Editor: I. Mallikarjuna Sharma Volume 11: 15-31 March 2015 No. 5-6

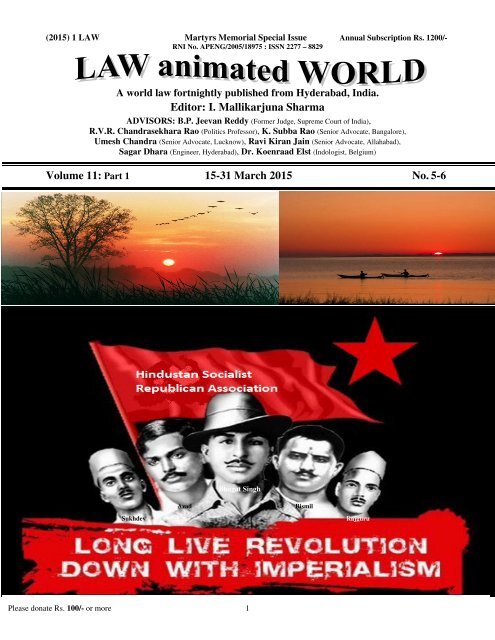

Martyrs memorial special issue of 15-31 March 2015 paying tributes to Bhagat Singh and other comrades.

Martyrs memorial special issue of 15-31 March 2015 paying tributes to Bhagat Singh and other comrades.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

(20<strong>15</strong>) 1 LAW Martyrs Memorial Special Issue Annual Subscription Rs. 1200/-<br />

RNI <strong>No</strong>. APENG/2005/18975 : ISSN 2277 – 8829<br />

A world law fortnightly published from Hyderabad, India.<br />

<strong>Editor</strong>: I. <strong>Mallikarjuna</strong> <strong>Sharma</strong><br />

ADVISORS: B.P. Jeevan Reddy (Former Judge, Supreme Court of India),<br />

R.V.R. Chandrasekhara Rao (Politics Professor), K. Subba Rao (Senior Advocate, Bangalore),<br />

Umesh Chandra (Senior Advocate, Lucknow), Ravi Kiran Jain (Senior Advocate, Allahabad),<br />

Sagar Dhara (Engineer, Hyderabad), Dr. Koenraad Elst (Indologist, Belgium)<br />

<strong>Volume</strong> <strong>11</strong>: Part 1 <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5-6<br />

Bhagat Singh<br />

Sukhdev<br />

Azad<br />

Bismil<br />

Rajguru<br />

Please donate Rs. 100/- or more 1

2 (20<strong>15</strong>) 1 LAW<br />

RAJA BAHADUR VENKATA RAMA REDDY<br />

TELANGANA STATE POLICE ACADEMY<br />

Himayat Sagar, HYDERABAD - 500 091.<br />

Vision:<br />

To transform a “hitherto Law and Order oriented force<br />

into a Service Oriented one”<br />

Mission Statement:<br />

To impart professional training of outstanding quality to<br />

cutting edge level, frontline Police Executives and others<br />

connected with Criminal Justice System to enable them<br />

to serve the community in consonance with law,<br />

understanding its expectation; and respecting rights of<br />

the people in the cause of peace, tranquillity, safety and<br />

security in the society and position the Academy as a<br />

“Centre of Excellence” in the field of Police training.<br />

Director, TSPA<br />

Phone <strong>No</strong>. 040-24593380 Fax: 040-24593201<br />

e-mail: appatoday@gmail.com<br />

Advt.<br />

Law Animated World, <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong><br />

2

(20<strong>15</strong>) 1 LAW Martyrs Memorial Special issue Annual Subscription: Rs. 1200/-<br />

RNI <strong>No</strong>. APENG/2005/18975 : ISSN 2277 - 8829<br />

A world law fortnightly published from Hyderabad, India.<br />

<strong>Editor</strong>: I. <strong>Mallikarjuna</strong> <strong>Sharma</strong><br />

ADVISORS: B.P. Jeevan Reddy (Former Judge, Supreme Court of India),<br />

R.V.R. Chandrasekhara Rao (Politics Professor), K. Subba Rao (Senior Advocate, Bangalore),<br />

Umesh Chandra (Senior Advocate, Lucknow), Ravi Kiran Jain (Senior Advocate, Allahabad),<br />

Sagar Dhara (Engineer, Hyderabad), Dr. Koenraad Elst (Indologist, Belgium).<br />

<strong>Volume</strong> <strong>11</strong>: Part 1 <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong> <strong>No</strong>. 5-6<br />

C O N T E N T S<br />

1. Wishing and waiting for a<br />

New Dawn 3<br />

2. Paruchuri Hanumantha Rao<br />

I.M. <strong>Sharma</strong> 5-10<br />

3. A Historical View of Law,<br />

V.V. Reddy <strong>11</strong>-16<br />

4. The Zeitgeist Movement:<br />

A new train of thought (21) 17-24<br />

5. Autobiography of Martyr<br />

Ramprasad Bismil (1) 25-28<br />

6. Charlie Hebdo: Thinking<br />

New, Rethinking the Old<br />

Rousset Pierre 29-39<br />

7. They are one of us<br />

(l’Humanité editorial) 40<br />

8. Policing Belief: Impact of<br />

Blasphemy Laws on<br />

Human Rights (3) 41-44<br />

9. Historical inevitability or 45-<br />

Electoral corruption?(24) [IMS] 46<br />

10. Shreya Singhal v. Union of<br />

India [IND-SC] [S 66A IT Act] 47-86<br />

<strong>11</strong>. Quake Outcasts v. Minister<br />

for Canterbury Earthquake<br />

Recovery [NZ-SC] (1) 87-142<br />

12. Disengage with Pakistan<br />

completely! (Tarek Fatah) 143-144<br />

13. Legendary Hockey Player<br />

Major Dhyan Chand 145-146<br />

14. Poems, Ashfaq & Bismil 148<br />

<strong>Editor</strong>ial Office: 6-3-1243/<strong>15</strong>6,<br />

M.S. Makta, Opposite Raj Bhavan,<br />

Hyderabad - 500 082; Ph: 23300284<br />

E-mail: mani.bal44@gmail.com.<br />

Plate-making: Sai Likhita Printers,<br />

Hyderabad (Ph: 65545979); Printed at<br />

Pragati Offset Pvt. Ltd., Red Hills,<br />

Hyderabad - 500 004. (Ph: 23380000)<br />

WISHING & WAITING FOR A NEW DAWN<br />

That is what many of us have been doing ever since independence,<br />

especially since the turbulent sixties. This new dawn symbolism could be<br />

interpreted in two ways. One would be to see the entire decades since the<br />

‘transfer of power’ as a long dark night belying the aims and aspirations<br />

of innumerable martyrs of our freedom struggle and leaving but travails<br />

and tears for the people – still waiting for a new dawn that could bring in<br />

the much needed libertarian, welfarist sunlight. Another way of looking<br />

at could be that several dawns have come and gone by ever since but that<br />

we fondly dreamt of has eluded us so far. One set of rulers has come and<br />

gone, giving way to another, which meant not much in practical terms.<br />

Mannerisms and wordings may have changed, even radical democratic<br />

ethos oriented ideologies, laws and schemes might have come up, but yet<br />

real progress has not been made. A simple illustration would be of the<br />

so-called ‘radical and innovative’ Right to Information Act. Some good<br />

might have come about due to it in some places and times, but also many<br />

loopholes there for the authorities to avoid giving the needed information<br />

and make the process more costly and cumbersome for the people.<br />

Perhaps the good old method of petitioning to the public authorities, if<br />

buttressed by strong and quick judicial monitoring, could be more<br />

handy, inexpensive and beneficial to the people at large. Also we see the<br />

power and aura of mammon overwhelming almost all sections of society<br />

like a Macbethian tormenting spirit. The present get-rich-quick-by-anymeans<br />

trend is spelling doom to all the grand dreams of a glorious<br />

egalitarian society based on the mutual aid of a basically good-natured,<br />

well meaning citizenry. We see the basic needs of common people starkly<br />

neglected and the remedial mechanisms including courts reduced to<br />

more and more sloth and inefficiency. The new surge of free market<br />

economy generating an atmosphere of extreme alienation and misery<br />

among the people is ruining all chances of humane social progress. The<br />

only remedy is for the executive and judiciary, with the motto – small is<br />

beautiful and simple is workable – to feel and act as real public servants<br />

and not like lords divine/secular. Only when they begin to use public<br />

transport, live in duly alloted quarters and conduct on-the-spot enquiries<br />

often instead of closing their eyes and ears to the pleas of the common<br />

man, in a word return to the practice of ‘high thinking and plain living’,<br />

can they even think of rooting out the societal ills and it is the duty and<br />

task of we the people to make for such an eventuality by our concerted<br />

efforts and agitations, and usher in the fresh sunrise. ♣♣♣<br />

Please donate Rs. 100/- or more. 3

4 (20<strong>15</strong>) 1 LAW<br />

TO GET A CLEAR INSIGHT INTO EVENTS AT HOME AND ABROAD<br />

READ<br />

MAINSTREAM<br />

Current Affairs Weekly<br />

<strong>Editor</strong>: SUMIT CHAKRAVARTTY<br />

Mainstream provides serious and objective analysis of contemporary developments affecting the nation.<br />

Mainstream offers wide interaction of thought and expression covering divergent viewpoints reflected in the<br />

democratic polity.<br />

Mainstream dissects all aspects of domestic politics, foreign affairs, national economy, problems of ecology<br />

and development, scientific and technological progress.<br />

Mainstream publishes invaluable documents of abiding relevance for global security, regional cooperation and<br />

India’s self-reliant advance.<br />

Get your copy from your<br />

news agent or write to us at<br />

MAINSTREAM<br />

145/1D, Shahpur Jat (First Floor),<br />

(Near Asiad Village), New Delhi - <strong>11</strong>0 049.<br />

All India Distributors:<br />

CENTRAL NEWS AGENCY<br />

4E/4 Jhandewalan Extension, New Delhi - <strong>11</strong>0 055.<br />

Price: Rs. <strong>15</strong>/-<br />

SUBSCRIPTION RATES<br />

INLAND<br />

6 Months 1 Year 2 Years 3 Years Life<br />

Subscription*<br />

FOREIGN<br />

Air Mail<br />

(annual)<br />

Individuals Rs 300 Rs 500 Rs 900 Rs 1200 Rs 8000 Asia $ 85<br />

Institutions - - - Rs 600 Rs 1000 Rs <strong>15</strong>00 Rs 10,000 Europe $ 100<br />

* Life subscription available only in India. America $ 120<br />

Surface Mail<br />

(annual)<br />

All Countries<br />

$ 80<br />

Please send subscription by Cheque/Postal Order/MO to Perspective Publications Private Limited,<br />

145/1D, Shahpur Jat (First Floor), (Near Asiad Village), New Delhi - <strong>11</strong>0 049; Ph: 26497188;<br />

Fax: 26569382; E-mail: mainlineweekly@yahoo.com; Website: www.mainstreamweekly.net. Please add<br />

Rs. 20/- to inland outstation cheques towards bank charges; all remittances to Perspective Publications Private Limited.<br />

Advt.<br />

Law Animated World, <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong><br />

4

PARUCHURI HANUMANTHA RAO<br />

Paruchuri Hanumantha Rao,<br />

son of Narsaiah and Ramamma,<br />

Born 16 January 1924 at Chittarpu,<br />

Divi Taluk, Krishna District.<br />

Died: 2 <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong> at Hyderabad.<br />

[This interview taken in both the ordinary narrative, and answers<br />

to questions, forms.]<br />

* * *<br />

♣ Text of interview by IMS, dated Monday 27-01-2003 at<br />

Hyderabad; From IMS (Ed.), In Retrospect, Vol. 5, Pt. 2,<br />

pp. 465-476; Sri Hanumantha Rao is no longer with us;<br />

expired at about 4 PM on Monday, 2 <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong> at the<br />

age of 91 years; our glowing tributes Sri Hanumantha<br />

Rao garu who was a dedicated communist activist, spent<br />

years in prison including in Cuddalore Jail during the<br />

1948-50 tumultuous period, later took to film and then<br />

printing industry, shined as nobody ordinarily does - all<br />

through his hard work and self-help and built up the great<br />

Pragati Printers, perhaps the <strong>No</strong>. 1 printing press in<br />

Hyderabad which also won many world class awards. He<br />

was always considerate and helpful towards the needs<br />

and demands of the people and especially very friendly<br />

towards all of us socialist roaders. He and Pragati Printers<br />

also helped most of our publications wholeheartedly and<br />

especially contributed and still contribute a lot to the<br />

printing of our world law fortnightly, LAW ANIMATED<br />

WORLD. My profound condolences to his family and<br />

friends; emphases in bold ours - IMS.<br />

- I. <strong>Mallikarjuna</strong> <strong>Sharma</strong> ♣<br />

I was born in a poor peasant family of the<br />

Kamma community. My native village Chittarpu<br />

is at about 16 kilometres from Machilipatnam, in<br />

the Divi Taluk of Krishna District. When the big<br />

deluge devastated the Divi Seema in 1925 I was<br />

just one-year old and now I have completed 79<br />

and running 80. My father had only about 2 ½<br />

acres of dry land but all the same we were not<br />

used to go to labour in others’ fields. The men in<br />

our family used to work hard in the fields but<br />

women used to mainly look after domestic work<br />

and then do any labour at home only but not go to<br />

the fields. My mother used to spin on the Charkha<br />

too in addition to the usual domestic jobs like<br />

peeling off the groundnut shells, piling tobacco<br />

leaves, etc. Gandhiji’s influence was no doubt<br />

behind the spinning but at the same time there<br />

was an economic aspect also to it. In childhood I<br />

used to tend cattle as herdsman and do light<br />

agricultural work too.<br />

A teacher was brought from Angalur, students<br />

were mobilized from door to door in our village<br />

and a night school was set up in which I studied<br />

up to 5th Class Telugu Medium. In<br />

Vakkalagadda, near our village, there was a<br />

school run by Bodi Narayana Rao who used to<br />

teach English also. I went to that school and<br />

joined 7th Class English Medium. Thereafter in<br />

Challapalli High School I studied 8th Class or III<br />

Form. At that time I joined the Scouts movement<br />

and also got acquainted with Chandra Rajeswara<br />

Rao, Challapalli Narayana Rao, Chandra<br />

Ramalingaiah, Kavuri Kutumba Rao, etc. Books<br />

like Gadar Veerulu (Gadar Heroes) and M.N.<br />

Roys’s articles inspired me very much.<br />

In 1936 elections we nationalist minded<br />

children used to go around with placards<br />

requesting people to vote for Gottipati<br />

Brahmaiah, Congress candidate who contested<br />

against the Challapalli Zamindar. The Zamindar<br />

was quite powerful those days and he ultimately<br />

won. But there was also a rumour that Gottipati<br />

5<br />

Law Animated World, <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong>

6 Paruchuri Hanumantha Rao (I.M. <strong>Sharma</strong>) (20<strong>15</strong>) 1 LAW<br />

Brahmaiah took a bribe of Rs. <strong>15</strong>00/- from the<br />

Zamindar and so deliberately did not carry out an<br />

active campaign; I do not know how far it was<br />

really true. By the time I came to 5 th Form, I read<br />

life histories of Bhagat Singh, Alluri Sitarama<br />

Raju and some of Roy’s books. I was very much<br />

inspired by Roy’s life history. However, there was<br />

no family tradition or influence at all on me which<br />

inspired me into the national movement; none among<br />

our relatives exerted any impact towards<br />

nationalism. While I was studying 5 th Form, a<br />

classmate of mine had written the slogan<br />

Swatantra Bharat ki Jai on the classroom wall.<br />

The class teacher and Head Master saw that and<br />

got enraged. I was the Class Monitor and so they<br />

asked me to divulge the name of the student who<br />

wrote that slogan. I knew him but since my<br />

revelation would ruin his career I refused to<br />

divulge and then the enraged school authorities<br />

expelled me from the school giving me a transfer<br />

certificate. I then joined the Hindu High School at<br />

Machilipatnam. I worked in the All India Students<br />

Federation (AISF) unit in Machilipatnam and<br />

joined the Praja Natya Mandali. I used to act on<br />

stage and also sing songs well. I had even got<br />

some prizes for singing some national songs on<br />

the theme of Royalaseema Famine.<br />

Later I joined a communist party cell in the<br />

company of G. Srihari and Chalapathi Rao. In<br />

1941 June the Germans attacked the Soviet Union<br />

which development gave rise to a radical change<br />

in the War situation. By that time I had written<br />

but failed in my S.S.L.C. Examinations. With the<br />

German attack on the Soviet Union the party<br />

policy also began to change and the People's War<br />

line was adopted by the end of 1941. In the<br />

summer of 1942 a big Anti-Fascist Camp was<br />

held under the auspices of the communist party at<br />

Kodali. I wrote my S.S.L.C. Examinations for a<br />

second time and afterwards went to participate in<br />

this Anti-Fascist Camp along with Mikkilineni<br />

Radhakrishna Murthy, Perumallu, Koganti<br />

Gopalakrishnaiah and Tatineni Prakasa Rao and<br />

others. Later the S.S.L.C. Results were published<br />

and I passed this time. Thereafter I joined the<br />

Intermediate in the Hindu College. In those days<br />

I was a good sportsman and used to play<br />

Basketball, Volleyball, Badminton, etc. quite well<br />

and this talent helped me in my academic career<br />

too. After my Intermediate I became University<br />

player in Basketball. In Intermediate also there<br />

was a two years gap in my studies. The reason<br />

was that in 1942 we students actively participated<br />

in the Quit India movement no matter whether we<br />

belonged to the Communist Party or Congress. So<br />

once I failed in Intermediate I year or so. I had<br />

taken Biology as one of my subjects and could<br />

not study properly. Then came the 1943 Bengal<br />

Famine and I had actively taken part in the<br />

campaign to collect funds for famine relief. We<br />

played several dramas and collected subscriptions<br />

and donations. All this we did in Bandar only.<br />

I played the role of a Shetty (Baniya - Komati) in<br />

one drama and all spectators who saw my role<br />

were very much impressed and even the Komatis<br />

of the town thought I also belonged to their caste;<br />

and came to me and asked whether I was also a<br />

Komati. Though my second year Intermediate<br />

Studies in the College were completed by 1944,<br />

since I failed in examinations, there was repeated<br />

backlog. And in 1946 I had to take an active part<br />

in election campaigns. As such it was only in<br />

September 1947 that I wrote the last<br />

supplementary examination to complete the<br />

Intermediate Course and immediately afterwards<br />

went to Bombay. The real purpose was to try for<br />

B.Sc. (Agriculture) seat in some college there.<br />

But actually I joined the Indian People’s Theatre<br />

(IPT) at Bombay. Durga Khote was the President<br />

and Balraj Sahani, K.A. Abbas were prominent<br />

office-bearers in IPT and I became acquainted<br />

with all of them. Since I was a member of the<br />

communist party and IPT was a front<br />

organization of the communist party, there was a<br />

party cell also in the IPT to direct the actual<br />

functioning of the front organization. Parvati<br />

Krishnan was also a party member associated<br />

with IPT. Mohammed Safdar (who later went to<br />

Pakistan), Balraj Sahani, one Suryam belonging to<br />

Veerullapadu (a wonderful singer), one dancer (I am<br />

not able to recollect his name now) and myself were<br />

in one party cell within IPT. Sailendra was also<br />

Law Animated World, <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong> 6

(20<strong>15</strong>) 1 LAW Paruchuri Hanumantha Rao (I.M. <strong>Sharma</strong>) 7<br />

associated with our IPT. Actually he used to work<br />

in the Western Railway and inspired by our<br />

activities he wrote a nice and inspiring song. Raj<br />

Kapoor used to occasionally visit us and watch<br />

our activities and he very much liked that song<br />

and then took Sailendra to write songs for his<br />

films. Gradually under Raj Kapoor’s patronage,<br />

Sailendra became a great poet and writer of<br />

wonderful film songs. Raj Kapoor was never a<br />

member of the communist party but he was no doubt a<br />

sympathizer. That is why we can find the social<br />

consciousness against exploitation and oppression and<br />

urge for betterment of society very much manifest in his<br />

many films. There were about 2 lakh Telugu<br />

workers in Bombay and when the elections to<br />

Bombay Municipal Corporation were to be held,<br />

three of us – Veerullapadu Suryam, another<br />

person and myself formed a team of Telugu<br />

balladeers and campaigned for the communist<br />

candidates – Dange and others among the Telugu<br />

workers through our Burra Kathas. Dange had<br />

won as Municipal Corporator in those elections.<br />

However, I had no personal acquaintance with<br />

Dange. But I knew about him as a militant trade<br />

union and very learned communist leader. When<br />

his daughter Roza Deshpande was just a child<br />

once during a picketing before the Gates of a<br />

Factory he brought here and made her lie down<br />

across the Gate with himself and other workers<br />

also staging a sit-in as part of a militant dharna.<br />

Prior to going to Bombay, there were celebrations<br />

of the First Independence Day in Machilipatnam<br />

on <strong>15</strong> August 1947. At that time I was in<br />

Machilipatnam itself but though the communist<br />

party participated in the celebrations I personally<br />

refused to participate. Though I was specifically<br />

called by comrades to come and participate I did<br />

not go and replied to them that since anyway even<br />

the party considers it as a mere transfer of power and I<br />

consider it as a fake independence I saw no reason in<br />

celebrating the occasion. But the then leaders in the<br />

party at Machilipatnam, M. Srihari, V. Rama Rao<br />

and others did participate. In Machilipatnam we<br />

communist students generally used to stay<br />

together in rented houses and set up common<br />

messes. At first we about 10 progressive students<br />

established one Pragati Mess at Frenchpet and<br />

later only two of us - another comrade and I,<br />

began to stay together at Frenchpet. Communist<br />

leaders like Chandra Rajeswara Rao, Challapalli<br />

Narayana Rao and others used to be<br />

accommodated in our messes as and when the<br />

need arose.<br />

While I was at Bombay the entire Punjab was<br />

burning and suffering with cruel and<br />

unprecedented communal riots. In that<br />

background Sailendra had written a really moving<br />

song – Jalta hai Punjab Jalta hai, Bhagat Singh ka<br />

aankhon ka tara, Jalta hai Punjab Jalta hai!, etc.<br />

It became quite popular in those days. Kalyani,<br />

wife of Mohan Kumara Mangalam, was also a<br />

member in IPT. I also very much remember the<br />

situation in Bombay on the day of Gandhiji’s<br />

assassination, that is 30 January 1948.<br />

Immediately as the news of Gandhi’s<br />

assassination was broadcast there was great<br />

tension in the whole city and merchants and<br />

shopkeepers spontaneously downed the shutters<br />

and closed their establishments. There was a<br />

complete hartal in the city and an eerie silence.<br />

Another comrade and I were stranded in the midst<br />

of the city at that time and there was no public<br />

transport at all. The identity and religion of the<br />

assailant was not yet known clearly. Dadar had a<br />

lot of Muslim population and there was every<br />

danger of communal riots breaking down any<br />

moment if the assailant were to be a Muslim by<br />

any chance. In such a situation we walked all the<br />

way from Prince’s street to Kamatipura and later<br />

took shelter in a party office of ours. Luckily<br />

there were no communal riots since the identity<br />

of the assailant was ascertained as a Hindu<br />

fanatic. I did not pursue the B.Sc. (Agri) Course<br />

in Bombay but took my T.C. and came back to<br />

Machilipatnam in <strong>March</strong>-April 1948. Later,<br />

I joined the B.A. course in Hindu College,<br />

Machilipatnam. Dandamudi Subba Rao (in later<br />

days shot dead by the police) and Raavi Subba<br />

Rao (later became a famous Advocate) also joined<br />

there along with me. In those days other<br />

comrades and I were fully supporting the militant<br />

insurrectionary line of the party, especially the<br />

Telangana Armed Struggle. As against the Nizam<br />

7<br />

Law Animated World, <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong>

8 Paruchuri Hanumantha Rao (I.M. <strong>Sharma</strong>) (20<strong>15</strong>) 1 LAW<br />

Rule we had propagated a lot by way of songs,<br />

sloganeering, etc. in Machilipatnam. Chalasani<br />

Venkateswar Rao and I were staying together in a<br />

room at Frenchpet in those days and some<br />

underground leaders of the party, especially<br />

Chalasani Srinivasa Rao, used to come and take<br />

shelter in our room. This Chalasani Srinivasa Rao<br />

was later shot dead by the police. Once the police<br />

raided our room and arrested both of us and kept<br />

us in sub-jail. After 3 days we got released on<br />

bail. Then some discussion went on inside the<br />

party as to what reply we accused should give if<br />

we were asked by the judicial officers as to our<br />

political identity – should we say we were<br />

communists or not. At last it was decided that we<br />

should own up our real political identity and say<br />

we were communists. Accordingly when at the<br />

trial of our case Chalasani Venkateswar Rao and I<br />

replied in the affirmative to the question as to<br />

whether we were communists, we were<br />

immediately put under detention and sent to<br />

Rajahmundry Central Jail where we were kept for<br />

3-4 months. Later we were transferred to<br />

Cuddalore Camp Jail where in all 350-400<br />

communist prisoners were confined. Kodali<br />

Satyanarayana, Katragadda Venkata Narayana<br />

Rao, Tammareddy Satyanarayana and others<br />

were there along with us. In the jail all of us<br />

communist detenues followed the then party<br />

policy and adopted militant tactics. This led to<br />

great friction with the jail authorities and I think<br />

when we violently resisted being locked up in<br />

nighttime a serious disturbance occurred and the<br />

armed police attacked us severely. Police resorted<br />

to firing also after first lathi-charging and then<br />

bayoneting. One Sitarama Rao, a peasant leader,<br />

was bayoneted to death. In the ensuing firings<br />

also one or two comrades died and several<br />

injured. At that time I was just beside the<br />

bayoneted peasant leader and immediately lied<br />

down and rolling my body over for a distance<br />

safely escaped from police clutches. Though<br />

Katragadda Venkata Narayana Rao, Tammareddy<br />

Satyanarayana, Kotaiah and others were injured,<br />

I was not. It was due to that injury that K.V.<br />

Narayana Rao became lame and Tammareddy<br />

Satyanarayana received a bullet injury in his<br />

hand. At last in the evening at 6 P.M. we<br />

communist detenues surrendered like defeated<br />

soldiers in a battle. At that time I fully supported<br />

and followed the Ranadive Line.<br />

In Cuddalore Camp Jail political classes used to<br />

be held daily and we received good education in<br />

History, Soviet Socialist Constitution, Political<br />

Economy and languages and we built up a good<br />

library. It was like a university to us. Comrade<br />

Vijayakumar from Vizag, Vallabha Rao, Tatineni<br />

Chalapati Rao, Koganti Gopalakrishnaiah were in<br />

our cultural team also and we used to stage some<br />

plays and sing revolutionary songs. Once I even<br />

acted in the roles of Comrades A.K. Gopalan and<br />

M.R. Venkatraman.<br />

There were intense discussions among us<br />

detenues as to whether it was proper to continue<br />

the armed struggle or withdrawal was necessary<br />

and inevitable. Some comrades like Koganti<br />

Gopalakrishnaiah could not withstand the severe<br />

repression by jail authorities and opted to get<br />

transferred to a separate camp. At this the<br />

extremists among us used to scold and abuse<br />

them but in such cases other comrades and I used<br />

to intervene and persuade the extremists not to be<br />

too hostile towards our erstwhile friends. There<br />

were comrades who stood fearless and unmoved<br />

at any amount of repression but there were also<br />

comrades with weak sentiments – some of them<br />

used to even weep aloud on hearing sentimental<br />

tragic stories in the Balanandam programme<br />

broadcast over All India Radio. Once 200 of us<br />

detenues went on an indefinite hunger strike on<br />

some important demands but about 50 withdrew<br />

in the middle. On the advice of Dr. Chelikani<br />

Rama Rao we all had taken one glass of jaggery<br />

solution (panakam) before starting the fast and<br />

that did a lot of good to our health condition.<br />

I continued the fast for 30 days. But later seeing no<br />

possibility of any amount of success we ourselves<br />

gradually stopped fasting. But we all got so weak<br />

and emaciated due to that prolonged fast that it<br />

took nearly one month for us to regain our former<br />

energy and strength. Ultimately, after 3 years of<br />

Law Animated World, <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong> 8

(20<strong>15</strong>) 1 LAW Paruchuri Hanumantha Rao (I.M. <strong>Sharma</strong>) 9<br />

detention, we were released sometime in 1951.<br />

I worked as correspondent for Vishalandhra at<br />

Madras for a long time after independence. I very<br />

much know about the fasting of Potti Sriramulu<br />

since I used to visit his camp and report the<br />

details to Vishalandhra. Bulusu Sambamurthy was<br />

seen there many times encouraging Sriramulu to<br />

continue his fast to death. He himself was eating fruits<br />

and talking when Sriramulu was fasting for days<br />

together which struck to me as somewhat odd.<br />

Sambamurthy himself refused to fast but used to<br />

say to Sriramulu who was much younger than<br />

him: “Hi, Sriramulu, you don’t have a wife or<br />

children. So continue to fight and die for the<br />

cause. You will earn a good name.” On the last<br />

day of the fast Chandra Rajeswara Rao and I<br />

went together to visit Sriramulu. However, it<br />

should be said to the credit of Sriramulu that he<br />

was always quite firm and never wavered in his<br />

determination to fast unto death.<br />

As for the controversy that the communists did<br />

not press for inclusion of Madras in Andhra Province,<br />

which was the chief demand of Potti Sriramulu, I can<br />

only say that it was an impractical demand. Already<br />

Madras was an overwhelmingly Tamilian<br />

majority city and though there was a talk of<br />

partition of Madras too at one time the Tamilians<br />

would never have agreed to it. On this aspect<br />

Prakasam Pantulu, Tenneti Viswanadham and us<br />

communists jointly held a big public meeting at<br />

Madras in the premises of Velagapudi<br />

Ramakrishna’s factory. There was no consensus<br />

in it but in their speeches Prakasam and<br />

Viswanatham declared that a resolution calling<br />

for the formation of Andhra State including<br />

Madras in it was passed and then quickly left the<br />

place. All people thought that the meeting was<br />

over and began to disperse. But Chandra<br />

Rajeswara Rao announced from the dais that the<br />

meeting was far from over, no consensus<br />

resolution was passed and called the people back.<br />

Narla Venkateswar Rao was asked to preside the<br />

meeting and Nagi Reddy gave a wonderful<br />

speech for about one hour patiently explaining<br />

the entire situation and ultimately a resolution calling<br />

for the immediate formation of the Andhra Province<br />

with al the undisputed areas included in it was passed.<br />

I think it was a wise resolution. I am of the<br />

opinion that it was our mistake to have given up<br />

Bellary, which was mainly a Telugu city, and not<br />

Madras, which was even then mainly a Tamil<br />

city. Later a huge public meeting was held at Law<br />

College Grounds, Madras on the issue of Andhra<br />

Province to which leaders from all parties were<br />

invited. There was a very tense and electric<br />

atmosphere and if anybody were to oppose<br />

inclusion of Madras in Andhra Province the<br />

audience would have thrown stones, etc.<br />

Velagapudi Ramakrishna from Justice Party,<br />

some Congress party leaders, Tenneti<br />

Viswanadham of Praja Party, Gowthu Latchanna<br />

and Tarimela Nagi Reddy from our communist<br />

party addressed the meeting. In that surcharged<br />

meeting Nagi Reddy spoke excellently for one<br />

hour in chaste Royalaseema Telugu without<br />

openly asking us to give up Madras but hinting<br />

that we should not insist on its inclusion, etc. and<br />

drew applause from the crowd.<br />

After the defeat in 1955 General Elections to<br />

the Andhra Assembly our Communist Party of<br />

India got very much disheartened and the entire<br />

apparatus of fulltime party workers was almost<br />

disbanded. Every worker was asked to look after<br />

his own livelihood and then if it was possible do<br />

free service for the party too. In such a situation I<br />

happened to enter the cine field for a time.<br />

Varalakshmi, C.V.R. Prasad, Kondepudi<br />

Lakshminarayana, and some others also entered<br />

the film arena at that time. Until then though I<br />

had taken part in IPT and possessed some cultural<br />

talents I was largely in the student organizational<br />

field or journalistic field as correspondent for<br />

Vishalandhra. Yarlagadda Ramakrishna Prasad,<br />

brother of Challapalli Zamindar, was somewhat<br />

friendly and sympathetic to us and had some<br />

progressive ideas. Of course he was mainly a<br />

businessman only but had good contacts and<br />

rapport with S.V. Narsaiah (SVK Prasad’s<br />

brother) and used to help our AISF activities. He<br />

wanted to establish a film studio in Hyderabad<br />

after the formation of Vishalandhra (Andhra<br />

Pradesh). Thus was born the Sarathi Studio at<br />

Amirpet, Hyderabad and I was asked to look after<br />

9<br />

Law Animated World, <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong>

10 Paruchuri Hanumantha Rao (I.M. <strong>Sharma</strong>) (20<strong>15</strong>) 1 LAW<br />

its management at the ground level though<br />

Tammareddy Krishnamurthy was the designated<br />

Manager. So I resigned from Vishalandhra, came<br />

to Hyderabad to look after the construction and<br />

running of Sarathi Studio. The decision was taken<br />

in 1957 and I think by 1962 or so we had<br />

produced about 30 films in the Studio. We had a<br />

mind to encourage new faces to act as heroes and<br />

heroines in progressive type of films, which were<br />

to be made at a low budget. For this purpose we<br />

used to go to different colleges in the Twin Cities<br />

and attend their cultural functions, interact with<br />

the cultural troupes in the city, etc. to identify<br />

potential talents. We had produced a good film<br />

Maa Inti Mahalakshmi in the direction of which I<br />

also played a part. I attended the Nizam College<br />

Annual Day functions in search of new faces. We<br />

brought Prabhakar Reddy into the film industry.<br />

Dasarathi Krishnamacharya, the famous poet,<br />

was also brought into the cine field and he wrote<br />

some very good songs. Under the banner of<br />

Navayuga Pictures many good films were made.<br />

Later I quit from the cine field and started Pragati<br />

Press on 1 September 1962 in a small way. It was<br />

a letter composing and treadle printing press with<br />

a handful of workers and in the initial days my<br />

brother-in-law Nilakantheswar Rao contributed<br />

much in its management. This enterprise proved<br />

very lucky for us and by the dint of hard work<br />

and innovative methods we developed it bit by bit<br />

over the decades and now it is one of the best<br />

printing presses in entire Asia. Our press has now<br />

the latest technology at its command and my two<br />

sons, Narendra and Mahendra, the new<br />

generation boys, have taken the press to<br />

unprecedented heights. <strong>No</strong>w we are participating<br />

in exhibitions all over the world and have got<br />

orders from various places in the world. We use<br />

Internet frequently in our dealings. Punctuality,<br />

promptitude and neat and exquisite printing are<br />

our hallmarks and the one thing, which all<br />

customers can find in us, is RELIANCE. They<br />

can give us a job and forget about it. It will be<br />

carried out according to schedule and to their<br />

satisfaction and the product would reach them in<br />

time, if necessary at their doorstep. And the cost<br />

we charge is quite reasonable too. Recently we<br />

had participated in a printing exhibition in<br />

America in which our Stall became a cynosure.<br />

But for the 9-<strong>11</strong> terror incident, which occurred at<br />

that time resulting in quick disbanding of the<br />

Exhibition, we could have secured a number of<br />

orders even from USA. I never imagined that our<br />

Press would grow to such great heights and I am<br />

really proud of it – especially of my two sons and<br />

the faithful and hardworking staff and workers.<br />

Earning money has never been my main<br />

consideration. What I always desired was<br />

satisfaction from success of my plans and toil.<br />

What I could not achieve in the political field I did<br />

achieve in the printing field.<br />

I know C.K. Narayana Reddy very well and<br />

I played a prominent part in his marriage in<br />

arranging him a match - Jayaprada, a girl related<br />

to us. Tapi Dharma Rao was the elder who<br />

performed their marriage. C.K. too entered the<br />

printing field round around the same time (as we<br />

did) but was not successful. But he published<br />

some good books and contributed to the success<br />

of the Hyderabad Book Trust, which is now<br />

running fairly well. I also know Ramoji Rao well<br />

all through his days of thick and thin and have<br />

always been helpful to him, especially his<br />

Eenadu. Even now I have good rapport with him.<br />

I still believe in the ideal and ideology of Socialism and<br />

think there is no better alternative to it for human<br />

welfare. I am not satisfied with the policies and working<br />

of the various communist parties and groups though.<br />

I desire a unity and vigour in the communist movement<br />

in our country.<br />

* * * * *<br />

Read and subscribe to:<br />

Analytical<br />

MONTHLY REVIEW<br />

<strong>Editor</strong>: SUBHAS AIKAT<br />

Annual subscription : Rs. 350/-<br />

Contact for details:<br />

CORNERSTONE PUBLICATIONS,<br />

Ramesh Dutta Sarani, P.O. Hijli Cooperative,<br />

KHARAGPUR - 721 306 (W.B.)<br />

Law Animated World, <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong> 10

A law may be formal or informal. An informal law<br />

may be an outcome of customs and traditions, accepted<br />

by the society and followed by the people – not<br />

enforced by a formal authority from above but<br />

from within. If any one violates the informal law<br />

he may be outcast. This fear of ostracization itself<br />

has the force of enforcement. On the other hand,<br />

the formal law is the official recognition of a social fact,<br />

enacted by a legislature and enforced by the state<br />

apparatus – the courts and the police. Therefore,<br />

the existence of a state becomes a prerequisite for the<br />

being and enforcement of law.<br />

Origin of the State:<br />

In the prehistory of mankind, some thousands<br />

of years before the Christian era, there existed<br />

what can be called a primitive communist society.<br />

In this society, land and other means of<br />

production were held in common; therefore,<br />

collective labor was applied in production, and<br />

the produce was shared by the families according<br />

to their needs.<br />

But due to the crude nature of the instruments<br />

of production, and labor, the production was very<br />

low – often insufficient to sustain life even.<br />

Hunger prevailed and population began to<br />

decline. At this juncture, some families had, by<br />

force or connivance, ‘stole’ the common property<br />

and transformed it into their private domain. Thus<br />

a new society was born – it was a slave society in<br />

which private property was the [all-embracing]<br />

economic base [– so much so that slave laborers<br />

were mere chattel of the slave-owners]. As such,<br />

Pierre Joseph Proudhon had aptly remarked:<br />

“Property is theft – but it gives power.” 1<br />

♣ Sri V.V. Reddy, Retd. Professor of Economics, REC {now<br />

NIT}, Warangal; duly edited; emphases in bold ours - IMS.<br />

1<br />

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (<strong>15</strong> January 1809 – 19 January 1865),<br />

a French politician, founder of mutualist philosophy,<br />

probably the first person to declare himself an anarchist<br />

and so considered by many as ‘father of anarchism’,<br />

a member of the French Parliament after the 1848<br />

revolution, thereafter referred to himself as a federalist.<br />

A HISTORICAL VIEW OF LAW<br />

- V.V. Reddy ♣<br />

When property was monopolized by some, it<br />

meant others were denied of it. Therefore, slave<br />

society was split into have-nots – the slaves, and<br />

haves – the slave-masters; or, to put in another<br />

way, into antagonistic classes. In order to keep<br />

the slaves languishing in slavery, a coercive<br />

apparatus had become necessary. This apparatus<br />

came to be known as the State, with functions to<br />

safeguard the interests of the entire propertied i.e.<br />

the slave masters. 2<br />

A Greek philosopher by name Cleon (400<br />

B.C.) is said to have defined: “Democracy is of<br />

the people, by the people and for the people.” 3<br />

But in Greco-Roman societies by ‘people’ were<br />

meant only the ‘citizens’ i.e. the slave-masters,<br />

for slaves were only chattel to serve their masters.<br />

Aristotle (B.C. 384-322), considered a genius of<br />

the ancient world, wrote: “For that some should<br />

rule and others be ruled is a thing not only<br />

necessary, but expedient; from the hour of their<br />

birth, some are marked out for subjection, others<br />

for rule…” 4 As such the rulers have a self-interest<br />

His bitter comment on private property – ‘Property is<br />

theft!’ – Louis Blanc claimed, and Marx repeated, was<br />

taken from J.P. Brissot de Warville, a Girondin during the<br />

Great French Revolution. It is noteworthy that Proudhon<br />

himself stated: “Property is theft! That is the war-cry of<br />

’93!” and then said: “Property is Robbery!” However, it<br />

is undisputed that young Marx did greatly admire<br />

Proudhon and his seminal work ‘What is Property?’, and<br />

commended – “<strong>No</strong>t only does Proudhon write in the<br />

interest of the proletarians, he is himself a proletarian,<br />

an ouvrier. His work is a scientific manifesto of the<br />

French proletariat” – though later he disagreed with<br />

Proudhon's anarchism and published caustic criticisms of<br />

Proudhon - he wrote The Poverty of Philosophy in<br />

refutation of Proudhon's The Philosophy of Poverty.<br />

2 Frederick Engels, The Origin of Family, Private Property<br />

and the State, 1894.<br />

3 A. Brewer, Marxist Theory of Imperialism:<br />

A Critical Study, 1972, p. 56.<br />

4 Aristotle, Politics, tr: Benjamin Jowett,<br />

Kitchener, 1999, Book 1, Part V, p. 8.<br />

Aristotle<br />

<strong>11</strong><br />

Law Animated World, <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong>

12 A Historical View of Law (V.V. Reddy) (20<strong>15</strong>) 1 LAW<br />

in property, the source of wealth. Only citizens<br />

were eligible to elect the law-making body,<br />

namely, the Senate. In other words, democracy in<br />

the slave society was only democracy for a few.<br />

Yet, the Greco-Roman societies made<br />

tremendous progress in economic development<br />

by using slave labour. Besides the Pyramids in<br />

Egypt, the Olympia in Rome, Gothic Cathedrals,<br />

Roman aqueducts (irrigation channels) stand for<br />

exemplary engineering skills. With the aqueducts,<br />

agriculture became the main occupation, and it<br />

was supplemented by animal husbandry. To assist<br />

agricultural production metallic tool-making<br />

developed;, silk-clothing and carpet weaving for<br />

the sake of slave-masters made a headway; and<br />

the army was equipped with deadly metallic<br />

weapons. More important was the growth of<br />

exchanges between the town and the country,<br />

specially accompanied by the growth of various<br />

handicrafts in towns. This meant that an urban<br />

civilization had emerged for the first time – that<br />

only in the slave society.<br />

One may wonder as to how the replacement of<br />

collective [community] property by private<br />

property could achieve economic progress. This<br />

is so because when a new mode of production<br />

negates the old and outdated one, progress does<br />

take place. Thus, when the slave mode of<br />

production was replaced by the feudal mode,<br />

further progress was made, and when the<br />

capitalist mode of production ousted the feudal<br />

mode, productive forces have grow sky-high.<br />

Accordingly, new laws are made with the old<br />

ones repealed or amended in order to aid and<br />

assist the new mode of production.<br />

Feudal Society: In spite of the economic progress<br />

of the Slave society, beyond a point, became a<br />

hurdle for the further advance of society. The<br />

slaves, who were the actual producers, had no<br />

material incentives in production. The whole<br />

product, save that necessary for their subsistence,<br />

was appropriated by the slave masters. Therefore,<br />

slave revolts became frequent and that despite an<br />

oppressive State. The one led by Spartacus 5<br />

finally caused the gradual replacement of outright<br />

slavery with debt bondage or serfdom and a new<br />

mode of production, the feudal system of society,<br />

came in its place.<br />

Death of Spartacus by Herman Voggel (1882)<br />

In the new society the slave-masters became<br />

landlords, and the slaves, peasant serfs. The<br />

peasants were allotted small plots of land for their<br />

own cultivation and subsistence, and in lieu had<br />

to work free on the estates of their lords for<br />

certain days in a week. This mode of production<br />

was better than the slave mode. For, the whole<br />

produce raised by the peasant was retained for<br />

himself, and provided sufficient incentive to work<br />

hard to raise the crop yield. The lord got his<br />

estate tilled by the peasants free of charge.<br />

5<br />

Spartacus (<strong>11</strong>1–71 BC), a Thracian gladiator, one of<br />

the escaped slave leaders in the Third Servile War, a<br />

major slave uprising against the Roman Republic.<br />

This, interpreted by some as an example of oppressed<br />

people fighting for their freedom against a slaveowning<br />

oligarchy, has been an inspiration to many<br />

political thinkers, and featured in literature, television,<br />

and film [Howard Fast’s novel Spartacus makes him<br />

immortal in the progressive circles]. Neither any historical<br />

account nor any of the actions of the rebel leaders<br />

indicate that the rebellion was specifically aimed at<br />

ending slavery [ref: Wikipedia]. However, its long-term<br />

impact has been significant weakening of the slave<br />

system and ushering in of the serfdom or feudal mode<br />

of society. (Pic: Spartacus’ statue at Louvre Museum→)<br />

Law Animated World, <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong> 12

(20<strong>15</strong>) 1 LAW A Historical View of Law (V.V. Reddy) 13<br />

The feudal society inherited the legacy of the<br />

slave state, with the difference that there was no<br />

elected law-making body, except a hereditary<br />

one, e.g. the House of Lords in England. But in<br />

practice the King or the Emperor, was the sole<br />

authority to make or unmake the law by his so-called<br />

Divine Rights of the king. In effect, this amounted to<br />

autocracy. In spite of it, feudal mode of<br />

production made an advance in the growth of<br />

productive forces. Crafts and trades developed in<br />

cities and towns, and exchange of products<br />

between the town and the country had grown<br />

through money, which by then became a common<br />

medium of exchange. To put it in economic<br />

terminology, products became commodities, that<br />

is to say, goods to be bought and sold, and a<br />

market was formed. Along with these exchanges,<br />

the peasant serfs were transformed into tenant<br />

farmers, even on the estates, and the farmers paid<br />

a fixed rent (quit rent) to the landlords, usually<br />

two-thirds of the crop yields. Such high rents<br />

became a burden on the peasants. Frequent crop<br />

failures on account of the vagaries of nature and<br />

climate made the peasants rent defaulters. This<br />

forced some of the peasants to desert their lords<br />

and run away to the towns, and the landlords in<br />

turn run to the moneylenders. And, when<br />

landlords defaulted, they had to surrender their<br />

estates to their creditors. In turn, the creditors<br />

sold away the lands prosperous tenant farmers.<br />

Thus emerged a stratum of independent landowning<br />

peasants, which marked the decay of feudalism.<br />

BIRTH OF A NEW CLASS: Meanwhile, the<br />

traditional home-based crafts had developed into<br />

workshops. The workers were hired from urban<br />

poor and the runaway tenant farmers. The<br />

commodities were sold and raw materials<br />

purchased by a crop of traders who were paid a<br />

commission for their services. 6 In course of time<br />

the workshops became manufactories, and traders<br />

set up their network of sales and purchases. Thus<br />

was born a new class, known in the French as<br />

‘bourgeoisie’ – a middle class, an independent<br />

6 Maurice Dobb, Studies in the Development of Capitalism,<br />

1936, p. 212.<br />

class between the landlords and the peasants. As<br />

the bourgeoisie became economically strong, they<br />

began to demand equal rights on par with the<br />

aristocracy, abolition of tax exemption to the<br />

landlords, removal of restrictions on trade,<br />

including foreign trade. These demands were<br />

supported by the mercantilists, [forming] the first<br />

school of economic thought. Its spokesperson<br />

Thomas Munn (<strong>15</strong>71-1641 A.D.) wrote: “Although<br />

a kingdom may receive gifts in gold from others,<br />

but they are of small consideration. The ordinary<br />

means to increase our treasure is to expand our<br />

trade with foreign countries. This will also help<br />

the growth of home production, and increase tax<br />

revenue.” 7 Hard pressed for more revenue,<br />

England, and some European states, removed<br />

restrictions on home and foreign trade to meet the<br />

demands of the rising bourgeoisie for a free trade<br />

and enterprise. Some countries like England and<br />

Netherlands had set up trading companies to trade<br />

with foreign countries e.g. the [British]East India<br />

Company and the Dutch East India Company.<br />

<strong>No</strong>t satisfied with free trade, the bourgeoisie set its<br />

sight on state power. The Glorious Revolution in<br />

England (1688) had transferred all the powers of<br />

the Emperor to the House of Commons, and the<br />

king-emperor was made a titular head of state.<br />

The French Revolution (1789) overthrew the rule<br />

of the feudal aristocracy, and opened a new epoch<br />

of capitalism, whose economic philosophy is free<br />

trade, free enterprise and free competition. This<br />

philosophy helped the growth of productive<br />

forces to a level never known before. Even the<br />

Communist Manifesto (1848) written by Marx<br />

and Engels had to acknowledge: “The<br />

bourgeoisie, historically, has played a most<br />

revolutionary part. …The bourgeoisie, during its<br />

rule of scarce one hundred years, has created<br />

more massive and more colossal productive<br />

forces than have all preceding generations<br />

together.” 8 To put it metaphorically, some of the<br />

wonders of the world like the Pyramids and the<br />

7 Quoted by Eric Roll, History of Economic Thought, 1934,<br />

p. <strong>11</strong>6.<br />

8 Marx and Engels, The Communist Manifesto, pp. <strong>15</strong>-17.<br />

13<br />

Law Animated World, <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong>

14 A Historical View of Law (V.V. Reddy) (20<strong>15</strong>) 1 LAW<br />

Taj Mahal pale away before the steam engine and<br />

the electric motor. Therefore, it was no surprise<br />

when man set his foot on the moon by the 70s of<br />

the 20 th century. All these achievements are due<br />

to harnessing of the forces of nature by human<br />

labour – both physical and mental – and molding<br />

it into a super-technology. Alas, today technology<br />

has also become a private property through intellectual<br />

property rights. That is, as said already, what the<br />

law does is only the official recognition of the fact.<br />

LEGITIMIZATION OF LAWS: In order to legitimize<br />

the existing laws, periodic elections are held to<br />

the law-making bodies. However, in the words of<br />

Prof. G.K. Galbraith, “In the USA people have<br />

votes, but only the rich vote, as the poor is<br />

indifferent because they are worried of their<br />

jobs.” 9 This is true, because not many American<br />

Presidents were elected with a majority of<br />

popular vote. Still, the laws, both old and new,<br />

become legitimized. Then, what is the nature of<br />

the legislature, a senate or a parliament? Let us<br />

listen to the well-known American journalist,<br />

McChesney: “Throughout the capitalist era, whether<br />

in the United States of America or elsewhere, so<br />

to speak, power has been ‘bought’. <strong>No</strong>t for nothing,<br />

the U.S. Senate was described as a rich man’s<br />

club when there were no direct elections to it. But<br />

when there are direct elections now, the same<br />

effect is produced.” 10<br />

9<br />

G.K. Galbraith, Good Society: A Human Agenda, 1998,<br />

p. 142.<br />

10 Robert W. McChesney, Power and Politics in the United<br />

States of America, 1987, p. 106. Douglas Dowd also<br />

quotes McChesney and says as follows: “Throughout the<br />

capitalist era, whether in the United States or elsewhere,<br />

power has (so to speak) been "bought." <strong>No</strong>t for nothing,<br />

for example, was the U.S. Senate called "the rich man's<br />

club" in the years termed "the gilded age," or "the great<br />

barbecue" when there was no direct election of senators.<br />

But when that changed, means were found to bring about<br />

the same result, with respect to the Senate as with other<br />

areas of government – in keeping with Woodrow Wilson's<br />

remark (made in 1912) that "When the government<br />

becomes important, it becomes important to control the<br />

government".” {Douglas Dowd, Capitalism & Its<br />

Economics: A Critical History, Pluto Press, London,<br />

2000, p. 8}<br />

<strong>No</strong>w, coming back home, India is described as<br />

the largest democracy in the world. But the<br />

Indian Parliament may also be described as a rich<br />

man’s club. In the General Elections of 2014, out<br />

of a total membership of 543, <strong>31</strong>6 of the elected<br />

parliamentarians were billionaires. <strong>11</strong> They too<br />

were elected with a minority vote. Why this<br />

happened? Compared to the first general elections<br />

(1951-52), election expenses had increased by<br />

more than hundred times. <strong>No</strong>w a candidate to the<br />

Parliament [ordinarily] has to spend no less than<br />

Rs. 20 crores. Therefore, only the very rich can<br />

contest in the elections.<br />

Indian Constitution: The way our Constitution<br />

was drafted and approved was itself questionable.<br />

Ten months before independence (<strong>No</strong>vember<br />

1946), when Britain decided to leave, a<br />

Constitution Assembly was elected by the<br />

provincial assemblies, which were themselves<br />

elected by a limited franchise on 10 <strong>March</strong> 1946.<br />

The total members of this Constituent Assembly<br />

were 389, out of which 286 were elected by the<br />

Provincial Assemblies and 93 were nominated by<br />

Princely States. After two years of deliberations a<br />

Constitution was adopted on 26 <strong>No</strong>vember 1949<br />

and came into force on 26 January 1950.<br />

The Preamble of the Constitution declares:<br />

“India is a sovereign, [Socialist, Secular] 12<br />

Democratic Republic,” and adds “We the People<br />

of India give to ourselves this Constitution.” How<br />

286 indirectly elected and 93 nominated members could<br />

call themselves as representatives of the people of India?<br />

This is a mockery of democracy. Further, the<br />

appellation ‘Socialist’ is false because Article <strong>31</strong><br />

recognizes private property and its acquisition as<br />

a fundamental right. How socialism can be<br />

achieved by private property? Perhaps, in order to<br />

pacify the people, the Constitution has included<br />

the Directive Principles of State Policy, some of<br />

which are:<br />

<strong>11</strong> India Election Watch: Report on 2014 General Elections;<br />

the number of billionaires is based on the affidavits filed<br />

by the candidates along with their nomination papers.<br />

12 Added later by the 42 nd Constitution Amendment 1976.<br />

Law Animated World, <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong> 14

(20<strong>15</strong>) 1 LAW A Historical View of Law (V.V. Reddy) <strong>15</strong><br />

1. To secure adequate means of living to all<br />

citizens (Article 32);<br />

2. To prevent concentration of wealth in the<br />

hands of some in order to secure an egalitarian<br />

distribution of income (Article 22);<br />

3. To secure equal pay to equal work (Article 36);<br />

4. <strong>No</strong> child under the age of fourteen be<br />

employed in factories, mines or any other jobs<br />

(Article 39);<br />

5. To introduce free and compulsory primary<br />

education for all children (Article 45).<br />

But unlike fundamental rights, the directive<br />

principles are not justiciable [though they are said<br />

to be fundamental in the governance of the state].<br />

They are only well-meaning promises. However,<br />

to date, none of the Directive Principles has seen<br />

the light of the day. For the Article <strong>31</strong> itself<br />

makes it impossible to implement the Directive<br />

Principles; 13 it makes Article 22 infructuous. As a<br />

13 Article <strong>31</strong> in the Original Constitution as adopted and<br />

come to be enforced in 1949-50 ran as follows:<br />

Right to Property: Compulsory acquisition of Property –<br />

<strong>31</strong>. (1) <strong>No</strong> person shall be deprived of his property save<br />

by authority of law.<br />

(2) <strong>No</strong> property, movable or immovable, including any<br />

interest in, or in any company owning, any commercial<br />

or industrial undertaking, shall be taken possession of or<br />

acquired for public purposes under any law authorising<br />

the taking of such possession or such acquisition, unless<br />

the law provides for compensation for the property taken<br />

possession of or acquired and either fixes the amount of<br />

compensation, or specifies the principles on which, and<br />

the manner in which, the compensation is to be<br />

determined and given.<br />

(3) <strong>No</strong> such law as is referred to in clause (2) made by<br />

the Legislature of a State shall have effect unless such<br />

law, having been reserved for the consideration of the<br />

President, has received his assent.<br />

(4) If any Bill pending at the commencement of this<br />

Constitution in the Legislature of a State has, after it has<br />

been passed by such Legislature, been reserved for the<br />

consideration of the President and has received his<br />

assent, then, notwithstanding anything in this<br />

Constitution, the law so assented to shall not be called in<br />

question in any court on the ground that it contravenes<br />

the provisions of clause (2).<br />

(5) <strong>No</strong>thing in clause (2) shall affect –<br />

(a) the provisions of any existing law other than a law to<br />

which the provisions of clause (6) apply, or<br />

result, during the last 60 years concentration of wealth<br />

has increased manifold. The ten big industrial houses,<br />

led by Ambanis, own nearly one-fifth of the GDP, and<br />

India ranks third in the world, after the USA and<br />

China, in the number of billionaires. At the other<br />

pole, about 40% of Indians live below the poverty line,<br />

which number is not small, amounting to some 460<br />

million or equal to the population of Europe.<br />

A Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices<br />

Act was made in the late 60’s but many a time<br />

thereafter the upper limit of the value of corporate<br />

(b) the provisions of any law which the State may<br />

hereafter make (i) for the purpose of imposing or levying<br />

any tax or penalty, or (ii) for the promotion of public<br />

health or the prevention of danger to life or property, or<br />

(iii) in pursuance of any agreement entered into between<br />

the Government of the Dominion of India or the<br />

Government of India and the Government of any other<br />

country, or otherwise, with respect to property declared<br />

by law to be evacuee property.<br />

(6) Any law of the State enacted not more than eighteen<br />

months before the commencement of this Constitution<br />

may within three months from such commencement be<br />

submitted to the President for his certification; and<br />

thereupon, if the President by public notification so<br />

certifies, it shall not be called in question in any court on<br />

the ground that it contravenes the provision of clause (2)<br />

of this article or has contravened the provisions of subsection<br />

(2) of section 299 of the Government of India<br />

Act, 1935.” However, this Article <strong>31</strong>, which made and<br />

declared the right to property a fundamental right, was<br />

later repealed by the Constitution (Forty-fourth<br />

Amendment) Act, 1978 w.e.f. 20-06-1979 thus taking<br />

out the right to property from the list of fundamental<br />

rights enshrined in Chapter III of the Constitution.<br />

However, the right to property was retained as a<br />

constitutional right by insertion, by the same Amendment<br />

Act, of Article 300A, which runs as follows: “Chapter IV:<br />

Right to Property: 300A. Persons not to be deprived of<br />

property save by authority of law. – <strong>No</strong> person shall be<br />

deprived of his property save by authority of law.” True,<br />

this author’s comments are mainly based on the old<br />

Article <strong>31</strong> which was a part of the fundamental rights<br />

chapter, but even with the repeal of that article and<br />

relegation of right to property to the status of a mere<br />

constitutional right, the protection, promotion and rabid<br />

capitalization and even concentration of private property<br />

is progressing in a nonchalant manner in our country<br />

belying the socialist goal proclaimed in the [amended]<br />

preamble.<br />

<strong>15</strong><br />

Law Animated World, <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong>

16 A Historical View of Law (V.V. Reddy) (20<strong>15</strong>) 1 LAW<br />

assets was raised upwards. There are anticorruption<br />

laws on the statute book, but they are<br />

toothless. As a result, black money is generated<br />

and deposited in Swiss banks, amounting to<br />

thousands of million dollars. Successive<br />

governments promised to bring back the black<br />

money, but in vain. [This shows the power of<br />

black money and how percipient and pertinent is<br />

that] Lord Acton’s remark: “Power corrupts, and<br />

absolute power corrupts absolutely.” 14<br />

Conclusion: Law by its very nature is negative. It<br />

orders people “not to do this or that – else you will be<br />

punished.” Therefore, people obey law out of fear of<br />

being fined or jailed. Still, lawbreakers abound –<br />

from ordinary thieves to big land-grabbers. The<br />

former cannot defend themselves by hiring<br />

lawyers, while the latter can afford going from<br />

the lower to the higher courts. Therefore, years,<br />

sometimes, decades, elapse, before justice is delivered.<br />

So, it is said: “Justice delayed is justice denied.” Then,<br />

what is Justice? It is an abstract word, difficult to<br />

be defined. Further, what was Justice in the past may<br />

become injustice today e.g. slavery. Likewise,<br />

charging interest on loans was considered<br />

immoral by Christianity, but under Capitalism it<br />

is lawful. Similarly, prostitution is still considered<br />

immoral, but it is an existing fact. When a fact is<br />

not recognized by law, it is no more a law. Dowry is<br />

banned by law, but the custom proved stronger. So<br />

there are few instances in India, where dowry is<br />

not given and taken. The same is the case with child<br />

marriages. Well then, what is the use of such law, when<br />

it cannot be enforced?<br />

* * * * *<br />

14 “I cannot accept your canon that we are to judge Pope<br />

and King unlike other men, with a favorable presumption<br />

that they did no wrong. If there is any presumption it is the<br />

other way against holders of power, increasing as the power<br />

increases. Historic responsibility [that is, the later judgment<br />

of historians] has to make up for the want of legal<br />

responsibility [that is, legal consequences during the rulers'<br />

lifetimes]. Power tends to corrupt and absolute power<br />

corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men,<br />

even when they exercise influence and not authority: still more<br />

when you super-add the tendency or the certainty of corruption<br />

by authority.” - Lord Acton (John Emerich Edward Dalberg) in<br />

his Letter to Archbishop Mandell Creighton (Apr. 5, 1887).<br />

PLEASE NOTE<br />

Two precious research based books on some aspects of<br />

freedom struggle in India, published by Marxist Study<br />

Forum, available for sale at 40% discount for individuals.<br />

1. REMEMBERING OUR REVOLUTIONARIES<br />

(Price: Rs. 300/-) by Prof. Satyavrata Ghosh;<br />

Ed: I.M. <strong>Sharma</strong><br />

2. EASTER REBELLION IN INDIA:<br />

THE CHITTAGONG UPRISING<br />

by I. <strong>Mallikarjuna</strong> <strong>Sharma</strong>, Price: Rs. 360/-.<br />

“Recognized even by the British adversaries as ‘an amazing<br />

and daring coup’ which brought an ‘electric effect’ and<br />

‘changed the entire outlook of the Bengal revolutionaries’,<br />

the Chittagong Uprising played a glorious role and occupies<br />

an important place in the history of the Indian Freedom<br />

Struggle. In addition to giving rise to an unprecedented surge<br />

of revolutionary action by the Bengali youth, it also inspired<br />

lakhs of people all over India and gave a great fillip to the<br />

national movement. The historic role of the armed<br />

revolutionaries in our struggle for independence is generally<br />

overlooked or cast aside with mere lip service. The same fate<br />

generally befell the Chittagong revolutionaries too.<br />

This book as if atones for the general wrong done to these<br />

heroic rebels. It contains several precious and informative<br />

articles about the Irish Easter Rebellion and its inspiration to<br />

the Indian revolutionaries, and about the daring deeds and<br />

glowing sacrifices of the Chittagong revolutionaries led by<br />

Masterda Surya Sen…<br />

A book not to be missed by serious students of history or<br />

devoted patriots of the motherland…”<br />

MO/Cheques/DDs to be sent in favour of:<br />

I. MALLIKARJUNA SHARMA,<br />

H. <strong>No</strong>. 6-3-243/<strong>15</strong>6, M.S. Makta, Opp. Raj Bhavan,<br />

HYDERABAD - 500 082 (A.P.)<br />

(Please add Rs. 75/- service charges)<br />

Law Animated World, <strong>15</strong>-<strong>31</strong> <strong>March</strong> 20<strong>15</strong> 16

THE ZIETGEIST MOVEMENT : A NEW TRAIN OF THOUGHT ♣<br />

PART III: A NEW TRAIN OF THOUGHT<br />

<strong>15</strong>. THE INDUSTRIAL GOVERNMENT-<br />

Modern politics is business politics...This is true both of<br />

foreign and domestic policy. Legislation, police surveillance,<br />

the administration of justice, the military and diplomatic<br />

service, all are chiefly concerned with business relations,<br />

pecuniary interests, and they have little more than an<br />

incidental bearing on other human interests. 789<br />

-Thorstein Veblen<br />

Political v. Technical Governance<br />

The nature and unfolding of the politically<br />

driven model of representative democracy,<br />

legislation creation and the sanctioned<br />

enforcement of law, are all borne out of natural<br />

tendencies inherent to the act of commerce and<br />

trade, operating within a scarcity-driven social<br />

order.<br />

The development of this commercial<br />

regulation and the rationale behind the very<br />

existence of “state governance” is quite easy to<br />

trace historically. After the Neolithic revolution,<br />

humanity's once nomadic patterns shifted toward<br />

a new propensity to farm, settle and create towns.<br />

Specialization flourished and trade was hence<br />

inevitable. However, given the possibility for<br />

imbalance and dispute, as regional populations<br />

grew and regional resources often became more<br />

scarce, a security and regulatory practice<br />

manifested to protect a community's land,<br />

property, trade integrity and the like.<br />

The use of an “army”, which is sanctioned to<br />

protect by public decree, became standardized,<br />

along with an adjacent legal or regulatory<br />

authority complex, sanctioned to essentially give<br />

power to a set group of officials which facilitate<br />

such policy creation, enforcement, trials,<br />

punishment practices and the like.<br />

♣ Courtesy: http://www.thezeitgeistmovement.com/; slightly<br />

edited; continued from Law Animated World,<br />

28 February 20<strong>15</strong> issue; emphases in bold ours - IMS.<br />

789 The Theory of Business Enterprise, Thorstein Veblen,<br />

p. 269.<br />

This is mentioned here as there are many<br />

schools of economic thought in the early 21 st century<br />

that talk about reducing or even removing the state<br />

apparatus entirely, falsely assuming the state itself is a<br />

separate entity and the starting point of blame for current<br />

societal woes or economic inefficiencies. Yet, on the<br />

other side of the debate spectrum is a general cry<br />

for increased state regulation of the market to<br />

ensure more limits on business manipulation and<br />

hence work to avoid what has been often<br />

perceived as “crony capitalism”. 790 The truth of<br />

the matter is that this polarizing, false duality<br />

between the “state” and the “market” is blind to<br />

the true root cause of what is actually causing<br />

problems, not realizing that the dyad of state and<br />