Papermaking Where There is No Papermaking Tradition - (CUSAT ...

Papermaking Where There is No Papermaking Tradition - (CUSAT ...

Papermaking Where There is No Papermaking Tradition - (CUSAT ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Papermaking</strong> <strong>Where</strong> <strong>There</strong> <strong>is</strong><br />

<strong>No</strong> <strong>Papermaking</strong> <strong>Tradition</strong>:<br />

Two Months in South India<br />

dorothy field<br />

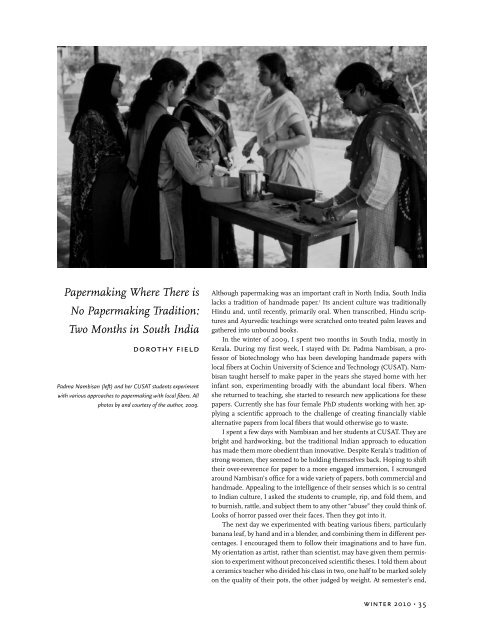

Padma Namb<strong>is</strong>an (left) and her <strong>CUSAT</strong> students experiment<br />

with various approaches to papermaking with local fibers. All<br />

photos by and courtesy of the author, 2009.<br />

Although ‐ papermaking was an important craft in <strong>No</strong>rth India, South India<br />

lacks a tradition of handmade paper. 1 Its ancient culture was traditionally<br />

Hindu and, until recently, primarily oral. When transcribed, Hindu scriptures<br />

and Ayurvedic teachings were scratched onto treated palm leaves and<br />

gathered into unbound books.<br />

In the winter of 2009, I spent two months in South India, mostly in<br />

Kerala. During my first week, I stayed with Dr. Padma Namb<strong>is</strong>an, a professor<br />

of biotechnology who has been developing handmade papers with<br />

local fibers at Cochin University of Science and Technology (<strong>CUSAT</strong>). Namb<strong>is</strong>an<br />

taught herself to make paper in the years she stayed home with her<br />

infant son, experimenting broadly with the abundant local fibers. When<br />

she returned to teaching, she started to research new applications for these<br />

papers. Currently she has four female PhD students working with her, applying<br />

a scientific approach to the challenge of creating financially viable<br />

alternative papers from local fibers that would otherw<strong>is</strong>e go to waste.<br />

I spent a few days with Namb<strong>is</strong>an and her students at <strong>CUSAT</strong>. They are<br />

bright and hardworking, but the traditional Indian approach to education<br />

has made them more obedient than innovative. Despite Kerala’s tradition of<br />

strong women, they seemed to be holding themselves back. Hoping to shift<br />

their over-reverence for paper to a more engaged immersion, I scrounged<br />

around Namb<strong>is</strong>an’s office for a wide variety of papers, both commercial and<br />

handmade. Appealing to the intelligence of their senses which <strong>is</strong> so central<br />

to Indian culture, I asked the students to crumple, rip, and fold them, and<br />

to burn<strong>is</strong>h, rattle, and subject them to any other “abuse” they could think of.<br />

Looks of horror passed over their faces. Then they got into it.<br />

The next day we experimented with beating various fibers, particularly<br />

banana leaf, by hand and in a blender, and combining them in different percentages.<br />

I encouraged them to follow their imaginations and to have fun.<br />

My orientation as art<strong>is</strong>t, rather than scient<strong>is</strong>t, may have given them perm<strong>is</strong>sion<br />

to experiment without preconceived scientific theses. I told them about<br />

a ceramics teacher who divided h<strong>is</strong> class in two, one half to be marked solely<br />

on the quality of their pots, the other judged by weight. At semester’s end,<br />

winter 2010 • 35

Pradeep, in charge of the papermaking workshop, trims a banana stalk in<br />

preparation for cooking it in lye.<br />

Pradeep and Bindhu form sheets on a large deckle box.<br />

the quality group had a few self-conscious pots; the quantity group<br />

had boxes of pots, some poorly made and awkward, others lively,<br />

imaginative, ingenious, even beautiful. 2 I hoped that by loosening<br />

them up and allowing them to make leaps and m<strong>is</strong>takes, they<br />

would design new and unusual papers.<br />

I continued south to Trivandrum, the capital of Kerala, and<br />

then to the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) Rural<br />

Centre, 16 kilometers outside the city. An Indian friend told me<br />

about the Rural Centre, a thoughtfully designed brick complex<br />

where poor women—battered, abandoned, widowed, or the sole<br />

support of their families—are hired to do the center’s work. My<br />

friend had shown me a few of their paper products: file folders,<br />

blank books, and soap wrappers, made from chemically dyed recycled<br />

paper and cotton waste. The paper was fairly substantial,<br />

adequate but generic, and similar to other papers being made in<br />

India today. In no way did it reflect the botanical richness of Kerala<br />

or the lives of the women who made it. I offered to volunteer with<br />

them to see whether we could make their paper more reflective of<br />

its origins.<br />

The Rural Centre <strong>is</strong> a small parad<strong>is</strong>e of mango, cashew, papaya,<br />

and coconut trees. Committed to environmental sustainability,<br />

SEWA <strong>is</strong> experimenting with small-scale farming, beekeeping,<br />

bio-diesel, and a new composting toilet. Several staff members<br />

support the Ayurvedic doctor whose office <strong>is</strong> there, preparing<br />

remedies, cooking, and housekeeping for h<strong>is</strong> patients, both Indian<br />

and foreign.<br />

Their papermaking began years ago when a Belgian woman<br />

taught a small group of women in a poor, remote area. They<br />

started with a few small screens and gradually expanded to their<br />

current setup. The center hired a man to make them a Hollander.<br />

He built a full-sized industrial beater with a greater capacity<br />

than required. It was difficult to adjust and wasted quantities of<br />

precious water. Their one large deckle box was very rusty. Since<br />

their instruction had been cursory, they routinely dripped water<br />

on newly formed sheets. Having no concept of the integrity of<br />

the deckle edge, they hung the paper to dry with the edges ripped<br />

and d<strong>is</strong>torted. That did not matter much since they trimmed their<br />

sheets. The power supply to the Hollander and the calendering<br />

press was reliably unreliable. Their market was largely notebooks<br />

and other items for conferences hosted at the Rural Centre. One<br />

or two young women and a young man, Pradeep, the only male<br />

employee, were assigned to the paper mill on a regular bas<strong>is</strong>. Four<br />

other women helped as needed. Pradeep was responsible for the<br />

Hollander, deckle box, screw press, guillotine, and calendering<br />

press as well as any other mechanical or technical tasks around<br />

the center.<br />

During my first few days there, we gathered banana leaves and<br />

stems, pineapple leaves, pandanus, and other local fibers; cooked<br />

them in lye; hand beat them; and formed them on small screens<br />

into thin sheets using okra as a formation aid and combining different<br />

fibers in varying percentages. These cr<strong>is</strong>p, undyed papers<br />

in natural colors, ranging from off-white through yellows, greens,<br />

and tans, were a radical departure from their usual output. We<br />

also combined local fibers with their regular recycled paper and<br />

cotton to make large sheets with more texture and v<strong>is</strong>ual interest.<br />

We added ferns and leaves, and experimented with blind embossing<br />

using large, deeply veined dry leaves. Though not startling by<br />

world standards, the results were very different from the handmade<br />

paper usually available in India.<br />

The Centre’s kitchen was equipped with propane burners, but<br />

to cook paper fibers we used traditional clay stoves under a tin roof.<br />

Fuel was the abundant supply of dry coconut leaves and ribs that<br />

fell from the Centre’s trees. Compared to their usual routine of<br />

loading the Hollander and flicking the switch, staff initially found<br />

36 • hand papermaking

Bindhu collects pineapple leaves for papermaking fiber.<br />

An ikat weaver at Pochampalli in Andra Pradesh, central India. <strong>No</strong>te the white<br />

marks around the terracotta pit where he sits at h<strong>is</strong> loom. These marks indicate<br />

cloth and thread’s sacred place in Indian culture, a status rarely granted paper.<br />

cooking and hand beating fiber laborious and time-consuming.<br />

<strong>Papermaking</strong> at the Rural Centre was a low priority compared<br />

to almost everything else. The women worked at SEWA because<br />

they needed a job, not out of interest in handmade paper and local<br />

fibers. They had not seen other handmade papers so they had<br />

nothing to compare theirs to. Despite the center’s commitment to<br />

sustainability, the women sloshed water wildly as they rinsed the<br />

cooked fiber. They were res<strong>is</strong>tant to even the most rudimentary<br />

system of measuring alkali, preferring to dump in lye in great random<br />

quantities. I carried pH strips in my pocket, testing the cook<br />

water and the rinsed fiber over and over. Gradually, they took an<br />

interest in a simple measuring system and obtaining pH papers.<br />

After we had made several batches of paper, I led them through<br />

the same exerc<strong>is</strong>e I had done with Namb<strong>is</strong>an’s PhD students—<br />

rumpling, crumpling, folding, tearing, and burn<strong>is</strong>hing a variety<br />

of papers. I introduced the idea of evaluating their paper in terms<br />

of how well it fulfilled the requirements of its intended use. Staff<br />

began asking questions and proposing experiments of their own.<br />

We talked about designing cards that reflected cultural traditions<br />

of Kerala. The women became conscious of not wasting fiber that<br />

had taken so long to prepare. I helped them to make journals with<br />

samples of the papers we had made and notes on our processes,<br />

a reference for them, though they did it mostly to humor me. We<br />

pers<strong>is</strong>ted. On the road up to the Rural Centre a military camp d<strong>is</strong>plays<br />

a large billboard: BASH ON REGARDLESS. I laughed the<br />

first time I saw it, then took it as my motto.<br />

I left the women on their own for a few days to take a short<br />

vacation north of Kerala. Before I left, I assigned some papermaking<br />

experiments. On my return, the staff proudly showed me their<br />

work. Unfortunately, during my final week, they received a large<br />

order for blank conference books made with their usual paper, so<br />

we could not pursue the new papers further. I left unsure whether<br />

they would continue the work we had begun. Six months later, I<br />

was thrilled to receive a stack of large sheets of the new papers that<br />

they had made after I left.<br />

Beyond refining South India’s handmade paper, the next challenge<br />

<strong>is</strong> market creation. In centuries past, India’s royal families<br />

were wealthy and d<strong>is</strong>criminating patrons of the regions’ finest<br />

crafts. With the end of royal states, some traditions have died for<br />

want of patronage. Deep appreciation of the remaining arts <strong>is</strong> now<br />

in the hands of a tiny group of art<strong>is</strong>ts, curators, and collectors who<br />

know and appreciate fine crafts, but generally lack the wealth to<br />

keep them going. SEWA’s unfamiliarity with the possibilities of<br />

handmade paper <strong>is</strong> parallel to that of most Indians today. For years,<br />

India’s best contemporary handmade paper has been made in two<br />

centers: the Sri Aurobindo Ashram’s paper mill in Pondicherry,<br />

south of Chennai (formerly Madras); and in Sanganer, an old papermaking<br />

village in Rajasthan. I have heard that some traditional<br />

paper <strong>is</strong> still being made in Sanganer. Apart from that possibility, I<br />

am unaware of any Indian papermakers using traditional materials<br />

or technology, or making burn<strong>is</strong>hed plant papers for miniature<br />

painting, though there would be some market for it. Today’s miniature<br />

art<strong>is</strong>ts paint on the backs of fine old papers, or not so fine,<br />

somewhat old papers. The paintings are skillful, often beautiful,<br />

and merit a reliable source of paper.<br />

In South India’s larger cities and tour<strong>is</strong>t hubs, department<br />

stores and a few specialty shops sell endless varieties of neon-colored,<br />

machine-embroidered, flocked, sequined, and splattered papers<br />

labeled “handmade.” These papers lack entirely the integrity<br />

of material that <strong>is</strong> a hallmark of fine paper. <strong>There</strong> are a tiny number<br />

of shops selling real handmade paper.<br />

How to increase the domestic market for true handmade paper<br />

<strong>is</strong> a challenge. A more elit<strong>is</strong>t approach might include: educating<br />

art<strong>is</strong>ts and upwardly mobile Indians in the aesthetic of fine<br />

winter 2010 • 37

At the SEWA Rural Centre, Ritha, an ass<strong>is</strong>tant to the doctor, prepares an<br />

ayurvedic remedy.<br />

handmade paper; encouraging high-end hotels and restaurants<br />

to use beautiful papers for menus and in-house<br />

brochures; and introducing architects and designers to<br />

alternative uses of paper for wall coverings, lampshades, or<br />

wedding invitations. All of th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> happening to some degree.<br />

Given the growing middle class, the market for such paper <strong>is</strong><br />

increasing, but slowly. It comes back to education.<br />

Another approach <strong>is</strong> to create particular papers for general<br />

use. As one example, Namb<strong>is</strong>an <strong>is</strong> researching the requirements<br />

of a paper that the postal service needs for official<br />

certificates. She hopes such papers might be handmade by<br />

poor women whose families would benefit from the income.<br />

Th<strong>is</strong> too has challenges. Several initiatives to teach homebound<br />

women to process fiber for papermaking projects and,<br />

in some cases, to make paper items for sale have come up<br />

against the women’s lack of initiative or understanding of<br />

the project. Working at home sounds great, but in practice<br />

the women often feel <strong>is</strong>olated and unmotivated. Communal<br />

workshops might reduce <strong>is</strong>olation but that requires funding.<br />

In India’s high-tech boom, funding handicraft may seem like<br />

a step backward. Kerala <strong>is</strong> a rich province with a relatively<br />

high standard of living, but that does not mean the wealth<br />

trickles down, certainly not to the women with whom I<br />

worked. In today’s India, where cash <strong>is</strong> king and connections<br />

to the land are being diluted, maintaining tradition may seem<br />

of questionable value.<br />

In Japan, raw kozo and hemp have long been symbols<br />

of life force and integrity, and used as sacred offerings. Papers<br />

made from these fibers retain cultural resonance beyond<br />

their role as substrate. 3 Despite India’s r<strong>is</strong>ing affluence, deep<br />

ties to the earth remain core to Indian values. In South India,<br />

banana flowers are the carved motifs on temple and palace<br />

ceilings, banana fruits and leaves are sacred offerings, and banana<br />

leaves serve as thali plates. Banana trees, which re-grow quickly from<br />

their roots after being cut, are a symbol of regeneration, similar to<br />

bamboo in East Asia. Coconut, too, has deep spiritual associations<br />

and possibilities for papermaking. Given these earth-based connections<br />

to food and spirituality, it <strong>is</strong> not so farfetched to imagine papers<br />

made from banana and other local fibers having resonance in a new<br />

South Indian paper tradition. Th<strong>is</strong> would be particularly welcome if it<br />

could provide meaningful work for poor women.<br />

In a wider sense, the question of paper’s basic place in a particular<br />

culture may be something to consider as we travel the world teaching<br />

papermaking. If a family owns just one book in the Judeo-Chr<strong>is</strong>tian,<br />

Islamic, or Buddh<strong>is</strong>t culture, it <strong>is</strong> most likely one of the core religious<br />

texts. In contrast, Hindu observance relies largely on Brahmin sacrificial<br />

experts to conduct complex rituals. Though Hindu<strong>is</strong>m has libraries<br />

of sacred writings, these are rarely read at home by lay people.<br />

In South India, paper has been associated more with business than<br />

spirituality. 4 Though th<strong>is</strong> sensitivity <strong>is</strong> not required to impart papermaking<br />

technology, at a subtle level, it may influence how fertile the<br />

ground <strong>is</strong> and the way papermaking <strong>is</strong> taken up.<br />

I am struck by the similarity of my experiences with urban PhD<br />

students and poor rural women. Though the two groups had very<br />

different needs, backgrounds, and motivations, they shared common<br />

ground. 5 Both groups were energized when their curiosity was engaged<br />

and their powers of inquiry sparked. One key to papermaking’s<br />

relevance may lie in grounding and broadening a project’s v<strong>is</strong>ion,<br />

giving teachers, workers, and funders a stake in papermaking not<br />

only as a practical activity but also one with rich cultural connections.<br />

The author w<strong>is</strong>hes to thank Dr. Padma Namb<strong>is</strong>an and Suhag Shirodkar<br />

for their hospitality and hours of stimulating exchange. Shirodkar wrote<br />

on Jenny Pinto’s work with banana fiber paper for Hand <strong>Papermaking</strong><br />

vol. 21, no. 2 (Winter 2006). Currently Pinto <strong>is</strong> researching the possibility<br />

of reviving traditional Indian kagzi paper on her farm in rural Maharashtra.<br />

___________<br />

notes<br />

1. In the north, Muslim kagz<strong>is</strong>, or papermakers, made highly burn<strong>is</strong>hed plant paper<br />

as substrate for Islamic calligraphy and miniature painting. The Brit<strong>is</strong>h successfully<br />

undermined that tradition, flooding the Indian market with their own machine-made<br />

paper and putting Indian papermakers out of work.<br />

2. Sarah Zoutewelle-Morr<strong>is</strong>, “Getting Unstuck,” Letter Arts Review vol. 15, no. 2<br />

(1999).<br />

3. In India, textiles have a parallel metaphorical role to paper in Japan and other<br />

parts of Asia. In many parts of India, the loom, thread, and cloth appear in myths as<br />

symbols for creation and life itself. For more on these ideas, see Dorothy Field, Paper<br />

and Threshold (Ann Arbor, MI: The Legacy Press, 2007).<br />

4. In the West, appreciation for fine handmade paper <strong>is</strong> confined mainly to art<strong>is</strong>ts<br />

and conservators. In our IT-obsessed, supposedly paperless society, we are flooded<br />

with reams of forgettable paper. Th<strong>is</strong> glut lowers any sensitivity we might have had<br />

for paper as a numinous material, even as it ra<strong>is</strong>es the appreciation of a wider public<br />

for “exotic” handmade paper.<br />

5.Their differences in educational background are only a matter of degree. Although<br />

the literacy rate in India as a whole <strong>is</strong> 61%, with women having a lower rate than<br />

men, in Kerala the literacy rate <strong>is</strong> 100% across the board.<br />

38 • hand papermaking