View - BANTAO Journal

View - BANTAO Journal

View - BANTAO Journal

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

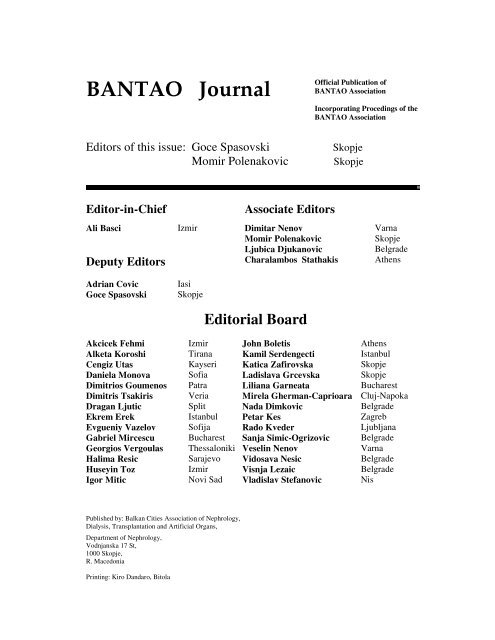

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong><br />

Editors of this issue: Goce Spasovski<br />

Momir Polenakovic<br />

Official Publication of<br />

<strong>BANTAO</strong> Association<br />

Incorporating Procedings of the<br />

<strong>BANTAO</strong> Association<br />

Skopje<br />

Skopje<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Associate Editors<br />

Ali Basci Izmir Dimitar Nenov Varna<br />

Momir Polenakovic<br />

Skopje<br />

Ljubica Djukanovic<br />

Belgrade<br />

Deputy Editors Charalambos Stathakis Athens<br />

Adrian Covic<br />

Goce Spasovski<br />

Iasi<br />

Skopje<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Akcicek Fehmi Izmir John Boletis Athens<br />

Alketa Koroshi Tirana Kamil Serdengecti Istanbul<br />

Cengiz Utas Kayseri Katica Zafirovska Skopje<br />

Daniela Monova Sofia Ladislava Grcevska Skopje<br />

Dimitrios Goumenos Patra Liliana Garneata Bucharest<br />

Dimitris Tsakiris Veria Mirela Gherman-Caprioara Cluj-Napoka<br />

Dragan Ljutic Split Nada Dimkovic Belgrade<br />

Ekrem Erek Istanbul Petar Kes Zagreb<br />

Evgueniy Vazelov Sofija Rado Kveder Ljubljana<br />

Gabriel Mircescu Bucharest Sanja Simic-Ogrizovic Belgrade<br />

Georgios Vergoulas Thessaloniki Veselin Nenov Varna<br />

Halima Resic Sarajevo Vidosava Nesic Belgrade<br />

Huseyin Toz Izmir Visnja Lezaic Belgrade<br />

Igor Mitic Novi Sad Vladislav Stefanovic Nis<br />

Published by: Balkan Cities Association of Nephrology,<br />

Dialysis, Transplantation and Artificial Organs,<br />

Department of Nephrology,<br />

Vodnjanska 17 St,<br />

1000 Skopje,<br />

R. Macedonia<br />

Printing: Kiro Dandaro, Bitola

Congress report<br />

The dream is now a reality - The seventh Congress of the Balkan<br />

Cities Association of Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation and<br />

Artificial Organs (<strong>BANTAO</strong>) Ohrid, Republic of Macedonia, 8-11<br />

September 2005<br />

The 7 th <strong>BANTAO</strong> Congress was held from 8 th to 11 th September<br />

2005 in Ohrid, Republic of Macedonia. Ohrid is also the place where<br />

<strong>BANTAO</strong> was born in October 9 th , 1993.<br />

The main goal of <strong>BANTAO</strong> is to promote scientific and technical<br />

cooperation in the fields of renal disease and artificial organs among the<br />

Balkan cities, giving an opportunity for exchange of experience and<br />

knowledge among the experts in the area and to engage them in<br />

collaborative projects in order to demonstrate that cooperation is possible<br />

even on the turbulent Balkan Peninsula.<br />

Following the first six successful congresses: Varna (1995),<br />

Belgrade (1998), Izmir (1999), Thessaloniki (2001) and Varna (2003),<br />

the <strong>BANTAO</strong> Congress was established as the major and institutional<br />

forum for Balkan nephrologists, with its own journal including our will<br />

to communicate, to collaborate, to get to know each other and to share<br />

our difficulties. More than just a professional event, the <strong>BANTAO</strong><br />

congress became a cultural phenomenon, through which we discovered<br />

that we have many more things in common than we previously thought,<br />

and that we must now take every advantage of being able to live and to<br />

communicate in a world without political boundaries. At present, the<br />

<strong>BANTAO</strong> Council has managed in a spirit of peace, friendship and<br />

collaboration to continuously strengthen this association and moreover,<br />

to make it a reputable part of the European and international ones. In this<br />

spirit the constitution of <strong>BANTAO</strong> has already been created.<br />

The Congress was attended by 570 physicians from the Balkan<br />

Peninsula cities as well as from Europe and USA. The Congress was<br />

held under the patronage of the President of the Republic of Macedonia,<br />

Mr. Branko Crvenkovski, Prof. M. Polenakovic was the Congress<br />

President and Doc. G. Spasovski the Secretary General.<br />

In the fields of the Epidemiology of Renal Disease, Basic Science,<br />

Clinical Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation and Artificial Organs we<br />

had 43 invited guest lectures, 42 oral and 223 poster presentations.<br />

The Congress was focused on several topics for example: how to<br />

improve the Balkan renal registry, prevention in nephrology, prevention<br />

of progression of renal diseases, understanding renal fibrosis and kidney<br />

transplantation on the Balkan Peninsula.

Companies invited speakers presented in six symposia, one<br />

workshop and three mini lectures their latest achievements in specific<br />

fields of nephrology, especially in dialysis.<br />

R. Vanholder, A. Perna, J. Jankowski and A. Argiles, on behalf of<br />

ESAO/EUTOX group, presented: An update on uremic toxicity- the role<br />

of EUTOX. D. Kerjaschki and H. Regele presented clinico-pathological<br />

correlation in renal transplant patients.<br />

For the first time at this 7 th <strong>BANTAO</strong> Congress we organized<br />

CME Course - Frontiers in nephrology, sponsored by ERA/EDTA and<br />

ISN/COMGAN. Six distinguished speakers: F. Locatelli, J. Mann, J.<br />

Floege, T. Risler, A. Wiecek, and M. Klinger presented the newest<br />

achievements in their fields.<br />

The abstracts were published in <strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Vol. 3 (1),<br />

2005, pp 1-121, editor G. Spasovski as Abstract Book and 50 papers<br />

from the Congress in the <strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> Vol. 3 (2), 2005, pp 1-160,<br />

as Proceedings of the 7 th <strong>BANTAO</strong> Congress, editors G. Spasovski and<br />

M. Polenakovic. A. Basci (Izmir) was elected Editor in Chief. A. Covic<br />

(Iasi) and G. Spasovski (Skopje) were elected as deputy editors.<br />

The 7 th Congress of <strong>BANTAO</strong>, Ohrid, was a resounding success<br />

and confirmed our good will for mutual collaboration and friendship, so<br />

we can say our dream is now a reality.<br />

M. Polenakovic was elected President of <strong>BANTAO</strong> Association.<br />

The next - 8 th <strong>BANTAO</strong> Congress will be held in Belgrade in 2007. Prof.<br />

Ms. V. Nesic was elected as President of the Congress.<br />

M. Polenakovic<br />

G. Spasovski

Preface<br />

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> is an official publication of the <strong>BANTAO</strong><br />

Association. The aim/intention of the <strong>Journal</strong> is to cover the issues of<br />

early diagnosis, prevention and treatment of kidney diseases, as well as<br />

other specific problems Balkan nephrologists are facing with.<br />

The <strong>Journal</strong> should improve the medical education and knowledge<br />

of nephrologists and other doctors through an integrative process for<br />

appropriate management of chronic kidney disease (CKD) as an<br />

increasing worldwide problem.<br />

After the successful 7 th <strong>BANTAO</strong> Congress in Ohrid, September<br />

2005, a need to improve Balkan renal registry, the early diagnosis of<br />

CKD, prevention and management of renal diseases in order to postpone<br />

the development of end stage renal failure (ESRF) was imposed.<br />

Papers published in this volume are dedicated to aforementioned<br />

problems, presented during our last <strong>BANTAO</strong> Congress. At the General<br />

Assembly of our <strong>BANTAO</strong> Association, A. Basci (Izmir) was elected<br />

Editor in Chief. A. Covic (Iasi) and G. Spasovski (Skopje) were elected<br />

as Deputy Editors. We congratulate them and wish a good and successful<br />

work in the <strong>Journal</strong>.<br />

Guest Editors of this issue:<br />

Momir Polenakovic<br />

President of <strong>BANTAO</strong> Association<br />

Goce Spasovski<br />

Deputy Editor of the <strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>

Contents:<br />

Correlation between sera levels of sVCAM-1 and severity of kidney lesions in<br />

patients with lupus nephritis<br />

T. Ilic, I. Mitic, B. Milic and S. Curic......................................................................................... 1<br />

Continuous convective renal replacement (CCRR) system: A new modality of<br />

wearable artificial kidney<br />

M.N. Aboras and I.A. Kawalit…………………………………………………………………. 3<br />

Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in dialysis patients<br />

P. Dzekova, A. Slavkovska, L. Simjanovska, I. Nikolov, A. Sikole, R. Grozdanovski,<br />

A. Asani, G. Selim, S. Gelev, V. Amitov, G. Spasovski and M. Polenakovic............................ 6<br />

Influence of inflammation on nutritional status of dialysis patients<br />

P. Dzekova, I. Nikolov, G. Severova-Andreevska, A. Sikole, R. Grozdanovski, A. Asani,<br />

G. Selim, S. Gelev, V. Amitov, G. Spasovski and M. Polenakovic……………………………. 8<br />

Unfavorable prognostic factors in Immunoglobulin A Nephropathy<br />

L. Petrovic, S. Curic, I. Mitic, D. Bozic, S. Vodopivec, V. Sakac, T. Djurdjevic-Mirkovic<br />

and T. Ilic……………………………………………………………………………………...... 10<br />

Congestive heart failure and renal dysfunction<br />

D. Monova, E. Peneva and S. Monov………………………………………………………….. 13<br />

Sporadic Balkan Endemic Nephropathy (BEN) beyond the known regions of<br />

BEN<br />

J. Nikolic, T. Pejcic, D. Crnomarkovic, Z. Gavrilovic and C. Tulic…………………………… 15<br />

Amyloidosis in Turkish patients<br />

C. Ensari and A. Ensari………………………………………………………………………... 18<br />

Frequency of Alport syndrome at dialysis center “Vrsac”- Vrsac<br />

K. Djordjev, D. Tintor, G. Djurdjev, O. Vasilic-Kokotovic, I. Sokolovac and S. Bozic………. 21<br />

Eearly effects of the AT 2 receptor antagonist eprosartane mesylate (EM) in<br />

diabetic patients with and without chronic renal failure<br />

N. Nnchev, B. Deliyska, M. Bankova, P. Radulova, G. Kimenov and E. Marinova…………. 23<br />

Prealbumin and inflammatory markers in dialysis patients<br />

S. Chrysostomou, K. A. Poulia, Y. Jeanes, D. Perrea, M. Poulakou, B. Filiopoulos,<br />

D. Stamatiades and Ch. P. Stathakis…………………………………………………………… 26<br />

Liver and kidney damage in acute poisonings<br />

M. Mydlik and K. Derzsiova…………………………………………………………………… 30<br />

Vascular calcifications in patients on hemodialysis<br />

T. Damjanovic, N. Markovic, S. Djorovic, T. Djordjevic and N. Dimkovic………………… 34<br />

Is there a seasonal variation in mortality in hemodialysis patients?<br />

J. Popovic, N. Dimkovic, Z. Djuric, G. Popovic and N. Lazic………………………………… 36<br />

Propyl gallate-induced platelet aggregation in patients with end stage renal<br />

disease – The influence of the hemodialysis procedure<br />

T. Eleftheriadis, G. Antoniadi, V. Liakopoulos, A. Tsiandoulas, K. Barboutis<br />

and I. Stefanidis……………………………………………………………………….………... 40<br />

Serum cystatin C as an endogenous marker of kidney function in elderly with<br />

chronic kidney failure<br />

H. Resic and A. Mataradzija…………………………………………………………………… 46

Thyroid disfunction and ultrasonographic abnormalities in uremic patients<br />

undergoing conservative management and haemodialysis<br />

A. Mataradzija , H. Resic and E. Kucukalic-Selimovic…………………………………………. 50<br />

Prednisone/Cyclophosphamide treatment in adult-onset autosomal dominant<br />

familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS 1)<br />

L. Grcevska, S. Dzikova, V. Ristovska, M. Milovanceva Popovska, G. Petrusevska<br />

and M. Polenakovic…………………………………………………………………………….. 56<br />

Microalbuminuria – The new marker for Balkan Endemic Nephropathy?<br />

G. Imamovic, S. Trnacevic, M. Tabakovic, E. Mesic, M. Uzeirbegovic, M. Malohodzic, A.<br />

Halilbasic, V. Habul, D. Tulumovic, E. Hodzic, M. Atic, S. Lekic M. Dugonjic,<br />

A. Becirovic and E. Hasanovic..................................................................................................... 58<br />

Lymphatic neoangiogenesis in human neoplasia and transplantation as<br />

experiments of nature<br />

D. Kerjaschki…………………………………………………………………………………… 60<br />

Cytokines and acute renal failure<br />

K. Cakalaroski………………………………………………………………………………….. 62<br />

Amyloidosis<br />

M. Tunca……………………………………………………………………………………….. 66<br />

Oxidative stress evaluation in uraemic patients undergoing continuous<br />

ambulatory peritoneal dialysis<br />

G. Mircescu, C. Capusa, I. Stoian, D. Lixandru, E. Rus, L. Coltan and L. Gaman…….……… 69<br />

Hyperhomocysteinemia in ESRD<br />

A. F. Perna, C. Lombardi, R. Capasso, F. Acanfora, E. Satta, D. Ingrosso,<br />

M. G. Luciano and N. G. De Santo.............................................................................................. 74<br />

C.E.R.A. (Continuous Erythropoietin Receptor Activator): A new perspective<br />

in anaemia management<br />

W. Sulowicz……………………………………………………………………………………. 78<br />

Diagnosis and treatment of renal bone disease<br />

G. B. Spasovski………………………………………………………………………………… 82<br />

Efficiency of mycophenolate-mofetil in resistant nephrotic syndrome – case<br />

reports<br />

B. Milic, T. Ilic, I. Mitic, I. Budosan and S. Curic……………………………………………... 84<br />

Bacterial infections associated with double lumen central venous catheters<br />

M. S. Simin, M. Milosevic, S. Vodopivec, I. Mitic and S. Curic……………………………… 86<br />

Early renal protocol biopsies: beneficial effects of treatment of borderline<br />

changes and subclinical rejections on the histological changes for chronic<br />

allograft nephropathy<br />

J. Masin-Spasovska, N. Ivanovski, S. Dzikova, G. Petrusevska, B. Dimova, Lj. Lekovski,<br />

Z. Popov and G. Spasovski……………………………......................………………............... 88<br />

Factors associated with carotid and femoral atherosclerosis in non-diabetic<br />

hemodialysis patients<br />

S. Gelev, S. Dzikova, A. Sikole, Gj. Selim, P. Dzekova, V. Amitov and G. Spasovski............. 93<br />

Acid-base disorders in patients with hypoproteinemia<br />

P. Mavromatidou, N. Sotirakopoulos, T. Tsitsios, I. Skandalos, M. Peiou,<br />

and K. Mavromatidis.................................................................................................................... 99<br />

Instructions to authors…………………………………………………………………...… 104

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> 2006: 4 (1): 1<br />

Correlation between sera levels of sVCAM-1 and severity of kidney lesions<br />

in patients with lupus nephritis<br />

T. Ilic, I. Mitic, B. Milic and S. Curic<br />

Department of Nephrology, Clinical Center Novi Sad, Serbia and Montenegro<br />

Abstract<br />

We determined sera concentrations of soluble vascular<br />

adhesion molecule-1 (sVCAM-1) in group of 80 patients with<br />

SLE. Our aim was to investigate correlation between level of<br />

sVCAM-1 and degree of disease activity, also severity of<br />

lupus nephritis. Using ELISA procedure we determined sera<br />

levels of sVCAM-1 in 80 patients with SLE and in group of<br />

27 healthy volunteers. Patients with SLE had significantly<br />

higher sera levels of sVCAM-1 comparing healthy controls<br />

(p < 0,001). Patients with disease in active phase had higher<br />

sera levels of this adhesive molecule comparing patients with<br />

disease in phase of remission (p < 0,001). There was a high<br />

positive correlation between sera levels of sVCAM-1 and<br />

concentration of anti-ds DNK antibodies in sera of patients<br />

with SLE (r = 0,77, p < 0,001) and there was also negative<br />

correlation between sera levels of sVCAM-1 and sera<br />

concentrations of C 3 and C 4 component of complement (r = -<br />

0,64, r = - 0,58). In group of patients with lupus nephritis<br />

were detected significantly higher sera concentrations of<br />

sVCAM-1 comparing patients without nephritis. Using WHO<br />

classification, patients with lupus nephritis were systematized<br />

in three categories: class II (5 patients), classes III and IV (18<br />

patients) and class V (7 patients). Patients with class III and<br />

class IV of kidney changes had significantly higher levels of<br />

sVCAM-1 comparing patients with class II of kidney<br />

changes. At the same time, in group of patients with activity<br />

index (AI) of kidney changes over 4 sVCAM-1 sera levels<br />

were significantly higher comparing group with AI < 4. Sera<br />

level of sVCAM-1 is reliable parameter in evaluation of<br />

autoreactivity degree in SLE. At the same time, sVCAM-1<br />

sera level can be used as reliable marker in evaluation of<br />

renal lesion extensivity in SLE.<br />

Key words: SLE, sVCAM-1, lupus nephritis<br />

Introduction<br />

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is chronic, inflamatory<br />

connective tissue disease which contains loss of<br />

autotolerancy as main immunological disorder accompanied<br />

with breakdown of T lymphocytes, collapse of cytokine<br />

production and B lymphocite hiperactivity (1). Cytokines are<br />

essential regulating factors of immunology response which<br />

are included in migration process of inflammatory cells into<br />

the place of immunology caused inflammatory tissue<br />

reaction, together with adhesive molecules (2). The vascular<br />

cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) is a member of the<br />

immunoglobulin gene superfamily. VCAM-1 supports the<br />

adhesion of lymphocytes, monocytes, natural killer cells,<br />

eosinophils and basophils through its interaction with<br />

leukocyte very late antigen-4 (VLA-4). VCAM-1/VLA-4<br />

interaction mediates firm adherence of circulating nonneutrophilic<br />

leukocyte to endothelium. VCAM-1 also<br />

participates in leukocyte adhesion outside of the vasculature,<br />

mediating presursor lymphocyte adhesion to bone marrow<br />

stromal cells and B cell binding to lymph node follicular<br />

dendritic cells (3). A soluble form of VCAM-1 (sVCAM-1)<br />

has been described. Soluble VCAM-1 levels have been found<br />

in the sera of healthy individuals and increased levels of<br />

sVCAM-1 can be detected in several diseases including<br />

connective tissue diseases (4). Studies have shown that<br />

elevated levels of sVCAM-1 are related to disease activity in<br />

patients with SLE (5).<br />

The aim of our study was to investigate changes of adhesive<br />

molecule sera levels in patients with SLE comparing different<br />

phases of disease activity and comparing presence/absence of<br />

lupus nephritis. At the same time relation of vascular cell<br />

adhesion molecule sera concentrations were analized with<br />

concentrations of other disease parameters (titre of ANA,<br />

SLED AI, titre of anti-ds DNA antibodies, concentrations of<br />

C3 and C4).<br />

Patients and methods<br />

The study was carried out in 80 patients included in<br />

crossection study and 10 patients included in longitudinaly<br />

study. We used ELISA procedure to determine sVCAM-1<br />

sera levels in 80 patients with SLE and in group of 27 healthy<br />

volunteers. An anti-sVCAM-1 monoclonal coating antibody<br />

is adsorbed onto microwells. sVCAM-1 present in the sample<br />

binds to antibodies adsorbed to the microwells. A mixtureof<br />

biotin–conjugated monoclonal anti-sVCAM-1 antibody and<br />

Streptavidin–HRP is added. Biotin conjugated anti-sVCAM-<br />

1 captured by the first antibody. Streptavidin-HRP binds to<br />

the biotin conjugated anti-VCAM-1. Following incubation<br />

unbound biotin conjugated anti-sVCAM-1 and Streptavidin –<br />

HRP is removed during a wash step and substrate solution<br />

reactive with HRP is added to the wells. Acoloured product is<br />

formed in proportion to the amount of soluble VCAM-1<br />

present in the sample. The reaction is terminated by addition<br />

of acid and absorbance is measured at 450 nm. A standard<br />

curve is prepared from six sVCAM-1 standard dilutions and<br />

sVCAM-1 sample concentration determined.<br />

______________________<br />

Correspodence to: T. Ilic, Department of Nephrology, Clinical Center Novi Sad, Serbia and Montenegro

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> 2006: 4 (1): 2<br />

Results and discussion<br />

Patients with SLE had significantly higher sera levels of<br />

sVCAM-1 comparing healthy controls (p < 0,001). Patients<br />

with disease in active phase had higher sera levels of this<br />

adhesive molecule comparing patients with disease in phase<br />

of remission (p < 0,001). There was high positive correlation<br />

between sera levels of sVCAM-1 and concentration of anti-ds<br />

DNK antibodies in sera of patients with SLE (r = 0,77, p <<br />

0,001) and a negative correlation between sera levels of<br />

sVCAM-1 and sera concentrations of C 3 and C 4 component<br />

of complement (r = -0,64, r = - 0,58). In group of patients<br />

with lupus nephritis a significantly higher sera concentrations<br />

of sVCAM-1 were detected comparing patients without<br />

nephritis. Using WHO classification, patients with lupus<br />

nephritis were systematized in three categories: class II (5<br />

patients), classes III and IV (18 patients) and class V (7<br />

patients). Patients with class III and class IV of kidney<br />

changes had significantly higher levels of sVCAM-1<br />

comparing patients with class II of kidney changes. In the<br />

same time, in group of patients with activity index of kidney<br />

changes (AI) over 4 sVCAM-1 sera levels were significantly<br />

higher comparing group with AI < 4.<br />

Conclusions<br />

Sera level of sVCAM-1 is reliable parameter in evaluation of<br />

autoreactivity degree in SLE. Serial measurements of<br />

sVCAM-1 may be helpful for monitoring disease activity in<br />

patients with SLE and lupus nephritis. The serum level of<br />

sVCAM-1 was correlated with the clinical and histological<br />

activity score. Active lupus nephritis (proliferative lupus<br />

nephritis, WHO classes III and IV) was associated with<br />

significantly elevated sVCAM-1 levels.<br />

References<br />

1. Glandman DD, Urowitz MB. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.<br />

In. Klippel JH, Dieppe PA. Rheumatology, Mosby, London<br />

1998; 7: 11-118<br />

2. Sfikakis PP, Mavrikakis M. Adhesion and lymphocyte<br />

costimulatory molecules in systemic rheumatic disease. Clin<br />

Rheumatol 1999; 18(4): 317-327<br />

3. Sharah SR, Winn R, Harlan J M. The adhesion cascade and<br />

anti-adhesion therapy: An overview. Springer Semin<br />

Immunopathol 1995; 16: 359<br />

4. Gearing AJ, Hemingway I, Pigott R et al. Circulating adhesion<br />

molecules in disease. Immunol Today 1993; 14: 506.<br />

5. Ikeda Y, Fujimoto T, Ameno M et al. Relationship between<br />

lupus nephritis activity and the serum level of soluble VCAM-<br />

1. Lupus 1998; 7: 347-354

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> 2006: 4 (1): 3<br />

Continuous convective renal replacement (CCRR) system: A new modality<br />

of wearable artificial kidney<br />

M.N. Aboras and I.A. Kawalit<br />

Saad Specialist Hospital, Al-Khobar, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia<br />

Abstract<br />

Wearable artificial kidney (WAK) has undergone clinical<br />

trials with results comparable to those of standard<br />

hemodialysis. Although they could have been excellent<br />

programs to rehabilitate End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD)<br />

patients and show them that despite their kidney problems,<br />

they could still enjoy the life. Unfortunately they were<br />

inconvenient due to different reasons, one of which includes<br />

the huge amount of hemofiltration and consequently the<br />

amount of replacement fluids. In this article will present our<br />

design of the WAK that theoretically intended to over come<br />

previous problems.<br />

Key words: hemodialysis, End Stage Renal Disease,<br />

wearable artificial kidney<br />

patients, the feasibility of using continuous hemofiltration in<br />

the regular design, as long-term dialysis program is very<br />

difficult. But the concept of continuous renal replacement<br />

therapy encouraged scientist to develop the wearable model<br />

of artificial kidney.<br />

Although “Wearable artificial kidneys” were intended to be<br />

excellent programs to rehabilitate renal patients and show<br />

them that despite their kidney problems, they could still enjoy<br />

the life. Unfortunately, they were inconvenient due to<br />

different reasons, such as the huge amount of hemofiltration<br />

and consequently the amount of replacement fluids, the<br />

volume of the design, the weight, the vascular access, and<br />

anticoagulation that made the realization of such a design not<br />

feasible.<br />

Diffusive versus Convective transport systems<br />

Introduction<br />

Dialysis as a practical treatment for kidney failure has<br />

evolved over centuries. Many have played a role in<br />

developing this medical technology, starting with Thomas<br />

Graham of Glasgow, who first presented the principles of<br />

solute transport across a semi permeable membrane in 1854<br />

(1). And since then continuous efforts were made to develop<br />

the ideal dialysis machine for patients with End Stage Renal<br />

Disease (ESRD) and while medical technology has made<br />

tremendous strides in treating kidney disease, quality of life<br />

issues and high mortality rates underscore the limitations of<br />

long-term dialysis.<br />

Intermittent Hemodialysis (HD) the most popular treatment<br />

for ESRD consumes about 12 to 15 hours weekly of the<br />

patient’s life during the dialysis sessions. Continuous<br />

Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis (CAPD) is a more<br />

convenient method but it needs special kind of intellectual<br />

and well-educated patients in order to reduce the frequency of<br />

peritonitis episodes. Haemofiltration has been developing<br />

during the last three decades as a possible alternative to the<br />

haemodialysis treatment.<br />

Recent clinical data comparing effective dose delivery by<br />

three acute dialysis therapies: continuous venovenous<br />

hemofiltration (CVVH), daily HD, and sustained lowefficiency<br />

dialysis (SLED), found that effective small solute<br />

clearance in CVVH is 8% and 60% higher than in SLED and<br />

daily HD, respectively. Differences were more pronounced<br />

for middle and large solute categories, the superior middle<br />

and large solute removal for CVVH is due to the powerful<br />

combination of convection and continuous operation (3, 4).<br />

Although it would seem an excellent program for ESRD<br />

______________________<br />

Correspodence to:<br />

Before going over our design we will give a brief description<br />

on the differences between diffusive transport and convective<br />

transport systems to help understand our design of the<br />

Wearable artificial kidney (5-8).<br />

Diffusive transport<br />

Diffusion is the physical phenomenon upon which the<br />

process of hemodialysis depends. It is driven by the<br />

concentration differences between blood and dialysate<br />

compartments and the solutes pass through the<br />

semiperemeable membrane and it is most efficient for the<br />

non-protein bound, low-molecular weight solutes.<br />

Convective transport<br />

In contrast, in the convective therapies, the solvents are<br />

eliminated by solvent drag, secondary to the removal of<br />

plasma water from the blood stream.<br />

Convective transport is more efficient for transport of middle<br />

and high molecular weight non-protein bound molecules,<br />

which can pass through the greater pores in the applied<br />

membranes.<br />

Of course, also the elimination of potentially toxic middle<br />

and high molecular weight molecules could be improved. At<br />

least this has been shown for β 2 micro globulin which might<br />

be involved in arthralgia, carpal tunnel syndrome, neuropathy<br />

and bone disease. Also other molecules, like for instance the<br />

advanced glycation end products (AGEs) (9,10), which<br />

recently have been shown to be associated with<br />

cardiovascular disease, might be eliminated in a more<br />

M.N. Aboras, Saad Specialist Hospital, Al-Khobar, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> 2006: 4 (1): 4<br />

efficient way, as well as inflammatory molecules like<br />

interleukins and endotoxins<br />

Continuous Convective Renal Replacement Therapy as a<br />

Wearable Artificial Kidney<br />

Haemofiltration, being superior to haemodialysis in its<br />

efficacy (5,10), could not be applied as an alternative for<br />

chronic renal failure treatment, due to the huge amounts of<br />

highly purified fluid and electrolytes replacement needed to<br />

be infused intravascularly. We present here our suggested<br />

innovation, which could overcome all the inconveniences of<br />

both haemodialysis and haemofiltration.<br />

Definition<br />

It is a continuous, portable, wearable and disposable renal<br />

replacement therapy system, depending on convective<br />

elimination of water and nitrogenous waist products, which<br />

can be used as a long-term treatment of end-stage renal<br />

failure.<br />

Description<br />

1. Vascular Access:<br />

Is a prerequisite for initiation of the therapy? The most<br />

convenient vascular access modality is Titanium<br />

subcutaneous catheters product of PakuMed® Medical<br />

products gmbh. Two ports are surgically inserted: one in the<br />

central venous system through the right internal jugular vein<br />

or the right subclavian vein, the other is installed in the<br />

arterial system through the right internal jugular or the right<br />

subclavian (innominate artery) Figure 1. (1)<br />

A third Titan Port catheter could optionally be implanted<br />

surgically opposite the suprapubic area, subcutaneously<br />

extending to inside of the urinary bladder.<br />

Fig 1. Graphic design illustrating the Continuous Convective Renal Replacement system<br />

Belt<br />

Arterial line<br />

Hollow fiber<br />

hemofilter<br />

Venous line<br />

Hemofiltrate<br />

collecting bag<br />

The Continuous Convective Renal Replacement system<br />

(Figure 1) is designed in the form of a tight jacket or belt to<br />

be worn by the patient. The material of the jacket can be any<br />

solid, light, leathery non-allergic substance or tissue water<br />

resistant. The jacket extends from the shoulders superiorly<br />

down to the hypogastrium inferiorly. The outside surface of<br />

the jacket is grooved for embedded bloodlines. Two sets of<br />

bloodlines are embedded. Another groove is prepared for the<br />

site of a small haemofilter. On the inside surface, there is two<br />

protruding needles gage 14 to 16, situated opposite the sites<br />

of the Titan Port. These needles are protected with plastic<br />

covers, to be removed at the time of wearing the jacket, and<br />

the needles will puncture the skin opposite the Titan Ports.<br />

In the blood line grooves, are embedded two sets of lines: a<br />

red coded set extending from the arterial needle to the arterial<br />

port of the haemofilter, while the blue coded set extends from<br />

the venous port of the haemofilter to the venous needle. A<br />

third wide bored needle (gage 14) protrudes from the lower<br />

end of the jacket opposite the vesicle Teten Port. This needle<br />

is connected to the ultrafiltration orifice of the haemofilter<br />

through a drainage line.<br />

The whole system of bloodlines, hemofilter and the needles<br />

are primed with heparinized sterile normal saline.<br />

2. The haemofilter:<br />

Is a hollow fiber, or parallel plate dialyser composed of a<br />

high flux, biocompatible membrane. The total surface area,<br />

the porosity, the membrane thickness and the length of the<br />

dialyser are to be calculated to give a rate of hemofiltration is<br />

about 250 ml/hour. Blood inlet and outlet are situated at both<br />

ends of the haemofilter, and a hemofiltrate drainage outlet is<br />

situated on the side of the haemofilter at the arterial end. It’s<br />

connected to either a urine bag or to the vesicle TITAN<br />

PORT.<br />

The whole system is completely sterile and packed in a sterile<br />

elegant package labeled with sufficient information and<br />

instructions about the system usage. A user manual is<br />

included inside the pack.<br />

The driving force of the extracorporeal circulation depends<br />

on the arterio-venous pressure gradient without the use of any<br />

sort of pump or any source of power.<br />

3. Replacement fluid:<br />

In this modality, the replacement fluid is to be given orally to<br />

the patient. Sachets containing salts, replacement materials,

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> 2006: 4 (1): 4<br />

vitamins and sugar are to be prepared. Different formulae of<br />

these sachets are to be prepared according to the nature of the<br />

most common clinical presentations: e.g. those patients who<br />

are salt loosing or salt retaining, those who are usually<br />

acidotic should be given high alkali (sodium bicarbonate)<br />

content and so on.<br />

The patient is to be instructed to dissolve the contents of one<br />

or two sachets in an amount of water to be calculated by his<br />

physician according to the degree of water retention, the<br />

degree of dehydration or over hydration, and the degree of<br />

residual renal function etc…<br />

4. Anticoagulation:<br />

Could be achieved either by an oral anticoagulant<br />

(Coumadine) with adjustment of PT and INR; or low<br />

molecular weight heparin (Clexan) in a prophylactic 12<br />

hourly dose.<br />

Modified design<br />

This model is designed for patient who can’t tolerate large<br />

volume of replacement fluid. It has the same idea of a<br />

continuous, portable, disposable renal replacement therapy<br />

system, it depends on hemofiltration properties (convection)<br />

but, in addition, it has hemodialysis properties (diffusion) and<br />

better control of ultrafiltrate volume and consequently fluid<br />

replacement. This design is techniquely sophisticated.<br />

Description:<br />

The modified design (Figure 2) is divided into three filters;<br />

the first one is a high flux filter will refer to as dialyzer-1,<br />

second one is very low flux filter will refer to as V-filter and<br />

a third one is a low flux-high efficiency filter with dialysate<br />

compartment will refer to as dialyzer-2.<br />

Fig 2.<br />

Dialyzer-1 intended for the medium and large molecular<br />

weight solutes clearance and the V-Filter is used to<br />

ultrafiltrate the drainage from dialyzer-1 to decrease volume<br />

loss (fluid loss), and by doing so the filtrate blood from<br />

dialyzer-1 and the ultafiltrate from the V-Filter will pass to<br />

dialyzer-2 which has a high surface area and small to medium<br />

size pores. Dialyzer-2 has fluid, which act as dialysate fluid<br />

contains removable adsorbent cartilages around its casing bag<br />

to keep the fluid at continuous lower concentration of<br />

diffusible solutes.<br />

The filtrate drainage from the V-Filter, which contains a<br />

concentrated large molecular weight waist solutes with low<br />

volume, will be drained with the drained filtered of the<br />

Dilayzer-2 into a one-way valve urinal bag attached to the<br />

patient’s leg.<br />

In addition, the dialyzer-2 dialysate fluid casing will have a<br />

sensor for the most important diffusible solutes that will<br />

alarm or change in colour to notify the patients to change the<br />

adsorbent cartilage and/or exchange dialysate fluid. Our<br />

intention is to be once daily.<br />

References<br />

1. Graham T. The Bakeries lecture on osmotic force.<br />

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in London.<br />

1854; 144: 177–228<br />

2. Ludger A, Graf H, Prager R et al. Continuous arteriovenous<br />

hemofiltration in the therapy of acute renal insufficiency. Wien<br />

Klin Wochenschr 1984; 6: 96(1): 1-4<br />

3. Liao Z, Zhang W, Hardy PA et al. Kinetic comparison of<br />

different acute dialysis therapies. Artif Organs 2003; 27 (9):<br />

802-7<br />

4. Graham T. The Bakerian lecture—on osmotic force. Philos<br />

Trans R Soc Lond 1854; 144:177–228<br />

5. Bland LA, Favero MS. Microbiologic aspects of hemodialysis<br />

systems. In AAMI Standards and Recommended Practices, vol.<br />

3. Arlington, VA: Association for the Advancement of Medical<br />

Instrumentation 1993; 257–265<br />

6. Daniels F, Alberty RA. Physical Chemistry. New York : John<br />

Wiley& Sons 1955.<br />

7. Gottschalk CW, Fellner SK. History of the science of dialysis.<br />

Am J Nephrol 1997; 17(3-4): 289-98<br />

8. Gerdemann A. Wagner Z, Solf A, et al. Plasma levels of<br />

advanced glycation end products during haemodialysis,<br />

haemodiafiltration and haemofiltration: potential importance of<br />

dialysate quality. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6): 1045-9<br />

9. Lin CL, Huang CC, Yu CC et al. Reduction of advanced<br />

glycation end product levels by on-line hemodiafiltration in<br />

long-term hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 42(3):<br />

524<br />

10. Subramanian, Sanjay; Kellum, John A. Convection of diffusion<br />

in continuous renal replacement therapy for sepsis. Current<br />

Opinion in Critical Care 2000; 6(6): 426-430

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> 2006: 4 (1): 6<br />

Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in dialysis patients<br />

P. Dzekova 1 , A. Slavkovska 2 , L. Simjanovska 2 , I. Nikolov 1 , A. Sikole 1 , R. Grozdanovski 1 , A. Asani 1 , G.<br />

Selim 1 , S. Gelev 1 , V. Amitov 1 , G. Spasovski 1 and M. Polenakovic 1<br />

1 Department of Nephrology, Clinical Center, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia<br />

2 Research Center for genetic engineering and biotechnology, Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Skopje,<br />

Republic of Macedonia<br />

Abstract<br />

Hemodialysis patients are at particularly high risk for<br />

hepatitis C virus infection because of the exposure to blood<br />

products and contaminated equipment. The high prevalence<br />

of HCV infection in dialysis patients is of great concern<br />

because these patients have a higher mortality than HCV<br />

negative patients.<br />

Our study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of HCV infection<br />

among patients at our dialysis unit.<br />

A cohort of 178 patients on maintenance hemodialysis at the<br />

Department of Nephrology, Clinical Center Skopje, was<br />

retrospectively evaluated for the levels of transaminases and<br />

the number of transfused blood products. The presence of<br />

HCV antibodies was determined by second-generation assay<br />

and the presence or absence of HCV RNA in the serum of the<br />

patients was determined by reverse-transcriptase PCR.<br />

The results from this study showed that from 178 patients,<br />

114 (64%) were anti-HCV positive and 64 (36%) were anti-<br />

HCV negative. The duration of dialysis, transaminase levels<br />

and number of transfusions was significantly higher in anti-<br />

HCV positive group of patients when compared with the anti-<br />

HCV negative group.<br />

The high prevalence of anti-HCV positive patients in our<br />

dialysis unit was associated with greater dialysis duration,<br />

blood products transfusions and liver enzyme levels.<br />

Measures to prevent the spread of HCV in dialysis units<br />

should include isolation of HCV RNA positive patients<br />

equipment and possibly their treatment with interferon<br />

therapy.<br />

Key words: hepatitis C virus, prevalence, dialysis patients<br />

Introduction<br />

Hemodialysis patients are at particularly high risk for<br />

hepatitis C (HCV) virus infection because of the exposure to<br />

blood products and contaminated equipment. There is<br />

considerable variation in the prevalence of anti-HCV in<br />

dialysis units worldwide, ranging from as low as 1% to as<br />

high as 63%. Risk factors for spread include a history of<br />

transfusion, number of blood products transfused, and<br />

number of years on hemodialysis therapy (1). The high<br />

prevalence of HCV infection in dialysis patients is of great<br />

concern because these patients have a higher mortality than<br />

HCV negative patients (2). Although HCV transmission<br />

through blood products transfusion previously was a<br />

significant source of infection, current cases are more likely<br />

related to nosocomial exposure (3). Hepatitis C virus is<br />

characterized by spectrum of outcomes. Asymptomatic in the<br />

vast majority of patients, transition from acute to chronic<br />

infection is usually without notice (4,5). In addition to viral<br />

and environmental factors, host genetic and immunological<br />

factors are believed to exert an impact on outcome of HCV<br />

infection (6). The mechanisms involved in viral clearance are<br />

not yet fully understood, although increasing evidence<br />

suggests that cellular immune responses to HCV play a<br />

central role (7). The aim of this study was to evaluate the<br />

prevalence of HCV infection among patients at our dialysis<br />

unit.<br />

Patients and Methods<br />

The study was carried on 178 (113 men) patients on<br />

maintenance hemodialysis at the Department of Nephrology,<br />

Clinical Center, Skopje. The mean age of patients was 54.8<br />

years and mean time on dialysis 86 months. The levels of<br />

liver aminotransferase enzymes: alanine aminotransferase<br />

(ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and the number<br />

of transfused blood products, were recorded from the<br />

histories of the patients. The presence of HCV antibodies was<br />

determined by second-generation assay. The presence or<br />

absence of HCV RNA in the serum of the patients was<br />

determined by reverse-transcriptase PCR (RT/PCR) at<br />

Research Center for genetic engineering and biotechnology,<br />

Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Skopje.<br />

Student’s t-test was used for group mean comparison<br />

between anti-HCV positive and anti-HCV negative patients.<br />

Results<br />

Fig 1. Distribution of anti-HCV positive and anti-HCV<br />

negative patients in the study<br />

anti-HCV -<br />

64(36%)<br />

anti-HCV + anti-HCV -<br />

anti-HCV +<br />

114 (64%)<br />

The results from this study showed that from 178 patients,<br />

114 (64%) were anti-HCV positive and 64 (36%) were anti-<br />

______________________<br />

Correspodence to: P. Dzekova, Department of Nephrology, Clinical Center Skopje, Medical Faculty,<br />

University "Sts. Cyril and Methodius", Republic of Macedonia

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> 2006: 4 (1): 7<br />

HCV negative (Figure.1).<br />

The mean values of age, duration on dialysis, levels of AST<br />

and ALT, and number of transfusions in anti-HCV positive<br />

and anti-HCV negative patients, and comparison between<br />

them are given in Table 1.<br />

Table 1. Mean values of age, duration on dialysis, levels of AST and ALT, and number of transfusions, and<br />

comparison between anti-HCV positive and anti-HCV negative patients<br />

anti-HCV positive anti-HCV negative p value<br />

age (years) 53.81 ± 13.61 56.62 ± 12.06 NS<br />

duration (months) 103.7 ± 71.6 53.41 ±33.7 0.00<br />

AST (U/L) 37.87 ± 21.96 23.05 ±11.63 0.00<br />

ALT (U/L) 53.74 ± 34.71 25.06 ± 14.05 0.00<br />

No. of transfusions 8.91 ± 13.53 4.84 ± 5.27 0.03<br />

The duration of dialysis in months was significantly longer in<br />

anti-HCV positive than in anti-HCV negative patients (103<br />

vs. 53, p

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> 2006: 4 (1): 8<br />

Influence of inflammation on nutritional status of dialysis patients<br />

P. Dzekova, I. Nikolov, G. Severova-Andreevska, A. Sikole, R. Grozdanovski, A. Asani, G. Selim,<br />

S. Gelev, V. Amitov, G. Spasovski and M. Polenakovic<br />

Department of Nephrology, Clinical Center Skopje, Medical Faculty, University Sts Cyril and Methodius, Republic of Macedonia<br />

Abstract<br />

Malnutrition and inflammation are frequently observed in<br />

maintenance hemodialysis patients as risk factors for poor<br />

quality of life and increased morbidity and mortality. The<br />

causes and consequences of both are anorexia,<br />

hypoalbuminemia, muscle wasting, refractory anemia, and,<br />

possibly accelerated arteriosclerosis.<br />

The aim of our study was to evaluate the influence of<br />

inflammation on parameters of nutritional status dialysis<br />

patients at the Department of Nephrology, Clinical Center<br />

Skopje.<br />

We crossectionally analysed 154 dialysis patients (93 men)<br />

which were then followed in a period of six consecutive<br />

months. A number of biochemical and anthropometrical<br />

parameters were evaluated as measures of nutritional status.<br />

The mean (±SD) age of all patients was 54.8 ± 12.7 years and<br />

vintage (duration of dialysis therapy) from 7 to 288 months.<br />

CRP and serum albumin levels were significantly greater in<br />

men than in women (12.9 vs. 7.97, p < 0.04 and 40.2 vs. 38.8,<br />

p < 0.02, respectively). Triceps skin fold, mid arm<br />

circumference and body mass index measurements were<br />

statistically greater in women than in men (p < 0.01). CRP<br />

level strongly correlated only with serum concentration of<br />

cholesterol (r =0.49, p

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> 2006: 4 (1): p 9<br />

Results<br />

Our results showed that CRP level was significantly greater<br />

in men than in women (12.9 vs. 7.97, p < 0.04). Serum<br />

albumin level was significantly greater in men than in women<br />

(40.2 vs. 38.8, p < 0.02). Serum cholesterol level tended to be<br />

greater in men than in women (p=NS). Triceps skin fold<br />

measurements were statistically greater in women than in<br />

men (1.37 vs. 0.96, p < 0.001). Mid arm circumference and<br />

body mass index were greater in women, whereas mid arm<br />

muscle circumference was greater in men, but not statistically<br />

(Table 1).<br />

Table 1. Laboratory and anthropometrical data, and a comparison<br />

between men and women<br />

men women p<<br />

No. of patients 93 61<br />

CRP (mg/l) 12.9 ±16.9 7.97 ± 10.9 0.04<br />

albumin (g/l) 40.2 ±4.0 38.8 ± 3.7 0.02<br />

cholesterol<br />

(mmol/L) 3.7 ± 1.4 3.2 ± 1.5 NS<br />

TSF (cm) 0.96 ±0.3 1.37 ± 0.6 0.0001<br />

MAC (cm) 26.3 ± 2.7 27.3 ± 4.4 NS<br />

MAMC (cm) 23.27 ± 3.1 23.03 ± 3.5 NS<br />

BMI (kg/m2) 23.03 ± 3.2 23.7 ± 4.7 NS<br />

CRP level showed strong correlation only with serum<br />

concentration of cholesterol (r =0.49, p

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> 2006: 4 (1): p 10<br />

Unfavorable prognostic factors in Immunoglobulin A Nephropathy<br />

L. Petrovic, S. Curic, I. Mitic, D. Bozic, S. Vodopivec, V. Sakac, T. Djurdjevic-Mirkovic and T. Ilic<br />

Clinical Centar Novi Sad, Clinic for Nephrology and Clinical Immunology, Novi Sad, Serbia and Montenegro<br />

Abstract<br />

Immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) is a<br />

clinicopathological entity characterized by diffuse glomerular<br />

mesangial deposition of IgA as the predominant<br />

immunoglobulin. Renal biopsy reveals a spectrum of changes<br />

in the glomerul, tubulointerstitium and blood vessels. 20-50%<br />

of all patients develope end-stage renal failure 20 years after<br />

onset of the disease.<br />

The aim of this stady was to analized influence of<br />

clinicopathological and laboratory changes to prognosis of<br />

IgAN. The study included 60 patients with biopsy-proven<br />

IgAN without some other systemic diseases or purpura<br />

Henoch-Schnlein. We analized influence of clinical features<br />

of the disease, laboratory and immunofluorescence/light<br />

microscopy findings on the prognosis of IgAN. The study<br />

was partly retrospective and partly prospective. At the<br />

moment of renal biopsy 63,16% of patients had normal renal<br />

function, 31,58% had stage I and 5,25% had stage II chronic<br />

renal failure. At the end of study 21,05% of investigated<br />

patients progressed to a worse stage of renal failure with<br />

regard to the initial stage.<br />

In this study we found severe histopathological changes in<br />

the group with already impaired renal function and these<br />

changes correlated with laboratory findings, clinical features<br />

and prognosis of the disease. Normal renal function at the<br />

moment of renal biopsy provides smaller risk of further<br />

damage. Changes in the tubulointerstitium, mesangium,<br />

heavy proteinuria and hypertension influence to worse<br />

prognosis of disease. Crossing to the higher stage of renal<br />

failure was 1,24% per year and this requires long-term<br />

follow-up of patients with IgAN.<br />

Key words: IgA nephropathy, renal biopsy, outcome<br />

Introduction<br />

Immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN), immunoglobulin A<br />

glomerulonephritis (IgAGN) or Berger’s disease is a special<br />

clinical/pathological entity which is characterized by the<br />

finding of immunofluorescent microscopy with predominant<br />

IgA deposits in mesangium of the glomerul.<br />

Morphological characteristics of the nephrotic damages in<br />

IgAN, similarly to clinical manifestation of the disease, are of<br />

a different form and degree of attack on glomerul, tubule,<br />

interstitium and blood vessels. Clinical progress of the<br />

disease is in correlation with histopathological changes with<br />

existence of significant clinical/pathological correlation with<br />

disease prognosis (1,2). Clinical and histopathological<br />

indicators (present at the moment of diagnosis) of the<br />

unfavorable disease prognosis are: 1) older age, 2) male sex,<br />

3) absence of episodes of macrohematuria, 4) lower intensity<br />

value of glomerular filtration (IGF), 5) heavier proteinuria<br />

(>1000mg/24h) or proteinuria of nephrotic rank, 6) arterial<br />

hypertension, 7) more pronounced histopathological changes,<br />

8) intensive IgA and C3 immunofluorescent deposits in<br />

glomerul and capillary wall, commonly associated with IgG<br />

deposits and fibrinogen are also considered to be the markers<br />

of unfavorable prognosis, 9) as the independent factors of the<br />

unfavorable disease prognosis, one can account for diabetes<br />

mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia, hyperuricemia, period of<br />

disease duration, positive family history (3-8).<br />

IgA nephropathy was firstly called benign recurrent<br />

hematuria, however, a long-term follow-up of the renal<br />

function has shown that IgAN represents a slow, progressive<br />

illness of a different result which includes a high incidence of<br />

progressive damage of renal function with development of<br />

terminal nephritic insufficiency in 20-50% of the diseased, 20<br />

years after the beginning of the disease. The research has<br />

shown that the damage of the renal function is developed<br />

faster in patients with an initial impairment of renal function,<br />

in contrast to patients with relatively normal renal function at<br />

diagnosis (4,6). The most significant prognostic factors in<br />

IgA nephropathy are histopathological changes, so that the<br />

expressed mesangial proliferation, glomerulosclerosis,<br />

presence of crescent formations, arteriosclerosis, interstitial<br />

fibrosis represent histological markers of unfavorable<br />

prognosis. Glomerulosclerosis, focal-segmented and<br />

especially diffuse, influence renal function substantially more<br />

intensively than the proliferative changes. Tubulointerstitial<br />

infiltrate, especially T cellular (CD4+, CD8+) is in<br />

correlation with faster progression of the disease. Interstitial<br />

fibrosis, regardless of simultaneous presence or absence of<br />

glomerulosclerosis, is also a significant prognostic factor.<br />

This explains different rate of renal function damaging in<br />

patients with the same level of glomerular damage, but<br />

different considering the tubulointerstitial inflammatory<br />

infiltrate or sclerosis (1,3,6,9,10).<br />

The aim of this study was to analyze the influence of clinicalpathological<br />

and laboratory changes on prognosis of IgAN.<br />

Considering the possibility of development and progression<br />

of chronic renal insufficiency, the justification of longer<br />

follow-up of the diseased was reviewed.<br />

Patients and methods<br />

Testing covered 60 patients, who had percutaneous renal<br />

biopsy at the Clinic of Nephrology and Clinical Immunology<br />

of Clinical Center Novi Sad. The tested patients had<br />

documentation which consisted of at least, the first control<br />

______________________<br />

Correspodence to: L. Petrovic, Clinical Centar Novi Sad, Clinic for Nephrology and Clinical Immunology,<br />

Novi Sad, Serbia and Montenegro

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>2006: 4 (1): p 11<br />

examination, i.e. they were followed-up for at least one<br />

month up to maximum 17 years. Criterion for inclusion into<br />

the study was the finding of IgA deposits, as a dominant<br />

immunoglobulin in the mesangium of glomerul, which was<br />

deduced by immunofluorescent microscopy, while the<br />

presence of Henoch-Schonlein purpura and some other<br />

systematic illness were excluded.<br />

Immunohistological technique included the application of<br />

standard antiserums: anti-IgA, -IgG, -IgM, -C3, -C4, -C1q, -<br />

fibrin. The intensity of positive immunofluorescent finding<br />

was estimated semi-quantitatively with a precise localization<br />

of the deposits.<br />

Results<br />

Patients’ age ranged from 14-56 years, with an average of<br />

34.19 years. From the cohort of 60 patients, 70% were of<br />

male sex, while 30% of them were female.<br />

At the moment of renal biopsy, i.e. the diagnostics of the<br />

disease, 36 patients (63.16%) had a normal renal function<br />

(creatinine < 107 mol/l, clearance creatinine > 90<br />

ml/min/m 2 ), 18 patients (31.58%) were in stadium I of renal<br />

insufficiency (creatinine < 133 mol/l, clearance of creatinine<br />

60-90 ml/min/m 2 ) and 3 patients (5.26%) were in stadium II<br />

of renal insufficiency (creatinine 133-440 mol/L, clearance<br />

of creatinine 10-60 ml/min/m 2 ). Out of 36 patients, who at<br />

the moment of diagnostics had normal renal function, 31<br />

patient (86,11%) preserved the renal function until the end of<br />

the follow-up, 5 patients (13,89%) moved to stadium I of<br />

renal insufficiency. 12 patients (66.67%) from the group of<br />

18 patients with initial stadium I of renal insufficiency<br />

remained in this stadium, while 6 patients (33.33%) moved to<br />

stadium II. 2 patients (66.67%) from the group of 3 patients<br />

with initial stadium II remained in this stadium, while 1<br />

patient (33.37%) moved to stadium III.<br />

If we observe the total number of patients who moved from<br />

one stadium of renal insufficiency to another (0I, III,<br />

IIIII), their total number was 12 (21.05%) for the follow-up<br />

period of 17 years, i.e. 1.24% of patients annually moved to a<br />

higher stadium in relation to the initial renal function (Table<br />

1).<br />

Table 1. Relationship between beginning and end stage renal failure<br />

Beginning<br />

stage<br />

Normal<br />

function<br />

Number<br />

Percent<br />

36 63,16 %<br />

Stage of renal function at the<br />

end of the study<br />

Number<br />

Percent<br />

Normal function 31 86,11%<br />

I stage of renal failure 5 13,89%<br />

I stage of<br />

renal<br />

failure<br />

II stage of<br />

renal<br />

failure<br />

18 31,58 %<br />

3 5,26 %<br />

I stage of renal failure 12 16,67%<br />

II stage of renal failure 6 33,33%<br />

II stage of renal failure 2 66,67%<br />

III stage of renal failure 1 33,37%<br />

57 100 % 57 100%<br />

Within the group of patients with normal initial renal<br />

function, the existence of positive correlation was identified<br />

among: 1) changes in mesangium and increase of creatinine<br />

concentration, 2) changes in mesangium and appearance of<br />

microhematuria in clinical manifestation of the disease, 3)<br />

glomerulosclerosis and higher values of systolic blood<br />

pressure, 4) crescent formations and severity of proteinuria<br />

(Table 2).<br />

Table 2. Positive correlation between pathological findings with<br />

clinical features and laboratory parameters in the group of patients<br />

with normal renal function at the beginning<br />

Pathological<br />

Degree of<br />

Laboratory findings<br />

findings<br />

correlation<br />

Creatinine concentraction<br />

Mesangium increase<br />

r=0,47<br />

Microhematuria<br />

r=0,35<br />

Glomerulosclerosis Systolic blood presure r=0,21<br />

Crescent Proteinuria r=0,24<br />

The conclusions of the testing of patients with the initial<br />

stadium I renal insufficiency are the following: 1) there is an<br />

easy connection of changes in mesangium with the increase<br />

of creatinine concentration, higher values of systolic and<br />

diastolic blood pressure, 2) there is a significant correlation<br />

of glomerulosclerosis with microhematuria and heavier<br />

proteinuria, 3) there is an easy correlation between the<br />

presence of crescent formations and heavier proteinuria, 4)<br />

the changes in interstitium are in correlation with systolic,<br />

diastolic blood pressure and heavier proteinuria, 5) the<br />

changes in tubule are in easy correlation with a heavier<br />

proteinuria and the appearance of microhematuria (Table 3).<br />

Table 3. Positive correlation between pathological findings with<br />

clinical features and laboratory parameters in the group of patients<br />

with Ist stage of renal failure<br />

Pathological<br />

findings<br />

Laboratory findings<br />

Degree of<br />

correlation<br />

Creatinine concentration<br />

increase<br />

r=0,30<br />

Mesangium Systolic blood pressure r=0,37<br />

Diastolic blood pressure r=0,31<br />

Glomerulosclerosis Proteinuria r=0,35<br />

Microhematuria<br />

r=0,66<br />

Crescent Proteinuria r=0,35<br />

Proteinuria<br />

r=0,71<br />

Intestitium Systolic blood pressure r=0,39<br />

Diastolic blood pressure r=0,35<br />

Tubulus<br />

Proteinuria<br />

r=0,33<br />

Microhematuria<br />

r=0,25

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>2006: 4 (1): p 12<br />

Conclusions<br />

In this study, we found severe histopathological changes in<br />

the group with already impaired renal function and these<br />

changes correlated with laboratory findings, clinical features<br />

and prognosis of disease. Normal renal function at the<br />

moment of renal biopsy provides smaller risk of further<br />

damage. Changes in the tubulointerstitium, mesangium,<br />

heavy proteinuria and hypertension influence the worsening<br />

of prognosis of the disease. Crossing to the higher stage of<br />

renal failure was 1.24% per year and this requires a long-term<br />

follow-up of patients with IgAN.<br />

References<br />

1. Amico GD. Natural history of idiopathic IgA nephropathy: role<br />

of clinical and histological prognostic factors. Am J Kidney Dis<br />

2000; 36 (2): 227-37<br />

2. Droz D. IgA nephropathy: clinicopathologic correlations. In:<br />

Clarkson A. IgA Nephropathy. Martinus Nijhoff Publishing,<br />

Boston 1987; 97-101<br />

3. Wyatt RJ, Kritchevsky SB, Woodford SY et al. IgA<br />

nephropathy: long-term prognosis for pediatric patients. J<br />

Pediatr 1995; 127 (6): 913-919<br />

4. Ibels LS, Gyory AZ. IgAN: analysis of the natural history,<br />

important factors in the progression of of renal disease, and<br />

review of the literature. Medicine-Baltimore 1994; 73(2): 79-<br />

102<br />

5. Droz D. IgA nephropathy: clinicopathologic correlations. In:<br />

Clarkson A. IgA Nephropathy. Martinus Nijhoff Publishing,<br />

Boston, 1987; 101-102<br />

6. Donadio JV, Bergstra EJ, KP. Offord et al. Clinical and<br />

histopathologic associations with impaired renal function in<br />

IgAN. Clin Nephrol 1994; 41(2): 65-71<br />

7. Kenji W, Shigene N, Seicli M et al. Risk Factors for IgA<br />

Nephropathy: A Case-Control Study with Incident Cases in<br />

Japan. Nephron 2002; 90(1): 16-23<br />

8. Mustonen J, Syrjanen J, Rantala I et al. A. Clinical course and<br />

treatment of IgA nephropathy. J Nephrol 2001; 14: 440-446<br />

9. Alexopoulos E, Papaghianni A, Papadimitriou M. The<br />

pathogenetic significance of C5b-9 in IgA nephropathy.<br />

Nephrol Dial Transplant 1995; 10(7): 1166-72<br />

10. Daniel L, Saingra Y, Giorgi R et al. Tubular lesions determine<br />

prognosis of IgA nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis 2000; 35(1):<br />

13-20

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>2006: 4 (1): p 13<br />

Congestive heart failure and renal dysfunction<br />

D. Monova 1 , E. Peneva 1 and S. Monov 2<br />

Department of Internal Diseases, Medical Institute 1 – MIA, Medical University 2 , Sofia, Bulgaria<br />

Abstract<br />

The kidney plays a key role in the homeostatic maintenance<br />

of fluids and electrolytes in the context of chronic congestive<br />

heart failure (CHF). CHF carries a spectrum of<br />

pathophysiological aberrations, which constitute a stress on<br />

the respective renal regulatory mechanisms.<br />

We defined bedside clinical, laboratory and<br />

electrocardiographic parameters characterizing CHF patients<br />

with and without concomitant renal failure (RF), and<br />

analyzed their impact on mortality. We studied 146<br />

symptomatic unselected consecutive furosemide-treated CHF<br />

patients hospitalized for various acute conditions. On<br />

admission, history taking, physical examination, chest x-ray,<br />

ECG and routine laboratory tests were performed.<br />

Subsequently, patients were divided into 2 subgroups, those<br />

with serum creatinine > 140 µmol/l (58) and those with<br />

lower values (88). Prevailing in RF subgroup were older age,<br />

male gender, admission pulmonary edema, cardiac<br />

arrhythmias, cardiac condition disturbances, lower ejection<br />

fraction, anemia, higher furosemide maintenance dosages,<br />

insulin treatment and receiving less ACE inhibitors. RF being<br />

the parameter most significantly associated with low survival.<br />

Using multivariate analysis in the RF subgroup, older age,<br />

female gender and diabetes mellitus proved most<br />

significantly associated with poorer survival. In the non-RF<br />

subgroup, only older age and diabetes mellitus were<br />

significantly associated with low survival.<br />

Renal failure is a marker of severity in CHF. Its full-blown<br />

deleterious prognostic effect is already manifested at serum<br />

creatinine 140 µmol/l. Older age, diabetes mellitus and<br />

female gender significantly heralded a shorter survival. Such<br />

patients require special care.<br />

Key words: congestive heart failure, renal failure, diabetes<br />

mellitus, gender, age<br />

Introduction<br />

The kidney plays a key role in the homeostatic maintenance<br />

of fluids and electrolytes in the context of chronic congestive<br />

heart failure (CHF)(1). CHF carries a spectrum of<br />

pathophysiological aberrations, which constitute a stress on<br />

the respective renal regulatory mechanisms. It has been<br />

shown that the presence of renal failure in patients with<br />

congestive heart failure is associated with shorter survival (2-<br />

4). Moreover, renal failure, even moderate, represents not<br />

only a marker for poor prognosis, but also an independent<br />

risk factor for increased mortality (3).<br />

We defined bedside clinical, laboratory and<br />

electrocardiographic parameters, characterizing CHF patients<br />

with and without concomitant renal failure (RF), and<br />

analyzed their impact on mortality.<br />

Patients and methods<br />

We studied 146 symptomatic unselected furosemide-treated<br />

patients with congestive heart failure, hospitalized for various<br />

acute conditions. Congestive heart failure was of various<br />

etiologies and had been present for at least 6 months prior to<br />

admission. All patients had been on chronic furosemide<br />

treatments of at least 40 mg/day for more than 3 months.<br />

On admission, blood was drawn for serum biochemical<br />

determinations, including glucose, creatinine, chloride,<br />

potassium, sodium, bicarbonate, blood pH, calcium,<br />

phosphorus, cholesterol, triglycerides and blood count. All<br />

determinations were performed using conventional methods.<br />

The history taking, physical examination, chest x-ray and<br />

ECG were performed. Subsequently, patients were divided<br />

into 2 subgroups, those with serum creatinine > 140 µmol/l<br />

(58 patients) and those with lower values (88 patients).<br />

Results and discussion<br />

The study group included 146 patients (84 females and 62<br />

males, mean (±SD) age 71,4±19,6 years). Renal failure was<br />

present in 58 (39,73%) patients. Table 1 depicts the mean<br />

values of quantitative variables in the patients with renal<br />

failure as compared to those with normal creatinine values.<br />

Table 1. Mean values of quantitative variables in congestive heart<br />

failure patients with versus without renal failure<br />

Characteristic<br />

Patients with Patients without<br />

renal failure renal failure<br />

Weight (kg) 68,7±12,4 70,4±13,6<br />

Age (years) 65,4±6,4 60,3±8,3<br />

Serum potassium 4,71±0,82 4,5±0,52<br />

(mmol/l)<br />

Serum bicarbonate 24,4±4,22 26,24±3,96<br />

(mmol/l)<br />

Serum chloride<br />

104,0±5,4 102,88±4,6<br />

(mmol/l)<br />

Serum phosphorous 3,8±0,8 3,5±0,5<br />

(mmol/l)<br />

Blood pH 7,37±0,06 7,39±0,05<br />

It can be seen that patients with renal failure were<br />

significantly older (P

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> 2006: 4 (1): p 14<br />

Table 2. Qualitative variables prevailing in congestive heart failure<br />

patients with versus without renal failure<br />

Characteristic<br />

Patients with<br />

renal failure<br />

- N(%)<br />

Patients<br />

without renal<br />

failure – N(%)<br />

Male gender 37 (63,79%) 25 (28,41%)<br />

Pulmonary edema on<br />

admission<br />

36 (62,07%) 29 (32,95%)<br />

Cardiac arrhythmias on<br />

34 (58,62%) 28 (31,82%)<br />

admission<br />

NYHA class III-IV 35 (60,34%) 31 (35,23%)<br />

Ejection fraction < 30% 25 (43,10%) 15 (17,04%)<br />

Presence of anaemia 30 (51,72%) 20 (22,73%)<br />

Furosemide dosage>80mg 20 (34,48%) 10 (11,36%)<br />

Treatment with ACE<br />

inhibitors<br />

28 (48,28%) 59 (67,04%)<br />

Male gender, admission pulmonary edema, cardiac<br />

arrhythmias (atrial or ventricular premature beats >6 min,<br />

couplets, atrial fibrillation, supraventricular or ventricular<br />

tachycardia), severe CHF, lower ejection fraction, anemia,<br />

higher furosemide maintenance dosages and receiving less<br />

ACE inhibitors prevailed in the subgroup with renal failure.<br />

Duration of furosemide treatment, presence of hypertension,<br />

periferal vascular disease, ischemic heart disease, chronic<br />

obstructive pulmonary disease, hypokalemia or hyponatremia<br />

on admission, treatment with calcium channel blockers,<br />

nitrates or digoxin, were not significantly different between<br />

the two subgroups.<br />

The follow-up period extended up to 40 months, median<br />

34±12 months. During this period 24 (16,44%) patients died.<br />

17 patients (70,83%) were from subgroup with renal failure.<br />

Renal failure was the parameter most significantly associated<br />

with low survival. Using multivariate analysis in the<br />

subgroup with renal failure, older age, severity of CHF,<br />

female gender proved to be significantly associated with<br />

poorer survival. In the subgroup without renal failure, only<br />

older age was significantly associated with low survival.<br />

Parameters which did not influence survival in the subgroup<br />

with renal failure, included duration of furosemide treatment,<br />

hypertension, hyperlipidemia, anaemia, various cardiac<br />

arrhythmias, use of vasodilators or digoxin and hypokalemia<br />

or hyponatremia on admission.<br />

The pathophysiological interrelationship between CHF and<br />

renal insufficiency is bidirectional, involving a variety of<br />

factors (1). Activation of the neurohormonal and reninangiotensin<br />

systems, mainly via reduction of effective blood<br />

volume in CHF leads to stimulation of aldosterone and ADH<br />

secretion. These may produce a rise in cardiac filling<br />

pressure, increased extracelular volume, edema and organ<br />

dysfunction, including deterioration of CHF. Within the<br />

context of the kidney, intravascular volume depletion and the<br />

ensuing GFR reduction, eventually limit natriuresis and<br />

diuretic capacity despite enhanced nitric oxide production<br />

and activation of natriuretic substances. Superposition of<br />

renal failure on CHF implies an additional burden of poor<br />

prognostic factors. These may include various electrolite and<br />

acid-base balance aberrations, decreased immunological<br />

competence, osteoporosis, enhanced bleeding tendency and<br />

other factors, which may shorten survival from cardiac and<br />

non-cardiac death (5).<br />

Conclusions<br />

Renal failure is a marker of severity in CHF. Its full-blown<br />

deleterious prognostic effect is already manifested at serum<br />

creatinine of 140 µmol/l. Older age and a female gender<br />

significantly heralded a shorter survival. We were unable to<br />

find such association in the literature (3). Such patients<br />

require special care. Following discharge, patients were<br />

managed exclusively by their primary physicians. Therefore<br />

our results are not biased by other factors such as those<br />

introduced by pharmaceutically oriented studies or those<br />

involving intervention by specialized heart failure clinics.<br />

References<br />

1. Zanchetti, A and Stella A. Cardiovascular disease and the<br />

kidney: an epidemiologic overview. – J Cardiovasc. Pharmacol<br />

1999; 33, 1-6<br />

2. Al-Ahmad, Rand WM, Manjundth G et al. Reduced kidney<br />

function and anemia as risk factors for mortality in patients<br />

with left ventricular dysfunction. – J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;<br />

38: 955-962<br />

3. Dries DL, Exner DV, Domanski MJ et al. The prognostic<br />

implications of renal insufficiency in asymptomatic and<br />

symptomatic patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction.<br />

– J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35: 681-689<br />

4. Mosterd A, Cast B, Hoes AW et al. The prognosis of heart<br />

failure in the general population: The Rotterdam Study - Eur<br />

Heart J 2001; 22: 1318-1327<br />

5. Muntner P, Hamm L, Lorid C et al. Renal insufficiency and<br />

subsequent death resulting from cardiovascular disease in the<br />

United States. – J Am Soc Nephrol 2002; 13: 745-75

<strong>BANTAO</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> 2006: 4 (1): p 15<br />

Sporadic Balkan Endemic Nephropathy (BEN) beyond the known regions of<br />

BEN<br />

J. Nikolic¹, T. Pejcic¹, D. Crnomarkovic¹, Z. Gavrilovic² and C. Tulic¹<br />

¹Urologic Clinic-Faculty of Medicine Belgrade, ² Institute for developement of water resources, Jaroslav Cerni,<br />

Belgrade, Serbia and Montenegro<br />

Abstract<br />

There is an very old opinion that we diagnose only most<br />

prominent BEN cases and miss latent and mild ones, that<br />

unrecognized BEN is possible in endemic villages and the<br />

number of such cases, their characteristics, and origin are<br />

unknown.<br />

From 1955 to 1998 year we evaluated 1235 patients with<br />

histologicaly proven upper urothelial tumors, who underwent<br />

surgery. The diagnosis of sporadic BEN, was made after<br />

exclusion of other known nephropaties.<br />