Menopausal hormones and risk of ovarian cancer - ResearchGate

Menopausal hormones and risk of ovarian cancer - ResearchGate

Menopausal hormones and risk of ovarian cancer - ResearchGate

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

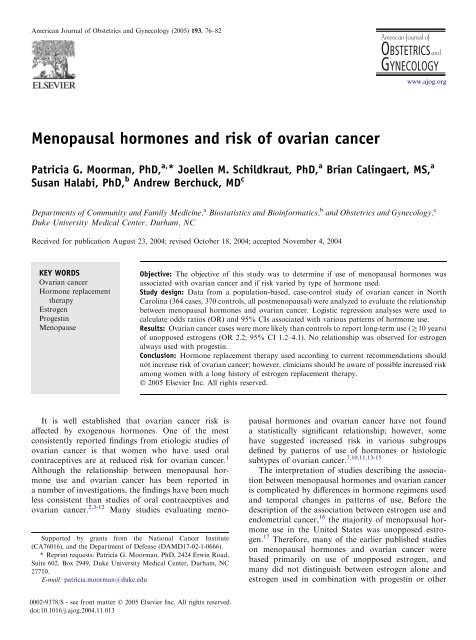

American Journal <strong>of</strong> Obstetrics <strong>and</strong> Gynecology (2005) 193, 76–82<br />

www.ajog.org<br />

<strong>Menopausal</strong> <strong>hormones</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>risk</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong><br />

Patricia G. Moorman, PhD, a, * Joellen M. Schildkraut, PhD, a Brian Calingaert, MS, a<br />

Susan Halabi, PhD, b Andrew Berchuck, MD c<br />

Departments <strong>of</strong> Community <strong>and</strong> Family Medicine, a Biostatistics <strong>and</strong> Bioinformatics, b <strong>and</strong> Obstetrics <strong>and</strong> Gynecology, c<br />

Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC<br />

Received for publication August 23, 2004; revised October 18, 2004; accepted November 4, 2004<br />

KEY WORDS<br />

Ovarian <strong>cancer</strong><br />

Hormone replacement<br />

therapy<br />

Estrogen<br />

Progestin<br />

Menopause<br />

Objective: The objective <strong>of</strong> this study was to determine if use <strong>of</strong> menopausal <strong>hormones</strong> was<br />

associated with <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> <strong>and</strong> if <strong>risk</strong> varied by type <strong>of</strong> hormone used.<br />

Study design: Data from a population-based, case-control study <strong>of</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> in North<br />

Carolina (364 cases, 370 controls, all postmenopausal) were analyzed to evaluate the relationship<br />

between menopausal <strong>hormones</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>. Logistic regression analyses were used to<br />

calculate odds ratios (OR) <strong>and</strong> 95% CIs associated with various patterns <strong>of</strong> hormone use.<br />

Results: Ovarian <strong>cancer</strong> cases were more likely than controls to report long-term use (R10 years)<br />

<strong>of</strong> unopposed estrogens (OR 2.2; 95% CI 1.2–4.1). No relationship was observed for estrogen<br />

always used with progestin.<br />

Conclusion: Hormone replacement therapy used according to current recommendations should<br />

not increase <strong>risk</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>; however, clinicians should be aware <strong>of</strong> possible increased <strong>risk</strong><br />

among women with a long history <strong>of</strong> estrogen replacement therapy.<br />

Ó 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.<br />

Supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute<br />

(CA76016), <strong>and</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> Defense (DAMD17-02-1-0666).<br />

* Reprint requests: Patricia G. Moorman, PhD, 2424 Erwin Road,<br />

Suite 602, Box 2949, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC<br />

27710.<br />

E-mail: patricia.moorman@duke.edu<br />

It is well established that <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> <strong>risk</strong> is<br />

affected by exogenous <strong>hormones</strong>. One <strong>of</strong> the most<br />

consistently reported findings from etiologic studies <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> is that women who have used oral<br />

contraceptives are at reduced <strong>risk</strong> for <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>. 1<br />

Although the relationship between menopausal hormone<br />

use <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> has been reported in<br />

a number <strong>of</strong> investigations, the findings have been much<br />

less consistent than studies <strong>of</strong> oral contraceptives <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>. 2,3-12 Many studies evaluating menopausal<br />

<strong>hormones</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> have not found<br />

a statistically significant relationship; however, some<br />

have suggested increased <strong>risk</strong> in various subgroups<br />

defined by patterns <strong>of</strong> use <strong>of</strong> <strong>hormones</strong> or histologic<br />

subtypes <strong>of</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>. 7,10,11,13-15<br />

The interpretation <strong>of</strong> studies describing the association<br />

between menopausal <strong>hormones</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong><br />

is complicated by differences in hormone regimens used<br />

<strong>and</strong> temporal changes in patterns <strong>of</strong> use. Before the<br />

description <strong>of</strong> the association between estrogen use <strong>and</strong><br />

endometrial <strong>cancer</strong>, 16 the majority <strong>of</strong> menopausal hormone<br />

use in the United States was unopposed estrogen.<br />

17 Therefore, many <strong>of</strong> the earlier published studies<br />

on menopausal <strong>hormones</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> were<br />

based primarily on use <strong>of</strong> unopposed estrogen, <strong>and</strong><br />

many did not distinguish between estrogen alone <strong>and</strong><br />

estrogen used in combination with progestin or other<br />

0002-9378/$ - see front matter Ó 2005 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.<br />

doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.013

Moorman et al 77<br />

<strong>hormones</strong>. Since the late 1970s, physicians have tended<br />

to prescribe lower dose estrogens, <strong>and</strong> a much larger<br />

proportion <strong>of</strong> women have used menopausal <strong>hormones</strong><br />

consisting <strong>of</strong> both an estrogen <strong>and</strong> progestin. 17,18 Given<br />

that the effects <strong>of</strong> progestins on the ovaries may be very<br />

different from that <strong>of</strong> estrogens, with some investigators<br />

hypothesizing a protective effect <strong>of</strong> progestins, 19,20 the use<br />

<strong>of</strong> combination therapy could have very different effects<br />

on <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> <strong>risk</strong> than estrogen alone. However,<br />

relatively few studies have assessed the association<br />

between different hormone regimens <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>.<br />

In addition to the possibility that the effect <strong>of</strong><br />

menopausal <strong>hormones</strong> depends on the specific regimen<br />

used, some studies have suggested that the <strong>risk</strong> may vary<br />

between histologic subtypes <strong>of</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>. Several<br />

studies have reported larger increases in <strong>risk</strong>s for serous<br />

<strong>and</strong>/or endometrioid than for other subtypes. 13-15<br />

In this report we describe the associations between<br />

menopausal hormone use <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> using data<br />

from a population-based, case-control study <strong>of</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong><br />

<strong>cancer</strong> conducted in North Carolina between 1999 <strong>and</strong><br />

2003. The analyses focus on the effects <strong>of</strong> different<br />

hormone regimens on epithelial <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> overall,<br />

<strong>and</strong> on different histologic subtypes <strong>of</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>.<br />

Material <strong>and</strong> methods<br />

We analyzed data from Phase I <strong>of</strong> the North Carolina<br />

Ovarian Cancer Study, a population-based case-control<br />

study <strong>of</strong> newly diagnosed epithelial <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> cases<br />

in a 48-county area <strong>of</strong> North Carolina. Cases were<br />

identified using a rapid case ascertainment system<br />

developed by the North Carolina Central Cancer<br />

Registry, a statewide population-based tumor registry.<br />

Pathology reports for all <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>s diagnosed in<br />

the hospitals in the study area were forwarded to the<br />

Central Cancer Registry, <strong>and</strong> then to the study <strong>of</strong>fice<br />

within 2 months <strong>of</strong> diagnosis. Of the 53 hospitals in the<br />

study area that treat <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> patients, 52 agreed<br />

to participate in the study. Eligible cases were women<br />

aged 20 to 74 years who were diagnosed with primary<br />

epithelial <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> between January 1, 1999 <strong>and</strong><br />

March 31, 2003, <strong>and</strong> resided in the 48-county study area.<br />

Both invasive tumors <strong>and</strong> those with low malignant<br />

potential (borderline tumors) were included. Permission<br />

to contact the <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> cases was requested from<br />

the physician <strong>of</strong> record on the pathology report. All<br />

participants were English-speaking, mentally competent<br />

to complete an interview, <strong>and</strong> able to give informed<br />

consent. All cases underwent st<strong>and</strong>ardized pathologic<br />

<strong>and</strong> histologic review to confirm the diagnosis. Of 883<br />

cases <strong>of</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> identified through the hospitals,<br />

784 were eligible for the study. Reasons for ineligibility<br />

included diagnosis other than epithelial <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong><br />

(n = 55), date <strong>of</strong> diagnosis before initiation <strong>of</strong> study<br />

(n = 11), inability to complete an interview in English<br />

due to language or cognitive issues (n = 16), age greater<br />

than 74 years (n = 12), residence outside <strong>of</strong> the study<br />

area (n = 4), <strong>and</strong> institutionalized patient (n = 1). The<br />

overall response rate among eligible cases was 76%,<br />

although 86% <strong>of</strong> women who were contacted were<br />

successfully recruited into the study. Reasons that cases<br />

were not interviewed included death (4%), debilitating<br />

illness (2%), patient refusal (7%), physician refusal<br />

(3%), <strong>and</strong> inability to locate the woman (8%). A total<br />

<strong>of</strong> 594 cases were enrolled in the study.<br />

Controls were identified from the same 48-county<br />

area that generated the cases using r<strong>and</strong>om digit dialing<br />

methodology. Controls were frequency matched to cases<br />

by race <strong>and</strong> age (within 5 years). Race was based on selfreport<br />

by the participant. Health Care Financing <strong>and</strong><br />

Administration tapes were initially used to identify<br />

controls aged 65 to 74 years; however, this strategy<br />

was ab<strong>and</strong>oned due to the difficulty in contacting<br />

potential controls because <strong>of</strong> the absence <strong>of</strong> telephone<br />

numbers on these tapes. Eligible controls resided in the<br />

same 48-county area as the cases, had no history <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>cancer</strong>, <strong>and</strong> had to have at least 1 ovary intact. As was<br />

required for the cases, controls had to be Englishspeaking,<br />

mentally competent to complete an interview,<br />

<strong>and</strong> able to give informed consent. Seventy-one percent<br />

<strong>of</strong> controls (n = 628) identified by r<strong>and</strong>om digit dialing<br />

who met the eligibility criteria were successfully enrolled<br />

into the study. The study protocol was approved by<br />

institutional review boards at Duke University Medical<br />

Center <strong>and</strong> all hospitals that participated in the study.<br />

The analyses presented here are restricted to postmenopausal<br />

cases (n = 364) <strong>and</strong> controls (n = 370). We<br />

included: (1) women who reported their menstrual<br />

periods had stopped naturally; (2) women who reported<br />

they began hormone replacement therapy before their<br />

periods stopped completely; (3) women who had a hysterectomy<br />

without bilateral oophorectomy <strong>and</strong> were at<br />

least 51 years <strong>of</strong> age; <strong>and</strong> (4) women whose periods<br />

stopped due to chemotherapy unrelated to <strong>ovarian</strong><br />

<strong>cancer</strong>. To be eligible for the study, controls were<br />

required to have at least 1 ovary; therefore, none were<br />

postmenopausal due to bilateral oophorectomy. Four <strong>of</strong><br />

the cases were postmenopausal due to bilateral oophorectomy<br />

(but still were subsequently diagnosed with<br />

<strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>).<br />

Cases <strong>and</strong> controls were interviewed in person by<br />

trained nurse interviewers in the home <strong>of</strong> the study<br />

participant or at another convenient location. A 90-<br />

minute questionnaire was administered to obtain information<br />

on known <strong>and</strong> suspected <strong>risk</strong> factors for<br />

<strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>, including family history <strong>of</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> in first<strong>and</strong><br />

second-degree relatives, menstrual characteristics,<br />

pregnancy <strong>and</strong> breastfeeding history, hormone use, <strong>and</strong><br />

lifestyle factors such as smoking history, alcohol consumption,<br />

physical activity, <strong>and</strong> occupational history.

78 Moorman et al<br />

A life-event calendar on which major events in the<br />

woman’s life, such as pregnancies <strong>and</strong> marriages, were<br />

recorded was used to aid recall. Body mass index (BMI)<br />

was calculated based on measured height <strong>and</strong> selfreported<br />

weight from 1 year ago (kg/m 2 ). BMI from 1<br />

year ago was used because many cases reported recent<br />

weight changes related to the <strong>cancer</strong> or its treatment.<br />

In regard to hormone use, women were asked if they<br />

had used PremarinÒ or conjugated estrogens, other estrogen<br />

pills, or estrogen patches. If they responded affirmatively<br />

to use <strong>of</strong> any <strong>of</strong> these types <strong>of</strong> estrogen, they were<br />

asked if they had used progestin along with the estrogen.<br />

The women also were asked about use <strong>of</strong> progestin alone,<br />

testosterone, or any other hormone pills. For each<br />

hormone used, we obtained the name <strong>of</strong> the hormone,<br />

ages at first <strong>and</strong> last use, total duration <strong>of</strong> use, <strong>and</strong> dosing<br />

regimen (every day, R21 days/month, or !21 days/<br />

month). We examined the type <strong>of</strong> hormone used (estrogen<br />

only; progestin only; estrogen always taken with progestin;<br />

estrogen taken sometimes with progestin, sometimes<br />

alone; testosterone with estrogen <strong>and</strong>/or<br />

progestin), the total duration <strong>of</strong> use, <strong>and</strong> the time since<br />

last use.<br />

Statistical analyses<br />

Cases <strong>and</strong> controls were compared in regard to demographic<br />

characteristics <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> <strong>risk</strong> factors<br />

using t tests for continuous variables <strong>and</strong> chi-square<br />

tests for categorical variables. Unconditional logistic<br />

regression analyses were used to calculate odds ratios<br />

(ORs) <strong>and</strong> 95% CIs for the association between<br />

hormone use <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>, taking into account<br />

potential confounders. Variables considered as potential<br />

confounders in the multivariable models included age<br />

(continuous), race (black/non-black), parity (continuous),<br />

tubal ligation (yes/no), oral contraceptive use (yes/<br />

no), history <strong>of</strong> breastfeeding (yes/no), hysterectomy<br />

(yes/no), history <strong>of</strong> breast or <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> in a firstdegree<br />

relative (yes/no), BMI 1 year before interview<br />

(continuous), <strong>and</strong> educational level (less than high<br />

school, high school graduate, or greater than high<br />

school). To test for trend across categories <strong>of</strong> duration,<br />

we created an ordinal variable by assigning nonusers<br />

a value <strong>of</strong> 0, users in the shortest duration category<br />

a value <strong>of</strong> 1, the next highest duration category a value<br />

<strong>of</strong> 2, etc. We then included this ordinal term in our<br />

logistic regression model, <strong>and</strong> took the P value corresponding<br />

to this variable as our test <strong>of</strong> trend. All<br />

analyses were performed using SAS 8.0 (SAS Institute,<br />

Inc, Cary, NC).<br />

Results<br />

Table I presents selected characteristics <strong>of</strong> the cases <strong>and</strong><br />

controls. Although not all differences were statistically<br />

Table I Selected characteristics <strong>of</strong> cases <strong>and</strong> controls, the<br />

North Carolina Ovarian Cancer Study<br />

Cases<br />

(n = 364)<br />

Controls<br />

(n = 370)<br />

n (%) n (%) P value*<br />

Age (y)<br />

!40 0 (0) 1 (0) .006<br />

40-49 12 (3) 8 (2)<br />

50-59 145 (40) 116 (31)<br />

60-69 148 (41) 158 (43)<br />

O70 59 (16) 87 (24)<br />

Race<br />

White 312 (86) 308 (83) .56<br />

African American 47 (13) 54 (15)<br />

Other 5 (1) 8 (2)<br />

Type <strong>of</strong> menopause<br />

Natural 191 (52) 194 (52) .40<br />

Began <strong>hormones</strong> before 51 (14) 65 (18)<br />

periods stopped<br />

Surgical 119 (33) 110 (30)<br />

Chemotherapy 3 (1) 1 (0)<br />

Months <strong>of</strong> pregnancy<br />

None 47 (13) 30 (8) .006<br />

!9 13 (4) 8 (2)<br />

9-18 125 (34) 135 (36)<br />

19-36 140 (39) 141 (38)<br />

O36 38 (10) 56 (15)<br />

Missing 1 0<br />

Months <strong>of</strong> breastfeeding<br />

None 260 (72) 247 (67) .68<br />

!6 37 (10) 48 (13)<br />

6-12 36 (10) 35 (9)<br />

O12 29 (8) 39 (11)<br />

Missing 2 1<br />

Oral contraceptive use (m)<br />

None 158 (43) 175 (47) .22<br />

!12 38 (10) 30 (8)<br />

12-36 62 (17) 66 (18)<br />

O36 96 (26) 92 (25)<br />

Unknown duration <strong>of</strong> use 10 (3) 7 (2)<br />

Tubal ligation<br />

No 281 (77) 259 (70) .027<br />

Yes 83 (23) 111 (30)<br />

1st degree family history <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong><br />

No 344 (95) 357 (96) .18<br />

Yes 19 (5) 12 (3)<br />

Missing 1 1<br />

Body mass index (kg/m 2 )<br />

Quartile 1 82 (23) 90 (25) .16<br />

Quartile 2 94 (26) 91 (25)<br />

Quartile 3 75 (21) 90 (25)<br />

Quartile 4 104 (29) 91 (25)<br />

Missing 9 8<br />

Education<br />

!High school 36 (10) 62 (17) .062<br />

High school graduate 122 (34) 99 (27)<br />

OHigh school 206 (57) 209 (56)<br />

* P values based on t tests for continuous variables (age, months<br />

<strong>of</strong> pregnancy, months <strong>of</strong> breastfeeding, months <strong>of</strong> oral contraceptive<br />

use, body mass index) <strong>and</strong> chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Moorman et al 79<br />

Table II Odds ratios for <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> associated with hormone use<br />

Cases<br />

(n = 364)<br />

Controls<br />

(n = 370)<br />

n n OR* 95% CI OR y 95% CI<br />

Never users 129 152 1.0 (Reference) 1.0 (Reference)<br />

Ever user 235 218 1.2 (0.9-1.6) 1.2 (0.8-1.6)<br />

Duration <strong>of</strong> use<br />

!12 months 11 14 0.8 (0.4-1.9) 0.8 (0.3-1.9)<br />

12-59 months 68 64 1.1 (0.7-1.6) 1.2 (0.7-1.9)<br />

60-119 months 42 42 1.0 (0.6-1.7) 1.0 (0.6-1.6)<br />

O119 months 96 78 1.5 (1.0-2.2) 1.5 (1.0-2.3)<br />

Missing 18 20<br />

Time since last use<br />

!12 months 147 145 1.1 (0.8-1.5) 1.1 (0.7-1.5)<br />

12-59 months 41 31 1.4 (0.8-2.4) 1.6 (0.9-2.8)<br />

60-119 months 15 7 2.4 (0.9-6.1) 2.6 (1.0-7.0)<br />

O119 months 11 12 1.1 (0.5-2.7) 1.2 (0.5-2.8)<br />

Missing 21 23<br />

* ORs (odds ratios) adjusted for age <strong>and</strong> race using logistic regression modeling.<br />

y ORs adjusted for age, race, parity, tubal ligation, hysterectomy, BMI 1 year before interview, 1st degree family history <strong>of</strong> breast or <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>,<br />

breastfeeding (yes/no), oral contraceptive use (yes/no), <strong>and</strong> educational level using logistic regression modeling.<br />

Table III Odds ratios for <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> by hormone regimen used <strong>and</strong> duration <strong>of</strong> use<br />

Cases<br />

(n = 364)<br />

Controls<br />

(n = 370)<br />

n n OR* 95% CI OR y 95% CI<br />

Never use 129 152 Referent Referent<br />

Estrogen only<br />

Ever use 105 79 1.2 (0.7-2.0) 1.5 (0.9-2.3)<br />

!12 months 5 6 0.8 (0.2-2.9) 0.9 (0.3-3.2)<br />

12-59 months 23 24 1.0 (0.5-1.8) 1.2 (0.6-2.3)<br />

60-119 months 17 11 1.7 (0.7-3.7) 1.5 (0.6-3.5)<br />

O119 months 52 32 2.1 (1.2-3.4) 2.2 (1.2-4.1)<br />

Missing duration 8 6<br />

Estrogen always with progestin<br />

Ever use 70 87 0.8 (0.6-1.3) 0.9 (0.6-1.4)<br />

!12 months 3 7 0.5 (0.1-1.8) 0.5 (0.1-2.0)<br />

12-59 months 29 31 0.9 (0.5-1.7) 1.0 (0.6-1.9)<br />

60-119 months 14 14 1.0 (0.4-2.2) 1.1 (0.5-2.6)<br />

O119 months 20 28 0.9 (0.5-1.7) 1.0 (0.5-2.0)<br />

Missing duration 4 7<br />

Estrogen <strong>and</strong> progestin, not always<br />

used together<br />

Ever use 44 38 1.2 (0.7-2.0) 1.3 (0.8-2.2)<br />

!12 months 0 1 - -<br />

12-59 months 9 4 1.8 (0.5-6.3) 2.2 (0.6-7.9)<br />

60-119 months 10 14 0.7 (0.3-1.6) 0.7 (0.3-1.9)<br />

O119 months 22 14 1.9 (0.9-4.0) 2.4 (1.1-5.3)<br />

Missing duration 3 5<br />

Progestin only<br />

Ever use 7 1 6.9 (0.8-57.3) 6.7 (0.8-57.9)<br />

Testosterone<br />

Ever use 9 13 0.7 (0.3-1.6) 0.6 (0.3-1.6)<br />

* ORs (odds ratios) adjusted for age <strong>and</strong> race using logistic regression modeling.<br />

y ORs adjusted for age, race, parity, tubal ligation, hysterectomy, BMI 1 year before interview, 1st degree family history <strong>of</strong> breast or <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>,<br />

breastfeeding (yes/no), oral contraceptive use (yes/no), <strong>and</strong> educational level using logistic regression modeling.

80 Moorman et al<br />

Table IV Odds ratios* for <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> associated with hormone use by type <strong>of</strong> hormone <strong>and</strong> histologic subtype <strong>of</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong><br />

Controls<br />

Serous Endometrioid or clear cell Mucinous Other<br />

n n OR 95% CI n OR 95% CI n OR 95% CI n OR 95% CI<br />

Never user 152 68 1.0 (reference) 31 1.0 (reference) 13 1.0 (reference) 17 1.0 (reference)<br />

Estrogen only 79 73 2.0 (1.3-3.1) 17 1.0 (0.5-2.0) 6 0.9 (0.3-2.5) 9 1.1 (0.5-2.7)<br />

Estrogen always with 87 48 1.1 (0.7-1.8) 9 0.4 (0.2-0.9) 5 0.4 (0.1-1.3) 8 1.0 (0.4-2.4)<br />

progestin<br />

Estrogen <strong>and</strong> progestin,<br />

not always used together<br />

38 27 1.4 (0.8-2.5) 8 0.9 (0.4-2.1) 2 0.4 (0.1-2.0) 7 2.0 (0.7-5.4)<br />

* All ORs adjusted for age <strong>and</strong> race using logistic regression modeling.<br />

significant, the characteristics <strong>of</strong> the cases <strong>and</strong> controls<br />

were generally consistent with established <strong>risk</strong> factors<br />

for <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>. Cases tended to have fewer months<br />

<strong>of</strong> pregnancy, were less likely to have had a tubal<br />

ligation, were more likely to have a family history <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>, <strong>and</strong> had higher educational levels. In<br />

contrast to many studies, we observed little difference in<br />

oral contraceptive use between cases <strong>and</strong> controls.<br />

When comparing characteristics <strong>of</strong> hormone users<br />

<strong>and</strong> nonusers among the control women, we found few<br />

significant differences (data not shown). However, the<br />

trends were consistent with published data, suggesting<br />

that hormone users are more likely to be nulliparous,<br />

have used oral contraceptives, have lower BMI, have<br />

higher educational level, <strong>and</strong> drink alcohol.<br />

Table II shows the ORs for <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> associated<br />

with use <strong>of</strong> any type <strong>of</strong> menopausal <strong>hormones</strong>. There<br />

was not a statistically significant relationship between<br />

ever use <strong>of</strong> menopausal <strong>hormones</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>.<br />

There was a suggestion <strong>of</strong> a modestly increased <strong>risk</strong> for<br />

women who reported long-term use, but no clear<br />

relationship with time since last use. Because we<br />

hypothesized that the effects <strong>of</strong> <strong>hormones</strong> on <strong>ovarian</strong><br />

<strong>cancer</strong> could vary by the specific regimen used, we<br />

examined various categories <strong>of</strong> hormone use separately<br />

(Table III). The OR associated with ever use <strong>of</strong> estrogen<br />

only was only slightly elevated; however, analyses by<br />

duration <strong>of</strong> use showed significantly increased ORs with<br />

longer duration <strong>of</strong> use (P for trend = .03). Ovarian<br />

<strong>cancer</strong> cases were twice as likely to report 10 years or<br />

more <strong>of</strong> unopposed estrogen use as the control women.<br />

There was no suggestion <strong>of</strong> increased <strong>risk</strong> for women<br />

who had taken estrogen <strong>and</strong> progestin always in<br />

combination, whether considering ever use or duration<br />

<strong>of</strong> use. Among women who had taken both estrogen <strong>and</strong><br />

progestin but not always at the same time, there was no<br />

clear trend with duration <strong>of</strong> use. This was a diverse<br />

exposure category in which some <strong>of</strong> the women took<br />

a progestin for nearly all <strong>of</strong> the time when they took<br />

estrogen, whereas other women took progestins for<br />

relatively short periods <strong>of</strong> time <strong>and</strong> were mostly exposed<br />

to unopposed estrogen. There were no significant<br />

associations with use <strong>of</strong> progestin alone (which was<br />

taken by only 7 cases <strong>and</strong> 1 control) or with testosterone<br />

(which was taken by 9 cases <strong>and</strong> 13 controls <strong>and</strong> was<br />

always taken in combination with estrogen <strong>and</strong>/or<br />

progestin).<br />

Table IV shows associations between the hormone<br />

regimens <strong>and</strong> histologic subtypes <strong>of</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>.<br />

Among users <strong>of</strong> estrogen only, the elevated <strong>risk</strong> was<br />

confined to the serous subtype, with no indication <strong>of</strong><br />

increased <strong>risk</strong> in other histologic types. There was not<br />

a strong indication <strong>of</strong> increased <strong>risk</strong> within any histologic<br />

subtype among users <strong>of</strong> estrogen <strong>and</strong> progestin. It<br />

must be noted that with the exception <strong>of</strong> the serous<br />

subtype there was a small number <strong>of</strong> cases within any<br />

given category defined by histology <strong>and</strong> hormone use.<br />

Therefore, it is difficult to say whether some <strong>of</strong> the<br />

observed differences in the ORs by histologic type were<br />

true differences or chance variation due to the small<br />

numbers.<br />

Comment<br />

Analyses from this population-based, case-control study<br />

showed no association between <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

menopausal hormone use overall, but suggested that<br />

long-term users <strong>of</strong> unopposed estrogen may be at increased<br />

<strong>risk</strong>. Although these findings are consistent with<br />

some studies reporting increased <strong>risk</strong> for long-term<br />

users, 7,11,21 the overall picture <strong>of</strong> the relationship between<br />

estrogen use <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> is far from consistent,<br />

with a number <strong>of</strong> studies finding no increased <strong>risk</strong> for<br />

hormone users. At a biological level, the relationship<br />

between estrogens <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> is similarly unclear.<br />

It has been shown that both normal <strong>and</strong> malignant<br />

<strong>ovarian</strong> epithelial cells have estrogen receptors; however,<br />

in vitro studies have not consistently found that estradiol<br />

increases proliferation <strong>of</strong> the <strong>ovarian</strong> epithelium. 9 Our<br />

findings suggested that any increased <strong>risk</strong> related to<br />

estrogen use was confined to the serous histologic subtype.<br />

Some investigators have reported a similar increase<br />

in <strong>risk</strong> for the serous subtype, 7,13,14 but they tended to report<br />

increased <strong>risk</strong> for endometrioid tumors as well. 7,13-15<br />

We saw no indication <strong>of</strong> increased <strong>risk</strong> for endometrioid

Moorman et al 81<br />

or clear cell tumors; however, we had few women with<br />

these histologic subtypes.<br />

Women who reported taking estrogen always with<br />

progestin did not appear to be at increased <strong>risk</strong>. The<br />

overall lack <strong>of</strong> association with combination estrogenprogestin<br />

therapy is consistent with the hypothesis that<br />

progestin protects against <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>. 19,20 The wellestablished<br />

protective effects <strong>of</strong> pregnancy or oral<br />

contraceptive use are beyond what can be explained<br />

simply through suppression <strong>of</strong> ovulation, <strong>and</strong> it has<br />

been suggested that high progesterone levels during<br />

pregnancy <strong>and</strong> the progestin component <strong>of</strong> oral contraceptives<br />

contribute significantly to reducing <strong>ovarian</strong><br />

<strong>cancer</strong> <strong>risk</strong>. 19,22 A possible mechanism for the protective<br />

effect <strong>of</strong> progestins was demonstrated in an in vivo study<br />

that showed that the progestin component <strong>of</strong> oral<br />

contraceptives has a potent apoptotic effect on the<br />

<strong>ovarian</strong> epithelium. 20 It must be noted, however, that<br />

the lack <strong>of</strong> association between <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

estrogen-progestin therapy that we observed contrasts<br />

with recently published findings from the Women’s<br />

Health Initiative r<strong>and</strong>omized clinical trial in which there<br />

was a suggestion <strong>of</strong> increased <strong>risk</strong> associated with<br />

estrogen plus progestin use (hazard ratio 1.58; 95% CI<br />

0.77–3.24) based on a total <strong>of</strong> 32 cases <strong>of</strong> invasive<br />

<strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>. 12<br />

The overall findings from the Women’s Health<br />

Initiative, in which the <strong>risk</strong>s for coronary heart disease,<br />

stroke, pulmonary embolism, <strong>and</strong> breast <strong>cancer</strong> were all<br />

statistically significantly elevated among estrogen plus<br />

progestin users, 23 have resulted in changes in recommendations<br />

for use <strong>of</strong> menopausal <strong>hormones</strong>. Given the<br />

observed lack <strong>of</strong> benefit for cardiovascular conditions,<br />

there is no longer a strong justification for long-term use<br />

<strong>of</strong> menopausal <strong>hormones</strong> for prevention <strong>of</strong> chronic<br />

diseases, <strong>and</strong> many women discontinued them after<br />

publication <strong>of</strong> the Women’s Health Initiative findings.<br />

Current recommendations for use <strong>of</strong> estrogen <strong>and</strong>/or<br />

progestin limited to short-term treatment <strong>of</strong> menopausal<br />

symptoms with the lowest effective dose 24 would not be<br />

expected to have an important effect on <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong><br />

<strong>risk</strong> based on our findings <strong>and</strong> the findings <strong>of</strong> most other<br />

studies, in which any increased <strong>risk</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong><br />

seemed to be most pronounced among long-term users.<br />

An important strength <strong>of</strong> this study was that we were<br />

able to examine different hormone regimens in relation<br />

to <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> <strong>risk</strong>. However, our analyses were<br />

somewhat limited by the number <strong>of</strong> women who had<br />

taken any specific regimen, which prevented us from<br />

more thoroughly considering issues <strong>of</strong> latency, recency,<br />

<strong>and</strong> duration <strong>of</strong> use with any given hormone regimen.<br />

Another limitation was in our ability to do race-specific<br />

analyses. Although our study population was closer to<br />

the US population in terms <strong>of</strong> representation <strong>of</strong> African<br />

Americans (approximately 14%) than many other<br />

studies that have addressed this question, the number<br />

<strong>of</strong> African Americans was still too low to do meaningful<br />

analyses.<br />

Although it would be expected that in the future there<br />

should be relatively few women who would have exposure<br />

to the patterns <strong>of</strong> menopausal hormone use that would<br />

likely increase their <strong>risk</strong> for <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>, clinicians<br />

should be aware <strong>of</strong> the past histories <strong>of</strong> hormone use<br />

among their patients. Based on data suggesting both<br />

a latency effect <strong>of</strong> 10 or more years <strong>and</strong> a persistence <strong>of</strong><br />

effect such that users continue to be at increased <strong>risk</strong> for<br />

some years after stopping <strong>hormones</strong>, 25 it is important that<br />

women <strong>and</strong> their physicians be alert to possible <strong>risk</strong>s for<br />

<strong>cancer</strong> among long-term users <strong>of</strong> menopausal <strong>hormones</strong>,<br />

particularly among women who used unopposed estrogens.<br />

References<br />

1. Weiss NS, Cook LS, Farrow DC, Rosenblatt KA. Ovarian <strong>cancer</strong>.<br />

In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr, editors. Cancer epidemiology<br />

<strong>and</strong> prevention, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996.<br />

p. 1040-57.<br />

2. Riman T, Persson I, Nilsson S. Hormonal aspects <strong>of</strong> epithelial<br />

<strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>: review <strong>of</strong> epidemiological evidence. Clin Endocrinol<br />

1998;49:695-707.<br />

3. Hempling RE, Wong C, Piver MS, Natarajan N, Mettlin CJ.<br />

Hormone replacement therapy as a <strong>risk</strong> factor for epithelial<br />

<strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>: results <strong>of</strong> a case-control study. Obstet Gynecol<br />

1997;89:1012-6.<br />

4. Negri E, Tzonou A, Beral V, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Parazzini<br />

F, et al. Hormonal therapy for menopause <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> in<br />

a collaborative re-analysis <strong>of</strong> European studies. Int J Cancer<br />

1999;80:848-51.<br />

5. Chiaffarino F, Pelucchi C, Parazzini F, Negri E, Franceschi S,<br />

Talamini R, et al. Reproductive <strong>and</strong> hormonal factors <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong><br />

<strong>cancer</strong>. Ann Oncol 2001;12:337-41.<br />

6. Tavani A, Ricci E, LaVecchia C, Surace M, Benzi G, Parazzini F,<br />

et al. Influence <strong>of</strong> menstrual <strong>and</strong> reproductive factors on <strong>ovarian</strong><br />

<strong>cancer</strong> <strong>risk</strong> in women with <strong>and</strong> without family history <strong>of</strong> breast or<br />

<strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>. Int J Epidemiol 2000;29:799-802.<br />

7. Riman T, Dickman PW, Nilsson S, Correia N, Nordlinder H,<br />

Magnusson CM, et al. Hormone replacement therapy <strong>and</strong> the <strong>risk</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> invasive epithelial <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> in Swedish women. J Natl<br />

Cancer Inst 2002;94:497-504.<br />

8. Bosetti C, Negri E, Franceschi S, Trichopoulos D, Beral V,<br />

LaVecchia C. Relationship between postmenopausal hormone<br />

replacement therapy <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>. JAMA 2001;285:3089-90.<br />

9. Sit ASY, Modugno F, Weissfeld JL, Berga SL, Ness RB. Hormone<br />

replacement therapy formulations <strong>and</strong> <strong>risk</strong> <strong>of</strong> epithelial <strong>ovarian</strong><br />

carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2002;86:118-23.<br />

10. Lacey JV Jr, Mink PJ, Lubin JH, Sherman ME, Troisi R, Hartge<br />

P, et al. <strong>Menopausal</strong> hormone replacement therapy <strong>and</strong> <strong>risk</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>. JAMA 2002;288:334-41.<br />

11. Rodriguez C, Patel AV, Calle EE, Jacob EJ, Thun MJ. Estrogen<br />

replacement therapy <strong>and</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> mortality in a large<br />

prospective study <strong>of</strong> US women. JAMA 2001;285:1460-5.<br />

12. Anderson GL, Judd HL, Kaunitz AM, Barad DH, Beresford SAA,<br />

Pettinger M, et al, for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators.<br />

Effects <strong>of</strong> estrogen plus progestin on gynecologic <strong>cancer</strong>s <strong>and</strong><br />

associated diagnostic procedures. JAMA 2003;290:1739-48.<br />

13. Risch HA, Marrett LD, Jain M, Howe GR. Differences in <strong>risk</strong><br />

factors for epithelial <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> by histologic type. Am J<br />

Epidemiol 1996;144:363-72.

82 Moorman et al<br />

14. Weiss NS, Lyon JL, Krishnamurthy S, Dietert SE, Liff JM, Daling<br />

JR. Noncontraceptive estrogen use <strong>and</strong> the occurrence <strong>of</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong><br />

<strong>cancer</strong>. J Natl Cancer Inst 1982;68:95-8.<br />

15. LaVecchia C, Liberati A, Franceschi S. Noncontraceptive estrogen<br />

use <strong>and</strong> the occurrence <strong>of</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>. J Natl Cancer Inst<br />

1982;69:1207.<br />

16. Smith DC, Prentice R, Thompson DJ, Herrmann WL. Association<br />

<strong>of</strong> exogenous estrogen <strong>and</strong> endometrial carcinoma. N Engl J Med<br />

1975;293:1164-7.<br />

17. Kennedy DL, Baum C, Forbes MB. Noncontraceptive estrogens <strong>and</strong><br />

progestins: use patterns over time. Obstet Gynecol 1985;65:441-6.<br />

18. Wysowski DK, Golden L, Burke L. Use <strong>of</strong> menopausal estrogens<br />

<strong>and</strong> medroxyprogesterone in the United States, 1982-1992. Obstet<br />

Gynecol 1995;85:6-10.<br />

19. Risch HA. Hormonal etiology <strong>of</strong> epithelial <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong>, with<br />

a hypothesis concerning the role <strong>of</strong> <strong>and</strong>rogens <strong>and</strong> progesterone. J<br />

Natl Cancer Inst 1998;90:1774-86.<br />

20. Rodriguez GC, Walmer DK, Cline M, Krigman H, Lessey BA,<br />

Whitaker RS, et al. Effect <strong>of</strong> progestin on the <strong>ovarian</strong> epithelium <strong>of</strong><br />

macaques: <strong>cancer</strong> prevention through apoptosis? J Soc Gynecol<br />

Investig 1998;5:271-6.<br />

21. Cramer DW, Hutchison GB, Welch WR, Scully RE, Ryan KJ.<br />

Determinants <strong>of</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> <strong>risk</strong>. I. Reproductive experiences<br />

<strong>and</strong> family history. J Natl Cancer Inst 1983;71:711-6.<br />

22. Schildkraut JM, Calingaert B, Marchbanks PA, Moorman PG,<br />

Rodriguez GC. Impact <strong>of</strong> progestin <strong>and</strong> estrogen<br />

potency in oral contraceptives on <strong>ovarian</strong> <strong>cancer</strong> <strong>risk</strong>. J Natl<br />

Cancer Inst 2002;94:32-8.<br />

23. Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators.<br />

Risks <strong>and</strong> benefits <strong>of</strong> estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal<br />

women. Principal results from the Women’s Health<br />

Initiative R<strong>and</strong>omized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2002;288:321-33.<br />

24. US Food <strong>and</strong> Drug Administration FDA Talk Paper. FDA plans<br />

to evaluate results <strong>of</strong> Women’s Health Initiative study for<br />

estrogen-alone therapy. Accessed: August 15, 2004. http://www.<br />

fda.gov/bbs/topics/ANSWERS/2004/ANS01281.html<br />

25. Risch HA. Hormone replacement therapy <strong>and</strong> the <strong>risk</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>ovarian</strong><br />

<strong>cancer</strong>. Gynecol Oncol 2002;86:115-7.