Chapter 6: The Declaration of Independence Guiding Question ...

Chapter 6: The Declaration of Independence Guiding Question ...

Chapter 6: The Declaration of Independence Guiding Question ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

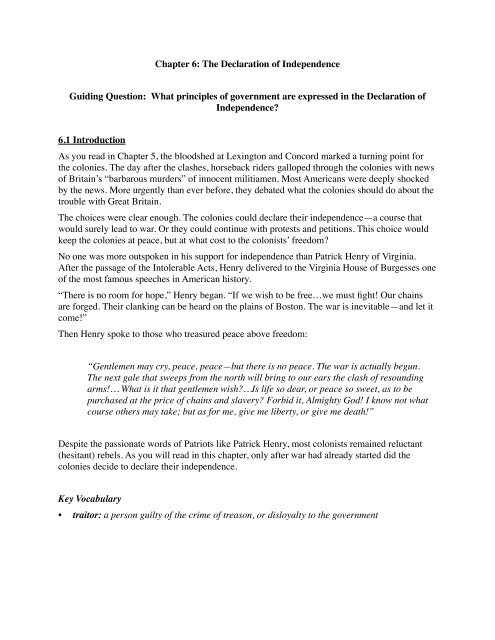

<strong>Chapter</strong> 6: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Declaration</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Independence</strong><br />

<strong>Guiding</strong> <strong>Question</strong>: What principles <strong>of</strong> government are expressed in the <strong>Declaration</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Independence</strong>?<br />

6.1 Introduction<br />

As you read in <strong>Chapter</strong> 5, the bloodshed at Lexington and Concord marked a turning point for<br />

the colonies. <strong>The</strong> day after the clashes, horseback riders galloped through the colonies with news<br />

<strong>of</strong> Britain’s “barbarous murders” <strong>of</strong> innocent militiamen. Most Americans were deeply shocked<br />

by the news. More urgently than ever before, they debated what the colonies should do about the<br />

trouble with Great Britain.<br />

<strong>The</strong> choices were clear enough. <strong>The</strong> colonies could declare their independence—a course that<br />

would surely lead to war. Or they could continue with protests and petitions. This choice would<br />

keep the colonies at peace, but at what cost to the colonists’ freedom?<br />

No one was more outspoken in his support for independence than Patrick Henry <strong>of</strong> Virginia.<br />

After the passage <strong>of</strong> the Intolerable Acts, Henry delivered to the Virginia House <strong>of</strong> Burgesses one<br />

<strong>of</strong> the most famous speeches in American history.<br />

“<strong>The</strong>re is no room for hope,” Henry began. “If we wish to be free…we must fight! Our chains<br />

are forged. <strong>The</strong>ir clanking can be heard on the plains <strong>of</strong> Boston. <strong>The</strong> war is inevitable—and let it<br />

come!”<br />

<strong>The</strong>n Henry spoke to those who treasured peace above freedom:<br />

“Gentlemen may cry, peace, peace—but there is no peace. <strong>The</strong> war is actually begun.<br />

<strong>The</strong> next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash <strong>of</strong> resounding<br />

arms!… What is it that gentlemen wish?…Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be<br />

purchased at the price <strong>of</strong> chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what<br />

course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death!”<br />

Despite the passionate words <strong>of</strong> Patriots like Patrick Henry, most colonists remained reluctant<br />

(hesitant) rebels. As you will read in this chapter, only after war had already started did the<br />

colonies decide to declare their independence.<br />

Key Vocabulary<br />

• traitor: a person guilty <strong>of</strong> the crime <strong>of</strong> treason, or disloyalty to the government

6.2 <strong>The</strong> War Begins<br />

On May 10, 1775, the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia. By then, New England<br />

militia had massed around Boston. <strong>The</strong> first question facing Congress was who should command<br />

this “New England Army.” <strong>The</strong> obvious answer was a New Englander.<br />

George Washington and the Continental Army John Adams <strong>of</strong> Massachusetts had another idea.<br />

He proposed that Congress create a “continental army” made up <strong>of</strong> troops from all the colonies.<br />

To lead this army, Adams nominated “a gentleman whose skill as an <strong>of</strong>ficer, whose…great talents<br />

and universal character would…unite…the colonies better than any other person alive.” That<br />

man was George Washington <strong>of</strong> Virginia.<br />

<strong>The</strong> delegates agreed. <strong>The</strong>y unanimously elected Washington to be commander-in-chief <strong>of</strong> the<br />

new Continental Army.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Battle <strong>of</strong> Bunker Hill<br />

Meanwhile, militiamen near Boston made plans to fortify two hills that overlooked the city—<br />

Bunker Hill and Breed’s Hill. On the night <strong>of</strong> June 16, Israel Putnam led a few hundred men up<br />

Breed’s Hill. In four hours <strong>of</strong> furious digging, they erected a crude fort on the top <strong>of</strong> the hill.<br />

<strong>The</strong> fort worried British general William Howe, who had just arrived from England with fresh<br />

troops. Howe ordered an immediate attack. Under a hot June sun, some 2,000 redcoated troops<br />

formed two long lines at the base <strong>of</strong> Breed’s Hill. At Howe’s order, they marched up the slope.<br />

As the lines moved ever closer, Putnam ordered his men, “Don’t fire until you see the whites <strong>of</strong><br />

their eyes.” Only when the British were almost on top <strong>of</strong> them did the militiamen pull their<br />

triggers. <strong>The</strong> red lines broke and fell back in confusion.<br />

<strong>The</strong> British regrouped and attacked again. Once more the Americans stopped their advance. On<br />

their third attack, the redcoats finally took the hill—but only because the Americans had used up<br />

all their gunpowder and pulled back.<br />

This clash, which was misnamed the Battle <strong>of</strong> Bunker Hill, was short but very bloody. More than<br />

1,000 British troops were killed or wounded, and nearly half that many Americans. British and<br />

Americans alike knew that this was no small skirmish on a village green. A war had begun.

6.3 <strong>The</strong> Siege <strong>of</strong> Boston<br />

A week later, George Washington took command <strong>of</strong> his new army. He found “a mixed multitude<br />

<strong>of</strong> people…under very little discipline, order, or government.” Washington worked hard to<br />

impose order. One man wrote, “Everyone is made to know his place and keep in it… . It is<br />

surprising how much work has been done.”<br />

Ticonderoga<br />

A month later, a dismayed Washington learned that the army had only 36 barrels <strong>of</strong> gunpowder—<br />

enough for each soldier to fire just nine shots. To deceive the British, Washington started a rumor<br />

in Boston that he had 1,800 barrels <strong>of</strong> gunpowder—more than he knew what to do with! Luckily,<br />

the British swallowed this tall tale. Meanwhile, Washington sent desperate letters to the colonies<br />

begging for gunpowder.<br />

Washington got his powder. But he still did not dare attack the British forces in Boston. To do<br />

that he needed artillery—heavy guns, such as cannons—to bombard their defenses. In<br />

desperation, Washington sent a Boston bookseller named Henry Knox to Fort Ticonderoga to<br />

round up some big guns.<br />

Ticonderoga was an old British fort located at the southern end <strong>of</strong> Lake Champlain in New York.<br />

A few months earlier, militiamen led by Ethan Allen and Benjamin Arnold had seized the fort.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Americans had little use for the run-down fort, but its guns would prove priceless.<br />

As winter set in, Knox loaded 59 cannons onto huge sleds and dragged them 300 miles to<br />

Boston. Knox’s 42 sleds also carried 2,300 pounds <strong>of</strong> lead for future bullets. Boston was about to<br />

be put under siege.<br />

<strong>The</strong> British Abandon Boston<br />

On March 4, 1776, the British soldiers in Boston awoke to a frightening sight. <strong>The</strong> night before,<br />

the ridges <strong>of</strong> nearby Dorchester Heights had been bare. Now they bristled with cannons, all<br />

aimed on the city.<br />

Rather than risk another bloodbath, General Howe abandoned the city. Within days, more than a<br />

hundred ships left Boston Harbor for Canada. <strong>The</strong> ships carried 9,000 British troops as well as<br />

1,100 Loyalists who preferred to leave their homes behind rather than live with rebels.<br />

Some Americans hoped the war was over. Washington, however, knew that it was only<br />

beginning.

6.4 Toward <strong>Independence</strong><br />

Nearly a year passed between the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord and the British retreat<br />

from Boston. During that time, there was little talk <strong>of</strong> independence. Most colonists still<br />

considered themselves loyal British subjects. <strong>The</strong>ir quarrel was not with Great Britain itself, but<br />

with its policies toward the colonies.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Olive Branch Petition<br />

Many Americans pinned their hopes for peace on King George. In July 1775, Congress sent a<br />

petition to George III asking him to end the quarrel. John Adams called the petition an “olive<br />

branch,” because olive tree branches are an ancient symbol <strong>of</strong> peace.<br />

By the time the petition reached London, however, the king had declared the colonies to be in<br />

“open and avowed rebellion.” He ordered his ministers “to bring the traitors to justice.”<br />

Being called a traitor was enough to change the mind <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> Washington’s generals. <strong>The</strong><br />

general confessed that he had long “looked with some degree <strong>of</strong> horror on the scheme <strong>of</strong><br />

separation.” Now he agreed with Patrick Henry that “we must be independent or slaves.”<br />

Common Sense<br />

Many colonists, however, still looked with “horror” at the idea <strong>of</strong> independence. <strong>The</strong>n, early in<br />

1776, a Patriot named Thomas Paine published a fiery pamphlet entitled Common Sense. Paine<br />

sc<strong>of</strong>fed at the idea that Americans owed any loyalty to King George.<br />

“Of more worth is one honest man to society,” he wrote, “than all the crowned ruffians who ever<br />

lived.”<br />

Paine also attacked the argument that the colonies’ ties to Britain had benefited Americans. Just<br />

the opposite was true, he said. American trade had suffered under British control. Americans had<br />

also been hurt by being dragged into Britain’s European wars.<br />

Paine ended with a vision <strong>of</strong> an independent America as a homeland <strong>of</strong> liberty. “Ye that love<br />

mankind!” he urged. “Ye that dare oppose not only the tyranny, but the tyrant, stand forth!… <strong>The</strong><br />

sun never shined on a cause <strong>of</strong> greater worth.”<br />

Within a few months, more than 120,000 copies <strong>of</strong> Common Sense were printed. Paine’s<br />

arguments helped persuade thousands <strong>of</strong> colonists that independence was not only sensible, but<br />

the key to a brighter future.<br />

Fast Fact<br />

• Thomas Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense persuaded many colonists to support<br />

independence.

6.5 Thomas Jefferson Drafts a <strong>Declaration</strong><br />

A few weeks after the British left Boston, the Continental Congress appointed a committee to<br />

write a declaration, or formal statement, <strong>of</strong> independence. <strong>The</strong> task <strong>of</strong> drafting the declaration<br />

went to the committee’s youngest member, 33-year-old Thomas Jefferson <strong>of</strong> Virginia. A shy man,<br />

Jefferson said little in Congress. But he spoke brilliantly with his pen.<br />

Jefferson’s job was to explain to the world why the colonies were choosing to separate from<br />

Britain. “When in the course <strong>of</strong> human events,” he began, if one people finds it necessary to<br />

break its ties with another, “a decent respect to the opinions <strong>of</strong> mankind” requires that they<br />

explain their actions.<br />

Natural Rights<br />

Jefferson’s explanation was simple, but revolutionary. Loyalists had argued that colonists had a<br />

duty to obey the king, whose authority came from God. Jefferson reasoned quite differently. All<br />

people are born equal in God’s sight, he began, and all are entitled to the same basic rights. In<br />

Jefferson’s eloquent words:<br />

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are<br />

endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life,<br />

liberty, and the pursuit <strong>of</strong> happiness.”<br />

Governments are formed, Jefferson said, “to secure these rights.” <strong>The</strong>ir power to rule comes<br />

from “the consent <strong>of</strong> the governed.” If a government fails to protect people’s rights, “it is the<br />

right <strong>of</strong> the people to alter or abolish it.” <strong>The</strong> people can then create a new government that will<br />

protect “their safety and happiness.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> King’s Crimes<br />

King George, Jefferson continued, had shown no concern for the rights <strong>of</strong> colonists. Instead, the<br />

king’s policies had been aimed at establishing “an absolute tyranny over these states [the<br />

colonies].”<br />

As pro<strong>of</strong>, Jefferson included a long list <strong>of</strong> the king’s abuses. In all these actions, Jefferson<br />

claimed, George III had shown that he was “unfit to be the ruler <strong>of</strong> a free people.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> time had come, Jefferson concluded, for the colonies’ ties to Britain to be broken. “<strong>The</strong>se<br />

United Colonies are,” he declared, “and <strong>of</strong> right ought to be, free and independent states.”<br />

Fast Fact<br />

• After Thomas Jefferson wrote the first draft <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Declaration</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Independence</strong>, Benjamin<br />

Franklin and John Adams suggested changes.

6.6 <strong>The</strong> Final Break<br />

On July 1, 1776, the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia’s State House to debate<br />

independence. By noon, the temperature outside had soared into the nineties, and a thunderstorm<br />

was gathering. Inside the State House, emotions were equally hot and stormy. By the end <strong>of</strong> the<br />

day, the issue was still undecided.<br />

<strong>The</strong> next day was cooler and calmer. On July 2, 12 colonies voted for independence. New York<br />

cast no vote.<br />

No delegate was more excited about the colonies’ decision than John Adams. He wrote to his<br />

wife Abigail, “<strong>The</strong> second <strong>of</strong> July…will be celebrated by succeeding generations…with pomp<br />

and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires and illuminations, from one end <strong>of</strong><br />

the continent to the other, from this time forward forevermore.”<br />

Debate over Slavery<br />

Adams was wrong about the date that would be celebrated as America’s birthday, but only<br />

because Congress decided to revise Jefferson’s declaration. Most <strong>of</strong> the delegates liked what they<br />

read, except for a passage on slavery. Jefferson had charged King George with violating the<br />

“sacred rights <strong>of</strong> life and liberty…<strong>of</strong> a distant people [by] carrying them into slavery.”<br />

Almost no one liked this passage. Southerners feared that it might lead to demands to free the<br />

slaves. Northerners worried that New England merchants, who pr<strong>of</strong>ited from the slave trade,<br />

might be <strong>of</strong>fended. Even delegates who opposed slavery felt that it was unfair to blame the king<br />

for enslaving Africans. <strong>The</strong> passage was struck out.<br />

<strong>Independence</strong> Day<br />

On July 4, the delegates approved a final version <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Declaration</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Independence</strong>. One by<br />

one, they stepped forward to sign it. In doing so, they pledged to support independence with “our<br />

lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.”<br />

This was a serious pledge. Every signer knew that he was committing an act <strong>of</strong> treason against<br />

Great Britain. If the new “United States <strong>of</strong> America” failed to win its freedom, each <strong>of</strong> them<br />

could end up swinging from a hangman’s rope. Knowing this, Benjamin Franklin told the<br />

delegates, “We must all hang together. Or most assuredly we shall all hang separately.”<br />

Fast Fact<br />

• Slavery was not mentioned in the <strong>Declaration</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Independence</strong> because the slave trade was<br />

important to the economy <strong>of</strong> many <strong>of</strong> the colonies. In a triangular trade, rum and iron were<br />

shipped from New England to West Africa. In West Africa, these products were exchanged for<br />

slaves. <strong>The</strong>n the slaves were taken to the West Indies (Caribbean), where they were traded for<br />

molasses and sugar. Finally, the molasses and sugar were brought back to New England.

6.7 <strong>Chapter</strong> Summary<br />

In this chapter, you read how the American colonies took the dramatic step <strong>of</strong> declaring their<br />

independence. You used a visual metaphor to describe the key historic events that led up to the<br />

<strong>Declaration</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Independence</strong>. Soon after the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord, the struggle<br />

with Great Britain turned into all-out war. <strong>The</strong> Second Continental Congress elected George<br />

Washington as the head <strong>of</strong> the Continental Army. After the bloody Battle <strong>of</strong> Bunker Hill,<br />

American troops threatened the city <strong>of</strong> Boston with heavy guns. <strong>The</strong> British decided to abandon<br />

the city.<br />

<strong>The</strong> failure <strong>of</strong> the Olive Branch Petition, and Thomas Paine’s eloquent pamphlet, Common<br />

Sense, moved the colonies closer to a declaration <strong>of</strong> independence. Thomas Jefferson, a delegate<br />

to the Second Continental Congress, was selected to write a draft <strong>of</strong> the declaration.<br />

On July 4, 1776, the delegates took their lives in their hands by signing the <strong>Declaration</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Independence</strong>. For the first time in history, a government was being established on the basis <strong>of</strong><br />

the natural rights <strong>of</strong> people and the duty <strong>of</strong> government to honor those rights.<br />

But independence could not be won with words alone. As you will read in the next chapter, the<br />

colonies now faced the challenge <strong>of</strong> winning a war against the most powerful nation in the<br />

world.<br />

Fifty-six men signed the <strong>Declaration</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Independence</strong>. Who were they, and what happened to<br />

them?<br />

As a group, the signers were wealthy and well educated. Twenty-four were lawyers or judges.<br />

Eleven were merchants. Nine were farmers or plantation owners.<br />

<strong>The</strong> signers pledged their lives to defend the <strong>Declaration</strong>. Many paid dearly for that promise.<br />

Carter Braxton, a wealthy planter and trader from Virginia, lost his ships to the British navy<br />

during the war. After selling his home and property to pay his debts, he died in rags.<br />

Late in the war, Thomas Nelson, Jr. saw his home taken over by the British as a headquarters<br />

before a major battle. He told General Washington to open fire on the house. Nelson’s home was<br />

destroyed, and he died a poor man.<br />

Francis Lewis and John Hart lost more than their homes and property. <strong>The</strong> British put Lewis’s<br />

wife in jail, and she died shortly after. Hart lived in forests and caves for more than a year after<br />

fleeing the British. When he returned, his wife was dead and his 13 children were nowhere to be<br />

found. Saddened and exhausted, he died a few weeks later.<br />

Twelve <strong>of</strong> the signers had their homes burned. Five were captured by the British and tortured<br />

before they died. Nine died from wounds or hardships suffered during the war. <strong>The</strong> sons <strong>of</strong> two<br />

signers were killed while serving in the army.<br />

Thousands <strong>of</strong> other women and men, both famous and forgotten, suffered terrible losses during<br />

the war with Britain. Like the signers <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Declaration</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Independence</strong>, they pledged all they<br />

cared about to the cause that united them.