Gettysburg and Silence - Chantrill.net

Gettysburg and Silence - Chantrill.net

Gettysburg and Silence - Chantrill.net

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

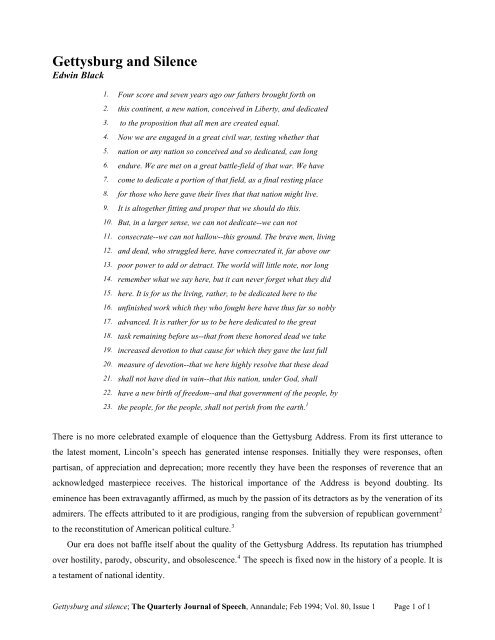

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Silence</strong><br />

Edwin Black<br />

1. Four score <strong>and</strong> seven years ago our fathers brought forth on<br />

2. this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, <strong>and</strong> dedicated<br />

3. to the proposition that all men are created equal.<br />

4. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that<br />

5. nation or any nation so conceived <strong>and</strong> so dedicated, can long<br />

6. endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have<br />

7. come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place<br />

8. for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live.<br />

9. It is altogether fitting <strong>and</strong> proper that we should do this.<br />

10. But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate--we can not<br />

11. consecrate--we can not hallow--this ground. The brave men, living<br />

12. <strong>and</strong> dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our<br />

13. poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long<br />

14. remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did<br />

15. here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the<br />

16. unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly<br />

17. advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great<br />

18. task remaining before us--that from these honored dead we take<br />

19. increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full<br />

20. measure of devotion--that we here highly resolve that these dead<br />

21. shall not have died in vain--that this nation, under God, shall<br />

22. have a new birth of freedom--<strong>and</strong> that government of the people, by<br />

23. the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth. 1<br />

There is no more celebrated example of eloquence than the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address. From its first utterance to<br />

the latest moment, Lincoln’s speech has generated intense responses. Initially they were responses, often<br />

partisan, of appreciation <strong>and</strong> deprecation; more recently they have been the responses of reverence that an<br />

acknowledged masterpiece receives. The historical importance of the Address is beyond doubting. Its<br />

eminence has been extravagantly affirmed, as much by the passion of its detractors as by the veneration of its<br />

admirers. The effects attributed to it are prodigious, ranging from the subversion of republican government 2<br />

to the reconstitution of American political culture. 3<br />

Our era does not baffle itself about the quality of the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address. Its reputation has triumphed<br />

over hostility, parody, obscurity, <strong>and</strong> obsolescence. 4 The speech is fixed now in the history of a people. It is<br />

a testament of national identity.<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 1 of 1

The <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address has been, from its genesis, an aesthetic object. Its career has recapitulated that of<br />

many another exalted work of art, a career that begins, invisibly, as an amorphy of inchoate ideas within the<br />

mind of an author. Those mental fragments, combined <strong>and</strong> recombined under the impulse of aspiration, are<br />

subjected to an impe<strong>net</strong>rable process of discrimination <strong>and</strong> refinement by the author, who finally forms them<br />

into an autonomous creation. That product somehow takes hold; it endures; it survives controversy <strong>and</strong> the<br />

vicissitudes of fashion; in time it achieves, as the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address has, an iconic status: the artifact has<br />

transcended the condition of being evaluated by having become an exemplary definition of value itself. Its<br />

entry into that pantheon is signaled when it begins to elicit a set of critical questions reserved only for<br />

paradigmatic works: questions no longer about how it should be judged; but rather, questions about how it<br />

has shaped the culture to which it has become sacred, what the sources are of its influence, what the secrets<br />

are of its enchantments. The masterpiece becomes to the critic what the mountain is to the climber.<br />

Its reputation now established as a touchstone of public discourse, the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address is a subject<br />

that tests criticism more than it is tested by criticism. If the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address were a simple composition, it<br />

would long ago have depleted its own interpretive possibilities. 5 But the Address can probably not be<br />

exhausted by any single examination, <strong>and</strong> certainly not by any monistic one. Despite the inescapable<br />

temporality of its medium, it eludes even line-by-line or word-by-word analysis. The speech is at once too<br />

compressed <strong>and</strong> too intricate. It is so brief that its first portentous words are still held in the mind even as its<br />

last syllables are being comprehended. And yet, each element of the Address is so tightly implicated in other<br />

elements that its cumulative effect is but one of its multifarious effects. Its duration is an infrangible unity.<br />

The Address is prismatic. Its aspects reflect back <strong>and</strong> forth on one another such radiant multiplicity that,<br />

diamond-like, its fires are somehow both protean <strong>and</strong> integral. The complexity of the Address, which has<br />

been requisite to its ascendance, enables it to give back a singular answer to each critic who brings to it the<br />

question, how does it work? One mark of a masterpiece may be its critical inexhaustibility; its capacity to<br />

accommodate the diverse partialities of its observers, <strong>and</strong> yet to abide in its integrity. And the uniquely<br />

prismatic character of the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address brings it to reflect, with uncommon brilliance, any light that is<br />

thrown on it, however dim.<br />

How does one examine a prism? By looking at it through one facet after another, in no particular order.<br />

That will be the method here. It is a method without system <strong>and</strong> therefore scarcely a method at all, at least<br />

not a predetermined one. But times--maybe even all the time--a subject deserves to supersede a method, <strong>and</strong><br />

to receive its own forms of disclosure.<br />

How does the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address function rhetorically? The answer is in the details.<br />

AUDIENCES<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 2 of 2

The first paragraph of the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address seems addressed to the ages. Lincoln does not imply a<br />

particular audience. He speaks the voice of omniscience, articulating a historical narrative with incontestable<br />

certitude. The first paragraph is a description of national genesis. It is a purposeful creation, an initiating<br />

fusion of origin <strong>and</strong> essence: the generation not only of an entity, but also of a mission. That genesis <strong>and</strong><br />

meaning stipulates the frame of the speech. Anyone who deny, doubt, or qualify the narrative is implicitly<br />

excluded from Lincoln’s audience. By announcing a major premise, the form of the first sentence signals<br />

that a deductive procedure has been started, <strong>and</strong> that the procedure will be according self-contained. The<br />

choice left the auditor is single: to be or not to be an auditor to this speech.<br />

The narrative of national creation is austere, its only concession to embellishment being the natal<br />

metaphor, but even that metaphor is so fundamental that the metaphor itself is almost dead. The moribundity<br />

of the metaphor prevents its being experienced as an embellishment; its inconspicuousness as a stylistic<br />

decoration is compatible with the spartan character of the first paragraph. That quality of barrenness in the<br />

style of the first paragraph is characteristic of the enunciation of first principles. (“In the beginning God<br />

created the heavens <strong>and</strong> the earth.”) No gratuities must be attached to an account that m<strong>and</strong>ates unqualified<br />

commitment. The articulation of an absolute belief requires the exactitude of purity. The first paragraph’s<br />

narrative is advanced as absolute truth, <strong>and</strong> so it has no specifiable audience. It constitutes the initial<br />

statement of the facts of the case, the undisputed <strong>and</strong> undisputable ground for any judgment that may be<br />

issued by the rhetor or formed by an auditor.<br />

The second paragraph subsumes the war, the battlefield, <strong>and</strong> the ceremony to the synoptic historical<br />

narrative. The civil war is linked to the nation’s beginning by being a test of its founding principle (4-6). And<br />

the ceremony is linked to the civil war by its location <strong>and</strong> its purpose (6-9). In anticipation of the Address’s<br />

later reinterpretation of the occasion’s purpose, the paragraph ends with an assurance that its conventionally<br />

understood rationale is an appropriate product of historical circumstance: “It is altogether fitting <strong>and</strong> proper<br />

that we should do this.”<br />

“But” (10) begins a decisive shift in perspective. The “larger sense” (10) that will now inform the<br />

discourse is a sense no longer merely of appropriateness, but, more encompassing, of moral adequacy. “But”<br />

also crystallizes a shift of the object of the Address to the audience at <strong>Gettysburg</strong>. The immediate audience<br />

had been discussed (6-9) only in its relation to the larger historical account. Beginning with “but,” its<br />

capacities <strong>and</strong> obligations occupy the speech. The focus remains arrested on the cemetery at <strong>Gettysburg</strong> for<br />

awhile, reinforced by six references to “here”--six references in five lines (12, 14, 15, 16, 17).<br />

The word “here” tolls like a bell through that period of fixation on the present moment. It appears a total<br />

of eight times in the speech. Two functions, at least, can be attributed to the repetition of “here,” in addition<br />

to the enhancement of the rhythmic solemnity of the Address. One is the pointing these repetitions do of the<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 3 of 3

occasion: their constituting a recurrent anchor for one moiety of a bipolar orientation in which the implicit<br />

“there,” which contrasts with “here,” is the future. During the section of the speech when the audience’s<br />

attention is fastened to the occasion, “here” serves to remind them not only of that occasion, but also of how<br />

bounded the occasion is, <strong>and</strong> of the co-existence with the “here” of a “there”: a different <strong>and</strong> less bounded<br />

time <strong>and</strong> place. “Here” is a particular location amidst infinity. “Here” is a particular moment during eternity.<br />

The other function of the repetition of “here” —a subtler function—relates to the pun on “hear,” a recurrent<br />

comm<strong>and</strong> issued to the audience to attend. Faintly, allophonically, Lincoln directs his audience to listen.<br />

The first-person plural references during the middle of the speech (6-14) all have the audience at<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> at their center. With the instruction to “us the living” (15), however, the synecdochal character of<br />

the first-person plural begins reemerging to a point of unmistakable clarity (21) that “we” st<strong>and</strong> in deputy to<br />

the whole nation <strong>and</strong> act on its behalf. The audience, then, transcribes a movement through the speech from<br />

unspecified universal (1-3) to national (4) to local (6-14), back to national again.<br />

THE MOVEMENT OF THE ADDRESS<br />

A consideration of the implied audience brought us to observe that the word “But” in line 10 confirms a shift<br />

of perspective from the historical to the moral, <strong>and</strong> of object from a general to a more specific audience. This<br />

shift constitutes a hesitation: an arrest of time <strong>and</strong> place in the middle of the speech, a riveting on the present.<br />

The speech is so compressed that even that fixation passes too quickly to effect any sense of intellectual<br />

paralysis. The arrest is, rather, a short-lived entrancement, an instant in which the options are inventoried for<br />

the future of a moment whose past has been ascertained. What has led us to this moment is the subject of the<br />

speech from its beginning to “But.”<br />

“But” begins a process of rejection. The first two paragraphs of the Address constitute a historical setting<br />

of the occasion, <strong>and</strong> a normal extrapolation from the pronouncements of those paragraphs would lead toward<br />

performative utterance. Our past has led us to the point of declaring this burial ground sacred; but yet, we<br />

demur. Why? Because we have neither the right nor the duty. A moral intervention prevents the fulfillment<br />

of conventional form; a customary itinerary has been deflected. Our right has been superseded by those who<br />

have died. Our duty lies elsewhere: it is to take up the task left unfinished by the dead. The speech links us to<br />

the dead by virtue of the common task, <strong>and</strong> by the bond of our obligation to complete what they have left<br />

incomplete.<br />

If we think of the movement of the Address in terms of what Berenson has called “respirational values,”<br />

we can appreciate that the speech is temporarily arrested at the point of maximum contraction. 6 The<br />

narrowing of location from continent (2) to nation (2) to battle-field (6) to portion of that field (7) to resting<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 4 of 4

place (7) finally pivots with “But” even to a rejection of our capacity to affect “this ground” (11). Then, in<br />

line 15, a movement recommences, <strong>and</strong> an expansion continues to the end.<br />

The second “rather” (17) is the second pivot of the speech. It decisively turns from the focus on the<br />

present <strong>and</strong> commences the movement into the future. The first “rather” (15) prepares for that pivot by<br />

shifting the subject from the dead to the living. It signals a throwing off of the immobility that restrains the<br />

middle of the speech; it is a bestirring, a resumption. With the second “rather,” the movement recommences,<br />

with its temporal <strong>and</strong> spatial directions clearly manifested.<br />

The “new birth of freedom” (22) echoes “our forefathers brought forth” (1). An implicit contrast<br />

sponsored by the speech is not just between living <strong>and</strong> dying; it is also between birthing <strong>and</strong> dying: a subtle<br />

distinction, perhaps, but crucial to the character of the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address. That latter contrast enables<br />

Lincoln to subordinate the living (13-14, 15-18) to the task of political renascence (22).<br />

The “brave men” (11) who “gave the last full measure of devotion” (19-20) have died, but in the end, it<br />

is a form of government that “shall not perish from the earth.” They “gave their lives that that nation may<br />

live” (8). There are two forms of life, then: the life of the nation, which must endure, <strong>and</strong> the lives of the<br />

fallen soldiers, who died in order that the nation may continue living.<br />

GEOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES<br />

The references to place have the same pattern of progressive confinement followed by progressive<br />

enlargement as does the implied audience. First, continent (2), followed quickly by nation (2). Nation is<br />

reiterated twice more (5). Then, a process of narrowing proceeds: battle-field (6), then portion of that field<br />

(7), then resting place (7). There follows a reference to nation (8), but nation there is not place; it is organism<br />

(“that that nation might live”). “This ground” (11) is a slight loosening of the geographical constriction,<br />

preliminary to an expansionary movement, which goes to “world” (13)—but not altogether a place either,<br />

since it has memory. Then “nation” (21), but having a birth, <strong>and</strong> so still an organism. And finally, the<br />

location of all knowable places: “the earth” (23). The designations of place, then, first proceed from<br />

“continent” to diminishing measures of location, to the nadir, “resting place.” Then the direction of<br />

movement is reversed, <strong>and</strong> it proceeds toward increasingly enlarged measures, to the apogee, “the earth.”<br />

The movement of spatial allusions is one of contraction followed by expansion.<br />

The geographical references juxtapose animate with inanimate associations. The movement begins<br />

with an inanimate “continent,” but moves quickly to the inanimate “nation,” iterated three times. Then,<br />

inanimate references, three again, to battle-field, portion of field, <strong>and</strong> final resting place.<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 5 of 5

All five allusions to “nation” (2, 5, 8, 21) in the speech are in the same form, so that “nation,” while<br />

animate, is stable. But the inanimate geographical references continuously alter in focus· The variety of<br />

allusions to the site—“battle-field,” “portion of that field,” “resting place,” <strong>and</strong> “here” eight times--are<br />

variations in perspective, while the perspective on “the nation” is held constant. Moreover, the allusions to<br />

the site are uniformly inanimate--they allude simply to a place, but a place whose consecration is the issue<br />

presented by the speech. However, the references to other places—“nation” five times, <strong>and</strong> the world used<br />

synecdochically—are all animate, excepting only the ambiguous final reference to “the earth.”<br />

The speech presents two implicit <strong>and</strong> repeatedly reinforced geographical contrasts. One is the contrast<br />

between the site of <strong>Gettysburg</strong>, which is a consecrated place where lives were given, <strong>and</strong> “the nation,” which<br />

has been endowed with life from the first sentence. The second is between “the nation,” which is treated as a<br />

fixed conception in the speech, <strong>and</strong> all the other geographical references, which vary in size, location <strong>and</strong><br />

function. Here we have one of the many ironies of the Address. While we would ordinarily associate<br />

stability--the cessation of change--with entropy <strong>and</strong> death, Lincoln sustains constancy in his animate<br />

conception of “the nation,” <strong>and</strong> diversifies his other geographical references, which are inanimate. A<br />

consequence is that “nation,” which is ostensibly a geographical term employed along with other<br />

geographical terms, is singularly endowed with the values of duration <strong>and</strong> viability.<br />

Finally, the earth. The cemetery at <strong>Gettysburg</strong> is a place where the earth receives the dead· Lincoln’s<br />

immediate audience would have had an active awareness of that fact, <strong>and</strong> even their successors are reminded<br />

by the speech of its setting (4-8). The earth, then, <strong>and</strong> all of its synecdochal variants—field, resting place,<br />

ground—is a continuously active referent in the web of meaning. And at the very end of the Address, where<br />

Lincoln specifies the earth as the place where the principle of the living nation will continue its life, he<br />

abruptly—with his last word—inverts a signification that preceded the speech in the minds of the auditors,<br />

<strong>and</strong> that the speech had been careful to maintain. In an instant, the resting place of the dead becomes the<br />

habitation of a vital principle, renascent <strong>and</strong> imperishable. The unity of the dead with the living is<br />

consummated in Lincoln’s last word, the common home of all.<br />

STRUCTURE<br />

The structural elegance of the discourse can be rendered statistically. The speech consists of 367 syllables. Its<br />

first pivot occurs at syllable 146; its second pivot at syllable 263. One-third through the syllables is at 122;<br />

two-thirds through at 244. The speech consists of 272 words. The first pivot is at word 103; the second pivot<br />

at word 193. One-third through the words is at 91; two-thirds at 182.<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 6 of 6

The two major pivots in the speech are spaced with amazing precision. If the first word of the speech is<br />

given a value of 1, <strong>and</strong> the last word a value of 100, the first pivot occurs at word 37.8 (syllable 39.7); the<br />

second pivot at word 70.9 (syllable 71.6). If 33.3 <strong>and</strong> 66.6 represent a mathematical perfection of placement<br />

in each of the two cases, it is clear that Lincoln came remarkably close to such precision, considering that<br />

this was a speech <strong>and</strong> not a mathematical exercise. He is only twelve words off mathematical perfection in<br />

the first pivot <strong>and</strong> nine words off it in the second.<br />

If the speech is divided into twenty-three lines (as it is on my computer): nine lines constitute the<br />

statement of facts; then five lines constitute the pause; then nine lines constitute the resolution. The<br />

mathematical proportioning of the speech is so close to perfect that it seems almost formulary, yet it is<br />

inconceivable that it actually was. The two sections of movement are equal in length; the middle section of<br />

arrest is virtually half the length of either of the sections of the movement.<br />

In visual terms, the speech is shaped like an hourglass. Temporally, it is past, present, then future. Its<br />

visceral effects are contraction, strain, <strong>and</strong> then release. Respirationally, it is an exhalation, then a pause, then<br />

an inhalation.<br />

The structure of the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address imposes a corresponding form on the experience of its auditor.<br />

That experience is composed of initial tension, followed by tightening, followed by progressive exhilaration.<br />

The opening sentence concentrates the attention of the auditor <strong>and</strong> contributes to the auditor’s tension. In its<br />

effect, that sentence disciplines the auditor’s response. The first sentence is a comm<strong>and</strong> to be reverential, a<br />

comm<strong>and</strong> yielded by the archaic solemnity of the sentence <strong>and</strong> by the august historical perspective that it<br />

announces. The comm<strong>and</strong> is reinforced by the inherent gravity of the occasion <strong>and</strong> by the high office of the<br />

speaker. The tension is sustained through the narrative that brings the historical account to the moment of the<br />

ceremony (4-8).<br />

There is a brief, soothing reassurance (9), a promise that the contained energy of reverence will be<br />

discharged in an appropriate ceremony. But then, at that acme of expectation <strong>and</strong> vulnerability, the auditor’s<br />

strain is suddenly intensified by the ostensible denial that the ceremony itself could be efficacious (10-15). It<br />

is a repudiation that dislocates the reverence that had been initially sponsored by the speech. And that<br />

concussion of form is followed by yet another reversal: At the most potentially explosive point in the<br />

stressing of the auditor, a controlled release of the auditor’s tension begins (15). The medium of that release<br />

is the prescription for the continuing task of self-dedication by which the audience can be constructively<br />

absorbed <strong>and</strong> into which its reverence can be invested (15-23).<br />

In lines 10-20, we have a series of contrasts, first between us <strong>and</strong> “the brave men, living <strong>and</strong> dead, who<br />

struggled here,” <strong>and</strong> then, via the reference to “us the living” (15), between us <strong>and</strong> the dead: We cannot<br />

consecrate; they have consecrated. We say here; they did here. We have unfinished work; they nobly<br />

advanced work. We take devotion; they gave devotion. In each of these contrasts, we are passive <strong>and</strong><br />

receptive; they who struggled are active <strong>and</strong> productive. Throughout these contrasts, our passivity is inferior<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 7 of 7

to their activity. But at last we are given an activity (15-23) which can assuage the appetite that the contrasts<br />

have aroused: an appetite for moral equilibrium. This treatment of contrasts too is a pattern of strain followed<br />

by release.<br />

There is not an instant in the course of the speech when the experience of the audience is not subjected to<br />

its controlling configuration of tension <strong>and</strong> resolution. We are coiled by the Address, <strong>and</strong> then sprung. The<br />

structure of the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address is an organization of the auditor’s energy.<br />

SCOPE OF THE ADDRESS<br />

The Address has an oracular quality. The voice that speaks is not, at first hearing, an individual voice: it<br />

betrays no particular perspective. The speech abounds in first-references, but none is singular. 7 The fifteen<br />

first-person, plural references are concessions to the ceremony that has prompted the Address.<br />

The speech sustains distance from the dedicatory event; it hovers above the event, commenting on it in<br />

relation to history. Beginning with the founding of the Republic, the focus goes first to the war, then to the<br />

battle-field, then to the resting place, finally to the ceremony of dedication. However, after pronouncing<br />

approbation of the ceremony (9), the speech denies its efficacy (10-11), <strong>and</strong> proceeds to subordinate it to<br />

larger <strong>and</strong> longer-lived concerns. The treatment of the event too, then, follows the movement of the whole<br />

discourse. The view of the ceremony is initially expansive, then narrowing to the moment, then increasingly<br />

encompassing again until it reaches the limit of mortal experience.<br />

The speech concludes with human concerns situated within their widest possible latitude <strong>and</strong> their<br />

longest possible duration: their scope is all of the world, <strong>and</strong> all of human history. Whatever is beyond that<br />

conclusion is beyond the human scale. Beyond it is the infinite: the venue of the supernal <strong>and</strong> the<br />

unknowable.<br />

Lincoln’s discourse propels us in the direction of metaphysical transcendence, but / it stops at the<br />

boundary. It exp<strong>and</strong>s to subsume all of life, but it ceases at the point where life ceases, where death <strong>and</strong><br />

infinity begin. Immediately beyond the scope of the discourse is ineffable mystery. The <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address<br />

speaks words to the world of words, <strong>and</strong> it echoes silence before the vast silence that begins where speaking<br />

ends.<br />

The speech is not just a vindication of the Civil War, or a poem to democracy, or a meditation on the<br />

legacies of the dead <strong>and</strong> the obligations of the living. It is also a map <strong>and</strong> a chronicle: it locates a burial<br />

ground in relation to all of space, <strong>and</strong> it fixes that moment of location in relation to all of time.<br />

The ceremony at <strong>Gettysburg</strong> had begun with a prayer by the Reverend Doctor T. H. Stockton which was<br />

three <strong>and</strong> a half times the length of Lincoln’s speech. With amplitude <strong>and</strong> confidence, the Reverend Doctor<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 8 of 8

Stockton expatiated on the relations between the casualties of battle <strong>and</strong> the divinity. But Lincoln, in his turn,<br />

does not presume to pronounce on the fate of the dead. He does not presume, even from his exalted office, to<br />

issue the consolation of spiritual immortality. There is no mitigation of bereavement, no anodyne, no<br />

euphemism, no benign illusion. He approaches the subject of the dead by approaching the realm of the dead,<br />

but approaching only, never pretending to intrude. He talks of the bequests of the dead, of their memorials,<br />

but not of their souls. He carries discourse <strong>and</strong> any claims to knowledge to the border of extinction <strong>and</strong><br />

eternity, to the outermost boundary of life <strong>and</strong> of time, but there he stops, <strong>and</strong> if that journey is to be<br />

continued, it must be in the imaginations of his auditors, for whom he has supplied a momentum <strong>and</strong> a<br />

trajectory.<br />

What is extraordinary about that momentum <strong>and</strong> trajectory is not the transcendent conception toward<br />

which they propel the auditor, because that conception is really quite orthodox. It is the Great Chain of<br />

Being: the majestic cosmology of medieval Christendom that links time with timelessness, the past with the<br />

future, history with destiny, life with death <strong>and</strong> both with immortality That cosmology is not affirmed in<br />

Lincoln’s speech, but neither is it to the slightest degree contravened. It is suggested by the biblical echoes<br />

that resound in the account of the nation’s genesis: “Four score <strong>and</strong> seven,” <strong>and</strong> fathering a nation, <strong>and</strong><br />

“brought forth.” 8 The distinction between dying, which may allow living on in another realm, <strong>and</strong> perishing<br />

from the earth, which implies anonymity <strong>and</strong> a complete cessation of existence, is also a reverberation of the<br />

King James Bible. 9<br />

The cosmology is an element of context---one with which Lincoln could be confident that his<br />

contemporary audiences would tacitly endow his speech. Lincoln knew his immediate audience’s general<br />

view of life <strong>and</strong> death, <strong>and</strong> he made his speech wholly compatible with that general view without committing<br />

himself to it. Lincoln’s tact confined him to exercising a solely secular authority.<br />

The cosmological implications of the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address are probably more disengaged in us than in<br />

Lincoln’s contemporaries. The idea of a Great Chain of Being is more faded in our time, a less active<br />

component of our convictions. We have, however, a perspective that is more than compensatory. It is<br />

augmented by the stronger sense of national identity that the Civil War made possible, <strong>and</strong> by our knowledge<br />

of Lincoln’s martyrdom, which lends the Address a poignancy that was unavailable to Lincoln’s<br />

contemporaries. In the end, then, we may infer that our responses are not quite equivalent in character to<br />

those of the immediate audience, but our responses may well be at least equivalent in intensity.<br />

CYCLES AND ARCHETYPES<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 9 of 9

At the beginning, the nation is brought forth, <strong>and</strong> at the end, the nation has a new birth of freedom. The issue,<br />

finally, is not the life <strong>and</strong> death of the fallen, but the life <strong>and</strong> death <strong>and</strong> resurrection of the nation. One cycle<br />

embedded in the speech is, of course, the life-cycle of birth <strong>and</strong> death. The speech touches only the terminal<br />

poles of the cycle. No reference to growth or maturation appears in the speech, so that no intermediate<br />

historical interpretation is offered except of the war itself, an interpretation so purified of immediate<br />

reference <strong>and</strong> so frugal of emotionality as to seem epiphanic (4-6).<br />

Another cycle, more subtly present, is decay <strong>and</strong> regeneration: the cycle in which organisms decompose<br />

into fertile organic matter <strong>and</strong> become nutriment for other organisms. The speech hints at that relation<br />

between the dead soldiers <strong>and</strong> the nation (8). It can do no more than hint; obviously, an overt equation<br />

between the honored dead <strong>and</strong> compost would be an offensive <strong>and</strong> unfeeling reduction. But an audience<br />

close to natural processes <strong>and</strong> seasons, as Lincoln’s predominantly rural contemporaries were, would be<br />

sensitive to that hint, <strong>and</strong> would take it without flinching. Their piety <strong>and</strong> grief would inhibit their making<br />

any indelicate extension of the figure within their own imaginations. The hint, of course, is purely figural.<br />

Lincoln implies, alludes to a metaphor without explicitly declaring it. The allusion is a parsimonious<br />

reminder of a natural process; only its context works to provoke its being associated, by analogy, with<br />

obituary or patriotic motifs. The compression is striking: the containment within a very few words of a<br />

complex <strong>net</strong>work of meaning.<br />

CEREMONIAL SPEECH<br />

Speaking has a variety of conventional functions. The most ordinary consist of conveying information—<br />

information about the world, or about oneself, or about one’s judgments of the world. Another less frequent<br />

but still familiar function of speaking is to settle a perdurable aura around an event--to commemorate it, or to<br />

celebrate it, or to endow it with significance. This function brings speech close to magic, not in the sense that<br />

words alone are expected to alter physical reality, but rather in the sense that words are expected to be<br />

constitutive, performative. The speech is to be itself a presence that is functionally indistinguishable from the<br />

event to which it alludes. The words that are spoken at ceremonial transitions work to fix <strong>and</strong> consign an<br />

event, to articulate a common interpretation of it, so to fashion a public memory of it that it can hardly<br />

thereafter be remembered in any other way This sort of speech conveys information in the strict sense in<br />

which anything called speech must convey information, but the information conveyed about the subject of<br />

ceremony is not new because the nature of that information is consensual, <strong>and</strong> the consensus has already<br />

been achieved prior to its expression. The conventional ceremonial speech aspires, at minimum, to declare<br />

that consensus, to dress an occasion in a socially necessary integument of words <strong>and</strong>, by remarking it, to<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 10 of 10

mark it as remarkable. This sort of perlocution occurs in recognition of the fact that although there are times<br />

when silence is tributary, there are also times when silence is contemptuous, when words must be spoken.<br />

Moments of beginning <strong>and</strong> of ending require speech as a rhetorical ordination.<br />

THE DEDICATORY FUNCTION<br />

The contrast between the living <strong>and</strong> the dead that pervades the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address is played against the<br />

subject of consecration, which is the ostensible task of the ceremony containing the speech <strong>and</strong> the ostensible<br />

issue of the speech itself. Lincoln says, in effect, that the living cannot consecrate the graveyard; the dead<br />

already have. So, the task of the living is some other: it is to continue the work that the dead had begun. By<br />

linking the social task of the living <strong>and</strong> the dead, the speech resists a bifurcation between life <strong>and</strong> death,<br />

positing in its place a relationship of continuity That continuity, in turn, reduces the distinction between<br />

honoring <strong>and</strong> being honored, replacing it with a relationship of common work—”unfinished work” (16)—<br />

<strong>and</strong> creating an equality between the living <strong>and</strong> the dead instead of the hierarchy that had prompted the<br />

ceremony. Honoring <strong>and</strong> being honored also participate in an active-passive diremption which is foregone in<br />

favor of a common, if temporally distinguishable, activity of consecration. The deadness of the dead is thus<br />

not contemplated. Rather, their deaths are interpreted to have been an action rather than a condition as the<br />

dead are shifted from being objects of reverence to being prefiguring participants in a common quest. And<br />

that flattening of the relationship comports with the historical perspective that the speech sponsors, because<br />

while the living <strong>and</strong> the dead live <strong>and</strong> died as individuals, it is the life of the nation that is paramount in this<br />

speech. The conception of individuality is subdued in the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address; its only subjects are<br />

aggregations. Its author has even effaced himself.<br />

The dead were brave men; the living is the nation. Lincoln flirts with paradox in rendering the dead, who<br />

no longer have identity, as a plurality of individuals, but rendering the living as a composite. However, the<br />

paradox enables Lincoln’s auditors to experience bereavement <strong>and</strong> yet simultaneously to dissolve their egos<br />

into a collective resolution. That elusive combination would enable the audience’s mourning to attain an<br />

impersonality <strong>and</strong> still to ache.<br />

There is a pun on “dedicated.” The dedication of the cemetery is transformed into the dedication of the<br />

audience. The synonyms of “dedication” can be divided into three groups of terms: First, “allegiance,<br />

commitment, devotion, loyalty”; second, “consecration, designation”; third, “ordination, address, inscription,<br />

message.” Lincoln begins with a focus on the middle terms---consecration <strong>and</strong> designation--both in relation<br />

to the official establishment of a cemetery. But in turning the subject of the dedication from the cemetery to<br />

the audience, the sense of the term shifts to the first four meanings: allegiance, commitment, devotion, <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 11 of 11

loyalty, especially the middle two of these four. And, of course, the last three senses--address, inscription,<br />

<strong>and</strong> message--are implicit in Lincoln’s very act of speaking.<br />

Lincoln rings the complete round of resonances of the term “dedication.” We cannot, he is saying,<br />

dedicate this cemetery because the dead have already done that. We should, therefore, dedicate ourselves.<br />

The implicit premise is that something must be dedicated--that, having come together for a dedication, the<br />

collection of people at <strong>Gettysburg</strong> are obliged to accomplish that task. The task that he proffers, however, is<br />

not capable of accomplishment at the ceremony itself. Lincoln poses a task that must occupy the audience<br />

beyond the ceremony. The speech, therefore, refuses to permit the ceremony to be a consummation, refuses<br />

to make it whole <strong>and</strong> complete. The speech rejects the ceremony as a vehicle of fulfillment. It does so by<br />

beginning its focus on the “consecration” sense of dedication, transforming it to the “commitment” sense<br />

<strong>and</strong>, in the process, shifting its subject, <strong>and</strong> it ends by rendering the dedicatory ceremony itself into the<br />

“message” sense.<br />

The inconclusiveness of the ceremony—Lincoln’s refusal to allow it to consummate the mourning of the<br />

dead—is entailed by the first sentence of the speech (2-3). The first reference to a dedication appears there.<br />

The subject of that dedication is, of course, the country, but its object is the statement of a cynosure, a<br />

proposition that can be taken only as teleological, the enunciation not of a fulfillment, but of a quest.<br />

CONTEXT<br />

We are taught to think of discourses dialectically. We underst<strong>and</strong> them in contexts: denying, qualifying,<br />

echoing, contesting other discourses. Discourses are participatory, <strong>and</strong> we comprehend them through their<br />

genealogy <strong>and</strong> genus. Edward Everett’s oration at <strong>Gettysburg</strong> echoes Daniel Webster’s epideictic mode; its<br />

set-piece on the battle aspires to Livy, with brushstrokes of Periclean melancholy. Everett’s speech is in a<br />

gr<strong>and</strong> ceremonial tradition, <strong>and</strong> it is through that tradition that we apprehend it. Its relationship to a family of<br />

other discourses is apparent, <strong>and</strong> even predictable.<br />

Lincoln’s <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address is unique in that instead of springing from a chorus of discourses that<br />

comprise its context, it grows from silence. The Address imposes its own order without reference to any<br />

other text. 10 It achieves whatever tension it requires not by its collision with alternatives, nor by its<br />

juxtaposition with precedents, but by its deliberate opposition to the occasion that prompted it. Instead of<br />

rejecting an implicit contradiction of itself, the Address rejects its own ostensible purpose: In so detaching<br />

itself from its own grounding, the speech gains a functional autonomy It makes itself incommensurable. Its<br />

sole alternative is not a contravening utterance, but a mortuary quietude.<br />

There is a recording of a 1944 performance by Wilhelm Furtwängler of the Freischütz overture. The<br />

opening chord of the overture—a long bass crescendo—seems to swell up out of nothing. It begins so quietly<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 12 of 12

that one’s first hearing is not of a chord beginning to be played, but of an already playing chord slowly<br />

developing into audibility. And part of the effect that Furtwängler creates in his miraculous performance is a<br />

consciousness of the void that has preceded the music. It is as if silence itself had found a voice. The<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address constructs a similar effect in its course. Unlike the subtle efflorescence with which<br />

Furtwängler performs Weber’s chord, the Address begins with a magisterial pronouncement on history; but it<br />

then proceeds so to disengage itself from other utterance that it ends finally as an articulation within<br />

nonbeing. It does not grow from a void; rather, it grows a void around itself. The speech presents itself sui<br />

generis.<br />

There is one other analogy to be drawn between the Furtwängler performance <strong>and</strong> the <strong>Gettysburg</strong><br />

Address. The way in which Furtwängler has his orchestra voice the first chord anticipates his interpretation<br />

of the whole composition. His entire performance is a playing out of the urgency <strong>and</strong> mystery that are coiled<br />

in that opening chord. The whole is implicit in its genesis. Similarly, the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address is an exfoliation<br />

of its first sentence. The threads of Lincoln’s tapestry are all plaited into that initial statement: the themes of<br />

religiosity, of historic continuity, of birth, of temporal movement, of the organic nation, of location, of<br />

dedication, <strong>and</strong> of unfulfilled aspiration. The whole of the discourse is a weaving of those threads.<br />

NEGATIVITY<br />

The negativity of the Address is striking: We cannot dedicate this cemetery. We resolve that the dead shall<br />

not have died in vain, that people’s government shall not perish. All are negatives. How curious that a speech<br />

should so powerfully survive, should so capture the popular imagination, should be marked as the greatest<br />

effusion of eloquence in the history of the country, <strong>and</strong> yet it is not cast affirmatively; rather, it denies, it<br />

disclaims, it negates.<br />

Along with the sure sense of what he knows <strong>and</strong> does not know, Lincoln also sustains in the speech a<br />

sense of the limits of language. The deeds of the soldiers are far more important than the speeches of the<br />

dedicators (10-15); the will <strong>and</strong> intention of people is superior to what is said (15-18). The speech evokes a<br />

sense of human effort transcending verbal expression, a sense of life <strong>and</strong> history eluding utterance. This<br />

aspect of the speech can be equated with mysticism: with the conviction that there are realities beyond the<br />

powers of articulation, ineffable forces that shape our lives.<br />

Without any overt allusion to a religious idea, without any invocation of the deity, Lincoln still manages<br />

to give his remarks a religious aura. The initial source of that aura is the biblical idiom of the first sentence,<br />

but its continuing source is the reflexive undercurrent in the Address: its contemplation of how unimportant<br />

<strong>and</strong> transitory speaking itself is (10-14), <strong>and</strong> of the fact that there are things not entailing speech--sentiments,<br />

intentions, resolutions, collective actions, values, ideals--that are important <strong>and</strong> enduring (15-23). The first<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 13 of 13

half of that message by itself--that the occasion is a fugitive moment--would be a message of humbling<br />

disenchantment; but the second half of the message--that some noble deeds <strong>and</strong> some dispositions of<br />

consciousness are beyond language--redeems the moment by embedding utterance within a nimbus of<br />

silence.<br />

The negativity of the Address is also an expression of its profound conservatism. The first sentence<br />

having announced the historical founding of a destiny, the speech serves the perpetuation of that original<br />

purpose. It refuses digressions. Like Lincoln’s presentation of the government’s role in the Civil War itself,<br />

the Address is concerned, most notably in its first <strong>and</strong> last sentences, with the conservation of a political idea<br />

<strong>and</strong> with the republic that instantiates it. Therefore, the Address would deny their alternatives.<br />

Grammatically, the concluding lines (22-23) are negative, but they negate an extinction, <strong>and</strong> so situate<br />

themselves as a nay-saying that affirms.<br />

The end of the Address is a resolution (20) that the establishment described in the first sentence will not<br />

be terminated: “we here highly resolve.” There is more than a single sense in which one may “highly<br />

resolve” something. One sense has to do with “resolve” in its sense of “making independently visible.” In<br />

that meaning, a high resolution may refer, for example, to a photograph that clarifies different colors <strong>and</strong><br />

volumes. Insofar as that sense of “highly resolve” is among its overtones, the phrase inclines the auditor to<br />

underst<strong>and</strong> resolving “that these dead shall not have died in vain” to constitute a clarity of disclosure--a<br />

resolution that we not only undertake but also one that we behold with a new precision--a statement of the<br />

essence not only of the speech up to that point, but also of its occasion <strong>and</strong>, beyond them both, of its living<br />

subject, the nation. The second sense--obviously closer to the center of Lincoln’s intention--is a use of the<br />

term “highly” to suggest loftiness, intensity, solemnity, nobility. Such attributes of our “resolve” elevate the<br />

dignity of the promise that the deaths will be purposeful. And there is a reason, even beyond the intrinsic<br />

sobriety of the task, to make such a resolve most solemn.<br />

In calling for the resolve that the dead shall not have died in vain, Lincoln is summoning his audience to<br />

perform an act of redemption: a redemption of the dead. To suggest that it is for us to redeem the dead could<br />

easily be construed as a sacrilege. The redemption of the dead, after all, would be regarded by Lincoln~<br />

contemporaries as a divine prerogative. Lincoln is advancing a secular version of redemption in the only way<br />

in which he tactfully can, <strong>and</strong> that is by the indirection of a negative construction. For him to have put the<br />

idea in a positive mode would have been too stark a revelation of his work to sanctify the nation <strong>and</strong> its<br />

defining principles.<br />

Suppose the speech were not rewritten, but simply rearranged so that it ended with an affirmative<br />

statement. Suppose that, by more clearly echoing the beginning of the speech at its end, the rearrangement<br />

transmuted the Address into “that most pervasive of all rhetorical figures in ancient literature <strong>and</strong> even in<br />

modern, the ring-composition.’’ 11 Suppose the last few lines went:<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 14 of 14

. . . that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the<br />

last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in<br />

vain—that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the<br />

earth—<strong>and</strong> that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.<br />

No reader of this rearrangement who has had a lifetime’s memory of the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address can quite<br />

renounce the influence of the original. Yet, even after the most earnest deference to the probability of<br />

prejudice, the suspicion persists that the rhythm of the conclusion is debased by the rearrangement. The<br />

revision is too brusque. It is a terminus, but it is no longer a coda. It has gained positive declaration at the<br />

cost of majesty. The original ending has a tetrad of phrases, each composed of a tetrad of beats—“of the<br />

people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish” —followed by a single, emphatic, unaccented triad:<br />

“from the earth.” The rhythmic indeterminacy of the rearranged ending must compare unfavorably to this<br />

solemn cadence, which measures out the final lines (20-23) with a gravity corresponding to their determinacy<br />

of purpose.<br />

USES OF 1RONY<br />

The <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address is a sacramental act. Its procedure is to abjure its own efficacy. It is through the<br />

process of that abjuration that it achieves its character. The speech affirms by negating; it makes itself into an<br />

eloquent confession of inarticulateness; it gains celebrity by seeking obscurity; it commemorates the dead by<br />

obligating the living; it masters an occasion by retreating from it, <strong>and</strong> culminates a dedication by protracting<br />

it.<br />

The speech abounds in ironies, in transformative disruptions of convention. And that condition of<br />

multifaceted reversal is itself a composite irony because its source is the head of a government who is<br />

resisting a rebellion. In rotating a meaning into its opposite, an irony is a miniature verbal revolution, <strong>and</strong> so<br />

it is supremely ironic to use irony in resistance to a revolution. 12 Lincoln at <strong>Gettysburg</strong> pre-empted the<br />

essential tool of his adversaries, whose most pe<strong>net</strong>rating minds were less pe<strong>net</strong>rating than his, <strong>and</strong> whose<br />

most agile wits were, compared to his wit, cumbrous.<br />

DIANOIA AND ETHOS<br />

It is only after one has recovered from the spell of the speech, <strong>and</strong> comes to realize that it is, after all, the<br />

product of a mind, that the character of that mind can be considered. On its most superficial level, the speech<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 15 of 15

is asymptomatic. It is inexpressive. It displays nothing of the speaker except his mighty powers of<br />

comprehension, but even that display seems inadvertent. That is, the speech proposes no more of the mind<br />

behind it than any speech—even the most spontaneous imaginable—necessarily proposes. The plays of<br />

Shakespeare reveal little of the attitudes of Shakespeare; but they reveal abundantly that the magnitude of his<br />

mind was beyond measure. By contrast, the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address does reveal some of the attitudes of Lincoln<br />

simply because, unlike the multifarious voices of a Shakespearian drama, its voice is the distinctive voice of<br />

its author, but the design of the Address distances the personality of Lincoln. The subordination of the<br />

occasion to historic considerations perforce subordinates also the orator—subordinates him to the point of<br />

invisibility. Lincoln does not intrude into the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address. He is not a reference in the speech, not<br />

literally, not even by specific implication. What presence he has in the speech is solely the product of<br />

linguistic necessity. He is present only to the extent that a speech requires a speaker.<br />

The <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address initiated a process of deliberate self-effacement that Lincoln conducted until his<br />

death. It was a process that reached its public culmination in the Second Inaugural Address.<br />

Here is the beginning of the Second Inaugural Address. Forget for a moment Lincoln’s reputation as an<br />

orator. Attend instead to the tortured construction of the language:<br />

At this second appearing to take the oath of the Presidential office there is less occasion for an<br />

extended address than there was at the first. Then a statement somewhat in detail of a course to be<br />

pursued seemed fitting <strong>and</strong> proper. Now, at the expiration of four years, during which public<br />

declarations have been constantly called forth on every point <strong>and</strong> phase of the great contest which<br />

still absorbs the attention <strong>and</strong> engrosses the energies of the nation, little that is new could be<br />

presented.... On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago all thoughts were anxiously<br />

directed to an impending civil war.... While the inaugural address was being delivered from this<br />

place, devoted altogether to saving the Union without war, insurgent agents were in the city<br />

seeking to destroy it without war...<br />

Lincoln was a masterly stylist; yet, these are curiously strained sentences, their contortion exacerbated by<br />

their presence in a speech with some of the most magnificent passages in the history of the language. Those<br />

beginning sentences are bent <strong>and</strong> twisted to avoid self-reference. During an inauguration—an occasion when,<br />

of all occasions, attention would be invited to the person who is the subject of the ceremony—Lincoln labors<br />

to escape being present in his speech.<br />

The Second Inaugural Address has only two uses of the first-person singular, both in the same sentence:<br />

“The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well known to the public as to myself,<br />

<strong>and</strong> it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory <strong>and</strong> encouraging to all.” The context of “myself’ is a disclaimer of<br />

special knowledge, <strong>and</strong> the context of “I trust” is, in effect, a disclaimer of superior knowledge. “I trust” also<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 16 of 16

etards <strong>and</strong> enhances the rhythm of the sentence. None of these functions exalt the speaker. The implicit<br />

disclaimers, in fact, signal his humility. In this speech, as in the precursive <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address, Lincoln had<br />

so refined his vision of his role <strong>and</strong> had so purified his expression of that vision, that he had all but<br />

extinguished his own authorial presence.<br />

The rigor of Lincoln’s self-discipline is given salience by its contrast to Everett’s expansive speech.<br />

Everett reconstructed the battles of <strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong>, beyond them, a sufficient sampling of the history of<br />

warfare to subsume them to a heroic perspective. It was a virtuoso performance, inhibited by neither timidity<br />

nor reticence. The echoes of Everett’s ambitious narrative had not wholly faded when the laconic Lincoln<br />

spoke what he knew.<br />

The <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address is, finally <strong>and</strong> inevitably, a projection of Lincoln himself, of his discretion, of<br />

his modesty on an occasion which invited him to don the mantle of the prophet, of his meticulous measure of<br />

how far he ought to go, of the assurance of his self-knowledge: his impeccable discernment of his own<br />

competence, his flawless sense of its depth <strong>and</strong> its limits. As an actor in history <strong>and</strong> a force in the world,<br />

Lincoln does not hesitate to comprehend history <strong>and</strong> the world. But he never presumes to cast his mind<br />

beyond human dimensions. He does not recite divine intentions; he does not issue cosmic judgments. He<br />

knows, to the bottom, what he knows. Of the rest, he is silent.<br />

NOTES<br />

2 Edgar Lee Masters, Lincoln, The Man (New York: Dodd-Mead, 1931) esp. 478-498. Masters argues, in this angry biography, that<br />

Lincoln hypnotized the country, to its ruin.<br />

3 Garry Wills, Lincoln at <strong>Gettysburg</strong>: The Words that Remade America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992) 145-147.<br />

4 Early reception of the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address is surveyed by William E. Barton, Lincoln at <strong>Gettysburg</strong>: What He Intended to Say;<br />

What He Said; What He was Reported to Have Said; What He Wished He had Said (New York: Peter Smith, 1950) 89-92 <strong>and</strong> 114-<br />

123. Other initial responses to the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address, pro <strong>and</strong> con, have been collected by Svend Petersen, The <strong>Gettysburg</strong><br />

Addresses: The Story of Two Orations (New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing (1963) 53-64. Petersen has also collected parodies of<br />

the Address, pp. 65-94. They are uniformly dreary.<br />

5 Wills’s admirable Lincoln at <strong>Gettysburg</strong> is the most recent <strong>and</strong> arguably the most accomplished effort to scale the summit of the<br />

Address. Wills has anchored virtually every word of the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address to its historical antecedents in a meticulous<br />

documentation of its sources, its context, <strong>and</strong> its effects. Yet, not even Wills’s excellent book has said all that there is to say about<br />

the construction <strong>and</strong> dynamics of the text. Nor, indeed, does it claim to.<br />

6 Bernard Berenson, Aesthetics <strong>and</strong> History, (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Co., 1954) 92: “... respirational values.., refer to our<br />

feelings of liberation, of freedom from heaviness, <strong>and</strong> to the illusion of soaring into harmonious relations with sky <strong>and</strong> horizon.”<br />

7 Barton observed the absence from the Address of the first-person singular in Lincoln at <strong>Gettysburg</strong>, 149. In comparing Lincoln~<br />

selfless performance with later speeches given at <strong>Gettysburg</strong> by Woodrow Wilson <strong>and</strong> Theodore Roosevelt, Barton is surprised to<br />

find that Roosevelt was, like Lincoln, “wholly impersonal.” Wilson, however, referred to himself more than once a minute. See<br />

Barton 149-151.<br />

8 It is reasonable to suspect that the namesake of Abraham was especially attentive to those passages in the King James Bible that<br />

discussed Abraham. For example, Genesis 16:16 reports: “And Abram was fourscore <strong>and</strong> six years old, when Hagar bare Ishmail to<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 17 of 17

Abram.” In Genesis 17:5 God issues a directive: “Neither shall thy name any more be called Abram, but thy name shall be Abraham;<br />

for a father of many nations have I made thee.” For “brought forth,” see Genesis 1:20 <strong>and</strong> 1:24.<br />

9 See, for example, Job 18:17: “His remembrance shall perish from the earth, <strong>and</strong> he shall have no name in the street.” And Job<br />

34:14-15: “If he set his heart upon man if he gather unto himself his spirit <strong>and</strong> his breath; All flesh shall perish together, <strong>and</strong> man<br />

shall turn again unto dust.” Also John 3:16: “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever<br />

believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.”<br />

10 There are textual antecedents for the Address, but the Address contains no references to them. Lincoln had long been contending<br />

that slavery could not be contained, that ultimately it would have either to be universal or wholly abolished. See, for example, his<br />

“House Divided” Speech to the Republican State Convention, Springfield, Illinois, 16 June 1858, esp.: “I believe this government<br />

cannot endure, permanently half slave <strong>and</strong> half free.”<br />

Lincoln had also advanced juridical arguments on the indivisibility of the nation, most notably in his First Inaugural Address, 4<br />

March 1861, esp.: “I hold that, in contemplation of universal law <strong>and</strong> of the Constitution, the Union of these States is perpetual.”<br />

In his Message to Congress of 4 July 1861 Lincoln argued that the attack on Fort Sumter presented issues of principle that<br />

transcended even the nation:<br />

It presents to the whole family of man, the question, whether a constitutional republic, or a democracy--a government of the<br />

people, by the same people--can, or cannot, maintain its territorial integrity, against its own domestic foes. It presents the<br />

question, whether discontented individuals, too few in numbers to control administration, according to organic law, in any<br />

case, can always, upon the pretences made in this case, or on any other pretences, or arbitrarily, without any pretence, break up<br />

their Government, <strong>and</strong> thus practically put an end to free government upon the earth.<br />

Lincoln already had the germs of his conclusion (“government of the people, by the same people” <strong>and</strong> “an end to free government<br />

upon the earth”) over two years before the Address.<br />

11 Roger A. Hornsby, “The Relevance of Ancient Literature: Recapitulation <strong>and</strong> Comment,” Papers in Rhetoric <strong>and</strong> Poetic, ed.<br />

Donald C. Bryant (Iowa City, University of Iowa Press: 1965) 95.<br />

12 There was in Lincoln’s day, as there is now, a common distinction between the terms “rebellion” <strong>and</strong> “revolution.” Webster~<br />

Third New International Dictionary quotes Instructions for Government of U.S. Armies: “The term ‘rebellion’ is applied to an<br />

insurrection of large extent, <strong>and</strong> is usually a war between the legitimate government of a country <strong>and</strong> portions or provinces of the<br />

same who seek to throw off their allegiance to it <strong>and</strong> set up a government of their own.” The same source defines “revolution” as “a<br />

fundamental change in political organization or in a government or constitution.”<br />

Lincoln merged the two conceptions in the final section of the <strong>Gettysburg</strong> Address. He made the effect of the rebellion to be<br />

revolutionary. Its success, he was saying, would extinguish the form of government entailed in the genesis of the nation, a claim he<br />

had warranted in earlier discourses. See, for example, the Message to Congress of 4 July 1861.<br />

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 18 of 18

<strong>Gettysburg</strong> <strong>and</strong> silence; The Quarterly Journal of Speech, Ann<strong>and</strong>ale; Feb 1994; Vol. 80, Issue 1 Page 19 of 19