Summer 2001 | Issue 2

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

The Berlin Journal<br />

A NEWSLETTER FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY IN BERLIN • NUMBER TWO • SUMMER <strong>2001</strong><br />

IN THIS ISSUE<br />

Jenny Holzer<br />

on her Permanent<br />

Exhibition of Maxims<br />

in Berlin’s Neue<br />

Nationalgalerie<br />

plus:<br />

Gerald Feldman<br />

Richard Holbrooke<br />

Charles Maier<br />

Ward Just<br />

ATTILIO MARANZANO

The<br />

American<br />

Academy<br />

in Berlin<br />

Trustees of<br />

the American Academy<br />

Honorary Chairmen<br />

Thomas L. Farmer<br />

Henry A. Kissinger<br />

Richard von Weizsäcker<br />

Chairman<br />

Richard C. Holbrooke<br />

Vice Chairman<br />

Gahl Hodges Burt<br />

President<br />

Robert H. Mundheim<br />

Treasurer<br />

Karl M. von der Heyden<br />

Trustees<br />

Gahl Hodges Burt<br />

Gerhard Casper<br />

Lloyd Cutler<br />

Jonathan F. Fanton<br />

Thomas L. Farmer<br />

Julie Finley<br />

Vartan Gregorian<br />

Jon Vanden Heuvel<br />

Karl M. von der Heyden<br />

Richard C. Holbrooke<br />

Dieter von Holtzbrinck<br />

Dietrich Hoppenstedt<br />

Josef Joffe<br />

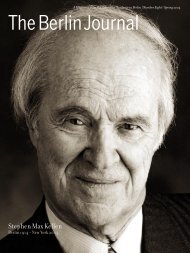

Stephen M. Kellen<br />

Henry Kissinger<br />

Horst Köhler<br />

John C. Kornblum<br />

Otto Graf Lambsdorff<br />

Nina von Maltzahn<br />

Klaus Mangold<br />

Erich Marx<br />

Robert H. Mundheim<br />

Robert Pozen<br />

Volker Schlöndorff<br />

Fritz Stern<br />

Kurt Viermetz<br />

Alberto W. Vilar<br />

Richard von Weizsäcker<br />

Klaus Wowereit<br />

The 20th Century is disappearing<br />

into History.<br />

But did it begin in 1900<br />

and span 100 years?<br />

Or did it start with WWI<br />

and end with the Fall of the<br />

Wall? Historian Charles Maier<br />

Letters of Hans Arnhold<br />

are a rare discovery made by<br />

Fellow Gerald Feldman. In<br />

January 1948, Hans Arnhold<br />

received a letter from a Weimar-period<br />

colleague – and<br />

fomer Nazi Reich Economics<br />

Jenny Holzer’s dramatic<br />

installation this spring at<br />

the Neue Nationalgalerie<br />

was such a success that it<br />

will return to the museum<br />

this fall as part of the permanent<br />

collection. Here,<br />

THE BERLIN JOURNAL<br />

A Record of Ideas<br />

and Visions<br />

As we launch the Hans Arnhold<br />

Center’s fourth exhilarating year,<br />

we continue to seek ways of making<br />

the Academy’s activities known to<br />

a largercommunityofcolleagues,<br />

media, benefactors, and interested<br />

members of the public. We’ve conceived<br />

The Berlin Journal to complement<br />

both our website www.americanacademy.de<br />

and the traditional<br />

fall publication of a Tagesspiegel<br />

supplement, showcasing the work<br />

of upcoming Berlin Prize Fellows.<br />

More substantial than a conventional<br />

institutional newsletter, our<br />

»newsletter as journal,« is a selective<br />

and subjective record of life and<br />

letters at the Academy. We will report<br />

on the accomplishments of our<br />

Richard Holbrooke<br />

Reflections on the vicissitudes of<br />

humanitarian intervention Page 10<br />

The Notebook<br />

of the American Academy Page 4<br />

Life and Letters<br />

at the Hans Arnhold Center Page 7<br />

In this <strong>Issue</strong><br />

fellows, the brilliant array of scholars,<br />

artists, and policy makers who<br />

visit us each year – from recent Berlin<br />

exhibitions of work by Jenny<br />

Holzer and Sarah Morris to the<br />

many scholarly colloquia and lectures<br />

by Academy scholars.<br />

Finally, each issue features substantial<br />

and original texts, many of<br />

them inspired by the eighty or so<br />

evenings of lectures, readings, and<br />

discussions that take place on the<br />

Wannsee each year. As a journal of<br />

ideas and information, we hope<br />

that The Berlin Journal provides an<br />

inspiring glimpse into the dynamism<br />

of our young institution and<br />

will motivate its readers to support<br />

its mission.<br />

argues that the modern<br />

worldis better demarcated<br />

by examining the years<br />

1860 to 1980, a period with<br />

more historical coherence<br />

than the notion of the<br />

»short century.« Page 12<br />

Minister – Kurt Schmitt. A<br />

remarkably frank and short<br />

correspondence followed.<br />

Gerald Feldman presents the<br />

fascinating exchange, places<br />

it in its context, and reads<br />

between the lines. Page 17<br />

in conversation with Henri<br />

Cole, she shares some of<br />

her thoughts on Mies van<br />

der Rohe’s building and<br />

how she conceived the<br />

work during her year at<br />

the Academy. Page 15<br />

Ward Just<br />

Preview of a novel-in-progress<br />

he began to write in Berlin Page 26<br />

On the Waterfront<br />

Press reviews of our program Page 21<br />

Sneak Preview<br />

The Fall <strong>2001</strong> Fellows Page 25<br />

The BerlinJournal<br />

A Newsletter from the American Academy in Berlin<br />

Published at the Hans Arnhold Center<br />

Number Two · <strong>Summer</strong> <strong>2001</strong><br />

Edited by Gary Smith<br />

•<br />

Managing Editors:<br />

Teresa Go · Miranda Robbins<br />

Contributing Editors:<br />

Becky Gilbert · Heidi Philipsen<br />

Illustrations: Natascha Vlahovic<br />

Design: Hans Puttnies<br />

Advertising: Renate Pöppel<br />

Subscription Manager: Christian Oelze<br />

Email: journal@americanacademy.de<br />

Subscriptions: $15 per annum<br />

All Rights Reserved<br />

Contributors<br />

to this issue<br />

Henri Cole is Fannie Hurst Poet-in-Residence<br />

at Brandeis University. He was a Berlin Prize<br />

Fellow in the fall of 2000. Artist Jenny Holzer<br />

lives and works in Hoosick, New York.<br />

Gerald Feldman who was a Berlin Prize Fellow<br />

in 1998, directs the Institute of European<br />

Studies at University of California, Berkeley.<br />

He is preparing a major study, History of the<br />

Allianz Insurance Company.<br />

Richard C. Holbrooke has served as USPermanent<br />

Representative to the UN and Ambassador<br />

to Germany. He is partner and Vice<br />

Chairman at Perseus LLC, and Chairman of<br />

the American Academy.<br />

Ward Just lives alternately in Vineyard<br />

Haven and in Paris. The political novelist<br />

and former foreign correspondent was a<br />

Berlin Prize Fellow in the spring of 1999.<br />

Charles Maier is Krupp Professor of European<br />

Studies and Director of the Center for European<br />

Studies at Harvard University and<br />

chairs the Academy’s Berlin Prize Committee.<br />

The American Academy<br />

in Berlin<br />

Executive Director<br />

Gary Smith<br />

Office Manager, N.Y.<br />

Jennifer Montemayor<br />

External Affairs Director<br />

Renate Pöppel<br />

Program Director<br />

Paul Stoop<br />

Fellows Services Director<br />

Marie Unger<br />

Fellows Selection Coordinator<br />

Teresa Go<br />

The American Academy in Berlin<br />

Am Sandwerder 17-19 · 14109 Berlin<br />

Tel. (+ 49 30) 80 48 3-0<br />

Fax (+ 49 30) 80 48 3-111

AMERICAN ACADEMY<br />

The Notebook of the Academy<br />

Leadership in New York<br />

The Academy Welcomes Robert H. Mundheim<br />

hen founding President Everette Dennis left to help establish a<br />

W new foundation, the American Academy was poised to enter its<br />

second phase, a period of consolidation. Our new President, Robert H.<br />

Mundheim, is impeccably qualified to help us meet the challenges ahead.<br />

These include sharpening our academic profile through a refinement of<br />

the prize selection process, professionalizing the entrepreneurial management,<br />

and making the institution, which has already received major<br />

President Robert H. Mundheim<br />

media coverage, even more familiar<br />

to academics, cultural leaders, and<br />

professional decision makers.<br />

It was Lloyd Cutler who proposed<br />

drafting Bob Mundheim, a distinguished<br />

attorney and financial<br />

expert whom he had worked with<br />

during the Carter Administration<br />

(and unsuccessfully tried to recruit<br />

into his law firm several times over<br />

the years). Their closest collaboration<br />

had been in the wake of the<br />

Iranian hostage crisis, as part of a<br />

team that had improbably »negotiated<br />

the return of our Iranian hostages<br />

on honorable and advantageous<br />

terms in the most complex, delicate,<br />

and exciting financial transactions<br />

of modern times.«<br />

An Ideal<br />

Spiritus Rector<br />

Mundheim had become an equally<br />

effective Dean of the University of<br />

Pennsylvania Law School, where he<br />

has taught since 1965, and a much<br />

sought after general counsel, who<br />

after 1992 participated in the turnaround<br />

of Solomon Brothers.<br />

Mundheim’s career is marked<br />

by accomplishment in the private<br />

and public sectors as well as in the<br />

academic world – thus making him<br />

an ideal spiritus rector for an institution<br />

that demands keen intellectual<br />

sensibilities as well as the ability to<br />

deploy the considerable corporate<br />

and governmental experience of its<br />

Board of Trustees.<br />

Born in Hamburg in 1933, Robert<br />

Mundheim’s career as an attorney<br />

has spanned over forty years since<br />

his graduation from Harvard Law<br />

School in 1957. Those years included<br />

an early stint in the Kennedy<br />

Administration as a special counsel<br />

to the Securities and Exchange<br />

Administration, many years as the<br />

University Professor of Law and<br />

Finance at the University of Pennsylvania,<br />

General Counsel to Treasury<br />

Secretaries Michael Blumenthal<br />

and William Miller in the Carter<br />

Administration, and Co-Chairman<br />

of the New York law firm Fried,<br />

Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson.<br />

Currently Of Counsel at Shearman<br />

& Sterling – a law firm with four offices<br />

in Germany – Mundheim has<br />

always committed a significant<br />

amount of time to supporting nonprofit<br />

institutions in leading roles.<br />

At present he is President of the<br />

Appleseed Foundation, a trustee<br />

of the New School University, and a<br />

director of the Salzburg Seminar.<br />

He himself says that he has »always<br />

felt that it is important for active<br />

practitioners to find time to give to<br />

public interest work.«<br />

Academy Chairman Richard Holbrooke,<br />

himself a negotiator of fabled<br />

ability, stated that »there is no<br />

question that the American Academy<br />

in Berlin has made a coup of<br />

major proportion by bringing a<br />

man of Bob Mundheim’s ability<br />

and background to help negotiate<br />

the next phase of its existence. His<br />

vast experience and talents will<br />

help ensure that the American Academy<br />

becomes the preeminent, and<br />

certainly most effective voice in<br />

transatlantic cultural and intellectual<br />

affairs.«<br />

4

American Generosity<br />

Resounds in Berlin<br />

Arts Patron Vilar Endows Music Fellowship Program<br />

THE BERLIN JOURNAL<br />

our months after delivering<br />

a talk on philanthropy<br />

F<br />

and opera at the Hans Arnhold<br />

Center, Alberto Vilar has joined the<br />

American Academy’s Board of<br />

Trustees and underwritten a longterm<br />

music fellowship program.<br />

Presenting his generous donation<br />

of over four million dollars, Vilar<br />

said that his »goal is to extend the<br />

reach of the classical performing<br />

arts and make them available to a<br />

larger audience than ever before.<br />

Through this gift, I hope to introduce<br />

a new generation of outstanding<br />

American artists to Berlin’s<br />

musical audiences. At the same time,<br />

I am confident that the American<br />

musical repertoire will benefit immensely<br />

by having some of its best<br />

and brightest stars learn from and<br />

exchange ideas with the luminaries<br />

of Berlin’s musical scene.« Beginning<br />

this fall, the Alberto Vilar<br />

Music Fellowships will bring exceptional<br />

American composers of classical<br />

music, performing artists, and<br />

experts working in music and technology<br />

to Berlin each semester.<br />

In addition, an annual Alberto<br />

Vilar Distinguished Fellowship will<br />

be awarded to a performer or composer<br />

for a short-term residency in<br />

Berlin to work with a major Berlin<br />

orchestra or other musical venue.<br />

Both programs will deepen the<br />

Academy’s relationships with Berlin’s<br />

major musical institutions. An<br />

outstanding selection jury – including<br />

Michael Kaiser of the John F.<br />

Kennedy Center for the Performing<br />

Arts, Lorin Maazel of the Bavarian<br />

Alberto Vilar and Conductor Daniel Barenboim<br />

in the Academy’s Library<br />

Radio Symphony Orchestra, Tod<br />

Machover of the Massachusetts Institute<br />

of Technology, Marta Casals<br />

Istomin of the Manhattan School<br />

of Music, and Gary Graffman of the<br />

Curtis Institute of Music – will ensure<br />

the program’s success.<br />

Alberto Vilar founded Amerindo<br />

Investment Advisors, Inc. in 1980<br />

to manage institutional portfolios<br />

exclusively invested in emerging<br />

technology growth stocks. No one<br />

would have known at that time how<br />

auspicious this would be for the future<br />

of classical music. Many of the<br />

companies Amerindo significantly<br />

invested in – Microsoft, Oracle,<br />

Cisco, America Online, Yahoo!, and<br />

ebay – became household names.<br />

Continued on Page 20<br />

MIKE MINEHAN<br />

ichard C. Holbrooke’s<br />

R<br />

return as Chairman of the<br />

American Academy in Berlin has<br />

brought two immediate benefits.<br />

First, Ambassador Holbrooke provides<br />

the Academy with remarkable<br />

visibility within the highest<br />

echelons of the political, diplomatic,<br />

and corporate worlds. He is,<br />

moreover, an energetic and effective<br />

champion, recently cementing<br />

an agreement with the philanthropist<br />

Alberto Vilar to ensure that<br />

music will be a cornerstone in the<br />

Academy's program.<br />

Ambassador Holbrooke has had<br />

a distinguished career in public service.<br />

In the past decade, he has served<br />

as the United State’s Ambassador<br />

to Germany (1993-1994) and the<br />

U.S. Permanent Representative to<br />

the United Nations, a post from<br />

which he stepped down early this<br />

year. A cabinet member in the Clinton<br />

administration, he played a<br />

A Foreign Affair<br />

Founder Richard C. Holbrooke Returns<br />

as Academy Chairman<br />

5<br />

central role in shaping American<br />

foreign policy as well as the nation’s<br />

response to such humanitarian crises<br />

as AIDS. As Assistant Secretary<br />

of State for Europe (1994-1996), he<br />

was the chief architect of the 1995<br />

Dayton Peace Accords that ended<br />

the war in Bosnia, later serving as<br />

President Clinton's Special Envoy<br />

to Bosnia and Kosovo. As a private<br />

citizen he also served as a pro-bono<br />

Special Envoy to Cyprus.<br />

In the corporate world, Ambassador<br />

Holbrooke has held senior<br />

positions at two leading Wall Street<br />

firms, Credit Suisse First Boston<br />

and Lehman Brothers, in addition<br />

to an important position at American<br />

Express. This year Ambassador<br />

Holbrooke has taken on several<br />

major tasks in both the private and<br />

public sectors.<br />

He is building upon his Wall Street<br />

experience in joining Perseus LLC,<br />

the Washington-based merchant<br />

bank founded by financier Frank<br />

Pearl, as partner and Vice Chairman.<br />

He also joined the board of AIG and<br />

the advisory councils of Coca-Cola<br />

and AOL Time Warner. Ambassador<br />

Holbrooke continues to lead in<br />

the fight against AIDS, an issue to<br />

which he gave priority during his<br />

tenure at the U.N, as the unpaid<br />

President and CEO of the Global<br />

Business Council on H.I.V. & AIDS.<br />

He belongs to several major nonprofit<br />

boards, including the National<br />

Endowment for Democracy,<br />

the Museum of Natural History in<br />

New York, the International Rescue<br />

Committee, and Refugees International,<br />

chairing the latter two. He is<br />

also a Counselor at the Council on<br />

Foreign Relations, where he is preparing<br />

a book-length study of American<br />

diplomacy.<br />

Ambassador Holbrooke’s visit to<br />

the American Academy this Spring<br />

was accompanied by a flurry of interviews<br />

and raised a host of foreign<br />

policy questions affecting European-<br />

U.S. relations. Among these were<br />

missile defense (covered in the Berliner<br />

Zeitung and on wire services);<br />

the torpidity of the E. U. bureaucracy<br />

(The Financial Times); and the<br />

implications for Europe of the new<br />

Bush administration’s foreign policy<br />

(Der Spiegel). In a public interview<br />

held at Continued on Page 25

Capital Infusion<br />

J. P. Morgan Underwrites<br />

Financial Policy Focus in Berlin<br />

s the American Academy<br />

A<br />

enters its fourth year, public<br />

policy issues will become an increasingly<br />

important part of its profile.<br />

It attained a major step toward defining<br />

this profile when it announced,<br />

together with the global investment<br />

bank J. P. Morgan, the establishment<br />

of the J. P. Morgan International<br />

Prize in Financial Policy<br />

and Economics.<br />

The annual prize is the first of its<br />

kind in the realm of finance. It will<br />

allow American economists and financial<br />

professionals to pursue a<br />

research project and interact with<br />

German corporate and government<br />

officials on significant financial policy<br />

issues facing Germany, Europe,<br />

and America.<br />

While in residence at the Hans<br />

Arnhold Center for terms ranging<br />

from four weeks to one semester,<br />

J. P. Morgan Fellows will lecture and<br />

help the Academy expand its forum<br />

for economic and financial policy<br />

issues. Announcing the new fellowship<br />

program at a press conference<br />

on Wall Street in February, Academy<br />

Chairman Richard C. Holbrooke<br />

underscored both the Academy’s<br />

mission of strengthening German-<br />

American relations and the prize’s<br />

ability to forge a much needed link<br />

between academic knowledge and<br />

practical relevance.<br />

»We are very pleased that J.P.<br />

Morgan has taken the lead in supporting<br />

this initiative, as we feel it is<br />

important to recognize the contribution<br />

made by those in the field of<br />

finance to our social and cultural<br />

environment. By bringing such expertise<br />

to Berlin on a regular basis,<br />

we are underscoring the increasing<br />

role of Germany’s capital in establishing<br />

policy in these areas for<br />

their nation as well as the European<br />

Union.«<br />

Walter Gubert, Chairman of<br />

the J.P. Morgan Global Investment<br />

Bank, articulated the strategic relevance<br />

of the fellowship for the bank’s<br />

intellectual self-understanding:<br />

The Hans Arnhold Center hosted a symposium<br />

which brought a team of medical experts from the<br />

Mayo Clinic together with leading health care experts<br />

from throughout Germany. Co-moderated<br />

by the President of the German Science Council,<br />

Prof. Karl Max Einhäupl, and Mayo Trustee Prof.<br />

Rolland E. Dickson, the symposium had two ambitions:<br />

first, to articulate the Mayo Clinic’s particular<br />

health care opportunities for a German specialist<br />

public, and second, to create a high-level transatlantic<br />

dialogue in key policy areas.<br />

During the day-long convocation, initiated and<br />

generously made possible by the Anna-Maria and<br />

Stephen Kellen Foundation, the visitors engaged<br />

around seventy specialists on issues such as the division between the private and public<br />

sector; the need for strategies of interaction between research, education, and health care;<br />

the implications of research in aging and geriatric health; and a host of diagnostic, therapeutic,<br />

and ethical issues raised by genomic practice.<br />

The differences in American and German frames of reference was emphasized by Prof.<br />

Stefan Mundlos (Humboldt University, Institute for Medical Genetics), who referred to the<br />

lessons of Germany’s specific history, and warned of the potential stigmatization of certain<br />

groups as they become more defined by shared genetic traits. The intense and productive<br />

exchanges during the symposium underscored the importance of continuing to focus on<br />

health policy questions in transatlantic dialogue.<br />

AMERICAN ACADEMY<br />

»Creating this prize extends our<br />

expertise in finance from client activity<br />

to the public and academic<br />

realms in Germany. As a worldwide<br />

investment bank we recognize the<br />

effects of increased globalization<br />

and the importance of bringing<br />

countries in Europe and America<br />

closer together in all aspects.«<br />

Academy President Robert Mundheim<br />

especially thanked Kurt Viermetz<br />

– a founding trustee of the<br />

American Academy who, in his<br />

many years at J.P. Morgan, has been<br />

the most important German in U.S.<br />

banking – for his help in bringing<br />

about an especially timely and promising<br />

collaboration.<br />

Possible projects might compare<br />

Anglo-Saxon and continental models<br />

on regulatory issues, for example<br />

or investigate other areas of direct<br />

relevance to Berlin policymaking,<br />

including global and transatlantic<br />

exchange rates; the convergence of<br />

European capital markets and stock<br />

exchanges; national and pan-European<br />

tax and pension reform; competing<br />

policy models for economic<br />

restructuring; and European integration.<br />

A distinguished panel of experts<br />

reviews applicants for the prize.<br />

It includes: Rüdiger Dornbusch of<br />

the Massachusetts Institute of<br />

Technology; Benjamin Friedman<br />

of Harvard; Richard J. Herring, of<br />

the University of Pennsylvania’s<br />

Wharton School; Horst Siebert,<br />

of the Kiel Institute of World Economics;<br />

and Charles Maier, of<br />

Harvard University.<br />

Trustees On Board<br />

Gregorian, Kornblum, Pozen, and Vilar Elected<br />

our new board members<br />

F<br />

– Vartan Gregorian, John C.<br />

Kornblum, Robert C. Pozen, and<br />

Alberto Vilar – will strengthen the<br />

American Academy’s Board of Trustees<br />

and support its efforts in the<br />

academic, foundation, business<br />

and philanthropic communities.<br />

Each of the new trustees has a history<br />

of commitment to non-profit<br />

institutions as well as considerable<br />

leadership experience. Vartan<br />

Gregorian, President of the Carnegie<br />

Corporation of New York, and former<br />

president of both the New<br />

York Public Library and Brown<br />

University, brings to the board his<br />

invaluable background in cultural<br />

and academic institutions, in addition<br />

to an intimate knowledge of<br />

foundations.<br />

John C. Kornblum, a former career<br />

foreign service officer and an<br />

abiding supporter of the Academy<br />

during his term as U.S. Ambassador<br />

to Germany, will continue to<br />

advise the Academy on public policy<br />

and business matters from Berlin,<br />

where he will remain as Chairman<br />

of the investment bank Lazard<br />

& Co. GmbH. Ambassador Kornblum<br />

recently contributed a collection<br />

of four hundred volumes to the<br />

Hans Arnhold Center’s library.<br />

Robert C. Pozen, a chief investment<br />

executive of Fidelity Investment,<br />

brings an experience in different<br />

worlds that is extremely attractive<br />

to the Academy. He taught<br />

law at New York University, served<br />

as associate general counsel to the<br />

Securities & Exchange Commission,<br />

and practiced law in Washington<br />

before joining Fidelity Investments.<br />

The philanthropist, music lover,<br />

and financier Alberto Vilar, has<br />

already made an contribution of<br />

lasting impact to the Academy.<br />

Vilar, founder of Amerindo Investment<br />

Advisors, recently donated<br />

four million dollars to establish a<br />

long-term program for classical<br />

music. The gift has been reported<br />

extensively in the German press<br />

and is eagerly looked forward to<br />

by Berlin’s musical community.<br />

6

THE BERLIN JOURNAL<br />

Life and Letters at the Hans Arnhold Center<br />

Profiles in Scholarship<br />

The Berlin Projects<br />

of the Academy’s Springtime Fellows<br />

The Class of Spring <strong>2001</strong> (from left): Ellen Hinsey, Christoph Wolff, Margaret L. Anderson,<br />

Stephanie Snider, James Sheehan, Kathleen N. Conzen, Mark Harman, Hillary Brown, Caroline<br />

Fohlin and Jeffrey Eugenides.<br />

Margaret L. Anderson<br />

After extensive work on the political<br />

history of imperial Germany,<br />

including the themes of Kulturkampf<br />

and democratic institutions, historian<br />

Margaret Lavinia Anderson of<br />

the University of California at Berkeley<br />

found a new theme in an unlikely<br />

source: a historical novel by Franz<br />

Werfel. The Forty Days of Musa Dagh<br />

(1933) fictionalizes the attempt of<br />

the German Protestant pastor, Johannes<br />

Lepsius, to prevent the destruction<br />

of the Armenians during<br />

the First World War by pleading<br />

with Enver Pasha, the Ottoman<br />

War Minister. Lepsius, who later<br />

edited a forty-volume documentation<br />

of German foreign policy, had<br />

a long history of commitment to<br />

the Armenian cause. While at the<br />

Academy, Anderson drew on extensive<br />

archives in Berlin and Halle<br />

to document Lepsius’s efforts on<br />

behalf of the Armenians. Her study<br />

explores both the history of the early<br />

human rights movement and its<br />

entanglement with imperialism<br />

and decolonization.<br />

MIKE MINEHAN<br />

7<br />

Martin Bresnick<br />

Composer Martin Bresnick,<br />

whom Fanfare Magazine has called<br />

an »eminence grise to some of the<br />

more successful younger composers<br />

around« and »a champion synthesizer<br />

of disparate materials,« took a<br />

leave from the Yale School of Music<br />

in 1998, when he received the first<br />

Charles Ives Living Award, a threeyear<br />

grant from the composer’s<br />

estate, administered by the American<br />

Academy of Arts and Letters.<br />

Bresnick’s Berlin residency coincided<br />

with the release of a two-disc<br />

set of his works, which the New York<br />

Times described as »tough, thorny,<br />

clear, elegant, thoughtful, and difficult<br />

to pin down.« Bresnick’s Berlin<br />

Prize also brought his musical »significant<br />

other« to the Hans Arnhold<br />

Center: Australian concert pianist<br />

Lisa Moore, a gifted interpreter<br />

of his composed work, who gave<br />

several performances while at the<br />

Academy. She also performed an<br />

evening with poet-in-residence<br />

Ellen Hinsey.<br />

Hillary Brown<br />

Architect and native New Yorker<br />

Hillary Brown used her Bosch Public<br />

Policy Fellowship at the American<br />

Academy to study European environmentally<br />

progressive building<br />

legislation and administration. In<br />

recent years, Germany has led Europe<br />

in setting forward models of<br />

sustainable development, among<br />

them the ecological approach to<br />

the design and construction of<br />

buildings. A sophisticated suite of<br />

public policies, performance standards,<br />

and regulatory measures are<br />

influencing the form, techniques,<br />

and aesthetics of architecture.<br />

Though the United States lags<br />

significantly behind Europe in promulgating<br />

equivalent policies,<br />

Brown herself has fought hard to<br />

increase awareness of them. She is a<br />

founder of the Office of Sustainable<br />

Design and Construction in New<br />

York City, which works to introduce<br />

energy- and resource-efficient features<br />

into the city’s public facilities.<br />

Brown brought to Berlin her fifteenyear-long<br />

career in city government,<br />

a decade of professional architecture<br />

practice, and years of teaching<br />

at the Yale and Columbia graduate<br />

schools of architecture.<br />

Judith Butler<br />

Philosopher Judith Butler, a leading<br />

theorist on gender and identity<br />

issues, returned to Berlin this spring<br />

as a Distinguished Senior Visitor at<br />

the Academy. In a talk at the Hans<br />

Arnhold Center she probed contemporary<br />

debates on new forms of<br />

kinship and gay marriage. She also<br />

lectured on »intersexual allegories«<br />

at the Freie Universität Berlin and<br />

held a public conversation with<br />

choreographer Sasha Waltz about<br />

the piece »Bodies« performed at<br />

the Schaubühne. Butler is a professor<br />

of comparative literature at the<br />

University of California, Berkeley.<br />

Her most recent book, Antigone’s<br />

Claim has just been published in<br />

German by Suhrkamp.

Kathleen N. Conzen<br />

In 1817, American Secretary of<br />

State John Quincy Adams warned<br />

potential German immigrants that<br />

they »must cast off the European<br />

skin, never to resume it, or be disappointed<br />

in every expectation of<br />

happiness as Americans.« University<br />

of Chicago historian Kathleen<br />

N. Conzen has dedicated her career<br />

to examining the acculturation of<br />

the six million Germans who arrived<br />

in the United States before 1916.<br />

In particular, she studies the extent<br />

to which areas as diverse as religious<br />

life, agrarian ideology, urban<br />

mass culture, and political attitudes<br />

were influenced by German culture.<br />

Two published works, Immigrant<br />

Milwaukee: Accomodation and<br />

Community in a Frontier City, 1836-<br />

1860 and Making Their Own America:<br />

Assimilation Theory and the German<br />

Peasant Pioneer are case studies<br />

in the cultural cross-fertilization of<br />

mass immigration. While at the<br />

Hans Arnhold Center, Conzen collaborated<br />

with Willi Paul Adams<br />

of the Freie University’s Kennedy<br />

Institute on a compendium of texts<br />

documenting German-American<br />

political debates between the American<br />

Revolution and 1916.<br />

Jeffrey Eugenides<br />

When writer Jeffrey Eugenides<br />

came to Berlin two years ago under<br />

the auspices of the DAAD, the success<br />

of his 1993 debut novel was<br />

still fresh. Even J. K. Rowling, author<br />

of the famed Harry Potter books,<br />

revealed that »the last great book I<br />

read was The Virgin Suicides,« one<br />

encomia among many for a novel<br />

that had already won distinguished<br />

fiction awards from the Whiting<br />

Foundation, and the American<br />

Academy of Arts and Letters among<br />

others. New York Times critic Michiko<br />

Kakutani described the novel as<br />

»by turns lyrical and portentous,<br />

ferocious and elegiac« and called it<br />

»a small but powerful opera in the<br />

unexpected form of a novel.« His<br />

stories were included in Granta’s<br />

collection Best of Young American<br />

Novelists and in The New Yorker’s<br />

special issue Twenty Writers for the<br />

21st Century. During Eugenides’<br />

time in Berlin, the new German<br />

capital has begun to insinuate itself<br />

into his work, both in review essays<br />

and short stories. His soon-to-becompleted<br />

second novel takes the<br />

reader far beyond the city, but the<br />

plot’s genetic underpinnings were<br />

time and again at the forefront of<br />

public discussions at the Hans Arnhold<br />

Center during his year at the<br />

Academy.<br />

Caroline Fohlin<br />

That financial systems are shaped<br />

in part by the influence of political<br />

and legal environments and<br />

even historical accident is a key premise<br />

underlying the research of Cal-<br />

Tech economist Caroline Fohlin.<br />

Since completing her doctorate at<br />

Berkeley in 1994, she has published<br />

widely on the history of German<br />

banking during industrialization.<br />

Most recently she expanded her<br />

research on the rise of interlocking<br />

AMERICAN ACADEMY<br />

directorates in imperial Germany<br />

into a database that details relationships<br />

in corporate governance<br />

between German industry and<br />

commercial banking in Germany<br />

between 1895 and 1912. She simultaneously<br />

pursued a broader historical<br />

study of the implications of<br />

financial system design.<br />

While at the American Academy<br />

she worked on two monographs,<br />

New Perspectives on the Universal<br />

Banking System in the German Industrialization<br />

and Financial System<br />

Design and Industrial Development:<br />

International Patterns in Historical<br />

Perspective.<br />

Mark Harman<br />

Reading great literature in translation<br />

is an act of faith; one must<br />

trust that the work is true both to<br />

the author’s language and spirit.<br />

The finesse required of the translator<br />

is perhaps most appreciable<br />

when two markedly different interpretations<br />

of the same text are compared.<br />

Translator and literary scholar<br />

Mark Harman spent two terms<br />

Martin Bresnick and Lisa Moore<br />

Break in our Bösendorfer<br />

ELLEN HINSEY<br />

at the Academy pursuing the enigma<br />

of Franz Kafka, an author to whom<br />

he had already devoted considerable<br />

attention. Harman’s translation<br />

of The Castle was hailed by The<br />

Boston Review as »truer to Kafka’s<br />

imagination than the earlier version,«<br />

and he received the first Lois<br />

Roth Award from the Modern Language<br />

Association in 1999 for his<br />

translation work.<br />

A professor of German and English<br />

at Elizabethtown College, he<br />

has published critical essays on<br />

other modernists as well, James<br />

Joyce not least among them. At the<br />

Academy, Harman shared his<br />

theory that a rich »autobiography«<br />

of Kafka may be gleaned through<br />

an attentive and critical reading of<br />

his fiction.<br />

Ellen Hinsey<br />

Paris and Berlin are cities of abiding<br />

resonance for American writers,<br />

and to some, they serve as portals<br />

to other destinations as well.<br />

Paris-based poet Ellen Hinsey,<br />

whose poems are marked by a preoccupation<br />

with Eastern European<br />

literature and a passion for travel<br />

and languages, used her stay at the<br />

Hans Arnhold Center to work on a<br />

first novel.<br />

Hinsey’s poems have appeared<br />

in numerous newspapers and journals,<br />

among them The New Yorker,<br />

New York Times, The Paris Review,<br />

and The Missouri Review. Her first<br />

volume of poetry Cities of Memory<br />

won the Yale Younger Poets Prize<br />

in 1996. Fellow-poet James Dickey<br />

has written admiringly: »with her<br />

quiet and deep involvement in<br />

other places and tongues, her truerunning<br />

imagination, Ellen Hinsey<br />

comes to rest in many ways and<br />

places. Though not native-born to<br />

these, she is at the center of them<br />

just the same, by virtue and talent<br />

one of the best kinds of human<br />

being: the perceptive voyager, the<br />

sympathetic and vivid stranger.«<br />

Her second volume of poetry,<br />

Vita contemplativa, is forthcoming<br />

this fall.<br />

8

THE BERLIN JOURNAL<br />

Christopher Kojm<br />

It has become commonplace for<br />

Europeans to question America’s<br />

dominant role in international affairs.<br />

The nation’s economic, technological<br />

and military advantages,<br />

not to mention its cultural influence<br />

on adversaries and allies alike, are<br />

impressive – and unsettling – to<br />

many. As a Bosch Public Policy Fellow<br />

at the Academy, Christopher<br />

Kojm investigated European perceptions<br />

and responses to this<br />

American hegemony and its implications<br />

for American policymakers.<br />

Mr. Kojm, a former Bosch Fellow<br />

with extensive policy experience in<br />

Washington, currently serves as<br />

Deputy Assistant Secretary of State<br />

for Intelligence Policy and Coordination<br />

in the State Department’s<br />

Bureau of Intelligence & Research.<br />

Kojm’s study is especially timely<br />

given the recent change of administrations,<br />

which has dramatically<br />

effected the European view of American<br />

power and altered its perception<br />

of the degree to which the<br />

European Union and European<br />

governments influence American<br />

foreign policy.<br />

Colette Mazzucelli<br />

Philosophers, writers, and policy<br />

makers have debated the geopolitical<br />

potential of cyberspace almost<br />

since the term was first coined by<br />

William Gibson in 1984. Bosch<br />

Public Policy Fellow Colette Mazzucelli<br />

draws on this debate and<br />

applies it to a strategic area of government<br />

interest in her project<br />

Educational Diplomacy via the Internet:<br />

Defining the American Interest<br />

within a Transatlantic Policy Dialogue<br />

on Kosovo.<br />

Mazzucelli holds a doctorate<br />

in comparative government from<br />

Georgetown and serves as Co-President<br />

of the Robert Bosch Alumni<br />

Association. Her seminar at the<br />

Hans Arnhold Center provided a<br />

glimpse into how state-of-the-art<br />

technologies such as video conferencing<br />

and internet streaming<br />

OBrother,WhereArtThou<br />

Sander L. Gilman in Search of Jurek Becker<br />

The life of Jurek Becker spanned six decades of sweeping political changes<br />

in his homeland and in Germany. Born in Lódz, Poland in 1937, Becker<br />

witnessed major events of the twentieth century; among the defining phases<br />

in his life were his childhood in the Lódz ghetto, the concentration camp at<br />

Ravensbrück, life in post-war East Berlin, and West-German exile.<br />

By the time of his death in 1997, Jurek Becker had authored numerous<br />

novels and screenplays, including his best-known work, Jacob the Liar, published<br />

in 1968 and acclaimed on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Becker was<br />

a friend of Berlin Prize Fellow Sander Gilman, who spent his year at the<br />

Hans Arnhold Center preparing a biography of him. Gilman’s investigation<br />

adds a personal dimension to his scholarly work.<br />

The cultural and literary historian Sander Gilman is himself a prolific<br />

writer, to date the author or editor of over sixty books. His most recent monograph,<br />

Making the Body Beautiful: A Cultural History of Aesthetic Surgery was<br />

published by Princeton University Press in 1999.<br />

For twenty-five years he was a member of the humanities and medical faculties<br />

at Cornell University and for six years of the faculty of the University<br />

of Chicago. Since Fall 2000 he has been Distinguished Professor of the Liberal<br />

Arts and Medicine at the University of Illinois at Chicago and Director<br />

of its Humanities Lab, a new type of structure that will further collaborative<br />

research and training in the humanities.<br />

Fiona MacCarthy characterized Making the Body Beautiful in the New York<br />

Review of Books as »a strange, macabre and often richly comic story of shifting<br />

desires. His book shows a dazzling European erudition.« The breadth<br />

of Gilman’s knowledge was not lost on his colleagues at the Hans Arnhold<br />

Center, who nicknamed him »The Internet« because of his uncanny ability<br />

to answer questions intelligently on any subject. The biography of Becker is<br />

due to appear next fall.<br />

9<br />

MATTHEW GILSON<br />

enable colleagues in cities from<br />

New York to and Pristina to confer<br />

on breaking crises, specifically the<br />

recent escalation in Macedonia.<br />

Adam Posen<br />

Adam Posen, Senior Fellow at the<br />

Institute for International Economics<br />

in Washington (IIE), has been<br />

involved in the study of the German<br />

economy since working at the<br />

Bundesbank and Deutsche Bank as<br />

a Robert Bosch Foundation Fellow<br />

in 1992. This year, as a Bosch Public<br />

Policy Fellow at the Academy, he<br />

completed an investigation of Germany’s<br />

persistently high rate of unemployment<br />

and the degree to<br />

which this problem has influenced<br />

German international economic<br />

policies. Before joining the IIE, Posen<br />

spent three years at the Federal<br />

Reserve Bank of New York, analyzing<br />

German economic developments<br />

for Federal Reserve Board<br />

members and top management<br />

there.Mostrecently,hehasauthored<br />

Restoring Japan’s Economic Growth<br />

and co-authored Inflation Targeting:<br />

Lessons from the International<br />

Experience. Another work, Disciplined<br />

Discretion: Monetary Targeting<br />

in Germany and Switzerland (coauthored),<br />

is the most widely-cited<br />

study in English of German economic<br />

policy and has been excerpted<br />

in Bundesbank publications. The<br />

monograph resulting from his stay<br />

at the Hans Arnhold Center, Germany<br />

in the World Economy after<br />

EMU, will be presented this fall at<br />

the Academy.<br />

James Sheehan<br />

Distinguished Stanford historian<br />

and DaimlerChrysler Fellow James<br />

Sheehan has already turned two<br />

previous fellowship years in Germany<br />

into major works: German<br />

History 1770-1866 (supported by<br />

the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin)<br />

and Museums in the Modern Art<br />

World: From the End of the Old Regime<br />

to the Rise of Modernism (Humboldt<br />

Prize). Continued on page 24

AMERICAN ACADEMY<br />

Mission Possible<br />

Peacekeeping and the United Nations<br />

By Richard C. Holbrooke<br />

Ambassador Richard C. Holbrooke, returning in<br />

May 2000 from a UN tour of Africa – including the<br />

Congo, Sierra Leone, and Ethiopia – stopped by<br />

Germany to make the case for humanitarian intervention.<br />

Indeed, it is among the most urgent issues<br />

in foreign policy today and will become a public<br />

policy focus in future programs at the Academy.<br />

O<br />

ne of the new issues that will bind<br />

our countries together is our mutual<br />

interest in peacekeeping. Peacekeeping,<br />

especially UN peacekeeping, is being challenged<br />

today in a fundamental way.<br />

I arrived here directly from Asmara, Eritrea<br />

and Addis Ababa in Ethiopia after an intense,<br />

grueling eight-day, eight-nation UN Security<br />

Council Mission to seven African states. Our main<br />

objective on the mission originally was to assess<br />

the prospects for deploying UN peacekeepers in<br />

the Congo, but it was framed by two other crises<br />

– in Sierra Leone and the Horn of Africa. I will<br />

assert that what happens in this part of the world<br />

cannot be ignored by Americans or by Europeans<br />

and that a little bit of effort early is a lot better<br />

than a lot of effort later.<br />

Many say that while such crises are terrible,<br />

there is nothing we can or should do about them.<br />

But I believe that on every level – political, humanitarian,<br />

strategic, financial, moral – we cannot<br />

turn away. Financially the cost of the consequences<br />

of a war – famine, the need for refugee<br />

relief and reconstruction, and the grave threat<br />

of spreading disease – is much greater than the<br />

cost of trying to prevent it. From a moral and<br />

humanitarian point of view, we cannot turn<br />

away. From a political point of view, we can<br />

make a difference if we engage.<br />

The UN is many things, but it was conceived<br />

in the ashes of the war that destroyed Europe to<br />

be primarily and centrally a conflict prevention<br />

and conflict resolution organization. This is still<br />

the core responsibility of the UN. The stakes are<br />

very high in Sierra Leone and the Congo and Kosovo<br />

and East Timor. How the UN and the world<br />

community respond to the situations there will<br />

have huge ramifications for peacekeeping<br />

throughout the world and determine whether<br />

whether the world looks to the UN at all to do<br />

peacekeeping. There has been extensive criticism<br />

of the UN effort in Sierra Leone. Both policy<br />

makers and the press are asking tough questions<br />

about whether the UN was prepared for the crisis.<br />

Sierra Leone, like Bosnia before it, is an example<br />

of what happens when the parties to a peace<br />

settlement violate that settlement, wreaking<br />

havoc on everyone – peacekeepers and civilians<br />

alike.<br />

The question is even more fundamental: what<br />

is the future of UN peacekeeping? The world has<br />

a choice in Sierra Leone. And, what happens<br />

there will also affect the UN’s approach to the<br />

Congo, although I believe that decisions on the<br />

Congo should be made independent of, while at<br />

the same time drawing lessons from, the crisis in<br />

The longer the United<br />

Nations fails to live up to its<br />

potential, the longer the<br />

innocents will suffer, the<br />

greater the danger that we<br />

will be sucked in later<br />

Sierra Leone. I want to be clear on another point:<br />

Sierra Leone, the Congo, or Ethopia/Eritrea, appalling<br />

as they are, cannot be viewed as a metaphor<br />

for all of Africa. Despite these legitimately<br />

well-publicized disasters in Africa, there are<br />

plenty of success stories, for example ECOWAS<br />

in the West African states, and the South African<br />

Development Council in Southern Africa.<br />

All of this – the good, the bad, the ugly –<br />

needs to be drawn on in the difficult coming days<br />

and weeks of policy making for the international<br />

community. This a continent which, from a distance,<br />

seems to be aflame from across its entire<br />

breadth but, in fact, is dealing with separable,<br />

discreet, and identifiable crises.<br />

We specifically need to address the Congo,<br />

where history – from King Leopold's ghost to<br />

10<br />

Mobutu’s legacy – hangs heavy over the country.<br />

Perhaps no African state has had more difficulty<br />

in overcoming its past. Last year, under<br />

the leadership of President Chiluba of Zambia,<br />

eight nations came together in his capital, Lusaka,<br />

to sign the Lusaka Peace Accords. It is a good<br />

agreement, an African solution to an African<br />

problem. The UN has committed itself to supporting<br />

it, and part of that commitment will involve<br />

peacekeeping troops.<br />

I certainly do not disagree that UN peacekeeping<br />

has fundamental problems. In Sierra<br />

Leone the UN deployed a force that was too inexperienced<br />

and insufficiently capable. Deployments<br />

were very slow. This troubles me greatly<br />

in regard to the Congo, where both President<br />

Museveni of Uganda and President Kagame of<br />

Rwanda have urgently called for UN troops to<br />

take over Kisangani.<br />

I remain committed to trying to make UN peacekeeping<br />

effective, which if done right, is vital.<br />

It can be successful. We have many examples:<br />

Cyprus today, still divided and beginning the<br />

process of accession to the EU, would not be the<br />

peaceful (but tense) island it is today were it not<br />

for UN forces. The UN peacekeepers played indispensable<br />

roles in bringing stability, independence,<br />

and progress to other areas like Eastern<br />

Slovenia and Croatia. They played critical roles<br />

in Namibia, Macedonia, Mozambique, and I<br />

commend them highly for the work they are<br />

doing in East Timor.<br />

The UN is certainly not going to be the answer<br />

to every crisis. Sometimes as in Bosnia, the bulk<br />

of the forces are not UN. The initial deployment<br />

in East Timor, for example, was not a UN peacekeeping<br />

deployment. Although authorized by<br />

the UN, it was a regular military force led by a<br />

very powerful Australian contingent, backed up<br />

by British, French, American, Philippine and<br />

Korean troops. When they had things under<br />

control, they transitioned from a multinational<br />

force to a UN force. Some of the same troops<br />

stayed and put on blue berets.<br />

The UN and regional leaders should and must<br />

work hand in glove. Sometimes regional organizations<br />

should take the lead with UN support,

as in East Timor. In other cases, the UN should<br />

lead with regional support. Among the world's<br />

regional organizations, there is no doubt about<br />

which one is the most powerful and the most<br />

effective. It is NATO. The Atlantic Alliance remains<br />

indispensable to stability.<br />

The question for us is not whether or not that<br />

Alliance is strained. It is not. It is a strong organization<br />

and the strongest strategic relationship<br />

in the world. It has survived every challenge of<br />

the Cold War and made a transition to a post-<br />

Cold-War context, adding three new members<br />

and taking on incredibly difficult responsibilities<br />

in Bosnia and Kosovo. There are many crises<br />

in the world. The Atlantic Alliance is not one of<br />

them. On the contrary, Bosnia is one of the great<br />

success stories of international peacemaking<br />

and peacekeeping. The United States, Germany,<br />

France, and the United Kingdom – and<br />

even Russia in the Contact Group, in the Dayton<br />

negotiations, and in the subsequent period –<br />

have kept the peace for five years with no casualties.<br />

Much more slowly than we want but unmistakably,<br />

the country is beginning to knit together.<br />

Germany has, as a result of that effort,<br />

been able to see a sharp reduction in the number<br />

of refugees from the Balkans, so the benefits far<br />

THE BERLIN JOURNAL<br />

outweigh the costs so generously undertaken.<br />

Kosovo, of course, is a much more difficult situation,<br />

but it is much earlier in the process, and a<br />

similar commitment by all the countries involved<br />

is essential for it to succeed. Peace in Kosovo<br />

is far from assured at this point as an enduring<br />

outcome. But, if the United States, Germany,<br />

and our NATO Allies make the commitment,<br />

I am sure that we will be able to persevere.<br />

Africa is not part of the NATO area of responsibility.<br />

Africa is more difficult. It is far away.<br />

Its logistics are harder. The Congo, for example,<br />

is about two-hundred times the size of Kosovo,<br />

and there are no roads. The rivers have silted up,<br />

and there are few communications. No amount<br />

of external United Nations or international forces<br />

can ever bring peace to the Congo. It has to<br />

be the parties themselves, assisted by the international<br />

community. No one is arguing that a<br />

Bosnia/Kosovo-type operation would be desirable<br />

or possible in the Congo. Nonetheless, we<br />

cannot turn away from it. In order to make it<br />

work, the UN Secretariat is going to have to do a<br />

better job.<br />

We will propose to the UN far-ranging reforms<br />

for the way its peacekeeping office is financed,<br />

structured, and administered. Absent the<br />

reform, UN peacekeeping will be on a collision<br />

course. But reform, if carried out, should be<br />

able to deal with the simple fact that demand for<br />

peacekeeping is far outpacing the UN's capacity.<br />

Reform cannot wait. The talk about peacekeeping<br />

reform brings to mind Bismarck’s<br />

famous observation that conquering armies –<br />

or rebel groups for that matter – will not be halted<br />

by the power of eloquence. Words are important<br />

and have meaning, but the time is here<br />

for action.<br />

We should remember that peacekeeping in its<br />

core, whether it is in Bosnia or Kosovo or Cyprus<br />

or East Timor or Africa, is about more than<br />

maintaining the credibility of the great powers.<br />

It is about protecting innocents from suffering.<br />

It is about providing people with the opportunity<br />

to reach reconciliation and rebuild their<br />

lives. It is about people.<br />

The longer the United Nations fails to live<br />

up to its potential, the longer we allow peacekeeping<br />

shortcomings to go unfixed, the longer<br />

the innocents will suffer, the greater the danger<br />

that we will be sucked in later – in a more costly<br />

way. I hope we will not turn away from the<br />

daunting tasks ahead of us at this particularly<br />

challenging moment.

AMERICAN ACADEMY<br />

NATASCHA VLAHOVIC<br />

H<br />

How Long was the Twentieth Century?<br />

ow will historians deal with the century that has<br />

just concluded? What narratives or interpretations will they<br />

construct to make sense of the last hundred years? Will the twentieth<br />

century cohere as a historical epoch? Twentieth-century history as<br />

such, I believe, will serve as a framework for what I call moral narratives<br />

but not as a chronological framework for thinking about politics and society.<br />

The problems it presents do not arise just because of ragged beginning<br />

and end points, such that 1914 and 1989 seem to open and close the political<br />

story, at least of Western history. Nor is the difficulty<br />

a result of the fact that internal caesuras, such<br />

as the defeat of fascism and the end of the world wars,<br />

might be viewed as so deeply dividing the Western<br />

narrative, at least, that the 1900s as a whole retain<br />

little»structural« unity. Rather, to focus on the twentieth<br />

century as such obscures the most encompassing<br />

Modern Times began around 1860 and fell apart in the late 1960’s<br />

By Charles S. Maier<br />

Charles S. Maier, Krupp Foundation Professor<br />

of European Studies and Director of the Center for<br />

European Studies at Harvard University, chairs the<br />

Berlin Prize committee of the American Academy in<br />

Berlin, where he delivered this paper in a seminar.<br />

12<br />

or fundamental sociopolitical trends of modern world development,<br />

these have followed a different trajectory through time, providing the territorially<br />

anchored structures for politics and economics that were taken<br />

for granted between 1860 and 1980, but have since begun to decompose.<br />

To focus on the twentieth century as a historical era obscures important<br />

developmental patterns that are better understood as products of a<br />

chronological period that began deep in the nineteenth century and then<br />

effectively concluded two to three decades before the century formally<br />

ended. As an argument about periodization, the<br />

thesis thus proposes that a cluster of developments<br />

I label territorialization and deterritorialization<br />

claim a degree of significance usually taken for<br />

granted. But, the twentieth century will not disappear<br />

as a historical reference point. Historians<br />

of the physical sciences, of music, of painting and

THE BERLIN JOURNAL<br />

a resource for governance; third co-opted the<br />

new leaders of finance and industry, science<br />

and professional attainment into a ruling cartel<br />

alongside the still powerful but no longer supreme<br />

representatives of the landed elite; and finally,<br />

they developed an industrial infrastructure<br />

based on the technologies of coal and iron as<br />

applied to long-distance transportation of goods<br />

and people, and the mass output of industrial<br />

products assembled by a factory labor force.<br />

Indeed, it was probably this technological tranarchitecture<br />

certainly use the label 20th-Century<br />

– validly so, given the fundamental innovations<br />

in all these fields between about 1905 and 1910.<br />

Perhaps most indelibly, the twentieth century<br />

has become synonomous with the narratives of<br />

moral atrocity that continue to transfix intellectuals<br />

and the public alike. For western intellectuals<br />

the twentieth century does not refer primarily<br />

to a chronological unit. Rather it constitutes<br />

a sort of moral epoch, a passage of time<br />

fundamentally characterized by war and viollence,<br />

i.e. by political killing, or, as Isaiah Berlin<br />

summarized it, as »the worst century there has<br />

ever been.«<br />

How Long Was<br />

the Nineteenth Century?<br />

This essay takes up, however, not the moral<br />

narrative of the twentieth century but the more<br />

structural theme of territoriality, which spills<br />

across the century’s chronological limits. When<br />

cited by historians, centuries are like Procrustes’<br />

famous bed: the Greek innkeeper either<br />

stretched his guests if they were too short or<br />

chopped them down if they were too long for<br />

the sleeping accommodations that were offered.<br />

By and large, historians of the West have<br />

stretched the 1800s into the »long nineteenth<br />

century,«extending it until WorldWar I.<br />

Europeanists, at least, have conceived of it as<br />

the century marked by industrial development,<br />

the triumph of the modern nation state, the advent<br />

of mass democracy, the partition of much<br />

of what would later come to be called the Third<br />

World, and finally by a superb confidence in economic<br />

and moral progress. As a pendant to this<br />

»long nineteenth century,« finally terminated<br />

by World War I, Eric Hobsbawm’s concept of a<br />

»short twentieth century« offers the advantage<br />

of accommodating the long nineteenth although<br />

it stops a decade ago in 1989. But European narratives<br />

serve less well the chronologies of African<br />

and Asian histories, whose caesuras have to do<br />

either with the impact of the West or indigenous<br />

developments that followed diverse rhythms.<br />

The twentieth century as such is not very useful,<br />

in fact, for understanding world historical<br />

development. I would propose instead that a<br />

coherent epoch of world development began in<br />

the sixth and seventh decades of the last century<br />

– say for the sake of simplicity around 1860 –<br />

and that its technological, cultural, and sociopolitical<br />

scaffolding began to corrode and fall<br />

apart in the late l960s, initiating a process of<br />

profound transformation in which we are still<br />

caught up.<br />

In a work that has fallen into undeserved oblivion,<br />

the historian Robert Binkley took account<br />

of this global transition sixty-five years ago in<br />

Realism and Nationalism, 1852-1871. Here he<br />

pointed out that political territories or national<br />

units had undergone a great crisis of confederal<br />

organization, abandoning – in a process of widespread<br />

civil wars – their traditional decentralized<br />

structures of politics for more administratively<br />

and territorially cohesive regimes. In the United<br />

States of the Civil War era; in Meiji Japan; in the<br />

German Confederation and the states of Italy; in<br />

the emerging halves of the Habsburg empire; in<br />

the British organization of India; in Canada,<br />

Mexico, Thailand, and later in the Ottoman empire;<br />

national societies were reforged in a rapid<br />

and often violent transformation; which first<br />

strengthened central government institutions<br />

at the expense of regional or confederal authority;<br />

second required that internal as well as external<br />

military capacity be continually mobilized as<br />

13<br />

NATASCHA VLAHOVIC<br />

sition that was responsible for the simultaneity<br />

of such geographically dispersed changes.<br />

What historians and political scientists have<br />

tended to take for granted until recently was<br />

that, common to all these national reorganizations,<br />

was an enhanced concept of territory as<br />

a source of national energy and power, administrative<br />

cohesion and economic resource. Not<br />

that historians have not dealt with frontiers,but<br />

they have done so primarily for the Roman Empire<br />

or in the context of the post-Westphalian,<br />

seventeenth-century state system, which secured<br />

the principle of sovereignty and renewed the<br />

preoccupation with fortified frontiers that had<br />

marked antiquity.<br />

Western statesmen and publics of the late<br />

nineteenth century believed that they must<br />

reinforce the frontiers anew. And not only geographical<br />

frontiers. Social and class upheaval at<br />

home as well as renewed international competition,<br />

compelled a renewed fixation on social<br />

enclosures of all sorts: boundaries that separated<br />

nation from nation, church from state, public<br />

from private, household from work, alleged<br />

male from reputed female roles.<br />

Modernity<br />

Came Through Energy<br />

But what further characterized mid-nineteenth<br />

century development was that, even as a<br />

new class of political leaders believed they must<br />

reestablish frontiers anew, they also emphasized<br />

that national power and efficiency rested on the<br />

saturation of space inside the frontier. The major<br />

concept was that of »energy.« National space<br />

was to be charged with »energy«, with prefectural<br />

presence, new railroads and infrastructure,<br />

mass-circulation newspapers, telegraphic communication<br />

and the possibilities of electrical<br />

power in general. The metaphors of contemporary<br />

physics provided a conceptual analogue. By<br />

the 1870s James Clerk Maxwell’s equations related<br />

electrical and magnetic fields and assigned<br />

every point in space a quantity of energy that<br />

emanated from the center. Territories, too, had<br />

a center: the national capital from which political<br />

and economic energy radiated outward. (In contrast,<br />

today’s metropolises are wired to each other,<br />

not their national hinterland, and conceived as<br />

suspendedinaworldnetworkofcapitalandlabor.)<br />

What were the resources of territoriality?<br />

First, quite simply, extent. Indeed, by the end<br />

of the century, territorial ambitions were extended<br />

to overseas empires, and geopolitical theorists<br />

divided over whether maritime or landed

AMERICAN ACADEMY<br />

extension offered more power. Population was<br />

obviously a resource and so, too, was economic<br />

development.<br />

I cite these developments because they<br />

proved fundamental to the collective organization<br />

of economics resources and political power<br />

for over a century – not the twentieth century,<br />

but rather the hundred or so years extending<br />

from the 1860s to the 1970s.<br />

The era of economic nationalism and protective<br />

tariffs starting in the l870s; the subsequent<br />

drive to annex overseas territory; the formation of<br />

long-term alliances during peace time, and the<br />

ratcheting up of the arms race that preceded the<br />

First World War; the ideological polarization<br />

between a Marxist Left and a militarist Right,<br />

thereafter between communism and fascism,<br />

and finally between Soviet power and its Atlantic<br />

alliance. These were the stages of historical development<br />

within this long era of territoriality.<br />

Identity Space and Decision Space<br />

Are No Longer Identical<br />

It is true that the Marxist Left sought to challenge<br />

the premises of territoriality and appeal<br />

to a revolutionary internationalism. Eventually,<br />

however, Communists achieved power only by<br />

accepting the premises of territorial power and<br />

development and building socialism within<br />

individual countries or by virtue of a new sort<br />

of imperial organization. Social Democrats<br />

emerged from their inter-war defeats convinced<br />

that the nation-state offered an appropriate fulcrum<br />

for democratic emancipation. They benefited<br />

from the fact that, by the 1940s, representatives<br />

of the industrial working class were co-opted<br />

into the power-sharing arrangements from<br />

which they had been largely excluded before.<br />

Common to all the changes that took place<br />

from the 1860s on, up through and beyond the<br />

admittedly important critical divides of 19l4<br />

and 1945, however, remained perhaps the fundamental<br />

premise of collective life, namely that<br />

what we can term »identity space« was coterminous<br />

with »decision space«; that is, that the<br />

territories to which ordinary men and women<br />

tended to ascribe their most meaningful public<br />

loyalties (indeed thus superseding competing<br />

supranational religious or social class affiliations)<br />

also provided the locus of resources for assuring<br />

their physical and economic security. This once<br />

familiar congruence no longer exists. Identity<br />

space and decision space are no longer seen as<br />

identical. Territoriality no longer suffices as a<br />

decisive resource; it is a problematic basis for<br />

collective political security and increasingly<br />

irrelevant to economic activity. Of course there<br />

are fierce exceptions where ethnic groups insist<br />

on hegemony. But renunciation of the Golan is<br />

probably more the sign of the times than claims<br />

for Kosovo.<br />

When and why did the territorial imperative<br />

loosen its grip? The coordinates of political and<br />

economic coordination created in the l860s<br />

began to dissolve in the l970s, a process that<br />

social scientists endeavored to grasp then as<br />

»interdependence,« and more recently as »globalization.«<br />

The processes that undermined the<br />

earlier epoch of territoriality were marked by<br />

a succession of world-wide crises beginning in<br />

the late l960s: the United States’ involvement<br />

in the Vietnam war and the protests it unleashed;<br />

the American unwillingness to continue<br />

upholding the international monetary regime;<br />

the emergence of new economic contenders<br />

whether through industrialization or the exploitation<br />

of their hold on world oil supplies; the<br />

breakdown of relatively easy collaborative industrial<br />

relations in Europe and the Americas; and<br />

shortly thereafter, the emergence of militant<br />

social movements among students, women<br />

and anti-nuclear protesters; and finally by the<br />

collapse of state socialism and planned economies<br />

during the 1980s, systems even more vulnerable<br />

to the seismic changes underway than the<br />

market economies that enjoyed a renewed vigor<br />

on a post-territorial and post-Fordist basis.<br />

14<br />

NATASCHA VLAHOVIC<br />

Indeed, the collapse of communist regimes<br />

in 1989-90 and the end of the Cold War rivalry<br />

can be seen as the most spectacular political<br />

consequence of the weakening of territorial<br />

politics. It had been the state socialist regimes,<br />

after all, that were most committed to controlling<br />

politics, economics and ideology on the<br />

basis of territory and frontiers (most tangibly<br />

in East Germany), and also most heavily invested<br />

in the aging processes of heavy industry that<br />

had characterized the territorial era.<br />

For just as a qualitative change of technological<br />

possibilities for mastering space and its extension<br />

had facilitated the political transformations<br />

of the century after 1860, so the very technological<br />

transformations of the last thirty years have<br />

tended to make physical space a less relevant<br />

resource. The age of coal and iron, and then, too,<br />

of hydrocarbon chemistry, of oil and electricity,<br />

of aluminum and copper as well as steel – all<br />

still epitomized even in the l950s and l960s –<br />

was overlaid in fact, and in the public imagination<br />

– by the technologies of semiconductors,<br />

computers, and data transmission – with a<br />

new accepted basis for creating private wealth.<br />

The concept of hierarchically organized Fordist<br />

production (based on a national territory) was<br />

supplanted by the imagery, if not always the<br />

reality, of globally co-ordinated networks of information,<br />

mobile capital, and migratory labor.<br />

Our Fin-de-siecle<br />

came sometime after 1968<br />

The political result has been to transform<br />

the major political division of our times. This<br />

separates those who envisage their future prospects<br />

based on non-territorial markets or<br />

exchange of ideas, and those who insist that territoriality<br />

can be reinvigorated as the basis for<br />

economic and political security – whether on<br />

the basis of provincial regionalism, or supranational<br />

organization, or by harsher measures of<br />

ethnic homogeneity or territorially and religiously<br />