Pathways of movement for Phytophthora ramorum, the causal agent ...

Pathways of movement for Phytophthora ramorum, the causal agent ...

Pathways of movement for Phytophthora ramorum, the causal agent ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Davidson, J. M., and Shaw, C. G. 2003. <strong>Pathways</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>movement</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Phytophthora</strong> <strong>ramorum</strong>, <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>causal</strong> <strong>agent</strong> <strong>of</strong> Sudden Oak Death. Sudden Oak Death Online Symposium.<br />

www.apsnet.org/online/SOD (website <strong>of</strong> The American Phytopathological Society). doi:10.1094/SOD-2003-TS<br />

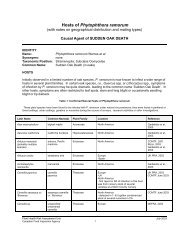

<strong>Pathways</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>movement</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Phytophthora</strong><br />

<strong>ramorum</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>causal</strong> <strong>agent</strong> <strong>of</strong> Sudden Oak<br />

Death<br />

Jennifer M. Davidson and Charles G. (Terry) Shaw<br />

<strong>Phytophthora</strong> <strong>ramorum</strong> and <strong>the</strong> suite <strong>of</strong> diseases it causes,<br />

including Sudden Oak Death, are relatively new to science. As<br />

such, <strong>the</strong>re are far more questions than answers regarding nearly<br />

all aspects <strong>of</strong> this pathogen's biology. However, since <strong>the</strong><br />

discovery <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong> 3 years ago, much has been learned<br />

about <strong>the</strong> transmission biology <strong>of</strong> this pathogen, especially in oak<br />

woodlands.<br />

BACKGROUND<br />

<strong>Phytophthora</strong> species have been studied <strong>for</strong> nearly 150 years, so<br />

extensive background knowledge exists on <strong>the</strong> transmission<br />

biology <strong>of</strong> this genus. In general, <strong>Phytophthora</strong> species that infect<br />

aerial parts <strong>of</strong> plants spread through a cycle <strong>of</strong> production <strong>of</strong><br />

sexual, or more <strong>of</strong>ten, asexual spores, <strong>movement</strong> <strong>of</strong> spores, and<br />

infection <strong>of</strong> new host tissue. The new infection can <strong>the</strong>n serve as<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r source <strong>of</strong> spores to begin <strong>the</strong> cycle again. Appropriate<br />

environmental conditions (temperature and relative humidity), as<br />

well as survival <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> pathogen (ei<strong>the</strong>r as spores or mycelia), are<br />

necessary <strong>for</strong> each step <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cycle. Transport <strong>of</strong> infected host<br />

tissue harboring a viable pathogen can also introduce<br />

<strong>Phytophthora</strong> to new areas where <strong>the</strong> pathogen may establish if it<br />

can complete <strong>the</strong> cycle described above.<br />

The first step, production <strong>of</strong> spores, occurs on or within living<br />

plant tissue. P. <strong>ramorum</strong> has thus far only been found to infect<br />

aerial parts <strong>of</strong> plants, including leaves, green stems, and woody<br />

stems, but not roots. At 15 - 20 ºC, in culture and on foliar hosts<br />

such as bay and rhododendron, P. <strong>ramorum</strong> readily <strong>for</strong>ms<br />

sporangia that are highly deciduous, a characteristic consistent<br />

with dispersal from aboveground plant parts. Both attached and<br />

detached sporangia <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong> produce zoospores (asexual<br />

spores) in culture. In addition, P. <strong>ramorum</strong> prolifically produces<br />

chlamydospores (asexual spores) in culture and on some foliar<br />

hosts, indicating a possible mechanism <strong>for</strong> dormancy and survival<br />

in adverse conditions. Oospores (sexual spores) have not been<br />

observed in nature, perhaps because P. <strong>ramorum</strong> appears to<br />

require two mating types to produce sexual spores. Currently, <strong>the</strong><br />

European population only has one mating type, and <strong>the</strong> North<br />

American population has <strong>the</strong> opposite mating type.<br />

Once spores are produced by aboveground <strong>Phytophthora</strong> species,

<strong>the</strong>y are commonly dispersed through several mechanisms 2 , 3 .<br />

Often <strong>the</strong> spores are splashed or carried to <strong>the</strong> ground by rain or<br />

sprinkler drops. Spores landing in streams or irrigation run<strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong>n<br />

potentially can travel long distances. Likewise, spores landing in<br />

<strong>the</strong> soil <strong>of</strong> a <strong>for</strong>est or nursery floor can be transported in soil<br />

sticking to shoes, equipment, or vehicles. For a few <strong>Phytophthora</strong><br />

species, such as P. infestans, sporangia are dispersed in air<br />

without water drops (e.g., without rain, sprinklers). Finally, spores<br />

and hyphae may be spread through <strong>movement</strong> <strong>of</strong> infected plant<br />

material. As described below, spores <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong>, like spores <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> aboveground <strong>Phytophthora</strong> species, are known to<br />

move via all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se mechanisms except dispersal in air without<br />

water drops.<br />

A final step in <strong>the</strong> reproductive cycle involves successful infection<br />

<strong>of</strong> new host tissue. Reaching a susceptible host is essential. In<br />

addition, preliminary studies indicate that optimal infection <strong>of</strong> bay<br />

leaves by zoospores <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong> occurs at 20° C. A film <strong>of</strong><br />

water on <strong>the</strong> leaves <strong>for</strong> 12 hours appears to be necessary <strong>for</strong><br />

infection by P. <strong>ramorum</strong> (D. Huberli, unpublished data).<br />

PATHWAYS<br />

Research to determine each component <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> transmission cycle<br />

<strong>for</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong> will allow us to better evaluate possible pathways<br />

<strong>for</strong> pathogen spread. These pathways include transmission in<br />

natural ecosystems and spread through human activities such as<br />

commerce and recreation. Below, we present brief summaries<br />

characterizing pathways <strong>for</strong> both <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se main areas. The concern<br />

is basic - <strong>movement</strong> <strong>of</strong> spores or infected plants may serve as a<br />

pathway <strong>for</strong> pathogen spread. What do we know about <strong>the</strong><br />

mechanisms and potential <strong>for</strong> this <strong>movement</strong> to actually happen?<br />

<strong>Pathways</strong> in natural ecosystems.<br />

The life cycle <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong> and mechanisms <strong>of</strong> spread have been<br />

studied in coast live oak and tanoak woodlands in nor<strong>the</strong>rn<br />

Cali<strong>for</strong>nia. Although all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> host species (currently, <strong>the</strong>re are<br />

more than 20) have not been examined, dominant hosts such as<br />

coast live oak, tanoak, coast redwood, and bay are being tested<br />

<strong>for</strong> spore production. A major source <strong>of</strong> spores in <strong>the</strong>se <strong>for</strong>ests<br />

appears to be infected bay leaves 1 . To date, sporulation has not<br />

been observed on intact bark <strong>of</strong> oak or tanoak trunks. Studies are<br />

underway to determine whe<strong>the</strong>r sporulation occurs on tanoak and<br />

redwood leaves and small branches.<br />

Once spores are <strong>for</strong>med in <strong>the</strong>se <strong>for</strong>ests, rain carries <strong>the</strong>m onto<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r plants, into streams, or onto soil 1 . P. <strong>ramorum</strong> has been<br />

detected in streams throughout <strong>the</strong> rainy season, and in some<br />

cases, throughout <strong>the</strong> dry summer months (Davidson, P. Maloney,<br />

S. Tjosvold, unpublished data). However, it is unknown whe<strong>the</strong>r<br />

spores can move from stream water up to infect new plant tissue.<br />

Given that infection patterns in <strong>for</strong>ests do not seem to follow<br />

stream courses, this may be a rare event. P. <strong>ramorum</strong> has also

een detected in soil during <strong>the</strong> rainy, winter months. Hikers have<br />

been shown to carry <strong>the</strong> spores <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong> on <strong>the</strong>ir shoes as<br />

<strong>the</strong>y leave infested tanoak-redwood <strong>for</strong>ests (S. Tjosvold,<br />

unpublished data). In addition, soil from car and mountain bike<br />

tires has tested positive <strong>for</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong> after <strong>the</strong>se vehicles<br />

traveled on dirt roads through infested <strong>for</strong>ests (S. Tjosvold,<br />

unpublished data). It is likely that woodland animals such as deer<br />

also carry spores in soil stuck to <strong>the</strong>ir feet. Laboratory<br />

experiments indicate that inoculum in soil can infect green leaf<br />

litter, which can <strong>the</strong>n transmit P. <strong>ramorum</strong> to aerial plant parts via<br />

rainsplash (Davidson, unpublished data).<br />

While <strong>the</strong>se pathways provide evidence to explain <strong>the</strong> rapid<br />

spread <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong> within a <strong>for</strong>ested site, <strong>the</strong> mechanisms<br />

underlying long-distance jumps <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong>-- <strong>for</strong> example over<br />

250 km from Redway, Cali<strong>for</strong>nia to Brookings, Oregon-- are still<br />

unidentified. Clearly, long-distance transport <strong>of</strong> infested soil via<br />

shoes, vehicles, or equipment may be one route <strong>of</strong> possible longdistance<br />

spread. Anecdotal evidence from nor<strong>the</strong>rn Cali<strong>for</strong>nia<br />

suggests that landscaping with infected horticultural plants at<br />

homes within woodlands adjacent to public wildlands may have<br />

introduced P. <strong>ramorum</strong> to new areas. Studies are underway to<br />

investigate <strong>the</strong> potential role <strong>of</strong> birds in moving spores over longdistance<br />

flight patterns. To date, wind dispersal <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong><br />

without rain has not been demonstrated.<br />

<strong>Pathways</strong> <strong>of</strong> spread through human activity.<br />

Nursery stock. Although <strong>the</strong>re are numerous nursery hosts,<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation on transmission <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong> is best known <strong>for</strong><br />

rhododendron, typically one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most susceptible plant genera<br />

to <strong>Phytophthora</strong>. P. <strong>ramorum</strong> has been isolated from<br />

rhododendrons in nurseries in <strong>the</strong> U.S. (Cali<strong>for</strong>nia) and Europe.<br />

The Cali<strong>for</strong>nia Department <strong>of</strong> Agriculture has traced pathogen<br />

transmission from one nursery to ano<strong>the</strong>r on rhododendron stock.<br />

In Europe, P. <strong>ramorum</strong> was introduced to Majorca, Spain via a<br />

shipment <strong>of</strong> infected rhododendrons, and many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> infections<br />

found in nurseries in <strong>the</strong> United Kingdom can be traced to plant<br />

transport from o<strong>the</strong>r nurseries. P. <strong>ramorum</strong> sporulates prolifically<br />

from rhododendron leaves, producing both sporangia on <strong>the</strong> leaf<br />

and chlamydospores on or within <strong>the</strong> leaf (D. Rizzo, P. Tooley,<br />

unpublished data) (Figure 1a, b). Detached rhododendron leaves<br />

that were dried <strong>for</strong> up to 3 months still produced sporangia upon<br />

wetting (D. Rizzo, unpublished data). In laboratory inoculation<br />

experiments, infection spread from one rhododendron leaf to<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r via water drops that presumably carried sporangia or<br />

zoospores (D. Rizzo, unpublished data). P. <strong>ramorum</strong> has been<br />

isolated from irrigation water from an infested rhododendron<br />

nursery 4 ; (S. Tjosvold, unpublished data). Fungicides commonly<br />

used to control o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Phytophthora</strong> species on rhododendron may<br />

mask symptoms <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong>, making visual diagnosis difficult.<br />

In addition, in infested nurseries, soil or mulch in <strong>the</strong> pots <strong>of</strong><br />

rhododendron plants, o<strong>the</strong>r host plants, and even unsusceptible<br />

plants may contain spores <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong> although <strong>the</strong> plants<br />

appear healthy.

Figure 1a. Sporangia are readily produced on susceptible rhododendron<br />

leaves.<br />

Figure 1b. Chlamydospores are also produced on susceptible rhododendron<br />

leaves.<br />

Bark and wood products. P. <strong>ramorum</strong> has been isolated from<br />

external cankers on stems <strong>of</strong> oaks and tanoaks, including cankers<br />

on fallen trees. Sporulation has occurred from flooded chips <strong>of</strong><br />

infected tanoak and <strong>the</strong> flooded, cut edges <strong>of</strong> coast live oak<br />

cankers, indicating that mulch or firewood may be infective<br />

(Davidson, E. Hansen, unpublished data) (Figure 2). However,<br />

sporulation has not been observed on <strong>the</strong> outside, intact bark <strong>of</strong><br />

infected oak or tanoak logs. On oak, <strong>the</strong> pathogen has been<br />

recovered 3 cm into <strong>the</strong> wood (D. Rizzo, unpublished data).<br />

There<strong>for</strong>e, debarking is not a sufficient treatment to eradicate <strong>the</strong><br />

pathogen from oak wood. It is unclear, however, if <strong>the</strong> pathogen<br />

is infective directly from <strong>the</strong> surface <strong>of</strong> exposed wood. Heating<br />

and drying are recommended as a treatment to destroy P.<br />

<strong>ramorum</strong> in <strong>the</strong>se hardwood species. However, studies are needed<br />

to determine if chlamydospores are produced in bark (phloem)

and wood (xylem), and if so, whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>se spores are destroyed<br />

by drying. Techniques should be developed to assess dormancy<br />

(viability) versus death <strong>of</strong> chlamydospores. Acorns do not appear<br />

to be infected in <strong>the</strong> field, although spores may land on <strong>the</strong><br />

outside <strong>of</strong> acorns. To date, P. <strong>ramorum</strong> has not been found to<br />

infect <strong>the</strong> main trunk <strong>of</strong> Douglas-fir or coast redwood. Studies are<br />

underway to determine if redwood bark mulch contains spores<br />

that may have landed on <strong>the</strong> outside <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bark while <strong>the</strong> tree<br />

was standing in an infested <strong>for</strong>est. Soil on felled trees or logging<br />

equipment from infested <strong>for</strong>ests may also contain spores.<br />

Figure 2. Hyphae <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong> extend from <strong>the</strong> cut edge <strong>of</strong> a coast live oak<br />

canker into water in a laboratory container. A similar process may occur if<br />

infested firewood or chopped logs are stored in areas where water puddles.<br />

Hyphae and spores <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong> have not been observed on <strong>the</strong> outer<br />

surface <strong>of</strong> intact bark <strong>of</strong> coast live oak or tanoak cankers.<br />

Garlands, wreaths, and Christmas trees. Leaves and branches<br />

<strong>of</strong> hosts such as bay laurel, Douglas-fir, and redwood are used in<br />

wreaths and garlands. Douglas-fir is farmed <strong>for</strong> Christmas trees.<br />

Some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se <strong>for</strong>est products are grown or manufactured within<br />

infested counties in Cali<strong>for</strong>nia and previously have been sold<br />

throughout <strong>the</strong> United States. As mentioned above, P. <strong>ramorum</strong><br />

readily sporulates from bay leaves under moist, temperate<br />

conditions. In addition, chlamydospores are <strong>for</strong>med in and on bay<br />

leaves. Any treatment to kill P. <strong>ramorum</strong> in bay leaves would need<br />

to destroy chlamydospores. Again, it is crucial to be able to<br />

determine whe<strong>the</strong>r chlamydospores are dormant or dead. P.<br />

<strong>ramorum</strong> infects <strong>the</strong> small branches <strong>of</strong> Douglas-fir and small<br />

branches and needles <strong>of</strong> redwood. Studies are underway to<br />

examine sporulation on <strong>the</strong>se two important economic hosts. Even<br />

without sporulation, fir wreaths and Christmas trees could serve<br />

as an infection pathway if hyphae were able to grow from infected<br />

branch tips and needles. Cones <strong>of</strong> redwood and Douglas-fir do not<br />

appear to be infected in <strong>the</strong> field, although spores may land on<br />

<strong>the</strong> outside <strong>of</strong> cones.

Greenwaste/compost. Greenwaste containing host material<br />

from infested areas may serve as a source <strong>of</strong> spores, especially<br />

from leaves <strong>of</strong> foliar hosts. Even with green material dried <strong>for</strong><br />

several months, some plant tissue, such as rhododendron leaves,<br />

will still sporulate upon wetting. Although it has not been<br />

demonstrated, it is likely that spores could be dispersed from<br />

foliar hosts via rainsplash during transit in open containers, or<br />

that infected leaves could detach and blow away. Tests indicate<br />

that P. <strong>ramorum</strong> in greenwaste mulch is killed in compost after<br />

being held at 55° C <strong>for</strong> 2 weeks (M. Garbelotto, S. Swain, T.<br />

Harnik, K. Hayden, unpublished data).<br />

Recreation and tourism. Spores <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong> have been<br />

detected on <strong>the</strong> shoes <strong>of</strong> hikers and on <strong>the</strong> tires <strong>of</strong> mountain bikes<br />

and vehicles used on dirt roads or trails in an infested tanoakredwood<br />

park in Santa Cruz County, Cali<strong>for</strong>nia. Subsequent<br />

outings to o<strong>the</strong>r natural areas by <strong>the</strong>se visitors may <strong>the</strong>n spread<br />

<strong>the</strong> pathogen via infested soil. In this same study, a survey <strong>of</strong><br />

those visitors with infected shoes showed that many people<br />

leaving <strong>the</strong> park were going to o<strong>the</strong>r parts <strong>of</strong> Cali<strong>for</strong>nia, <strong>the</strong> United<br />

States, and Europe (S. Tjosvold, unpublished data). In infested<br />

park and recreation areas, educational signs coupled with a place<br />

to wash soil from shoes and equipment would help lower <strong>the</strong><br />

probability <strong>of</strong> spread via park visitors. For popular destinations,<br />

taking <strong>the</strong>se steps may be more realistic than attempting to close<br />

infested areas during <strong>the</strong> rainy season.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

<strong>Pathways</strong> <strong>of</strong> spread in commerce mirror <strong>the</strong> pathways <strong>of</strong> spread in<br />

natural ecosystems, with <strong>the</strong> major difference being that, in trade<br />

pathways, more infected plant material is transported over<br />

greater distances, increasing <strong>the</strong> potential to introduce P.<br />

<strong>ramorum</strong> to new geographic areas. Background knowledge on <strong>the</strong><br />

transmission biology <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>Phytophthora</strong> species as well as data<br />

on <strong>the</strong> spread <strong>of</strong> P. <strong>ramorum</strong> in natural ecosystems can give us<br />

insight into <strong>the</strong> way P. <strong>ramorum</strong> may spread in trade pathways.<br />

Containment is important. Given <strong>the</strong> wide host range <strong>of</strong> P.<br />

<strong>ramorum</strong>, it is likely that this pathogen could establish itself in<br />

new geographic areas and cause <strong>the</strong> substantial <strong>for</strong>est destruction<br />

that we are now witnessing in Cali<strong>for</strong>nia.<br />

LITERATURE CITED<br />

1. Davidson J. M., Rizzo D. M., Garbelotto M., Tjosvold S.,<br />

Slaughter G. W. 2002. <strong>Phytophthora</strong> <strong>ramorum</strong> and Sudden<br />

Oak Death in Cali<strong>for</strong>nia: II. Transmission and Survival. In<br />

Proceedings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Fifth Symposium on Oak Woodlands:<br />

Oak Woodlands in Cali<strong>for</strong>nia's Changing Landscape. 2001<br />

October 22-25; San Diego, CA. General Technical Report<br />

PSW-GTR-184, ed. R. B. Standi<strong>for</strong>d, D. McCreary, K. L.<br />

Purcell, pp. 741-9. Albany, CA: Pacific Southwest Research<br />

Station, USDA Forest Service, U.S. Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Agriculture.<br />

2. Erwin D. C., Ribeiro O. K. 1996. <strong>Phytophthora</strong> Diseases

Worldwide. St. Paul, MN: APS Press. 562 pp.<br />

3. Ristaino J. B., Gumpertz M. L. 2000. New frontiers in <strong>the</strong><br />

study <strong>of</strong> dispersal and spatial analysis <strong>of</strong> epidemics caused<br />

by species in <strong>the</strong> genus <strong>Phytophthora</strong>. Annual Review <strong>of</strong><br />

Phytopathology 38: 541-76.<br />

4. Werres S., Marwitz R., Man in't Veld W. A., De Cock A. W.<br />

A. M., Bonants P. J. M., et al. 2001. <strong>Phytophthora</strong> <strong>ramorum</strong><br />

sp. nov., a new pathogen on Rhododendron and Viburnum.<br />

Mycological Research 105: 1155-65.