Four Stories - World Vision Canada Church Engagement

Four Stories - World Vision Canada Church Engagement

Four Stories - World Vision Canada Church Engagement

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Abolition 2013 – <strong>Four</strong> <strong>Stories</strong><br />

Yong – A Trafficking Story<br />

Laos<br />

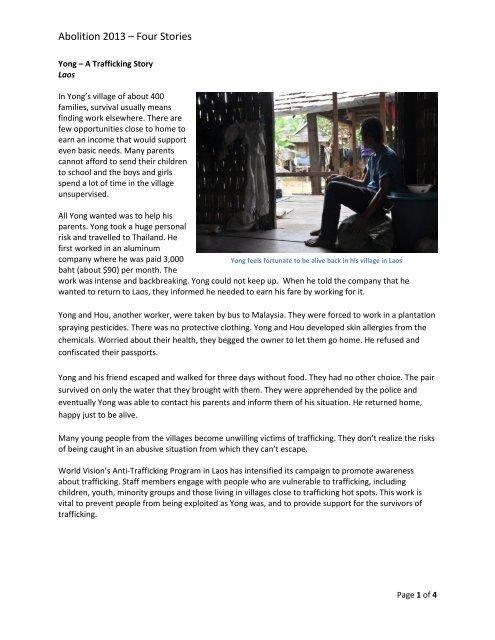

In Yong’s village of about 400<br />

families, survival usually means<br />

finding work elsewhere. There are<br />

few opportunities close to home to<br />

earn an income that would support<br />

even basic needs. Many parents<br />

cannot afford to send their children<br />

to school and the boys and girls<br />

spend a lot of time in the village<br />

unsupervised.<br />

All Yong wanted was to help his<br />

parents. Yong took a huge personal<br />

risk and travelled to Thailand. He<br />

first worked in an aluminum<br />

company where he was paid 3,000<br />

Yong feels fortunate to be alive back in his village in Laos<br />

baht (about $90) per month. The<br />

work was intense and backbreaking. Yong could not keep up. When he told the company that he<br />

wanted to return to Laos, they informed he needed to earn his fare by working for it.<br />

Yong and Hou, another worker, were taken by bus to Malaysia. They were forced to work in a plantation<br />

spraying pesticides. There was no protective clothing. Yong and Hou developed skin allergies from the<br />

chemicals. Worried about their health, they begged the owner to let them go home. He refused and<br />

confiscated their passports.<br />

Yong and his friend escaped and walked for three days without food. They had no other choice. The pair<br />

survived on only the water that they brought with them. They were apprehended by the police and<br />

eventually Yong was able to contact his parents and inform them of his situation. He returned home,<br />

happy just to be alive.<br />

Many young people from the villages become unwilling victims of trafficking. They don’t realize the risks<br />

of being caught in an abusive situation from which they can’t escape.<br />

<strong>World</strong> <strong>Vision</strong>’s Anti-Trafficking Program in Laos has intensified its campaign to promote awareness<br />

about trafficking. Staff members engage with people who are vulnerable to trafficking, including<br />

children, youth, minority groups and those living in villages close to trafficking hot spots. This work is<br />

vital to prevent people from being exploited as Yong was, and to provide support for the survivors of<br />

trafficking.<br />

Page 1 of 4

Abolition 2013 – <strong>Four</strong> <strong>Stories</strong><br />

Two <strong>Stories</strong> from Latin America<br />

Sonite Edmond, Haiti<br />

Sonite Edmond, age 14, is now in her third year of<br />

secondary education at Tamarin National School,<br />

on the island of La Gonave, Haiti. But just a few<br />

years ago, the possibility of studying was only a<br />

distant dream.<br />

Sonite worked as a “restavek,” or domestic<br />

labourer, in a relative's home in Port-au-Prince.<br />

Sonite’s family was in the situation that many<br />

Haitians find themselves. Unable to afford school<br />

fees or the cost of uniforms and books, they send<br />

Children at the L'Ecole National de Tamarin, in Haiti, built<br />

with the help of <strong>World</strong> <strong>Vision</strong> supporters<br />

their children to the city to work. What seems like the only solution in a difficult situation soon becomes<br />

an entrenched pattern. Children work long hours in domestic work and are treated as second-class<br />

citizens. They miss out on schooling and have little hope of escaping their difficult lives.<br />

<strong>World</strong> <strong>Vision</strong>'s sponsorship program became Sonite’s bridge to hope. Now, Sonite and her brother<br />

attend Tamarin School. “It's not fair that some kids get to go to school and others don't,” says Sonite.<br />

“As long as I'm alive I'd like to keep going to school. I want to keep learning, because without this you're<br />

nothing." For Sonite, there is no turning back.<br />

Mayra and her boys, Ecuador<br />

In a cocoa-producing area of rural Ecuador, Mayra was concerned that their family income would not be<br />

enough to keep her children in school. “I always wanted my children to study because if you don’t study,<br />

you are nobody,” says Mayra. But her husband’s seasonal work only brought in $50-$60 a week during<br />

good times—and nothing at all for up to three months in winter.<br />

Mayra and other women in her community looked for ways to<br />

change their situation. Together, they joined a <strong>World</strong> <strong>Vision</strong><br />

project promoting fair-trade goods.<br />

The 20 women learned how to make cocoa cakes, cocoa<br />

powder, chocolates and candies. They learned business skills<br />

and how to market their products. A few months later the<br />

women opened their fair trade business, contributing part of<br />

the set-up investment themselves. "It seemed impossible to<br />

gather the money but we saved our earnings,” recalls Mayra.<br />

<strong>World</strong> <strong>Vision</strong> contributed equipment and materials to support<br />

the women, and helped get their products to markets in Quito,<br />

the capital city. Two years after the business started up, Mayra<br />

earns around $30-$40 a month. She uses the money to keep<br />

her sons in school. “I’m so proud,” says Mayra, “because<br />

nobody ever thought this could be possible.”<br />

A community-run fair trade cocoa business helps<br />

keep Mayra's sons in school<br />

Page 2 of 4

Abolition 2013 – <strong>Four</strong> <strong>Stories</strong><br />

Alphonsine and Her Children<br />

Democratic Republic of Congo<br />

Every day, Alphonsine Ngolo, 37,<br />

and five of her children go to the<br />

copper mining quarry in<br />

Kambove, [southern Congo] to<br />

work. The area is baked in sun<br />

and constantly dusty. They wear<br />

no protective clothing.<br />

Sometimes they even forego the<br />

relative comfort of hand-medown<br />

sandals to work more<br />

efficiently barefoot.<br />

Alphonsine and her kids dig up<br />

and clean rocks to see if they can<br />

Alphonsine (background) and children spend their days in the copper quarry<br />

get a sellable amount of raw<br />

copper. They have to work through a large quantity of the discarded soil and rock to find the greenish<br />

copper pieces. Then they clean the raw copper for selling. On a good day they might pull together<br />

enough copper ore to earn the equivalent of $3. That money mostly goes to food.<br />

"My husband is sick on the bed two years now and nobody is assisting my family with food and soap.<br />

[That is] why I decided to work in the mining here, children assisting me, as they don't have [anything] to<br />

do at home," Alphonsine says.<br />

The area is responsible for<br />

producing thousands of metric<br />

tonnes of copper a year, but has<br />

no health centre or school.<br />

Alphonsine and her family are<br />

caught in the system. Their only<br />

option is to work in the mine.<br />

One of Alphonsine's daughters sifting for raw copper in the quarry<br />

The <strong>World</strong> <strong>Vision</strong> Congo and<br />

<strong>Canada</strong> offices are currently<br />

working with local government<br />

officials to ensure that<br />

development in the area takes<br />

into account the needs of<br />

families in Alphonsine’s<br />

community and others like it.<br />

Page 3 of 4

Abolition 2013 – <strong>Four</strong> <strong>Stories</strong><br />

Jonaki’s Story<br />

Bangladesh<br />

Eleven-year-old Jonaki lives with her parents<br />

and younger sister in northern Bangladesh. Her<br />

father is a small teashop-keeper. Her mother<br />

works at home. They did not earn enough to<br />

meet the family’s needs and the family often<br />

went to bed hungry. Her parents did not have<br />

enough money for school and Jonaki, at only<br />

nine years old, spent her days in a ‘Bidi’<br />

(pronounced “beedi”) factory where she made<br />

hand-made cigarettes from unrefined tobacco<br />

leaves.<br />

Jonaki and her family preparing a meal at home<br />

Bidi making is dirty, punishing work in dust-filled factories. Workers face serious health risks, like severe<br />

muscle strain and respiratory illnesses. They spend their days working quickly to roll tobacco flakes in<br />

paper or a tobacco leaf, tie off the ends and then use a sharp knife to finish off the crude cigarettes.<br />

They must roll their quota of 1000 bidis each day to take home less than one dollar at the end of a 12<br />

hour shift. For Jonaki, the choice was to roll bidis or go hungry.<br />

“Life was not easy for me. It was hard grinding all day. I have been mistreated and manhandled at times<br />

by my employers. I had to work from dawn to dusk and never had the chance to go to school. I was<br />

totally illiterate,” Jonaki says.<br />

Jonaki joined the Non-formal Primary Education (NFPE) Program in 2010 under the Child Rescue Project.<br />

She now regularly attends classes and is a good student. “Once I joined <strong>World</strong> <strong>Vision</strong>’s NFPE Program, I<br />

never looked back,” Jonaki says. “This was a<br />

once in a lifetime opportunity. I did not want<br />

to lose it at any cost. I grabbed it with both<br />

hands!”<br />

The <strong>World</strong> <strong>Vision</strong> program is also making<br />

deeper changes. “As I participate in various<br />

awareness sessions on child rights and<br />

protection issues and, as well, other factors<br />

related to under-age marriage, trafficking,<br />

abuse etc., I can now firmly justify that<br />

equality is the key to protecting myself and<br />

bringing a better life,” Jonaki says.<br />

Jonaki has embraced education "with both hands!"<br />

Page 4 of 4

![Download the Red Letters Bible Study guide [PDF] - World Vision ...](https://img.yumpu.com/38523640/1/185x260/download-the-red-letters-bible-study-guide-pdf-world-vision-.jpg?quality=85)