10-29-2012-RomanPres-7-Roman-Merchant-Ships - Emmaf.org

10-29-2012-RomanPres-7-Roman-Merchant-Ships - Emmaf.org

10-29-2012-RomanPres-7-Roman-Merchant-Ships - Emmaf.org

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

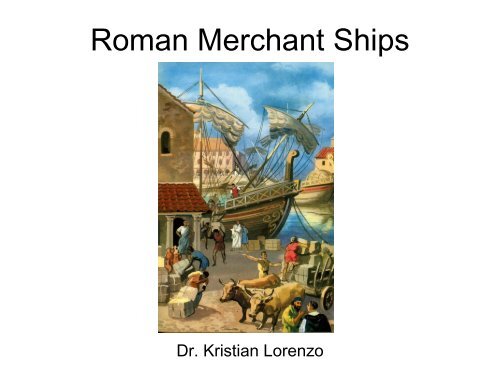

<strong>Roman</strong> <strong>Merchant</strong> <strong>Ships</strong><br />

Dr. Kristian Lorenzo

<strong>Roman</strong> <strong>Merchant</strong> <strong>Ships</strong>: Today’s Topics<br />

<strong>Roman</strong> Aristocratic Attitudes towards Trade<br />

Monte Testaccio<br />

<strong>Merchant</strong> Ship Design vs. Warship Design<br />

The Madrague de Giens Wreck<br />

The Commachio Wreck<br />

The Torre Sgarrata Wreck<br />

Why study <strong>Roman</strong> <strong>Merchant</strong> wrecks?

<strong>Roman</strong> Attitudes Toward Trade<br />

The <strong>Roman</strong> aristocracy on the whole maintained a distance from direct<br />

involvement in trade, however…<br />

They could benefit from the profits of trade through intermediaries. For example<br />

an aristocrat’s freedmen could manage their former owner’s investments in<br />

potteries, mines, textile production, oil, wine, grain, etc.<br />

Even people such as Cato the Elder (234-149 BC), despite his conservative<br />

attitudes, began to invest in overseas trade. He went as far as investing in<br />

speculative trading ventures by purchasing small shares in large mercantile<br />

consortia thereby spreading the risk.

Cato the Elder, 123-49 BC<br />

“He used to loan money out in the most disreputable of all ways, namely<br />

in shipping, and according to the following formula. He required his<br />

borrowers to form a large company, and when there were fifty partners<br />

and as many ships for his security, he invested in one share of the<br />

company. He event sent his freedman, Quintio, along on all their<br />

ventures. In this way his entire security was not imperilled, but only a<br />

small part of it, and his profits were large.”<br />

Plutarch (Cat. Mai. 21.6)

Monte Testaccio<br />

An artificial mound ca. 118 ft. tall and covering roughly 66,000 sq. ft. of<br />

pottery sherds in Rome created by centuries of discarded, broken amphorae.

Monte Testaccio<br />

Laid down from the 1 st to the mid-3 rd centuries AD, and mostly composed of oil<br />

amphorae from Spain with a smaller amount from North Africa and evidence for<br />

an estimated oil trade in the city of ca. 50,600,000 lbs

Monte Testaccio<br />

Laid down from the 1 st to the mid-3 rd centuries AD, and mostly composed of oil<br />

amphorae from Spain with a smaller amount from North Africa and evidence for<br />

an estimated oil trade in the city of ca. 50,600,000 lbs

<strong>Roman</strong> <strong>Merchant</strong> <strong>Ships</strong> vs. Warships<br />

<strong>Merchant</strong> ship designs are relatively<br />

invariable like cargo boxes.<br />

Warship designs are very variable<br />

depending on the weaponry, fighting<br />

force, and method of propulsion.

<strong>Roman</strong> <strong>Merchant</strong> <strong>Ships</strong><br />

Cargo ships are built heavily (or sturdily) with a normal length to beam of 1:3<br />

(i.e. short and stocky)

<strong>Roman</strong> Warships<br />

A <strong>Roman</strong> Trireme<br />

Warships are built lightly with a normal length to beam ratio of 1:5 or 1:6 (i.e. long<br />

and skinny)

<strong>Roman</strong> <strong>Merchant</strong> Ship: the Madrague de<br />

Giens wreck<br />

Discovered in 1967 of the<br />

sounthern coast of France<br />

near the little fishing port of<br />

La Madrague de Giens<br />

some 30 km. east of Toulon<br />

Excavated from 1972-1982<br />

at depth of ca. 54-60 ft.<br />

300-400 ton ship over 120<br />

ft. long and 27 ft. wide and<br />

with a hull depth of 13.5 ft.<br />

One of the largest ancient<br />

wrecks ever found

The Madrague de Giens wreck<br />

The cargo included about 6,000 to 6,500 wine amphora, all of Dressel Type 1B,<br />

which were stacked in 3 layers, 9 ft. high

The Madrague de Giens wreck: Dressel Type IB<br />

Key: 1 – rim; 2 – neck; 3 – handle; 4 – shoulder; 5 – belly or body; 6 – toe.

The Madrague de Giens wreck: Dressel Type IB<br />

Many of the amphorae displayed potters stamps, the most frequent one was Publius<br />

Veveius Papus, which allows the origin of the amphora to the traced to Terracina,<br />

Italy.

Amphorae Stamps from the Villa of the Laecanius family<br />

Located on the coast of Croatia at Fazana and Brijuni the Laecanii had villas with at<br />

least one workshop producing amphorae for oil.

Amphorae Stamps from the Villa of the Laecanius family<br />

Each amphora was stamped twice both on the rim, Laecanius’s at the center and the<br />

estate manager’s above one of the handles

The Madrague de Giens wreck<br />

A secondary cargo of black glazed pottery was placed in boxes above the amphora,<br />

perhaps as a space filler?

The Madrague de Giens wreck: the Hull<br />

A large section of the hull was preserved by being sandwiched between the layers<br />

of amphorae and the sea bed and then buried my sediment, dead marine life, etc.

The Madrague de Giens wreck<br />

Some of the wreck’s cargo in situ during excavation.

The Madrague de Giens wreck: Urinatores<br />

The wreck also provided evidence that professional urinatores had attempted to<br />

salvage some of the cargo.

The Madrague de Giens wreck: Ballast Stone<br />

The evidence for this were ballast stones that were found throughout the cargo -<br />

geological analysis showed that the stones came from the local coast (not shown).

The Madrague de Giens wreck: Urinatores<br />

The urinatores used the stones to help them reach the seabed where they could<br />

recover parts of the cargo. It is estimated that they managed to recover about<br />

half of the amphorae, together with the ship’s anchors and various other pieces<br />

of equipment, including the bilge pump.

A Local Trading Vessel: The Comacchio Wreck<br />

Discovered in 1980, on the outskirts of<br />

Comacchio, Italy on the Adriatic coast<br />

south of Venice<br />

Excavated from 1986-1989<br />

Dated to ca. 12 BC, by dendrochronology<br />

Ca. 60 ft. of the hull preserved<br />

Beached near a river mouth during a<br />

storm with all its cargo

The Comacchio Wreck: The Cargo<br />

The primary cargo were <strong>10</strong>2 lead ingots of Spanish origin, amphorae for food<br />

transport and boxwood logs. An ingot is a specific quantity of metal cast in a<br />

form convenient for shaping, re-melting or refining.

The Comacchio Wreck: The Cargo<br />

North Italic sigillata pottery was also found on board as well as a bronze balance<br />

with which to sell merchandise by retail probably along a small local route in the<br />

region of the Po valley

The Comacchio Wreck: Importance<br />

The variety and rarity of the materials transported by the vessel make this one<br />

of the most significant discoveries ever made in the Ferrara delta. They reflect<br />

the complexity and liveliness of commercial contacts which were redistributed<br />

along the Po River in the late 1 st century BC.

A Marble Transport: the Torre Sgarrata<br />

Shipwreck<br />

Excavated in 1967 in<br />

the Gulf of Taranto, i.e.<br />

Italy’s instep<br />

Coins from the reign of<br />

Commodus, indicate<br />

the ship sank after AD<br />

192<br />

Sank in shallow water,<br />

ca. 30 ft. deep

A Marble Transport: the Torre Sgarrata Shipwreck<br />

The ship was loaded with almost 170 tonnes of rough-cut marble from Asia Minor,<br />

which included 18 sarcophagi, 23 blocks of stone (six of which were alabaster) and<br />

a huge column. There was also thin sheets of marble veneer.

A Marble Transport: the Torre Sgarrata Shipwreck<br />

An unfinished garland sarcophagus from Ephesos in Turkey.

A Marble Transport: the Torre Sgarrata Shipwreck<br />

An almost finished garland sarcophagus from the so-called Licinian tomb in<br />

Rome, ca. AD 150-180. It is made of Dokimeion marble from Turkey.

A Marble Transport: the Torre Sgarrata Shipwreck<br />

One of the ship’s iron anchors was also found and raised with the help of balloon lifts.

A Marble Transport: the Torre Sgarrata Shipwreck<br />

One of the maritime archaeologist’s recording the dimensions of the ship’s iron anchor.

Why Study <strong>Roman</strong> <strong>Merchant</strong> Wrecks?<br />

Yields important data about trade routes<br />

Types of shipped items: oil, grain, olives, stone, ingots, pottery, etc.<br />

The scale of trade, the size of boats and their carrying capacity<br />

Yields important data about local trade

Why Study <strong>Roman</strong> <strong>Merchant</strong> Wrecks?<br />

Yields Important data about international trade<br />

The stamps on certain artifacts can be studied to determine who<br />

produced the product and where it was produced, so<br />

prosopographical* info and region specific economic data<br />

Steps of production i.e. unfinished to finished sarcophagi and other<br />

stone artifacts such as column drums also treated in the same way<br />

*Prosopography – the study of persons or characters, especially their<br />

appearances, careers, personalities, etc., within a historical, literary, or<br />

social context.