The London Globalist - Issue 1

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

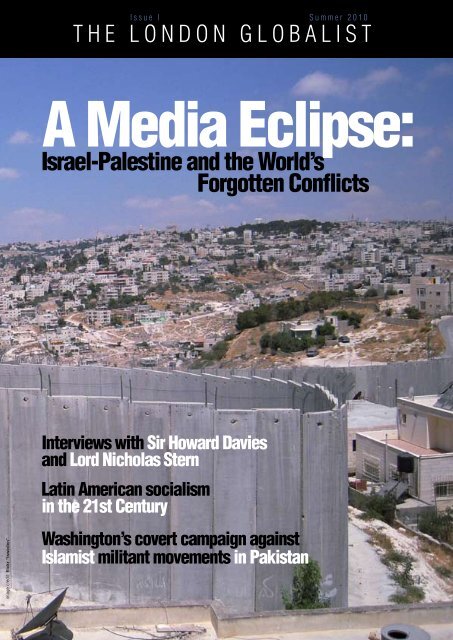

<strong>Issue</strong> I Summer 2010<br />

THE LONDON GLOBALIST<br />

A Media Eclipse:<br />

Israel-Palestine and the World’s<br />

Forgotten Conflicts<br />

image credit: flickr “tsweden”<br />

Interviews with Sir Howard Davies<br />

and Lord Nicholas Stern<br />

Latin American socialism<br />

in the 21st Century<br />

Washington’s covert campaign against<br />

Islamist militant movements in Pakistan

<strong>The</strong> <strong>London</strong> <strong>Globalist</strong> is a member of<br />

Global21<br />

Network of International<br />

Affairs Magazines<br />

www.global21online.org<br />

1 NETWORK<br />

LINKING<br />

FUTURE<br />

WORLD<br />

LEADERS<br />

5 LANGUAGES<br />

5 CONTINENTS<br />

10 UNIVERSITIES<br />

245 000 STUDENTS<br />

Yale University • University of Toronto • University of Sydney • Hebrew University • Institut d’Études Politiques de Paris •<br />

<strong>London</strong> School of Economics • Peking University • University of Cape Town • Bogaziçi University • University of South Australia

<strong>The</strong> <strong>London</strong> <strong>Globalist</strong>: <strong>Issue</strong> I Summer 2010<br />

Contents<br />

5 Editorial<br />

FEATURE ARTICLE<br />

A Media Eclipse: Israel-Palestine and the World’s Forgotten Conflicts<br />

6<br />

Cry Havoc! And Let Slip the Drones of War...<br />

<strong>The</strong> Great Game Redux<br />

Interview with Lord Nicholas Stern<br />

<strong>The</strong> Right Kind of Financial Education<br />

New Labour and the Death of the Ideas<br />

Credit Crunched - Governing Global Finance<br />

21st Century Socialism<br />

12<br />

16<br />

20<br />

22<br />

23<br />

24<br />

28<br />

HIGHLIGHTS<br />

<strong>The</strong> Fight of Her Life<br />

32<br />

33<br />

34<br />

38<br />

40<br />

<strong>The</strong> Human Cost of War: How Canada is Coping with its Soldiers’ Mental Health <strong>Issue</strong>s<br />

<strong>The</strong> EU and India: Bigger than the sum of their parts?<br />

Enter Asia, Exit the West?<br />

CULTURE<br />

<strong>The</strong> Man Booker Prize

THE LONDON GLOBALIST<br />

Interested<br />

in Working for<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>London</strong><br />

<strong>Globalist</strong>?<br />

<strong>The</strong> editorial team is currently recruting:<br />

WRITERS PHOTOGRAPHERS DESIGNERS<br />

EDITORS NON-EDITORIAL STAFF<br />

Email editor@londonglobalist.og.uk or visit<br />

www.londonglobalist.org.uk for more details

Dear<br />

<strong>Globalist</strong> Readers<br />

W<br />

elcome to the inaugural<br />

issue of <strong>The</strong> <strong>London</strong><br />

<strong>Globalist</strong>, an LSE magazine<br />

devoted international affairs. Written<br />

and compiled by your fellow students,<br />

the magazine will publish tri-annually<br />

featuring LSE’s best authors as well as<br />

international contributors.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>London</strong> <strong>Globalist</strong> is the result<br />

of a journey started in 2000 at Yale<br />

University. Wishing to deliver highquality<br />

student journalism to inspire and<br />

provoke debate among their peers, <strong>The</strong><br />

Yale <strong>Globalist</strong> soon developed into more<br />

than just an independent magazine and<br />

today consists of 10 chapters worldwide.<br />

We are proud to include LSE within<br />

the Global21 and hope to enable our<br />

dynamic and engaged student body to<br />

contribute in global discussion.<br />

In many ways, this magazine is a<br />

response to a demand; voiced not<br />

only by LSE students wishing greater<br />

participation and forum for debate, but<br />

also by the challenges of our times. As<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>London</strong> <strong>Globalist</strong> is launched and<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Globalist</strong> movement celebrates<br />

its 10-year anniversary, the world can<br />

simultaneously look back on the first<br />

decade of the 21st century. Marked by a<br />

rising China, Climate Change, the war<br />

on terror and the global financial crisis,<br />

the <strong>London</strong> <strong>Globalist</strong> dedicates its first<br />

issue to ‘<strong>The</strong> 21st century: A decade<br />

Retrospect”.<br />

This issue looks at some of the events<br />

that have marked the past decade<br />

and will continue to shape our future.<br />

Simon Black explores the implications<br />

of the recent crisis for global financial<br />

governance in a ‘credit crunched’<br />

world. Reporting on the implications of<br />

changing economic forces on classical<br />

domains of high-politics, Joseph Tam<br />

disaffirms myths concerning the rise of<br />

China and a declining West. Balance of<br />

power continues to feature in Brijesh<br />

Khemlani’s commentary of the ‘Great<br />

Game’ between bordering nations<br />

over Afghanistan. <strong>The</strong> role of ideology<br />

in the past decade is covered in Joe<br />

Rowley’s examination of the socialist<br />

phenomenon in Latin-America and Olly<br />

Wiseman’s obituary for ‘New Labour’<br />

in British politics. Hero Austin and<br />

Kimia Pezeshki interview LSE Professor<br />

Nicholas Stern, a major contributor<br />

to the definitive escalation of Climate<br />

Change on the international agenda.<br />

<strong>The</strong> feature article, by Noah Bernstein,<br />

addresses the controversial question of<br />

perceived disproportionate attention<br />

devoted by the media to the Israel-<br />

Palestine Conflict. Distancing himself<br />

from the exhausted pro-Palestine versus<br />

pro-Israel debate, the focus is instead<br />

on implications for other contemporary<br />

but ‘forgotten’ conflicts such as the<br />

one raging in the North-east of the<br />

Democratic Republic of Congo.<br />

With few of the challenges from the<br />

last decade resolved, the 21st century<br />

might not have yet lived up to promises<br />

of a better future envisioned by many,<br />

and although history remains at<br />

best an imperfect tool for predicting<br />

the future- the demand for strong<br />

voices representing our generation is<br />

heightened.<br />

Enjoy,<br />

Elisa Vieira and Henrik Vaaler<br />

(Editor’s-in-Chief, <strong>The</strong> <strong>London</strong> <strong>Globalist</strong>)<br />

THE LONDON GLOBALIST<br />

EDITORIAL STAFF:<br />

Editors in Chief:<br />

Elisa de Denaro Vieira<br />

Henrik Vaaler<br />

Managing Editors:<br />

Marlies Dachler<br />

Ben Sarhangian<br />

Catherine Tsalikis<br />

Associate Editors:<br />

Simon Black<br />

Wilson Chew<br />

Leonor Gonzalez<br />

Vivien Lu<br />

Juha Saarinen<br />

Noah Schwartz<br />

Francesca Washtell<br />

NON-EDITORIAL STAFF:<br />

Publisher/Executive Editor:<br />

Jeremy Smith<br />

Advertising & Sponsors:<br />

Julia Hug<br />

Eleonore Mouy<br />

Production Editor:<br />

Eduard Piel<br />

Webmaster/Online Editor:<br />

Jeremy Smith<br />

Editorial<br />

5

FEATURE ARTICLE<br />

A Media Eclipse:<br />

Israel-Palestine and the World’s<br />

Forgotten Conflicts<br />

Global coverage of world conflicts pales into<br />

insignificance when compared with reporting on<br />

the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.<br />

In a 48-hour period beginning on Christmas Eve 2008 the<br />

Christian fundamentalist Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA)<br />

killed, dismembered and burned at least 200 Congolese<br />

civilians. Soldiers raped women and girls, twisted the heads<br />

off babies, and cut the lips and ears off those they did not<br />

kill. <strong>The</strong>y hacked the rest to death using machetes or axes.<br />

Child soldiers helped abduct other children.<br />

A Media Eclipse: Israel-Palestine and the World’s Forgotten Conflicts<br />

During the same period the Israeli government and Hamas<br />

officials entered the final stages of failing cease-fire talks.<br />

War was on the horizon, but had not yet begun. An errant<br />

Hamas rocket killed two Gazan sisters; otherwise there were<br />

no cross-border casualties.<br />

According to AlertNet’s World Press Tracker, the two-day<br />

Israeli-Palestinian stand-off was reported in the global media<br />

40 times. <strong>The</strong>re were no reports on the LRA massacre in<br />

the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Over the next<br />

three weeks Israel’s incursion into Gaza left 926 Palestinians<br />

and 3 Israeli civilians dead. <strong>The</strong> global media reported these<br />

events 2896 times. In the same period, Joseph Kony’s LRA<br />

killed 865 civilians and abducted 160 children. <strong>The</strong> media<br />

reported these events a total of 20 times.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Western media’s fascination with the Israeli-Palestinian<br />

conflict (IPC) has long<br />

overshadowed death<br />

and oppression in other<br />

parts of the world. Gilad<br />

Shalit and the Qassam<br />

rocket are known to many; the death of 5.9 million in the<br />

eight-nation Second Congo War is not. Recent Israeli and<br />

Palestinian elections were covered worldwide in real-time,<br />

while images of genocide in Rwanda and Sudan did not<br />

surface until it was too late. Countless articles argue media<br />

bias in favour of Israel or the Palestinians, yet few address<br />

the bias towards the conflict itself.<br />

“Countless articles argue media bias in favour of Israel<br />

or the Palestinians, yet few address the bias towards the<br />

conflict itself.”<br />

image credit: flickr “daveblume”<br />

<strong>The</strong> disproportionate media coverage raises several uncomfortable<br />

questions: why were the deaths of Congolese civilians<br />

at the hands of the LRA deemed less newsworthy than, in<br />

the first instance, crumbling cease-fire talks and, later, the<br />

deaths of Palestinian civilians? More generally, why is the<br />

West so consumed by the IPC and what are the consequences<br />

of underreporting other conflicts? Finally, can anything<br />

be done to redress<br />

the media balance so<br />

that the rights of all<br />

humans – regardless of<br />

colour, ethnicity, and<br />

geography – are given equal weight?<br />

<strong>The</strong> Explanation<br />

At first glance, the discrepancy in coverage appears linked to<br />

racism: how else to explain the ‘sins of omission’ in Rwanda<br />

and Sudan? Or the laissez-faire attitude towards Sierra<br />

Leone, Liberia, DRC, and, most recently, the ignored civilian<br />

massacres in Guinea and Nigeria? It is unlikely that the<br />

6<br />

THE LONDON GLOBALIST

international community would remain silent, or only send<br />

an impotent peacekeeping force, if hundreds of thousands<br />

(or even hundreds) of Palestinians and Israelis were being<br />

killed. However, the indifference is not limited to sub-<br />

Saharan Africa: conflicts in Southeast Asia (Philippines,<br />

Thailand), Latin America (Colombia), the Caucasus (Georgia,<br />

Nagorno-Karabakh), the Balkans (Bosnia), and even North<br />

America (Mexico) have been equally ignored. Consequently,<br />

the charge of racism may<br />

be misplaced.<br />

“…while the IPC may be of greater global<br />

interest than the LRA’s activities, the rights of the<br />

865 civilians killed in the DRC are as important as<br />

the 929 civilians killed in the Gaza conflict.”<br />

Instead, a more plausible<br />

explanation is simple selfinterest:<br />

the geopolitical,<br />

ideological, and religious<br />

implications of the IPC threaten global harmony. A sharp<br />

escalation in violence in the IPC could spark a regional if<br />

not global conflict. In contrast, a war between Eritrea and<br />

Ethiopia, regardless of casualties, does not carry the same<br />

threat to international stability. When Jews, Christians,<br />

Muslims, and Baha’i jostle for position in the Holy Land<br />

the religious sensitivities of half the world’s population<br />

are at stake. Conversely, internecine fighting between the<br />

Kikuyu and Luo of Kenya, again regardless of casualties, is<br />

seen as a tribal matter of little consequence to the outside<br />

world. Finally, and perhaps most important, the IPC is<br />

a proxy for a much larger ideological clash between the<br />

West and the Muslim world. Israel is either perceived as a<br />

symbol of Western imperialist power conducive to Western<br />

regional interests – particularly those of the much-reviled<br />

United States – or as a beacon of democracy amongst a sea<br />

of oppression. <strong>The</strong> Palestinians are seen to either represent<br />

the menace of the Arab and Muslim world or as a David<br />

righteously fighting the world’s Goliaths. <strong>The</strong> framing of the<br />

conflict in these ways permits the West to justify its actions<br />

in the Arab and Muslim world and allows Middle Eastern<br />

leaders to deflect attention away from their own repressive<br />

autocratic regimes. <strong>The</strong> Israelis and Palestinians are pawns<br />

in a greater ideological game, one whose every move is<br />

crucial to the national self-interest of every Western, Arab<br />

and Muslim country alike.<br />

It is clear then that the IPC is important and that the global<br />

media have a vested interest, perhaps even an obligation,<br />

to closely monitor the ongoing turmoil. However, while the<br />

conflict itself may be of prime (self-)interest, the human<br />

rights violations that occur in the IPC are of no greater<br />

comparative importance than those that occur elsewhere.<br />

Yet the global media does not make this crucial distinction<br />

and instead conflates the two. For example, while the IPC<br />

may be of greater global interest than the LRA’s activities, the<br />

rights of the 865 civilians killed in the DRC are as important<br />

as the 929 civilians killed in the Gaza conflict. Consequently,<br />

the explanation behind disproportionate media coverage is<br />

in no way a reasonable justification.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Justifications<br />

Still, arguments are made that human rights in the IPC are<br />

distinct from others and need to be prioritized. However,<br />

each attempted justification reveals contradictions when<br />

compared to past and ongoing conflicts.<br />

1. Special Responsibility<br />

One justification for the media’s fixation is that the world,<br />

and the West in particular, bear a unique responsibility for<br />

the IPC as they abetted the creation of a state for a displaced<br />

people by displacing<br />

another. However, if a sense<br />

of post-partition or postcolonial<br />

responsibility is<br />

the justification then what<br />

of Pakistan and India?<br />

Kashmir, another tragic byproduct<br />

of colonial mapmaking, has largely flown under the<br />

Western media radar despite the deaths of 67 000 civilians<br />

since a rebellion broke out in the Himalayan region in<br />

1989. <strong>The</strong> conflict is over a territory twenty times the size<br />

of Israel and the Palestinian territories, involves twice as<br />

many people, and has resulted in ten times as many deaths.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are other post-partition losers – Nigeria, Ethiopia<br />

and Western Sahara, for example – who do not attract the<br />

same media spotlight as the IPC despite heavy civilian<br />

casualties and rampant oppression. If the West feels a moral<br />

obligation towards Palestinians and Israelis, then a similar<br />

obligation should be felt towards the hundreds of millions of<br />

others whose lives were also permanently disrupted due to<br />

historical Western meddling.<br />

2. Democratic Accountability<br />

A second justification for the media’s dogged attention is<br />

that Israel as a democracy is accountable to higher standards<br />

of behaviour – most importantly on human rights. <strong>The</strong>ir<br />

actions deserve magnification, hence the global media<br />

attention. However, if membership in the club of democracies<br />

demands greater accountability through the free press<br />

then Sri Lanka – a democracy of 20 million – should have<br />

featured as heavily in the media during and especially after<br />

its war with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE)<br />

in early 2009. AlertNet’s World Press Tracker points in a<br />

different direction. <strong>The</strong> daily average of global headlines for<br />

the two conflicts during hostilities is severely unbalanced:<br />

image credit: flickr “daveblume”<br />

FEATURE ARTICLE<br />

A Media Eclipse: Israel-Palestine and the World’s Forgotten Conflicts<br />

7

FEATURE ARTICLE<br />

A Media Eclipse: Israel-Palestine and the World’s Forgotten Conflicts<br />

the IPC, on average, received 148 per day; Sri Lanka/LTTE,<br />

on average, 29 per day. <strong>The</strong> contrast is more disturbing<br />

when considering the civilian death toll: hostilities between<br />

January and May of 2009 left 20 000 Sri Lankan civilians<br />

dead. Both cases involved a government force attacking<br />

a terrorist group in areas dense with civilians. Yet the IPC<br />

featured in global media five times more often despite the<br />

death of twenty times more civilians in Sri Lanka.<br />

<strong>The</strong> average number of daily headlines for the two-week period<br />

following the end of hostilities is equally disproportionate:<br />

IPC, 75 per day; Sri Lanka/LTTE, 19 per day, the latter<br />

conflict falling off the media map almost entirely. This is<br />

particularly disturbing as both the Sri Lankan government<br />

and the LTTE stand accused of war crimes. Israel and<br />

Hamas’ alleged war crimes received intense media follow-up<br />

and the UN-sponsored Goldstone inquiry. <strong>The</strong> UN and the<br />

international community condemned the LTTE – accused<br />

of using civilians as human shields – and the Sri Lankan<br />

government – accused of executing unarmed Tamil prisoners<br />

of war and shelling hospitals and schools – but faced little<br />

follow-up scrutiny by the Western media. <strong>The</strong> UN has not<br />

initiated a war crimes probe as of March 10, 2010. In this<br />

instance, democracy did not lead to greater accountability.<br />

image credit: flickr “Austcare-world Humanitarian Aid’s”<br />

3. Extreme Oppression and Suffering<br />

A third justification is that the oppression suffered by the<br />

Palestinians warrants disproportionate media attention.<br />

Indeed, suffering incurred by Palestinians should be exposed<br />

so as to foster change. However, their cause should not<br />

overshadow the plight of the other 35 million refugees and<br />

24.5 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) worldwide.<br />

Millions of Central African refugees who live in constant fear<br />

of rebel and government attack are oppressed. Millions of<br />

Burmese IDPs with little or no freedom, including the right<br />

to leave their country, are oppressed. Yet their plight has been<br />

lost in the tailwinds of the IPC.<br />

<strong>The</strong> IPC involves 4 million Palestinians and 7 million<br />

Israelis – a relatively small combined population compared<br />

to the above-mentioned conflicts. Since 1980, total civilians<br />

deaths in the Sri Lankan conflict have been fifty times that<br />

of the IPC; Kashmir has seen one hundred times more<br />

civilians killed; and the conflict in the DRC has claimed five<br />

thousand times more lives than the IPC. Of course, death<br />

tolls alone are not a barometer of oppression. However,<br />

other indicators can be used to contextualize human<br />

suffering. For example, the UNDP’s Human Development<br />

Index, which measures “health, knowledge, and standard<br />

of living”, ranks the Occupied Palestinian Territories higher<br />

than every sub-Saharan African country, including South<br />

Africa. <strong>The</strong> index places the Palestinians in the ‘High Human<br />

Development’ category for adult literacy rates (93.8%), life<br />

expectancy at birth (73.3%), and malnourished children<br />

(3%). In all categories, the territories ranked higher than<br />

all South Asian and Arab countries, and even outpaced<br />

Brazil, Russia (adult literacy notwithstanding), India, and<br />

China. Even after Israel’s invasion of Gaza, World Health<br />

Organization representative Mahmoud Daher stated that<br />

“It [Gaza] is, of course, crowded and poor, but it is better<br />

off than nearly all of Africa as well as parts of Asia. <strong>The</strong>re<br />

is no acute malnutrition, and infant mortality rates compare<br />

with those in Egypt and Jordan”. Average aggregate GDP<br />

per capita in the Occupied Palestinian Territories ($4 400<br />

in the Gaza Strip, $2 800 in the West Bank) is greater than<br />

80 other countries including Albania, Armenia, Morocco,<br />

Uruguay, Ukraine, Indonesia, and Viet Nam. In a recent<br />

Wall Street Journal article Palestinian President Mahmoud<br />

Abbas said of the Palestinians living in the West Bank: “[W]<br />

e have a good reality. <strong>The</strong> people are living a normal life.”<br />

<strong>The</strong>se inconvenient truths are not intended to diminish the<br />

Palestinian right to freedom of movement and a homeland:<br />

the aim is simply to put the IPC into global perspective and<br />

to promote a more equitable coverage of global suffering.<br />

4. Type of Conflict<br />

A final justification for disproportionate media attention is<br />

that the IPC is an ongoing national liberation movement<br />

(NLM) rather than a civil war. This line of reasoning raises<br />

two problems. First, there exist other ongoing wars of national<br />

liberation involving large-scale death and destruction that<br />

receive little or no media coverage. Second, coming full<br />

circle, the type of conflict cannot be conflated with human<br />

rights violations: individuals are equal under international<br />

8<br />

THE LONDON GLOBALIST

human rights law.<br />

Other NLMs<br />

Tibet is a NLM that has claimed one million lives, many of<br />

them horrifically, since 1959. In pre-Olympic violence in<br />

March of 2008, Chinese police shot dead 140 protesting<br />

Tibetans. <strong>The</strong> events did make global headlines, but<br />

the coverage ended once the Olympics did – despite the<br />

continuation of human rights abuses.<br />

<strong>The</strong> conflict in Chechnya, classified as a NLM by several<br />

groups, has left 60 000 Chechen civilians dead since 1994.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Russians have massacred civilians and assassinated<br />

Chechen politicians, while the Chechens have launched<br />

suicide attacks and sown terror – violence similar to that of<br />

the IPC yet largely unreported.<br />

Western Sahara is a NLM where<br />

the Sahrawi people reject Morocco’s<br />

1974 annexation of the former<br />

Spanish colony. A 2 700 km wall<br />

(the Berm, or Wall of Shame),<br />

constructed by Morocco in the<br />

1980s, divides the country. It<br />

is manned by Moroccan armed<br />

forces, limiting the movement of<br />

the Sahrawi. <strong>The</strong> US, the EU, the<br />

AU, and the UN do not recognize<br />

Morocco’s occupation of Western<br />

Sahara. AlertNet has a record of<br />

3 international headlines for the<br />

conflict during the whole of 2009,<br />

all linked to Sahrawi human rights<br />

activist Aminatou Haidar’s monthlong<br />

hunger strike in a Spanish airport. <strong>The</strong> number of<br />

casualties in the conflict is ‘only’ in the low hundreds, but its<br />

similarities with the IPC – including accusations of human<br />

rights abuses on both sides – demonstrate that NLMs do not<br />

necessarily receive an equal place under the global media<br />

spotlight.<br />

Human Rights Law<br />

Differentiating - and prioritizing – a certain type of conflict<br />

over another ignores the fundamental concept of human<br />

rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human<br />

Rights and the Fourth Geneva Convention: a civilian<br />

oppressed or killed in any part of the world under any<br />

illegal circumstances is a violation of their human rights.<br />

Every individual is entitled to the same protection under<br />

international human rights law, international humanitarian<br />

law, and international criminal law regardless of the intensity<br />

or breadth of the conflict causing their deadly or oppressive<br />

circumstances. This includes the 150 000 Liberians killed<br />

in the civil war of ‘99 – ‘03, the 300 000 North Koreans<br />

starved or worked to death in gulags since 2005, and the<br />

37 000 Kurds killed by Turkish forces since 1984. Yet there<br />

were no protests over Liberia, nor have any UN resolutions<br />

been passed on behalf of the North Koreans, and there have<br />

been no calls for divestment of Turkish assets. None recieved<br />

image credit: flickr “Zoriah”<br />

media coverage proportionate to that of the IPC despite<br />

vastly higher casualty numbers and thoroughly oppressive<br />

conditions. <strong>The</strong> message this conveys to these victims is clear:<br />

their human rights are secondary to the rights of others.<br />

Further, individual victims of human rights abuses who have<br />

no internal mechanism for recourse are more vulnerable<br />

than victims of formal conflicts such as the IPC. For example,<br />

women stoned to death for suspected adultery, men publicly<br />

executed for suspected homosexuality, albinos killed for body<br />

parts, lesbians ‘correctively raped’, or adults and children<br />

used as slaves - these isolated groups can all have their safety<br />

enhanced through increased international media attention.<br />

Yet advocacy on their behalf through the media (and even by<br />

human rights groups) is minimal when compared to the IPC,<br />

leaving them out of sight and, consequently, out of mind.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Consequences<br />

Ultimately, there is no justification for the media’s<br />

preferential coverage of human rights abuses in the IPC.<br />

<strong>The</strong> immediate consequences of this conflict bias are further<br />

polarisation of an already fragile divide and the export of its<br />

inflammatory politics to the rest of the world. An indirect but<br />

equally important consequence is that the media attention<br />

helps the IPC command a disproportionate chunk of global<br />

humanitarian aid, to the detriment of refugees and IDPs<br />

around the globe. Finally, while the IPC is at the forefront of<br />

the public consciousness, dozens of other conflicts involving<br />

hundreds of millions of people are almost entirely ignored.<br />

<strong>The</strong> United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine<br />

Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) provides education,<br />

health care, social services and emergency aid to 400 000<br />

Palestinians. <strong>The</strong>re exists no other UN agency dedicated<br />

solely to refugees from a specific region or conflict. <strong>The</strong><br />

rest of the 60 million refugees and IDPs around the globe<br />

rely on the United Nations High Commission on Refugees<br />

(UNHCR). In 2000, UNRWA spent $72 per Palestinian<br />

while the UNHCR spent $53 on refugees from the rest of the<br />

world, an inexplicable shortfall of 25%. <strong>The</strong> UNRWA claims<br />

it is under funded and makes repeated funding appeals to its<br />

two main donors – the United States and the European union.<br />

FEATURE ARTICLE<br />

A Media Eclipse: Israel-Palestine and the World’s Forgotten Conflicts<br />

THE LONDON GLOBALIST<br />

9

FEATURE ARTICLE<br />

A Media Eclipse: Israel-Palestine and the World’s Forgotten Conflicts<br />

Israel is the largest recipient of US aid in the world, topping<br />

2.5 billion dollars in 2009. Although the majority of aid is<br />

tied to military spending, this works out to more than $400<br />

per Israeli. In 2006, Israel received 12% of all US foreign<br />

assistance while the whole of Africa (minus Egypt) received<br />

12%. For reference, the population of Israel is 7.3 million.<br />

<strong>The</strong> African continent is home to over 1 billion. GDP per<br />

capita in Israel is $28 900 while the average African GDP<br />

is under $3 000. With 300 million Africans living below the<br />

poverty line and 27% of their children malnourished, it is<br />

not difficult to argue that US aid is closely tied to its own<br />

interests and not to where it is needed most.<br />

<strong>The</strong> tragedy of disproportionate aid is that it perpetuates the<br />

conflict – perhaps intentionally – providing little incentive<br />

for leaders to move beyond the status quo. Military aid to<br />

Israel has fostered belligerence, political rigidity, and a<br />

regional arms race. Israeli governments act with impunity<br />

knowing that the US is loath to<br />

withdraw aid. <strong>The</strong> UNRWA has<br />

propped up governments dedicated<br />

to violence, seen millions of dollars<br />

siphoned off by officials, and has<br />

employed known terrorists. Former<br />

UNRWA general-counsel James G.<br />

Lindsay stated in 2009 that the<br />

UNRWA “has taken very few steps<br />

to detect and eliminate terrorists<br />

from the ranks of its staff or its<br />

beneficiaries, and no steps at all to<br />

prevent members of organizations<br />

such as Hamas from joining its<br />

staff. [...] No justification exists for<br />

millions of dollars in humanitarian<br />

aid going to those who can afford<br />

to pay for UNRWA services.”<br />

Accordingly, Canada redirected<br />

aid earmarked for the UNRWA<br />

to projects strengthening the Palestinian judicial system<br />

to “ensure accountability and foster democracy.” In short,<br />

not only does disproportionate aid leave millions of others<br />

worse off, it helps reinforce intransigence in the IPC thus<br />

propagating its survival.<br />

<strong>The</strong> greatest consequence of disproportionate media<br />

coverage is that many conflicts involving gross violations<br />

of human rights never reach the public consciousness. As<br />

demonstrated above, the rights of Liberians, Sudanese,<br />

Sri Lankans, North Koreans, Rwandese, Colombians,<br />

Congolese, Guineans, Burmese, Nigerians, Sierra Leoneans,<br />

Mexicans, Tibetans, Chechens, Sahrawis, Kurds, Kashmiris,<br />

albinos, women, homosexuals, children, and even those of<br />

Palestinians outside the Occupied Territories have been<br />

largely ignored. While the slightest event in the IPC (such<br />

image credit: flickr “bissane Gaza Solidarity ”<br />

as the building of an Israeli museum on top of a 15th century<br />

Palestinian cemetery parking lot) is covered in nearly every<br />

major Western newspaper, ongoing human rights abuses in<br />

the rest of the world (such as the continued killing of Sudanese<br />

civilians) do not. CNN International’s one year retrospective<br />

on the ‘War in Gaza’ is a fitting example: during the show,<br />

two statistics scrolled by at the bottom of the screen “...15 000<br />

civilians estimated dead in Mexico drug wars...225 000 child<br />

slaves in Haiti.” That these disturbing realities were not the<br />

focus of the show – rather than a war that had ended one year<br />

ago – is further evidence that the media’s fascination with the<br />

IPC outstrips that of any other conflict today, regardless of<br />

the scale of human rights abuses.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Solutions<br />

Redressing the media balance will not be simple: after<br />

decades of reinforcement the IPC is firmly entrenched in the<br />

hearts and minds of Westerners, Arabs, and Muslims alike.<br />

However, if one conflict can turn so many heads, so can<br />

others. <strong>The</strong> international media reaction to Darfur, while too<br />

late, likely stopped further atrocities and was an indication<br />

that diversification of human rights coverage is possible.<br />

Unfortunately, most conflicts don’t have enough geopolitical,<br />

ideological, or religious significance to trigger a global<br />

response. However, as outlined above, global media consumers<br />

are motivated to act on behalf of others when self-interest<br />

and/or guilt are present. While difficult to manufacture, these<br />

sentiments can be communicated through various conduits<br />

such as images and world leaders.<br />

A single image from the Ethiopian famine of 1984 sparked<br />

an unparalleled response from the international community.<br />

10<br />

THE LONDON GLOBALIST

Since then, horrific and shocking images of suffering are<br />

required if a natural disaster or conflict is to penetrate the<br />

public’s consciousness. Both the Palestinians and Israelis<br />

harness this potential expertly. Unfortunately, other conflicts<br />

are unable to generate images due to lack of access and<br />

material. <strong>The</strong>re were no images of the LRA massacre in DRC<br />

because there were no reporters. “You cannot fight for what<br />

you do not see,” was the<br />

reply of a Congolese<br />

villager when asked if<br />

he begrudged the world<br />

for ignoring his plight.<br />

Similarly, there were<br />

few images of the 20 000 dead Sri Lankan civilians due to<br />

government media restrictions. However, citizen journalism<br />

– whereby civilians are armed with smart technology that<br />

can easily diffuse images of suffering – has proven to be an<br />

effective awareness-raising technique that erases problems<br />

of both access and material.<br />

“<strong>The</strong> greatest consequence of disproportionate media<br />

coverage is that many conflicts involving gross violations<br />

of human rights never reach the public consciousness.”<br />

However, even if images are produced they are often<br />

ineffectual on the receiving end due to overload and<br />

sensitization. <strong>The</strong> competition between tragedies is fierce<br />

and can quickly overwhelm the media consumer to the<br />

point of inaction. One awareness-raising method that has<br />

proven to be remarkably effective is using world leaders to<br />

diffuse messages. Particularly powerful is the celebrity-asspokesperson<br />

approach. While it may seem trivial, the level<br />

of importance the world attributes to its celebrities cannot<br />

be underestimated. Concerts for debt relief, telethons for<br />

earthquake victims, and special UN goodwill ambassadors<br />

have all proven exemplary at helping causes rise from<br />

obscurity and into the living room of the mass media<br />

consumer.<br />

Once images are generated – and world leaders and celebrities<br />

attached to them – they can be used as tools by activists and<br />

diasporas to instigate change. Again, Palestinians and Israelis<br />

demonstrate that this method can be exceptionally effective<br />

for publicizing discontent. <strong>The</strong> cynic, of course, would argue<br />

that the media is a vehicle of the agenda-setting elite and that<br />

any attempt to breach the hegemony is futile. While pushing<br />

unheralded stories<br />

through various media<br />

channels is not easy,<br />

recent WTO and antiwar<br />

demonstrations<br />

have shown it is<br />

possible. In addition, recent campaigns by human rights<br />

groups such as Amnesty International and Human Rights<br />

Watch have confirmed civil society’s importance in public<br />

debate and demonstrated that if communal will is strong<br />

enough, change is possible.<br />

Conclusion<br />

<strong>The</strong> debate surrounding humanitarian intervention and<br />

the responsibility to protect has stalled. In the meantime,<br />

soft power in the form of the global media should be used to<br />

ensure equal representation. This will, in turn, ignite public<br />

opinion and promote change without infringing on state<br />

sovereignty. While perfectly equal representative coverage<br />

would be difficult to achieve, proportionate diversified<br />

coverage is entirely possible.<br />

This does not imply that support for Palestinians or Israelis<br />

should be abandoned; only that it should be shared with<br />

those who are ignored. If our moral code guides us in the<br />

IPC then let it be our beacon elsewhere as well. Concern for<br />

human right’s abuses needs to stretch beyond a small patch<br />

of land in the Middle East.<br />

FEATURE ARTICLE<br />

image credit: flickr “Julien Harneis”<br />

Noah Bernstein<br />

n.bernstein@lse.ac.uk<br />

A Media Eclipse: Israel-Palestine and the World’s Forgotten Conflicts<br />

11

Cry Havoc!<br />

And Let Slip the Drones of War...<br />

Since 2004, Washington has waged a relatively covert campaign against<br />

Islamist militant movements in Pakistan’s North-western regions. In the<br />

past two years, the campaign has increased considerably, drawing international<br />

criticism. As a part of the criticism, two questions have become<br />

commonplace: Is the campaign effective, and is it justifiable?<br />

Cry Havoc! And Let Slip the Drones of War...<br />

Background<br />

In America’s Global War on Terror (GWOT), there have<br />

been two major theatres, Afghanistan and Iraq. Both<br />

countries experienced forceful removal of old regimes<br />

by an American-led invasion followed by attempted statebuilding<br />

campaigns; the ideological premises of these actions<br />

could not to survive realities on the ground. Perhaps<br />

inevitably, both countries saw a rise in insurgent activity,<br />

leaving the occupying forces to wage counter-terrorism and<br />

counter-insurgency campaigns. While the Islamist uprising<br />

in Iraq seems to be waning, the neo-Taliban insurgency in<br />

Afghanistan is gathering pace.<br />

A substantial element in the persistence of the neo-Taliban<br />

threat results from the region’s geopolitical peculiarities. <strong>The</strong><br />

terrain in Afghanistan, especially near the Pakistani border,<br />

offers a natural safe-haven for insurgents. <strong>The</strong> mountain<br />

ranges in South-eastern Afghanistan and North-western<br />

Pakistan have been a permanent base since 1979. It has not<br />

helped that insurgents inside Afghanistan have established<br />

a regional infrastructure network to facilitate the smuggling<br />

of arms, drugs and munitions, taking full advantage of the<br />

porous borders surrounding them, which also enabled crossborder<br />

raids.<br />

<strong>The</strong> quintessential beneficiary, and more recently, victim<br />

of Afghanistan’s porous borders has been Pakistan. After<br />

the withdrawal of Soviet forces, Pakistan sought to install a<br />

friendly regime in Kabul, most recently in the form of Taliban,<br />

to gain strategic depth in its rivalry against India. However,<br />

the pyrrhic nature of Pakistan’s Taliban-policy became<br />

clear as the neo-Taliban insurgency intensified. Pakistan’s<br />

efforts to support the Taliban backfired and led to the talibanization<br />

of Pakistan’s own Pashtun-dominated areas in the<br />

North-western Frontier Provinces (NWFP) and Federally<br />

Administrated Tribal Areas (FATA). <strong>The</strong>se areas suffered<br />

from Pashtun irredentism generated by the often ambiguous<br />

Durand Line, reinforced by genuine social grievances, lack of<br />

government legitimacy and absence of public services.<br />

<strong>The</strong> intensification of the Islamist insurgency in Pakistan<br />

meant NWFP and FATA became a sanctuary and an operational<br />

base for militants, conveniently out of ground forces<br />

reach. International forces were unable to engage the militants<br />

on the Pakistani side of the border and other than<br />

establishing a presence in South Waziristan, the Pakistani<br />

military has largely resisted launching large-scale assaults<br />

on the militant strongholds. Despite mounting pressure on<br />

Pakistan’s military to deal with militant-controlled areas,<br />

the insurgents have established a virtual safe-haven in the<br />

regional provinces. <strong>The</strong> question on the Pentagon’s mind is<br />

how to resolve this problem.<br />

Drone <strong>The</strong>m into the Stone Age<br />

Washington’s air campaign in the NWFP and FATA tribal regions<br />

has become the cornerstone of counter-insurgency and<br />

counter-terrorism strategy in Pakistan. Operations started<br />

after Washington became increasingly frustrated over perceived<br />

failure by Islamabad to prevent the militant action<br />

and infiltration into Afghanistan. Since 2004, Washington<br />

has conducted a covert program to target and eliminate<br />

al-Qaeda and Taliban commanders and fighters, including<br />

their external operations networks based in Pakistan’s tribal<br />

regions. According to New America Foundation (NAF) and<br />

the Long War Journal (LWJ), who have been compiling a database<br />

on the drone campaign, there have been 10 Predator<br />

drone strikes between 2004 and 2007. Casualty estimates<br />

vary between 87 and 109- of which 77 to 100 were militantskeeping<br />

civilian deaths to a minimum.<br />

12<br />

THE LONDON GLOBALIST

<strong>The</strong> Obama Administration has not viewed such numbers as<br />

credible deterrents against militants operating in and out of<br />

NWFP and FATA- prioritizing the strategic importance of<br />

disrupting militant activity in the tribal regions. <strong>The</strong> drone<br />

campaign has now become the foundation of Washington’s<br />

counter-terrorism in Pakistan. <strong>The</strong> objective has not<br />

changed: to root out and decapitate senior leadership of al<br />

Qaeda, the Taliban, and other allied terror groups, like the<br />

Haqqani Network (HQN) and Tehrik-i-Taliban (TTP) to<br />

disrupt al-Qaeda’s global and local operations in the region.<br />

However, the intensity has increased, including considerations<br />

in March 2009 to widen its geographic scope to include<br />

Balochistan.<br />

Osama al-Kini, al-Qaeda’s operations chief in Pakistan and<br />

one of the masterminds behind the embassy bombings in<br />

Kenya and Tanzania. Moreover, drone strikes have claimed<br />

numerous HQN leaders. NAF and LWJ both report that<br />

while the attacks have increased, civilian casualties have remained<br />

relatively low.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Strategic Impact of the Drone Attacks<br />

<strong>The</strong> drone attacks are a typical tool in Washington’s arsenal<br />

to combat militant activity in Pakistan. However, prevalence<br />

of the drone strategy does not necessarily imply effectiveness.<br />

While there is considerable support for the continuation, if<br />

“If we want to strengthen<br />

our friends and weaken our<br />

enemies in Pakistan, bombing<br />

Pakistani villages with<br />

unmanned drones is totally<br />

counterproductive”<br />

image credit: flickr “Helmandblog ”<br />

“Washington’s air campaign in Pakistan’s tribal region<br />

has become the cornerstone of counter-insurgency and<br />

counter-terrorism strategies in Pakistan.”<br />

Correlating with the intensifying insurgency, Predator drone<br />

strikes increased to 34 in 2008 and 59 in 2009. 2010 has<br />

already witnessed 25 strikes. <strong>The</strong> casualty levels have also<br />

grown increasingly. According to NAF, “the 122 reported<br />

drone strikes in northwest Pakistan, including 26 in 2010,<br />

from 2004 to the<br />

present have killed approximately<br />

between<br />

867 and 1,281 individuals,<br />

of whom around<br />

582 to 915 were described<br />

as militants in reliable press accounts, about twothirds<br />

of the total on average.” <strong>The</strong> increasing number of<br />

drone attacks has resulted in the elimination of several notable<br />

militants. Between 2004 and 2007, only four top-level<br />

militants were neutralised.<br />

In contrast, by 2009, the drone strikes have caused the death<br />

of Baitullah Mehsud, leader of TTP, his deputy, in addition<br />

to Saleh al-Somali, al-Qaeda’s external network leader, and<br />

THE LONDON GLOBALIST<br />

not escalation of the drone attacks, there are also critical voices<br />

being heard. Dr. David Kilcullen, one of the leading thinkers<br />

on counterinsurgency, and an advisor to both General<br />

David Petraeus and former Secretary of State Condoleezza<br />

Rice, errs on the side of caution: “If we want to strengthen<br />

our friends and<br />

weaken our enemies<br />

in Pakistan, bombing<br />

Pakistani villages with<br />

unmanned drones is<br />

totally counterproductive”<br />

he quipped in an interview with Danger Room, a notable<br />

national security blog, in early 2009.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is logic to Dr. Kilcullen’s argument. On the one hand,<br />

while eliminating terrorists will no doubt reflect well on<br />

Obama’s domestic approval ratings, it does little to address<br />

the strategic balance between the insurgents and the counter-insurgency<br />

efforts. It can hardly prevent cross-border<br />

infiltration into Afghanistan and in the medium term will<br />

Cry Havoc! And Let Slip the Drones of War...<br />

13

likely drive an increasing number of militant leaders underground,<br />

making it more difficult to gather intelligence.<br />

Furthermore, Pakistani authorities have systematically condemned<br />

American drone attacks on their territory, despite an<br />

alleged “mutual understanding” behind the scenes. While there<br />

undoubtedly is coordination between Islamabad and Washington<br />

on the drone campaign, it is most likely to further decrease<br />

Drones are best utilized as a surgical strike force, to be used<br />

sparingly against high-value targets. <strong>The</strong>y cannot change<br />

the strategic balance in Pakistan against the militants, and<br />

neither should they be deployed as cost-effective, risk-averse<br />

extrajudicial assassination schemes. This only furthers the<br />

alienation of the Pakistani population. Many Islamabad officials<br />

have long claimed drone attacks fuel the insurgency,<br />

only to have their statements fall on deaf ears in Washington.<br />

“Sometimes we might have to<br />

[attack with drones] — but<br />

only where larger interests<br />

(say, stopping another 9/11)<br />

are directly affected…”<br />

Dr David Kilcullen<br />

Cry Havoc! And Let Slip the Drones of War...<br />

the legitimacy of Pakistan’s capital in the tribal regions. Likewise,<br />

the drone strikes have further upset the delicate balance<br />

in FATA and NWFP - tipping it in favour of the militants,<br />

who are ready and eager to exploit the upheaval caused<br />

by attacks. While “low civilian casualties” might be acceptable<br />

to the Pentagon, it is unlikely that such acceptance exists<br />

in Peshawar, or even Islamabad. Civilian casualties are<br />

consistently exaggerated in the Pakistani press, further aggravating<br />

domestic opinion of Washington. In a Gallup poll<br />

conducted in August 2009, paltry nine percent of Pakistanis<br />

expressed support for the drone strikes, while 67% opposed<br />

them. Comparatively, 41% supported military action against<br />

the Islamist militants by the Pakistanis, while only 24% opposed<br />

such actions.<br />

However, the drones can have a role in this conflict. As<br />

Kilcullen also noted in the interview with Danger Room,<br />

“Sometimes we might have to [attack with drones] — but<br />

only where larger interests (say, stopping another 9/11) are<br />

directly affected… ...We need to be extremely careful about<br />

undermining the longer-term objective - a stable Pakistan.”<br />

This reveals the overall problem of Obama’s drone strategy.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is considerable overreliance on drone attacks, and little<br />

consideration over their impact on the socio-political dynamics<br />

in the tribal areas and wider Pakistan.<br />

However, no effective counterinsurgency strategy can ignore<br />

the population. This might become a lesson Washington<br />

needs to learn again.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Next Generation War Criminals<br />

Herein lies an additional problem facing the Obama Administration’s<br />

drone campaign. Forget strategic limitations of the<br />

drone attacks and their operational misuse, it is within the<br />

political, or legal battleground that the additional negative<br />

implications of the drone campaign are found.<br />

Problematically, it is not the US military that is in charge of<br />

the drone campaign in Pakistan. Although the drones over<br />

the Afghani skies fly under Air Force command, their jurisdiction<br />

ends at the border. On the other side, the Central Intelligence<br />

Agency (CIA) takes over. Hence, this puts Washington<br />

in an awkward position for two reasons. First, as the<br />

drone attacks are CIA operations, Washington is in a position<br />

where it can neither confirm nor deny the occurrence of these<br />

attacks. Essentially, this means that Washington is waging a<br />

publicly known “secret war” in Pakistan. Washington’s inability<br />

to address the aftermath of these attacks, either vis-àvis<br />

Pakistan or the international community will surely create<br />

further schism as the campaign intensifies. Second, CIA’s<br />

operational responsibility casts doubt over the legal status of<br />

14<br />

THE LONDON GLOBALIST

the pilots as civilian participation in combat is prohibited by<br />

two protocols of the 1949 Geneva Convention. According to<br />

several critics of the drone campaign, this ironically brands<br />

the drone pilots as unlawful combatants under international<br />

law. In theory, this opens the door to prosecute the pilots and<br />

top US officials as war criminals in the future.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ambiguous legal position of pilots has left Washington<br />

scrambling for a justification of the attacks. In a recent conference<br />

address, State Department Legal Adviser Harold<br />

Koh stated that: “<strong>The</strong> United States is in “an armed conflict”<br />

with Al-Qaeda, the Taliban<br />

and its affiliates as a result of<br />

the September 11 attacks, and<br />

may use force consistent with<br />

its inherent right to self-defence under the international<br />

law.” Washington’s drone policy neatly underlines the political<br />

subjectivities of applying international law to the GWOT<br />

and the drone campaign. Prior to September 11 attacks,<br />

former CIA chief George Tenet argued that for the CIA to<br />

deploy drones like the Predator, would be a “terrible mistake.”<br />

But the current CIA chief, Leon Panetta acknowledges<br />

the strategic utility of Predator drones in the battle against<br />

Islamist militants. For Panetta, strategic benefits, not legality,<br />

matter the most.<br />

“Washington needs to realize the drone attacks<br />

do not occur in a strategic vacuum.”<br />

disregard by the Obama Administration for the effects of<br />

the drone attacks presents a major strategic pitfall. In order<br />

to optimize its current strategy fully reap the benefits<br />

from using drones, Washington needs to redress several<br />

problems. First, it needs to reconsider the role of the CIA.<br />

<strong>The</strong> problematic status of the unlawful pilots, the erosion of<br />

extrajudicial assassinations and U.S. inability to address the<br />

drone campaign publicly will likely alienate Washington’s<br />

European allies and Pakistan, who can do little more than<br />

publicly condemn the attacks. Second, the over reliance and<br />

excessive deployment of the drones to strike various targets<br />

will further alienate Islamabad,<br />

and turn popular opinion<br />

against Washington’s counterinsurgency<br />

efforts. While<br />

Washington is unlikely to make any new friends in Pakistan,<br />

it needs to better balance the gains of neutralizing militants<br />

and disrupting their operations with the negative repercussions<br />

of continuous drone attacks in a hostile environment.<br />

Additionally, whether one ultimately agrees with the legitimacy<br />

and justifiability of the attacks, extrajudicial assassinations<br />

of terrorists is likely to contribute to an already visible<br />

trend, making ‘targeted killings’ more acceptable. After all,<br />

it was not long ago Washington coherently condemned Tel<br />

Aviv’s inclination to use ‘targeted killings’ of Palestinian militants.<br />

Likewise, the assassination of Hamas military commander<br />

Mabhoud al-Mabhoub in Dubai drew robust international<br />

criticism, and was also condemned by Washington.<br />

<strong>The</strong> erosion of the moral and legal status of extrajudicial<br />

targeting is likely to make the assassination of individuals<br />

more commonplace. A question that cannot be substantially<br />

answered now arises: how will Islamist militants respond to<br />

such occurrences?<br />

<strong>The</strong> Drone Question: Problems and Prospects<br />

Washington’s drone campaign faces many problems, but is<br />

not an entirely useless policy in the fight against insurgents<br />

and terrorists in Pakistan. <strong>The</strong> initial criticism toward Pakistan’s<br />

inability or unwillingness to earnestly exert pressure<br />

over the militants operating in the tribal region rings true,<br />

and Pakistan’s course is unlikely to change radically in the<br />

near future. With the absence of any other threats to the<br />

militants in NWFP and FATA, the drone campaign presents<br />

one of the few viable policy options. <strong>The</strong> drones are capable<br />

of performing surgical strikes to eliminate high-value<br />

targets within the senior leadership of Islamist movements,<br />

disrupting their regional operations. However, the drone attacks<br />

also have a destabilizing effect.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y generate more grievances against the GWOT and Islamabad,<br />

further fuelling the insurgency. <strong>The</strong> perceived<br />

image credit: flickr “Swamibu ”<br />

Washington needs to realize the drone attacks do not occur<br />

in a strategic vacuum. <strong>The</strong>re is no long-term solution<br />

without a stable Pakistan. And while the drone attacks offer<br />

a limited resource against the militant problem, they also<br />

present a long-term contradiction by fuelling the insurgency<br />

and increasing the legitimacy deficit of Islamabad. Washington<br />

needs to find a balance between these elements. If the<br />

U.S. government wishes to further intensify its drone campaign,<br />

as advocated by former RAND analyst Seth Jones, it<br />

needs to find a way to alleviate its impact in Pakistan. Thus<br />

far, such approach has been lacking in Obama’s “Secret War<br />

in Pakistan”.<br />

Juha Saarinen<br />

j.p.saarinen@lse.ac.uk<br />

www.postgradbonanza.wordpress.com<br />

Cry Havoc! And Let Slip the Drones of War...<br />

THE LONDON GLOBALIST<br />

15

<strong>The</strong> Great Game<br />

Redux<br />

As Western forces gear for a withdrawal from the Afghan theatre, regional<br />

powers prepare to face-off in a shadowy proxy war for the control of the<br />

crossroads of Asia.<br />

Coined by 19th century British imperialists, the term<br />

Great Game was used to illustrate the Russian-British<br />

geo-political struggle for dominance on the strategic<br />

chessboard of Afghanistan and Central Asia. Marked by limited<br />

military engagements and intelligence forays, the Great<br />

Game was the Machiavellian embodiment of great-power<br />

politics and dominance in the region.<br />

Western as well as Indian intelligence sources, stem from its<br />

strenuous efforts to contain India and re-gain its lost strategic<br />

depth once Western forces evacuate the country. In a rare media<br />

briefing to journalists in February, General Ashfaq Pervez Kayani,<br />

Pakistan’s powerful Chief of Army Staff, put it succinctly,<br />

Fast-forward to a century later and the game still continues.<br />

This time, however, the number of players has proliferated,<br />

the intensity of the violence is deadlier and the regional<br />

stakes are much higher. Seven years after being toppled by<br />

an American invasion, the Taliban has staged a bloody comeback<br />

as the besieged Hamid Karzai administration is rapidly<br />

losing credibility both home and abroad. Afghanistan is once<br />

again a proxy battleground as regional powers such as India,<br />

Pakistan, Russia, China and Iran jockey for power and influence<br />

in a nation poised on a razor’s edge.<br />

India and Pakistan<br />

<strong>The</strong> Great Game Redux<br />

Augmenting its soft power, India is playing a major developmental<br />

role by pledging more than $1.2 billion to build<br />

Afghanistan’s shattered infrastructure. Some of the major<br />

Indian development projects include the new parliament<br />

building, erecting power transmission lines in the north, and<br />

building roads to facilitate transport. This rising Indian profile<br />

in Afghanistan has rattled Pakistan as the two archrivals<br />

escalate their presence in the war-torn country. Pakistani officials<br />

accuse Indian embassies and consulates in Afghanistan<br />

of arming, training and funding Baloch insurgents as<br />

well as elements of the Pakistani Taliban for sabotage and<br />

subversion operations against Pakistan. In the same vein,<br />

India blames Pakistan for rising attacks against Indian interests<br />

within Afghanistan. <strong>The</strong> Indian Embassy in Kabul has<br />

been the site of two deadly suicide bombings blamed on local<br />

Taliban elements. Allegedly aided by Pakistan’s Inter-Services<br />

Intelligence (ISI), an increasing number of Indian nationals<br />

working on reconstruction projects have been targeted.<br />

Islamabad’s continuing links with the Taliban, reinforced by<br />

image credit: flickr “DVIDSHUB ”<br />

“Afghanistan is once again a proxy<br />

battleground as regional powers<br />

such as India, Pakistan, Russia,<br />

China and Iran jockey for power<br />

and influence in a nation poised on<br />

a razor’s edge.”<br />

16

“We want a strategic depth in Afghanistan but do not want<br />

to control it”, he adds, “A peaceful and friendly Afghanistan<br />

can provide Pakistan strategic depth.” Pakistan’s readiness to<br />

train the Afghan army in response to a similar offer made by<br />

New Delhi reflects Islamabad’s concerns over rising Indian<br />

influence in Kabul. Expect a rising body count as an intensifying<br />

proxy war between the two mortal foes plays out in the<br />

Afghan theatre.<br />

“...the Chinese have seemingly announced<br />

their intentions of leveling<br />

the playing field with the US through<br />

economic and possibly military assistance<br />

to Afghanistan.”<br />

Russia<br />

Still smarting from its disastrous intervention in Afghanistan<br />

in the 1980’s, Russia has no stomach for another military adventure<br />

in the region. Yet, the Kremlin harbors no desire to<br />

witness another Taliban takeover in its strategic backyard<br />

which could embolden Jihadist fighters in Chechnya, Dagestan<br />

and Central Asia as a whole. Having faced the ignominy<br />

of a military defeat in Afghanistan, the Russians are<br />

more interested in a diplomatic rather than military solution<br />

to the crisis and provide significant economic assistance to<br />

the Hamid Karzai government in Kabul. Moscow views with<br />

image credit: flickr “rob7812 ”<br />

image credit: flickr “Chronic420life ”<br />

disquiet the increasing American military presence in the<br />

region, as well as recent American overtures to Central<br />

Asian countries for bilateral transit treaties that would allow<br />

the flow of critical military supplies into Afghanistan as<br />

an alternative to Pakistan. Not willing to play second fiddle<br />

to their Cold War rivals and highly suspicious of Pakistani<br />

machinations, the Russians have stepped up their engagement<br />

with the Karzai administration in tandem with key<br />

players such as Iran and India through regional forums<br />

such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).<br />

China<br />

Another major actor in the arena, China has huge stakes<br />

in a stable and prosperous Afghanistan to secure its Western<br />

corridor in order tap its growing energy interests in<br />

Pakistan, Iran and Central Asia. Moreover, Beijing is wary<br />

of a Taliban victory as this could directly impact the restive<br />

Muslim-majority province of Xinjiang. Like its enormous<br />

African safari, Beijing is also pumping<br />

massive economic firepower into infrastructure<br />

projects in Afghanistan. With<br />

an eye on Africa’s treasure trove of natural<br />

resources, China has embarked on a massive<br />

aid and investment spree to modernize<br />

the continent’s creaking infrastructure<br />

by building new and better roads, schools,<br />

computer networks, telecoms systems and<br />

power plants. While China’s foray into Afghanistan<br />

barely measures that of Africa,<br />

Beijing has reportedly promised to invest<br />

$3 billion in one of the world’s largest copper<br />

mines south of Kabul. Through this<br />

calculated maneuver, the Chinese have<br />

seemingly announced their intentions<br />

of leveling the playing field with the US<br />

through economic and possibly military<br />

assistance to Af- ghanistan. On the eve of President Karzai’s<br />

bilateral visit to Beijing in March, Zhang Xiaodong, Deputy<br />

Chief of the Chinese Association for Middle East Studies,<br />

told the government-owned China Daily, “As Afghanistan’s<br />

neighbour, China is very concerned about the country’s<br />

future”. In a subtle hint of shifting geopolitical priorities,<br />

Zhang hinted, “Afghanistan should cut reliance on the US.<br />

At the moment, Washington is deeply involved, and it makes<br />

other neighbours nervous. Karzai now hopes to seek more<br />

support from other big countries and find a diplomatic balance,”<br />

At the twilight of the Afghan War, the stage is set for<br />

Beijing’s increasing involvement in its embattled neighbourhood.<br />

Iran<br />

Finally, Afghanistan’s enormous neighbour to the west, Iran,<br />

faces a dangerous ideological adversary in the Sunni Taliban.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Iranians will not easily forego the brutal murder of their<br />

<strong>The</strong> Great Game Redux<br />

THE LONDON GLOBALIST<br />

17

diplomats at the hands of the Taliban in 1998 that almost escalated<br />

into a military conflict. <strong>The</strong> regional giant commands<br />

significant influence among the Shia Hazara minority as it<br />

also pumps in significant economic investment to develop<br />

the country. Tehran certified joint investment companies,<br />

sponsored food fairs, opened cement factories, extended<br />

purchase credits to traders, and trained commercial pilots.<br />

<strong>The</strong> extension of an electric<br />

line into the western Afghan<br />

city of Herat and joint sponsorship<br />

of highway projects<br />

with India throughout the<br />

Afghan west have been some<br />

of Tehran’s key projects. While Iran is loath to accept a Taliban<br />

take-over of Afghanistan, it is wary of the presence of<br />

US-led NATO troops on its eastern frontier. Pentagon officials<br />

allege that Tehran supplies arms and other material<br />

to Taliban insurgents and other groups in Western Afghanistan.<br />

With Iran’s deepening ties with various Afghan communities<br />

such as the Shia Hazara and others, it is inevitable<br />

that any heightening of US-Iranian tensions can be played<br />

out in a violent proxy face-off in the fiery deserts of the wartorn<br />

nation.<br />

“While Iran is loath to accept a Taliban take-over<br />

of Afghanistan, it is wary of the presence of US-led<br />

NATO troops on its eastern frontier.”<br />

In the aftermath of the <strong>London</strong> Conference, the end game<br />

has intensified fears of further instability as Western forces<br />

gear for an eventual withdrawal. Held on January 28th<br />

2010, the <strong>London</strong> Conference, attended by major actors in<br />

the international community, endorsed plans to transfer<br />

military leadership from NATO to Afghan security forces<br />

beginning at the end of this year and for the reintegration of<br />

the Taliban into the Afghan<br />

political structure via monetary<br />

benefits. Simmering<br />

tensions between regional<br />

powers are likely to boil<br />

over as consensus emerges<br />

regarding negotiations with the Taliban. A possible political<br />

settlement with the Taliban, with the involvement of Pakistan,<br />

is likely to spark reactions from India, China, Iran and<br />

Russia including the backing of other anti-Taliban groups<br />

undermining any peace and stability in the region. Recent<br />

weeks have witnessed an upsurge in regional diplomacy as<br />

world leaders shuttled between New Delhi, Moscow, Kabul,<br />

Islamabad and Tehran - be it Prime Minister Manmohan<br />

Singh’s visit to Riyadh, President Mahmoud Ahmedinajad<br />

’s visit to Kabul, President Hamid Karzai’s visit to Islamabad,<br />

or Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s visit to Delhi. As<br />

the clock in Afghanistan ticks down, the coming weeks and<br />

months are likely to witness an escalation of intensity in the<br />

cloak and dagger game being played between regional powers<br />

for the ultimate prize that is Afghanistan.<br />

image credit: flickr “Chuck Holton”<br />

Brijesh Khemlani<br />

b.khemlani@lse.ac.uk<br />

“...the coming weeks and months<br />

are likely to witness an escalation<br />

of intensity in the cloak and dagger<br />

game being played between regional<br />

powers for the ultimate prize that<br />

is Afghanistan.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> Great Game Redux<br />

18

YOU can light up a life today!<br />

Clean, healthy solar light replaces toxic<br />

and harmful kerosene.<br />

Visit www.onemillionlights.org to learn more and get involved<br />

• donate a solar light!<br />

• Host a fundraiser<br />

• Become an ambassador<br />

• Volunteer!

Intervi<br />

“To say we are giving upon markets is actually<br />

almost to say we are giving up.”<br />

Interview with Lord Nicholas Stern<br />

image credit: flickr “World Economic Forum”<br />

TStern is a refreshing<br />

experience;<br />

pragmatic approach leaves<br />

space for constructive solutions<br />

alongside criticism.<br />

He famously published<br />

the Stern Review in 2006,<br />

presenting climate change<br />

as the result of market<br />

alking to Nicholas<br />

failure and subsequently<br />

provides market-based<br />

solutions. Among other<br />

things, he currently chairs<br />

the Grantham Institute for<br />

Climate Change and the<br />

Environment at the LSE<br />

and heads the India Observatory<br />

within the Asia<br />

Research Centre.<br />

Despite the shortcomings<br />

of the Copenhagen<br />

Summit, Stern retains a<br />

positive outlook, insisting<br />

we should view it as a<br />

platform for future<br />

change. It is easy to be<br />

sceptical of this optimism,<br />

perhaps partly because the<br />

summit was presented to the<br />

average person as the summit,<br />

where countries would<br />

agree on binding emissions<br />

plans and stringent<br />

targets. When these did<br />

not materialise, it seemed<br />

a significant opportunity<br />

had been wasted. Stern<br />

admits the disappointment,<br />

but at the same time notes<br />

it could have been much<br />

worse and, in support of<br />

his hopefulness, points to<br />

several positive, concrete<br />

results. One outcome was<br />

recognition of the need to<br />

limit global warming to 2<br />

degrees, the implications<br />

of which amount to some<br />

radical action. He outlined<br />

the following figures: we<br />

currently emit around<br />

47 billion tonnes of CO2<br />

equivalent per annum; to<br />

meet the target we would<br />

have to reduce this to<br />

around 44 billion tonnes<br />

in 2020, well below 35<br />

in 2030 and 20 in 2050.<br />

Presumably then, the challenge<br />

faced by countries at<br />

the future climate summit<br />

in Cancun, Mexico, will be<br />

to lay down more concrete<br />

plans for achieving this; no<br />

small feat considering the<br />

inevitable political wrangling.<br />

However even here<br />

there are indicators that it<br />

is possible to work together.<br />

<strong>The</strong> High-level Advisory<br />

Group on Climate Change<br />

Financing, responsible for<br />

investigating how to spend<br />

the money promised at Copenhagen,<br />

will be chaired<br />

by both Gordon Brown<br />

and Mr. Meles Zenawi,<br />

Prime Minister of the Federal<br />

Democratic Republic<br />

of Ethiopia.<br />

On a more local level, we<br />

face the challenge of making<br />

our government commit<br />

to meaningful domestic<br />

initiatives to combat<br />

climate change. Undeniably<br />

the government has a<br />

large role to play, especially<br />

in Stern’s rhetoric where<br />

emissions are an externality<br />

that must be addressed<br />

through government intervention.<br />

However, the<br />

question remains over how<br />

best to mobilise our politicians.<br />

Should we portray<br />

the long-term benefits (be<br />

it humanitarian or economic)<br />

or should we appeal<br />

to their short-term<br />

electoral interests? Stern<br />

opts for the former: he<br />

feeds research papers and<br />

policy into government to<br />

convince them of the necessity<br />

and benefits of action.<br />

<strong>The</strong> latter requires<br />

many individuals modify<br />

their behaviour to be more<br />

environmentally aware.<br />

This would prove people’s<br />

20<br />

THE LONDON GLOBALIST

ewith<br />

With the dust of Copenhagen still in the air, Hero Austin<br />

and Kimia Pezeshki converse candidly with worldrenowned<br />

climate economist Professor Nicholas Stern<br />

about the future of the climate change debate and his<br />

reasons for hope.<br />

Lord Nicholas Stern<br />

commitment to the issue,<br />

allowing parties to<br />

implement radical initiatives<br />

without fear of the<br />

electorate. In actuality, it<br />

transpires that both are<br />

crucial, even complementary.<br />

Stern’s policies and<br />

research provide sound,<br />

detailed evidence for the<br />

British government to act<br />

upon, but to ensure action,<br />

this has to be seconded by<br />

popular demand to reassure<br />

any party facing the<br />

electorate.<br />

Nevertheless Stern is clear<br />

that some approaches<br />

are simply not useful. We<br />

asked him about his views<br />