Museum of Modern Literature Marbach, Germany David Chipperfield

Museum of Modern Literature Marbach, Germany David Chipperfield

Museum of Modern Literature Marbach, Germany David Chipperfield

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

14<br />

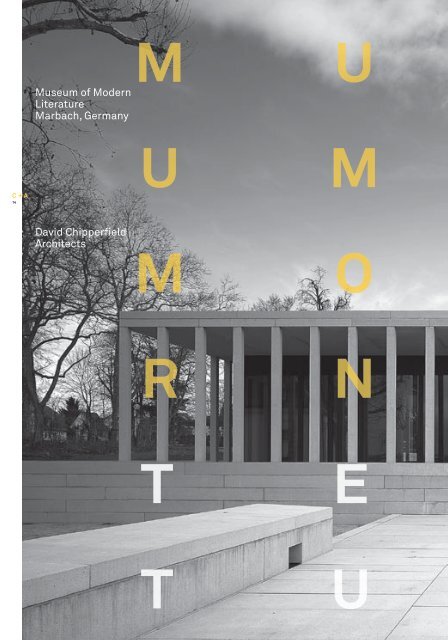

<strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Modern</strong><br />

<strong>Literature</strong><br />

<strong>Marbach</strong>, <strong>Germany</strong><br />

<strong>David</strong> <strong>Chipperfield</strong><br />

Architects

<strong>David</strong> <strong>Chipperfield</strong>’s haunting <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Literature</strong><br />

in <strong>Marbach</strong> am Neckar, near Stuttgart, southern <strong>Germany</strong>,<br />

is extraordinary for its reduction <strong>of</strong> architecture to the<br />

barest essentials.<br />

The museum houses and displays books, manuscripts and<br />

artefacts from the extensive 20th century collection in the<br />

Archive for German <strong>Literature</strong> – including the original<br />

manuscripts <strong>of</strong> Franz Kafka’s ‘The Trial’ and Alfred Doblin’s<br />

‘Berlin Alexanderplatz’ – and sits in parkland, embedded<br />

into a ridge overlooking the pretty valley <strong>of</strong> the Neckar River.<br />

It stands like a modern Parthenon on its own small Acropolis,<br />

stripped-to-the-bone-elegant, in stark relationship to the<br />

National Schiller <strong>Museum</strong>, a near-Baroque pile from 1903,<br />

and a contorted brutalist affair from 1973, <strong>of</strong> which it forms<br />

a part. As with nearly all <strong>of</strong> <strong>Chipperfield</strong>’s architecture, this<br />

work is an exercise in rigorous restraint: a classically-inspired,<br />

minimalist temple <strong>of</strong> glass and slender concrete columns<br />

atop a concrete plinth.<br />

But what is more interesting, perhaps, is that <strong>Chipperfield</strong><br />

won the commission for the museum at all. That in a country<br />

still plagued by memories <strong>of</strong> Nazi monumental classicism –<br />

Hitler’s neo-Grecian House <strong>of</strong> German Culture, with its massive<br />

stone columns, is not far away in Munich – and its ongoing<br />

dilemma <strong>of</strong> how to achieve a suitable expression <strong>of</strong><br />

monumentality in its architecture, an architect, a foreign<br />

one at that, would dare propose a neo-classical colonnaded<br />

structure for a building <strong>of</strong> such national importance.<br />

And won in open-competition, to boot!<br />

Maybe it had to fall to an auslander, a foreigner, to convince<br />

the jury that at this distance from the Second World War<br />

an abstracted reduction <strong>of</strong> Nazi classicism might be okay to<br />

contemplate. After all, a few other foreigners – James Stirling<br />

with his Neue Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart <strong>of</strong> 1984 and Norman<br />

Foster and his renovation for the Reichstag in Berlin <strong>of</strong> 1999,<br />

among them – had stamped their own peculiar imprimatur<br />

on <strong>Germany</strong>’s post-war reconstruction.<br />

Challenging an unwritten rule that post-war German buildings<br />

should never have columns, <strong>Chipperfield</strong> nevertheless<br />

entered the competition with his spare, rectilinear temple.<br />

“We felt we were bringing back a sort <strong>of</strong> classicism that hadn’t<br />

been seen in this part <strong>of</strong> <strong>Germany</strong> since the war,” he says.<br />

“And the period was far enough away that the discussion<br />

could be interesting. Germans are willing to analyze what<br />

things mean. It’s a great climate to work in. I wanted to reduce<br />

the architecture to its most simplified, almost primitive form”.<br />

Still, mischievously, he had to reassure one concerned juror<br />

that the slender pre-cast concrete columns weren’t fascist<br />

columns at all but mullions!<br />

Given the parkland site, <strong>Chipperfield</strong> came up with a scheme<br />

for a temple on a podium, where the base, containing six<br />

exhibition galleries, would be partially embedded into the<br />

side <strong>of</strong> the hill, with entry provided via a glass and concrete<br />

colonnaded pavilion on top.<br />

Visitors enter the museum through this upper level lantern,<br />

reminiscent <strong>of</strong> Mies van der Rohe’s entrance to the Berlin Art<br />

Gallery, with its crystalline glass and steel pavilion atop a base.<br />

<strong>Marbach</strong> is sparer, the pavilion marked by a screen <strong>of</strong> skinny<br />

concrete columns, without capitals or bases, wrapped around<br />

its four regular, symmetrical sides.<br />

It sits ever so lightly, transparent-like, over the exhibition<br />

galleries where the columns more frequently turn into<br />

mullions for glass walls or pilasters set against solid panels.<br />

Ro<strong>of</strong> terraces, podium walls and parapets are formed <strong>of</strong><br />

stringently linear planks <strong>of</strong> sandblasted pre-cast concrete<br />

with a limestone aggregate.

issue 09 National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Literature</strong>

Mindful <strong>of</strong> concerns about the columns and overt classical<br />

symmetry <strong>of</strong> the scheme, <strong>Chipperfield</strong> and his project architect,<br />

Alexander Schwartz, pared the columns until they became almost<br />

impossibly thin, mere matchsticks, but still capable <strong>of</strong> being<br />

pre-cast in concrete. They also played a subtle game <strong>of</strong> sorts with<br />

the march <strong>of</strong> the columns: while on the upper lantern all elevations<br />

share a single column where that turns a corner, on the lower<br />

level the colonnades each stop a column-width short <strong>of</strong> the<br />

sharp edge <strong>of</strong> the corner itself. Columns are also omitted where<br />

they signal entrances. The greater challenge though, you suspect,<br />

lay within the museum itself, where the books and manuscripts<br />

were required to be housed in dimly lit (50 lux) spaces to<br />

protect them from daylight. In order not to create a gloomy<br />

or claustrophobic environment, <strong>Chipperfield</strong> tried to expand<br />

the sense <strong>of</strong> enclosure with extra layers <strong>of</strong> outdoor terraces that<br />

take advantage <strong>of</strong> the views across the landscape. “We wanted<br />

these galleries to be dark in a positive way, not just dark boxes,<br />

but rooms with architectural integrity,” he says.<br />

Entering the museum, visitors find themselves in a large hall<br />

where Ipe, a dark Brazilian wood, clads much <strong>of</strong> the walls. Daylight<br />

bathes the limestone floors and in-situ concrete walls and s<strong>of</strong>fits<br />

in an ethereal glow. <strong>Museum</strong> goers then work their way down a<br />

series <strong>of</strong> grand stairs in a carefully choreographed journey <strong>of</strong> axial<br />

turns and views to prepare them for the dimly lit lower ground<br />

galleries, subtly reducing light levels as they descend.<br />

Once on the lowest level, a suite <strong>of</strong> exhibition spaces is arranged<br />

around three anterooms. Rigidly contained in plan, space is<br />

permitted to shift beneath the external terraces that rise and<br />

fall. So, while unified by the consistent palette <strong>of</strong> in-situ concrete<br />

s<strong>of</strong>fits, warm timber walls and limestone floors, each space is<br />

made unique through subtle shifts in ceiling height.<br />

Since the main exhibition galleries, for permanent collections<br />

and temporary exhibitions, were required to have close-control<br />

environments, and as such starved <strong>of</strong> natural light, <strong>Chipperfield</strong><br />

designed these windowless rooms to adjoin a space that<br />

is either a glazed loggia or illuminated by skylights to diminish<br />

the sense <strong>of</strong> having descended into a tomb. The most spectacular<br />

is the smallest room, a temporary exhibition hall, top-lit from<br />

a soaring 11 metre high lantern.<br />

At <strong>Marbach</strong> the language is modest, classical references are<br />

refined to absolute minimum, the architecture one <strong>of</strong> exquisite<br />

lightness. The <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Literature</strong> was awarded the<br />

2007 RIBA Stirling Prize. JR

A spare pavilion marked<br />

by a screen <strong>of</strong> skinny concrete<br />

columns, without capitals or<br />

bases, wrapped around its four<br />

symmetrical sides<br />

issue 09 National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Literature</strong>

issue 09 National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Literature</strong>

An exercise in rigorous restraint;<br />

a classically inspired, minimalist temple<br />

<strong>of</strong> glass and slender concrete columns<br />

atop a concrete plinth<br />

West elevation<br />

Project Statement<br />

The museum is located in <strong>Marbach</strong>’s scenic park, on top<br />

<strong>of</strong> a rock plateau overlooking the valley <strong>of</strong> the Neckar River.<br />

As the birthplace <strong>of</strong> the dramatist Friedrich Schiller, the town’s<br />

park already held the National Schiller <strong>Museum</strong>, built in<br />

1903, and the Archive for German <strong>Literature</strong>, built in the 1970s.<br />

Displaying artefacts from the extensive 20th century collection<br />

from the Archive for German <strong>Literature</strong>, notably the original<br />

manuscripts <strong>of</strong> Franz Kafka’s “The Trial” and Alfred Döblin’s<br />

“Berlin Alexanderplatz”, the museum also provides panoramic<br />

views across and over the distant landscape.<br />

Embedded in the topography, the museum reveals different<br />

elevations depending on the viewpoint. By utilising the steep<br />

slope <strong>of</strong> the site, terraces allow for the creation <strong>of</strong> very different<br />

characters: an intimate, shaded entrance on the brow <strong>of</strong> the<br />

hill facing the National Schiller <strong>Museum</strong> with its forecourt and<br />

park, and a grander, more open series <strong>of</strong> tiered spaces facing<br />

the valley below. A pavilion-like volume is located on the highest<br />

terrace, providing the entrance to the museum. The interiors<br />

<strong>of</strong> the museum reveal themselves as one descends down through<br />

the loggia, foyer and staircase spaces, preparing the visitor for<br />

the dark timber-panelled exhibition galleries, illuminated only<br />

by artificial light due to fragility and sensitivity <strong>of</strong> the works<br />

on display. At the same time, each <strong>of</strong> these environmentally<br />

controlled spaces borders onto a naturally lit gallery, balancing<br />

views inward to the composed, internalized world <strong>of</strong> texts<br />

and manuscripts with the green and scenic valley on the other<br />

side <strong>of</strong> the glass.<br />

A clearly defined material concept using solid materials (fair-<br />

faced concrete, sandblasted reconstituted stone with limestone<br />

aggregate, limestone, wood, felt and glass) gives the calm,<br />

rational architectural language a sensual physical presence.<br />

<strong>David</strong> <strong>Chipperfield</strong> Architects<br />

Longitudinal section<br />

1 5 10 20<br />

1 5 10 20

04<br />

08 06<br />

09<br />

01<br />

07 06<br />

08<br />

11<br />

09<br />

03<br />

02<br />

06<br />

05<br />

06<br />

issue 09 National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Literature</strong><br />

04<br />

04 04<br />

06<br />

08<br />

10<br />

10<br />

ground floor plan<br />

lower ground floor plan<br />

01 foyer/entrance area<br />

02 auditorium<br />

03 double-height lightwell<br />

04 terraces<br />

05 hall<br />

06 exhibition spaces<br />

07 temporary exhibition<br />

08 loggias<br />

09 wc<br />

10 technical rooms<br />

11 archive link

issue 09 National <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Literature</strong>

The columns are impossibly thin,<br />

mere matchsticks, but still capable<br />

<strong>of</strong> being pre-cast in concrete

issue 09 <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Literature</strong><br />

Project <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Modern</strong> <strong>Literature</strong><br />

Location <strong>Marbach</strong> am Neckar, <strong>Germany</strong><br />

Architect <strong>David</strong> <strong>Chipperfield</strong> Architects,<br />

Design/Project Architect Alexander Schwartz<br />

Project team Harald Muller, Martina Betzold,<br />

Andrea Hartmann, Christian Helfrich, Franziska Rusch,<br />

Tobias Stiller, Vincent Taupitz, Mirjam von Busch,<br />

Laura Fogarasi, Barbara Koller, Hannah Jonas<br />

Site supervision Wenzel + Wenzel<br />

Project manager Drees + Sommer<br />

Structural engineer Ingenieurgruppe Bauen,<br />

Services engineer Jaeger, Mornhinweg + Partner<br />

Ingenieurgesellschaft, Stuttgart;<br />

Ibb Burrer + Deuring Ingenieurburo Gmbh, Ludwigsburg<br />

Photographer Christian Richters<br />

27