What is libel by implication? - Directrouter.com

What is libel by implication? - Directrouter.com

What is libel by implication? - Directrouter.com

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

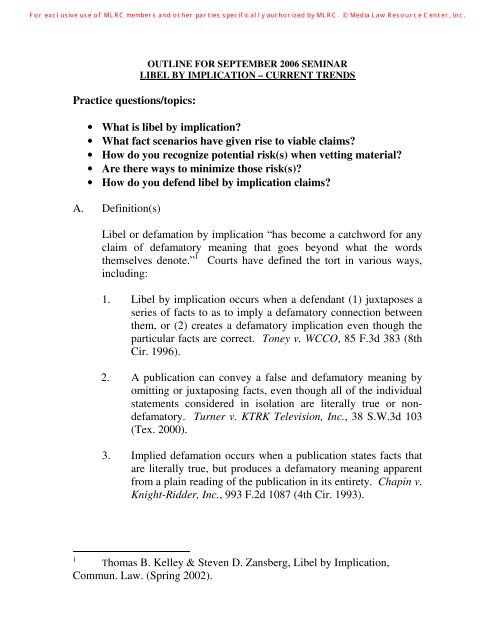

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized <strong>by</strong> MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc.<br />

Practice questions/topics:<br />

OUTLINE FOR SEPTEMBER 2006 SEMINAR<br />

LIBEL BY IMPLICATION – CURRENT TRENDS<br />

• <strong>What</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>libel</strong> <strong>by</strong> <strong>implication</strong>?<br />

• <strong>What</strong> fact scenarios have given r<strong>is</strong>e to viable claims?<br />

• How do you recognize potential r<strong>is</strong>k(s) when vetting material?<br />

• Are there ways to minimize those r<strong>is</strong>k(s)?<br />

• How do you defend <strong>libel</strong> <strong>by</strong> <strong>implication</strong> claims?<br />

A. Definition(s)<br />

Libel or defamation <strong>by</strong> <strong>implication</strong> “has be<strong>com</strong>e a catchword for any<br />

claim of defamatory meaning that goes beyond what the words<br />

themselves denote.” 1 Courts have defined the tort in various ways,<br />

including:<br />

1. Libel <strong>by</strong> <strong>implication</strong> occurs when a defendant (1) juxtaposes a<br />

series of facts to as to imply a defamatory connection between<br />

them, or (2) creates a defamatory <strong>implication</strong> even though the<br />

particular facts are correct. Toney v. WCCO, 85 F.3d 383 (8th<br />

Cir. 1996).<br />

2. A publication can convey a false and defamatory meaning <strong>by</strong><br />

omitting or juxtaposing facts, even though all of the individual<br />

statements considered in <strong>is</strong>olation are literally true or nondefamatory.<br />

Turner v. KTRK Telev<strong>is</strong>ion, Inc., 38 S.W.3d 103<br />

(Tex. 2000).<br />

3. Implied defamation occurs when a publication states facts that<br />

are literally true, but produces a defamatory meaning apparent<br />

from a plain reading of the publication in its entirety. Chapin v.<br />

Knight-Ridder, Inc., 993 F.2d 1087 (4th Cir. 1993).<br />

1<br />

Thomas B. Kelley & Steven D. Zansberg, Libel <strong>by</strong> Implication,<br />

Commun. Law. (Spring 2002).

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized <strong>by</strong> MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc.<br />

B. Fact patterns resulting in viable claims<br />

Libel <strong>by</strong> <strong>implication</strong> recently has been found in a various fact<br />

scenarios, which can be generally categorized as follows:<br />

1. False <strong>implication</strong>s ar<strong>is</strong>ing from true facts:<br />

a. Stevens v. Iowa Newspapers, Inc., 711 N.W. 2d 732<br />

(Table), 2006 WL 126626, 34 Med. L. Rep. 1430 (Iowa<br />

Ct. App. 2006): Plaintiff, a freelance sports writer, sued<br />

the Ames Tribune and a sports writer alleging defamation<br />

ar<strong>is</strong>ing from a column which criticized plaintiff’s<br />

journal<strong>is</strong>tic practices in response to an earlier column<br />

plaintiff had written. The trial court entered summary<br />

judgment in favor of defendants. On appeal, after<br />

concluding that the column’s statement that plaintiff<br />

“rarely attended events upon which he wrote columns”<br />

was “literally true” and “not directly defamatory,” the<br />

court held the statement was actionable. Specifically, the<br />

court found that a “reasonable juror” could find that the<br />

sports writer intended to convey the defamatory message<br />

that plaintiff was professionally in<strong>com</strong>petent. The court<br />

based its ruling in part on the sports writer’s<br />

testimony that, although the statement was not intended<br />

as a <strong>com</strong>ment on plaintiff’s professional credibility, it<br />

was intended to express that plaintiff often offered<br />

opinions which had no bas<strong>is</strong> in fact or research.<br />

b. Johnson v. Columbia Broad. Sys., Inc., 10 F. Supp. 2d<br />

1071 (D. Minn. 1998): Plaintiff, a cosmetic surgeon,<br />

sued a telev<strong>is</strong>ion station ar<strong>is</strong>ing from a broadcast about<br />

h<strong>is</strong> practice entitled “Scarred for Life.” Because the<br />

alleged defamation arose from statements implied from,<br />

rather than directly contained in, the broadcast, the court<br />

required plaintiff to establ<strong>is</strong>h that the broadcast was<br />

capable of being interpreted as alleged and that defendant<br />

intended the alleged <strong>implication</strong>s. To resolve these<br />

questions, the court used a five-step analys<strong>is</strong>: (1) <strong>is</strong> the<br />

alleged statement capable of being proved true or false;<br />

(2) <strong>is</strong> the relevant portion of the broadcast susceptible to<br />

2

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized <strong>by</strong> MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc.<br />

the <strong>implication</strong> alleged; (3) did defendant intend the<br />

alleged <strong>implication</strong>; (4) <strong>is</strong> the alleged <strong>implication</strong> in fact<br />

false; and (5) would a person in the exerc<strong>is</strong>e of<br />

reasonable care have known the <strong>implication</strong> was false?<br />

Applying th<strong>is</strong> analys<strong>is</strong>, the court found the found the<br />

broadcast contained several actionable <strong>implication</strong>s<br />

which should be determined <strong>by</strong> a jury. In th<strong>is</strong> regard, the<br />

court found that there were “fact <strong>is</strong>sues” as to defendant’s<br />

intent ra<strong>is</strong>ed <strong>by</strong> the “context” and “tenor” of the<br />

broadcast.<br />

2. Juxtaposition and om<strong>is</strong>sion:<br />

a. West v. Media General Operations, Inc., 120 F. App’x.<br />

601, 33 Med. L. Rep. 1321 (6th Cir. 2005): Plaintiffs, a<br />

probation counseling center and its owner, sued a<br />

telev<strong>is</strong>ion station for defamation ar<strong>is</strong>ing from a 4-part<br />

investigative series detailing the “cozy relationship”<br />

between the center and local judges entitled “Probation<br />

for Sale.” After a jury awarded damages, the telev<strong>is</strong>ion<br />

station appealed. Although the Sixth Circuit reversed the<br />

award on other grounds, it held that plaintiffs were<br />

entitled to sue on various implied “topics” ar<strong>is</strong>ing from<br />

defendant’s alleged juxtaposition of v<strong>is</strong>ual and audio<br />

<strong>com</strong>ponents. Plaintiffs were not required to identify<br />

specific statements contained in the broadcast which they<br />

alleged were defamatory. In so ruling, the Court stated<br />

that the “video context” in which a statement <strong>is</strong> made<br />

must be examined because “a telev<strong>is</strong>ion director or<br />

reporter can, in many subtle ways, alter the tone and<br />

meaning of an otherw<strong>is</strong>e innocuous broadcast through<br />

video and audio editing techniques.” Accordingly, a<br />

telev<strong>is</strong>ion news report can “imply a defamatory<br />

statement” not specifically stated through a <strong>com</strong>bination<br />

of statements and v<strong>is</strong>ual effects.<br />

b. Franklin Prescriptions, Inc. v. The New York Times Co.,<br />

267 F. Supp. 2d 425 (E. D. Pa. 2003): Plaintiff pharmacy<br />

sued for defamation ar<strong>is</strong>ing from an article concerning<br />

unscrupulous online pharmacies, which take e-mail<br />

3

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized <strong>by</strong> MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc.<br />

orders for controlled and other drugs without requiring a<br />

prescription. Although there was no specific reference to<br />

plaintiff within the article, it did contain an edited version<br />

of plaintiff’s “web-grab” (a printout of plaintiff’s website<br />

used as photograph). The court denied defendant’s<br />

motion for summary judgment, ruling that the<br />

juxtaposition of plaintiff’s web-grab without explanatory<br />

information included in plaintiff’s website regarding the<br />

necessity of having a prescription “could lead a<br />

reasonable person to believe that [plaintiff] engages in<br />

the exact type of conduct described” in the article.<br />

Because the plaintiff was a private figure, the court<br />

refused to require plaintiff to prove that defendant<br />

endorsed the defamatory <strong>implication</strong>.<br />

c. Turner v. KTRK Telev<strong>is</strong>ion, Inc., 38 S.W.3d 103 (Tex.<br />

2000): Plaintiff mayoral candidate sued telev<strong>is</strong>ion station<br />

for <strong>libel</strong> ar<strong>is</strong>ing from news broadcast questioning h<strong>is</strong> role<br />

in a life insurance scam. Although the Texas Supreme<br />

Court affirmed the reversal of a jury verdict in plaintiff’s<br />

favor, it held that plaintiff could state a cause of action<br />

for implied defamation based on the “publication as a<br />

whole” rather than on specific false statements. In so<br />

ruling, the court identified several key facts omitted from<br />

the broadcast which would have more accurately<br />

portrayed plaintiff’s role in the transaction at <strong>is</strong>sue. By<br />

omitting these facts, and falsely juxtaposing others, the<br />

“broadcast’s m<strong>is</strong>leading account cast more suspicion on<br />

[plaintiff’s] conduct than a substantially true account<br />

would have done.”<br />

3. False <strong>implication</strong>s from false facts and/or opinions<br />

a. Hatfill v. The New York Times Co., 416 F.3d 320 (4th<br />

Cir. 2005): Plaintiff sued for defamation and other<br />

claims ar<strong>is</strong>ing from a series of columns which ra<strong>is</strong>ed<br />

questions and expressed opinions about the FBI’s<br />

investigation of the anthrax mailings. Plaintiff asserted<br />

that the columns falsely implied that he was involved in<br />

the mailings. The circuit court reversed the d<strong>is</strong>trict court<br />

4

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized <strong>by</strong> MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc.<br />

d<strong>is</strong>m<strong>is</strong>sal of the action, ruling that a defamatory charge<br />

may be made expressly or <strong>by</strong> “inference, <strong>implication</strong> or<br />

insinuation.” The court held that the columns, taken<br />

together, focused only on plaintiff, which likely would<br />

lead a reasonable reader to conclude that plaintiff was<br />

responsible for the mailings. Moreover, th<strong>is</strong><br />

“unm<strong>is</strong>takable theme” was not sufficiently clarified <strong>by</strong><br />

the column<strong>is</strong>t’s caution to readers that plaintiff should be<br />

presumed innocent, or h<strong>is</strong> statement that the FBI should<br />

either arrest or clear plaintiff.<br />

b. Schlieman v. Gannett Minnesota Broad., Inc., 637<br />

N.W.2d 297 (Minn. Ct. App. 2001): Plaintiff police<br />

officer sued telev<strong>is</strong>ion station alleging defamation <strong>by</strong><br />

<strong>implication</strong> ar<strong>is</strong>ing from an investigative news report<br />

about the shooting of a citizen. In considering the lower<br />

court’s jury instruction barring consideration of whether<br />

juxtaposition or om<strong>is</strong>sion was a bas<strong>is</strong> to find defamation<br />

<strong>by</strong> <strong>implication</strong> because of plaintiff’s status as a public<br />

figure, the court held that the instruction was defective.<br />

In so ruling, the court d<strong>is</strong>tingu<strong>is</strong>hed earlier rulings which<br />

establ<strong>is</strong>hed that a public-official plaintiff could not base a<br />

defamation <strong>by</strong> <strong>implication</strong> claim on true statements.<br />

Specifically, the court held that defamatory meaning<br />

should be d<strong>is</strong>tinct from falsity for purposes of proving a<br />

defamation <strong>by</strong> <strong>implication</strong> claim based on false facts, and<br />

plaintiff accordingly could rely on juxtaposition and<br />

omitted facts to find defamatory meaning.<br />

c. Gjonlekaj v. SOT, 308 A.D.2d 471 (N. Y. App. Div.<br />

2003): Plaintiff, a publ<strong>is</strong>her of a rival Albanian<br />

newspaper, sued h<strong>is</strong> <strong>com</strong>petitor for <strong>libel</strong> ar<strong>is</strong>ing from a<br />

news article which concerned plaintiff’s alleged claim of<br />

sole credit for the idea of publ<strong>is</strong>hing an Albanian<br />

translation of a book written <strong>by</strong> Pope John Paul II. The<br />

article at <strong>is</strong>sue characterized plaintiff as a “left<strong>is</strong>t<br />

bookseller” who dealt in Commun<strong>is</strong>t propaganda in<br />

Albania. The article further stated that many “newly<br />

arrived Albanians don’t know [plaintiff’s] background,<br />

but to many of us who know him very well he <strong>is</strong> a<br />

5

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized <strong>by</strong> MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc.<br />

representative of Marx<strong>is</strong>t ideology” which was<br />

destructive to Albania. The court denied defendant’s<br />

motion to d<strong>is</strong>m<strong>is</strong>s, holding that these statements implied<br />

that defendant had knowledge of certain facts not known<br />

to readers which supported h<strong>is</strong> defamatory opinion<br />

regarding plaintiff.<br />

C. Libel <strong>by</strong> <strong>implication</strong> d<strong>is</strong>gu<strong>is</strong>ed as false light<br />

1. False light <strong>is</strong> a form of invasion of privacy which <strong>is</strong> actionable<br />

where a publication places an individual <strong>is</strong> a “false light” before<br />

the public if (a) the false light <strong>is</strong> highly unreasonable; and (2)<br />

the publ<strong>is</strong>her had knowledge of or acted in reckless d<strong>is</strong>regard<br />

as to the falsity of the publicized matter and the false light in<br />

which the individual would be placed. Restatement (Second) of<br />

Torts §652(E) (1977).<br />

2. Th<strong>is</strong> language unfortunately has led some courts to declare that<br />

false light does not require a false statement of fact, only a<br />

statement placing a person in a false light. See, e.g., Heekin v.<br />

CBS Broad., Inc., 789 So. 2d 355 (Fla. 2d DCA 2001);<br />

Goodbehere v. Phoenix Newspapers, 783 P.2d 781 (Ariz.<br />

1989). Th<strong>is</strong> concept has opened the door for claims based on<br />

implied meaning, which typically would not survive scrutiny<br />

under traditional defamation standards, or where <strong>com</strong>panion<br />

defamation claims fail. For example:<br />

a. Anderson v. Gannett Co., Inc., et al., Case No. 2001-CA-<br />

1728, First Judicial Circuit Court, Escambia County,<br />

Florida: In Anderson, the plaintiff <strong>is</strong> the owner and<br />

founder of a large road paving <strong>com</strong>pany -- Anderson<br />

Columbia -- based on Lake City, Florida. During a fiveday<br />

period in December 1998, the defendant Pensacola<br />

News Journal publ<strong>is</strong>hed a series of articles concerning<br />

problems between Anderson Columbia and state<br />

regulators. One of the stories in the series reported on<br />

Anderson Columbia’s political contributions and<br />

d<strong>is</strong>cussed a pending federal grand jury investigation of<br />

the <strong>com</strong>pany’s political connections. The article also<br />

reported that Joe Anderson had been indicted <strong>by</strong> an<br />

6

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized <strong>by</strong> MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc.<br />

D. Defenses<br />

earlier federal grand jury and charged with bribing local<br />

government officials to obtain road work. Anderson<br />

pleaded guilty to mail fraud and was sentenced to<br />

probation. The article also accurately reported that<br />

Anderson’s probation was extended because he had<br />

“shot and killed h<strong>is</strong> wife” with a shotgun he was barred<br />

from possessing. The article’s next sentence explains<br />

where the death occurred and that Joe Anderson had filed<br />

for divorce, followed <strong>by</strong> a sentence that stated: “Law<br />

enforcement officials determined the shooting was a<br />

hunting accident.” Based primarily on these three<br />

sentences, plaintiff sued for false light alleging although<br />

the article was literally true, it placed him in a false light<br />

as having murdered h<strong>is</strong> wife. Following a lengthy trial, a<br />

jury found in Anderson’s favor and awarded him more<br />

than $18 million. An appeal of the verdict currently <strong>is</strong><br />

pending in Florida’s First D<strong>is</strong>trict Court of Appeal.<br />

Even where <strong>libel</strong> <strong>by</strong> <strong>implication</strong> and related torts have been<br />

recognized as a viable claims, courts have employed traditional,<br />

constitutionally-based and tort-specific defenses in rejecting such<br />

claims. For example,<br />

1. Truth<br />

a. Nichols v. Moore, 396 F. Supp. 2d 783 (E.D. Mich.<br />

2005): Plaintiff, the brother of Oklahoma City Bomber<br />

Terry Nichols, sued for defamation <strong>by</strong> <strong>implication</strong> and<br />

false light ar<strong>is</strong>ing from defendant’s documentary film<br />

regarding guns and violence in Anerica. The court<br />

granted summary judgment on plaintiff’s defamation<br />

claims, finding that he failed to demonstrate the<br />

publication contained false statements, <strong>implication</strong>s or<br />

omitted material factual statements. Plaintiff’s false light<br />

and emotional d<strong>is</strong>tress claims failed for the same reasons.<br />

b. Mohr v. Grant, 108 P.3d 768 (Wash. 2005): Plaintiffs,<br />

the owners of an interior design firm, sued a telev<strong>is</strong>ion<br />

7

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized <strong>by</strong> MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc.<br />

station for defamation ar<strong>is</strong>ing from broadcasts<br />

concerning the arrest and prosecution of an mentallyhandicapped<br />

individual ar<strong>is</strong>ing from an incident at<br />

plaintiffs’ store. Plaintiffs alleged inter alia that<br />

defendant omitted material facts which resulted in<br />

defamation <strong>by</strong> <strong>implication</strong>. The court ruled that the<br />

telev<strong>is</strong>ion station was entitled to summary judgment<br />

because plaintiff failed to establ<strong>is</strong>h falsity, i.e., that the<br />

alleged false impression conveyed <strong>by</strong> the broadcasts<br />

would be contradicted <strong>by</strong> the inclusion of omitted facts.<br />

Specifically, the court found that the omitted information<br />

would not have negated the alleged defamatory<br />

<strong>implication</strong> in its entirety, and the broadcasts therefore<br />

were not actionable.<br />

c. Proskin v. Hearst Corp., 14 A.D.3d 782 (N.Y. App. Div.<br />

2005): Plaintiff, a former d<strong>is</strong>trict attorney and judge,<br />

sued newspaper for defamation ar<strong>is</strong>ing from article<br />

reporting h<strong>is</strong> criminal conviction had been overturned<br />

based on ineffective ass<strong>is</strong>tance of counsel. The article<br />

reported that h<strong>is</strong> career had stalled after public<br />

revelations that he had altered a client’s will to leave her<br />

money to h<strong>is</strong> own children. The court rejected plaintiff’s<br />

allegation that the article implied h<strong>is</strong> actions were<br />

criminal and defamed him because it failed to state that<br />

he altered the will at the client’s request. Rather, the<br />

court held that because the article did not affirmatively<br />

state plaintiff had done anything illegal or criminal,<br />

plaintiff’s defamation claim must fail.<br />

d. Montefusco v. ESPN, Inc., 47 F. App’x. 124, 2002 WL<br />

31108927, 30 Med. L. Rep. 2311 (3d Cir. 2002):<br />

Plaintiff, a former major league baseball player, sued for<br />

defamation and false light ar<strong>is</strong>ing from an ESPN<br />

broadcast which reported concerned criminal charges<br />

against plaintiff connection with sexual and physical<br />

violence toward h<strong>is</strong> ex-wife. Plaintiff alleged that the<br />

broadcast’s <strong>com</strong>par<strong>is</strong>on of plaintiff to O.J. Simpson<br />

falsely implied that he was guilty of crimes of which he<br />

had been acquitted. The court d<strong>is</strong>m<strong>is</strong>sed the action,<br />

8

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized <strong>by</strong> MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc.<br />

ruling that all of the statements reported were factually<br />

accurate, as was the <strong>com</strong>par<strong>is</strong>on to O.J. Simpson.<br />

e. Am. Transm<strong>is</strong>sion, Inc. v. Channel 7 of Detroit, Inc., 609<br />

N.W.2d 607 (Mich. Ct. App. 2000): Plaintiff<br />

transm<strong>is</strong>sion repair shop sued telev<strong>is</strong>ion station and<br />

reporter for defamation and other claims ar<strong>is</strong>ing from<br />

investigative report concerning deceptive practices at<br />

shop. Although the statements in the broadcast were<br />

true, plaintiff asserted the entire broadcast was<br />

defamatory because it implied plaintiff was d<strong>is</strong>honest.<br />

The court affirmed summary judgment in defendants’<br />

favor, ruling that plaintiff had failed to establ<strong>is</strong>h the any<br />

<strong>implication</strong>s ra<strong>is</strong>ed <strong>by</strong> the broadcast were false.<br />

2. Implication(s) not reasonable<br />

a. Rubin v. U.S. News & World Report, Inc., 271 F.3d 1305<br />

(11th Cir. 2001): Plaintiff, the owner of a gold-refining<br />

business, sued magazine for <strong>libel</strong> ar<strong>is</strong>ing from report<br />

concerning drug trafficking in the international gold<br />

trade. The Eleventh Circuit affirmed the d<strong>is</strong>trict court’s<br />

d<strong>is</strong>m<strong>is</strong>sal of the action, holding that no “reasonable<br />

reading of the text supports the <strong>implication</strong>” that plaintiff<br />

was engaged in improper conduct, and that the use of h<strong>is</strong><br />

photograph failed to create any defamatory <strong>implication</strong>.<br />

Although not necessary to its holding, the court<br />

recognized that “a First Amendment problem <strong>is</strong><br />

encountered when a private figure <strong>com</strong>plains that he has<br />

been defamed <strong>by</strong> <strong>implication</strong> in a <strong>com</strong>munication<br />

containing only true facts.”<br />

b. Worrell-Payne v. Gannett Co., Inc., 134 F. Supp. 2d<br />

1167 (D. Idaho 2000): Plaintiff, a former director of<br />

local housing authority, sued newspaper for <strong>libel</strong> <strong>by</strong><br />

<strong>implication</strong> and related torts ar<strong>is</strong>ing from news articles<br />

critical of plaintiff’s performance. The court granted<br />

summary judgment in favor of defendant, holding that<br />

the articles at <strong>is</strong>sue were “not reasonably capable of<br />

sustaining the false <strong>implication</strong>s” alleged <strong>by</strong> plaintiff.<br />

9

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized <strong>by</strong> MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc.<br />

3. No intent/endorsement<br />

a. Thomas v. Los Angeles Times Communications LLC, 45<br />

F. App’x. 801, 2002 WL 31007420, 30 Med. L. Rep.<br />

2438 (9th Cir. 2002): Plaintiff sued newspaper for<br />

defamation ar<strong>is</strong>ing from article about plaintiff’s life story<br />

which he alleged implied that he had lied about previous<br />

exploits and that h<strong>is</strong> language instruction program was a<br />

sham. The court affirmed d<strong>is</strong>m<strong>is</strong>sal of the action, ruling<br />

that even if plaintiff could show the articles were capable<br />

of the defamatory <strong>implication</strong>s, he had failed to establ<strong>is</strong>h<br />

that the author had intended those <strong>implication</strong>s.<br />

b. Abadian v. Lee, 117 F. Supp. 2d 481 (D. Md. 2000):<br />

Plaintiff health club manager sued fitness magazine for<br />

defamation and related claims ar<strong>is</strong>ing from quotes <strong>by</strong> her<br />

contained in an article entitled regarding practices<br />

consumers should be aware of and/or avoid in connection<br />

with health club memberships. The court d<strong>is</strong>m<strong>is</strong>sed<br />

plaintiff’s action, ruling that she could not establ<strong>is</strong>h that<br />

the articles statements and om<strong>is</strong>sions affirmatively<br />

suggested the author intended or endorsed the defamatory<br />

<strong>implication</strong>s.<br />

2. Use of d<strong>is</strong>claimer(s)<br />

a. Leddy v. Narrangansett Telev<strong>is</strong>ion, L.P., 843 A.2d 481<br />

(R.I. 2004): Plaintiff, a fire marshall, sued a telev<strong>is</strong>ion<br />

station for defamation ar<strong>is</strong>ing from an investigative series<br />

concerning d<strong>is</strong>ability pensions paid to firefighters and<br />

police officers which contained an interview with him.<br />

The court affirmed summary judgment in favor of<br />

defendants, ruling that the broadcasts did not<br />

<strong>com</strong>municate any false statements about plaintiff or<br />

imply the ex<strong>is</strong>tence of defamatory facts about him. The<br />

court based its ruling largely on the d<strong>is</strong>claimer at the<br />

beginning of the broadcast which expressly stated that<br />

the report “was not implying plaintiff had done anything<br />

illegal.”<br />

10