Spring 2003 | Issue 6

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

A Newsletter from the American Academy in Berlin | Number Six | <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2003</strong><br />

The BerlinJournal<br />

America:<br />

The Ambivalent<br />

Empire?<br />

Michael Ignatieff<br />

Josef Joffe<br />

Hans-Ulrich Wehler<br />

David Rieff<br />

Plus:<br />

Jeffrey Eugenides<br />

Alex Ross and Kent Nagano<br />

Amity Shlaes<br />

Fritz Stern<br />

Paul Volcker

Schering<br />

C3<br />

American Academy

The BerlinJournal<br />

Number Six | <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2003</strong><br />

In These Times<br />

Berlin has seen many changes since its Wall fell in<br />

1989, but the recent shift in attitude toward America<br />

has been particularly jarring. As historians will<br />

remind us, Europe has a distinguished tradition of<br />

looking askance at American cultural, political, and<br />

economic practices. But, for fifty years, Berliners harbored<br />

a special affection for America. Now, in the<br />

city once kept free by the airlift, a new atmosphere of<br />

discomfort and even resentment about the US exercise<br />

of power abroad seems to have taken hold. At a<br />

time when attacks on the administration’s foreign<br />

policy are conflated with polemics about Americans<br />

in general, the presence of a dozen or more American<br />

scholars, policy experts, and artists just a short drive<br />

from the Bundestag has proven invaluable.<br />

The seasoned negotiator Richard Holbrooke<br />

predicted in the Academy’s founding tractate that<br />

this institution would become “a unique meeting<br />

place for the post-cold-war generation of American<br />

and German intellectual, cultural, and political<br />

leaders.” And indeed it has. Fellows find themselves<br />

repeatedly in the shoes of cultural ambassadors.<br />

In the breadth of their views, they embody what<br />

Hans-Ulrich Wehler and Fritz Stern in these pages<br />

admiringly call the American genius for constructive<br />

self-criticism.<br />

Thus this spring, some fellows met privately with<br />

politicians including Angela Merkel and Friedrich<br />

Merz of the cdu, Interior Minister Otto Schily (spd),<br />

and Jürgen Trittin and Rezzo Schlauch of the Greens.<br />

The Hans Arnhold Center’s well-attended array of<br />

public programs was supplemented by out-of-house<br />

panel discussions with ngos, church groups, and<br />

radio and television audiences. Fellows published<br />

articles and interviews in the German press.<br />

However ideologically fraught the debate on<br />

American power has been in certain sectors of Berlin<br />

and Washington, high priority is given in traditional<br />

Atlanticist quarters to reestablish a common agenda.<br />

The pessimism of many pundits is unwarranted: as<br />

dramatic as the transatlantic rift may seem, it may, in<br />

the end prove to be therapeutic in forcing clarity<br />

about our relations and institutions such as the<br />

Security Council.<br />

Long before the statues of Saddam toppled in<br />

Baghdad, cautionary words about “empire” were<br />

on the lips of many. In the hopes of bringing a sober<br />

appraisal to bear on current events, we invited four<br />

experts to reflect on the pitfalls and promises of the<br />

American empire. And we also made room for the<br />

poetry, portraits, art, and lively writing that make<br />

each issue of the Berlin Journal something more. All<br />

of this should remind readers of the extent to which<br />

the US and Germany remain culturally, economically<br />

and historically intertwined.<br />

Gary Smith<br />

Paul Volcker discusses<br />

current corporate<br />

practices and the urgent<br />

need for reform.<br />

Is America Ambivalent<br />

About Empire?<br />

We asked four experts.<br />

Alex Ross interviews<br />

Kent Nagano about his<br />

friendship with composer<br />

Olivier Messiaen.<br />

Historian Fritz Stern<br />

cautions against the<br />

misappropriation of<br />

history.<br />

Amity Shlaes describes<br />

the commodity curse and<br />

explains why riches sometimes<br />

harm, not help.<br />

Pulitzer Winner Jeffrey<br />

Eugenides searches for<br />

history beneath the Hans<br />

Arnhold Center.<br />

3<br />

8<br />

33<br />

38<br />

40<br />

Plus<br />

Paul Volcker chairs the<br />

Trustees of the International<br />

Accounting Standards<br />

Committee Foundation.<br />

He served as chairman of the<br />

Board of Governors of the<br />

Federal Reserve System from<br />

1979 to 1987 and headed the<br />

New York Federal Reserve<br />

Bank between 1975 and 1979.<br />

He has taught economics at<br />

Princeton and nyu. Last fall<br />

he delivered the first annual<br />

Stephen Kellen Lecture, which<br />

also launched the Academy’s<br />

JPMorgan Policy Briefs.<br />

Michael Ignatieff is director<br />

of the Carr Center for Human<br />

Rights Practice at Harvard’s<br />

Kennedy School of Government.<br />

Josef Joffe is editor and<br />

publisher of Die Zeit and a<br />

trustee of the American<br />

Academy in Berlin. Hans-<br />

Ulrich Wehler is professor of<br />

history at the Universität<br />

Bielefeld. Haniel Fellow<br />

David Rieff is the author, most<br />

recently, of A Bed for the Night:<br />

Humanitarianism in Crisis.<br />

Alex Ross is the New Yorker’s<br />

music critic and was<br />

Holtzbrinck Fellow at the<br />

American Academy in Berlin<br />

last fall. His book on the history<br />

of twentieth-century<br />

music will be published<br />

next year. Kent Nagano is<br />

chief conductor and artistic<br />

director of the Deutches<br />

Symphonie-Orchester Berlin,<br />

leads the Berkeley Symphony,<br />

and is principle conductor at<br />

the Los Angeles Opera.<br />

Fritz Stern, emeritus professor<br />

of history at Columbia<br />

University and a founding<br />

trustee of the American<br />

Academy in Berlin, is author,<br />

most recently, of Dreams and<br />

Delusions: The Drama of<br />

German History and Einstein’s<br />

German World. This spring,<br />

an annual lecture series at the<br />

Academy was inaugurated<br />

in his honor. Reinhard Meier<br />

is an editor at the<br />

Neue Zürcher Zeitung.<br />

Amity Shlaes holds the<br />

JPMorgan International Prize<br />

in Finance this spring. She is<br />

a senior columnist on political<br />

economy at the Financial<br />

Times. Her recent book The<br />

Greedy Hand: How Taxes Drive<br />

Americans Crazy and What to<br />

Do About it was a US national<br />

bestseller. Her first book,<br />

Germany: The Empire Within,<br />

explored German national<br />

identity at the end of the<br />

cold war.<br />

August Kleinzahler offers a<br />

poem; Newsweek’s Europe editor<br />

Michael Meyer profiles<br />

Academy trustee Karl von der<br />

Heyden; writer Christine<br />

Brinck lends an ear to<br />

Ambassador Richard<br />

Holbrooke for Die Zeit;<br />

scholar Hayden White’s new<br />

project; and the best<br />

springtime news about the<br />

American Academy in Berlin,<br />

its visitors, friends, alumni,<br />

and current fellows.<br />

A Newsletter from the<br />

American Academy in Berlin<br />

Published semi-annually at the<br />

Hans Arnhold Center<br />

Number Six – <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2003</strong><br />

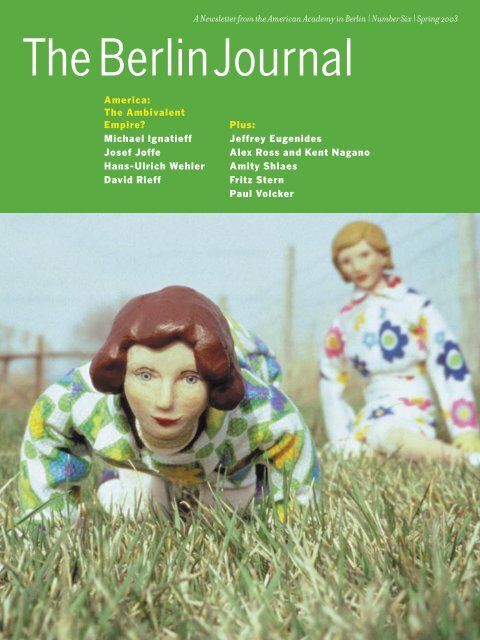

Cover:<br />

Karen Yasinsky, dvd projection<br />

still from the animation<br />

“still life w/cows,” 2000.<br />

T HE<br />

A M E R IC A N<br />

AC ADE M Y<br />

I N B E R LIN<br />

Hans Arnhold Center<br />

Editor<br />

Gary Smith<br />

Associate Editor<br />

Miranda Robbins<br />

Design<br />

Susanna Dulkinys and<br />

Erik Spiekermann,<br />

United Designers<br />

Managing Editor<br />

Teresa Go<br />

Original Drawings<br />

Ben Katchor<br />

Advertising<br />

Renate Pöppel<br />

Translations<br />

Daniel Huyssen<br />

The American Academy in Berlin<br />

Am Sandwerder 17–19<br />

14109 Berlin<br />

Tel. (+ 49 30) 80 48 3-0<br />

Fax (+ 49 30) 80 48 3-111<br />

Email: journal@americanacademy.de<br />

The Berlin Journal is funded entirely<br />

through advertising and tax-deductible<br />

donations. Contributions are very<br />

much appreciated, either by check<br />

or by bank transfer to:<br />

American Academy in Berlin<br />

Berliner Sparkasse, Account no.<br />

660 000 9908, BLZ 100 500 00<br />

All rights reserved ISSN 1610-6490<br />

Executive Director<br />

Gary Smith<br />

Deputy Director<br />

Paul Stoop<br />

Development Director<br />

Anne-Marie McGonnigal<br />

External Affairs Director<br />

Renate Pöppel<br />

Fellows Services Director<br />

Marie Unger<br />

Program Coordinator<br />

Ute Zimmermann<br />

Press Coordinator<br />

Ingrid Müller<br />

Fellows Selection<br />

Coordinator<br />

Lily Saint<br />

Trustees of the<br />

American Academy<br />

Honorary Chairmen<br />

Thomas L. Farmer<br />

Henry A. Kissinger<br />

Richard von Weizsäcker<br />

Chairman<br />

Richard C. Holbrooke<br />

Vice Chairman<br />

Gahl Hodges Burt<br />

President<br />

Robert H. Mundheim<br />

Treasurer<br />

Karl M. von der Heyden<br />

Trustees<br />

Gahl Hodges Burt<br />

Gerhard Casper<br />

Lloyd Cutler<br />

Jonathan F. Fanton<br />

Thomas L. Farmer<br />

Julie Finley<br />

Vartan Gregorian<br />

Jon Vanden Heuvel<br />

Karl M. von der Heyden<br />

Richard C. Holbrooke<br />

Dieter von Holtzbrinck<br />

Dietrich Hoppenstedt<br />

Josef Joffe<br />

Stephen M. Kellen<br />

Henry A. Kissinger<br />

Horst Köhler<br />

John C. Kornblum<br />

Otto Graf Lambsdorff<br />

Nina von Maltzahn<br />

Deryck Maughan<br />

Klaus Mangold<br />

Erich Marx<br />

Wolfgang Mayrhuber<br />

Robert H. Mundheim<br />

Joseph Neubauer<br />

Franz Xaver Ohnesorg<br />

Robert Pozen<br />

Volker Schlöndorff<br />

Fritz Stern<br />

Kurt Viermetz<br />

Alberto W. Vilar<br />

Richard von Weizsäcker<br />

Klaus Wowereit, ex officio

12m<br />

multiplying knowledge.<br />

We at Schering know that knowledge creates value. As an expanding pharmaceutical and biotechnology company, we cooperate<br />

with top specialists to create a pool of knowledge to further medical progress. Based on causal research we develop products<br />

of high clinical value and tailored treatments to enhance and sustain the quality of human life. We know our longterm<br />

success depends on reaching this goal. Schering – making medicine work.<br />

www.schering.de<br />

The Berlin Prize Fellowships 2004 – 2005<br />

The American Academy in Berlin invites applications for its fellowships for<br />

the 2004–2005 academic year. The Academy is a private, non-profit center<br />

for the advanced study of culture and the arts, music, law, public policy,<br />

finance and economics, historical, and literary research. It welcomes<br />

younger as well as established scholars, artists, and professionals who wish<br />

to engage in independent study in Berlin for an academic semester or in<br />

special cases for an entire academic year.<br />

The Academy, which opened its doors in September 1998, occupies the<br />

Hans Arnhold Center, a historic lakeside villa in the Wannsee district of<br />

Berlin. Fellowships have been awarded to writers and poets, painters and<br />

sculptors, curators, anthropologists, German cultural scholars, economists,<br />

historians, theologians, legal scholars, journalists, architectural and<br />

cultural critics, composers and musicologists and public policy experts.<br />

Specially designated fellowships include the Bosch Fellowship in Public<br />

Policy, the George Herbert Walker Bush Fellowship, the Citigroup<br />

Fellowship, the DaimlerChrysler Fellowship, the Gillette Fellowship, the<br />

Ellen Maria Gorrissen Fellowship, the Haniel Foundation Fellowship, the<br />

Holtzbrinck Fellowship in Journalism, the Anna-Maria Kellen Fellowship,<br />

the JP Morgan International Prize in Finance Policy and Economics, and the<br />

Guna S. Mundheim Fellowship in the Visual Arts.<br />

US citizens and permanent residents (in both cases permanently based in<br />

the United States) are eligible to apply. Fellows are expected to be in residence<br />

at the Academy during the entire term of their awarded semester.<br />

The Academy offers furnished apartments suitable for individuals and<br />

couples, and a very limited number of accommodations for families with<br />

children. Benefits include a monthly stipend, round-trip airfare, housing at<br />

the Academy and partial board. Stipends range from $3000 to $5000 per<br />

month (depending on level of attainment).<br />

Application forms are available from the Academy or may be downloaded<br />

from its web site (www.americanacademy.de). Applications for all fellowships<br />

(with the exception of applications in the visual arts and music, due in<br />

New York by December 1, <strong>2003</strong>) must be received in Berlin by October 31,<br />

<strong>2003</strong>. Candidates need not be German specialists, but the project description<br />

should explain how a residency in Berlin will contribute to further<br />

professional development.<br />

Applications will be reviewed by an independent selection committee<br />

following a peer review process. The 2004–2005 Fellows will be chosen in<br />

January 2004 and publicly announced in early spring.<br />

American Academy in Berlin<br />

Am Sandwerder 17-19<br />

D-14109 Berlin, Germany<br />

Telephone +49 (30) 804 83 - 0<br />

Fax +49 (30) 804 83 - 111<br />

applications@americanacademy.de<br />

T HE<br />

A M E R IC A N<br />

AC ADE M Y<br />

I N B E R LIN<br />

HansArnholdCenter

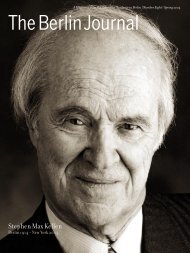

Robert H. Mundheim Introduces Paul Volcker<br />

On October 7, 2002, Academy president Robert H.<br />

Mundheim welcomed an audience to the Hans Arnold<br />

Center for the inaugural Stephen Kellen Lecture.<br />

The lecture series was announced last spring on the<br />

occasion of the founding trustee’s eighty-eighth birthday.<br />

Mundheim made the following remarks to honor<br />

the man after whom the lecture is named and to introduce<br />

the very first Kellen lecturer, Paul Volcker.<br />

Stephen Kellen is both a Berliner and an American. It<br />

has been his dream to draw together the city of his birth<br />

and his adopted country, and he has done that in a variety<br />

of ways: by bringing the Berlin Symphony Orchestra<br />

to Carnegie Hall, by sponsoring Germans to study in the<br />

United States, and by being a prime supporter, in every<br />

way, of the American Academy in Berlin, housed in the<br />

former home of his wife, Anna-Maria Arnhold Kellen.<br />

The American Academy functions, basically, as a<br />

private cultural embassy to Berlin and to Germany.<br />

The dozen or so Berlin Prize Fellows who live here each<br />

semester are its principal ambassadors. They embody<br />

the richness and diversity of American culture and<br />

values. The Academy is also a forum for exchanging<br />

ideas, linking people, and promoting understanding.<br />

This role is of special significance at a time when official<br />

relations between our two governments seem to be<br />

under some strain. I have never been more convinced of<br />

the importance to Germans and Americans of the<br />

American Academy, which Richard Holbrooke, Richard<br />

von Weizsäcker, Henry Kissinger, Gary Smith, and above<br />

all, Stephen Kellen, have built. The creation of the<br />

Stephen Kellen Lectures represents a “thank you” to<br />

Stephen from the Academy trustees, who contributed<br />

individually to fund them.<br />

The first Kellen Lecture is given by Paul Volcker, a man<br />

whom Stephen admires enormously. Stephen was<br />

pleased with his theme – “Protecting the Integrity of the<br />

Markets” – because he has been a lifelong investment<br />

banker and has adhered to a set of values that protected<br />

market integrity. He has watched, I think, with some dismay,<br />

as those values have eroded. The topic also marks<br />

a fitting occasion to launch the American Academy’s<br />

new series of JPMorgan Economic Policy Briefs, with<br />

the generous help of JPMorgan Chase.<br />

Economist Paul Volcker’s forebears were German, from<br />

Westphalia. From Princeton and Harvard, he went on to<br />

a distinguished career in public service. I will mention<br />

some highlights. He served as Undersecretary for<br />

Monetary Affairs in the Nixon Treasury at a time when<br />

the undersecretary had international and domestic<br />

finance, as well as economic policy, within his jurisdiction.<br />

Later, he became the president of the New York<br />

Federal Reserve Bank – probably the most powerful of<br />

the 12 Federal Reserve Bank districts. One may remember<br />

that the US experienced financial trouble in the late<br />

1970s. Interest rates reached double digits. Inflation was<br />

high; the cost of living increased by 40 percent in<br />

roughly three years. The dollar was weak. The US had to<br />

borrow money in Germany and in Switzerland, the Carter<br />

Notes. The then-chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank,<br />

Bill Miller, had just been appointed Secretary of the<br />

Treasury. The president said, ‘we need someone who can<br />

see into the future clearly and devise solutions to get us<br />

out of the mess we’re in.’ And his advisors responded,<br />

‘we know a perfect candidate! He’s 6-foot 7-inches tall.<br />

Surely he can see into the future better than anyone<br />

else.’ Well, I don’t know if they were right about the<br />

advantages of height, but I do know that Paul Volcker<br />

did help us get out of the financial mess we were in.<br />

His leadership of the Federal Reserve Bank has been<br />

universally admired.<br />

Paul Volcker’s post-government service includes<br />

teaching at Princeton and New York University.<br />

He has chaired the committee dealing with Holocaust<br />

claims against Swiss financial institutions. He has<br />

authored two reports on the reform of the US Government,<br />

the last of which was submitted in January of<br />

<strong>2003</strong>. He chairs the International Accounting Standards<br />

Committee Foundation. Even this abbreviated list<br />

indicates that Paul Volcker’s life is rich with experience.<br />

We are delighted that he shares some of that<br />

experience with the American Academy in Berlin. uu<br />

Protecting the<br />

Integrity of<br />

Capital Markets<br />

A New Priority<br />

--------------------<br />

Paul A. Volcker<br />

Photograph: Lawrence Chaperon

The present challenge in German-American<br />

relations has brought me to reflect on my own<br />

years in government.<br />

I was privileged to work with a long line of distinguished<br />

German central bankers and finance and<br />

economy ministers. Those relationships extending<br />

over thirty years tell their own story. They were<br />

stronger than with any other country. The<br />

US and Germany, with the largest and strongest<br />

economies, have been anchors of the transatlantic<br />

alliance, an alliance that has served the world well.<br />

Perhaps that relationship has been diluted a bit, but<br />

it would be a tragedy for it to break down. I know<br />

the American Academy in Berlin has become one<br />

of the institutions designed to make sure that does<br />

not happen.<br />

Neither that history nor this institution fully<br />

explain why I take such satisfaction in presenting<br />

this lecture. Stephen and Anna-Maria Kellen are a<br />

remarkable couple. I know them as major contributors<br />

to the cultural life of New York City. But all else<br />

pales beside their personal commitment – a commitment<br />

rising above events that could well have<br />

embittered lesser men or women – to strengthening<br />

ties between their native and adopted countries.<br />

The American Academy in Berlin is one reflection of<br />

that commitment, and it is an honor to give the first<br />

Stephen Kellen Lecture. Appropriately, the series<br />

has been established in recognition both of<br />

Stephen’s professional life in financial affairs and<br />

his dedication to the interests of his two countries.<br />

It is fitting, but also a bit ironic, that my theme<br />

is the need to restore the integrity of capital markets,<br />

not least in the US. That is a subject upon<br />

which we Americans have been fond of lecturing<br />

others, and certainly Stephen Kellen and the firm<br />

of Arnhold and S. Bleichroeder, Inc. have represented<br />

the best of our traditions. We cannot, however,<br />

escape the fact that the truly historic boom in<br />

the American stock market in the 1990s has been<br />

accompanied by weaknesses in our corporate culture.<br />

Ethical breakdowns among financial market<br />

participants are widely recognized. The procession<br />

of flagrant examples – beginning even before the<br />

sensational collapses of Enron and the Arthur<br />

Andersen accounting firm – has preoccupied business<br />

reporting for months at a time.<br />

I do not believe that the apparent fraud or<br />

corporate looting of Enron, WorldCom, Global<br />

Crossing, Adelphia, Tyco, and others are at all representative<br />

of American business practices. But I do<br />

fear they are an extreme manifestation of a more<br />

widespread tendency to “push the envelope” of<br />

what is acceptable in business practice.<br />

It is not accidental that these developments<br />

took place in the midst of a virtually unprecedented<br />

stock market bubble and subsequent decline. Quite<br />

suddenly in the 1990s unimagined fortunes could<br />

be made on Wall Street. There seemed to be a sense<br />

of the entitlement of wealth. Alan Greenspan<br />

caught the spirit in his phrase “infectious greed.”<br />

A reflection of this has been executive compensation,<br />

which has far exceeded earlier norms in relation<br />

to average pay. Somehow, such excesses did not<br />

seem shocking when the escalating stock market<br />

exceeded all expectations. But now, to drive the lesson<br />

home, are examples of payments of tens of millions<br />

of dollars (at times more than one hundred<br />

million dollars) to executives of failing companies<br />

and huge separation arrangements to ethically tarnished<br />

officials in the midst of falling markets.<br />

A whole new profession of financial<br />

engineering has been invented,<br />

-------------------------------<br />

with its richly rewarded practice<br />

directed toward finding ways around<br />

accounting standards and tax<br />

regulations.<br />

-------------------------------<br />

Much of the anger has been directed at Andersen<br />

and other auditing firms for failing to detect and<br />

report the abuses in financial reporting. But the<br />

responsibility should be spread more widely.<br />

The large investment banks and the big commercial<br />

banks, in aggressively diversifying into<br />

lending, trading, stock research, and investment<br />

company conglomerates, have become nests of<br />

conflict. A whole new profession of financial engineering<br />

has been invented, with its richly rewarded<br />

practice directed in large part toward finding ways<br />

around accounting standards and tax regulations.<br />

Consultants and advisors are readily available<br />

to promote and justify ever-bigger mergers and<br />

acquisitions and to rationalize a ratcheting up of<br />

executive pay.<br />

One disillusioned Wall Streeter went even<br />

further when he commented to me, “What can you<br />

expect? For decades our best business schools have<br />

preached the doctrine that whatever boosts the<br />

stock price is ‘value added.’ ”<br />

These troubles have relevance far beyond the<br />

US. The organizations involved are typically international.<br />

No doubt Europeans will be familiar with<br />

the parallels in Europe. What may be more important<br />

– and overlooked – is the potential impact on opinion<br />

in the emerging and transitional economies. If there<br />

are strong doubts about the integrity of our capital<br />

markets, those who question the acceptability of<br />

global financial markets will have their doubts reinforced.<br />

One need only recall the emphasis, after the<br />

Asian financial crisis, placed by the International<br />

Monetary Fund, the World Bank, our governments,<br />

and private financial institutions alike on the weakness<br />

of indigenous financial practices as a precipitating<br />

and complicating factor. ‘If only,’ so the refrain<br />

went, ‘the emerging countries had US-style accounting<br />

standards, disciplined auditing, and transparency<br />

– if only they had stronger legal and ethical traditions<br />

and less crony capitalism – then they would not have<br />

been so vulnerable.’<br />

That message was woefully incomplete. Other<br />

more structural and systemic factors were at work.<br />

The openness and the small size of the financial sectors<br />

of emerging economies made and still make<br />

them especially vulnerable to the inevitable volatility<br />

of free financial markets. Nonetheless, those countries<br />

cannot find “salvation” – cannot reach anything<br />

like their potential growth – without participating in<br />

global markets and, particularly, without continuous<br />

inflow of direct investment. If we cannot make good<br />

on our implicit boast that our capitalist financial<br />

institutions are honestly and ethically governed –<br />

that our business and financial reporting standards<br />

are worthy of emulation – then the willingness to<br />

accept foreign investment and the process of economic<br />

development will be dealt a serious blow.<br />

Of course, it is specifically our gaap (Generally<br />

Accepted Accounting Practices), our auditing firms,<br />

our sec (Securities and Exchange Commission), and<br />

our legal system that have been seen as constituting<br />

the model. Given the American weight in the world<br />

economy and the economically strong and technologically<br />

cutting-edge performance of the US in the<br />

1990s, that perception is perhaps natural, whatever<br />

its intrinsic merit.<br />

We in the US must bring our practice more closely<br />

into line with what we preach. It is important in our<br />

own interest. It is important to Germany and other<br />

already industrialized countries that have a big stake<br />

in the success of a globalized financial system. And it<br />

may well be crucial to those countries that aspire to<br />

our economic success but face entrenched interests<br />

that resist change, modernization, and full participation<br />

in the world economy.<br />

The good news is that we have had a “wake-up<br />

call.” The loss of some eight trillion dollars in stock<br />

market valuations over the past three years has<br />

attracted attention. The examples of gross corporate<br />

malfeasance have provided political impetus for<br />

change.<br />

4 Number Six | <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2003</strong>

The bad news is that constructive change will<br />

not be easy. There can be no turning back the technological<br />

changes that have spawned the mindbending<br />

complexity of today’s financial markets.<br />

Our established accounting and financial reporting<br />

models were designed for a world of relatively simple<br />

manufacturing and service companies – not for<br />

the “virtual” world of derivatives, options, securitization,<br />

massive intangibles, and trading-dominated<br />

balance sheets and income statements.<br />

Accounting and auditing have, for good reason,<br />

been thrust to the front and center of the reform<br />

effort. An auditor’s ultimate responsibility is not to<br />

the corporate clients, but to the investor, to the market,<br />

and, finally, to the general public. Public corporations<br />

in the US have no choice but to follow US<br />

gaap and to have their accounts audited by a<br />

certified professional. This is also true for any company<br />

that wants to raise capital in the US and that<br />

have its securities freely traded there. Increasingly,<br />

similar requirements are in place in other countries<br />

as well.<br />

The first requirement is a creditable accounting<br />

model, with comprehensive, up-to-date and<br />

enforceable standards. Further, the logic of globalized<br />

finance requires a set of internationally<br />

agreed and accepted accounting standards. The<br />

existing system in the US meets neither criterion.<br />

The perceived crisis in accounting triggered by<br />

recent events has surely punctured the sense of<br />

sanctity that had surrounded American gaap.<br />

Now, there are pressures for a simpler, more<br />

straightforward, statement of principles better<br />

adapted to today’s world. Recognition of the need<br />

for change, for standardization across countries,<br />

and for insulation from national political pressures<br />

has enhanced the prospects of converging on an<br />

international standard.<br />

Those objectives cannot be reached quickly,<br />

however. The intellectual, organizational, and political<br />

obstacles are substantial. But what seemed<br />

unrealistic and impossibly visionary a few years ago<br />

now seems both possible and necessary.<br />

The consistent application of international<br />

accounting principles will depend upon the discipline<br />

and the professionalism of auditors. It is now<br />

apparent that the big American accounting firms<br />

have fallen short, bending too readily to the strong<br />

pressures from clients and an intensely competitive<br />

marketplace. My experience working with<br />

Andersen, though brief, was long enough to confirm<br />

the impression that the firm was distracted and<br />

conflicted by the unceasing emphasis on more<br />

remunerative consulting services. Those circumstances<br />

are not unique to one firm.<br />

Executive compensation is another area in need<br />

of reform. There is little doubt in the US that the<br />

spreading practice of providing stock options has<br />

been the prime instrument driving the process.<br />

Typically, those options take the form of a one-way<br />

option to purchase stock at the price prevailing on<br />

the day of grant, vesting a few years in the future.<br />

Prevailing practice, as the result of political pressure,<br />

has been to exclude that form of compensation<br />

as a business expense on income statements, which<br />

increases its attractiveness to management.<br />

(Inconsistently, the difference between the option<br />

price and the higher market price at the time it is<br />

exercised is recognized as an expense for tax<br />

purposes.)<br />

The combination of generous options and<br />

booming stock prices has produced large – at times<br />

incomprehensibly large – rewards to top executives.<br />

An instrument widely touted as aligning the interests<br />

of management with stockholders is now widely<br />

perceived as capricious in practice. In a bull market,<br />

with the valuations of stocks rising across the board,<br />

not only the best, but also the mediocre and even<br />

sub-par performers are rewarded. Conversely, when<br />

the stock market moves lower for several years, even<br />

the most (relatively) successful managers may benefit<br />

little or not at all, bringing pressure to reprice<br />

existing options or provide successively more<br />

options at lower prices. To compound the problem,<br />

incentives for managers can be perverse, reinforcing<br />

a focus on short-term results and manipulation of<br />

financial reports.<br />

Finally, broader questions of corporate governance<br />

are being forcibly raised. A feature of the<br />

American model has been the unique power of the<br />

chief executive officer. In theory, a company’s board<br />

of directors represents the owners and exercises<br />

oversight and direction over its agent, the ceo and<br />

management. In practice, the American ceo is also<br />

typically chairman of the board and has heavy<br />

influence over the choice of board members. The<br />

arrangement has been almost sacrosanct in the view<br />

of most ceos, who hold that their authority must<br />

not be diluted and that it protects their ability to<br />

promote innovation and take risks. As many know,<br />

this is not the standard governing pattern in most<br />

other industrialized countries.<br />

Matters of corporate governance, in particular<br />

the organization and modus operandi of boards of<br />

directors, have for some time made up a cottage<br />

industry for American consultants. But only now,<br />

The good news is that we have had<br />

a “wake-up call” – the loss of some<br />

eight trillion dollars in stock market<br />

valuations over the past three years.<br />

--------------------------------<br />

The bad news is that constructive<br />

change will not be easy.<br />

--------------------------------<br />

with the pressure of recent events, has this discussion<br />

come to take on the basic issues: effective oversight<br />

of the ceo, compensation practices, and<br />

financial reporting.<br />

The forces against effective reform in these and<br />

other areas remain strong. Vested interests and vast<br />

sums of money add to the confusion. Arguments<br />

have been pressed regarding the danger of political<br />

and legislative responses, that such responses could<br />

stifle the innovation and risk-taking at the heart of<br />

American economic success. And indeed, we have<br />

had experience with the unintended consequences<br />

of legislation passed in haste. There are such<br />

dangers, but there is also a role for legislation today,<br />

just as there was a role for it in the 1930s after the<br />

excesses of the 1920s.<br />

The best defense against political and legislative<br />

“overkill” is effective reform within the corporate<br />

community itself. In particular, effort is necessary in<br />

the three critical areas of financial reporting, compensation,<br />

and corporate governance.<br />

I chair the International Accounting Standard<br />

Committee Foundation, an organization that<br />

embodies the effort to seek convergence of accounting<br />

standards globally. Our committee’s particular<br />

responsibility is to appoint the board of professionals<br />

– the iasb – charged with developing standards<br />

of broad applicability and high quality.<br />

Our efforts are not entirely free of political pressures<br />

or special industry pleading – these are endemic<br />

– but the inherently international composition<br />

of the committee and the board that it appoints<br />

helps neutralize and diffuse those pressures. Europe<br />

and much of the rest of the world, by legislation or<br />

otherwise, has signaled its willingness to adopt international<br />

standards. My sense is that the insularity of<br />

the American view is fading, and the US authorities<br />

are now willing and eager to find common ground.<br />

The spotlight is now on the capacity of accounting<br />

professionals around the world to arrive at a<br />

strong consensus on new principles and rules that<br />

are well adapted to the complexities of the twentyfirst<br />

century. We will insist that the iasb decisionmakers<br />

consult broadly and follow due process. It is<br />

not an easy task, but the need is urgent.<br />

Good standards are not enough. They must be<br />

applied with consistency and discipline. This is an<br />

The Berlin Journal 5

area in which legislation has been clearly needed,<br />

and now has been achieved. The newly enacted<br />

Sarbanes-Oxley Act will reduce the conflicts and distractions<br />

caused by the past emphasis of accounting<br />

firms on their consulting practices. It also provides<br />

for effective oversight of auditing practices by a<br />

body removed from industry control.<br />

The fact that earlier industry-sponsored and -<br />

controlled oversight efforts failed makes a dramatic<br />

case for arrangements that are more analogous to<br />

those long in force in the US securities industry.<br />

What remains is to provide for effective administration.<br />

The appointment of a strong oversight<br />

board is key, but there needs to be cultural change<br />

within auditing firms themselves.<br />

Success will depend, too, upon a new sense of<br />

discipline in the corporate boardroom. For one<br />

thing, a more effective, more disciplined auditing<br />

process entails cost. That applies especially to the<br />

compensation of the outside auditors. Too many<br />

corporations have looked upon auditing fees as a<br />

cost, to be squeezed to the extent practical, especially<br />

when the possibility of profitable consulting<br />

assignments is available to the accounting firm.<br />

Today, boards of directors, ceos, and chief financial<br />

officers are more alert to the need to assure accurate<br />

financial reporting. But will these attitudes persist<br />

after the present crisis passes?<br />

A heavy weight is being placed on audit committees.<br />

They will require more time, more financial<br />

sophistication, and more authority. Members of<br />

boards of directors are chosen – quite rightly – to<br />

achieve a variety of perspectives and to bring different<br />

strengths to the board. They typically develop a<br />

collegial relationship with management. The question,<br />

however, is how boards as presently constituted<br />

can find members with the capacity, the time,<br />

and the will to oversee the auditing and accounting<br />

of a large and financially complicated corporation<br />

effectively. This is especially difficult when a high<br />

value is (understandably) placed upon the collegiality<br />

of a board, whose main responsibility remains<br />

to advise the company and consult on strategic<br />

matters and vital personnel decisions.<br />

One way around the conundrum could be to<br />

rethink the way auditing committees are selected.<br />

Why not ask stockholders themselves to select<br />

members of the auditing committee, electing them<br />

either as a separate committee reporting to the<br />

board of directors or simply as an identifiable part<br />

of the board itself? Such an arrangement could provide<br />

better focus for the heavy responsibilities of<br />

audit committees, and in doing so, better match the<br />

responsibilities with those able to discharge them.<br />

In the US, the responsibilities of the auditing<br />

committee are essentially spelled out in the new<br />

Sarbanes-Oxley Act and in most of the writings on<br />

corporate governance. They include hiring the auditor,<br />

deciding on an appropriate fee, exercising oversight<br />

over both the external and internal auditing<br />

processes, and assessing corporate controls. For a<br />

large and complicated public company, these are<br />

substantial responsibilities, requiring both relevant<br />

experience and a lot of time. For most boards, such<br />

resources are scarce.<br />

In a broader context, I am encouraged by the<br />

fact that discussion is underway about separating<br />

the responsibilities of the ceo and board chairman.<br />

Some variation of that approach is common in the<br />

United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries<br />

and on the European continent as well. In<br />

Germany, the chairman of the supervisory board<br />

seems to have a comparable oversight role.<br />

The “imperial ceo” is strongly entrenched in<br />

the US, however. Few incumbent or aspiring ceos<br />

would want to contemplate giving up any authority<br />

with respect to setting the board agenda and managing<br />

board discussions. But recent events have<br />

illustrated the dilemma. There is broad agreement<br />

that, for the stockholder’s sake, ultimate control of<br />

the corporation should lie with directors independent<br />

of management. If so, should there not be a clear<br />

focus for board leadership beyond the ceo? Who<br />

can act when there are doubts about the ceo himself?<br />

Who should take the initiative among the independent<br />

directors? Are those matters better left to a<br />

more spontaneous and informal response to perceived<br />

crisis or to a part of established board procedures?<br />

I do not suggest that one size should fit all. But I<br />

do believe that for large and complicated public<br />

companies, the check and balance implicit in a nonexecutive<br />

chairman should be the norm. For one<br />

thing, independent board leadership would help<br />

maintain more effective control over executive<br />

remuneration – remuneration that, as is now recognized,<br />

has in some cases been grotesquely large and<br />

inconsistent with performance. It is also important<br />

to understand that the widely disproportionate<br />

growth in executive compensation is a function of<br />

the widespread use of fixed-price stock options<br />

interacting with a bull market for stocks that<br />

exceeded all expectations. The capricious results of<br />

those perverse incentives came from a failure to<br />

align the long-term interests of stockholders with<br />

management.<br />

Of course stock options may well be useful for<br />

small, risky, and cash-starved ventures without<br />

access to public markets. For established public companies,<br />

options closely related to relative performance<br />

over extended periods may be designed. But for<br />

broadly owned public companies with active markets<br />

for their stock, there should be strong presumption<br />

against the practice of fixed-price options for<br />

executives. The temptation for abuse is simply too<br />

great and will remain so even if, contrary to present<br />

practice, they are “expensed.” If equity ownership by<br />

executives is desirable – and I believe it is – there are<br />

more effective ways to achieve that end, including<br />

grants of stock with restrictions on sale.<br />

A global economy with the free flow of capital<br />

has the potential of bringing enormous benefits to<br />

the emerging as well as the economically developed<br />

world. But, as many know, there is resentment and<br />

resistance. Much of this opposition may rest on false<br />

and specious grounds, but it is also true that much<br />

more needs to be done before many emerging<br />

economies reach their potential. Rhetoric that trumpets<br />

the benefits of international financial markets<br />

will ring hollow so long as the integrity of the capital<br />

markets of the developed world is challenged.<br />

The weaknesses in corporate governance and in<br />

accounting and financial reporting in the US have<br />

been exposed for all to see, and the challenge is not<br />

limited to my own country. It is a matter of multinational<br />

companies, accounting firms that operate<br />

globally, and international markets.<br />

What is happening today in the US offers a certain<br />

degree of comfort and satisfaction. We are acting<br />

with a reasonable mixture of private initiative<br />

and legislation to deal forcibly with problems that<br />

have been neglected for too long. There is still a long<br />

Rhetoric trumpeting the benefits of<br />

international financial markets will<br />

ring hollow so long as the integrity of<br />

the developed world’s capital markets<br />

is challenged.<br />

--------------------------------<br />

way to go to assure reforms are undertaken and<br />

maintained, and it is not, moreover, a challenge for<br />

one country alone, however large and influential it<br />

may be.<br />

I believe that the end result must bring our practice<br />

more closely into line with our stated principles.<br />

Taking critical steps now to assure the integrity of<br />

our own capital markets will help pave the way for<br />

the acceptance of democratic capitalism the world<br />

over. o<br />

6 Number Six | <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2003</strong>

America:<br />

The Ambivalent<br />

Empire?<br />

Four Views<br />

Last fall, the human rights scholar Michael Ignatieff arrived for a<br />

seminar at the Hans Arnhold Center with a working draft of his<br />

forthcoming book Empire Lite under his arm. Among other<br />

matters discussed that day, Ignatieff pointed out how President<br />

Bush’s administration has painstakingly avoided using the<br />

language of empire. He cited a speech from June 2002 in which<br />

the president declared, “America has no empire to extend or<br />

utopia to establish.”<br />

American foreign policy has a long tradition of being ambivalent<br />

about empire. Sometimes the nation has been adamantly<br />

isolationist, other times, extroverted in its involvement abroad.<br />

The reluctance to serve as the world’s sheriff has often been at<br />

odds with both the Wilsonian image of America “making the<br />

world safe for democracy” and the more hard-headed pursuit of<br />

national interests.<br />

How circumspect is the US in its exercise of power? How will it<br />

choose to perpetuate its preeminence in the post-cold-war<br />

world? What are the pitfalls and promises of the American<br />

Empire? We asked four friends of the American Academy to<br />

comment: Ignatieff himself; Josef Joffe, one of our founding<br />

trustees; David Rieff, the spring Haniel Fellow; and Hans-Ulrich<br />

Wehler, a noted German historian.<br />

Michael Ignatieff Empire Lite<br />

Josef Joffe Lonely at the Top<br />

David Rieff An American Empire<br />

Hans-Ulrich Wehler The Chosen Nation<br />

8 Number Six | <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2003</strong>

Michael Ignatieff Empire Lite<br />

Reconciling Democracy and Empire<br />

It is unsurprising that force projection overseas should awaken<br />

resentment among America’s enemies. More troubling is the hostility<br />

it arouses among friends, those whose security is guaranteed by<br />

American power. Nowhere is this more obvious than in Europe. At a<br />

moment when the costs of empire are mounting for America, her rich<br />

European allies matter financially. But in America’s emerging global<br />

strategy, they have been demoted to reluctant junior partners. This<br />

makes them resentful and unwilling allies, less and less able to understand<br />

the nation that liberated them in 1945.<br />

For fifty years, Europe rebuilt itself economically while passing on<br />

the costs of its defense to the United States. This was a matter of more<br />

than just reducing its armed forces and the proportion of national income<br />

spent on the military. All Western European countries reduced the martial<br />

elements in their national identities. In the process, European identity<br />

(with the possible exception of Britain) became postmilitary and postnational.<br />

This opened a widening gap with the US. It remained a nation in<br />

September 11 rubbed in the<br />

lesson that global power is still<br />

measured by military capability.<br />

which flag, sacrifice, and martial honor are central to national identity.<br />

Europeans who had once invented the idea of the martial nation-state<br />

now looked at American patriotism, the last example of the form, and no<br />

longer recognized it as anything but flag-waving extremism. The world’s<br />

only empire was isolated, not just because it was the biggest power but<br />

also because it was the West’s last military nation-state.<br />

September 11 rubbed in the lesson that global power is still measured<br />

by military capability. The Europeans discovered that they lacked<br />

the military instruments to be taken seriously and that their erstwhile<br />

defenders, the Americans, regarded them, in a moment of crisis, with suspicious<br />

contempt.<br />

Yet the Americans cannot afford to create a global order all on their<br />

own. European participation in peacekeeping, nation-building, and<br />

humanitarian reconstruction is so important that the Americans are<br />

required, even when they are unwilling to do so, to include Europeans in<br />

the governance of their evolving imperial project. The Americans essentially<br />

dictate Europe’s place in this new grand design. The US is multilateral<br />

when it wants to be, unilateral when it must be; and it enforces a new<br />

division of labor in which America does the fighting, the French, British,<br />

and Germans do the police patrols in the border zones and the Dutch,<br />

Swiss, and Scandinavians provide the humanitarian aid.<br />

This is a very different picture of the world than the one entertained<br />

by liberal international lawyers and human rights activists who<br />

had hoped to see American power integrated into a transnational legal<br />

and economic order organized around the United Nations, the World<br />

Trade Organization, the International Criminal Court and other international<br />

human rights and environmental institutions and mechanisms.<br />

Successive American administrations have signed on to those pieces of<br />

the transnational legal order that suit their purposes (the World Trade<br />

Organization, for example) while ignoring or even sabotaging those parts<br />

(the International Criminal Court or the Kyoto Protocol) that do not. A<br />

new international order is emerging, but it is designed to suit American<br />

imperial objectives. America’s allies want a multilateral order that will<br />

essentially constrain American power. But the empire will not be tied<br />

down like Gulliver with a thousand legal strings.<br />

On the new imperial frontier, in places like Afghanistan, Bosnia<br />

and Kosovo, American military power, together with European money<br />

and humanitarian motives, is producing a form of imperial rule for a<br />

postimperial age. If this sounds contradictory, it is because the impulses<br />

that have gone into this new exercise of power are contradictory. On the<br />

one hand, the semiofficial ideology of the Western world – human rights<br />

– sustains the principle of self-determination, the right of each people to<br />

rule themselves free of outside interference. This was the ethical principle<br />

that inspired the decolonization of Asia and Africa after World War II.<br />

Now we are living through the collapse of many of these former colonial<br />

states. Into the resulting vacuum of chaos and massacre a new imperialism<br />

has reluctantly stepped – reluctantly because these places are dangerous<br />

and because they seemed, at least until September 11, to be marginal<br />

to the interests of the powers concerned. But, gradually, this reluctance<br />

has been replaced by an understanding of why order needs to be brought<br />

to these places.<br />

Nowhere, after all, could have been more distant than Afghanistan,<br />

yet that remote and desperate place was where the attacks of September<br />

11 were prepared. Terror has collapsed distance, and with this collapse<br />

has come a sharpened American focus on the necessity of bringing order<br />

to the frontier zones. Bringing order is the paradigmatic imperial task,<br />

but it is essential, for reasons of both economy and principle, to do so<br />

without denying local peoples their rights to some degree of self-determination.<br />

Kosovo, Bosnia, Afghanistan –<br />

This is imperialism in a hurry: spend<br />

money, get results, turn the place back<br />

to the locals and get out.<br />

The old European imperialism justified itself as a mission to civilize,<br />

to prepare tribes and so-called lesser breeds in the habits of self-discipline<br />

necessary for the exercise of self-rule. Self-rule did not necessarily<br />

have to happen soon – the imperial administrators hoped to enjoy the<br />

sunset as long as possible – but it was held out as a distant incentive, and<br />

the incentive was crucial in co-opting local elites and preventing them<br />

from passing into open rebellion. In the new imperialism, this promise of<br />

self-rule cannot be kept so distant, for local elites are all creations of modern<br />

nationalism, and modern nationalism’s primary ethical content is<br />

self-determination. In Iraq, local elites must be ‘‘empowered’’ to take over<br />

The Berlin Journal 9

as soon as the American imperial forces have restored order and the<br />

European humanitarians have rebuilt the roads, schools, and houses.<br />

Nation-building seeks to reconcile imperial power and local self-determination<br />

through the medium of an exit strategy. This is imperialism in a<br />

hurry: to spend money, to get results, to turn the place back to the locals<br />

and get out. But it is similar to the old imperialism in the sense that real<br />

power in these zones – Kosovo, Bosnia, Afghanistan and soon, perhaps,<br />

Iraq – will remain in Washington.<br />

At the beginning of the first volume of The Decline and Fall of the<br />

Roman Empire, published in 1776, Edward Gibbon remarked that<br />

empires endure only so long as their rulers take care not to overextend<br />

their borders. Augustus bequeathed his successors an empire ‘‘within<br />

those limits which nature seemed to have placed as its permanent bulwarks<br />

and boundaries: on the west the Atlantic Ocean; the Rhine and<br />

Danube on the north; the Euphrates on the east; and towards the south<br />

the sandy deserts of Arabia and Africa.’’ Beyond these boundaries lay the<br />

Empires survive when they understand<br />

that diplomacy, backed by force, is<br />

always to be preferred to force alone.<br />

barbarians. But the ‘‘vanity or ignorance’’ of the Romans, Gibbon went<br />

on, led them to ‘‘despise and sometimes to forget the outlying countries<br />

that had been left in the enjoyment of a barbarous independence.’’ As a<br />

result, the proud Romans were lulled into making the fatal mistake of<br />

‘‘confounding the Roman monarchy with the globe of the earth.’’<br />

This characteristic delusion of imperial power is to confuse global<br />

power with global domination. The Americans may have the former, but<br />

they do not have the latter. They cannot rebuild each failed state or<br />

appease each anti-American hatred, and the more they try, the more they<br />

expose themselves to the overreach that eventually undermined the classical<br />

empires of old.<br />

The secretary of defense may be right when he warns the North<br />

Koreans that America is capable of fighting on two fronts – in Korea and<br />

Iraq – simultaneously, but Americans at home cannot be overjoyed at<br />

such a prospect, and if two fronts are possible at once, a much larger<br />

number of fronts is not. If conflict in Iraq, North Korea, or both becomes<br />

a possibility, Al Qaeda can be counted on to seek to strike a busy and<br />

overextended empire in the back. What this suggests is not just that overwhelming<br />

power never confers the security it promises but also that even<br />

the overwhelmingly powerful need friends and allies. In the cold war, the<br />

road to the North Korean capital, Pyongyang, led through Moscow and<br />

Beijing. Now America needs its old cold-war adversaries more than ever<br />

to control the breakaway, bankrupt Communist rogue that is threatening<br />

America and her clients from Tokyo to Seoul.<br />

Empires survive when they understand that diplomacy, backed by<br />

force, is always to be preferred to force alone. Looking into the still more<br />

distant future, say a generation ahead, resurgent Russia and China will<br />

demand recognition both as world powers and as regional hegemons. As<br />

the North Korean case shows, America needs to share the policing of nonproliferation<br />

and other threats with these powers, and if it tries, as the<br />

current National Security Strategy suggests, to prevent the emergence of<br />

any competitor to American global dominance, it risks everything that<br />

Gibbon predicted: overextension followed by defeat.<br />

America will also remain vulnerable, despite its overwhelming military<br />

power, because its primary enemy, Iraq and North Korea notwithstanding,<br />

is not a state, susceptible to deterrence, influence and coercion,<br />

but a shadowy cell of fanatics who have proved that they cannot be<br />

deterred and coerced and who have hijacked a global ideology – Islam –<br />

that gives them a bottomless supply of recruits and allies in a war, a war<br />

not just against America but against her client regimes in the Islamic<br />

world. In many countries in that part of the world, America is caught in<br />

the middle of a civil war raging between incompetent and authoritarian<br />

regimes and the Islamic revolutionaries who want to return the Arab<br />

world to the time of the prophet. It is a civil war between the politics of<br />

pure reaction and the politics of the impossible, with America unfortunately<br />

aligned on the side of reaction. On September 11, the American<br />

empire discovered that in the Middle East its local pillars were literally<br />

built on sand.<br />

Until September 11, successive US administrations treated their<br />

Middle Eastern clients like gas stations. This was part of a larger pattern.<br />

After 1991 and the collapse of the Soviet empire, American presidents<br />

thought they could have imperial domination on the cheap, ruling the<br />

world without putting in place any new imperial architecture – new military<br />

alliances, new legal institutions, new international development<br />

organisms – for a postcolonial, post-Soviet world.<br />

The Greeks taught the Romans to call this failure hubris. It was<br />

also, in the 1990s, a general failure of the historical imagination, an<br />

inability of the post-cold-war West to grasp that the emerging crisis of<br />

state order in so many overlapping zones of the world – from Egypt to<br />

Afghanistan – would eventually become a security threat at home.<br />

Radical Islam would never have succeeded in winning adherents if the<br />

Muslim countries that won independence from the European empires<br />

had been able to convert dreams of self-determination into the reality of<br />

competent, rule-abiding states. America has inherited this crisis of selfdetermination<br />

from the empires of the past. Its solution – to create<br />

democracy in Iraq, then hopefully roll out the same happy experiment<br />

throughout the Middle East – is both noble and dangerous: noble<br />

because, if successful, it will finally give these peoples the self-determination<br />

they vainly fought for against the empires of the past; dangerous<br />

because, if it fails, there will be nobody left to blame but the Americans.<br />

The dual nemeses of empire in the twentieth century were nationalism,<br />

the desire of peoples to rule themselves free of alien domination,<br />

and narcissism, the incurable delusion of imperial rulers that the ‘‘lesser<br />

breeds’’ aspired only to be versions of themselves. Both nationalism and<br />

narcissism have threatened the American reassertion of global power<br />

since September 11. o<br />

© <strong>2003</strong> The New York Times Magazine.<br />

Michael Ignatieff is the Carr Professor and Director of the Carr<br />

Center for Human Rights Practice at the Kennedy School of Government,<br />

Harvard University. His next book is Empire Lite: Nation-building in<br />

Bosnia, Kosovo and Afghanistan is published this May in London. He presented<br />

a working version of this paper at the Academy last fall.<br />

10 Number Six | <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2003</strong>

Josef Joffe Lonely at the Top<br />

The Last Remaining Superpower<br />

Needs All the Help it Can Get<br />

Is america an empire? If so, it is a very strange kind of empire. It is<br />

not like Rome, a real imperium that started out with the small possession<br />

of Latium and then went on to conquer, occupy, and rule much<br />

of the then-known world – from the British Isles via Lusitania to the<br />

Levant. Nor is it like the Turkish or Russian empires, both of which relentlessly<br />

grabbed land to rule it – and to “russify” or “turkify” it.<br />

America is a very different kind of political animal. First of all, it<br />

was in the fortunate position of being able to conquer at home, so to<br />

speak. Its expansion was inward, into a largely unpopulated territorial<br />

expanse where it met with enemies (Native Americans, Mexicans) who<br />

were easily bested. There was also a natural limit to expansion: the<br />

Pacific, beyond which the young republic did not have to venture, since<br />

there were no existential threats on the other littoral. Similarly, the<br />

Atlantic provided a nice moat that kept dangerous European intruders at<br />

bay. Finally, there was a healthy revulsion against the “broils and troubles<br />

Alas, neither the French nor the<br />

Germans, neither the Chinese nor the<br />

Russians, show a proclivity to shoulder<br />

the burden and to pay the price.<br />

of Europe.” Better to stay out and not be contaminated by those corrupt<br />

princes and potentates who stood against all the values Americans cherished.<br />

And so it took some heavy prompting before the US intervened in<br />

Europe in 1917 and again in 1941.<br />

In short, the US did not conquer by dint of superior virtue but<br />

because it lacked those seemingly compelling reasons that relentlessly<br />

pushed Rome, Turkey, and Russia outward and forward. (Exceptions:<br />

Cuba and the Philippines in 1898, a misstep that might be excused by reference<br />

to the colonialist ideologies then in vogue.) Nor did the US have to<br />

conquer for economic reasons; again, it did very nicely by producing and<br />

exchanging goods in its vast home market. Indeed, until the 1970s,<br />

exports amounted to only four percent of its gdp, as opposed to export<br />

ratios of 30 percent in postwar West Germany or post-colonial Holland.<br />

Why then this overblown rhetoric of “empire” as attached to the<br />

United States? One explanation is that the US may well be the functional<br />

equivalent of empire. American bases and troops circle the globe, a fact<br />

made all the more remarkable given the demise of its one and only mortal<br />

rival, the Soviet Union. Its wars have become wars of choice, be it in<br />

Vietnam, in Afghanistan or in the Gulf. The US inserts its fleet between<br />

Taiwan and the Chinese mainland. Short of real war, it punishes<br />

malfeasants in places like Libya or pre-<strong>2003</strong> Iraq. And it waves the stick of<br />

war in the faces of countries like North Korea.<br />

A B<br />

Is this the behavior of a real empire? No, but it reflects a hegemonic<br />

mind-set not unlike Britain’s in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.<br />

America’s penchant is not for direct rule but for intermittent intervention<br />

in order to restore or uphold regional balances by laying low the local<br />

would-be hegemon du jour. Nor is this behavior necessarily a bad thing<br />

when analyzed in the language of cold realpolitik. This is a nasty world,<br />

with endless threats to regional stability and to the “decent opinions of<br />

mankind.” When local powers cannot take care of regional order, when<br />

fearsome despots like Milosevic or Saddam commit outrages against<br />

their own populations, there has to be somebody who upholds minimal<br />

standards of acceptable behavior.<br />

Alas, neither the French nor the Germans, neither the Chinese nor<br />

the Russians, show a proclivity to shoulder the burden and to pay the<br />

price. So, resorting once more to the cold language of power politics, one<br />

might breathe a sigh of relief and mutter: “Thank God for America.”<br />

Thank God for an “imperial republic,” as Raymond Aron called the US<br />

forty years ago, that does not conquer but intervenes, at least intermittently,<br />

to sober up those who challenge the status quo. In an ever more<br />

messy world, it would be easier to condemn the US if others were willing<br />

to discharge these tasks.<br />

The problem is overdoing it –<br />

and picking up more enemies in<br />

the process.<br />

So what are the problems? They have been well analyzed by<br />

Michael Ignatieff. The US may be a power even greater than Rome. It certainly<br />

dwarfs all possible comers. Just an example: When George W. Bush<br />

asked Congress for a supplemental defense appropriation in early 2002,<br />

the sum was more than twice that of Germany’s total annual defense<br />

budget. If the US goes on spending as planned, and if other countries do<br />

not increase their own efforts, it will invest more in its military panoply<br />

than all other nations combined.<br />

The Berlin Journal 11

The problem is not overspending, as “declinists” from Paul<br />

Kennedy onward have argued. Today, the US does not devote more<br />

resources to its military than did Germany during the Cold War: around 3<br />

percent of GDP. The problem is not even “overextension.” A geographical<br />

metaphor makes little sense in an age when American B-52s can rise in<br />

Missouri, fly halfway around the world, drop their ordnance on places<br />

like Afghanistan, and return home safely.<br />

The problem is overdoing it – and picking up more enemies, be<br />

they inspired by fear or hate, than are eliminated in the process of intrusion.<br />

Evidently, this intervention does not reduce the sum total of<br />

Cooperation may serve American<br />

interests better in the long haul than<br />

the most sophisticated military<br />

panoply.<br />

America’s ill-wishers. The problem is also underdoing the more economical<br />

or efficient thing, which is to harness friends and allies to the common<br />

purpose. Britain set the historical example; apart from the occasional<br />

naval engagement, it always fought coalition wars. This, of course,<br />

requires a surfeit of diplomatic skill (and patience) that may not be<br />

America’s strongest suit – at least not under the aegis of the Bush II<br />

administration.<br />

America’s problem is not decline but loneliness – and worse.<br />

“Worse” implies “ganging up” on the part of the lesser powers in the ways<br />

we have first seen this year. Two former allies of the US – France and<br />

Germany – have executed a kind of “reversal of alliances” by inducting<br />

their former enemy Russia into an anti-American “axis.” Now, it is true<br />

that the “hyperpower” can fend them off singly and in combination, but<br />

this is not the real issue. The point is that this “last remaining superpower”<br />

needs all the help it can get when it comes to the more interesting<br />

problems of the twenty-first century.<br />

We know the list. It ranges from terrorism to climate change, from<br />

proliferation to protectionism. Here is a very practical example: Even<br />

while Schröder was launching his rhetorical sallies against the Bush<br />

administration, American customs agents were peacefully collaborating<br />

with their German colleagues in the port of Hamburg. All of them were<br />

looking for terrorist contraband in containers bound for the US. These<br />

are the issues that directly and dangerously affect American welfare, and<br />

no power in the world can dispatch them on its own.<br />

One hopes that these “mundane” items of cooperation will occupy<br />

a larger space in the American diplomatic imagination once the Saddam<br />

problem is safely solved. Precision munitions are no substitute for cooperation.<br />

Indeed, in the long haul, the latter may serve American interests<br />

better than the most sophisticated military panoply. o<br />

Josef Joffe is editor and publisher of Die Zeit and an associate of the<br />

Olin Institute for Strategic Studies at Harvard University. He is a trustee<br />

of the American Academy in Berlin.

David Rieff An American Empire<br />

Imperialism, it seems, is back in vogue in America – at least<br />

among the chattering classes in Boston, New York, and Washington.<br />

Whether this enthusiasm of pundits and policy-wonks, by no means<br />

all of them on the right, will survive the actual experience of the practice<br />

of imperial policing, from Tora Bora to Bagdad, is another question. It is<br />

one thing to write about an “imperial renaissance‚” as the conservative<br />

British historian, Niall Ferguson, did at the end of his fine study of the<br />

British empire, and of the need to accept the fact that America’s global<br />

role demands that it take on the motley of empire. It is all very well to<br />

quote Kipling to the effect that the US military must accept its destiny of<br />

fighting “the savage wars of peace,” as the American writer Max Boot has<br />

done in his elegant neo-imperial polemics. But that is before the real savagery<br />

of war is brought home in video of maimed babies in bombed-out<br />

hospitals and funerals in south-central Los Angeles or the mountain hamlets<br />

of eastern Tennessee. However successful in military terms it has<br />

proven to be, the current punitive expedition in Iraq (for that, rather than<br />

a war in any normal sense is what it has been), so eerily reminiscent of the<br />

campaign of the fledgling US Marine Corps against the Barbary Pirates in<br />

the early nineteenth century, may well leave so sour a taste in the<br />

American public’s collective mouth that all fantasies of empire currently<br />

entertained in Washington will wilt like that city’s cherry blossoms when<br />

the summer heat sets in.<br />

But for the moment, however risible the idea may appear in the rest<br />

of the world, the idea that America is the planet’s only sure guarantor of<br />

liberty, and its corollary, that if there is to be a democratic revolution in the<br />

poor world on the same order of magnitude as the democratic revolution<br />

that extinguished the Soviet Union, or at least an avoidance of the worst<br />

horrors of imploding states like Rwanda and Bosnia that marked the<br />

first post-Cold War decade, only an America willing not just to be powerful<br />

but imperial will do, continues to dominate the policy debate in the<br />

United States. Open any of the neo-conservative magazines widely<br />

assumed to influence senior members of the Bush administration, and<br />

you will find a plethora of articles with gloating titles such as “Why<br />

America Must Police the World” and “What’s Wrong with an American<br />

Empire?” Meanwhile, on the liberal side, writers like Leon Wiesletier,<br />

Paul Berman, Samantha Power, and Michael Ignatieff, while duly skeptical<br />

of the Bush administration’s motives and conduct, are anything but<br />

hostile to a new Pax Americana. Ignatieff, in particular, has called for<br />

what he has dubbed “Empire Lite,” believing, not out of triumphalism<br />

but out of despair at the lack of any other solution that might stop a<br />

Rwandan genocide or bring to an end the almost uniquely evil tyranny of<br />

a Saddam Hussein (President Bush was two-thirds right when he evoked<br />