View PDF - Caleb Daniloff

View PDF - Caleb Daniloff

View PDF - Caleb Daniloff

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

TheArtof War<br />

For centuries, strict rules of warfare<br />

dictated how armies engaged on the<br />

battlefield.<br />

As proxy militias, suicide bombers,<br />

and private contractors proliferate,<br />

the rules are being rewritten—and<br />

Kateri Carmola is attempting to<br />

make sense of it all.<br />

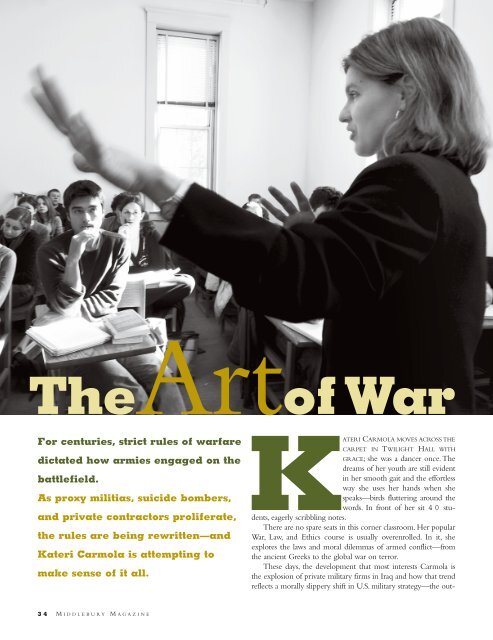

KATERI CARMOLA MOVES ACROSS THE<br />

CARPET IN TWILIGHT HALL WITH<br />

GRACE; she was a dancer once. The<br />

dreams of her youth are still evident<br />

in her smooth gait and the effortless<br />

way she uses her hands when she<br />

speaks—birds fluttering around the<br />

words. In front of her sit 40 students,<br />

eagerly scribbling notes.<br />

There are no spare seats in this corner classroom. Her popular<br />

War, Law, and Ethics course is usually overenrolled. In it, she<br />

explores the laws and moral dilemmas of armed conflict—from<br />

the ancient Greeks to the global war on terror.<br />

These days, the development that most interests Carmola is<br />

the explosion of private military firms in Iraq and how that trend<br />

reflects a morally slippery shift in U.S. military strategy—the out-<br />

34<br />

M IDDLEBURY<br />

M A GAZINE

B Y C A L E B D A N I L O F F<br />

P H O T O G R A P H S B Y B R I D G E T B E S A W G O R M A N<br />

sourcing of missions, from combat to interrogation. In short, U.S.<br />

foreign policy is being executed, in no small part, by a largely<br />

unregulated private sector.<br />

Carmola steps away from the chalkboard, her fingertips<br />

smudged white. Today’s topic: the breakdown and restoration of<br />

restraint in warfare.The sleeves on her black button-down blouse<br />

are rolled to the elbow.White lines from road salt squiggle along<br />

the toes of her leather boots.<br />

An assistant professor of political science and a Christian A.<br />

Johnson Fellow in Political Philosophy, Carmola has written articles<br />

and helped organize national conferences about the topic of<br />

outsourcing national security—including one on campus last<br />

fall—and belongs to an electronic forum for security contractors<br />

in Iraq. She’ll take next year off from the classroom to finish a<br />

book on the subject.<br />

“I want people to realize the cost of our foreign policies,” she<br />

says later.“We tend to imagine these policies are costless, when, in<br />

fact,they are just being borne by people who are out of our sight.”<br />

Carmola is the faculty’s lone Vermont native, hailing from<br />

St. Albans, an industrial town in the state’s northwest corner. She<br />

exudes a no-nonsense, down-to-earth sensibility. In class, she<br />

explains why it is important for students to own certain books<br />

(Crimes of War:What the Public Should Know, Eichmann in Jerusalem:<br />

A Report on the Banality of Evil), quipping that the price of one is<br />

S PRING 2005<br />

35

equal to “just five Starbucks lattes.”Her students consider Carmola<br />

firm, yet approachable, as curious about them as they are about<br />

her.<br />

Emily Berlanstein ’05, an English major from Baltimore,<br />

Maryland, says: “This may sound unsophisticated, but Professor<br />

Carmola is awesome. She’s someone who ignores textbooks<br />

because it’s much more fun to discover the theories via first-hand<br />

accounts. She’s energetic and has a real knack for connecting with<br />

young people, without failing to remind them who’s boss. (I’ve<br />

seen her throw chalk at a boy sleeping in the front row).”<br />

Carmola’s lessons are also playing out on the battlefields of<br />

Iraq. U.S. Marine Captain Michael<br />

Hunzeker, 27, was a student of<br />

Carmola’s when she taught at the<br />

University of California, Berkeley,<br />

before coming to Middlebury. He<br />

took part in the ground invasion in<br />

March 2003 and has trained hundreds<br />

of Marines for battle.<br />

“It’s easy to talk about a humane<br />

war,” Captain Hunzeker says.<br />

“Explaining it to a group of 18-yearold<br />

Marines on the eve of an offensive<br />

is a bit more difficult. Ms. Carmola<br />

helped me deal with the toughest<br />

question, one I heard over and over as<br />

I attempted to explain the rules of engagement to every Marine—<br />

‘Sir, why should we play by the rules when we know the enemy<br />

won’t?’ She helped me understand the larger picture surrounding<br />

the rules of war and gave me the tools to explain it in everyday<br />

terms so that the people who make the difference—our young<br />

warriors—could put it into action.”<br />

Because this course is so grounded in the real world, fascinating<br />

material arises daily.Aside from frequent bulletins on the war<br />

on terror, there are regular developments in a rapidly morphing<br />

U.S. military. In mid-February, the New York Times published several<br />

articles—one on the immense popularity among civilians of<br />

a military-devised video war game, another on the Pentagon’s<br />

push to develop robots for possible combat operations.The latter<br />

speaks to Carmola’s concern with moral equality on the battlefield.<br />

“Quick thought: would you want to play sports with robots?”<br />

she asks. Carmola posts these articles on the course Web site, and<br />

recently added an instant-message exchange between one of her<br />

students and a soldier friend now serving in Afghanistan. It touches<br />

upon many of her research themes: the glorification of soldiers,<br />

the dynamics of protesting war, military careerism, and excessive<br />

contracting. (“The stories I have—,” the soldier writes, “You’ll<br />

never want to pay taxes again.”) In short, the great appeal of<br />

Carmola’s course is that it unfolds in real time.<br />

IN HIGH SCHOOL, it was dance, not war that fired Carmola’s<br />

mind.After graduating in the early 1980s, she left Vermont<br />

to attend NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. She was an eager<br />

teenager with a head full of city dreams. But life has a knack for<br />

sticking its foot out.<br />

“It’s a clash of ethos—<br />

of the business culture<br />

and military culture.<br />

You never hear words<br />

like ‘virtue’ and<br />

‘honor’ in the business<br />

world.”<br />

Tisch freshmen were required to take a yearlong writing<br />

course; Carmola’s was taught by a grad student and aspiring playwright.“He<br />

came in and said,‘You’re all dancers, or you’re actors,<br />

or Tisch School of the Arts students, so by my definition, you’re all<br />

dumb,’” she recalls.“‘You’ve allowed your body to be the tool of<br />

someone else’s mind, and I want you to reacquire your mind.’”<br />

The instructor’s name was Tony Kushner, destined to become<br />

one of America’s most influential playwrights. And his words<br />

helped set the tone for Carmola’s intellectual life.“By the end of<br />

that year with him, I was so taken with thinking about the world,”<br />

she says.<br />

Carmola gave up dance and transferred<br />

to Columbia to pursue a degree<br />

in Russian, but she says she wanted<br />

even greater academic intensity and<br />

left the following year for the<br />

University of Chicago, an institution<br />

known for devoting entire courses to a<br />

single text. (“I felt I had years of education<br />

to make up for,” she says.)<br />

On campus,the intellectual energy<br />

was palpable. Students protested not<br />

investment in South Africa but the<br />

slashing of library hours. One of<br />

Carmola’s professors, a Holocaust survivor,<br />

had taught himself Greek and<br />

read Thucydides by candlelight in hidden crawl spaces. Carmola<br />

felt she’d found a home.<br />

In the summers, she returned to Vermont and worked “totally<br />

non-intellectual jobs. It was the perfect balance,” she smiles.“I<br />

needed to get away from the city and from books. On the farm,<br />

we used to say you’d go beyond boredom.And there was kind of<br />

a neat, trippy space beyond boredom.”<br />

After graduating magna cum laude with a degree in tutorial<br />

studies, she moved to New Mexico.Figuring law school was next,<br />

she worked at a large law firm. In the evenings, she tutored at the<br />

Santa Fe Indian School, supervising ninth-grade Pueblo and Hopi<br />

students serving detention. It was here that her interest in warfare<br />

began.To engage the boys, many of whom were the relatives of<br />

Vietnam vets or interested in World War II Navajo code breakers,<br />

she brought in books on war. The connection was immediate,<br />

deep, and she still keeps in touch with some of those students.<br />

Carmola grew tired of law work and taught at a private school<br />

for a year, but her mind was still restless. She applied to Berkeley<br />

to study the political role of women in Shakespeare but found<br />

herself distracted by thoughts of war—the Gulf War and later the<br />

paradoxical “humanitarian” wars—Somalia, Kosovo, Rwanda.<br />

She stayed at Berkeley for 10years, earning a Ph.D. and giving<br />

birth to two kids along the way. She went on to a postdoctoral<br />

position at the university,focusing on military ethics,and was considering<br />

a run for the local school board when an ad appeared for<br />

a political philosophy position at Middlebury.Three months later,<br />

she was on her way home. “When we landed it was manurespreading<br />

time,” she laughs. “You could smell it at the airport. It<br />

smelled like Vermont. I remember saying, ‘I feel like kissing the<br />

ground.’Which is overinflated, but I felt that way.”<br />

36<br />

M IDDLEBURY<br />

M A GAZINE

KATERI CARMOLA SITS AT A TABLE at Amigos Cantina, a<br />

Mexican eatery in downtown Middlebury. It’s a mild<br />

February evening, and the restaurant fills up quickly—<br />

groups of friends, local families with babies, an English professor<br />

and his son. Carmola plucks a tortilla chip from a basket and starts<br />

talking about some of the issues from her forthcoming book:<br />

Global Warriors: Private Contractors and the Ambiguities of National<br />

Strategy.<br />

There are 20,000 private contractors currently on the<br />

ground in Iraq, an unprecedented development, Carmola says.<br />

They carry out missions once handled by the military—guarding<br />

top U.S. officials, protecting oil pipelines, training Iraqi police, providing<br />

food for prisoners. Some 200 have been killed, but none<br />

make the official casualty count. It’s a $100-billion-a-year industry<br />

that makes up a quarter of the U.S. defense budget. Regulation<br />

is mild.The ethical implications have yet to catch up.“I think 10<br />

years down the line, this will all be more easily understood,” she<br />

says.“Now, it’s in this gray area.”<br />

Private companies can ease an overstretched military, freeing<br />

up more soldiers for battle, she says. But some critics see the contractors<br />

as modern mercenaries motivated by salaries that run as<br />

high as $15,000 a month.<br />

Blurring matters is the fact that Pentagon contracts are often<br />

awarded to U.S. firms that employ ex-military personnel from<br />

various countries—South America, South Africa, the former<br />

Soviet Union, Israel. Obviously, upholding the U.S. Constitution<br />

is not in everyone’s professional DNA. So identifying the buck, let<br />

alone figuring out where it stops, can become a puzzle.<br />

“Contracting makes a lot of economic sense but it also has this<br />

effect that the government can deny responsibility,” Carmola says,<br />

cutting into a chicken enchilada. “There are so many chains, so<br />

many links.”<br />

Two private military firms have been implicated in the Abu<br />

Ghraib torture scandal—CACI International Inc., of Arlington,<br />

Virginia, and Titan Corporation, of San Diego, California. Several<br />

of their civilian translators and interrogators are under investigation.<br />

Carmola has recently returned from a security conference at<br />

George Washington University, in Washington, D.C. Aside from<br />

regulation issues, panelists discussed tensions between the military<br />

and private sector, from bidding wars over translators to fundamental<br />

conflicts of interest. In many cases, both parties are serving<br />

the U.S. government. She recalls one exchange between a military<br />

official and a contractor.<br />

“‘You proceed at 90 miles an hour in armored vehicles<br />

through the streets of Baghdad,’ the officer said. ‘If you run over<br />

anybody or draw incoming fire or piss off a bunch of Iraqis, you<br />

don’t care because your mission is to keep your clients safe. Our<br />

mission is doing appropriate counterinsurgency which is trying to<br />

win the hearts and minds of these people.’”<br />

Carmola takes a sip from her drink.“It’s a clash of ethos—of<br />

the business culture and military culture, which are totally<br />

opposed,” she says.“You never hear words like ‘virtue’ and ‘honor’<br />

in the business world.”<br />

Carmola believes that this new mix reflects the Pentagon’s<br />

adjusted approach to warfare.While the September 11 terrorist<br />

attacks and the war on terror have obviously influenced strategy,<br />

the military had already been redefining itself. After Vietnam, the<br />

military, as well as the public, developed what Carmola calls “casualty<br />

phobia”—an aversion to soldier deaths and mutilations.<br />

Fighting from the air (as in Kosovo, where not a single plane was<br />

lost) became the norm. There was an increased use of Special<br />

Forces (“the darlings of the Defense Department,” she says). And<br />

the U.S. began to rely on indigenous outfits to help fight its battles,<br />

like the oft-abusive Northern Alliance in Afghanistan. In an<br />

article published last year in the International Journal of Politics and<br />

Ethics, Carmola raised the provocative question of whether this<br />

meant the U.S. was outsourcing war crimes, too.<br />

“One of my early thoughts was, Is our regular military so<br />

legally bound, so transparent, so professional that if you want all<br />

this dirty warfare going on, you have to sort of do it in a parallel<br />

universe, whether it’s special ops, CIA, or private contractors. Sort<br />

of like the Colombian military, which has paramilitaries do its<br />

dirty work. How much of that is really going on? It’s really hard<br />

to come out and say that.<br />

“There are a lot of decent, hard-working people in the security<br />

business, but recent allegations make me wonder what kind of<br />

restraints really work for this industry, particularly during this conflict.”<br />

Mark Evans, a professor of politics and international relations<br />

at the University of Wales Swansea, says Carmola is helping shape<br />

an important moral discussion on the shifting nature of war, especially<br />

as waged by the West. He anthologized one of her articles in<br />

his 2004 book Ethical Theory in the Study of International Politics.<br />

In the article, Carmola focuses on proxy forces, private security<br />

firms, and the proportional use of force.“Her ideas have helped to<br />

clarify—indeed, render very vivid—the issues at stake and have<br />

made significant contributions to this ongoing and highly relevant<br />

controversy,” Evans says.<br />

“Kateri’s current research explores a very hot topic,” says<br />

Allison Stanger, a professor of political science and the director of<br />

Middlebury’s Rohatyn Center for International Relations.“I very<br />

much look forward to reading the fruits of her upcoming research<br />

year.”<br />

And by the looks of it, Stanger won’t be alone. Publishers have<br />

already expressed interest. Carmola doesn’t seem too fazed by the<br />

attention. She compares herself to an anthropologist, simply trying<br />

to uncover what makes people and organizations tick. Rather<br />

than seeking to influence policy, she hopes her book will tell readers<br />

something about being a citizen in today’s complicated world.<br />

“I think it’s every academic’s dream to just find some kind<br />

of puzzle out there and try and loosen it up, make it more understandable,<br />

so that our decisions are more informed.”<br />

After dinner, she asks the waitress to wrap the rest of her chips<br />

and guacamole. A few minutes later, she steps outside and walks<br />

across Main Street toward her station wagon, keeping time with<br />

the forces shaping our world.<br />

<strong>Caleb</strong> <strong>Daniloff</strong> is a freelance writer in Middlebury. He’s a commentator<br />

for Vermont Public Radio and has written for the New York Times,<br />

Boston Globe, Boston Phoenix, and Publishers Weekly.<br />

S PRING 2005 37