Feb-2015-s.41-handout-PMQC

Feb-2015-s.41-handout-PMQC

Feb-2015-s.41-handout-PMQC

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Western Circuit RASSO Course 28 <strong>Feb</strong>ruary <strong>2015</strong><br />

Section 41 YJCE Act 1999 – Philip Mott QC<br />

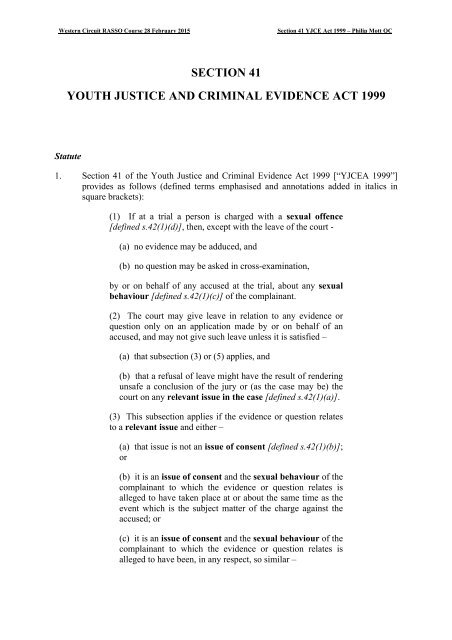

SECTION 41<br />

YOUTH JUSTICE AND CRIMINAL EVIDENCE ACT 1999<br />

Statute<br />

1. Section 41 of the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999 [“YJCEA 1999”]<br />

provides as follows (defined terms emphasised and annotations added in italics in<br />

square brackets):<br />

(1) If at a trial a person is charged with a sexual offence<br />

[defined s.42(1)(d)], then, except with the leave of the court -<br />

(a) no evidence may be adduced, and<br />

(b) no question may be asked in cross-examination,<br />

by or on behalf of any accused at the trial, about any sexual<br />

behaviour [defined s.42(1)(c)] of the complainant.<br />

(2) The court may give leave in relation to any evidence or<br />

question only on an application made by or on behalf of an<br />

accused, and may not give such leave unless it is satisfied –<br />

(a) that subsection (3) or (5) applies, and<br />

(b) that a refusal of leave might have the result of rendering<br />

unsafe a conclusion of the jury or (as the case may be) the<br />

court on any relevant issue in the case [defined s.42(1)(a)].<br />

(3) This subsection applies if the evidence or question relates<br />

to a relevant issue and either –<br />

(a) that issue is not an issue of consent [defined s.42(1)(b)];<br />

or<br />

(b) it is an issue of consent and the sexual behaviour of the<br />

complainant to which the evidence or question relates is<br />

alleged to have taken place at or about the same time as the<br />

event which is the subject matter of the charge against the<br />

accused; or<br />

(c) it is an issue of consent and the sexual behaviour of the<br />

complainant to which the evidence or question relates is<br />

alleged to have been, in any respect, so similar –

Western Circuit RASSO Course 28 <strong>Feb</strong>ruary <strong>2015</strong><br />

Section 41 YJCE Act 1999 – Philip Mott QC<br />

(i) to any sexual behaviour of the complainant which<br />

(according to evidence adduced or to be adduced by or<br />

on behalf of the accused) took place as part of the<br />

event which is the subject matter of the charge against<br />

the accused, or<br />

(ii) to any other sexual behaviour of the complainant<br />

which (according to such evidence) took place at or<br />

about the same time as that event,<br />

that the similarity cannot reasonably be explained as a<br />

coincidence.<br />

(4) For the purposes of subsection (3) no evidence or question<br />

shall be regarded as relating to a relevant issue in the case if it<br />

appears to the court to be reasonable to assume that the purpose<br />

(or main purpose) for which it would be adduced or asked is to<br />

establish or elicit material for impugning the credibility of the<br />

complainant as a witness.<br />

(5) This subsection applies if the evidence or question –<br />

(a) relates to any evidence adduced by the prosecution about<br />

any sexual behaviour of the complainant; and<br />

(b) in the opinion of the court, would go no further than is<br />

necessary to enable the evidence adduced by the prosecution<br />

to be rebutted or explained by or on behalf of the accused.<br />

(6) For the purposes of subsections (3) and (5) the evidence or<br />

question must relate to a specific instance (or specific<br />

instances) of alleged sexual behaviour on the part of the<br />

complainant (and accordingly nothing in those subsections is<br />

capable of applying in relation to the evidence or question to<br />

the extent that it does not so relate).<br />

(7) Where this section applies in relation to a trial by virtue of<br />

the fact that one or more of a number of persons charged in the<br />

proceedings is or are charged with a sexual offence –<br />

(a) it shall cease to apply in relation to the trial if the<br />

prosecutor decides not to proceed with the case against that<br />

person or those persons in respect of that charge; but<br />

(b) it shall not cease to do so in the event of that person or<br />

those persons pleading guilty to, or being convicted of, that<br />

charge.<br />

(8) Nothing in this section authorises any evidence to be<br />

adduced or any question to be asked which cannot be adduced<br />

or asked apart from this section.

Western Circuit RASSO Course 28 <strong>Feb</strong>ruary <strong>2015</strong><br />

Section 41 YJCE Act 1999 – Philip Mott QC<br />

2. Section 42 provides a number of definitions, as follows:<br />

(1) In section 41 –<br />

(a) “relevant issue in the case” means any issue falling to be proved by<br />

the prosecution or defence in the trial of the accused;<br />

(b) “issue of consent” means any issue whether the<br />

complainant in fact consented to the conduct constituting the<br />

offence with which the accused is charged (and accordingly<br />

does not include any issue as to the belief of the accused that<br />

the complainant so consented);<br />

(c) “sexual behaviour” means any sexual behaviour or<br />

other sexual experience, whether or not involving any<br />

accused or other person, but excluding (except in section<br />

41(3)(c)(i) and (5)(a)) anything alleged to have taken place<br />

as part of the event which is the subject matter of the charge<br />

against the accused; and<br />

(d) subject to any order made under subsection (2), “sexual<br />

offence” shall be construed in accordance with section 62.<br />

Checklist<br />

3. Ten steps should be followed in assessing whether leave should be given under <strong>s.41</strong> –<br />

(1) Is D charged with a sexual offence? [<strong>s.41</strong>(1)]<br />

(2) Is the proposed evidence or question “about any sexual behaviour of the<br />

complainant”? [<strong>s.41</strong>(1)]<br />

(3) Does it relate to a relevant issue and that issue is not an issue of consent?<br />

[<strong>s.41</strong>(3)(a)]; OR<br />

(4) Does it relate to a relevant issue and that issue is an issue of consent and the<br />

sexual behaviour is alleged to have taken place at or about the same time as the<br />

event charged? [<strong>s.41</strong>(3)(b)]; OR<br />

(5) Does it relate to a relevant issue and that issue is an issue of consent and the<br />

sexual behaviour alleged is so similar to other sexual behaviour of the<br />

complainant as part of the event charged or at or about the same time as that<br />

event? [<strong>s.41</strong>(3)(c)]<br />

(6) Only if step (4), (5) or (6) applies: Is the main purpose not merely to impugn the<br />

credibility of the complainant as a witness? [<strong>s.41</strong>(4)]<br />

(7) Does it relate to evidence adduced by the prosecution about the sexual behaviour<br />

of the complainant AND would go no further than is necessary to rebut or explain<br />

that evidence? [<strong>s.41</strong>(5)]

Western Circuit RASSO Course 28 <strong>Feb</strong>ruary <strong>2015</strong><br />

Section 41 YJCE Act 1999 – Philip Mott QC<br />

(8) Does the evidence or question relate to a specific instance or instances? [<strong>s.41</strong>(6)]<br />

(9) Might a refusal of leave have the result of rendering unsafe a conclusion of the<br />

jury on any relevant issue in the case? [<strong>s.41</strong>(2)(b)]<br />

(10) Has the correct procedure been followed?<br />

Sexual Offence (Step 1)<br />

4. The original s.62 pre-dated the Sexual Offences Act 2003 [“SOA 2003”] and covered<br />

offences such as rape or indecent assault. It has been amended by Schedule 26 to the<br />

Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008 to cover any offence under the SOA 2003,<br />

part 1, or any relevant superseded offence. See Archbold or Blackstone for details.<br />

5. Note that the restrictions in <strong>s.41</strong> only relate to defence evidence and questions. In R v<br />

Soroya [2006] EWCA Crim 1884 it was argued that the lack of a similar bar to the<br />

prosecution adducing evidence of previous sexual behaviour breached the right to a<br />

fair trial under Article 6 of the ECHR. The Court of Appeal did not need to deal with<br />

this argument, but expressed the opinion that s.78 of PACE provided sufficient<br />

powers to ensure a fair trial.<br />

Sexual Behaviour (Step 2)<br />

6. Sexual behaviour includes sexual experience. It is construed objectively. The Court of<br />

Appeal in R v E [2004] EWCA Crim 1313 decided that girls of 4 and 6 could engage<br />

in sexual behaviour under the Act, even if they were too young to have any<br />

appreciation that what had occurred was sexual.<br />

7. The restrictions may prevent evidence or questions which raise an inference of sexual<br />

behaviour, if that is their real purpose. This occurs most frequently in the context of<br />

an abortion, especially where the defendant is a family member who gave the<br />

complainant advice or assistance about obtaining a lawful abortion. Such evidence or<br />

questions are not of themselves about sexual behaviour, but they obviously carry the<br />

implication that there has been antecedent sexual behaviour which gave rise to the<br />

pregnancy to be terminated. If there is a genuine reason for the evidence or questions,<br />

unrelated to the antecedent sexual behaviour, they are not caught by <strong>s.41</strong> [R v RP<br />

[2013] EWCA Crim 2331]. In many contexts, however, the evidence or questioning<br />

may simply be a way of attacking the sexual habits of the complainant, in which case<br />

<strong>s.41</strong> does apply [R v PK [2008] EWCA Crim 434].<br />

Facebook<br />

8. Facebook is another fruitful source of evidence and questions where the issue arises<br />

whether the entries amount to evidence of sexual behaviour. In R v Ben-Rejab [2011]<br />

EWCA Crim 1136 the Court of Appeal decided that completing sexual quizzes<br />

amounted to sexual behaviour. As Pitchford LJ said:

Western Circuit RASSO Course 28 <strong>Feb</strong>ruary <strong>2015</strong><br />

Section 41 YJCE Act 1999 – Philip Mott QC<br />

“What motive can there have been when engaging in the<br />

activity of answering sexually explicit questions unless it was<br />

to obtain sexual pleasure from it?”<br />

9. In R v D [2011] EWCA Crim 2305 the Court of Appeal refused leave to adduce fresh<br />

evidence of Facebook entries by the complainant after the rape in which she posed<br />

provocatively but clothed. Rafferty LJ said:<br />

“The complex mixture of motives which impels people,<br />

especially young people, to post messages on such sites<br />

includes, the court suspects, the desire to attract attention,<br />

admiration from peers and to provoke the interest of others in<br />

the person posting the material. We suspect that objective truth<br />

and the dissemination of factual evidence comes low on the list.<br />

In this instance the complainant’s postings can be summarized<br />

as her saying outrageous or provocative things or claiming<br />

daring behaviour on her part. There are many entries, for<br />

example, boasting about how much she drank and the great<br />

hangovers she suffered as a result. In addition, there are claims<br />

of interest in sexual matters. These come much later in the<br />

postings and are to be found at the time of trial. By the<br />

following August she was posting photographs of herself and<br />

of herself with other girls. All the pictures are of the girls<br />

clothed, but provocatively so, no doubt in a way perceived by<br />

her and by them as sexually attractive. Choosing our words<br />

with care, they are images not dissimilar in content and<br />

presentation to what can be seen travelling many an<br />

underground escalator, albeit the model in question here is a<br />

girl in her early teens rather than a grown woman. None of the<br />

postings lays claim to direct sexual activity on the part of the<br />

complainant, though three or four of them indicate that she<br />

thinks quite a lot of the time about her own sexuality and<br />

indeed about having sexual intercourse.”<br />

10. R v T [2012] EWCA Crim 2358 is a difficult case to follow. T was convicted of<br />

raping a 13 year old girl. He sought to adduce in cross-examination of the<br />

complainant a photograph of her in a bikini which he claimed she had sent him via<br />

Facebook around Valentine’s Day. On a voir dire she denied sending the photograph.<br />

The Court of Appeal (Moses LJ, Nicol & Lindblom JJ) adjourned the appeal to allow<br />

the prosecution to investigate the provenance of the photograph. If genuine, it was<br />

relevant to an issue in the case, namely that she had been interested in him but<br />

rejected by him, and thus had a motive to lie, and the judge had no discretion to refuse<br />

leave. It was for the jury to decide whether she had sent it as he claimed but she<br />

denied.<br />

(1) Was this really evidence of “sexual behaviour”, even on the extended definition<br />

accepted in R v Ben-Rejab [2011] EWCA Crim 1136? If not, <strong>s.41</strong> was not even<br />

engaged.<br />

(2) It is difficult to see how this related to a relevant issue, i.e. one which had to be<br />

proved by prosecution or defence. Why should a photograph of the girl in a bikini,

Western Circuit RASSO Course 28 <strong>Feb</strong>ruary <strong>2015</strong><br />

Section 41 YJCE Act 1999 – Philip Mott QC<br />

even if sent to the defendant by her, have any relevance to whether she had sexual<br />

intercourse with him in a park 8 months later? In any event, his defence was not<br />

reasonable belief in consent. He denied sexual intercourse.<br />

(3) At best, this was evidence supporting the assertion that this was a false complaint<br />

motivated by malice or rejection. According to R v DB [2012] EWCA Crim 1235<br />

(decided before but not cited to the court in R v T) motive is not a “relevant issue<br />

in the case” as defined by s.42(1)(a) [see paragraph 32 below].<br />

(4) If it was not a “relevant issue in the case”, <strong>s.41</strong>(3) could not apply and the court<br />

could not grant leave [<strong>s.41</strong>(2)(a)].<br />

(5) If it was a relevant issue, it was not an issue of consent, so <strong>s.41</strong>(3)(a) applied.<br />

Leave would have to be granted, but only if a conclusion of the jury on a relevant<br />

issue (such as guilt) might thereby be rendered unsafe [<strong>s.41</strong>(2)(b)].<br />

(6) As to Facebook, the importance of this decision is the acknowledgement that<br />

defendants can readily obtain images and manipulate them, as well as making<br />

false entries on Facebook pages. See also the discussion in Ormerod and O’Floinn<br />

“Social networking material as criminal evidence” [2012] Crim LR 486.<br />

(7) As a footnote, after the adjournment the appeal was later abandoned by the<br />

appellant.<br />

False complaints<br />

11. False complaints are not sexual behaviour. Being false, no sexual behaviour actually<br />

took place as alleged in the complaint. The difficulty is in judging whether there is<br />

sufficient evidence that a complaint was false for it to go to the jury as such.<br />

12. S.41 will of course apply to the reverse situation, where the complainant has falsely<br />

denied a true previous sexual experience.<br />

13. Where the defendant seeks to adduce evidence or ask questions about an allegedly<br />

false complaint, he must seek a ruling from the judge that <strong>s.41</strong> does not apply, and<br />

also provide a proper evidential basis for the allegation [R v T and H [2001] EWCA<br />

Crim 1877].<br />

(1) There must have been an earlier complaint of a sexual nature. In R v Lefeuvre<br />

[2011] EWCA Crim 1253 there were allegedly false complaints about the theft of<br />

a mobile phone on two occasions, once when she woke up to find herself naked,<br />

but neither of these involved a complaint of sexual assault. On another occasion<br />

someone else complained of an assault in her hall of residence, but she made no<br />

complaint. The final incident was a complaint of a stranger entering her flat and<br />

sexually assaulting her, but there was no evidence that this was false. In R v<br />

Callaghan [2012] EWCA Crim 1669 the complainant had accused her former<br />

husband of assaulting her whilst she was asleep, but when he called the police she<br />

refused to make a complaint.<br />

(2) The earlier complaint must have been false. In R v Winter [2008] EWCA Crim 3<br />

the complainant had told the police that she had a close and loving relationship

Western Circuit RASSO Course 28 <strong>Feb</strong>ruary <strong>2015</strong><br />

Section 41 YJCE Act 1999 – Philip Mott QC<br />

with her partner M, but the following day returned to the police station to explain<br />

that she was also involved in an active sexual relationship with another man S.<br />

The Court of Appeal (Longmore LJ, Beatson & Blake JJ) concluded that the first<br />

statement that she was devoted to M was not a lie merely because she had a sexual<br />

relationship with S, but even if it was a lie it was short-lived and insignificant.<br />

(3) There must be a proper evidential basis for the allegation of falsity. The test is<br />

whether falsity is a reasonable inference to draw, no higher than that [R v E [2005]<br />

Crim LR 227]. The defence advocate cannot seek leave on the basis that the<br />

evidence will come from questioning the complainant, in the hope of showing that<br />

the complaint was false [R v Abdelrahhman [2005] EWCA Crim 1367]. Mere<br />

inconsistencies are not enough, nor is the fact that the police or CPS decided that<br />

there was insufficient evidence to prosecute [R v RD [2009] EWCA Crim 2137].<br />

(4) Lack of cooperation with the police may provide a proper evidential basis for the<br />

allegation of falsity, if the circumstances are stark enough. R v Garaxo [2005]<br />

EWCA Crim 1170 is the high point from a defendant’s viewpoint, and was said in<br />

R v V [2006] EWCA Crim 1901 to have been decided on particular facts. R v AM<br />

[2009] EWCA Crim 618 is the best guide, concerning a case where an allegation<br />

of rape was made only after a housing officer told the complainant that it would<br />

not assist her to be moved unless she reported it to the police. She told the police<br />

that she was only reporting the incident to get rehoused, she did not want it<br />

investigated or taken further, and she would not support a prosecution or attend<br />

court. She said this was because she was scared of repercussions. The Court of<br />

Appeal stressed that such decisions are fact-sensitive, but “the relevant question is<br />

whether that material is capable of leading to a conclusion that the previous<br />

complaint was false”. In that case it was. In R v Hilly [2014] EWCA Crim 1614<br />

even four separate unpursued allegations of sexual abuse against four different<br />

men was insufficient to raise an inference that they were false.<br />

(5) A previous failed prosecution does not provide evidence of falsity. All it means is<br />

that the Crown did not satisfy the criminal burden and standard of proof [R v BD<br />

[2007] EWCA Crim 4; R v Davarifar [2009] EWCA Crim 2294].<br />

(6) The allegation will also be one of bad character, so the provisions of s.100 of the<br />

Criminal Justice Act 2003 will apply.<br />

(7) Care must be taken to ensure that questioning does not become protracted and lead<br />

to the exploration of irrelevant material [R v Lee B [2005] EWCA Crim 3146].<br />

The procedural requirements and powers should be used to prevent this [see<br />

below]<br />

Issue of Consent (Steps 3, 4, 5 & 6)<br />

Not an issue of consent (Step 3)<br />

14. Reasonable belief in consent is not an issue of consent [s.42(1)(b)]. Such a belief must<br />

have existed at the time of the alleged offence. Unless the defendant knew about the<br />

sexual behaviour of the complainant at that time, it is irrelevant to his state of mind.

Western Circuit RASSO Course 28 <strong>Feb</strong>ruary <strong>2015</strong><br />

Section 41 YJCE Act 1999 – Philip Mott QC<br />

15. Note the impact of the SOA 2003, which now requires such a belief to be reasonable,<br />

as well as honestly held (which was the test at the time <strong>s.41</strong> was passed). Honest<br />

belief and reasonable belief are very different things. In R v Bahador [2005] EWCA<br />

Crim 396 the defendant sought to rely on the fact that the complainant had performed<br />

at a club when she bared her breast and simulated oral sex with a man. That could not<br />

reasonably have caused him to believe that she would consent to intercourse with him<br />

after she left the club. In R v Harrison [2006] EWCA Crim 1543 the defendant was<br />

rightly excluded from asking about the complainant having consensual sex with<br />

another man she had met with the defendant in a club and gone with to a house. Three<br />

hours later the complainant woke up to find the defendant digitally penetrating her.<br />

The earlier consensual intercourse with another man could not have given rise to a<br />

reasonable belief that she would consent to his actions whilst she was asleep.<br />

16. An allegation that the complainant is motivated by malice is not an issue of consent.<br />

Thus evidence of a later consensual relationship with the defendant which led to a<br />

desire for revenge would be both relevant and admissible [R v F [2005] 2 Cr App R<br />

13].<br />

17. An allegation that a young complainant’s detailed account could have come from<br />

other sexual experiences is not an issue of consent. Realistically, it should only arise<br />

with very young complainants, where the prosecution case is that the allegations must<br />

be true by reason of a level of detail not to be expected from the imagination of<br />

someone of that age. It does not arise where a 14 year old gives evidence of<br />

masturbation and normal sexual conduct, as it is “almost inevitable” that such<br />

information would be known by that age [R v MF [2005] EWCA Crim 3376].<br />

At or about the same time (Step 4)<br />

18. The window of time is likely to be fairly limited, as a complainant’s responses will<br />

vary from occasion to occasion. Consent is not given once and for all time. Equally,<br />

behaviour with others is unlikely to be relevant and therefore admissible. Such<br />

decisions will be fact-sensitive.<br />

19. R v Mukadi [2004] Crim LR 373 is a difficult case. The Court of Appeal (Mantell LJ,<br />

Sir Edwin Jowett & Recorder of Manchester) decided that cross-examination should<br />

have been allowed about an incident earlier in the same day when the complainant<br />

climbed into an expensive car with an older man in Oxford Street, drove to a filling<br />

station with him and exchanged phone numbers, because this might have led to the<br />

inference that she anticipated that some sexual activity would follow. Quite how this<br />

could have been relevant to the issue of consent to intercourse with a different man<br />

several hours later, after which she jumped out of a window breaking two wrists and a<br />

kneecap, is puzzling! As Professor Di Birch said in the Criminal Law Review<br />

commentary [2004] Crim LR 373:<br />

“… the suggestion may have been that the complainant’s<br />

demeanour was consistent with prostitution – the emphasis on<br />

her dress, the dirty interior of the car (mine would not have<br />

passed muster with the Court of Appeal either, I fear) and the<br />

age of its solitary occupant, together with the business of the<br />

exchange of numbers at the filling station, suggest that this was<br />

no ordinary romantic encounter. But in the absence of any clear

Western Circuit RASSO Course 28 <strong>Feb</strong>ruary <strong>2015</strong><br />

Section 41 YJCE Act 1999 – Philip Mott QC<br />

evidence it would seem improper to draw such an inference and<br />

then to apply it laterally to the complainant’s relationship with<br />

M, who does not appear to have been suggesting that the<br />

relationship was a commercial one.<br />

What is not permissible is for evidence to be adduced on the<br />

basis of ostensible relevance to consent when the real purpose<br />

is to discredit the complainant: <strong>s.41</strong>(4) expressly forbids this<br />

tactic. The reasoning employed in the present case appears to<br />

draw on a dangerous generalisation about consent as an attitude<br />

of mind rather than a choice made on an individualised,<br />

perhaps even capricious, basis. To the extent that the real<br />

purpose might have been, as the trial judge clearly suspected, to<br />

discredit the complainant, the evidence was doubly damned.”<br />

It is now generally accepted to be a ‘rogue’ decision.<br />

So similar (Step 5)<br />

20. The similarity must be particular and unusual. Going to the same hotel as one visited<br />

previously for a one night stand is not enough [R v X [2005] EWCA Crim 2995].<br />

21. In R v Harris [2009] EWCA Crim 434 the defendant was a homeless man picked up<br />

by the complainant and taken back to her flat where they got drunk together. She<br />

alleged that he detained her there by threats, assaulted and raped her. Medical records<br />

showed that she had a history of casual sex with illegal taxi drivers, drinking alcohol<br />

excessively and engaging in risky sexual liaisons. She described a wish to punish<br />

herself. She said the notes misrepresented the history she had given medical staff. The<br />

defendant was not allowed to adduce this evidence, as it was tantamount to saying<br />

that the complainant was a person who had engaged in casual sex in the past and<br />

therefore would have been likely to do so with the defendant. The Court of Appeal<br />

upheld this decision as being one open to the judge as the primary decision maker.<br />

22. One example of sufficient similarity is R v T [2004] 2 Cr App R 551. Both the event<br />

charged and the previous incident involved having sex inside a metal climbing frame<br />

in a children’s playground in a rather specific sexual position. The trial judge refused<br />

the application for leave, but the Court of Appeal allowed the appeal. The previous<br />

incident was 3-4 weeks earlier, but the Court of Appeal said it was probable that there<br />

was no requirement that the temporal link should be particularly close. In any event,<br />

the application should have been dealt with under <strong>s.41</strong>(3)(c)(i), not <strong>s.41</strong>(3)(c)(ii), so<br />

that the temporal requirement did not apply.<br />

23. Note that the similarity is to be judged “according to the evidence adduced or to be<br />

adduced by or on behalf of the accused” [<strong>s.41</strong>(3)(c)(i)]. Even if there is no<br />

independent evidence in support it should be assumed to be true for the purpose of<br />

granting or refusing leave. It is for the jury to assess whether or not it is or may be<br />

true, and what weight to give to the evidence.

Western Circuit RASSO Course 28 <strong>Feb</strong>ruary <strong>2015</strong><br />

Section 41 YJCE Act 1999 – Philip Mott QC<br />

Impugning credibility (Step 6)<br />

24. Evidence or questions, even if satisfying one of the gateways in <strong>s.41</strong>(3), must be<br />

excluded if the purpose (or main purpose) is to impugn the credibility of the<br />

complainant [<strong>s.41</strong>(4)]. In R v Martin [2004] EWCA Crim 916 the Court of Appeal<br />

concluded that cross-examination should have been allowed where impugning the<br />

credibility of the complainant was a purpose, but only one of the purposes. The<br />

incident had occurred a few days earlier when the defendant had stayed the night at<br />

the complainant’s flat and claimed that he had rejected her advances. It was enough<br />

that the questioning would strengthen the defendant’s case and enhance his own<br />

credibility.<br />

25. Evidence which seeks to demonstrate a malicious motive falls within the gateway in<br />

<strong>s.41</strong>(3)(a), but will always involve an attack on the complainant’s credibility. In R v F<br />

[2005] 2 CR App R 13 this was acknowledged, but for the purposes of <strong>s.41</strong>(4) it did<br />

not necessarily follow that it was the main purpose of the evidence or questions.<br />

Evidence adduced by the prosecution (Step 7)<br />

26. S.41(5) only applies if the evidence is adduced by the prosecution. As a result:<br />

(1) It does not assist the defendant if it is in a complainant’s statement or ABE<br />

interview but not introduced in evidence in chief.<br />

(2) It does not assist the defendant if the evidence is given in answer to questions in<br />

cross-examination. But the Court of Appeal in R v Hamadi [2007] EWCA Crim<br />

3048 indicated that the provision might have to be read more broadly to allow the<br />

defendant to rebut evidence given by a complainant in cross-examination where it<br />

was not deliberately elicited by defence counsel and the evidence was potentially<br />

damaging to the defence case.<br />

27. There have been concerns expressed about the imbalance between prosecution and<br />

defence, and its effect on the fairness of the trial process. The Court of Appeal has<br />

suggested in R v Soroya [2006] EWCA Crim 1884 that this can be dealt with by using<br />

the judge’s powers under s.78 of PACE.<br />

28. There have also been concerns expressed because a defendant may have no evidence<br />

to rebut such evidence adduced by the Crown, and no ability to find such evidence.<br />

The eliciting of positive evidence by the Crown will give rise to a heavy burden of<br />

disclosure in relation to the complainant’s sexual history, and may well dissuade most<br />

prosecutors from using the unrestricted power to do so.<br />

Specific instances (Step 8)<br />

29. S.41(6) prevents the defendant adducing general evidence of reputation, or asking<br />

questions which are not directed to specific instances of sexual behaviour.

Western Circuit RASSO Course 28 <strong>Feb</strong>ruary <strong>2015</strong><br />

Section 41 YJCE Act 1999 – Philip Mott QC<br />

30. Likewise, questions about sexual orientation will usually be disallowed. It is no more<br />

likely that a homosexual man would have consented to sexual activity with a man<br />

with whom he was not in a relationship, just because he was homosexual, than that a<br />

heterosexual woman would consent to sex with a previously unknown man, just<br />

because she was heterosexual.<br />

Rendering unsafe a conclusion of the jury (Step 9)<br />

31. S.41(2) provides a final hurdle. Before leave is granted, the judge must be satisfied<br />

that to refuse it might render unsafe a conclusion of the jury on a relevant issue in the<br />

case. Since “relevant issue in the case” is defined by s.42(1)(a) as limited to an issue<br />

to be proved by prosecution or defence, it is likely to exclude evidence of motive.<br />

32. In R v DB [2012] EWCA Crim 1235 the complainant had run away from home and<br />

complained to police that her father had raped her throughout her childhood. The<br />

defendant was refused leave to cross-examine her about her alleged relationship with<br />

a much older man. This might have provided a motive for her running away from<br />

home, but not for making up allegations against her father. The Court of Appeal<br />

thought it “highly questionable whether an issue of motive can be said to constitute an<br />

issue in the case as defined in section 42(1)(a)”. Contrast this with R v T [2012]<br />

EWCA Crim 2358 [see paragraph 10 above].<br />

Procedure (Step 10)<br />

33. Part 36 of the Criminal Procedure Rules applies. It requires an application in writing<br />

which must –<br />

(1) Identify the issue to which the defendant says the complainant’s sexual behaviour<br />

is relevant;<br />

(2) Give particulars of –<br />

i) Any evidence that the defendant wants to introduce, and<br />

ii)<br />

Any questions that the defendant wants to ask;<br />

(3) Identify the exception to the prohibition in section 41 of the Youth Justice and<br />

Criminal Evidence Act 1999 on which the defendant relies; and<br />

(4) Give the name and date of birth of any witness whose evidence about the<br />

complainant’s sexual behaviour the defendant wants to introduce.<br />

34. These are very useful powers, which will allow a judge to be clear about the nature<br />

and relevance of the application, and to deliver a ruling which covers all the points<br />

raised. They also allow a judge to require a list of questions, and to allow some but<br />

disallow others, thus ensuring that any questioning about previous sexual behaviour is<br />

limited and not oppressive. Judges are encouraged to insist on this, even when an<br />

application is made late and the notice has to be handwritten.

Western Circuit RASSO Course 28 <strong>Feb</strong>ruary <strong>2015</strong><br />

Section 41 YJCE Act 1999 – Philip Mott QC<br />

35. However, failure to follow the procedure in the Rules does not give the judge a<br />

discretion to exclude evidence or questions which must be allowed under <strong>s.41</strong>. The<br />

judge could only adjourn to allow the rules to be complied with and the prosecution to<br />

make enquiries, as in R v T [2012] EWCA Crim 2358.<br />

Philip Mott QC<br />

28 <strong>Feb</strong>ruary <strong>2015</strong>