fairly - Faculty of Law, The University of Hong Kong

fairly - Faculty of Law, The University of Hong Kong

fairly - Faculty of Law, The University of Hong Kong

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

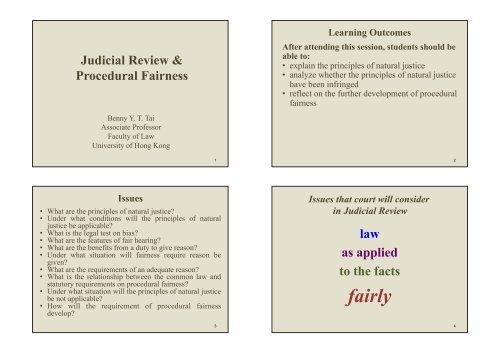

Learning Outcomes<br />

Judicial Review &<br />

Procedural Fairness<br />

After attending this session, students should be<br />

able to:<br />

• explain the principles <strong>of</strong> natural justice<br />

• analyze whether the principles <strong>of</strong> natural justice<br />

have been infringed<br />

• reflect on the further development <strong>of</strong> procedural<br />

fairness<br />

Benny Y. T. Tai<br />

Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor<br />

<strong>Faculty</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Law</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong><br />

1<br />

2<br />

Issues<br />

• What are the principles <strong>of</strong> natural justice?<br />

• Under what conditions will the principles <strong>of</strong> natural<br />

justice be applicable?<br />

• What is the legal test on bias?<br />

• What are the features <strong>of</strong> fair hearing?<br />

• What are the benefits from a duty to give reason?<br />

• Under what situation will fairness require reason be<br />

given?<br />

• What are the requirements <strong>of</strong> an adequate reason?<br />

• What is the relationship between the common law and<br />

statutory requirements on procedural fairness?<br />

• Under what situation will the principles <strong>of</strong> natural justice<br />

be not applicable?<br />

• How will the requirement <strong>of</strong> procedural fairness<br />

develop?<br />

Issues that court will consider<br />

in Judicial Review<br />

law<br />

as applied<br />

to the facts<br />

<strong>fairly</strong><br />

3<br />

4

Council <strong>of</strong> Civil Service Unions v. Minister for the<br />

Civil Services [1985] A.C. 374, Lord Diplock <br />

“I have described the third head as ‘procedural<br />

impropriety’ rather than failure to observe basic<br />

rules <strong>of</strong> natural justice or failure to act with<br />

procedural fairness towards the person who will<br />

be affected by the decision. This is because<br />

susceptibility to judicial review under this head<br />

covers also failure by an administrative tribunal<br />

to observe procedural rules that are expressly<br />

laid down in the legislative instrument by which<br />

its jurisdiction is conferred, even where such<br />

failure does not involve any denial <strong>of</strong> natural<br />

justice.“ <br />

5<br />

R v. Home Secretary, ex parte Doody [1994] 1 AC 531,<br />

at 560, Lord Mustill <br />

“What does fairness required in the present case? My<br />

Lords, I think it unnecessary to refer by name or to quote<br />

from, any <strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>ten-cited authorities in which the courts<br />

have explained what is essentially an intuitive judgment.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y are far too well known. From them, I derive that (1)<br />

where an Act <strong>of</strong> Parliament confers an administrative<br />

power there is a presumption that it will be exercised in a<br />

manner which is fair in all the circumstances. (2) <strong>The</strong><br />

standards <strong>of</strong> fairness are not immutable. <strong>The</strong>y may change<br />

with the passage <strong>of</strong> time, both in the general and in their<br />

application to decisions <strong>of</strong> a particular type. (3) <strong>The</strong><br />

principles <strong>of</strong> fairness are not to be applied by rote<br />

identically in every situation. What fairness demands is<br />

dependent on the context <strong>of</strong> the decision, and this is to be<br />

taken into account in all its aspects.“ 6<br />

R v. Home Secretary, ex parte Doody [1994] 1 AC 531,<br />

at 560, Lord Mustill <br />

“ (4) An essential feature <strong>of</strong> the context is the statute<br />

which creates the discretion, as regards both its language<br />

and the shape <strong>of</strong> the legal and administrative system<br />

within which the decision is taken. (5) Fairness will very<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten require that a person who may be adversely affected<br />

by the decision will have an opportunity to make<br />

representations on his own behalf either before the<br />

decision is taken with a view to producing a favourable<br />

result; or after it is taken, with a view to procuring its<br />

modification; or both. (6) Since the person affected<br />

usually cannot make worthwhile representations without<br />

knowing what factors may weigh against his interests<br />

fairness will very <strong>of</strong>ten require that he is informed <strong>of</strong> the<br />

gist <strong>of</strong> the case which he has to answer.“ <br />

7<br />

Leung Fuk Wah Oil v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Police<br />

CACV 2744/2001<br />

• Leung was a sergeant <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> Police. He was in<br />

serious financial difficulties. He was charged with two<br />

disciplinary <strong>of</strong>fences, pursuant to section 3(2)(e) <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Police (Discipline) Regulations for failing to be prudent<br />

in his financial affairs by incurring unmanageable size <strong>of</strong><br />

debts whereby his efficiency as a police <strong>of</strong>ficer was<br />

impaired.<br />

• A disciplinary hearing took place in early 1999. A<br />

Superintendent was appointed as the appropriate Tribunal.<br />

Leung was found guilty <strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>fence on 28 March 1999.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Tribunal then referred the punishment to a Senior<br />

Police Officer who imposed a penalty <strong>of</strong> reduction to the<br />

rank <strong>of</strong> police constable and dismissal from the force.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Force Disciplinary Officer confirmed the finding <strong>of</strong><br />

guilt and penalty.<br />

8

Leung Fuk Wah Oil v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Police<br />

CACV 2744/2001<br />

• Leung then appealed to the Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Police. <strong>The</strong><br />

Deputy Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Police exercising the delegated<br />

authority <strong>of</strong> the Commissioner dismissed the appeal.<br />

• Leung applied for judicial review to quash the decisions<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Tribunal, the Senior Police Officer and the Deputy<br />

Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Police on the ground that certain<br />

documents considered by the Deputy Commissioner<br />

were not disclosed to him.<br />

• Hartman J. dismissed the application in respect <strong>of</strong> the<br />

decisions <strong>of</strong> the Tribunal and the Senior Police Officer.<br />

However, he quashed the decision <strong>of</strong> the Deputy<br />

Commissioner.<br />

• Both Leung and the Commissioner appealed.<br />

9<br />

Leung Fuk Wah Oil v. Commissioner <strong>of</strong> Police<br />

CACV 2744/2001<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal:<br />

“Fairness requires the material to be disclosed so that the appellant<br />

may have a chance to respond to it.…the judge was right when he<br />

considered that the material needed to be disclosed as a matter <strong>of</strong><br />

fairness…<strong>The</strong> real question in this appeal is whether the nondisclosure<br />

vitiates the decision <strong>of</strong> the Commissioner and requires it<br />

to be quashed.<br />

…Having considered all the circumstances <strong>of</strong> this case, it is<br />

abundantly clear that the disclosure <strong>of</strong> the new documents to Mr.<br />

Leung would not have made the slightest difference to his petition<br />

to the Commissioner…<br />

Judicial review is a discretionary remedy. If the breach <strong>of</strong> the<br />

principle <strong>of</strong> fairness does not produce a substantial prejudice to<br />

the applicant, the court is bound to take this into account in<br />

deciding whether relief should be given. This is consistent with the<br />

concept that the court should not substitute its own decision for that<br />

<strong>of</strong> the decision-maker.“ 10<br />

ULTRA VIRES &<br />

Procedural Fairness<br />

Judicial Review and Procedural Fairness<br />

Three rules <strong>of</strong> natural justice (duty to act<br />

<strong>fairly</strong>)<br />

• <strong>The</strong> First Rule: Right to Unbiased Decision<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Second Rule: Right to Fair Hearing<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Third Rule: Right to reason<br />

<br />

11<br />

12

Procedural Fairness<br />

Right to Unbiased<br />

Decision<br />

<br />

Right to Fair Hearing<br />

<br />

Right to reason<br />

<br />

Before the decision is<br />

made <br />

During the making <strong>of</strong><br />

the decision<br />

After the decision<br />

is made <br />

Michael Rowse<br />

v.<br />

Secretary for the Civil Service<br />

and Others<br />

HCAL 41/2007<br />

13<br />

14<br />

Background<br />

• After SARS in 2003, the Chief Executive<br />

announced an economic relaunch campaign.<br />

• Michael Morse (MR), Director-General <strong>of</strong><br />

Investment Promotion, head <strong>of</strong> Invest HK<br />

acted as the Secretary <strong>of</strong> Economic Relaunch<br />

Working Group (ERWG) and Economic<br />

Relaunch Strategy Group (ERSG).<br />

• HK$1 billion was budgeted under the control<br />

<strong>of</strong> Invest HK.<br />

Background<br />

• In June 2003, MR was approached by Mr James<br />

Thompson, Chairman <strong>of</strong> the American Chamber<br />

<strong>of</strong> Commerce in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong>.<br />

• Mr Thompson proposed an international<br />

entertainment festival should be held.<br />

• In early July 2003, AmCham made a formal<br />

presentation to ERWG; the festival was to consist<br />

<strong>of</strong> a number <strong>of</strong> pop concerts featuring<br />

internationally known actors.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> ERWG approved AmCham‘s proposal in<br />

principle subject to Invest HK‘s scrutiny <strong>of</strong>, and<br />

satisfaction with, AmCham‘s detailed budget.<br />

15<br />

16

Background<br />

• Invest HK reviewed the proposed budget.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> budget was very roughly drawn, especially in<br />

respect <strong>of</strong> ‘talent‘ costs which were estimated to<br />

make up some 70% <strong>of</strong> the budget.<br />

• Performers were listed; no negotiations had been<br />

concluded; the list was aspirational and the costs<br />

were broadly indicative.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> ERWG prepared to work with the initial<br />

proposed budget and approved a maximum <strong>of</strong> HK<br />

$100 million for festival.<br />

17<br />

Background<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Harbour Fest fell far short <strong>of</strong> expectations. Media<br />

comment was generally negative. Members <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Legislative Council expressed concern.<br />

• In October 2003, the Audit Commission commenced its<br />

review.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Audit Commission observed that many <strong>of</strong> the problems<br />

had arisen because “too little time was available to do too<br />

many things.“<br />

• In November 2003, the Chief Executive appointed an<br />

Independent Panel to inquire into the handling <strong>of</strong> the<br />

festival.<br />

• In its report, the Independent Panel was critical <strong>of</strong> MR,<br />

finding that, as Government‘s controlling <strong>of</strong>ficer, he had not<br />

adequately discharged his responsibilities.<br />

• Chief Executive directed that disciplinary action against MR<br />

be held.<br />

18<br />

Background<br />

• An Inquiry Committee was appointed by the<br />

Secretary for the Civil Service, acting under<br />

delegated authority.<br />

• Two members <strong>of</strong> the Committee: Chairman,<br />

Mr Wilfred Tsui, the Judiciary Administrator<br />

and Mr Lo Yiu Ching JP, the Permanent<br />

Secretary for the Environment, Transport and<br />

Works (Works)<br />

19<br />

Five Charges<br />

<strong>The</strong>re were five charges <strong>of</strong> misconduct:<br />

(a) failing to ensure that the budget proposed critically examined<br />

by Invest HK and that the ERWG was fully and adequately<br />

advised on the proposed budget (substantiated);<br />

(b) failing to ensure that an effective mechanism was in place to<br />

enable the Government to monitor the organisation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Harbour Fest properly and to ensure that the Government‘s<br />

interest in the use <strong>of</strong> public funds allocated to the festival was<br />

adequately protected (partially substantiated);<br />

(c) failing to ensure that the Government‘s interests were adequately<br />

protected in the sponsorship contract (partially substantiated);<br />

(d) failing to ensure that a critical review <strong>of</strong> ticket pricing strategy<br />

was carried out thereby prejudicing the Government‘s position<br />

(partially substantiated);<br />

(e) failing to establish procedures and mechanisms whereby a<br />

detailed budget and all statements <strong>of</strong> account in relation to the<br />

festival would be subject to the scrutiny and approval by Invest<br />

HK prior to and during the course <strong>of</strong> the festival as a result <strong>of</strong><br />

which the Government‘s interests in the proper monitoring <strong>of</strong><br />

the festival were prejudiced (partially substantiated).<br />

20

Background<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Secretary for the Civil Service accepted the<br />

Inquiry Committee‘s findings in full and imposed<br />

penalty:<br />

– a severe reprimand<br />

– a fine equivalent to reduction in salary by two<br />

increments for 12 months<br />

– a caution that, in the event <strong>of</strong> further misconduct,<br />

serious consideration would be given to removing<br />

MR from the Civil Service<br />

• MR applied for judicial review.<br />

Issue 1:<br />

Impartiality <strong>of</strong> the Inquiry Committee<br />

• Tsui, in anticipation <strong>of</strong> his retirement, had made<br />

an application for the waiver <strong>of</strong> the ‘sanitisation‘<br />

period; that is, the period during which,<br />

immediately following his retirement, he could<br />

not take up other work; delayed making his<br />

application for a waiver <strong>of</strong> his sanitisation<br />

period until after the report had been submitted<br />

and the Secretary for the Civil Service had<br />

accepted its findings.<br />

21<br />

22<br />

Issue 1:<br />

Impartiality <strong>of</strong> the Inquiry Committee<br />

• Lo, with his retirement also looming, was the subject <strong>of</strong> an<br />

application made by his department for his re-employment.<br />

- <strong>The</strong>re was no delay in the application.<br />

- Lo had been appointed to the Inquiry Committee some three<br />

months before the application for his re-employment.<br />

- Though the application stood to benefit him, it was essentially<br />

incidental. <strong>The</strong> application was made for the benefit <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Bureau to meet its operational needs.<br />

- <strong>The</strong> application was first subject to the scrutiny <strong>of</strong> an<br />

independent statutory body, Public Service Commission,<br />

whose concern would be solely the operational needs and<br />

succession planning. This would place constraints on the final<br />

decision-making discretion <strong>of</strong> the Secretary for the Civil<br />

Service.<br />

23<br />

Issue 1:<br />

Impartiality <strong>of</strong> the Inquiry Committee<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Secretary for the Civil Service, who had<br />

appointed both Committee members, and to<br />

whom their report would be submitted, was the<br />

person who would finally decide, or be materially<br />

instrumental in deciding, whether to grant the two<br />

applications.<br />

• Any apparent bias?<br />

24

Issue 1:<br />

Impartiality <strong>of</strong> the Inquiry Committee<br />

• Test for apparent bias: “<strong>The</strong> Court must<br />

f i r s t a s c e r t a i n a l l t h e r e l e v a n t<br />

circumstances and then ask whether those<br />

circumstances would lead a fair-minded<br />

and informed observer to conclude there<br />

was a real possibility that the tribunal was<br />

biased.“<br />

Deacons v. White & Case Ltd Liability<br />

Partnership (2003) 6 HKCFAR 322.<br />

25<br />

Issue 1:<br />

Impartiality <strong>of</strong> the Inquiry Committee<br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“…the applicant‘s concerns in respect <strong>of</strong> Mr Tsui were set<br />

to one side when, among other things, he learnt that Mr Tsui<br />

had delayed making his application for a waiver <strong>of</strong> his<br />

sanitisation period until after the report had been<br />

submitted and the Secretary for the Civil Service had<br />

accepted its findings.“<br />

26<br />

Issue 1:<br />

Impartiality <strong>of</strong> the Inquiry Committee<br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“An informed observer would, <strong>of</strong> course, have been aware <strong>of</strong> the fact<br />

that Mr Lo had been appointed to the Inquiry Committee as far back<br />

as late September 2004, some three months before the application for<br />

his re-employment. An informed observer would also have been<br />

aware <strong>of</strong> the process by which all applications <strong>of</strong> the kind made by Mr<br />

Lo were processed; namely:<br />

• <strong>The</strong> application would only have been made by the Bureau itself<br />

on the basis <strong>of</strong> operational need.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> application would have been referred to the Public Service<br />

Commission, an independent statutory body, which would have<br />

considered the application on the merits.<br />

• Any decision made by the Secretary for the Civil Service to reemploy<br />

Mr Lo would only have been made if the Public Service<br />

Commission – as it did in the present case – had given its approval.<br />

…I do not believe that it would have given rise in the mind <strong>of</strong> a fairminded,<br />

independent observer to a real possibility that Mr Lo, and<br />

through him the Committee itself, may have been biased.“<br />

27<br />

Issue 2: Standard <strong>of</strong> Pro<strong>of</strong><br />

Duty <strong>of</strong> a disciplinary tribunal:<br />

– not under any obligation to expressly state what<br />

standard <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong>;<br />

– but if a disciplinary tribunal chooses to give some<br />

indication <strong>of</strong> the standard <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong> it has adopted, it<br />

should do so in terms that make it clear it has<br />

adopted the correct standard;<br />

– a failure to do so may indicate that the Tribunal has<br />

not fully understood the correct test to be applied<br />

and that it could not therefore, in the systematic<br />

manner demanded, have applied the correct test.<br />

28

Issue 2: Standard <strong>of</strong> Pro<strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> correct standard:<br />

- balance <strong>of</strong> probability<br />

- a single standard: a tribunal may be satisfied as to an<br />

evidential matter if it considers, on all the evidence, that it<br />

was more likely than not<br />

- the tribunal must have in mind as a factor – to whatever<br />

extent is appropriate in the particular case – that the more<br />

serious the allegation the less likely it is that the event<br />

occurred and, hence, the stronger should be the evidence<br />

before the tribunal concludes that the matter has been<br />

established on the balance <strong>of</strong> probability (See A Solicitor v.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Law</strong> Society <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong>,, FACV 24/2007).<br />

29<br />

Issue 2: Standard <strong>of</strong> Pro<strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> Committee directed itself on the standard <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong>:<br />

“<strong>The</strong> Defence advocated a higher standard <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong> than ‘a<br />

mere balance <strong>of</strong> probability‘, at least to ‘a high degree <strong>of</strong><br />

probability‘.<br />

This Committee does not want to get involved in legalistic<br />

definition <strong>of</strong> what the two terms mean. What the<br />

Committee can confirm is that it was relied only on the<br />

documentary evidence submitted by the parties and oral<br />

testimony <strong>of</strong> the witnesses. <strong>The</strong> onus <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong> is on the<br />

Assisting Officer to produce evidence to substantiate the<br />

Charges. Where there is no documentary evidence and the<br />

oral evidence by witnesses are in conflict, the benefit will<br />

go the Accused Officer.“<br />

Was the correct standard applied?<br />

30<br />

Issue 2: Standard <strong>of</strong> Pro<strong>of</strong><br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“…that direction, it seems to me…fails to take into<br />

account what any standard <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong> demands; that is, a<br />

review <strong>of</strong> the strength <strong>of</strong> the evidence. Even when there is<br />

no conflict, the evidence simply may not be cogent enough.<br />

It seems to me that certain <strong>of</strong> the core issues that fell for<br />

determination by the Inquiry Committee demanded not only<br />

an accurate assessment <strong>of</strong> what it was that the evidence was<br />

intended to pro<strong>of</strong> but whether understood in context, it was<br />

compelling enough to do so.“<br />

31<br />

Issue 2: Standard <strong>of</strong> Pro<strong>of</strong><br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“…by way illustration only, the Committee may have<br />

directed itself as follows: ‘<strong>The</strong> accused <strong>of</strong>ficer [the<br />

applicant] has a long and unblemished record. He has held<br />

positions <strong>of</strong> considerable responsibility. <strong>The</strong> charges<br />

against him are serious. <strong>The</strong>y allege misconduct on his part<br />

by way <strong>of</strong> a failure to discharge his duties to the standard<br />

expected <strong>of</strong> an <strong>of</strong>ficer <strong>of</strong> his rank. Having regard to his<br />

history <strong>of</strong> service, his alleged misconduct must be<br />

improbable. That being the case, the more compelling must<br />

be the evidence needed to satisfy us on the preponderance<br />

<strong>of</strong> probability that, instead <strong>of</strong> striving to do his best in<br />

circumstances <strong>of</strong> extreme difficulty, the applicant was guilty<br />

<strong>of</strong> oversight and neglect and was therefore guilty <strong>of</strong><br />

misconduct.‘“<br />

32

Issue 3: Denial <strong>of</strong> legal representation<br />

• MR applied to have legal representation in the<br />

disciplinary proceeding.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Secretary for Civil Service refused legal<br />

representation on the basis <strong>of</strong> a policy that legal<br />

representation would only be permitted for<br />

compelling reasons.<br />

• Is this the proper test?<br />

• If the fairness test is applied in this case, should<br />

legal representation be allowed?<br />

Issue 3: Denial <strong>of</strong> legal representation<br />

Public Service (Disciplinary) Regulation s.8(3)<br />

provides that:<br />

“<strong>The</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficer may be assisted in his defence by-<br />

(a) another public servant, other than a legally<br />

qualified <strong>of</strong>ficer, who may be a representative<br />

member <strong>of</strong> a staff association represented on the<br />

Senior Civil Service Council; or<br />

(b) such other person as the Chief Executive may<br />

authorise.“<br />

33<br />

34<br />

Issue 3: Denial <strong>of</strong> legal representation<br />

• Under the Regulation, the CE has the discretion to<br />

authorise representation <strong>of</strong> an <strong>of</strong>ficer by ‘such other<br />

person‘ as the <strong>of</strong>ficer may choose, that ‘other person‘<br />

must include a lawyer. <strong>The</strong>re is a discretion to permit<br />

legal representations if the circumstances were<br />

appropriate. It is a matter, in each and every case, <strong>of</strong><br />

what fairness requires.<br />

• Under common law, there is no absolute right to be<br />

legally represented before an administrative tribunal,<br />

even a tribunal with the power to impose swingeing<br />

penalties, there is a discretion vested in the tribunal to<br />

permit legal representation if fairness requires it.<br />

35<br />

Issue 3: Denial <strong>of</strong> legal representation<br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“I am <strong>of</strong> the view that the approach adopted by the Secretary for the<br />

Civil Service was erroneous. His function was simply to weigh all<br />

the factors relevant to the applicant‘s application and to come to a<br />

judgment as to what fairness required in his case. Instead, it seems<br />

that he approached the matter on the basis that he must adhere to a<br />

policy, seemingly well established, to the effect that legal<br />

representation would not be permitted unless compelling<br />

circumstances were demonstrated. In so doing, the Secretary was<br />

fettering his discretion.<br />

…For him the threshold test was…one <strong>of</strong>…attempting to determine<br />

whether, on consideration <strong>of</strong> all relevant factors, an exception should<br />

be made to the general rule laid down by the policy. But, in my<br />

opinion, what fairness dictates in determining whether legal<br />

representation should or should not be granted is not to be constrained<br />

by the shackles <strong>of</strong> some set policy, still less a policy that puts the bar<br />

as high as the requirement to show compelling circumstances…there<br />

can be no threshold test <strong>of</strong> ‘exceptionality‘. “<br />

36

Issue 3: Denial <strong>of</strong> legal representation<br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“This leads me to consider whether, despite its shortcomings, the<br />

decision made by the Secretary for the Civil Service in fact<br />

prejudiced the applicant in any material way. It is well established<br />

that a breach <strong>of</strong> the rules <strong>of</strong> fairness will not inevitably lead to an<br />

administrative decision being quashed.<br />

…In my judgment, these circumstances created a complex<br />

scenario…the difficulties and the nuances <strong>of</strong> explaining to the<br />

Inquiry Committee the unique problems faced in that situation plainly<br />

required the services <strong>of</strong> a legally qualified advocate trained to<br />

separate out the relevant from the irrelevant and to express in the<br />

clearest manner possible the subtle and complex difficulties that<br />

would have arisen in undertaking the Harbour Fest.<br />

I am satisfied that the decision to deny the applicant legal<br />

representation, having regard to the exceptional circumstances <strong>of</strong> his<br />

case, may well have materially prejudiced him in the presentation <strong>of</strong><br />

his case. In short, the decision denied him natural justice.“<br />

37<br />

Issue 4:<br />

Dual role played by the Department <strong>of</strong> Justice<br />

• DOJ acts as a legal adviser to Government in respect <strong>of</strong> disciplinary<br />

proceedings brought against civil servants guilty <strong>of</strong> misconduct.<br />

• A law <strong>of</strong>ficer in the DOJ gave advice concerning the prosecution:<br />

(a) the institution <strong>of</strong> the disciplinary proceeding (advising whether<br />

there was a prima facie case against the accused <strong>of</strong>ficer;<br />

considering the draft charges, and giving advice concerning the<br />

accused <strong>of</strong>ficer‘s request for legal representation); (b) during the<br />

course <strong>of</strong> the hearings before the Inquiry Committee (giving<br />

advice to those responsible for the prosecution <strong>of</strong> the proceedings);<br />

(c) the report <strong>of</strong> the Inquiry Committee (considering the report to<br />

advise whether the proceedings were in order and whether the<br />

findings <strong>of</strong> the Inquiry Committee were supported by evidence<br />

presented during the hearings.)<br />

• <strong>The</strong> same law <strong>of</strong>ficer gave advice to the Secretary for the Civil<br />

Service (giving advice whether the accused <strong>of</strong>ficer was or was not<br />

guilty <strong>of</strong> any breach <strong>of</strong> discipline and the appropriate penalty to be<br />

given.<br />

• Any apparent bias?<br />

38<br />

Issue 4:<br />

Dual role played by the Department <strong>of</strong> Justice<br />

• Test for apparent bias: “<strong>The</strong> Court must<br />

f i r s t a s c e r t a i n a l l t h e r e l e v a n t<br />

circumstances and then ask whether those<br />

circumstances would lead a fair-minded<br />

and informed observer to conclude there<br />

was a real possibility that the tribunal was<br />

biased.“<br />

Deacons v. White & Case Ltd Liability<br />

Partnership (2003) 6 HKCFAR 322.<br />

39<br />

Issue 4:<br />

Dual role played by the Department <strong>of</strong> Justice<br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“…in my view, there was an inherent conflict in<br />

playing an integral advisory role in the prosecution<br />

<strong>of</strong> the applicant for breach <strong>of</strong> discipline and<br />

thereafter playing an integral role in advising the<br />

Secretary for the Civil Service whether to find the<br />

applicant guilty <strong>of</strong> any such breach.<br />

…a fair-minded and informed observer, having<br />

considered the facts, would have concluded that<br />

there was a real possibility <strong>of</strong> bias on the part <strong>of</strong> Mr<br />

Wingfield arising out <strong>of</strong> his dual advisory role.“<br />

40

Issue 5: Non-disclosure to MR <strong>of</strong> the advice given by<br />

the law <strong>of</strong>ficer to the Secretary for the Civil Service<br />

• <strong>The</strong> advice given to the Secretary for the<br />

Civil Service concerning the findings <strong>of</strong><br />

the Inquiry Committee and the viability <strong>of</strong><br />

those findings by the law <strong>of</strong>ficer was not<br />

disclosed to MR.<br />

• Was this unfair?<br />

41<br />

Issue 5: Non-disclosure to MR <strong>of</strong> the advice given by<br />

the law <strong>of</strong>ficer to the Secretary for the Civil Service<br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“It is now well established, certainly in respect <strong>of</strong> disciplinary<br />

proceedings, that it is unfair for a tribunal to receive evidence<br />

or submissions from one <strong>of</strong> the parties without the other<br />

parties having the opportunity to comment on them.<br />

…In the present case, it must be understood that the ultimate<br />

judge <strong>of</strong> the applicant‘s culpability was the Secretary for the<br />

Civil Service. In that sense, he constituted ‘the tribunal‘.…All<br />

that came before constituted the gathering <strong>of</strong> evidence and the<br />

rendering <strong>of</strong> advice so that the Secretary could make his<br />

decision. As such, in my opinion, it was quite clearly a breach<br />

<strong>of</strong> the rule <strong>of</strong> fairness for the Civil Service Bureau, on the<br />

advice <strong>of</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> Justice, to give advice to the<br />

Secretary concerning the decision to be made by him without<br />

giving the applicant the opportunity to see that advice and, if he<br />

wished, to comment on it.“<br />

42<br />

Issue 6: Unreasonableness <strong>of</strong> the findings <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Inquiry Committee<br />

• Charge (a): MR had failed to ensure that the budget<br />

proposed by AmCham for Harbour Fest had been<br />

critically examined by Invest HK and whether the ERWG<br />

had been fully and adequately advised on the proposed<br />

budget when funding approval was considered at the<br />

meeting <strong>of</strong> the ERWG.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Inquiry Committee found that the charge was<br />

substantiated.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Inquiry Committee found that the talent costs, TV<br />

production costs and marketing costs had not been<br />

subject to critical examination by Invest HK.<br />

• <strong>The</strong>re was unchallenged evidence that the budget was<br />

understood to be indicative and that those costs that were<br />

capable <strong>of</strong> verification had been verified.<br />

• Were the decisions on the findings <strong>of</strong> the Inquiry<br />

Committee unreasonable?<br />

43<br />

Issue 6: Unreasonableness <strong>of</strong> the findings <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Inquiry Committee<br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“It is not for the court to examine the merits <strong>of</strong> the Inquiry<br />

Committee‘s findings. This court‘s jurisdiction is restricted<br />

to a review <strong>of</strong> the lawfulness <strong>of</strong> the decision-making<br />

process.<br />

I confess to having considerable sympathy for the<br />

applicant‘s contention: what could be verified was<br />

verified…<br />

<strong>The</strong>re may not have been direct evidence <strong>of</strong> the<br />

consequences <strong>of</strong> any failure – if it be such – on the part <strong>of</strong><br />

the applicant. But the Committee was entitled to consider<br />

all the relevant circumstances at the time and to come to a<br />

finding as to the standard <strong>of</strong> performance to be expected <strong>of</strong><br />

an <strong>of</strong>ficer <strong>of</strong> the applicant‘s rank and experience. This court<br />

must be slow to interfere with a judgment to that end.“<br />

44

Issue 6: Unreasonableness <strong>of</strong> the findings <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Inquiry Committee<br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“It is to be remembered that ‘misconduct‘, as it is defined<br />

in the Disciplinary Guide, is a broad concept, one that can<br />

best be understood by civil servants who are bound by that<br />

concept.<br />

Was the decision nevertheless irrational? Another Inquiry<br />

Committee may well have come to a different conclusion –<br />

I may have done so – but that is not to the point. In my<br />

judgment, whether the determination was right or wrong,<br />

I do not see how it can be described as a decision which<br />

no reasonable Inquiry Committee could have reached.“<br />

45<br />

Issue 7: Chief Executive acting ultra vires in<br />

delegating his powers<br />

• MR made his representations to the Chief Executive as<br />

appeal against the decision <strong>of</strong> the Secretary for the Civil<br />

Service under s.20 <strong>of</strong> the Public Service<br />

(Administration) Order.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Chief Executive delegated to the Chief Secretary<br />

the authority to determine MR‘s appeal.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Chief Secretary, having carefully considered the<br />

case, had decided to uphold the findings as to culpability<br />

and penalty.<br />

• Had the CE acted ultra vire by delegating his power to<br />

consider MR‘s appeal?<br />

46<br />

Issue 7: Chief Executive acting ultra vires in<br />

delegating his powers<br />

Section 20, Public Service (Administration) Order:<br />

(1) Every <strong>of</strong>ficer who has any representations <strong>of</strong> a public or<br />

private nature to make to the Government <strong>of</strong> HKSAR<br />

should address them to the Chief Executive. <strong>The</strong> Chief<br />

Executive shall consider and act upon each representation<br />

as public expediency and justice to the individual may<br />

request.<br />

(2) <strong>The</strong> Chief Executive may appoint a review board to<br />

advise him on such representations addressed to him<br />

relating to appointment, dismissal and discipline <strong>of</strong> public<br />

servants as he things fit.“<br />

Issue 7: Chief Executive acting ultra vires in<br />

delegating his powers<br />

Section 19, Public Service (Administration) Order:<br />

“(1) Subject to subsection (2), the Chief Executive may<br />

delegate to any public servant or any other public <strong>of</strong>ficer<br />

any powers or duties conferred or imposed on him by<br />

sections 3 and 9 to 18.<br />

(2)<strong>The</strong> Chief Executive shall not delegate the power to<br />

make regulations under section 21(2).“<br />

47<br />

48

Issue 7: Chief Executive acting ultra vires in<br />

delegating his powers<br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“As to the powers <strong>of</strong> delegation given to the Chief<br />

Executive under s.63 <strong>of</strong> the Interpretation and General<br />

Clauses Ordinance, Cap. 1, it was not disputed that this<br />

section relates only to delegation <strong>of</strong> statutory powers and<br />

was not therefore relevant to the delegation <strong>of</strong> power under<br />

an executive order.<br />

In reading the relevant provisions <strong>of</strong> the Administration<br />

Order in context, and giving to those provisions their<br />

ordinary English meaning, I confess that I have<br />

considerable difficulty with [the] contention that the power<br />

to delegate powers and functions under s.20 is implicit.“<br />

49<br />

Issue 7: Chief Executive acting ultra vires in<br />

delegating his powers<br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“S.19(1) provides that the Chief Executive‘s power to delegate<br />

is limited to certain specifically identified sections. If the Chief<br />

Executive‘s powers and functions under s.20 were always<br />

‘understood‘ to be subject to delegation, why was s.20 not<br />

included as a relevant section in s.19(1)? On any ordinary<br />

reading, its omission, it seems to me, must have been intended.<br />

…what is sought to be delegated is not an ancillary or<br />

peripheral power, one that is incidental. What is sought to be<br />

delegated is the power to determine appeals by civil servants…<br />

the power relates to matters <strong>of</strong> discipline which can carry<br />

consequences <strong>of</strong> real seriousness.“<br />

50<br />

Issue 7: Chief Executive acting ultra vires in<br />

delegating his powers<br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“It is a power therefore <strong>of</strong> importance. To the extent that<br />

the power goes to the determination <strong>of</strong> disciplinary appeals,<br />

it is a power which has many <strong>of</strong> the features <strong>of</strong> a judicial<br />

power.<br />

I must conclude that the Chief Executive acted outside <strong>of</strong><br />

the powers given to him in the Administration Order when<br />

he purported to delegate the determination <strong>of</strong> the<br />

applicant‘s s.20 appeal. <strong>The</strong> delegation being invalid, so<br />

too was the Chief Secretary‘s decision made pursuant to<br />

that delegation.“<br />

Issue 8: failure <strong>of</strong> CS to give reasons<br />

rejecting MR‘s appeal<br />

• <strong>The</strong> decision <strong>of</strong> the Chief Secretary that MR‘s appeal<br />

should be dismissed was conveyed to MR by a letter. No<br />

reasons for the decision were given.<br />

• MR sought reasons but was refused.<br />

• Was there a duty to give reason by the Chief Secretary?<br />

51<br />

52

Issue 8: failure <strong>of</strong> CS to give reasons<br />

rejecting MR‘s appeal<br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“s. 20 does not impose a statutory duty to give reason.<br />

As to the common law position…this is not to say that there now<br />

exists any rule <strong>of</strong> common law to the effect that a public authority<br />

must always give reasons for its decisions. Nor, as I understand it,<br />

does there exist a duty generally to give reasons subject only to<br />

reasonable exceptions that have evolved by way <strong>of</strong> empirical<br />

experience.<br />

… what will be implied by our courts is only so much as is necessary<br />

by way <strong>of</strong> procedural safeguards to ensure fairness. But the standards<br />

<strong>of</strong> fairness are not.<br />

In the light <strong>of</strong> those principles,…it was necessary in each case to<br />

conduct an analysis <strong>of</strong> “the character <strong>of</strong> the decision making body,<br />

the kind <strong>of</strong> decision it has to make and the statutory or other<br />

framework in which it operates.“<br />

53<br />

Issue 8: failure <strong>of</strong> CS to give reasons<br />

rejecting MR‘s appeal<br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“I am satisfied that the Chief Secretary had no duty in law to give<br />

reasons in the present case. I say so for the following reasons:<br />

(i) As I have said, s.20 <strong>of</strong> the Administration Order imposes no<br />

general duty to give reasons.<br />

(ii) <strong>The</strong> appeal was not to an outside body; for example, to a<br />

division <strong>of</strong> the High Court, which, as a stranger to the<br />

disciplinary code contained in the Administration Order, may be<br />

expected to give reasons to explain its approach. <strong>The</strong> appeal<br />

remained within the Civil Service.<br />

(iii) <strong>The</strong> Chief Secretary did not assume any form <strong>of</strong> inquisitorial<br />

role. <strong>The</strong> Inquiry Committee had already heard the relevant<br />

evidence, made its findings <strong>of</strong> fact and submitted a detailed<br />

report. <strong>The</strong> Chief Secretary was required to do no more than<br />

review the contents <strong>of</strong> the report and the applicant‘s<br />

representations and to assess them in light <strong>of</strong> his own<br />

knowledge and experience as a civil servant.“<br />

54<br />

Issue 8: failure <strong>of</strong> CS to give reasons<br />

rejecting MR‘s appeal<br />

Hartmann J.:<br />

“(iv) <strong>The</strong>re was no appeal to any higher body and no need therefore<br />

to supply reasons for the benefit <strong>of</strong> that body…what must be<br />

remembered is that the entire process is administrative. <strong>The</strong><br />

Chief Secretary is not a judge.<br />

(v) Reasons may be required in a case when the interest at issue is<br />

highly regarded by the law; for example, when the issue is<br />

dismissed from service. In the present case, however, no such<br />

punishment was at risk on appeal. <strong>The</strong> penalty imposed on the<br />

applicant, while obviously a blow for him personally, did not<br />

threaten his continued service at his attained rank.<br />

(vi) …there may be occasions when, for example, a first instance<br />

decision on its face is so aberrant that any review <strong>of</strong> such a<br />

decision demands communicated reasoning. But…I do not see<br />

that, on its face, any finding <strong>of</strong> the Inquiry Committee was so<br />

aberrant as to demand some explanation for its acceptance.“<br />

Applicability <strong>of</strong><br />

Natural Justice<br />

55<br />

56

Ridge v. Baldwin [1964] A. C. 40<br />

57<br />

Ridge v. Baldwin [1964] A. C. 40<br />

• Ridge, became chief constable <strong>of</strong> the County Borough <strong>of</strong> Brighton<br />

in 1956, after serving in the Brighton Police Force for some 33<br />

years.<br />

• Ridge had been arrested on October 25, 1957, and subsequently<br />

tried on a charge <strong>of</strong> conspiring with the senior members <strong>of</strong> his<br />

force and others to obstruct the course <strong>of</strong> justice, and had been<br />

suspended from duty on October 26.<br />

• He was acquitted on February 28 but the other two members <strong>of</strong> the<br />

force were convicted and in sentencing them the trial judge,<br />

Donovan J., made a statement which included grave reflections on<br />

Ridge‘s conduct.<br />

• At a meeting <strong>of</strong> the watch committee, the police authority, on<br />

March 7, 1958, it was resolved that he should be dismissed. <strong>The</strong><br />

watching committee gave no notice to Ridge <strong>of</strong> the grounds on<br />

which the committee proposed to act and no opportunity to hear<br />

Ridge‘s own defence was <strong>of</strong>fered.<br />

58<br />

Ridge v. Baldwin [1964] A. C. 40<br />

• <strong>The</strong> power <strong>of</strong> dismissal is contained in section 191 (4) <strong>of</strong><br />

the Municipal Corporations Act, 1882:<br />

“<strong>The</strong> watch committee, or any two justices having<br />

jurisdiction in the borough, may at any time suspend, and<br />

the watch committee may at any time dismiss, any<br />

borough constable whom they think negligent in the<br />

discharge <strong>of</strong> his duty, or otherwise unfit for the same.“<br />

• Should the principle <strong>of</strong> natural justice be applicable in<br />

this case?<br />

• Was there a breach <strong>of</strong> the rule <strong>of</strong> fair hearing?<br />

59<br />

Ridge v. Baldwin [1964] A. C. 40<br />

Lord Reid:<br />

“…cases <strong>of</strong> dismissal. <strong>The</strong>se appear to fall into three classes:<br />

dismissal <strong>of</strong> a servant by his master, dismissal from an <strong>of</strong>fice held<br />

during pleasure, and dismissal from an <strong>of</strong>fice where there must be<br />

something against a man to warrant his dismissal.<br />

<strong>The</strong> law regarding master and servant is not in doubt. <strong>The</strong>re cannot<br />

be specific performance <strong>of</strong> a contract <strong>of</strong> service and the master can<br />

terminate the contract with his servant at any time and for any reason<br />

or for none. But if he does so in a manner not warranted by the<br />

contract he must pay damages for breach <strong>of</strong> contract.<br />

…<strong>The</strong>n there are many cases where a man holds an <strong>of</strong>fice at<br />

pleasure. …It has always been held, I think rightly, that such an<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficer has no right to be heard before he is dismissed and the reason<br />

is clear. As the person having the power <strong>of</strong> dismissal need not have<br />

anything against the <strong>of</strong>ficer, he need not give any reason.<br />

…the third class which includes the present case. <strong>The</strong>re I find an<br />

unbroken line <strong>of</strong> authority to the effect that an <strong>of</strong>ficer cannot lawfully<br />

be dismissed without first telling him what is alleged against him<br />

and hearing his defence or explanation.“<br />

60

Ridge v. Baldwin [1964] A. C. 40<br />

Lord Reid:<br />

“<strong>The</strong> matter has been further complicated by what I believe to be a<br />

misunderstanding <strong>of</strong> a much-quoted passage in the judgment <strong>of</strong> Atkin L.J.<br />

in Rex v. Electricity Commissioners Ex parte London Electricity Joint<br />

Committee Co.( [1924] 1 K.B. 171, 205; 39 T.L.R. 715) He said:<br />

‘... the operation <strong>of</strong> the writs [<strong>of</strong> prohibition and certiorari] has extended to<br />

control the proceedings <strong>of</strong> bodies which do not claim to be, and would not<br />

be recognised as, Courts <strong>of</strong> Justice. Wherever any body <strong>of</strong> persons having<br />

legal authority to determine questions affecting the rights <strong>of</strong> subjects, and<br />

having the duty to act judicially, act in excess <strong>of</strong> their legal authority, they<br />

are subject to the controlling jurisdiction <strong>of</strong> the King‘s Bench Division<br />

exercised in these writs.‘<br />

If …it is never enough that a body simply has a duty to determine what the<br />

rights <strong>of</strong> an individual should be, but that there must always be something<br />

more to impose on it a duty to act judicially before it can be found to<br />

observe the principles <strong>of</strong> natural justice, then that appears to me impossible<br />

to reconcile with the earlier authorities.<br />

I can see nothing ‘superadded‘ to the duty itself. Certainly Lord Atkin did<br />

not say that anything was superadded. And a later passage in his judgment<br />

convinces me that he, inferred the judicial character <strong>of</strong> the duty from the<br />

nature <strong>of</strong> the duty itself.“<br />

61<br />

Nature <strong>of</strong><br />

decision maker<br />

Nature <strong>of</strong> the<br />

interest <strong>of</strong> the<br />

person affected<br />

62<br />

Kinds <strong>of</strong> Interest<br />

traditional legal rights<br />

63<br />

64

Cooper v. <strong>The</strong> Board <strong>of</strong> Works for the Wandsworth<br />

District (1893) 14 CBNS 180<br />

65<br />

Cooper v. <strong>The</strong> Board <strong>of</strong> Works for the Wandsworth<br />

District (1893) 14 CBNS 180<br />

• Under the s. 76 <strong>of</strong> the Metropolis Local Management Act,<br />

any person shall give seven days‘ notice to the district<br />

board <strong>of</strong> his intention to build before he begins to build a<br />

new house.<br />

• In default <strong>of</strong> such notice it shall be lawful for the district<br />

board to demolish the house.<br />

• C built his house without giving such notice and the<br />

Wandsworth district board decided to pull down and<br />

demolish his house.<br />

• Should the principles <strong>of</strong> natural justice be applicable in<br />

this case?<br />

• Did the Wandsworth district board have the power to<br />

demolish the house without giving any notice to C and<br />

<strong>of</strong>fering him an opportunity <strong>of</strong> being heard?<br />

66<br />

Cooper v. <strong>The</strong> Board <strong>of</strong> Works for the Wandsworth<br />

District (1893) 14 CBNS 180<br />

WILLES, J.<br />

“I apprehend that a tribunal which is by law invested<br />

with power to affect the property <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> Her<br />

Majesty‘s subjects, is bound to give such subject an<br />

opportunity <strong>of</strong> being heard before it proceeds: and<br />

that that rule is <strong>of</strong> universal application, and founded<br />

upon the plainest principles <strong>of</strong> justice.“<br />

Lau Tak-pui v. Immigration Tribunal<br />

[1992] 1 HKLR 374<br />

67<br />

68

Lau Tak-pui v. Immigration Tribunal<br />

[1992] 1 HKLR 374<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Immigration Tribunal established under the Immigration<br />

Ordinance in exercising its power under s. 53D <strong>of</strong> the Ordinance<br />

determined that Lau had not been born in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong>, that the<br />

removal order made by the Deputy Director <strong>of</strong> Immigration was<br />

therefore valid and that his appeal against such orders should be<br />

dismissed.<br />

• <strong>The</strong>re is no express provision requiring the Tribunal to give reason.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Tribunal did make a statement explaining the ground for its<br />

decision as follows:<br />

“After careful consideration <strong>of</strong> the evidence given by all parties<br />

concerned and by the witnesses presented, the Tribunal has come<br />

to the conclusion that the Appellants, have not discharged the<br />

burden <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong> that they were born in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> and therefore do<br />

not enjoy the right <strong>of</strong> abode in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> under s. 2A <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Immigration Ordinance. <strong>The</strong> appeal is dismissed.“<br />

• Should the principles <strong>of</strong> natural justice be applicable in this<br />

case?<br />

• Was there a duty to give reason?<br />

• Was that reason an adequate one?<br />

69<br />

Lau Tak-pui v. Immigration Tribunal<br />

[1992] 1 HKLR 374<br />

Decision <strong>of</strong> the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal:<br />

“<strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> Immigration Tribunal was and is a fully judicial and<br />

non-domestic body when hearing such appeals … it exercises powers<br />

affecting the liberty and residential and citizenship rights <strong>of</strong><br />

appellants pursuant to statutory provisions <strong>of</strong> some complexity. <strong>The</strong>se<br />

are special circumstances which, quite apart from any implication to<br />

be derived from the wording <strong>of</strong> s. 53D, as to which I express no<br />

opinion, require as a matter <strong>of</strong> fairness the provision <strong>of</strong> outline<br />

reasons showing to what issues the Tribunal has directed its mind and<br />

the evidence upon which it has based its conclusions.<br />

Turning then to the adequacy <strong>of</strong> the reasons given in the respective<br />

appeals they show that the only issue …fell for their determination,<br />

namely the appellants‘ places <strong>of</strong> birth, had been addressed and, by<br />

necessary implication, that all the evidence germane to that issue had<br />

been considered.“<br />

70<br />

O‘Reilly v. Mackman [1983] 2 A.C. 237<br />

public law interests<br />

71<br />

72

O‘Reilly v. Mackman [1983] 2 A.C. 237<br />

• O‘Reilly was serving a long sentence <strong>of</strong> imprisonment.<br />

A disciplinary award <strong>of</strong> forfeiture <strong>of</strong> remission <strong>of</strong><br />

sentence was made by the Board <strong>of</strong> Visitors <strong>of</strong> Hull<br />

Prison in the exercise <strong>of</strong> their disciplinary jurisdiction<br />

against O‘Reilly.<br />

• O‘Reilly wanted to challenge the decision on the ground<br />

that the Board failed to observe the rules <strong>of</strong> natural<br />

justice.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> action was commenced by originating summons,<br />

i.e. by private law proceeding.<br />

• Should the principles <strong>of</strong> natural justice be applicable<br />

in this case?<br />

• Was the matter a public law or a private law matter?<br />

• Can public law matter be proceeded in private law<br />

proceeding?<br />

73<br />

O‘Reilly v. Mackman [1983] 2 A.C. 237<br />

Lord Diplock:<br />

“It is not…contended that the decision <strong>of</strong> the board<br />

awarding him forfeiture <strong>of</strong> remission had infringed or<br />

threatened to infringe any right <strong>of</strong> the appellant derived<br />

from private law, whether a common law right or one<br />

created by a statute. Under the Prison Rules remission <strong>of</strong><br />

sentence is not a matter <strong>of</strong> right but <strong>of</strong> indulgence. So far as<br />

private law is concerned all that each appellant had was a<br />

legitimate expectation, based upon his knowledge <strong>of</strong> what is<br />

the general practice, that he would be granted the maximum<br />

remission, permitted by …the Prison Rules, <strong>of</strong> one third <strong>of</strong><br />

his sentence if by that time no disciplinary award <strong>of</strong><br />

forfeiture <strong>of</strong> remission had been made against him. So the<br />

second thing to be noted is that none <strong>of</strong> the appellants had<br />

any remedy in private law.“<br />

74<br />

O‘Reilly v. Mackman [1983] 2 A.C. 237<br />

McInnes v Onslow-Fane [1978] 1 WLR 1520<br />

Lord Diplock:<br />

“In public law, as distinguished from private law, however, such<br />

legitimate expectation gave to each appellant a sufficient interest to<br />

challenge the legality <strong>of</strong> the adverse disciplinary award made against<br />

him by the board on the ground that in one way or another the board<br />

in reaching its decision had acted outwith the powers conferred upon<br />

it by the legislation under which it was acting; and such grounds<br />

would include the board‘s failure to observe the rules <strong>of</strong> natural<br />

justice: which means no more than to act <strong>fairly</strong> towards him in<br />

carrying out their decision-making process, and I prefer so to put it.<br />

In the instant cases where the only relief sought is a declaration <strong>of</strong><br />

nullity <strong>of</strong> the decisions <strong>of</strong> a statutory tribunal, the Board <strong>of</strong> Visitors <strong>of</strong><br />

Hull Prison, as in any other case in which a similar declaration <strong>of</strong><br />

nullity in public law is the only relief claimed, I have no hesitation, in<br />

agreement with the Court <strong>of</strong> Appeal, in holding that to allow the<br />

actions to proceed would be an abuse <strong>of</strong> the process <strong>of</strong> the court.“<br />

75<br />

76

McInnes v Onslow-Fane [1978] 1 WLR 1520<br />

• M applied for the licence to the western area council <strong>of</strong><br />

the British Boxing Board <strong>of</strong> Control, and the board<br />

refused to grant it. <strong>The</strong> board was an unincorporated body<br />

<strong>of</strong> persons formed with the objects <strong>of</strong> controlling,<br />

regulating and encouraging pr<strong>of</strong>essional boxing in the<br />

United Kingdom.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> board did not inform M the reason for the decision<br />

nor did the board agree to give him an oral hearing.<br />

• Should the principles <strong>of</strong> natural justice be applicable in<br />

this case?<br />

• Was there a breach <strong>of</strong> the principles <strong>of</strong> natural justice?<br />

77<br />

McInnes v Onslow-Fane [1978] 1 WLR 1520<br />

Megarry V.-C.:<br />

“…there is the question <strong>of</strong> whether the grant or refusal <strong>of</strong> a licence<br />

by the board is subject to any requirements <strong>of</strong> natural justice or<br />

fairness which will be enforced by the courts.<br />

…at least three categories may be discerned. First, there are what may<br />

be called the forfeiture cases. In these, there is a decision which takes<br />

away some existing right or position, as where a member <strong>of</strong> an<br />

organisation is expelled or a licence is revoked. Second, at the other<br />

extreme there are what may be called the application cases. <strong>The</strong>se are<br />

cases where the decision merely refuses to grant the applicant the<br />

right or position that he seeks, such as membership <strong>of</strong> the<br />

organisation, or a licence to do certain acts. Third, there is an<br />

intermediate category, which may be called the expectation cases,<br />

which differ from the application cases only in that the applicant has<br />

some legitimate expectation from what has already happened that his<br />

application will be granted. This head includes cases where an<br />

existing licence-holder applies for a renewal <strong>of</strong> his licence or a<br />

person already elected or appointed to some position seeks<br />

confirmation from some confirming authority.“<br />

78<br />

McInnes v Onslow-Fane [1978] 1 WLR 1520<br />

Megarry V.-C.:<br />

“It seems plain that there is a substantial distinction between the<br />

forfeiture cases and the application cases. In the forfeiture cases, there is<br />

a threat to take something away for some reason: and in such cases, the<br />

right to an unbiased tribunal, the right to notice <strong>of</strong> the charges and the<br />

right to be heard in answer to the charges…are plainly apt. In the<br />

application cases, on the other hand, nothing is being taken away, and in<br />

all normal circumstances there are no charges, and so no requirement <strong>of</strong><br />

an opportunity <strong>of</strong> being heard in answer to the charges. Instead, there is<br />

the far wider and less defined question <strong>of</strong> the general suitability <strong>of</strong> the<br />

applicant for membership or a licence. <strong>The</strong> distinction is well-recognised,<br />

for in general it is clear that the courts will require natural justice to be<br />

observed for expulsion from a social club, but not on an application for<br />

admission to it. <strong>The</strong> intermediate category, that <strong>of</strong> the expectation cases,<br />

may at least in some respects be regarded as being more akin to the<br />

forfeiture cases than the application cases; for although in form there is<br />

no forfeiture but merely an attempt at acquisition that fails, the legitimate<br />

expectation <strong>of</strong> a renewal <strong>of</strong> the licence or confirmation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

membership is one which raises the question <strong>of</strong> what it is that has<br />

happened to make the applicant unsuitable for the membership or licence<br />

for which he was previously thought suitable.“<br />

79<br />

McInnes v Onslow-Fane [1978] 1 WLR 1520<br />

Megarry V.-C.:<br />

“...there may well be jurisprudential questions about the true<br />

nature <strong>of</strong> such a ‘right.‘ I have no intention <strong>of</strong> discussing the<br />

wide variety <strong>of</strong> meanings which the protean word ‘right‘<br />

embraces; but if a person has a right in the strict sense <strong>of</strong> the<br />

word, then some other person or persons must be subject<br />

to a duty correlative to that right. Yet who is under a duty<br />

to provide the work? Who can be sued? <strong>The</strong> ‘right to work‘<br />

can hardly mean that a man has a ‘right‘ to work at<br />

whatever employment he chooses, however unsuitable he is<br />

for it; and if his ‘right‘ is merely to have some work<br />

provided for him that is within his capabilities, then the<br />

difficulty <strong>of</strong> determining who is under the duty to provide it<br />

is increased.<br />

…‘the right to work‘ …will not come to be accepted by the<br />

law as being a term <strong>of</strong> art, or as an example <strong>of</strong> what can<br />

truly be called a ‘right.‘“<br />

80

McInnes v Onslow-Fane [1978] 1 WLR 1520<br />

Megarry V.-C.:<br />

“Looking at the case as whole, in my judgment there is no obligation<br />

on the board to give the plaintiff even the gist <strong>of</strong> the reasons why<br />

they refused his application, or proposed to do so. This is not a case in<br />

which there has been any suggestion <strong>of</strong> the board considering any<br />

alleged dishonesty or morally culpable conduct <strong>of</strong> the plaintiff.<br />

…<strong>The</strong>re is a more general consideration. I think that the courts must<br />

be slow to allow any implied obligation to be fair to be used as a<br />

means <strong>of</strong> bringing before the courts for review honest decisions <strong>of</strong><br />

bodies exercising jurisdiction over sporting and other activities which<br />

those bodies are far better fitted to judge than the courts. This is so<br />

even where those bodies are concerned with the means <strong>of</strong> livelihood<br />

<strong>of</strong> those who take part in those activities.<br />

…I cannot see how the obligation to be fair can be said in a case <strong>of</strong><br />

this type to require a hearing. I do not see why the board should not be<br />

fully capable <strong>of</strong> dealing <strong>fairly</strong> with the plaintiff‘s application without<br />

any hearing. <strong>The</strong> case is not an expulsion case where natural justice<br />

confers the right to know the charge and to have an opportunity <strong>of</strong><br />

meeting it at a hearing.“<br />

81<br />

Ridge v. Baldwin [1964] A. C. 40<br />

Lord Reid:<br />

“…cases <strong>of</strong> dismissal. <strong>The</strong>se appear to fall into three classes:<br />

dismissal <strong>of</strong> a servant by his master, dismissal from an <strong>of</strong>fice held<br />

during pleasure, and dismissal from an <strong>of</strong>fice where there must be<br />

something against a man to warrant his dismissal.<br />

<strong>The</strong> law regarding master and servant is not in doubt. <strong>The</strong>re cannot<br />

be specific performance <strong>of</strong> a contract <strong>of</strong> service and the master can<br />

terminate the contract with his servant at any time and for any reason<br />

or for none. But if he does so in a manner not warranted by the<br />

contract he must pay damages for breach <strong>of</strong> contract.<br />

…<strong>The</strong>n there are many cases where a man holds an <strong>of</strong>fice at<br />

pleasure. …It has always been held, I think rightly, that such an<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficer has no right to be heard before he is dismissed and the reason<br />

is clear. As the person having the power <strong>of</strong> dismissal need not have<br />

anything against the <strong>of</strong>ficer, he need not give any reason.<br />

…the third class which includes the present case. <strong>The</strong>re I find an<br />

unbroken line <strong>of</strong> authority to the effect that an <strong>of</strong>ficer cannot lawfully<br />

be dismissed without first telling him what is alleged against him<br />

and hearing his defence or explanation.“<br />

82<br />

Mohamed Yaqub Khan v. Attorney General<br />

[1986] HKLR 922<br />

Mohamed Yaqub Khan v. Attorney General<br />

[1986] HKLR 922<br />

• Khan, a Superintendent <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> Auxiliary<br />

Police Force, was dismissed by the Commissioner <strong>of</strong><br />

Police on the ground <strong>of</strong> his misconduct.<br />

• Section 9(1) <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> Auxiliary Police Force<br />

Ordinance (Cap. 233), was in these terms:<br />

“Gazetted <strong>of</strong>ficers may be appointed, promoted,<br />

reduced in rank or dismissed by the Governor.“<br />

• Khan was not informed <strong>of</strong> the actual allegations against<br />

him.<br />

• Should the principles <strong>of</strong> natural justice be applicable<br />

in this case<br />

83<br />

84

Mohamed Yaqub Khan v. Attorney General<br />

[1986] HKLR 922<br />

Cons, V.-P.:<br />

“…in cases where an <strong>of</strong>ficer can only be dismissed for<br />

cause…the requirements <strong>of</strong> natural justice will depend<br />

upon the reason which in fact underlies his dismissed. At<br />

the very least, we would think he is entitled to know the<br />

reason for his dismissal.<br />

…we have come to the conclusion …to dismiss Mr. Khan<br />

were matters <strong>of</strong> misconduct…we therefore conclude that in<br />

the circumstances Mr. Khan ought to have been informed<br />

<strong>of</strong> the contents <strong>of</strong> that memorandum and given the<br />

opportunity to make representations in answer.“<br />

public law interests<br />

include legitimate expectation<br />

(See the lecture on Legitimate<br />

Expectation concerning<br />

situations that can generate a<br />

legitimate expectation)<br />

85<br />

86<br />

Right to Unbiased Decision: <br />

Right to Unbiased Decision <br />

• test <strong>of</strong> bias: no need to have actual bias; only<br />

apparent bias is needed.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> test to determine apparent bias:<br />

Reasonable likelihood to the eyes <strong>of</strong> reasonable<br />

man<br />

a real danger <strong>of</strong> bias on the part <strong>of</strong> the relevant<br />

members <strong>of</strong> the tribunal in question<br />

87<br />

88

Right to Unbiased Decision: <br />

• Test for apparent bias in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong>: “<strong>The</strong><br />

Court must first ascertain all the relevant<br />

circumstances and then ask whether those<br />

circumstances would lead a fair-minded and<br />

informed observer to conclude there was a real<br />

possibility that the tribunal was biased.“<br />

Deacons v. White & Case Ltd Liability<br />

Partnership (2003) 6 HKCFAR 322.<br />

Right to Unbiased Decision:<br />

Causes <strong>of</strong> prejudice: <br />

• judge in his own cause: automatic<br />

disqualification<br />

– pecuniary interest<br />

– prosecutor as judge<br />

– other interests<br />

89<br />

90<br />

Dimes v. <strong>The</strong> Proprietor <strong>of</strong> the Grand Junction<br />

Canal (1852) 3 H.L.C. 7<br />

Dimes v. <strong>The</strong> Proprietor <strong>of</strong> the Grand Junction<br />

Canal (1852) 3 H.L.C. 7<br />

• A public company, which was incorporated, filed a bill<br />

<strong>of</strong> equity against a land-owner, in a matter largely<br />

involving the interests <strong>of</strong> the company.<br />

• Lord Cottenham, the Lord Chancellor had an interest as<br />

a shareholder in the company to the amount <strong>of</strong> several<br />

thousand pounds, a fact was unknown to the defendant<br />

in the suit.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> cause was heard before the Vice-Chancellor, who<br />

granted the relief sought by the company.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Lord Chancellor, on appeal, affirmed the order <strong>of</strong><br />

the Vice-Chancellor.<br />

• Any Bias?<br />

91<br />

92

Dimes v. <strong>The</strong> Proprietor <strong>of</strong> the Grand Junction<br />

Canal (1852) 3 H.L.C. 7<br />

Lord Campbell:<br />

“No one can suppose that Lord Cottenham could be, in<br />

the remotest degree, influenced by the interest that he had<br />

in this concern; but my Lords, it is <strong>of</strong> the last importance<br />

that he maxim that no man is to be a judge in his own<br />

cause should be held sacred.<br />

…And that is not to be confined to a cause in which he is a<br />

party, but applies to a cause in which he has an interest.<br />

This will be a lesson to all inferior tribunals to take care not<br />

only that in their decrees they are not influenced by their<br />

personal interest, but to avoid the appearance <strong>of</strong> labouring<br />

under such an influence.“<br />

Panel on Takeovers and Mergers and Another v. William<br />

Cheng Kai-man (Privy Council Appeal No. 16 <strong>of</strong> 1995)<br />

93<br />

94<br />

Panel on Takeovers and Mergers and Another v. William<br />

Cheng Kai-man (Privy Council Appeal No. 16 <strong>of</strong> 1995)<br />

• <strong>The</strong> statutory body responsible for regulating the<br />

securities market in <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> is the Securities and<br />

Futures Commission.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> Panel on Takeovers and Mergers<br />

under the Securities and Futures Commission is<br />

responsible for policing the observance <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Hong</strong><br />

<strong>Kong</strong> Takeover Code.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Panel determined that Cheng had acted in breach<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Rule <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Hong</strong> <strong>Kong</strong> Takeover Code in his<br />

takeover <strong>of</strong> the Royle Company.<br />

• <strong>The</strong> Panel‘s ruling required Cheng to pay compensation<br />

to shareholders amounting to some HK$49 million.<br />

95<br />

Panel on Takeovers and Mergers and Another v. William<br />

Cheng Kai-man (Privy Council Appeal No. 16 <strong>of</strong> 1995)<br />

• One <strong>of</strong> the members <strong>of</strong> the Panel, Clark, had sent to the<br />

Chairman <strong>of</strong> the Securities and Futures Commission a letter<br />

concerning Cheng‘s breach <strong>of</strong> the Code in these terms:<br />

“I am writing to you in my assumed capacity as the keeper <strong>of</strong> the conscience<br />