Judicial Review & Law - Faculty of Law, The University of Hong Kong

Judicial Review & Law - Faculty of Law, The University of Hong Kong

Judicial Review & Law - Faculty of Law, The University of Hong Kong

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Judicial</strong> <strong>Review</strong> & <strong>Law</strong><br />

Benny Y. T. Tai<br />

Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor<br />

<strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong><br />

Learning Outcomes<br />

After attending this session, students should be<br />

able to:<br />

• illustrate the concept <strong>of</strong> jurisdiction<br />

• explain errors <strong>of</strong> law that may cause an<br />

administrative decision to be invalidated by the<br />

Court<br />

• analyze the application <strong>of</strong> the “Anisminic<br />

principles” in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong><br />

• apply principles <strong>of</strong> statutory interpretation<br />

1<br />

2<br />

Issues<br />

• What is a jurisdictional error?<br />

• What is an error <strong>of</strong> law?<br />

• Does every error <strong>of</strong> law go to jurisdiction?<br />

• What is the status <strong>of</strong> the “Anisminic<br />

principles” in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong>?<br />

• What are the principles <strong>of</strong> statutory<br />

interpretation?<br />

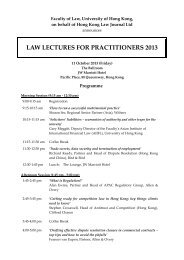

Propose((<br />

bill<br />

Legislative<br />

Council!<br />

Empower((<br />

&(delimit(<br />

Cons7tu7onal(<br />

(review<br />

Applica7on(for(<br />

judicial(review<br />

Market!<br />

Central<br />

Government!<br />

HKSAR<br />

Government!<br />

<strong>Judicial</strong>(<br />

review<br />

Judiciary!<br />

Civil Society;<br />

Media &<br />

General Public!<br />

Power(to(<br />

review?<br />

Procedural(<br />

and(<br />

substan7ve(<br />

decisions<br />

A governance<br />

problem!<br />

3<br />

4

ULTRA VIRES<br />

Grounds <strong>of</strong> <strong>Judicial</strong> <strong>Review</strong><br />

• Illegality<br />

• Irrationality<br />

• Procedural Impropriety<br />

5<br />

6<br />

Chief Justice Ge<strong>of</strong>frey Ma’s speech at<br />

Ceremonial Opening <strong>of</strong> the legal Year 2011<br />

“<strong>The</strong> judicial oath requires judges to look no further than<br />

the law as applied to the facts. <strong>The</strong> starting point and the<br />

end position in any case, is the law.<br />

This is the true role <strong>of</strong> the courts. <strong>The</strong> courts do not serve<br />

the people by solving political, social or economic<br />

issues. <strong>The</strong>y are neither qualified nor constitutionally able<br />

to do so. However, where legal issues are concerned, this is<br />

the business <strong>of</strong> the courts and whatever the context or the<br />

controversy, the courts and judges will deal with these<br />

legal issues.”<br />

<br />

7<br />

Issues that court will consider<br />

in <strong>Judicial</strong> <strong>Review</strong><br />

law<br />

as applied<br />

to the facts<br />

fairly<br />

8

4 steps (issues) in Exercising<br />

Administrative Powers<br />

procedures<br />

law<br />

fact (evidence)<br />

application<br />

<strong>The</strong> concept <strong>of</strong><br />

jurisdiction<br />

9<br />

10<br />

Jurisdictional Error<br />

Condition Precedent<br />

12

Jurisdictional Error<br />

SMOKING (PUBLIC HEALTH)<br />

ORDINANCE (CAP 371)<br />

3 (1) <strong>The</strong> areas described in Part 1 <strong>of</strong> Schedule 2<br />

are designated as no smoking areas.<br />

…(2) No person shall smoke or carry a lighted<br />

cigarette, cigar or pipe in a no smoking area.<br />

13<br />

14<br />

SMOKING (PUBLIC HEALTH)<br />

ORDINANCE (CAP 371)<br />

Part 1 <strong>of</strong> Schedule 2:<br />

19. An indoor area in-<br />

(a) any shop, department store or shopping mall;<br />

(b) any market (whether publicly or privately<br />

operated or managed);<br />

(c) any supermarket;<br />

(d) any bank;<br />

(e) any restaurant premises;<br />

SMOKING (PUBLIC HEALTH)<br />

ORDINANCE (CAP 371)<br />

2. ”indoor" () means—<br />

(a) having a ceiling or ro<strong>of</strong>, or a cover that<br />

functions (whether temporarily or permanently)<br />

as a ceiling or ro<strong>of</strong>; and<br />

(b) enclosed (whether temporarily or<br />

permanently) at least up to 50% <strong>of</strong> the total area<br />

on all sides, except for any window or door, or<br />

any closeable opening that functions as a<br />

window or door;<br />

15<br />

16

A restaurant with an outdoor extension<br />

A restaurant with an outdoor extension<br />

• It has an extension outwards from the main premises up to the<br />

pavement.<br />

• It is covered by a blue canopy which functioned as a ro<strong>of</strong>.<br />

• Plastic curtains were hung on three sides <strong>of</strong> the canopy, except<br />

the side adjoining the main premises. <strong>The</strong>se curtains could be<br />

completely rolled up or unrolled to hang down to ground level.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> side <strong>of</strong> the extension fronting the pavement has an<br />

entrance with a door on its left portion, viewing it from the<br />

pavement, and there are flowerbeds to the right <strong>of</strong> the entrance.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> curtains on the left side <strong>of</strong> the extension (viewing it from<br />

the pavement) as well as those on the side fronting the<br />

pavement are rolled down.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> curtains on the right side <strong>of</strong> the extension is not rolled<br />

down.<br />

17<br />

18<br />

Jurisdictional error <strong>of</strong> law<br />

At least 50% <strong>of</strong> the total<br />

area <strong>of</strong> all sides must be<br />

enclosed, irrespective <strong>of</strong><br />

how the enclosed area is<br />

distributed among the<br />

various sides<br />

<strong>The</strong> cigarette<br />

is lighted.<br />

Jurisdictional error <strong>of</strong> fact<br />

Indoor: “at least up to 50% <strong>of</strong> the total area on all sides” is “at least<br />

50% <strong>of</strong> the total area <strong>of</strong> each and every side ”<br />

19<br />

No person shall smoke or carry a lighted cigarette, cigar or<br />

pipe in a no smoking area<br />

20

Non-Jurisdictional error <strong>of</strong> law<br />

A big hole on the curtain<br />

is considered to be a<br />

window and is excluded<br />

in calculating the total<br />

area. Total area still above<br />

50%.<br />

Non-Jurisdictional error <strong>of</strong> fact<br />

He is<br />

smoking a<br />

cigarette.<br />

Indoor: at least up to 50% <strong>of</strong> the total area on all sides, except for any<br />

window or door, or any closeable opening that functions as a window<br />

No person shall smoke or carry a lighted cigarette, cigar or<br />

pipe in a no smoking area<br />

or door 21<br />

22<br />

Issues that court will consider<br />

in <strong>Judicial</strong> <strong>Review</strong><br />

law<br />

as applied<br />

to the facts<br />

fairly<br />

Error <strong>of</strong> law<br />

23<br />

24

Error <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong><br />

Vallejos Evangeline Banao v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Registration and<br />

Another HCAL 124/2010<br />

1. Administrative decisions without<br />

legal basis<br />

(a) administrative decisions made on the basis <strong>of</strong><br />

an unconstitutional law<br />

<br />

Foreign Domestic Helpers cases<br />

25<br />

26<br />

Vallejos Evangeline Banao v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Registration and<br />

Another HCAL 124/2010<br />

Article 24(2)(4) <strong>of</strong> the Basic <strong>Law</strong>:<br />

“Persons not <strong>of</strong> Chinese nationality who have<br />

entered <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> with valid travel documents,<br />

have ordinarily resided in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> for a<br />

continuous period <strong>of</strong> not less than seven years and<br />

have taken <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> as their place <strong>of</strong> permanent<br />

residence before or after the establishment <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> Special Administrative Region.”<br />

Vallejos Evangeline Banao v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Registration and<br />

Another HCAL 124/2010<br />

Immigration Ordinance:<br />

“2(4) For the purposes <strong>of</strong> this Ordinance, a person<br />

shall not be treated as ordinarily resident in <strong>Hong</strong><br />

<strong>Kong</strong>-<br />

(a) during any period in which he remains in <strong>Hong</strong><br />

<strong>Kong</strong>…<br />

(vi) while employed as a domestic helper who is<br />

from outside <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong>…”<br />

27<br />

28

Vallejos Evangeline Banao v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Registration and<br />

Another HCAL 124/2010<br />

Article 154 <strong>of</strong> the Basic <strong>Law</strong>:<br />

“<strong>The</strong> Government <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> Special<br />

Administrative Region may apply immigration<br />

controls on entry into, stay in and departure from<br />

the Region by persons from foreign states and<br />

regions.”<br />

Vallejos Evangeline Banao v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Registration and<br />

Another HCAL 124/2010<br />

Meaning <strong>of</strong> ordinary residence:<br />

“…if there be proved a regular, habitual mode <strong>of</strong><br />

life in a particular place, the continuity <strong>of</strong> which<br />

has persisted despite temporary absences, ordinary<br />

residence is established provided only it is adopted<br />

voluntarily and for a settled purpose.”<br />

29<br />

30<br />

Vallejos Evangeline Banao v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Registration and<br />

Another HCAL 124/2010<br />

Meaning <strong>of</strong> settled purpose:<br />

“…[t]he purpose may be one; or there may be several. It may<br />

be specific or general. All that the law requires is that there is a<br />

settled purpose. This is not to say that the ‘propositus’ intends<br />

to stay where he is indefinitely; indeed his purpose, while<br />

settled, may be for a limited period. Education, business or<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ession, employment, health, family, or merely love <strong>of</strong> the<br />

place spring to mind as common reasons for a choice <strong>of</strong> regular<br />

abode. And there may well be many others. All that is necessary<br />

is that the purpose <strong>of</strong> living where one does has a sufficient<br />

degree <strong>of</strong> continuity to be properly described as settled.”<br />

31<br />

Vallejos Evangeline Banao v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Registration and<br />

Another HCAL 124/2010<br />

• V employed as a domestic helper in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> since 1986.<br />

• resided in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> for more than 22 years<br />

• integrated into the local community; has friends in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong>;<br />

active member <strong>of</strong> a church and participates in volunteer work <strong>of</strong><br />

the church in her free time; took various courses in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> in<br />

her spare time.<br />

• husband fully supported her plan and was willing to join her in<br />

<strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong>; children had grown up and married and had their<br />

own families and were financially independent; transferred her<br />

mini store and the purified water business in Philippine to her<br />

fourth son.<br />

• employer and his family members treated her as part <strong>of</strong> their<br />

family; supported her application as he wanted to employ her to<br />

look after his store; indicated that he would continue to provide<br />

accommodation to her upon the change <strong>of</strong> her status.<br />

32

Gutierrez Josephine B. v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Registration and Registration<br />

<strong>of</strong> Persons Tribunal HCAL 136/2010 and HCAL 137/2010<br />

• G has been working in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> as a foreign domestic helper<br />

since 1991. Her child, J, was born in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> on 1 December<br />

1996 and he is now almost 15 years old.<br />

• G has been in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> for almost 19 years; does not have a<br />

“home” in the Philippines; husband separated since 1992 and he is<br />

now living with another woman in the Philippines with whom he<br />

has two children; her children under this marriage are in the<br />

Philippines are all grown up and having their own lives; 2 <strong>of</strong> her<br />

other children are currently working in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> as FDHs; her<br />

mother is in the Philippines and is being supported by her other<br />

children.<br />

Gutierrez Josephine B. v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Registration and Registration<br />

<strong>of</strong> Persons Tribunal HCAL 136/2010 and HCAL 137/2010<br />

• She does not own any land or property in the Philippines; all <strong>of</strong><br />

her assets are located in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong>; has taken out a Lifetime<br />

Protection Plus policy with the HSBC that requires instalment<br />

payments up to the age <strong>of</strong> 65.<br />

• G developed her social circle in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong>; active member <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Kowloon Filipino Baptist Church; baptized into the Baptist faith<br />

in February 2003 and worships there every Sunday; takes part in<br />

the choir during services and is involved in sharing the gospel <strong>of</strong><br />

Christ with new people in the church<br />

• On the seven years immediately prior to the application <strong>of</strong> her<br />

son, there were three occasions when the son was away from<br />

<strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong>; on each occasion, upon his return, he was given<br />

permission to enter and remain in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> on visitor condition<br />

33<br />

34<br />

Gutierrez Josephine B. v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Registration and Registration<br />

<strong>of</strong> Persons Tribunal HCAL 136/2010 and HCAL 137/2010<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> First Instance:<br />

“…though it is ultimately for the court to decide what is the law<br />

pertaining to the ordinary residence and the permanence<br />

requirements, the primary decision maker who makes the relevant<br />

finding <strong>of</strong> facts and applies the facts to the law is the Director (and<br />

on appeal, the Tribunal). In respect <strong>of</strong> matters which fall within the<br />

primary remit <strong>of</strong> the Director, the court would only intervene on<br />

traditional judicial review grounds though examining the primary<br />

decisions with anxious scrutiny given the fundamental nature <strong>of</strong> the<br />

right being involved.<br />

… under this approach, ins<strong>of</strong>ar as the application <strong>of</strong> the relevant<br />

legal principle involves value judgments, the court would not<br />

disturb such value judgments on the part <strong>of</strong> the primary decision<br />

maker unless it is shown to be unreasonable on the enhanced<br />

Wednesbury standard.”<br />

35<br />

Gutierrez Josephine B. v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Registration and Registration<br />

<strong>of</strong> Persons Tribunal HCAL 136/2010 and HCAL 137/2010<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> First Instance:<br />

“<strong>The</strong> permanence requirement makes it necessary for the<br />

applicant to satisfy the Director both that he intends to<br />

establish his permanent home in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> and that he<br />

has taken concrete steps to do so. This means that the<br />

applicant must show that his residence here is intended to<br />

be more than ordinary residence and that he intends and<br />

has taken action to make <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong>, and <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong><br />

alone, his place <strong>of</strong> permanent residence.”<br />

36

Gutierrez Josephine B. v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Registration and<br />

Registration <strong>of</strong> Persons Tribunal HCAL 136/2010 and HCAL 137/2010<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> First Instance:<br />

“Before one can make a place his or her only permanent<br />

residence, he or she must take some concrete steps turning<br />

such aspiration into a realistic proposition in terms <strong>of</strong><br />

long term livelihood at that place. This can either be<br />

achieved by one’s independent means or the sponsorship <strong>of</strong><br />

other persons.<br />

If an applicant can produce evidence <strong>of</strong> such concrete step,<br />

then the evidence as to the severance <strong>of</strong> link with the<br />

country <strong>of</strong> origin would be relevant in making good a case<br />

<strong>of</strong> taking <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> as the only place <strong>of</strong> permanent<br />

residence. But an applicant cannot rely on the latter<br />

without the pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> the former. ”<br />

37<br />

Gutierrez Josephine B. v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Registration and<br />

Registration <strong>of</strong> Persons Tribunal HCAL 136/2010 and HCAL 137/2010<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> First Instance:<br />

“Applying the enhanced Wednesbury test, I am unable to<br />

say that the conclusion <strong>of</strong> the Tribunal is irrational or<br />

unreasonable. Nor do I see how the Tribunal can be<br />

criticized for failing to take relevant matters into account.<br />

As regards other matters on the list, none <strong>of</strong> them can<br />

really be regarded as concrete step towards taking <strong>Hong</strong><br />

<strong>Kong</strong> as the only permanent residence <strong>of</strong> the mother.<br />

…. unlike the successful applicant in HCAL 124 <strong>of</strong> 2010,<br />

there is no evidence to suggest that the employer would<br />

sponsor her livelihood in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> in support <strong>of</strong> her<br />

application for permanent residence.”<br />

38<br />

Error <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong><br />

1. Administrative decisions without<br />

legal basis<br />

(b) administrative decisions made on the basis <strong>of</strong> a<br />

subsidiary legislation which conflicted with the<br />

primary statute<br />

<br />

39<br />

Pang Tak Kwai v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Correctional<br />

Services and Another HCAL1610/2000<br />

• Pang, a Technical Instructor in the Correctional Services Department.<br />

• He was charged <strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>fence <strong>of</strong> possession <strong>of</strong> prohibited articles in<br />

prison contrary to section 18A(1)(a) <strong>of</strong> the Prisons Ordinance and was<br />

convicted.<br />

• Following his conviction, he was dismissed pursuant to rule 255B <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Prison Rules (Cap. 234):<br />

“(1) <strong>The</strong> punishment <strong>of</strong> a Chief Officer, subordinate <strong>of</strong>ficer or other<br />

person employed in the prisons who in criminal proceedings is found<br />

guilty <strong>of</strong> or pleads guilty to a criminal <strong>of</strong>fence shall be in accordance<br />

with this rule.<br />

(4) <strong>The</strong> Chief Executive may, after considering any representations<br />

made by the <strong>of</strong>ficer or person, award any one or more <strong>of</strong> the<br />

punishments he may award under rule 254(b) in respect <strong>of</strong> a<br />

disciplinary <strong>of</strong>fence by an <strong>of</strong>ficer (other than an Assistant Officer) or<br />

other person employed in the prisons.“<br />

40

Pang Tak Kwai v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Correctional<br />

Services and Another HCAL1610/2000<br />

• Rule 255B <strong>of</strong> the Prison Rules was enacted under section 25 <strong>of</strong><br />

the Prison Ordinance:<br />

“<strong>The</strong> Chief Executive in Council may make rules providing for …<br />

(d) the acts which shall be disciplinary <strong>of</strong>fences on the part <strong>of</strong> any<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficer <strong>of</strong> the Correctional Services Department or other person<br />

employed in the prisons and hostels;<br />

(da) the inquiry by the Commissioner, Deputy Commissioner or<br />

such other authority as may be prescribed into a disciplinary<br />

<strong>of</strong>fence by any such <strong>of</strong>ficer or other person;<br />

(db) the procedure to be followed in any case where a disciplinary<br />

<strong>of</strong>fence or a breach <strong>of</strong> duty is alleged to have been committed by<br />

any such <strong>of</strong>ficer or other person;<br />

(dc) the punishment, including-<br />

(i) dismissal….<strong>of</strong> such <strong>of</strong>ficer or other person for any disciplinary<br />

<strong>of</strong>fence;.....<br />

Pang Tak Kwai v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Correctional<br />

Services and Another HCAL1610/2000<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> First Instance:<br />

”<strong>The</strong> principle in this area is succinctly set out in Bennion on<br />

Statutory Interpretation 3rd Ed. section 58 : (1) Any provision<br />

<strong>of</strong> an instrument constituting delegated legislation is ineffective<br />

if the provision goes beyond the totality <strong>of</strong> the legislative power<br />

which (expressly or by implication) is conferred on the delegate<br />

by the enabling Act. <strong>The</strong> provision is then said to be ultra vires<br />

(beyond the powers). This applies even where the instrument<br />

has been sanctioned by a confirming authority. However the<br />

instrument is not to be treated as ineffective in any respect on<br />

the ground <strong>of</strong> ultra vires unless and until declared to be so by a<br />

court <strong>of</strong> competent jurisdiction.”<br />

(l) all other matters relating to the prisons and hostels.”<br />

41<br />

42<br />

Pang Tak Kwai v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Correctional<br />

Services and Another HCAL1610/2000<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> First Instance:<br />

“It is clear that section 25(1)(d), (da), (db) and (dc) are all<br />

in relation to disciplinary <strong>of</strong>fence. Unless such a criminal<br />

<strong>of</strong>fence is a disciplinary <strong>of</strong>fence <strong>of</strong> which rules for<br />

punishment can be made or comes within the general<br />

provision <strong>of</strong> “all other matters relating to the prisons and<br />

hostels” then the power <strong>of</strong> the Governor-in-Council who<br />

made rule 255B for the punishment <strong>of</strong> a person employed<br />

in prisons found guilty <strong>of</strong> criminal <strong>of</strong>fence was not<br />

authorized by the enabling section in section 25 <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Prisons Ordinance.”<br />

43<br />

Pang Tak Kwai v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Correctional<br />

Services and Another HCAL1610/2000<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> First Instance:<br />

“A ‘disciplinary <strong>of</strong>fence’ means a disciplinary <strong>of</strong>fence<br />

prescribed by rules made under section 25: section 2 <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Prisons Ordinance. Rule 239 provides that any <strong>of</strong>ficer <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Correctional Services Department or other persons employed in<br />

the prisons commits a disciplinary <strong>of</strong>fence who, for example,<br />

without good and sufficient cause fails to carry out any lawful<br />

order, whether written or verbal, or is subordinate towards any<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficer in the service <strong>of</strong> the Department whose orders it is for<br />

the time being his duty to obey. Rule 239 lists 18 such acts.<br />

It is clear that in order to ascertain whether an act is a<br />

‘disciplinary <strong>of</strong>fence’, one has to turn to rule 239 and<br />

nowhere else.”<br />

44

Pang Tak Kwai v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Correctional<br />

Services and Another HCAL1610/2000<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> First Instance:<br />

“As stated in Bennion at page 184 : ‘An enabling enactment<br />

frequently includes so-called 'sweeping-up words' intended to<br />

confer residual powers to complete those expressly spelt out.....<br />

<strong>The</strong> courts tend to regard such words as being strictly limited in<br />

scope. '..... "supplementary" means ... something added to what<br />

is in the Act to fill in details or machinery for which the Act<br />

itself does not provide -supplementary in the sense that it is<br />

required to implement what was in the Act'.’ Item (l) clearly<br />

cannot be used to complete what is expressly left out in<br />

section 25, namely rules providing for punishment <strong>of</strong> persons<br />

employed in prisons found guilty <strong>of</strong> a criminal <strong>of</strong>fence.”<br />

45<br />

2. Administrative decisions contravened<br />

the terms <strong>of</strong> legal authority<br />

-the statutory conditions for exercising an<br />

administrative power has not been satisfied<br />

<br />

Error <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong><br />

46<br />

Kwan Shung King v. Housing Appeal Tribunal<br />

HCAL 161/1999<br />

HOUSING ORDINANCE - SECT 19:<br />

“(1) Notwithstanding the terms there<strong>of</strong>, the<br />

Authority may terminate any lease-<br />

…(b) otherwise, by giving such notice to quit as<br />

may be provided for in the lease or 1 month's notice<br />

to quit, whichever is the greater.”<br />

Kwan Shung King v. Housing Appeal Tribunal<br />

HCAL 161/1999<br />

Standard-term Tenancy Agreement contains the<br />

following material terms:<br />

"(II) <strong>The</strong> Tenant agrees with the Landlord as follows:<br />

...(11) Not to use or cause or permit the said flat to be used<br />

for any illegal or immoral purpose.<br />

(IV) IT IS HEREBY expressly agreed as follows:<br />

... (7) For the purposes <strong>of</strong> this Agreement any act, neglect<br />

or default <strong>of</strong> any member <strong>of</strong> the Tenant's family or <strong>of</strong> any<br />

servant <strong>of</strong> his shall be deemed to be the act, neglect or<br />

default <strong>of</strong> the Tenant.”<br />

47<br />

48

Kwan Shung King v. Housing Appeal Tribunal<br />

HCAL 161/1999<br />

• Kwan, a tenant, entrusted the flat to his son who then<br />

entrusted it to his friend Fan. Fan was convicted <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>of</strong>fence <strong>of</strong> permitting a place to be used as a<br />

gambling establishment. Kwan alleged that he and<br />

his family members did not have knowledge that the<br />

unit was used for gambling.<br />

• Housing Appeal Tribunal confirming a notice to quit<br />

served by the Housing Authority on Kwan:<br />

“[Kwan], being the tenant <strong>of</strong> the unit, had<br />

abstained from taking reasonable steps to prevent<br />

Kwan Shung King v. Housing Appeal Tribunal<br />

HCAL 161/1999<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> First Instance:<br />

“While it may not be reasonable to confine the<br />

meaning <strong>of</strong> a "servant" in Clause 4(g) to a personal<br />

or domestic attendant or a person employed in a<br />

house to perform household duties, it certainly<br />

denotes a employer and employee relationship. <strong>The</strong><br />

plain meaning <strong>of</strong> the word "servant" does not<br />

cover a friend, a visitor or a relative.”<br />

the unit from being used for illegal purposes…”<br />

49<br />

50<br />

Kwan Shung King v. Housing Appeal Tribunal<br />

HCAL 161/1999<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> First Instance:<br />

“…'permit' means one <strong>of</strong> the two things, either to give<br />

leave for an act which without that could not be legally<br />

done, or to abstain from taking reasonable steps to<br />

prevent the act where it is within a man's power to<br />

prevent it…<br />

In my view, it is only within a man's power to prevent an<br />

act if the man has knowledge or at least suspicion that<br />

the act will be committed. <strong>The</strong>re is no suggestion that the<br />

Applicant or any <strong>of</strong> his family members could reasonably<br />

have foreseen that Fan would on that isolated occasion<br />

make use <strong>of</strong> the flat for gambling activities.”<br />

Kwan Shung King v. Housing Appeal Tribunal<br />

HCAL 161/1999<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> First Instance:<br />

“<strong>The</strong> Applicant might well have been a most irresponsible<br />

tenant by allowing others to have keys to the flat and did<br />

not care about the matter any more. But such irresponsible<br />

attitude is not abstaining from taking reasonable steps to<br />

prevent the flat from being used for illegal purpose when<br />

he could not have foreseen and had no reasonable<br />

suspicion that the flat would be so used.<br />

In the absence <strong>of</strong> a breach <strong>of</strong> the tenancy agreement, there<br />

was no valid basis upon which the Housing Authority<br />

could serve the notice to quit on the Applicant.”<br />

51<br />

52

3. Administrative decisions exceeded the<br />

scope <strong>of</strong> legal authority granted under a<br />

statute<br />

<br />

Error <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong><br />

Lam Siu Tai v <strong>The</strong> Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Correctional Services and the<br />

Secretary for the Civil Service<br />

[2000] 1 HKLRD A1; CA No. 25 <strong>of</strong> 2000<br />

• Lam, a prison <strong>of</strong>ficer, was found guilty <strong>of</strong> an <strong>of</strong>fence<br />

under the Prison Rules. He was heard by a<br />

Superintendent and was awarded a severe reprimand<br />

and a fine <strong>of</strong> $500.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Correctional Services<br />

reviewed the original punishment and awarded a<br />

new punishment <strong>of</strong> a severe reprimand and a fine <strong>of</strong><br />

$20,000.<br />

• Lam’s monthly salary was HK$53,000 when the<br />

Commissioner reviewed his punishment.<br />

53<br />

54<br />

Lam Siu Tai v <strong>The</strong> Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Correctional Services and the<br />

Secretary for the Civil Service<br />

[2000] 1 HKLRD A1; CA No. 25 <strong>of</strong> 2000<br />

Prison Rules, Rule 255C:,<br />

“…the Commissioner may, <strong>of</strong> his own motion,…<br />

review the … punishment…<br />

(2) Upon a review under this rule the<br />

Commissioner … may do any <strong>of</strong> the things<br />

described in rule 255F… (c) …”<br />

Lam Siu Tai v <strong>The</strong> Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Correctional Services and the<br />

Secretary for the Civil Service<br />

[2000] 1 HKLRD A1; CA No. 25 <strong>of</strong> 2000<br />

Prison Rules, Rule 255F:<br />

“Upon an appeal,… the Commissioner… may-<br />

…(c) ….substitute any other punishment which<br />

could have been awarded in the first instance;…”<br />

55<br />

56

Lam Siu Tai v <strong>The</strong> Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Correctional Services and the<br />

Secretary for the Civil Service<br />

[2000] 1 HKLRD A1; CA No. 25 <strong>of</strong> 2000<br />

Prison Rules, Rule 247:<br />

“<strong>The</strong> Superintendent may make any <strong>of</strong> the<br />

following disciplinary awards-<br />

(a) (i) administer a fine <strong>of</strong> an amount not exceeding<br />

1 day's pay;…”<br />

57<br />

Lam Siu Tai v <strong>The</strong> Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Correctional Services and the<br />

Secretary for the Civil Service<br />

[2000] 1 HKLRD A1; CA No. 25 <strong>of</strong> 2000<br />

Prison Rules, Rule 254:<br />

“A Chief Officer, subordinate <strong>of</strong>ficer (other than an<br />

Assistant Officer) or other person employed in the prisons<br />

who is found guilty <strong>of</strong> or pleads guilty to a disciplinary<br />

<strong>of</strong>fence may be punished by the award <strong>of</strong> any one or more<br />

<strong>of</strong> the following punishments-<br />

(a) by the Commissioner-<br />

…(iii)… forfeiture <strong>of</strong> pay (excluding allowances) for a<br />

period not exceeding one month or the period <strong>of</strong> absence,<br />

whichever is the greater;<br />

(iv) a fine not exceeding one month's salary (excluding<br />

allowances)…”<br />

58<br />

Lam Siu Tai v <strong>The</strong> Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Correctional Services and the<br />

Secretary for the Civil Service<br />

[2000] 1 HKLRD A1; CA No. 25 <strong>of</strong> 2000<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> First Instance:<br />

“<strong>The</strong> dispute concerns the meaning <strong>of</strong> the words ‘any other<br />

punishment which could have been awarded in the first<br />

instance’ in item (c) <strong>of</strong> Rule 255F. <strong>The</strong> Respondents argued<br />

that the increased fine is something that the Commissioner<br />

can impose in the first instance because <strong>of</strong> the provision <strong>of</strong><br />

Rule 254(a)(iv), namely a fine not exceeding one month's<br />

salary.<br />

In my view, the construction urged upon by the<br />

Respondents is wrong. Punishment which could have been<br />

awarded in the first instance, means punishment which<br />

could have been awarded by the Superintendent who<br />

heard the charge in the first instance.”<br />

59<br />

Error <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong><br />

4. Administrative decisions made on the<br />

basis <strong>of</strong> a legal error<br />

<br />

60

non-jurisdictional<br />

error <strong>of</strong> law:<br />

a valid decision<br />

61<br />

Chang Wing Tai, in the matter <strong>of</strong> an application by for<br />

leave to apply for judicial review<br />

MP No. 1987 <strong>of</strong> 1987<br />

• Chan was a shareholder in the Overseas Trust Bank. <strong>The</strong> assets <strong>of</strong><br />

the Bank were acquired by the government by the Overseas Trust<br />

Bank Acquisition Ordinance. <strong>The</strong> objects <strong>of</strong> the Ordinance are to<br />

provide for the acquisition by the government <strong>of</strong> the Bank, the<br />

compensation payable in respect <strong>of</strong> such acquisition and the<br />

carrying on <strong>of</strong> the business <strong>of</strong> the Bank.<br />

• S.10 <strong>of</strong> the Ordinance empowered the Financial Secretary to make<br />

such regulations as may be necessary for the implementation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

objects <strong>of</strong> the Ordinance. Under the Overseas Trust Bank<br />

(Compensation <strong>of</strong> Registered Holders <strong>of</strong> Shares) Regulations, a<br />

Tribunal was set up to assess the value <strong>of</strong> shares in the Bank. <strong>The</strong><br />

schedule <strong>of</strong> the Regulation lays down detailed criteria how shares<br />

in the bank are to be valued.<br />

62<br />

Chang Wing Tai, in the matter <strong>of</strong> an application by for<br />

leave to apply for judicial review<br />

MP No. 1987 <strong>of</strong> 1987<br />

• Para 3(a)(v) <strong>of</strong> the schedule <strong>of</strong> the regulation provides that:<br />

”3. For the purpose <strong>of</strong> making calculation under para 2 the Tribunal shall<br />

(a) disregard...<br />

(v) the possibility <strong>of</strong> any claim by the company against any director,<br />

servant, auditor, adviser or agent <strong>of</strong> the company and the effect that such<br />

events may have had on the amount to be calculated under that<br />

paragraph.”<br />

• Chan appeared before the Tribunal and alleged that para. 3(a)(v) was<br />

contrary to the stated purposes <strong>of</strong> the Ordinance and accordingly ultra<br />

vires. He argued that it was possible for the government to recover<br />

substantial sums from the auditors and/or directors. It was most unjust<br />

that the government may receive damages and the shareholders would in<br />

effect be excluded from any benefit from actions taken.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Tribunal, however, rejected the argument and decided that that<br />

paragraph was not ultra vires. Chan now applies for judicial review <strong>of</strong><br />

the Tribunal's decision on the value <strong>of</strong> the shares.<br />

63<br />

Chang Wing Tai, in the matter <strong>of</strong> an application by for<br />

leave to apply for judicial review<br />

MP No. 1987 <strong>of</strong> 1987<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court:<br />

“<strong>The</strong> important matter to be determined is whether it can be<br />

claimed that Mr. Justice Mortimer merely made an error in<br />

law on the face <strong>of</strong> his Decision or on the other hand<br />

whether it can be argued that he exceeded his jurisdiction.<br />

…<br />

I am … satisfied that Mr. Justice Mortimer did not exceed<br />

his jurisdiction when making the determination to the effect<br />

that para. 3(a)(v) <strong>of</strong> the schedule was not ultra vires. In<br />

such circumstances it is irrelevant to consider whether he<br />

was right or wrong. His determination that it was intra<br />

vires was the end <strong>of</strong> the matter and final.”<br />

64

error <strong>of</strong> law<br />

on the face <strong>of</strong> record:<br />

an exception to<br />

non-jurisdictional error <strong>of</strong> law<br />

not reviewable<br />

R. v. Northumberland Compensation Appeal Tribunal,<br />

ex parte Shaw [1952] 1 KB 338<br />

65<br />

66<br />

R. v. Northumberland Compensation Appeal Tribunal,<br />

ex parte Shaw [1952] 1 KB 338<br />

• Shaw was formerly the clerk to the West Hospital. He was<br />

dismissed and compensation was paid made under the National<br />

Health Service (Transfer <strong>of</strong> Offices and Compensation)<br />

Regulations, 1948.<br />

• According to the regulation, the term <strong>of</strong> service <strong>of</strong> Shaw would<br />

be taken into account in calculating his compensation. It was<br />

decided that only Shaw's service with the Hospital but not also<br />

his other service with the local government would be considered<br />

in determining his term <strong>of</strong> service. Being aggrieved by the<br />

amount <strong>of</strong> the compensation awarded to him, he referred the<br />

matter to the tribunal designated by the regulation. <strong>The</strong> tribunal<br />

agreed that the only service to be taken into account was the<br />

service with the Hospital.<br />

• Was the decision <strong>of</strong> the tribunal reviewable by the Court?<br />

R. v. Northumberland Compensation Appeal Tribunal,<br />

ex parte Shaw [1952] 1 KB 338<br />

Lord Denning:<br />

“…the Court <strong>of</strong> King's Bench has an inherent jurisdiction to<br />

control all inferior tribunals, not in an appellate capacity, but in a<br />

supervisory capacity. This control extends not only to seeing that<br />

the inferior tribunals keep within their jurisdiction, but also to<br />

seeing that they observe the law. <strong>The</strong> control is exercised by<br />

means <strong>of</strong> a power to quash any determination by the tribunal<br />

which, on the face <strong>of</strong> it, <strong>of</strong>fends against the law. <strong>The</strong> King's Bench<br />

does not substitute its own views for those <strong>of</strong> the tribunal, as a<br />

Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal would do. It leaves it to the tribunal to hear the<br />

case again, and in a proper case may command it to do so. When<br />

the King's Bench exercises its control over tribunals in this way, it<br />

is not usurping a jurisdiction which does not belong to it. It is only<br />

exercising a jurisdiction which it has always had.”<br />

67<br />

68

R. v. Northumberland Compensation Appeal Tribunal,<br />

ex parte Shaw [1952] 1 KB 338<br />

Lord Denning:<br />

“It will have been seen that throughout all the cases there is one<br />

governing rule: Certiorari is only available to quash a decision<br />

for error <strong>of</strong> law if the error appears on the face <strong>of</strong> the record.<br />

What, then, is the record?…the record must contain at least the<br />

document which initiates the proceedings; the pleadings, if<br />

any; and the adjudication; but not the evidence, nor the<br />

reasons, unless the tribunal chooses to incorporate them. If the<br />

tribunal does state its reasons, and those reasons are wrong in<br />

law, certiorari lies to quash the decision.<br />

…I am clearly <strong>of</strong> opinion that an error admitted openly in the<br />

face <strong>of</strong> the court can be corrected by certiorari as well as an<br />

error that appears on the face <strong>of</strong> the record. <strong>The</strong> decision must<br />

be quashed.”<br />

69<br />

Exclusion clause<br />

70<br />

An example <strong>of</strong> exclusion clause or ouster clauses<br />

Section 19, Housing Ordinance:<br />

(1) Notwithstanding the terms there<strong>of</strong>, the Authority may<br />

terminate any lease-<br />

(a) without notice, if ,in the opinion <strong>of</strong> the Authority, the<br />

land held under the lease has become unfit for human<br />

habitation, a nuisance, dangerous to health or unsafe…<br />

(3) No court shall have jurisdiction to hear any<br />

application for relief by or on behalf <strong>of</strong> a person whose<br />

lease has been terminated under subsection (1) in<br />

connection with such termination.<br />

Anisminic Ltd. v. Foreign Compensation Commission<br />

[1969] 2 AC 147<br />

Lord Reid:<br />

“It is a well established principle that a provision ousting the<br />

ordinary jurisdiction <strong>of</strong> the court must be construed strictly -<br />

meaning, I think, that, if such a provision is reasonably capable <strong>of</strong><br />

having two meanings, that meaning shall be taken which preserves<br />

the ordinary jurisdiction <strong>of</strong> the court.<br />

…Undoubtedly such a provision protects every determination<br />

which is not a nullity. But I do not think that it is necessary or<br />

even reasonable to construe the word ‘determination’ as<br />

including everything which purports to be a determination but<br />

which is in fact no determination at all.”<br />

71<br />

72

Anisminic Ltd. v. Foreign Compensation Commission<br />

[1969] 2 AC 147<br />

Anisminic Ltd. v. Foreign Compensation Commission<br />

[1969] 2 AC 147<br />

• Anisminic owned a mining property in Egypt.<br />

• Property in Egypt belonging to British subjects was<br />

sequestrated by the Egyptian Government in 1957.<br />

Anisminic sold its whole business in Egypt to TEDO.<br />

By this agreement Anisminic assigned to TEDO any<br />

claim they might have to receive compensation directly<br />

from the Egyptian Government: did not any claim it<br />

might have to receive something from the British<br />

Government.<br />

• In 1959, the Egyptian Government compensated the<br />

British Government and a lump sum was paid to the<br />

British Government.<br />

73<br />

74<br />

Anisminic Ltd. v. Foreign Compensation Commission<br />

[1969] 2 AC 147<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Foreign Compensation (Egypt) (Determination and Registration<br />

<strong>of</strong> Claims) Order 1959 made under Foreign Compensation Act, 1950<br />

authorized the Foreign Compensation Commission to deal with<br />

compensation payments made by the Egyptian Government. <strong>The</strong><br />

effect <strong>of</strong> the Order was to confer legal rights on persons who might<br />

previously have hoped or expected that in allocating any sums<br />

available discretion would be exercised in their favour. <strong>The</strong> order<br />

required that the applicant has to be:<br />

”(i)...the owner <strong>of</strong> the property or is the successor in title <strong>of</strong> such<br />

person; ....and (ii) that the person referred to as aforesaid and any<br />

person who became successor in title <strong>of</strong> such person ....... were British<br />

nationals.....”<br />

• Anisminic submitted a claim under the order to the Commission<br />

concerning its property that was sequestrated by the Egyptian<br />

Government but was rejected on the ground that his successor in title<br />

was not a British National.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> order included a clause stating that:<br />

”<strong>The</strong> determination by the commission <strong>of</strong> any application made to<br />

them under this Act shall not be called in question in any court <strong>of</strong><br />

Anisminic Ltd. v. Foreign Compensation Commission<br />

[1969] 2 AC 147<br />

Lord Reid:<br />

“It has sometimes been said that it is only where a tribunal acts<br />

without jurisdiction that its decision is a nullity. But in such cases<br />

the word ‘jurisdiction’ has been used in a very wide sense, and I<br />

have come to the conclusion that it is better not to use the term<br />

except in the narrow and original sense <strong>of</strong> the tribunal being<br />

entitled to enter on the inquiry in question. But there are many<br />

cases where, although the tribunal had jurisdiction to enter on<br />

the inquiry, it has done or failed to do something in the course <strong>of</strong><br />

the inquiry which is <strong>of</strong> such a nature that its decision is a nullity.<br />

It may have given its decision in bad faith. It may have made a<br />

decision which it had no power to make. It may have failed in the<br />

course <strong>of</strong> the inquiry to comply with the requirements <strong>of</strong> natural<br />

justice.”<br />

law.” 75<br />

76

Anisminic Ltd. v. Foreign Compensation Commission<br />

[1969] 2 AC 147<br />

Lord Reid:<br />

“It may in perfect good faith have misconstrued the provisions<br />

giving it power to act so that it failed to deal with the question<br />

remitted to it and decided some question which was not remitted<br />

to it. It may have refused to take into account something which it<br />

was required to take into account. Or it may have based its decision<br />

on some matter which, under the provisions setting it up, it had no<br />

right to take into account. I do not intend this list to be<br />

exhaustive. ...But if they reach a wrong conclusion as to the width<br />

<strong>of</strong> their powers, the court must be able to correct that - not because<br />

the tribunal has made an error <strong>of</strong> law, but because as a result <strong>of</strong><br />

making an error <strong>of</strong> law they have dealt with and based their<br />

decision on a matter with which, on a true construction <strong>of</strong> their<br />

powers, they had no right to deal. ”<br />

77<br />

Anisminic Ltd. v. Foreign Compensation Commission<br />

[1969] 2 AC 147<br />

Lord Reid:<br />

“…the words ‘and any person who became successor in title to<br />

such person’ in article 4 (1) (b) (ii) have no application to a case<br />

where the applicant is the original owner. It follows that the<br />

commission rejected the appellants’ claim on a ground which they<br />

had no right to take into account and that their decision was a<br />

nullity. I would allow this appeal. ”<br />

78<br />

4. Administrative decisions made on the<br />

basis <strong>of</strong> a legal error<br />

<br />

Error <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong><br />

every error <strong>of</strong> law is a<br />

jurisdictional error?<br />

Every error <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong> goes to jurisdiction?<br />

Positive:<br />

Lord Denning in Pearlman v. Keepers and<br />

Governors <strong>of</strong> Harrow School [1979] QB 56<br />

<br />

79<br />

80

Pearlman v. Keepers and Governors <strong>of</strong> Harrow School<br />

[1979] QB 56<br />

Pearlman v. Keepers and Governors <strong>of</strong> Harrow School<br />

[1979] QB 56<br />

• Pearlman had installed a full central-heating system in the<br />

premises. He applied to the County Count to have the rateable<br />

value <strong>of</strong> the premises be reduced in accordance with Schedule<br />

8, paragraph 1 (2) <strong>of</strong> the Housing Act 1974.<br />

• In order to qualify for a reduction, the improvement must be an<br />

“improvement made by the execution <strong>of</strong> works amounting to<br />

structural alteration, extension or addition.”<br />

• <strong>The</strong> County Court refused.<br />

• Schedule 8, paragraph 2 <strong>of</strong> the Housing Act 1974 provided that<br />

decision <strong>of</strong> the judge in the county court would be “final and<br />

conclusive.”<br />

• Was the decision <strong>of</strong> the county court reviewable?<br />

81<br />

82<br />

Pearlman v. Keepers and Governors <strong>of</strong> Harrow School<br />

[1979] QB 56<br />

Lord Denning:<br />

“It has been held that certiorari will issue to a county court judge if he acts without<br />

jurisdiction in the matter…If he makes a wrong finding on a matter on which his<br />

jurisdiction depends, he makes a jurisdictional error; and certiorari will lie to quash<br />

his decision: see Anisminic Ltd. v. Foreign Compensation Commission [1969] 2<br />

A.C. 147, 208, per Lord Wilberforce. But the distinction between an error which<br />

entails absence <strong>of</strong> jurisdiction - and an error made within the jurisdiction - is very<br />

fine. So fine indeed that it is rapidly being eroded.<br />

…So fine is the distinction that in truth the High Court has a choice before it<br />

whether to interfere with an inferior court on a point <strong>of</strong> law. If it chooses to interfere,<br />

it can formulate its decision in the words: ‘<strong>The</strong> court below had no jurisdiction to<br />

decide this point wrongly as it did.’ If it does not choose to interfere, it can say: ‘<strong>The</strong><br />

court had jurisdiction to decide it wrongly, and did so.’ S<strong>of</strong>tly be it stated, but that is<br />

the reason for the difference between the decision <strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal in<br />

Anisminic Ltd. v. Foreign Compensation Commission [1968] 2 Q.B. 862 and the<br />

House <strong>of</strong> Lords [1969] 2 A.C. 147.<br />

I would suggest that this distinction should now be discarded. <strong>The</strong> High Court has,<br />

and should have, jurisdiction to control the proceedings <strong>of</strong> inferior courts and<br />

tribunals by way <strong>of</strong> judicial review. When they go wrong in law, the High Court<br />

Pearlman v. Keepers and Governors <strong>of</strong> Harrow School<br />

[1979] QB 56<br />

Lord Denning:<br />

“..the judge made an error <strong>of</strong> law when he determined that the<br />

installation <strong>of</strong> a full central heating system was not a ‘structural<br />

alteration ... or addition’ to the house. His decision was made by the<br />

statute ‘final and conclusive.’ Those words do not exclude remedy by<br />

certiorari, that is, by judicial review. I would, therefore, allow the<br />

appeal and make an order quashing his decision…“<br />

should have power to put them right.“ 83<br />

84

Every error <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong> goes to jurisdiction?<br />

Re Racal Communication Ltd. [1981] AC 374<br />

Conditional (administrative<br />

tribunals):<br />

Lord Diplock in Re Racal Communication Ltd.<br />

[1981] AC 374 Lord Brwone Wilkinson in R v<br />

Lord President <strong>of</strong> the Privy Council, ex parte<br />

Page [1993] AC 682<br />

85<br />

86<br />

Re Racal Communication Ltd. [1981] AC 374<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Director <strong>of</strong> Public Prosecution applied to the High Court for<br />

an order to inspect the books <strong>of</strong> Company R on the ground that<br />

there is reasonable cause to believe that any <strong>of</strong>ficer <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Company committed an <strong>of</strong>fence in connection with the<br />

management <strong>of</strong> the company's affairs in accordance with s. 441 <strong>of</strong><br />

the Company Act 1948.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> application was rejected on the ground that s. 441 only<br />

applied to <strong>of</strong>fences committed in the course <strong>of</strong> the internal<br />

management <strong>of</strong> a company.<br />

• An appeal to the High Court's decision was made to the Court <strong>of</strong><br />

Appeal though s. 441 provided that the decision <strong>of</strong> a High Court<br />

judge on an application shall not be appealable.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal allowed the appeal.<br />

• Any error? Did the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal have the power to entertain<br />

an appeal concerning the decision <strong>of</strong> the High Court? Did the<br />

Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal have the power to review the decision <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Re Racal Communication Ltd. [1981] AC 374<br />

Lord Diplock:<br />

“In Anisminic [1969] 2 A.C. 147 this House was concerned only<br />

with decisions <strong>of</strong> administrative tribunals…It is a legal landmark;<br />

it has made possible the rapid development in England <strong>of</strong> a rational<br />

and comprehensive system <strong>of</strong> administrative law on the foundation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the concept <strong>of</strong> ultra vires. It proceeds on the presumption that<br />

where Parliament confers on an administrative tribunal or<br />

authority, as distinct from a court <strong>of</strong> law, power to decide<br />

particular questions defined by the Act conferring the power,<br />

Parliament intends to confine that power to answering the question<br />

as it has been so defined: and if there has been any doubt as to<br />

what that question is, this is a matter for courts <strong>of</strong> law to resolve<br />

in fulfilment <strong>of</strong> their constitutional role as interpreters <strong>of</strong> the<br />

written law and expounders <strong>of</strong> the common law and rules <strong>of</strong><br />

equity. So if the administrative tribunal or authority have asked<br />

themselves the wrong question and answered that, they have done<br />

something that the Act does not empower them to do and their<br />

decision is a nullity.”<br />

High Court? 87<br />

88

Re Racal Communication Ltd. [1981] AC 374<br />

Lord Diplock:<br />

“Parliament can, <strong>of</strong> course, if it so desires, confer upon<br />

administrative tribunals or authorities power to decide questions <strong>of</strong><br />

law as well as questions <strong>of</strong> fact or <strong>of</strong> administrative policy, but this<br />

requires clear words, for the presumption is that where a decisionmaking<br />

power is conferred on a tribunal or authority that is not a<br />

court <strong>of</strong> law, Parliament did not intend to do so. <strong>The</strong> breakthrough<br />

made by Anisminic [1969] 2 A.C. 147 was that, as<br />

respects administrative tribunals and authorities, the old<br />

distinction between errors <strong>of</strong> law that went to jurisdiction and<br />

errors <strong>of</strong> law that did not, was for practical purposes abolished.<br />

Any error <strong>of</strong> law that could be shown to have been made by them<br />

in the course <strong>of</strong> reaching their decision on matters <strong>of</strong> fact or <strong>of</strong><br />

administrative policy would result in their having asked themselves<br />

the wrong question with the result that the decision they reached<br />

would be a nullity.”<br />

89<br />

Re Racal Communication Ltd. [1981] AC 374<br />

Lord Diplock:<br />

“But there is no similar presumption that where a decision-making<br />

power is conferred by statute upon a court <strong>of</strong> law, Parliament did not<br />

intend to confer upon it power to decide questions <strong>of</strong> law as well as<br />

questions <strong>of</strong> fact. Whether it did or not and, in the case <strong>of</strong> inferior courts,<br />

what limits are imposed on the kinds <strong>of</strong> questions <strong>of</strong> law they are<br />

empowered to decide, depends upon the construction <strong>of</strong> the statute<br />

unencumbered by any such presumption. In the case <strong>of</strong> inferior courts<br />

where the decision <strong>of</strong> the court is made final and conclusive by the<br />

statute, this may involve the survival <strong>of</strong> those subtle distinctions<br />

formerly drawn between errors <strong>of</strong> law which go to jurisdiction and<br />

errors <strong>of</strong> law which do not that did so much to confuse English<br />

administrative law before Anisminic [1969] 2 A.C. 147; but upon any<br />

application for judicial review <strong>of</strong> a decision <strong>of</strong> an inferior court in a<br />

matter which involves, as so many do, interrelated questions <strong>of</strong> law, fact<br />

and degree the superior court conducting the review should not be astute<br />

to hold that Parliament did not intend the inferior court to have<br />

jurisdiction to decide for itself the meaning <strong>of</strong> ordinary words used in the<br />

statute to define the question which it has to decide.”<br />

90<br />

Re Racal Communication Ltd. [1981] AC 374<br />

Lord Diplock:<br />

“<strong>The</strong> High Court is not a court <strong>of</strong> limited jurisdiction and its<br />

constitutional role includes the interpretation <strong>of</strong> written laws. <strong>The</strong>re<br />

is thus no room for the inference that Parliament did not intend<br />

the High Court or the judge <strong>of</strong> the High Court acting in his<br />

judicial capacity to be entitled and, indeed, required to construe<br />

the words <strong>of</strong> the statute by which the question submitted to his<br />

decision was defined. <strong>The</strong>re is simply no room for error going to<br />

his jurisdiction, nor, as is conceded by counsel for the respondent,<br />

is there any room for judicial review. <strong>Judicial</strong> review is available as<br />

a remedy for mistakes <strong>of</strong> law made by inferior courts and tribunals<br />

only. Mistakes <strong>of</strong> law made by judges <strong>of</strong> the High Court acting in<br />

their capacity as such can be corrected only by means <strong>of</strong> appeal<br />

to an appellate court; and if, as in the instant case, the statute<br />

provides that the judge,s decision shall not be appealable, they<br />

cannot be corrected at all.”<br />

91<br />

R v Lord President <strong>of</strong> the Privy Council, ex parte Page<br />

[1993] AC 682<br />

• Page was appointed a lecturer in the Department <strong>of</strong> Philosophy<br />

at the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Hull. <strong>The</strong> letter stated: “<strong>The</strong> appointment<br />

may be terminated by either party on giving three months’<br />

notice in writing expiring at the end <strong>of</strong> a term or <strong>of</strong> the long<br />

vacation.”<br />

• As a lecturer, Mr Page became a member <strong>of</strong> the university<br />

which is a corporate body regulated by Royal Charter. Section<br />

34 <strong>of</strong> the statutes made under the charter provides:<br />

“1. <strong>The</strong> vice-chancellor and all <strong>of</strong>ficers <strong>of</strong> the university<br />

including pr<strong>of</strong>essors and members <strong>of</strong> the staff holding their<br />

appointments until the age <strong>of</strong> retirement may be removed by<br />

the council for good cause… 3. Subject to the terms <strong>of</strong> his<br />

appointment no member <strong>of</strong> the teaching research or<br />

administrative staff <strong>of</strong> the university (including the vicechancellor)<br />

shall be removed from <strong>of</strong>fice save upon the<br />

grounds specified in paragraph 2 <strong>of</strong> this section and in<br />

pursuance <strong>of</strong> the procedure specified in clause 1 <strong>of</strong> this section.”<br />

• Section 34(2) defines the meaning <strong>of</strong> "good cause.”<br />

92

R v Lord President <strong>of</strong> the Privy Council, ex parte Page<br />

[1993] AC 682<br />

• Page was given three months' notice terminating his<br />

appointment on the grounds <strong>of</strong> redundancy. It is common<br />

ground that there was no “good cause” within the meaning <strong>of</strong><br />

section 34; the university was relying on the three months’<br />

notice term contained in the letter <strong>of</strong> appointment.<br />

• Mr Page took the view that on the true construction <strong>of</strong> section<br />

34 <strong>of</strong> the statutes the university had no power to remove him<br />

from <strong>of</strong>fice and terminate his employment save for good cause.<br />

• Mr Page started an action for wrongful dismissal which action<br />

was struck out on the grounds that the matter fell within the<br />

exclusive jurisdiction <strong>of</strong> the visitor <strong>of</strong> the university, Her<br />

Majesty the Queen.<br />

• Mr Page then petitioned the visitor for a declaration that his<br />

purported dismissal was ultra vires and <strong>of</strong> no effect. <strong>The</strong> petition<br />

was considered by the Lord President <strong>of</strong> the Council, on behalf<br />

<strong>of</strong> Her Majesty. <strong>The</strong> petition was dismissed by the visitor.<br />

• Mr Page then applied by way <strong>of</strong> judicial review for an order<br />

R v Lord President <strong>of</strong> the Privy Council, ex parte Page<br />

[1993] AC 682<br />

LORD BROWNE-WILKINSON:<br />

“In my judgment the decision in Anisminic Ltd v Foreign<br />

Compensation Commission [1969] 2 AC 147 rendered<br />

obsolete the distinction between errors <strong>of</strong> law on the face <strong>of</strong><br />

the record and other errors <strong>of</strong> law by extending the doctrine<br />

<strong>of</strong> ultra vires. <strong>The</strong>nceforward it was to be taken that<br />

Parliament had only conferred the decision-making power<br />

on the basis that it was to be exercised on the correct legal<br />

basis: a misdirection in law in making the decision therefore<br />

rendered the decision ultra vires…in general any error <strong>of</strong><br />

law made by an administrative tribunal or inferior court<br />

in reaching its decision can be quashed for error <strong>of</strong> law.”<br />

quashing the visitor's decision. 93<br />

94<br />

R v Lord President <strong>of</strong> the Privy Council, ex parte Page<br />

[1993] AC 682<br />

LORD BROWNE-WILKINSON:<br />

“Although the general rule is that decisions affected by<br />

errors <strong>of</strong> law made by industrial tribunals or inferior courts<br />

can be quashed, in my judgment…the rule does not apply in<br />

the case <strong>of</strong> visitors.<br />

In re A Company [1981] AC 374…Lord Diplock pointed<br />

out, at pp 382-383, that the decision in Anisminic Ltd v<br />

Foreign Compensation Commission [1969] 2 AC 147<br />

applied to decisions <strong>of</strong> administrative tribunals or other<br />

administrative bodies made under statutory powers: in those<br />

cases there was a presumption that the statute conferring<br />

the power did not intend the administrative body to be the<br />

final arbiter <strong>of</strong> questions <strong>of</strong> law.“<br />

95<br />

R v Lord President <strong>of</strong> the Privy Council, ex parte Page<br />

[1993] AC 682<br />

LORD BROWNE-WILKINSON:<br />

“He then contrasted that position with the case where a<br />

decision-making power had been conferred on a court <strong>of</strong><br />

law. In that case no such presumption could exist: on the<br />

contrary where Parliament had provided that the decision <strong>of</strong><br />

an inferior court was final and conclusive the High Court<br />

should not be astute to find that the inferior court's decision<br />

on a question <strong>of</strong> law had not been made final and<br />

conclusive, thereby excluding the jurisdiction to review it.<br />

In my judgment…there is no jurisdiction in the court to<br />

review a visitor's decision for error <strong>of</strong> law committed<br />

within his jurisdiction.”<br />

96

Every error <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong> goes to jurisdiction?<br />

S.E. Asia Fire Bricks v. Non-Metallic Products<br />

[1981] AC 363<br />

Negative:<br />

<strong>Judicial</strong> Committee <strong>of</strong> the Privy Council in<br />

S.E. Asia Fire Bricks v. Non-Metallic<br />

Products [1981] AC 363<br />

<br />

97<br />

98<br />

S.E. Asia Fire Bricks v. Non-Metallic Products<br />

[1981] AC 363<br />

• <strong>The</strong>re was a dispute between S Company and its<br />

employees.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> dispute was referred to the Industrial Court in<br />

accordance with the Industrial Relations Act 1967.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Industrial Court decided in favour <strong>of</strong> the employees.<br />

• Section 29 <strong>of</strong> the Industrial Relations Act 1967 provided<br />

that an award <strong>of</strong> the Industrial Court shall be final and<br />

conclusive, and no award shall be called in question in<br />

any court <strong>of</strong> law.<br />

• Was the decision <strong>of</strong> the Industrial Court reviewable?<br />

99<br />

S.E. Asia Fire Bricks v. Non-Metallic Products<br />

[1981] AC 363<br />

<strong>Judicial</strong> Committee <strong>of</strong> the Privy Council<br />

“<strong>The</strong> decision <strong>of</strong> the House <strong>of</strong> Lords in Anisminic Ltd. v. Foreign Compensation<br />

Commission [1969] 2 A.C. 147 shows that, when words in a statute oust the power<br />

<strong>of</strong> the High Court to review decisions <strong>of</strong> an inferior tribunal by certiorari, they must<br />

be construed strictly, and that they will not have the effect <strong>of</strong> ousting that power if<br />

the inferior tribunal has acted without jurisdiction or if ‘it has done or failed to do<br />

something in the course <strong>of</strong> the inquiry which is <strong>of</strong> such a nature that its decision is a<br />

nullity’: per Lord Reid at p. 171. But if the inferior tribunal has merely made an<br />

error <strong>of</strong> law which does not affect its jurisdiction, and if its decision is not a nullity<br />

for some reason such as breach <strong>of</strong> the rules <strong>of</strong> natural justice, then the ouster will be<br />

effective. In Pearlman v. Keepers and Governors <strong>of</strong> Harrow School [1979] Q.B.<br />

56, 70, Lord Denning M.R. suggested that the distinction between an error <strong>of</strong> law<br />

which affected jurisdiction and one which did not should now be "discarded."<br />

<strong>The</strong>ir Lordships do not accept that suggestion.<br />

…the error or errors did not affect the jurisdiction <strong>of</strong> the Industrial Court and their<br />

Lordships are therefore <strong>of</strong> opinion that section 29 (3) (a) effectively ousted the<br />

jurisdiction <strong>of</strong> the High Court to quash the decision by certiorari proceedings. “<br />

100

Every error <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong> goes to jurisdiction?<br />

Approach <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> courts:<br />

Positive<br />

Conditional<br />

Negative <br />

101<br />

Chang Wing Tai, in the matter <strong>of</strong> an application by for<br />

leave to apply for judicial review<br />

MP No. 1987 <strong>of</strong> 1987<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court:<br />

“<strong>The</strong> important matter to be determined is whether<br />

it can be claimed that Mr. Justice Mortimer merely<br />

made an error in law on the face <strong>of</strong> his Decision or<br />

on the other hand whether it can be argued that he<br />

exceeded his jurisdiction.<br />

Lord Fraser deals with this distinction at page 370<br />

<strong>of</strong> S.E. Asia Fire Bricks v. Non-Metallic Products<br />

[1981] AC 363 (P.C.). He rejects the suggestion<br />

made by Lord Denning in Pearlman v. Keepers<br />

[1979] 1 Q.B. 57 that the time had come to discard<br />

such a distinction.”<br />

102<br />

Jill Spruce v <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> (Court <strong>of</strong><br />

Appeal) [1991] 2 HKLR 444<br />

103<br />

Jill Spruce v <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> (Court <strong>of</strong><br />

Appeal) [1991] 2 HKLR 444<br />

• Jill was a senior lecturer <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong>.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> the contract between Jill and the <strong>University</strong> were contained<br />

in the letter <strong>of</strong> appointment and the pamphlet named "Term <strong>of</strong> Service I”:<br />

"4. (e) i. A teacher may engage in outside practice....outside <strong>of</strong> or in<br />

addition to his <strong>University</strong> duties, in accordance with such regulations as<br />

the Council may from time to time, but not to the detriment <strong>of</strong> the<br />

performance <strong>of</strong> his <strong>University</strong> duties....<br />

11. <strong>The</strong> <strong>University</strong> may at any time terminate the appointment <strong>of</strong> an<br />

appointee... subject to the provisions <strong>of</strong> s.12(9) <strong>of</strong> the Ordinance.”<br />

• <strong>The</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> Ordinance provides that:<br />

"2(2) 'Good Cause' means such inability to perform efficiently the<br />

duties <strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>fice, neglect <strong>of</strong> duty, or such misconduct, whether in an<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficial or a private capacity, as rendered the holder unfit to continue in<br />

<strong>of</strong>fice...<br />

12..(9)...<strong>The</strong> Council shall not terminate the appointment <strong>of</strong> any teacher<br />

except where after due enquiry into the facts and after receiving the<br />

advice <strong>of</strong> the Senate on the findings <strong>of</strong> such enquiry there exists in the<br />

opinion <strong>of</strong> the Council good cause for such termination.”<br />

104

Jill Spruce v <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> (Court <strong>of</strong><br />

Appeal) [1991] 2 HKLR 444<br />

• Provisions for consent to outside practice by teachers are to be found in<br />

the “Memorandum <strong>of</strong> Guidance and Regulations Governing Outside<br />

Practice by Teachers” approved by the Council <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong>. <strong>The</strong><br />

Memorandum and Regulations were found in the Staff Manual. It was<br />

stated that the Staff Manual was issued for information only and did not<br />