When Caitlin, 35, met Jilly, 73⦠- Press Awards

When Caitlin, 35, met Jilly, 73⦠- Press Awards

When Caitlin, 35, met Jilly, 73⦠- Press Awards

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

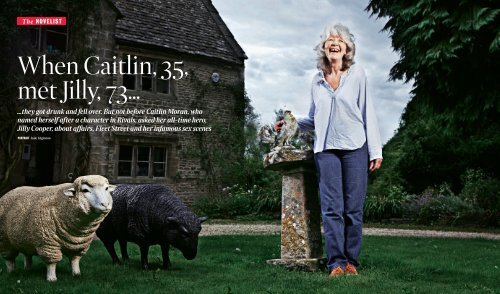

The NOVELIST<br />

<strong>When</strong> <strong>Caitlin</strong>, <strong>35</strong>,<br />

<strong>met</strong> <strong>Jilly</strong>, 73…<br />

…they got drunk and fell over. But not before <strong>Caitlin</strong> Moran, who<br />

named herself after a character in Rivals, asked her all-time hero,<br />

<strong>Jilly</strong> Cooper, about affairs, Fleet Street and her infamous sex scenes<br />

PORTRAIT Jude Edginton<br />

36<br />

PAGE XX 11 September 2010<br />

11 September 2010<br />

ttm11036 1-2 06/09/2010 12:20<br />

PAGE 37

This is where Rupert<br />

Campbell-Black was<br />

playing tennis, naked,<br />

when he first meets<br />

Taggie,” <strong>Jilly</strong> Cooper says.<br />

It’s an overcast day<br />

in Gloucestershire, and<br />

we’re standing on a soggy<br />

lawn, taking a tour of<br />

Cooper’s wisteria-fringed house and gardens.<br />

She is holding a bottle of champagne.<br />

Our glasses are half-full. We’re both a bit<br />

staggery: we’ve been on the sauce since<br />

1pm, didn’t bother much with lunch, and it’s<br />

now gone four. I’ve missed two trains, urged<br />

to ignore their departure by Cooper howling,<br />

“Oh, do stay. We need more gossip!”<br />

On our way down the hall, Cooper<br />

bumps gently off the wall. “Whoops!” she<br />

hoots, veering to the left, then bumping<br />

off the opposite wall. “I’m a bit tight!”<br />

We are combining the “more gossip”<br />

with sightseeing around Cooper’s grounds,<br />

which double – as anyone who has read her<br />

legendarily filthy novels will know – as<br />

the setting for her fictional “Rutshire” canon.<br />

Cooper’s house is Rupert Campbell-Black’s.<br />

To the right is the Bluebell Wood, where<br />

Billy first rolled around with Janey in the<br />

wet nettles. And this tennis court is, indeed,<br />

where Campbell-Black – for many women,<br />

a literary hero the equal of Mr Darcy – played<br />

mixed doubles in the knack. (“Cock fault! You<br />

must be at least ten inches over the line!”)<br />

I am, essentially, being given a dirty tour<br />

of Bath by a pissed Jane Austen.<br />

As this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,<br />

I feel I must tell Cooper my thesis on her<br />

legendary output. I’ve long had the theory<br />

that Riders – the incendiary 1985 book that<br />

launched the whole Rutshire series; current<br />

sales: more than 15 million – must have been<br />

the result of a blazing hot affair. Cooper had<br />

just moved from London to Gloucestershire,<br />

and fallen in with a set – Andrew Parker<br />

Bowles; Michael, Earl of Suffolk; Rupert<br />

Lycett Green; the Duke of Beaufort – that she,<br />

in later years, described as “wildly dashing and<br />

exciting”. Indeed, in 2002, she admitted that<br />

swaggering, sexy Campbell-Black was<br />

conceived as an amalgam of all four of them.<br />

She must have been shagging one of<br />

them, I surmised. Riders is a book written by<br />

someone ablaze with desire – written with the<br />

born-again ardour of someone coming alive<br />

for the second time. Come on! It’s obvious!<br />

“Were you having an affair?” I ask her,<br />

gently wobbling in the breeze. There is a<br />

pause. Cooper looks out across the pale,<br />

rainy valley – she’s now 73, but with the same<br />

pale fluff of hair and fox-like eyes she had<br />

at <strong>35</strong>, when she was the hot young Sunday<br />

Times columnist, racketing around Fleet<br />

Street in a miniskirt, playing table tennis<br />

‘People weren’t worried<br />

about sex. We had<br />

contraception, no Aids.<br />

It was joyful, exploratory’<br />

with Melvyn Bragg in a see-through dress,<br />

and kissing Sean Connery in the hallway.<br />

“I just fell in love with the countryside,”<br />

Cooper says, eventually, looking out across<br />

the landscape. “That was what made me come<br />

alive. I was having an affair with the whole of<br />

the Cotswolds. Leo [her husband] stayed in<br />

London at the time, and I moved here, and<br />

everyone said: ‘Oh, if you move to the country,<br />

you’ll get in trouble.’ But I never did. It was<br />

the impact of the country. The liberation.”<br />

We stand in the rain a while, looking at<br />

the wet beeches. Then Cooper looks down<br />

at the champagne bottle in her hand. “Oh,<br />

it’s empty,” she says, disconsolately. There<br />

is a pause. Then: “We must open another!”<br />

For a generation of women – my generation<br />

– <strong>Jilly</strong> Cooper is totemic: a combination of<br />

role model and storyteller who made being<br />

As a Sunday Times<br />

writer in the Seventies<br />

The NOVELIST<br />

a woman seem like fun. Her columns<br />

in The Sunday Times were, at the time,<br />

revolutionary: the novel ruse of getting<br />

a woman to write humorously about<br />

her domestic, <strong>met</strong>ropolitan life.<br />

She goes to jumble sales, walks the<br />

dogs, gets squiffy at dinner parties, gets<br />

squiffy on sports day, boggles over the newly<br />

published Hite Report (“The <strong>met</strong>hod of orgasm<br />

achievement is rather quaint: ‘I bang my mons<br />

against the sink,’ said one housewife”), frets<br />

about her weight (“Who wants to be 8st 5<br />

if they look like a flat-chested weasel?”), finds<br />

out she’s infertile and adopts two children<br />

with breezy can-do-ness, and confesses<br />

all of her most inappropriate thoughts (“One<br />

of the compensations of getting old is flirting<br />

with friends’ offspring. I quite fancy myself<br />

as the ‘close bosom friend of a maturing<br />

son’”) with both self-deprecation and a<br />

winning, underlying confidence. Ultimately,<br />

she doesn’t really care what anyone thinks,<br />

because she’s having such a hoot.<br />

Where all the female columnists of the<br />

21st century – and, indeed, eventually, Helen<br />

Fielding’s Bridget Jones – tread now, Cooper<br />

trod, slightly unsteadily at first. With a few<br />

tweaks here and there (references to “blacks”,<br />

slight wobbliness when it comes to gays),<br />

you could run any of her Seventies columns<br />

today and they wouldn’t have dated at all.<br />

But Cooper claims she never intended to be<br />

a writer. “Well, I just thought I’d get married<br />

and have children,” she says, settling into<br />

an armchair. It’s earlier in the day – we<br />

haven’t opened the champagne yet.<br />

We’re in a drawing room – shabby,<br />

warm, plant-filled, with almost every nook<br />

and cranny taken up with animalalia: china<br />

dogs, a stuffed badger, cushions with pictures<br />

of late pets. Cooper is a renowned defender<br />

of animal rights. She was one of the major<br />

fundraisers for the gigantic Animals in<br />

War memorial on Park Lane, London.<br />

“I didn’t have any idea of a career,” she<br />

continues. Cooper applied for Oxford having<br />

flunked her A levels, and instead sat its<br />

entrance exam. She failed that too in a blaze<br />

of typical behaviour. “I hit Oxford and went<br />

berserk,” she beams. “I went to parties every<br />

single night. It was the first time I’d ever had<br />

a drink. One of the graduates had to carry<br />

me home, like a coffin – it was so funny.”<br />

Hungover at the interview, Cooper was<br />

turned down flat. Her parents – an Army<br />

brigadier and his “nervous” wife – were<br />

heartbroken. “But I’m rather glad I didn’t go,”<br />

Cooper says with her trademark cheerfulness.<br />

“I’m glad I’m not academic. I would probably<br />

have gone on to write boring biographies.”<br />

That, of course, is exactly what didn’t<br />

happen. For in 1985 Cooper progressed<br />

from Fleet Street columns (bagged when<br />

she amused the Sunday Times editor at<br />

The Times Magazine 39<br />

11 September 2010<br />

PAGE 39<br />

ttm11039 3 06/09/2010 15:25

PETER ROSENBAUM/SCOPE FEATURES<br />

a dinner party) to her first big novel, Riders.<br />

It was so risqué that her bank manager asked<br />

Leo, in horror, “How does <strong>Jilly</strong> know about<br />

such things?” “Showjumpers are not like<br />

this,” Horse & Hound thundered.<br />

“I read it now and my hair stands on end,”<br />

Cooper says, looking scandalised by herself<br />

– but also, to be fair, looking like she’s greatly<br />

enjoying being scandalised by herself as well.<br />

“Blowjobs! There’s blowjobs everywhere.<br />

I remember my editor saying: ‘Darling, do<br />

you think you should have this bit about<br />

sperm trickling down the thigh?’ I mean,<br />

it’s not nice. But we were in this little pocket<br />

– from the Sixties to the mid-Eighties – where<br />

people weren’t worried about sex. We had<br />

contraception, it was before Aids; it was joyful<br />

and exploratory. We were a young couple –<br />

the Coopers. We had a lot of people asking us<br />

to go to bed with them. Although we didn’t!”<br />

This can-do-you attitude feeds into the<br />

books, which – much like those of her rival of<br />

the time, Jackie Collins – are full of enjoyably<br />

diva-ish characters landing on the lawns of<br />

their mansions in helicopters, ordering crates<br />

of Dom Pérignon, then rutting all night long.<br />

Unlike Collins’, however, Cooper’s books<br />

are unmistakably British, and all the better<br />

for it: people crack puns mid-coitus, there<br />

are breathless descriptions of herbaceous<br />

borders and darling spaniels, and there’s an<br />

air of uplifting jolliness to the whole thing,<br />

which makes sex seem like a total hoot.<br />

Pre-internet, this was how most women<br />

of my generation learnt about sex. Get any<br />

group of thirtyso<strong>met</strong>hing women together<br />

now, and the chances are that, after a couple<br />

of cocktails, they can still quote the filthy bits<br />

from Riders, Rivals, Polo, The Man Who Made<br />

Husbands Jealous and Pandora word for word.<br />

Cooper’s Rutshire was the world we escaped<br />

to as teenagers. It was Sex Narnia. <strong>When</strong> I<br />

needed a nom de plume for writing, I named<br />

myself after one of the characters in Rivals, for<br />

goodness’ sake. Without Cooper, I would still<br />

be plain old Catherine Moran.<br />

It’s fitting, then, to discover why Cooper<br />

has such an affinity with the escapist desires<br />

of teenage girls: as a teenage girl, she had<br />

some escaping to do herself. Becoming<br />

distressed at the mention of it – her hands<br />

start to fly around, like birds – she mentions<br />

how terribly “anxious” her mother would<br />

get every time they had to move house to<br />

follow Cooper’s father from Army posting to<br />

posting. So<strong>met</strong>imes, her mother would have<br />

to “go away” for a while – to hospital – to<br />

recover. <strong>When</strong> Cooper went away herself,<br />

to an all-girls boarding school, she left<br />

early, having told her parents she was<br />

“dying of emotional anaemia”.<br />

I suspect it was around this time that<br />

Cooper began to develop her characteristic<br />

life-long cheerfulness, the kind of merriness<br />

<strong>Jilly</strong> and Leo still light<br />

up around each other.<br />

There’s a teenage air to<br />

their teasy conversations<br />

that has its roots in a steely determination not<br />

to give in to melancholy or despair, because<br />

the consequences of that are known all too<br />

well. I wonder if it’s also Cooper’s upbringing<br />

that triggered her other notable trait: an oftproclaimed<br />

unwillingness to be a writer.<br />

In a corner of the drawing room, on<br />

a chair, sits a rackety old manual typewriter<br />

called Monica. Cooper wrote every single<br />

one of her books on Monica, including her<br />

latest, Jump!. I ask her if she feels happiest<br />

behind her typewriter, in control of her<br />

world, as you would expect from someone<br />

who’s been writing for 41 years.<br />

“Goodness, no!” Cooper says, horrified.<br />

“I’m awful when I’m writing a book. My<br />

editors and agents are always so lovely, but<br />

I take for ever, and there’s always a point<br />

where I think I can’t finish it, and I stretch<br />

the deadline and stretch the deadline, and<br />

they worry they won’t ever see it at all,<br />

and I struggle terribly. Terribly.”<br />

She says she was forced to start writing<br />

Rivals “because we’d lost all our money.<br />

I was terribly worried about money”, and that<br />

she still writes now out of financial necessity:<br />

the upkeep of the house and, increasingly, the<br />

cost of care for Leo, who has Parkinson’s.<br />

I <strong>met</strong> Leo earlier. He has a nookish,<br />

book-lined office, cheerfully insists, “You must<br />

smoke if you want to smoke. I believe in that,”<br />

and has a wheelchair he lets me sit in while<br />

I drink my tea. He and Cooper are clearly<br />

very fond of each other – they still light up<br />

With Leo, her husband<br />

of 49 years, who now<br />

suffers from Parkinson’s<br />

The NOVELIST<br />

around each other, after 49 years of<br />

marriage, and there’s an almost teenage air<br />

to their teasy, nudging conversations. Cooper<br />

recently had a health setback herself: a<br />

stroke, although minor. As she perches on<br />

Leo’s desk, a small but still livid scar from<br />

a subsequent operation is apparent; the<br />

only visible consequence, it seems. One’s<br />

first instinct might be to pity this 73-yearold<br />

woman with a scar on her neck, still<br />

forced to write gigantic blockbuster novels<br />

in order to keep the family afloat.<br />

But as we repair to the kitchen, get stuck<br />

into the champagne and start a gossip session<br />

that is never less than 100 per cent libellous<br />

(“So has [big name Fleet Street columnist]<br />

gone completely mad? And you know, of<br />

course, that [huge political figure] was having<br />

an affair with [another huge political figure]?”),<br />

and Cooper talks about writing, and the<br />

media, with the passion of a master of<br />

her craft – someone with the whole awful,<br />

drunken, amazing, ridiculous industry in their<br />

blood – a suspicion starts to form in my mind.<br />

Finally – as we open the third bottle<br />

of wine, over the laughably untouched<br />

quiche and salad – I trot it out.<br />

“I think that, secretly, you’re glad your<br />

financial situation means you have to keep<br />

writing,” I say, unsteadily pushing my glass<br />

towards Cooper’s equally unsteady bottle.<br />

“Because if you didn’t have to write, you would<br />

never have had the excuse to go and lock<br />

yourself in your room with your typewriter<br />

in 1969, and just sit down and write. I think<br />

women writers almost always need an excuse<br />

to indulge in the selfishness of creativity.<br />

I think when you started, the only way<br />

you could ever have said, ‘Go away –<br />

Mummy has to write now,’ is if it were<br />

from dire financial need. And you still feel<br />

that you need that excuse now, even though<br />

you’re 73 and have sold 15 million books.”<br />

Cooper stares at me for a moment,<br />

wine-ishly. “You’re quite right,” she says,<br />

finally. “Brilliant. Brilliant. You’re quite right.<br />

It’s absolutely true about that, isn’t it? It is<br />

self-gratification, isn’t it? You’re so right.<br />

So right. More wine?”<br />

<strong>When</strong> I finally pour myself onto a train,<br />

an hour later, I spend the first half of the<br />

journey gloating that I’ve cracked the essential<br />

conundrum at the heart of one of my all-time<br />

heroes. God, I’m great. I’ve totally nailed it.<br />

Look at me, with my insights.<br />

Around Reading, however, it occurs to<br />

me that <strong>Jilly</strong> Cooper is so lovely, and was so<br />

tipsy, she would probably have said anything<br />

at that point to get me out of her kitchen. ■<br />

Jump! by <strong>Jilly</strong> Cooper is published by Bantam<br />

<strong>Press</strong> on Thursday and is available from The<br />

Times Bookshop priced £16.99 (RRP £18.99),<br />

free p&p: 0845 2712134; thetimes.co.uk/bookshop<br />

The Times Magazine 41<br />

11 September 2010<br />

PAGE 41<br />

ttm11041 4 06/09/2010 12:22