Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Making a Difference<br />

Livia Bitton-Jackson’s Story of Survival<br />

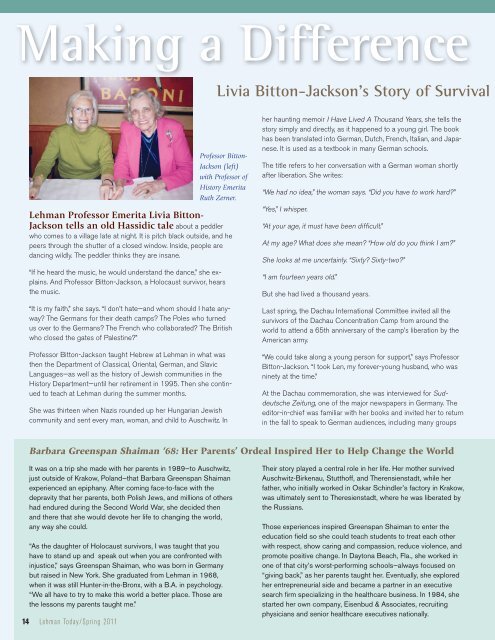

Professor Bitton-<br />

Jackson (left)<br />

with Professor of<br />

History Emerita<br />

Ruth Zerner.<br />

<strong>Lehman</strong> Professor Emerita Livia Bitton-<br />

Jackson tells an old Hassidic tale about a peddler<br />

who comes to a village late at night. It is pitch black outside, and he<br />

peers through the shutter of a closed window. Inside, people are<br />

dancing wildly. The peddler thinks they are insane.<br />

“If he heard the music, he would understand the dance,” she explains.<br />

And Professor Bitton-Jackson, a Holocaust survivor, hears<br />

the music.<br />

“It is my faith,” she says. “I don’t hate—and whom should I hate anyway?<br />

The Germans for their death camps? The Poles who turned<br />

us over to the Germans? The French who collaborated? The British<br />

who closed the gates of Palestine?”<br />

Professor Bitton-Jackson taught Hebrew at <strong>Lehman</strong> in what was<br />

then the Department of Classical, Oriental, German, and Slavic<br />

Languages—as well as the history of Jewish communities in the<br />

History Department—until her retirement in 1995. Then she continued<br />

to teach at <strong>Lehman</strong> during the summer months.<br />

She was thirteen when Nazis rounded up her Hungarian Jewish<br />

community and sent every man, woman, and child to Auschwitz. In<br />

her haunting memoir I Have Lived A Thousand Years, she tells the<br />

story simply and directly, as it happened to a young girl. The book<br />

has been translated into German, Dutch, French, Italian, and Japanese.<br />

It is used as a textbook in many German schools.<br />

The title refers to her conversation with a German woman shortly<br />

after liberation. She writes:<br />

“We had no idea,” the woman says. “Did you have to work hard?”<br />

“Yes,” I whisper.<br />

“At your age, it must have been difficult.”<br />

At my age? What does she mean? “How old do you think I am?”<br />

She looks at me uncertainly. “Sixty? Sixty-two?”<br />

“I am fourteen years old.”<br />

But she had lived a thousand years.<br />

Last spring, the Dachau International Committee invited all the<br />

survivors of the Dachau Concentration Camp from around the<br />

world to attend a 65th anniversary of the camp’s liberation by the<br />

American army.<br />

“We could take along a young person for support,” says Professor<br />

Bitton-Jackson. “I took Len, my forever-young husband, who was<br />

ninety at the time.”<br />

At the Dachau commemoration, she was interviewed for Suddeutsche<br />

Zeitung, one of the major newspapers in Germany. The<br />

editor-in-chief was familiar with her books and invited her to return<br />

in the fall to speak to German audiences, including many groups<br />

Barbara Greenspan Shaiman ‘68: Her Parents’ Ordeal Inspired Her to Help Change the World<br />

It was on a trip she made with her parents in 1989—to Auschwitz,<br />

just outside of Krakow, Poland—that Barbara Greenspan Shaiman<br />

experienced an epiphany. After coming face-to-face with the<br />

depravity that her parents, both Polish Jews, and millions of others<br />

had endured during the Second World War, she decided then<br />

and there that she would devote her life to changing the world,<br />

any way she could.<br />

“As the daughter of Holocaust survivors, I was taught that you<br />

have to stand up and speak out when you are confronted with<br />

injustice,” says Greenspan Shaiman, who was born in Germany<br />

but raised in New York. She graduated from <strong>Lehman</strong> in 1968,<br />

when it was still Hunter-in-the-Bronx, with a B.A. in psychology.<br />

“We all have to try to make this world a better place. Those are<br />

the lessons my parents taught me.”<br />

14 <strong>Lehman</strong> Today/<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>2011</strong><br />

Their story played a central role in her life. Her mother survived<br />

Auschwitz-Birkenau, Stutthoff, and Therensienstadt, while her<br />

father, who initially worked in Oskar Schindler’s factory in Krakow,<br />

was ultimately sent to Theresienstadt, where he was liberated by<br />

the Russians.<br />

Those experiences inspired Greenspan Shaiman to enter the<br />

education fi eld so she could teach students to treat each other<br />

with respect, show caring and compassion, reduce violence, and<br />

promote positive change. In Daytona Beach, Fla., she worked in<br />

one of that city’s worst-performing schools—always focused on<br />

“giving back,” as her parents taught her. Eventually, she explored<br />

her entrepreneurial side and became a partner in an executive<br />

search fi rm specializing in the healthcare business. In 1984, she<br />

started her own company, Eisenbud & Associates, recruiting<br />

physicians and senior healthcare executives nationally.