to this ‘<strong>amorphous</strong>’ group <strong>of</strong> <strong>Anatolian</strong> pieces cover.<br />

Woven before 1800, its simple, angular design emphasises the<br />

quality and intensity <strong>of</strong> saturated colour that epitomises old Konya<br />

<strong>village</strong> weavings. The rug was in the San Francisco Bay Area trade<br />

prior to its purchase by the Milanese dealer Alberto Levi, who<br />

used a detail <strong>of</strong> it for the cover <strong>of</strong> his inaugural catalogue in<br />

2000, with this comment: “A rare and unusual <strong>village</strong> rug with<br />

a niche design on a yellow background, the niche created by<br />

simple lines that carve into the red field, skillfully punctuated<br />

by eight-petalled rosettes both inside the niche and flanking it<br />

near its cusp. An interesting crescendo rhythm is adopted for<br />

the border, culminating in a sort <strong>of</strong> canopy <strong>of</strong> lozenges highlighted<br />

by the oxidation <strong>of</strong> the brown wool, reminding us <strong>of</strong><br />

the shape <strong>of</strong> kapunuk trappings <strong>of</strong> the Turkoman tribes.” 3<br />

Another apparently ‘unique’ rug, the so-called ‘Flames’ carpet 1,<br />

was available in October 1994 at Konya’s famous Young Partners<br />

shop, described by Cemal Palamutçu as a 16th century Sivas, at a<br />

price which strongly suggested that only serious collectors with<br />

substantial financial resources need apply. It was soon acquired<br />

by the late Heinrich Kirchheim and was exhibited in 1995 in an<br />

augmented ‘Orient Stars’ display held at Museum Schloss Rheydt<br />

in Moenchengladbach. 4 The Sivas attribution may be questionable;<br />

central Anatolia is the more likely place <strong>of</strong> origin, but its age<br />

(17th century or earlier), beauty and importance are beyond<br />

doubt. No comparable knotted-<strong>pile</strong> example is known, but<br />

the style <strong>of</strong> the ten ascending turreted motifs bears a strong<br />

relationship to the multiple <strong>prayer</strong> niches <strong>of</strong> certain ancient<br />

<strong>Anatolian</strong> kilims. 5 A similar border <strong>of</strong> bold ‘S’ shapes appears<br />

on an 18th century Kazak rug in Kirchheim’s Orient Stars. 6<br />

A beautifully colourful little 19th century Cappadocian <strong>village</strong><br />

5<br />

rug 2 from the collection <strong>of</strong> the late Jon M. (Mac) Anderson in<br />

Columbus, Ohio, was first seen during the 2002 ACOR exhibition<br />

‘Rugs <strong>of</strong> Rare Beauty from Midwestern Collections’ in Indianapolis.<br />

7 Very much like a yastık (pillow or cushion face) in design<br />

and proportions, it is akin to another Central <strong>Anatolian</strong> piece<br />

from the Dennis Dodds Collection, about which Brian Morehouse<br />

has written: “<strong>This</strong> yastık is uncharacteristic in the allocation <strong>of</strong><br />

the small amount <strong>of</strong> space to the striped field in proportion to<br />

the large border and end panel areas”, 8 a statement that applies<br />

equally to the present rug. The wide border here is composed <strong>of</strong><br />

‘Solomon’ stars enclosed within polychrome rectangles. Similar<br />

eight-pointed stars appear on a red-ground border on another <strong>of</strong><br />

the yastıks published by Morehouse. 9 Perhaps the closest comparison<br />

among <strong>rugs</strong> is a runner with a border <strong>of</strong> stars on a black<br />

ground in the collection <strong>of</strong> Dr Ayan Gülgönen in Istanbul. 10<br />

The vast Jim Dixon Collection, now mostly kept in Occidental,<br />

California, contains a number <strong>of</strong> highly unusual pieces, two <strong>of</strong><br />

which are featured in this survey. One <strong>of</strong> them is a pre-1800 west<br />

<strong>Anatolian</strong> <strong>village</strong> rug that, while composed <strong>of</strong> familiar elements,<br />

has no close parallels in the literature 3. Previously published<br />

in 2000 in Murray Eiland’s HALI article on Dixon’s collection, 11<br />

its central ‘re-entrant’ panel is related to those seen on the<br />

‘hearth’ <strong>rugs</strong> <strong>of</strong> Bergama12 and on later Bergama <strong>rugs</strong>, 13 as well as<br />

to certain 16th/17th century Holbein pattern carpets attributed to<br />

the Konya district. 14 However, its most uncommon feature is the<br />

disproportionately wide lateral meander border, which is closely<br />

similar to that on a well-known 16th/17th century Konya ‘animal<br />

pelt’ <strong>prayer</strong> rug in the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum (TIEM),<br />

Istanbul. 15 In the 19th century similar wide meander borders were<br />

adopted by Melas weavers. 16<br />

A charming 19th century yastık 4 from the Bethany Mendenhall<br />

Collection in Irvine, California, was exhibited during the 2007<br />

Istanbul ICOC. 17 Probably made in western Anatolia, it is one <strong>of</strong><br />

only two published weavings in which the classic Ladik border<br />

design <strong>of</strong> tulips and carnations is adapted to create an all-over<br />

field pattern, the other being a well-known ivory-ground rug,<br />

formerly in the Kinebanian Collection in Holland, first published<br />

by Ulrich Schürmann, 18 who remarked <strong>of</strong> this field design:“…how<br />

much rarer…in a carpet like this one…which could have come<br />

from Konya and in which the whole inner panel is covered with<br />

the kind <strong>of</strong> repeating pattern normally only found in the border”.<br />

Among yastıks, the nearest analogies I can find are three examples<br />

with a field pattern <strong>of</strong> stylised geometric rosettes enclosed by<br />

leaves, 19 while among <strong>rugs</strong> there are Konya examples with fields<br />

<strong>of</strong> similar rosettes in a repeat pattern (and one with tulips in the<br />

corners), 20 but none <strong>of</strong> them have either white grounds or the<br />

alternating pattern <strong>of</strong> rosettes and tulips. 21<br />

A rare Konya yastık belonging to San Francisco Bay Area<br />

collectors Hillary and Gilbert Dumas 5, was selected for the<br />

cover <strong>of</strong> the catalogue accompanying the exhibition ‘Trefoil: Guls,<br />

Stars & Gardens’, held at the Mills College Art Gallery in<br />

Oakland in early 1990. 22 Inscribed and dated 1287 AH (1870 AD),<br />

nothing quite like it was known until 1995, when a closely similar<br />

but undated example, assigned to the first half <strong>of</strong> the 19th century,<br />

was advertised by the late Massachusetts dealer Basha Ahamed. 23<br />

The authors <strong>of</strong> the Trefoil catalogue point to the similarity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

star motif to the design <strong>of</strong> the ubiquitous ‘Seljuk’ star seen on the<br />

early carpets found in Konya and Beyshehir, as well as in classical<br />

large-pattern ‘Holbein’ carpets, Star Ushak carpets, and their<br />

descendants. 24 Similar stars also appear in other 19th century<br />

yastıks, although not in an over-all pattern. 25<br />

The memory <strong>of</strong> the funkiness and ‘unique’ design <strong>of</strong> a pre-1800<br />

Konya <strong>prayer</strong> rug 6 with an abrashed field (green above, blue<br />

below) belonging to the Massachusetts collector Gerard Paquin<br />

has stayed with me ever since I first saw it in April 2002 at ACOR 6<br />

in Indianapolis during his ‘From the Cedar Chest’ session. Woven<br />

in two pieces on a narrow loom, with each half having selvedges<br />

on both sides, it was an immediate choice for this survey. The<br />

depiction <strong>of</strong> hands, commonplace in Baluch and Caucasian <strong>prayer</strong><br />

Photo by Don Tuttle<br />

<strong>rugs</strong>, is very rare in Turkish ones. How rare? My index <strong>of</strong> Turkish<br />

<strong>prayer</strong> <strong>rugs</strong> contains more than 4,000 images, <strong>of</strong> which only six,<br />

all from eastern Anatolia, depict pairs <strong>of</strong> hands. 26<br />

The pr<strong>of</strong>usion <strong>of</strong> dots in the field <strong>of</strong> this rug may be perceived<br />

as depicting an animal pelt, although Paquin suggests that they<br />

may be apotropaic, meant to ward <strong>of</strong>f evil, and represent part <strong>of</strong><br />

the çintamani design. 27 The little strips <strong>of</strong> mosaic tile-like patterning<br />

between the field and the main horizontal borders are a unique<br />

feature in my experience, as are the two narrow red strips flanking<br />

the field. The border motif is known from a number <strong>of</strong> central<br />

<strong>Anatolian</strong> <strong>rugs</strong>, 28 but it does not appear on any <strong>prayer</strong> format pieces<br />

from the area. The outer guard border design repeats in the centre<br />

<strong>of</strong> the top and bottom borders.<br />

While the focus <strong>of</strong> this survey is on unusual designs rather<br />

than structural features, Paquin has kindly provided me with<br />

some fascinating structural information. The rug is ‘wefty’ with<br />

between five and nine undyed shoots between each row <strong>of</strong> large<br />

knots (18 per square inch), rather like a tülü weave. The wefts are<br />

S-spun, which is something that he has never seen in a Turkish<br />

<strong>village</strong> rug. Some sections <strong>of</strong> weft are dyed green and yellow,<br />

and appear to be <strong>of</strong> goat hair. Paquin believes that it is “… a folk<br />

expression, a vision <strong>of</strong> a <strong>prayer</strong> rug and its elements from someone<br />

who has been to a city mosque, but who is steeped in the<br />

traditions <strong>of</strong> the countryside, its beliefs and folkways”.<br />

The much-missed Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Charles Lave’s brief obituary in<br />

HALI 156 mentioned his “highly individual, even quirky, taste”. 29<br />

An 18th/19th century central <strong>Anatolian</strong> <strong>prayer</strong> rug is a prime<br />

example 7. Like the Paquin rug above, I first saw it during an ACOR<br />

Cedar Chest’ session, this time conducted by Charles and his<br />

wife Bethany Mendenhall in Seattle in March 2004. Like that <strong>of</strong><br />

the Paquin rug, the image <strong>of</strong> this rug has stayed in my mind.<br />

Charles called it his ‘Devil rug’, and the very unusual pale<br />

purple motif in the lower half <strong>of</strong> the field has an ominous look<br />

to it. Perhaps it was intended by the weaver to be a large amulet<br />

for protection from the evil eye. 30 It may be inferred from the<br />

three red minarets in the upper panel that this was an attempt to<br />

replicate a more formal ‘columned’ rug, albeit one without known<br />

4 6<br />

ANATOLIAN RUGS<br />

6 Konya <strong>prayer</strong> rug,<br />

central Anatolia,<br />

before 1800. Woven<br />

in two pieces,<br />

1.27 x 1.73m (4'2" x<br />

5'8"). Gerard Paquin<br />

Collection, Northampton,<br />

Massachusetts<br />

HALI ISSUE 157 73

ANATOLIAN RUGS<br />

7 The ‘Devil’ <strong>prayer</strong><br />

rug, central Anatolia,<br />

18th/19th century.<br />

1.23 x 1.63m (4'0"<br />

x 5'4"). Charles Lave<br />

Collection, Irvine,<br />

California<br />

74 HALI ISSUE 157<br />

Photo by Don Tuttle<br />

parallels. The two little yellow ‘houses’ in the blue areas between<br />

the minarets are typical design elements <strong>of</strong> the west <strong>Anatolian</strong><br />

‘Transylvanian’ workshop genre. The yellow-ground border is<br />

simple; an undulating red line snaking between quartered rectangles.<br />

While it is unusual, a number <strong>of</strong> comparisons are known. 31<br />

A 19th century <strong>prayer</strong> rug 8, and a very closely similar relative<br />

sold at Lefevre & Partners in London in 1976, 32 belong to a small<br />

family <strong>of</strong> <strong>rugs</strong> woven by Greek and Caucasian settlers in the westcentral<br />

<strong>Anatolian</strong> towns <strong>of</strong> Mihalıççık, Seyitgazi and Afyon, as<br />

defined in 1986 by Georg Butterweck and Dieter Orasch, 33 who<br />

propose that the hooked, stepped mihrab, common to all the<br />

<strong>rugs</strong> in the group, may have been intended to represent the<br />

spires <strong>of</strong> a Gothic cathedral. Some <strong>of</strong> the <strong>rugs</strong> in the group have<br />

been attributed to Konya in auction catalogues 34 and in the rug<br />

literature, 35 but the weave, handle and palette <strong>of</strong> the present<br />

rug is quite atypical <strong>of</strong> Konya. Both it and the Lefevre rug differ<br />

markedly from the others in featuring a central tree-<strong>of</strong>-life and<br />

in having bold, scalloped cartouches containing hooked forms<br />

superimposed on the borders. 36 Two other examples have similar<br />

wide multi-striped borders without cartouches. 37<br />

7<br />

Photo by Don Tuttle<br />

The central <strong>Anatolian</strong> town <strong>of</strong> Aksaray lies between Karapınar<br />

to the south and Kirs¸ehir to the north, with Nevs¸ehir and Nig˘de<br />

to the east. According to Iten-Maritz, 38 Aksaray was a centre for<br />

<strong>pile</strong> carpet-making during the Seljuk period, but carpet weaving<br />

there fell into steep decline during the 18th and 19th centuries.<br />

The town is now best known for kilims, sometimes attributed<br />

to Obruk, with repeat patterns <strong>of</strong> large geometric or hooked<br />

motifs on ivory grounds. 39<br />

The dotted white ground found on a very unusual Aksaray<br />

rug 9 is traditionally said to depict an animal skin. 40 The nine<br />

geometric motifs may represent splayed animal forms, perhaps<br />

modelled after an image <strong>of</strong> a single large pelt such as the wellknown<br />

17th century Konya rug in the TIEM, from the S¸ eyh Baba<br />

Yusuf Mosque in Sivrihisar-Eskis¸ehir. 41 A similar motif, <strong>pile</strong>d in<br />

green within an ivory medallion, appears on an ‘early’ red-ground<br />

Konya fragment (probably 18th century), recently advertised by<br />

Ziya Bozog˘lu <strong>of</strong> Perugia. 42 The rug’s relationship to Konya weavings<br />

is evident in its border design. 43 The general field layout is evocative<br />

<strong>of</strong> the TIEM’s 16th century white-ground Ushak lattice-design<br />

rug with ovoid ‘medallions’ at the interstices, which was also<br />

collected from the S¸ eyh Baba Yusuf Mosque, 44 and <strong>of</strong> a yellowground<br />

rug with stylised star motifs exhibited in Munich in 1984<br />

by Eberhart and Ulrike Herrmann. 45<br />

Previously unpublished, an 18th century east <strong>Anatolian</strong> <strong>village</strong><br />

rug 10 was seen in ‘Heavenly Gardens’ a one-man show <strong>of</strong> a small<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the Dixon Collection held in November 2002 in Walnut<br />

Creek, California. Related by design to the extended group <strong>of</strong> <strong>rugs</strong><br />

that Joseph McMullan called ‘Holbein variants’ on account <strong>of</strong> their<br />

strong relationship to earlier <strong>rugs</strong> <strong>of</strong> Seljuk origin, 46 its yellowground<br />

border is a simplified stylisation <strong>of</strong> Kufic script. A minority<br />

<strong>of</strong> these Holbein variant <strong>rugs</strong> have the perfectly formed ‘Seljuk<br />

star’ seen here at the centre <strong>of</strong> their elaborate medallions. 47<br />

It is interesting to compare this enigmatic rug to a 16th-17th<br />

century example in the Vakıflar Museum, Istanbul, 48 attributed to<br />

eastern Anatolia, which has similar box-like motifs (they also<br />

appear in various Caucasian <strong>rugs</strong>), surrounding its medallion.<br />

Another valid comparison is to a 16th-17th century yellow-ground<br />

medallion rug with Holbein-type motifs and small Seljuk stars<br />

in the field, recently published by Moshe Tabibnia <strong>of</strong> Milan. 49<br />

Jim Dixon suggests that his rug’s unusual palette and structural<br />

characteristics – black ground, natural black warps and wefts,<br />

and a relatively low density <strong>of</strong> about eighty knots per square<br />

8<br />

Photo by Don Tuttle<br />

8 West-central<br />

<strong>Anatolian</strong> <strong>prayer</strong> rug,<br />

19th century. 1.02 x<br />

1.22m (3'4" x 4'0").<br />

Ralph & Linda Kaffel<br />

Collection, Piedmont,<br />

California<br />

9 Aksaray rug,<br />

central Anatolia,<br />

before 1800. 1.07 x<br />

1.27m (3'6" x 4'2").<br />

Ralph & Linda Kaffel<br />

Collection, Piedmont,<br />

California<br />

10 East <strong>Anatolian</strong><br />

<strong>village</strong> rug, 18th<br />

century. 1.35 x<br />

1.70m (4'5" x 5'7").<br />

Jim Dixon Collection,<br />

Occidental, California<br />

Photo by Don Tuttle<br />

ANATOLIAN RUGS<br />

9<br />

HALI ISSUE 157 75<br />

10

Photo by Don Tuttle<br />

ANATOLIAN RUGS<br />

Photo by Dennis Anderson<br />

76 HALI ISSUE 157<br />

12<br />

11 Konya rug fragment,<br />

central Anatolia,<br />

early 19th century.<br />

1.02 x 1.73m (3'4" x<br />

5'8"). Ralph & Linda<br />

Kaffel Collection,<br />

Piedmont, California<br />

12 East <strong>Anatolian</strong><br />

<strong>prayer</strong> rug, 19th century.<br />

1.02 x 1.03m<br />

(3'4" x 3'41 ⁄2"). Ralph &<br />

Linda Kaffel Collection,<br />

Piedmont, California<br />

13 East or central<br />

<strong>Anatolian</strong> carpet<br />

fragment, 18th/19th<br />

century. 0.89 x 2.21m<br />

(2'11" x 7'3").<br />

Marshall & Marilyn<br />

R. Wolf Collection,<br />

New York<br />

11<br />

inch – may suggest an origin as far east as Erzurum. It is quite<br />

similar in its overall palette to another black-ground rug, attributed<br />

to <strong>Anatolian</strong> Kurds, <strong>of</strong>fered at auction in Germany in 2004. 50<br />

The Turkish term saz, according to Peter Stone, means “reed,<br />

bulrush or enchanted forest”, and defines an Ottoman floral design<br />

<strong>of</strong> leaves, rosettes and palmettes. 51 In the carpet and textile trade<br />

the term has acquired a more specific meaning, being applied to<br />

stylised serrated leaves, most <strong>of</strong>ten placed on a diagonal bias in<br />

the pattern. When an early 19th century Konya fragment 11,<br />

now in my own collection, was reviewed in HALI’s Auction Price<br />

Guide in 1997, 52 it was pointed out that saz leaves are familiar on<br />

Mujur and Karapınar <strong>rugs</strong>, and on yastıks from various parts <strong>of</strong><br />

Anatolia, 53 but that they are all but unknown in Konya <strong>village</strong><br />

<strong>rugs</strong>. I know <strong>of</strong> only one other example, sold twice at Sotheby’s<br />

in New York. 54 The border <strong>of</strong> stylised cartouche motifs, here<br />

repeated in the medallions, is best known from a number <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Anatolian</strong> coupled-column <strong>prayer</strong> <strong>rugs</strong>. 55 Werner Brüggemann<br />

and Harald Böhmer published three drawings to illustrate the<br />

evolution <strong>of</strong> this design. If we follow their reasoning, the border<br />

here is an 18th century variant. 56 The rug is reduced and<br />

represents about two-thirds <strong>of</strong> its original length, enough to<br />

13<br />

preserve its design integrity.<br />

I know <strong>of</strong> no close analogies among <strong>pile</strong>d <strong>prayer</strong> <strong>rugs</strong> to a 19th<br />

century east <strong>Anatolian</strong> weaving from my own collection 12. Its<br />

closest counterparts are three Reyhanlı <strong>prayer</strong> kilims with similar<br />

mihrabs and virtually identical multi-striped border systems. One<br />

was published by Yanni Petsopoulos in 1979, 57 a second, now with<br />

Dr Albert Mazzie in San Francisco, was published the same year<br />

by Alan Marcuson in the slender booklet that accompanied an<br />

exhibition at the Douglas Hyde Gallery in Dublin, Ireland, 58 and<br />

the third was posted online in January 2002 by Dr Mark Berkovich<br />

<strong>of</strong> Marvadim Gallery in Israel. The similarity <strong>of</strong> this <strong>prayer</strong> rug<br />

to the kilims suggests that it may have been woven in southeastern<br />

Turkey, in or around Reyhanlı, which is near Gaziantep and the<br />

border <strong>of</strong> Kurdish Anatolia, an area not well known for its <strong>pile</strong><br />

weaving. The rug was exhibited at Fort Mason during the 1990<br />

San Francisco ICOC, catalogued thus by Murray Eiland: “<strong>This</strong> is the<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> rug that defies labels, as its ivory warps would not seem<br />

congruent with the field design and colors, both <strong>of</strong> which suggest<br />

eastern <strong>Anatolian</strong> Kurdish work. The tightly packed knotting<br />

allows virtually no weft to be seen from the back <strong>of</strong> the rug, and<br />

the texture is most unusual.” 59<br />

A ‘unique’ central or eastern <strong>Anatolian</strong> fragment 13 from the<br />

Marshall and Marilyn R. Wolf Collection in New York was exhibited<br />

at the Textile Museum in Washington in 2002, and was<br />

published in Walter Denny’s accompanying catalogue. 60 Its palette<br />

argues for an east rather than central <strong>Anatolian</strong> attribution, and it<br />

could easily be dated to the 18th century. I know <strong>of</strong> no comparable<br />

examples, but a smaller fragment, probably from the same<br />

rug, was <strong>of</strong>fered at auction in Milan in November 2005. 61 Denny<br />

wrote that the four-pointed medallions are stylised descendants<br />

<strong>of</strong> earlier quatrefoil motifs; however the scalloped shape <strong>of</strong> the<br />

cruciforms may well relate to the crosses seen in Armenian <strong>rugs</strong>. 62<br />

These motifs, as well as the palette <strong>of</strong> the Wolf fragment, are<br />

very similar to those <strong>of</strong> a Surahani carpet published by Volkmar<br />

Gantzhorn. 63 Denny also remarks that the pendant motifs represent<br />

either <strong>Anatolian</strong> silver jewellery or mosque lamps, but they are<br />

surely the latter, as jewellery is usually represented by tasseled<br />

triangles, seen used as filler motifs in field 64 or elem 65 designs.<br />

Depictions <strong>of</strong> mosque lamps are, not surprisingly, less common<br />

in secular pieces, 66 than in <strong>prayer</strong> <strong>rugs</strong>. 67 A closely similar rendering<br />

<strong>of</strong> the lamp motif can be seen in the well-known 15th<br />

century ‘re-entrant’ <strong>prayer</strong> rug in the Topkapı Saray, Istanbul. 68<br />

The recently opened Vakıflar Museum in Ankara has substantial<br />

holdings <strong>of</strong> excellent 18th and 19th century <strong>Anatolian</strong> <strong>village</strong><br />

<strong>rugs</strong>, including several very unusual Melas weavings. 69 Of these,<br />

the <strong>prayer</strong> rug illustrated here 14 is perhaps the most unusual. I<br />

have over 2,000 images <strong>of</strong> Melas <strong>rugs</strong> in my photograph index and<br />

can find nothing close to this <strong>prayer</strong> rug, which has a coral red<br />

field on which a blossoming blue tree-<strong>of</strong>-life topped by a small<br />

ivory pentagon representing a <strong>prayer</strong> niche is superimposed.<br />

Perhaps the closest is an example <strong>of</strong>fered in London in 1976 by<br />

Lefevre, 70 which also features a tree and has a light yellow-ground<br />

border decorated with urn-like reciprocal motifs identical to those<br />

in the ivory-ground border <strong>of</strong> the Ankara rug. These motifs, while<br />

rare, are used in the borders <strong>of</strong> ‘Medjedeh’ <strong>prayer</strong> <strong>rugs</strong>, <strong>of</strong> which<br />

at least four examples are known. 71<br />

A lovely 19th century central <strong>Anatolian</strong> yastık 15, which at<br />

the time belonged to Corban LePell, was included in the ‘Passages’<br />

exhibition during the 5th ACOR in Burlingame, California in 2000.<br />

In the exhibition notes it was described as having “a rare design<br />

composed <strong>of</strong> two red and one blue rectangles, containing central<br />

eight-pointed stars surrounded by small angular motifs <strong>pile</strong>d in<br />

white, green, blue, light red and aubergine, framed by an ‘hourglass’<br />

design border.” <strong>This</strong> ‘hourglass’ or ‘double-M’ motif may<br />

<strong>of</strong>fer a clue to its origin, as an identical border appears on four<br />

central <strong>Anatolian</strong> yastıks published by Morehouse, 72 on a central<br />

<strong>Anatolian</strong> ‘pomegranate tree’ yastık recently sold at Grogan’s in<br />

Massachusetts, 73 and on a yastık sold at Skinner in Boston. 74 While<br />

this exact border seems to be exclusive to yastıks, stylised versions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the motif do appear on a handful <strong>of</strong> central <strong>Anatolian</strong> <strong>rugs</strong>. 75<br />

The field design <strong>of</strong> three rectangles appears to have more in<br />

common with Caucasian rather than <strong>Anatolian</strong> <strong>rugs</strong>. 76 While<br />

there are no close analogies among published yastıks, a somewhat<br />

related example attributed to eastern Anatolia, with its<br />

field divided into one blue and one red dotted rectangle, was<br />

exhibited at the conference hotel during the 2007 Istanbul ICOC. 77<br />

Even though it has a red ground, a whimsical central <strong>Anatolian</strong><br />

mat 16 was included in my 2003 article on yellow-ground Konya<br />

<strong>rugs</strong>. At the time I wrote: “I would place it in the group for its<br />

palette, all-over pattern <strong>of</strong> cruciforms and other odd shapes, naïve<br />

border, wool and weave characteristics”. 78 Its function is not<br />

obvious, as its almost square format and the lack <strong>of</strong> end panels<br />

argue against it being a pillow cover. The cross-like motifs are<br />

formed by squares with vertical and horizontal projections and<br />

most probably owe their origin to very similar elements, which<br />

Carl Johann Lamm describes as a “design <strong>of</strong> square cartouches<br />

in alternate rows”, seen on a 15th century brown-ground fragment<br />

found at Fostat in Egypt. 79 Our weaver clearly had difficulty<br />

executing the pattern with any precision, as well as problems<br />

with the border, but it is such imperfections that brand it as<br />

‘unique’ and add to its charm.<br />

Discussing the only yastık published in his landmark Islamic<br />

Carpets, Joseph McMullan wrote: “Occasionally a small Turkish<br />

mat is found which contains an extraordinary amount <strong>of</strong> power<br />

within a very small space.” 80 Of very different design, a 19th<br />

century west <strong>Anatolian</strong> yastık 17 from the Wendel and Diane<br />

Swan Collection is another such. 81 It is rare but not unique; a<br />

squarer but otherwise almost identical piece was exhibited by<br />

Raymond Benardout in Los Angeles during the Santa Monica<br />

ACOR in 1996. In his Woven Stars catalogue, Benardout remarked<br />

that it was “… a very unusual yastık from Oushak. I have no awareness<br />

<strong>of</strong> encountering in my dealings such an interesting mat.” 82<br />

Both yastıks owe their design to 16th/17th century <strong>Anatolian</strong><br />

<strong>village</strong> <strong>rugs</strong> with large, elaborate central medallions, 83 while their<br />

distinctive palette also occurs on an 18th century Aksaray rug<br />

<strong>of</strong>fered at auctuon in Germany in 2004. 84 Morehouse published<br />

a related yastık with a less elaborate central medallion. 85<br />

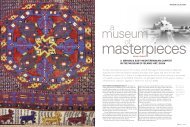

A well-known 17th century Konya <strong>prayer</strong> rug, without recorded<br />

parallel in the literature 18, serves as an appropriate terminus for<br />

this personal survey. On exhibition in the Ibrahim Pas¸a Saray<br />

during ICOC XI in Istanbul in 2007, 86 it is, in the words <strong>of</strong> Nazan<br />

ANATOLIAN RUGS<br />

14<br />

14 Melas <strong>prayer</strong> rug,<br />

southwest Anatolia,<br />

19th century. 1.19 x<br />

1.36m (3'11" x 4'6").<br />

Vakıflar Museum,<br />

Ankara<br />

HALI ISSUE 157 77

ANATOLIAN RUGS<br />

78 HALI ISSUE 157<br />

16<br />

15<br />

15 Konya (?) yastık,<br />

central Anatolia, 19th<br />

century. 0.46 x 0.91m<br />

(1'6" x 3'0"). Private<br />

collection, courtesy<br />

Corban LePell,<br />

Hayward, California<br />

16 Konya mat,<br />

central Anatolia, circa<br />

1800. 0.61 x 0.66m<br />

(2'0" x 2'2"). Ralph &<br />

Linda Kaffel<br />

Collection, Piedmont,<br />

California<br />

17 Ushak (?) yastık,<br />

west Anatolia, 19th<br />

century. 0.56 x 0.86m<br />

(1'10" x 2'10").<br />

Wendel & Diane<br />

Swan Collection,<br />

Alexandria, Virginia<br />

Ölçer and Walter Denny “… among the finest treasures from the<br />

vast collection <strong>of</strong> <strong>prayer</strong> <strong>rugs</strong> in the T.I.E.M.” They tentatively<br />

assign it to Konya and the 18th century and propose that the<br />

unusual elaborate shape <strong>of</strong> its <strong>prayer</strong> niche is “suggestive <strong>of</strong> the<br />

three dimensional muqarnas forms commonly found in niche areas<br />

above the doorways and mihrabs in Ottoman buildings and<br />

those <strong>of</strong> their Seljuk predecessors in Anatolia.” 87<br />

However, there is little agreement among the authors <strong>of</strong> the<br />

various publications in which this rug appears regarding its age<br />

or origin. In the recent Istanbul ICOC catalogue, it is dated to<br />

the 17th century and attributed unambiguously to Konya, with<br />

its provenance given as “from Sultan Alaaddin Keykubat Tomb in<br />

Konya”. 88 The authors <strong>of</strong> the Turkish Ministry <strong>of</strong> Culture’s Turkish<br />

Handwoven Carpets also date it to the 17th century, attribute it to<br />

Kula, and rather fancifully suggest that its elaborate, denselypacked<br />

floral border represents the Garden <strong>of</strong> Eden. 89 Although the<br />

floral border is untypical <strong>of</strong> Konya weavings, there is a precedent<br />

in a 16th century ‘re-entrant’ <strong>prayer</strong> rug with a related border,<br />

tentatively attributed to Konya, in the Orient Stars Collection. 90<br />

Plain ivory- or camel-coloured mihrabs, rare in most types <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>prayer</strong> <strong>rugs</strong>, consistently appear in the 17th and 18th century<br />

‘Transylvanian’ genre. 91 Stefano Ionescu has published at least 22<br />

such <strong>rugs</strong>, variously attributed to west <strong>Anatolian</strong> weaving centres<br />

such as Ushak and Melas. 92<br />

Turkey is full <strong>of</strong> surprises. While some dealers and collectors<br />

bemoan that the market has been ‘picked over’, rare and even<br />

‘unique’ pieces continue to emerge. Perhaps this modest survey,<br />

subjective as it is, might inspire others to share more <strong>of</strong> their<br />

unknown treasures with us. In any case, sincere gratitude is due<br />

to the private collectors whose generous co-operation has made<br />

this article possible. I am deeply saddened that the late Charles<br />

Lave is not here to see his ‘Devil’s rug’ grace the pages <strong>of</strong> HALI.<br />

17<br />

18 Konya <strong>prayer</strong> rug,<br />

central Anatolia,<br />

17th century. 1.09 x<br />

1.78m (3'7" x 5'10").<br />

Collected from the<br />

tomb <strong>of</strong> Sultan Alaaddin<br />

Keykubat in<br />

Konya, Türk ve Islam<br />

Eserleri Museum,<br />

Istanbul, no.354<br />

ANATOLIAN RUGS<br />

HALI ISSUE 157 79<br />

18

ANATOLIAN RUGS<br />

80 HALI ISSUE 157<br />

NOTES<br />

1 Lawrence Kearney, ‘A Kind <strong>of</strong><br />

Meta-Art, Caucasian Rugs from<br />

the Rudnick Collection’, HALI 152,<br />

2007, pp.62-71.<br />

2 Five can be assigned to the 18th<br />

century, twelve to the 19th.<br />

3 Alberto Levi, Antique Textile Art<br />

1, Milan 2000, pl.1<br />

4 HALI 82, 1995, p.111.<br />

5 Cathryn M. Cootner, <strong>Anatolian</strong><br />

Kilims – The Caroline and H.<br />

McCoy Jones Collection, San<br />

Francisco 1990, pls.6, 13, 17;<br />

Volkmar Enderlein, Orientalische<br />

Kelims, Berlin 1986, pp.60/61; Jack<br />

Cassin, Image Idol Symbol,<br />

Ancient <strong>Anatolian</strong> Kelims, New<br />

York 1989, pl.6; Jürg Rageth, in<br />

E.Heinrich Kirchheim<br />

et al., Orient Stars, A Carpet Collection,<br />

Stuttgart 1993, writes <strong>of</strong><br />

pl.145, a yellow-ground runner<br />

fragment with stepped motifs,<br />

“this is an excellent example <strong>of</strong><br />

the interrelationship between<br />

kilims and carpet designs”.<br />

6 Ibid., pl.4.<br />

7 HALI 121, 2002, p.49.<br />

8 Brian Morehouse,Yastiks: Cushion<br />

Covers and Storage Bags <strong>of</strong> Anatolia,<br />

Philadelphia 1996, p.94, pl.82<br />

(1'11" x 2'8").<br />

9 Ibid, pl.83.<br />

10 Ayan Gülgönen, Konya Cappadocia<br />

Carpets from the 17th to the<br />

19th Centuries, Istanbul 1997,<br />

pl. 58 (3'4" x 10'2").<br />

11 Murray L. Eiland Jr., ‘Oriental<br />

Rugs in Occidental’, HALI 109,<br />

2000, p.104 = Skinner, Bolton<br />

MA, 6 December 1987, lot 110.<br />

12 Peter E. Saunders, Tribal Visions,<br />

Marin 1980, pl.56.<br />

13 Peter Bausback, Alte und Antike<br />

Orientalische Knüpfkunst, Mannheim<br />

1983, p.13.<br />

14 Christopher Alexander, A Foreshadowing<br />

<strong>of</strong> 21st Century Art.<br />

The Color and Geometry <strong>of</strong> Very<br />

Early Turkish Carpets, New York<br />

1993, p.192 (a “waving border<br />

carpet”); Eduardo Concaro &<br />

Alberto Levi, eds., Sovrani Tappeti,<br />

Milan 1999, pl.23 = HALI 55,<br />

1991, p.63 = HALI 96, p. 61.<br />

15 TIEM no.395; Robert Pinner &<br />

Walter B. Denny, eds., Oriental<br />

Carpet & Textile Studies II:<br />

Carpets <strong>of</strong> the Mediterranean<br />

Countries 1400-1600, London<br />

1986, p.5 = Oktay Aslanapa, One<br />

Thousand Years <strong>of</strong> Turkish<br />

Carpets, Istanbul 1988, fig.119 =<br />

Nazan Ölçer et al., Turkish Carpets<br />

from the 13th-18th Centuries,<br />

Istanbul 1996, pl.145 = HALI 88,<br />

1996, p.99 = HALI 152, 2007,<br />

p.100.<br />

16 Ulrich Schürmann, Oriental<br />

Carpets, London 1966, p.102 =<br />

Michael Franses, An Introduction<br />

to the World <strong>of</strong> Rugs, London<br />

1973, pl.8; Anton Danker, Meisterstucke<br />

Orientalischer Knüpfkunst:<br />

Sammlung Anton Danker, Wiesbaden<br />

1966, pl.13; Sotheby’s,<br />

London, 9 January 1981, lot 159.<br />

17 Hülye Tezcan & Sumiyo<br />

Okumura, eds., The Weaving<br />

Heritage <strong>of</strong> Anatolia 1, Istanbul<br />

2007, p.156, pl.16.<br />

18 Schürmann 1966, op.cit.,<br />

pp.74/5 = Rippon Boswell,<br />

Wiesbaden, 19 November 2005,<br />

lot 91 = HALI 145, 2006, p.116.<br />

19 Grogan, Dedham MA, 22 April<br />

2006, lot 115; HALI 88, 1996,<br />

p.117; Tezcan & Okumura, op.cit.,<br />

pl.34, Simsek Collection.<br />

20 Concaro & Levi, op.cit., pl.42;<br />

Christie’s, London, 28 April 2004,<br />

lot 99; HALI 41, 1988, ad.p.78;<br />

Leone Mesciulam & Louisa<br />

Belleri, Tappeti Anatolici dal ‘600 al<br />

‘900, Genoa 1981, pl.12.<br />

21 Peter F. Stone prefers ‘Rhodian<br />

lilies’, see Tribal and Village Rugs –<br />

The Definitive Guide to Design,<br />

Pattern and Motif, London 2004,<br />

pp.74-5, border A72.<br />

22 Trefoil, Guls, Stars & Gardens,<br />

Oakland 1990, pl.XIII = HALI 87,<br />

1996, p.106. Unconnected to the<br />

San Francisco ICOC later the same<br />

year, the ‘Trefoil’ exhibition featured<br />

pieces from the collections <strong>of</strong><br />

Gilbert & Hillary Dumas, Jim<br />

Dixon and John Webb Hill.<br />

23 HALI 123, 2002, p.82.<br />

24 A very similar ‘star’ appears in:<br />

the octagons on a 16th century<br />

‘Holbein’ carpet in Berlin,<br />

no.79,110; see Friedrich Spuhler,<br />

Oriental Carpets in the Museum<br />

<strong>of</strong> Islamic Art, Berlin, Munich<br />

1988, pl.5; in the border <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Beyshehir Seljuk carpet in the<br />

Mevlana Museum, Konya, see<br />

Aslanapa, op.cit., p.25, pl.11; see<br />

also a rug in the Textile Museum<br />

(TM R34.2.1), in Ralph S. Yohe &<br />

H. McCoy Jones, Turkish Rugs,<br />

Washington 1968, pl.15.<br />

25 Morehouse, op.cit., pl.7,<br />

attributed to west Anatolia, and<br />

Lefevre, London, 25 May 1984, lot<br />

16, attributed to Mujur.<br />

26 HALI 45, 1989, ad.p.11, attributed<br />

to west but almost certainly<br />

east Anatolia, mid-19th century;<br />

Werner Brüggemann & Harald<br />

Böhmer, Rugs <strong>of</strong> the Peasants<br />

and Nomads <strong>of</strong> Anatolia, Munich<br />

1983, pl.105, east Anatolia (with a<br />

dotted abrashed field similar to the<br />

present rug, and with a related<br />

border); J.M. Sorkin brochure,<br />

Philadelphia July 1997; Murray L.<br />

Eiland, Jr., Oriental Rugs: A<br />

Comprehensive Guide, Greenwich<br />

CT 1973, p.119, fig.100, an early<br />

20th century quite ‘touristy’<br />

looking Turkish ‘Kazak’ from Kars;<br />

Ministry <strong>of</strong> Culture & Tourism,<br />

Turkish Handwoven Carpets,<br />

Catalog No.2, Ankara 1988,<br />

no.0184, Maltaya; ibid., Catalog<br />

No.4, no.0384, Elazi˘g.<br />

27 Gerard Paquin, personal correspondence.<br />

He writes: “They are<br />

crudely and variously drawn here,<br />

but in the upper part <strong>of</strong> the field<br />

they have the dot at the edge <strong>of</strong> the<br />

ball as Çintamani traditionally do”.<br />

28 Franz Sailer, Textile Fragments,<br />

Salzburg 1988, p.28, Konya, 18th<br />

century = HALI 40, 1988, p.93 =<br />

HALI 49, 1990, p.9; HALI 87,<br />

1996, p.37, Konya, 18th century or<br />

earlier; Eberhart Herrmann, Seltene<br />

Orientteppiche IX, Munich 1987,<br />

no.8, Konya 18th century;<br />

Kirchheim et al., op.cit., pl.116,<br />

Konya, 17th/18th century; Georg<br />

Butterweck et al., Antique<br />

<strong>Anatolian</strong> Carpets from Austrian<br />

Collections, Vienna 1983, pl.42,<br />

Konya, circa 1800; Wilfried<br />

Stanzer et al., Antique Oriental<br />

Carpets from Austrian Collections,<br />

Vienna 1986, east Anatolia, 19th<br />

century; HALI 71, 1993, p.144,<br />

Konya, 19th century; HALI 137,<br />

2004, p.68, Jon Anderson Collection,<br />

central Anatolia, 19th century;<br />

Georg Butterweck & Dieter Orasch,<br />

Handbook <strong>of</strong> <strong>Anatolian</strong> Carpets;<br />

Central Anatolia, Vienna 1986,<br />

pl.67, a panel on a Obruk rug, in<br />

which they suggest that the motif<br />

represents a stylised St Andrew’s<br />

cross.<br />

29 HALI 156, 2008, p.27.<br />

30 Kirchheim et al., pl.141, a fragment<br />

<strong>of</strong> a 17th/18th century<br />

Konya rug with amulet motifs<br />

which may bear a relationship to<br />

the present motif.<br />

31 The closest parallel is an inner<br />

border on a Manastir <strong>prayer</strong> rug in<br />

Rainer Kreissl, Gates to Heaven:<br />

Anatolia, Munich 1998, pl.19, with<br />

a blue line on a yellow ground<br />

meandering through various filler<br />

motifs. Kirchheim et al., op.cit.,<br />

pl.141 has a meandering red line<br />

on a yellow ground.<br />

32 Lefevre, London, 6 February<br />

1976, lot 17.<br />

33 Butterweck & Orasch, op,cit.,<br />

pp.114-116, pls.209-217.<br />

34 Jean Lefevre attributed his rug<br />

to Konya, mid-19th century;<br />

Christie’s, London, 13 June 1983,<br />

lot 14 = Christie’s New York, 12<br />

December 2007, lot 31.<br />

35 Helmut Reinisch, Von Bagdad<br />

nach Stamboul, Graz 1983, pl.36 =<br />

HALI 41, 1998, p.101.<br />

36 A related tree-<strong>of</strong>-life rug <strong>of</strong><br />

much later vintage, is attributed to<br />

Mihalıççık by Kurt Zipper &<br />

Claudia Fritsche, Oriental Rugs<br />

Volume 4, Turkish, Woodbridge<br />

1989, p.165, but to Altintas¸ by<br />

Butterweck & Orasch, op.cit.,<br />

pl.224.<br />

37 Ibid., pls.214-5.<br />

38 J. Iten-Maritz, Turkish Carpets,<br />

Tokyo 1977, p.36.<br />

39 Yanni Petsopoulos, Kilims: Flatwoven<br />

Tapestry Rugs, New York<br />

1979, pls.171-2.<br />

40 HALI 4/4, 1982, p.372;<br />

Christie’s, New York, 16 June<br />

2003, lot 103 = HALI 128, 2003,<br />

p.124; Ministry <strong>of</strong> Culture, op.cit.,<br />

Catalog No.1, 1987, no.0034;<br />

Lefevre, London, 17 February<br />

1984, lot 10.<br />

41 Ölçer et al., op.cit., pl.146; HALI<br />

112, 2000, cover.<br />

42 HALI 153, 2007, p.122.<br />

43 Christie’s, New York, 8<br />

February 1992, lot 35; HALI 70,<br />

1993, p.31; Sotheby’s, London, 19<br />

October 1994, lot 91; Sotheby’s,<br />

New York, 13 December 1996,<br />

lot 54.<br />

44 TIEM no.712; HALI 91, 1997,<br />

cover = Ölçer et al., op.cit., pl.114<br />

= Pinner & Denny, op.cit., p.4, fig.2.<br />

45 Ebertart Herrmann, Seltene Orientteppiche<br />

VI, Munich 1984, pl.15.<br />

46 Joseph V. McMullan, Islamic<br />

Carpets, New York 1965, pl.36.<br />

Also called a ‘Ghirlandaio’ rug<br />

after the depiction <strong>of</strong> a similar<br />

central motif by the 15th century<br />

artist Domenico Ghirlandaio.<br />

McMullan’s rug has a central<br />

Memling-gül, with ‘Seljuk’ stars in<br />

the corners. Other single<br />

medallion examples lacking the<br />

central ‘Seljuk’ star include:<br />

Eberhart Herrmann, Seltene Orientteppiche<br />

X, Munich 1988, pl.13;<br />

Concaro & Levi, op.cit., pl.27;<br />

William.T. Price, Divine Images<br />

and Magic Carpets, Amarillo 1987,<br />

pl.33; Rippon Boswell,<br />

Wiesbaden, 25 May 1998, lot 137;<br />

Christie’s, New York, 8 February<br />

1992, lot 108 (Meyer-Müller<br />

Collection); Robert De Calatchi,<br />

Oriental Carpets, Rutland VT 1967,<br />

p.12; Alberto Levi, Antique Textile<br />

Art 4, Milan 2004, pl.1. Another<br />

McMullan rug, op.cit.., pl.97, has a<br />

central ‘Solomon’ star and corner<br />

spandrels, as does Rainer Kreissl,<br />

Art as Tradition– Anatolia, Prague<br />

1995, pl.72.<br />

47 Werner Grote-Hasenbalg, Der<br />

Orientteppich: seine Geschiichte<br />

und seine Kultur, Berlin 1922, p.88,<br />

fig.51, a 16th century rug with a<br />

highly stylised central star. Also<br />

Alexander, op.cit., p.315 = Jean<br />

Lefevre, Turkish Carpets, London<br />

1977, no.16; Lefevre, London, 28<br />

September 1973, lot 6; Lefevre,<br />

London, 25 March 1977, lot 31.<br />

48 Belkıs Balpinar & Udo Hirsch,<br />

Carpets <strong>of</strong> the Vakıflar Museum,<br />

Istanbul, Wesel 1988, pl.30.<br />

49 Jon Thompson, Milestones in<br />

the History <strong>of</strong> Carpets, Milan 2007,<br />

pl.4 = HALI 152, 2007, p.141.<br />

50 Rippon Boswell, Wiesbaden,<br />

20 November 2004, lot 147.<br />

51 Peter F. Stone Oriental Rug<br />

Lexicon, London 1997, p.199.<br />

52 HALI 91, 1997, p.154 = Sotheby’s<br />

New York, 13 December<br />

1996, lot 36.<br />

53 Morehouse, op.cit., illustrates<br />

two from west Anatolia (nos.41,<br />

42), six from central Anatolia<br />

(no.60, possibly Karapınar; no.64,<br />

Ni˘gde/Gelveri; nos.69-72, Mujur)<br />

and one from east Anatolia<br />

(no.133).<br />

54 A more formally drawn yellowground<br />

Konya rug, attributed to<br />

the mid-19th century, Sotheby’s,<br />

New York on 14 December 2001,<br />

lot 59 and again on 2 December<br />

2003, lot 24. The comparison<br />

cited in the 2003 catalogue as a<br />

“red-ground Konya rug”, while<br />

related by design, is actually a<br />

central <strong>Anatolian</strong> yastık, advertised<br />

by Thomas Caruso in HALI 98,<br />

p.53. A white-ground rug with<br />

three pairs <strong>of</strong> saz leaves in the<br />

TIEM (no.310), collected in<br />

Sivrihisar, is <strong>of</strong> uncertain<br />

attribution: Nazan Ölçer & Walter<br />

B. Denny, <strong>Anatolian</strong> Carpets.<br />

Masterpieces from the Museum<br />

<strong>of</strong> Turkish and Islamic Arts<br />

Istanbul, Bern 1999, pl.84, assign<br />

it to central Anatolia, 18th/ 19th<br />

century, while it was dated to the<br />

17th/18th century in HALI 105,<br />

1999, p.95. There is only a slim<br />

chance that it was made in Konya.<br />

A more geometric version <strong>of</strong> a<br />

similar design was published by<br />

May H. Beattie, ‘Some Rugs <strong>of</strong><br />

the Konya Region’, Oriental Art,<br />

Spring 1976, p.71, fig.20.<br />

55 Central <strong>Anatolian</strong> ‘coupledcolumn’<br />

<strong>prayer</strong> <strong>rugs</strong> with this<br />

border include: Balpinar & Hirsch,<br />

op.cit., pl. 70 (Konya), Ministry <strong>of</strong><br />

Culture, op.cit., Catalog no.1, 1987,<br />

no.0060 and Catalog no.5, 1995,<br />

no.0572 (both Konya); a Konya-<br />

Ladik in Peter Bausback, Alte und<br />

Antike Orientalische Knüpfkunst,<br />

Mannheim 1982, p.11; and a Karapınar<br />

on the cover <strong>of</strong> Butterweck<br />

& Orasch, op.cit. An earlier, more<br />

refined version <strong>of</strong> the border can<br />

be seen on the Davanzati column<br />

Ladik, sold by Lefevre, London, on<br />

27 April 1979, lot 21, and on the<br />

famous Ballard Ottoman <strong>prayer</strong><br />

rug, in Richard Ettinghausen &<br />

Maurice Dimand, Prayer Rugs,<br />

Washington DC 1974, pl.XXI.<br />

56. Brüggemann & Böhmer,<br />

op.cit., p.106, flg.128 a, b, c.<br />

57 Petsopoulos, op.cit., pl.217.<br />

58 Alan Marcuson et al., Kilims –<br />

The Traditional Tapestries <strong>of</strong><br />

Turkey, Dublin 1979, no.10,<br />

described as a “9-border <strong>prayer</strong><br />

kilim – southeast Anatolia”.<br />

59 Murray L. Eiland Jr., Oriental<br />

Rugs from Paciflc Collections, San<br />

Francisco 1990, p.57, pl.28.<br />

60 Walter B. Denny, The Classical<br />

Tradition in <strong>Anatolian</strong> Carpets,<br />

Washington 2002, pl.43.<br />

61 Finarte, Milan, 9 November<br />

2005, lot 186, dated to the 16th/<br />

17th century (1'10" x 2'5").<br />

62 James M. Keshishian, Inscribed<br />

Armenian Rugs <strong>of</strong> Yesteryear,<br />

Washington DC 1994, pl.A153;<br />

Murray L. Eiland Jr.,<br />

Passages–Celebrating the Rites <strong>of</strong><br />

Passage in Inscribed Armenian<br />

Rugs, San Francisco 2002, pl.40.<br />

63 Volkmar Gantzhorn, The Christian<br />

Oriental Carpet, Cologne 1991,<br />

p.401, no.537.<br />

64 Concaro & Levi, op.cit., pl.83;<br />

Kirchheim et al., op.cit., pls.116,<br />

151.<br />

65 Nagel, Stuttgart, 5 November<br />

2002, lot 10; Dennis R. Dodds,<br />

Philadelphia, a zig-zag striped<br />

yatak posted on cloudband.com<br />

on 9 January 2003.<br />

66 Rippon Boswell, Wiesbaden,<br />

16 November 2002, lot 14, a<br />

yellow-ground Çal carpet with an<br />

all-over pattern <strong>of</strong> mosque lamps;<br />

Bergama and Dazkırı medallion<br />

carpets, e.g. Maurice S. Dimand,<br />

The Ballard Collection <strong>of</strong> Oriental<br />

Rugs in the City Art Museum, St<br />

Louis, St Louis 1935, pl.XXX, and<br />

Rippon Boswell, Wiesbaden, 16<br />

November 1996, lot 169.<br />

67 Numerous examples include:<br />

Bergama, Ministry <strong>of</strong> Culture,<br />

op.cit., Catalog No.1, 1987,<br />

no.0043; Alexander, op.cit., p.127;<br />

a ‘Bellini’ rug in Eberhart<br />

Herrmann, Asiatische Teppich und<br />

Textilkunst 4, Munich 1992, pl.4; a<br />

saf at the TIEM, in Gantzhorn,<br />

op.cit., p.505; Konya, Yohe &<br />

Jones, op.cit., p.24; E. Herrmann,<br />

Seltene Orientteppiche II, Munich<br />

1979, pl.14. The most realistic<br />

depictions <strong>of</strong> mosque lamps<br />

appear in a 16th century Ottoman<br />

rug, Denny 2002, op.cit., pl.44,<br />

and in safs, Ölçer & Denny,<br />

op.cit., pls.37-9.<br />

68 J.M.Rogers & Hülye Tezcan,<br />

The Topkapı Saray Museum,<br />

Carpets, London 1987, pl.4; HALI<br />

39, 1988, p.26 (55), HALI 58,<br />

1991, p.86.<br />

69 I am grateful to Patrick Weiler<br />

who visited Ankara after ICOC XI<br />

in 2007 and posted his photographs<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Vakıflar <strong>rugs</strong> on<br />

turkotek.com.<br />

70 Lefevre, London, 6 February<br />

1976, lot 28, mid-19th century<br />

(3’3” x 5’4”).<br />

71 Mesciulam & Belleri, op.cit.,<br />

pl.18; Rippon Boswell,<br />

Wiesbaden, 12 November 1994,<br />

lot 25; Brunk Auctions, Asheville<br />

NC, 31 May 2003, lot 63;<br />

Sotheby’s, New York, 17<br />

December 1999, lot 132.<br />

72 Morehouse, op.cit., pl.101 (main<br />

border), pls 102-4 (guard borders).<br />

73 Grogan, Dedham MA, 22 April<br />

2006, lot 115.<br />

74 Skinner, Bolton, 17 September<br />

1994, lot 143.<br />

75 Balpinar & Hirsch, op.cit., pl.66,<br />

a central <strong>Anatolian</strong> ‘shield’ carpet;<br />

Rippon Boswell, Wiesbaden, 11<br />

November 1993, lot 128; one half<br />

<strong>of</strong> the motif is used in the borders<br />

<strong>of</strong> some Karapınar <strong>rugs</strong>: Rippon<br />

Boswell, Wiesbaden, 20 May 1995,<br />

lot 79A = HALI 61, 1992, p.173 =<br />

Sotheby’s, London, 16 October<br />

2002, lot 45; Christie’s, London, 1<br />

May 2003, lot 158.<br />

76 HALI 109, 2000, p.106, fig.4, a<br />

Kazak rug in the Dixon Collection;<br />

Balpinar & Hirsch, op.cit., pl.81, an<br />

18th century south Caucasian rug.<br />

77 Tezcan & Okumura, op.cit.,<br />

pl.65, Simsek Collection.<br />

78 Ralph Kaffel, ‘Heart and Soul –<br />

The Yellow-Ground Rugs <strong>of</strong><br />

Konya’, HALI 128, 2003. pp.90-8.<br />

79 National Museum, Stockholm,<br />

no.NM 40/1936, 6" x 9". See Carl<br />

Johann Lamm, Carpet Fragments,<br />

The Marby Rug and some Fragments<br />

<strong>of</strong> Carpets found in Egypt,<br />

Stockholm 1985, pl.23 and p.30.<br />

80 McMullan, op.cit., p.338,<br />

pl.117.<br />

81 Tezcan & Okumura, op.cit.,<br />

p.145, no.6.<br />

82 Raymond Benardout, Woven<br />

Stars. Rugs and Textiles from<br />

Southern Californian Collections,<br />

Los Angeles 1996, p.74, pl.85. Its<br />

dimensions are given as 2'2"x<br />

2'7", but it appears to be smaller<br />

than the present piece.<br />

83 E.g. Kirchheim et al., op.cit.,<br />

pl.160, a 17th century central<br />

<strong>Anatolian</strong> <strong>village</strong> rug.<br />

84 Rippon Boswell, Wiesbaden,<br />

20 November 2004, lot 136.<br />

85 Morehouse, op.cit., pl.43.<br />

86 Ölçer & Denny, op.cit., pl.90.<br />

87 Ibid., pl.101 and p.61.<br />

88 Walter B. Denny et al.,<br />

Weaving Heritage <strong>of</strong> Anatolia 2,<br />

Istanbul 2007, p.170, pl.90.<br />

89 Ministry Of Culture, op.cit.,<br />

Catalog No.4, 1990, no.0313.<br />

90 HALI 58,1991, p.100; Kirchheim<br />

et al., op.cit., pl.189.<br />

91 Stanzer et al., op.cit., pl.11;<br />

Sotheby’s New York, 14<br />

December 2001, lot 50; Nathaniel<br />

Harris, Rugs and Carpets <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Orient, London 1977, p.61; HALI<br />

114, 2001, p.61; Eberhart<br />

Herrmann, Seltene Orientteppiche<br />

III, Munich 1980, pl.1; HALI 1/3,<br />

1978, p.275, flg.6; Emil<br />

Schmutzler, Altorientalische Teppiche<br />

in Siebenbürgen, Leipzig<br />

1933, pl.37; Angela Völker, Die<br />

Orientalischen Knüpfteppiche im<br />

MAK, Vienna 2001, pl.28, and a<br />

much-published Ushak in the TIEM,<br />

Denny et al., op.cit., pl.93 = Ölçer<br />

et al., op.cit., pl.144 = Ölçer &<br />

Denny, op.cit., pl.133 = Ministry<br />

<strong>of</strong> Culture, op.cit., Catalog No.5,<br />

1995, no.0560 = HALI 151, 2007,<br />

p.175.<br />

92 Stefano Ionescu, Antique<br />

<strong>Anatolian</strong> Rugs in Transylvania,<br />

Rome 2005, pls 149-52, 154-6,<br />

158, 160-2, 164-6, 168-73, 175-6.<br />

ANATOLIAN RUGS<br />

HALI ISSUE 157 81