The Evolution of Retirement by J. Ignacio Conde-Ruiz* Vincenzo ...

The Evolution of Retirement by J. Ignacio Conde-Ruiz* Vincenzo ...

The Evolution of Retirement by J. Ignacio Conde-Ruiz* Vincenzo ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Evolution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Retirement</strong><br />

<strong>by</strong><br />

J. <strong>Ignacio</strong> <strong>Conde</strong>-<strong>Ruiz*</strong><br />

<strong>Vincenzo</strong> Galasso**<br />

Paola Pr<strong>of</strong>eta***<br />

DOCUMENTO DE TRABAJO 2005-03<br />

February 2005<br />

* Prime Minister’s Economic Bureau and FEDEA.<br />

** IGIER, Universit`a Bocconi and CEPR.<br />

*** Università di Pavia and Università Bocconi.<br />

Los Documentos de trabajo se distribuyen gratuitamente a las Universidades e Instituciones de Investigación que lo solicitan. No obstante están<br />

disponibles en texto completo a través de Internet: http://www.fedea.es/hojas/publicaciones.html#Documentos de Trabajo<br />

<strong>The</strong>se Working Documents are distributed free <strong>of</strong> charge to University Department and other Research Centres. <strong>The</strong>y are also available through<br />

Internet: http://www.fedea.es/hojas/publicaciones.html#Documentos de Trabajo

Depósito Legal: M-2958-2005

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Evolution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Retirement</strong> ∗<br />

J. <strong>Ignacio</strong> <strong>Conde</strong>-Ruiz<br />

Prime Minister’s Economic Bureau and FEDEA<br />

<strong>Vincenzo</strong> Galasso<br />

IGIER, Università Bocconi and CEPR<br />

Paola Pr<strong>of</strong>eta,<br />

Università di Pavia and Università Bocconi<br />

February 2005.<br />

Abstract<br />

We provide a long term perspective on the individual retirement behavior<br />

and on the future <strong>of</strong> early retirement. In a cross-country sample, we<br />

find that total pension spending depends positively on the degree <strong>of</strong> early<br />

retirement and on the share <strong>of</strong> elderly in the population, which increase<br />

the proportion <strong>of</strong> retirees, but has hardly any effect on the per-capita pension<br />

benefits. We show that in a Markovian political economic theoretical<br />

framework, in which incentives to retire early are embedded, a political<br />

equilibrium is characterized <strong>by</strong> an increasing sequence <strong>of</strong> social security<br />

contribution rates converging to a steady state and early retirement. Comparative<br />

statics suggest that aging and productivity slow-downs lead to<br />

higher taxes and more early retirement. However, when income effects<br />

are factored in, the model suggests that periods <strong>of</strong> stagnation — characterized<br />

<strong>by</strong> decreasing labor income — may lead middle aged individuals to<br />

postpone retirement.<br />

Keywords: pensions, lifetime income effect, tax burden, politicoeconomic<br />

Markovian equilibrium<br />

JEL Classification: H53, H55, D72<br />

∗ Paola Pr<strong>of</strong>eta, paola.pr<strong>of</strong>eta@unibocconi.it. Jose <strong>Ignacio</strong> <strong>Conde</strong>-Ruiz, jiconde@presidencia.gob.es;<br />

<strong>Vincenzo</strong> Galasso, vincenzo.galasso@unibocconi.it. We thank<br />

J.F.Jimeno for many useful comments and suggestions, G.Casamatta, P. Poutvaara and<br />

participants to the Fourth CEPR/RTN workshop “Financing <strong>Retirement</strong> in Europe” at<br />

CORE, Louvain-la-Neuve and to the 2004 Annual Meeting <strong>of</strong> the IIPF. All remaining errors<br />

are ours. Part <strong>of</strong> this paper was written while P.Pr<strong>of</strong>eta was research fellow at CORE,<br />

Université Catholique de Louvain, under the CEPR-RTN Project “Financing <strong>Retirement</strong><br />

in Europe”. Financial support from Fundación Ramon Areces and Fundación BBVA is<br />

gratefully acknowledged. <strong>The</strong> views expressed herein are those <strong>of</strong> the authors and not<br />

necessarily those <strong>of</strong> the Spanish Prime Minister’s Economic Bureau.<br />

1

1 Introduction<br />

<strong>Retirement</strong> decisions represent one <strong>of</strong> the hottest issues <strong>of</strong> the current social<br />

security debate. Several studies - see Blondal and Scarpetta (1998) and Gruber<br />

and Wise (1999 and 2003) among the most recent work - have suggested that<br />

individual retirement decisions are strongly affected <strong>by</strong> the design <strong>of</strong> the social<br />

security system. In particular, individuals tend to retire either as soon as they<br />

are given the opportunity, i.e., at early retirement age, or at normal retirement<br />

age. Moreover, most social security systems have been proven to provide strong<br />

incentives - in terms <strong>of</strong> large implicit taxes on continuing to work - to anticipate<br />

retirement. In taking their retirement decisions, most individuals prefer to enjoy<br />

generous early retirement benefits - and the leisure associated with an early exit<br />

from the labor market - rather then to continue working, since, in the latter<br />

case, their additional contributions to the system would not sufficiently increase<br />

their future pension benefits.<br />

Several studies have made an additional step <strong>by</strong> arguing that the massive<br />

use <strong>of</strong> early retirement provisions has come at a cost: the deterioration <strong>of</strong> the<br />

financial sustainability <strong>of</strong> the system, already under stress because <strong>of</strong> population<br />

aging. In fact, several international organizations - such as the European<br />

Union at the 2001 Lisbon Meetings - have advocated an increase in the effective<br />

retirement age, or - analogously - the increase in the activity rate among individuals<br />

aged above 55 years, as a key policy measure to control the rise in social<br />

security expenditure. In a nutshell, the postponement <strong>of</strong> the retirement age has<br />

become a milestone in all social security reform’s proposals. However, whether<br />

these policy prescriptions will actually be adopted depends on the politics <strong>of</strong><br />

early retirement (see Cremer and Pestieau 2000, Fenge and Pestieau, 2005, for<br />

a detailed discussion <strong>of</strong> early retirement issues, and Galasso and Pr<strong>of</strong>eta, 2002,<br />

for a more general survey <strong>of</strong> the political economy <strong>of</strong> social security).<br />

2

In this paper, we aim at providing a long term perspective on the individual<br />

retirement behavior. We start from the role played at present <strong>by</strong> retirement<br />

decisions in social security and we analyze implications for the future <strong>of</strong> early<br />

retirement.<br />

First, we address the relation between the use <strong>of</strong> the early retirement provisions<br />

and the pension expenditure in a cross-country sample to evaluate the<br />

impact <strong>of</strong> the effective retirement age on the level <strong>of</strong> pension expenditure. We<br />

find that the total size <strong>of</strong> pension expenditure depends positively on different<br />

measures <strong>of</strong> early retirement, on the share <strong>of</strong> elderly in the population and on<br />

per capita GDP. To better investigate these relations, we decompose the total<br />

pension expenditure over GDP in the number <strong>of</strong> pensioners over total population<br />

and the average pension over per capita GDP. We find that early retirement<br />

shows a positive relation with the number <strong>of</strong> elderly, but hardly any relation<br />

with the average pension.<br />

Second, we provide a simple theoretical framework in which the incentives to<br />

retire early - as identified <strong>by</strong> Blondal and Scarpetta (1998) and Gruber and Wise<br />

(1999 and 2003) - are examined in conjunction with some long term determinants<br />

<strong>of</strong> the retirement decision.<br />

We use a Markovian politico-economic model to<br />

predict the equilibrium path <strong>of</strong> fiscal policies over social security. We find a<br />

political equilibrium characterized <strong>by</strong> an increasing sequence <strong>of</strong> social security<br />

tax rates converging to a steady state and <strong>by</strong> a parallel increment in the use<br />

<strong>of</strong> early retirement provisions. Comparative statics suggest that aging will lead<br />

to higher taxes and more early retirement. However, when income effects are<br />

factored in, the model suggests that period <strong>of</strong> stagnation — characterized <strong>by</strong><br />

decreasing labor income — may lead middle aged individuals to increase their<br />

labor supply and hence reduce early retirement.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re exists a vast literature on retirement decisions. Already two decades<br />

ago, Feldstein (1974) and Boskin (1977) analyzing the determinants <strong>of</strong> the de-<br />

3

cline in the labor force participation <strong>of</strong> elderly workers pointed at two key parameters<br />

<strong>of</strong> social security systems: the income guarantee and the implicit tax<br />

on earnings.<br />

Endogenous retirement decisions have been analyzed <strong>by</strong> showing<br />

how pensions systems introduce distortions in the labor supply choice (see<br />

among others Diamond and Mirrless, 1978, Hu, 1979, Crawford and Lilien,<br />

1981, and Michel and Pestieau, 1999). <strong>The</strong> empirical literature <strong>of</strong> the effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> social security design on retirement includes Boskin and Hurd (1978), Hurd<br />

and Boskin (1984), Diamond and Housman (1984), and more recently Gruber<br />

and Wise (1999 and 2003) and Blondal and Scarpetta (1998). A new literature<br />

has lately emerged on the political economy <strong>of</strong> early retirement (see Fenge and<br />

Pestieau, 2004, Lacomba and Lagos, 2000, Casamatta et al., 2002, <strong>Conde</strong>-Ruiz<br />

and Galasso, 2003 and 2004, Cremer and Pestieau 2003), although generally neglecting<br />

the role <strong>of</strong> income effects. Markovian politico-economic models <strong>of</strong> social<br />

security have been recently studied <strong>by</strong> Azariadis and Galasso (2002), Hassler et<br />

al (2003), Gonzalez-Eiras and Niepelt (2004) and Forni (2005).<br />

<strong>The</strong> paper is structured as follows.<br />

In the next section, we address the<br />

relation between retirement decisions and social security expenditure in a crosscountry<br />

sample. Section 3 presents a Markovian politico economic model, in<br />

which individual retirement decisions and the evolution <strong>of</strong> social security and<br />

early retirement are analyzed. Section 4 concludes.<br />

2 Some Evidence on <strong>Retirement</strong> and Pension<br />

Expenditures<br />

<strong>The</strong> relation between retirement and social security has been largely analyzed<br />

(see Latulippe, 1997, and Gruber and Wise, 1999 and 2003, among many others).<br />

<strong>The</strong> social security system may induce early exit from the labor market before<br />

collecting pension benefits or may provide large incentives to retire early. It<br />

is however worth noticing that the relation between retirement behavior and<br />

4

social security expenditure seems to depend crucially on the number <strong>of</strong> elderly<br />

in the population (see Pr<strong>of</strong>eta 2002). In fact, in countries with a large share <strong>of</strong><br />

elderly in the population, the effective labor force participation <strong>of</strong> the elderly<br />

tends to be low. <strong>The</strong>se countries are also associated with a large total pension<br />

expenditure.<br />

What are then the main determinants <strong>of</strong> social security expenditures? And<br />

in particular, what is the role <strong>of</strong> the retirement behavior?<br />

To answer these<br />

questions, we build a large data set collecting information on demographics,<br />

retirement and social security for many countries around the world and perform<br />

a simple cross-country analysis.<br />

Asdemographicvariableweusetheproportion<strong>of</strong>elderly(individualsaged<br />

more than 65 years) in the total population (OLD), taken from the United Nations<br />

Demographics Yearbook (1999). From the Yearbook <strong>of</strong> Labor Statistics<br />

<strong>of</strong> the International Labour Office (1985-2000) we construct two variables that<br />

measure the effective retirement age: (i) the average activity rate in the period<br />

1985-2000 for individuals between 55 and 64 years old (ACTOT for all and<br />

ACTOTM for man) and (ii) the difference between the average activity rate<br />

in the period 1985-2000 for individuals between 40 and 55 years old (AC1TOT<br />

for all and AC1M for man) and the average activity rates for individuals between<br />

55 and 64 years old (DAC for all and DACM for man). This last variable<br />

(DAC) represents a measure <strong>of</strong> the extent <strong>of</strong> early retirement, <strong>by</strong> capturing the<br />

drop in the activity rate from age 40-55 to age 55-64. From the International<br />

Monetary Fund Government Finance Statistics Yearbook (several years in the<br />

period 1986-1998) we obtain the average level in the period 1986-1998 <strong>of</strong> pension<br />

expenditures as percentage <strong>of</strong> GDP (PENSEXP) 1 .Finally,fromtheILO<br />

World Labour Report (2000) we obtain the percentage <strong>of</strong> pensioners over total<br />

1 Notice that the IMF’s definition <strong>of</strong> social security includes old age payments, and therefore<br />

it differs from an ideal measure <strong>of</strong> “governments transfers to the elderly”, because it excludes<br />

medical and other subsidies for the elderly.<br />

5

population (NUMPENS). Combining this information and the level <strong>of</strong> pension<br />

expenditures as percentage <strong>of</strong> GDP, we calculate the per capita average pension<br />

(AVPENS).<br />

Table 1 provides some simple statistics <strong>of</strong> our variables.<br />

We perform a simple cross-country regression. Table 2 summarizes the results<br />

for a sample <strong>of</strong> all countries for which the data are available 2 and table<br />

3 for a sub-sample <strong>of</strong> OECD countries 3 . <strong>The</strong> level <strong>of</strong> pension expenditures as<br />

percentage <strong>of</strong> GDP depends significantly and positively on the number <strong>of</strong> elderly<br />

andonGDP,andsignificantly but negatively on the activity rate <strong>of</strong> individuals<br />

between 55 and 64 years old (column (a)). According to this result, countries<br />

with a larger share <strong>of</strong> elderly in their populations spend more for pensions, as<br />

intuitively expected. Richer countries also spend more in pension, as predicted<br />

<strong>by</strong> Wagner’s law. Finally, countries where the effective retirement age is higher<br />

(i.e. individuals between 55 and 64 years old have higher activity rates) spend<br />

less in pensions. <strong>The</strong>se determinants together explain most <strong>of</strong> the variability in<br />

pension expenditures (R*2=0.837). To obtain a better measure <strong>of</strong> early retirement,<br />

we use the variable DAC, which represents the reduction <strong>of</strong> the activity<br />

rate <strong>of</strong> individuals between 55 and 64 years old with respect to the activity rate<br />

<strong>of</strong> people in age 40-55. This measure <strong>of</strong> early retirement is significantly and<br />

positively related to the level <strong>of</strong> pension expenditures (column (b)), suggesting<br />

that countries which use more early retirement spend more for pensions.<br />

A<br />

2 Albania, Algeria, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Bahamas, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Barbados,<br />

Belarus, Belgium, Belize, Benin, Bolivia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Cape Verde, Central<br />

African Republic, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic,<br />

Denmark, Dominica, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Estonia, Ethiopia, Fiji, Finland, France,<br />

Germany, Greece, Grenada, Guatemala, Guyana, Hungary, Iceland, Indonesia, Iran, Ireland,<br />

Israel, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Mauritius,<br />

Mexico, Moldova, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Norway, Pakistan,<br />

Panama, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Senegal, Singapore, Slovakia, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden,<br />

Switzerland, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States,<br />

Uruguay.<br />

3 Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czeck Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany,<br />

Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand,<br />

Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States.<br />

6

similar result is obtained if we restrict to the activity rates <strong>of</strong> man (column (c)).<br />

To better understand the determinants <strong>of</strong> the level <strong>of</strong> pension expenditures<br />

and the role played <strong>by</strong> each <strong>of</strong> the identified variables, as pointed out <strong>by</strong> Jimeno<br />

(2002a, 2002b) we use the following identity:<br />

PENSEXP = NUMPENS ∗ AV P ENS<br />

which makes clear how the level <strong>of</strong> pension expenditures as percentage <strong>of</strong> GDP is<br />

the product <strong>of</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> pensioners as a proportion <strong>of</strong> total population and<br />

<strong>of</strong> the average pension in terms <strong>of</strong> GDP per capita. According to this decomposition,<br />

the role played <strong>by</strong> the demographic variable (the proportion <strong>of</strong> elderly in<br />

the population) and the retirement variables (the measures <strong>of</strong> early retirement)<br />

in explaining the level <strong>of</strong> pension expenditures can be better understand using<br />

two additional sets <strong>of</strong> regressions. Due to limited information on the number<br />

<strong>of</strong> pensioners and the average pension, we perform these regressions only using<br />

thesample<strong>of</strong>allcountries.<br />

First, we try to estimate the determinants <strong>of</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> pensioners,<br />

as shown in table 4.<br />

Clearly, countries where there are more elderly in the<br />

population have more pensioners (OLD is positively and significantly related<br />

to NUMPENS). Countries where there is more early retirement have also more<br />

pensioners (ACTOT is negatively and significantly related to PENSEXP in<br />

column (a) and DAC negatively and significantly in column (b)). This regression<br />

makes clear that both the proportion <strong>of</strong> elderly in total population and early<br />

retirement increase the level <strong>of</strong> pension expenditures through the increase <strong>of</strong><br />

the number <strong>of</strong> pensioners. Second, we estimate the impact <strong>of</strong> demographics and<br />

retirement on the level <strong>of</strong> average pension. Table 5 shows that neither aging<br />

(OLD) nor early retirement (DAC) are significant in explaining the average<br />

pension.<br />

To summarize, these simple results suggest that while more elderly and lower<br />

7

early retirement increase the overall pension expenditures, via asignificant increase<br />

<strong>of</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> retirees, they do not affect the per capita average pension.<br />

In the following section we introduce a political economy model which is<br />

able to account for these facts.<br />

3 A politico-economic model<br />

3.1 <strong>The</strong> economic Environment<br />

We consider a simple three -period overlapping generations model. Every period<br />

three generations are alive, we call them respectively young, adult and old.<br />

Young face a labor-leisure trade <strong>of</strong>f on the intensive margin. <strong>The</strong>y choose how<br />

many hours <strong>of</strong> work to supply, receive a wage, w y , pay a payroll tax on labour<br />

income, τ , and save all their disposable income for old age consumption. <strong>The</strong>re<br />

exists a storage technology that transforms a unit <strong>of</strong> today’s consumption into<br />

1+r units <strong>of</strong> tomorrow’s consumption. All private intertemporal transfers <strong>of</strong><br />

resources into the future are assumed to take place through this technology.<br />

Adult individuals decide what fraction, z, <strong>of</strong> the second period to spend<br />

working; in other words, they decide when to retire. An adult individual who<br />

works a proportion z <strong>of</strong> the second period receives a net labor income equal<br />

to w a (1 − τ), for the fraction z <strong>of</strong> the period.<br />

To simplify the analysis, we<br />

assume that no pension benefit is received for the remaining fraction (1 − z),<br />

during which individuals however enjoy leisure. Finally, all old individuals are<br />

assumed to retire and to obtain a pension, p. Population grows at a rate n.<br />

<strong>The</strong> life time budget constraint for an agent born at time t is then equal to:<br />

c o t+2 =(1− τ t ) l t w y t (1 + r) 2 +(1− τ t+1 ) z t+1 w a t+1 (1 + r)+p t+2 (1)<br />

where c o t+2 is old age consumption at time t+2, l t represents the amount <strong>of</strong> work<br />

supplied <strong>by</strong> a young individual at time t and subscripts indicate the calendar<br />

time. Moreover, τ t and τ t+1 are the pay roll taxes respectively at periods t and<br />

8

t +1andr is the interest rate.<br />

To account for differences in the wages <strong>by</strong> age, i.e., between young and adult<br />

workers, and for economic growth, we characterize the relations between wages<br />

across time and generations as follows: wt+1 a =(1+g) wt a ,whereg is the real<br />

growth rate <strong>of</strong> wages, and w y t<br />

= ϕw a t ,whereϕ defines the ratio between the<br />

wage <strong>of</strong> young and adult workers at time t.<br />

To simplify the analysis, we assume that agents only value life-time income<br />

— or analogously old age consumption, c t+2 — and leisure when young and adult,<br />

according to the following utility function, which has been introduced in a two<br />

periods context <strong>by</strong> Casamatta, Cremer and Pestieau (2002) and Cremer and<br />

Pestieau (2002) to study incentive effects on early retirement provisions:<br />

U (l t ,z t+1 ,c t+2 )=c o t+2 − l2 t<br />

2α wy t − z2 t+1<br />

2γ wa t+1 (2)<br />

where the second and third terms represent the disutility from the effective<br />

labor supply, and α and γ are parameters that quantify the relative importance<br />

<strong>of</strong> leisure when young and adult, and that we take to be equal respectively to<br />

α =1/ (1 + r) 2 and γ =1/ (1 + r). 4<br />

Hence, a young agent at time t and an adult at time t+1 maximize eq. 2 with<br />

respect to l t and z t+1 subject to the budget constraints at eq. 1. <strong>The</strong> solution<br />

<strong>of</strong> the two maximization problems yields the following optimal individual labor<br />

supply decisions:<br />

b lt = 1− τ t (3)<br />

bz t+1 = 1− τ t+1 (4)<br />

We consider a balanced budget pay as you go (PAYG) social security system,<br />

where the sum <strong>of</strong> all pension transfers is equal the sum <strong>of</strong> all contributions. Since<br />

pensions are awarded to elderly individuals only, whereas young and adults<br />

4 <strong>The</strong>se assumptions simplify the analysis. However the main results qualitatively hold true<br />

in more general cases.<br />

9

workers contribute according to their labor income, the full pension transfer at<br />

time t which balances the budget constraint is equal to:<br />

p t = τ t<br />

³<br />

(1 + n t )(1+n t−1 ) w t<br />

b lt +(1+n t−1 ) w a t bz t´<br />

(5)<br />

or equivalently<br />

where w t =((1+n t ) w y t + w a t ).<br />

p t = τ t (1 − τ t )(1+n t−1 ) w t (6)<br />

Finally, <strong>by</strong> substituting the individual decisions at eq.<br />

3 and 4 and the<br />

above social security budget constraint, we derive the following expression for<br />

the indirect utility function <strong>of</strong> an adult individual at time t:<br />

V a (τ t−1 ,τ t ,τ t+1 ) = (1− τ t−1 ) b l t−1 w y t−1 (1 + r)2 +(1− τ t ) bz t w a t (1 + r)+<br />

3.2 <strong>The</strong> Political Equilibrium<br />

+τ t+1 (1 − τ t+1 )(1+n t ) w t+1 − b l 2 t−1<br />

2α wy t−1 − bz2 t<br />

2γ wa t .(7)<br />

<strong>The</strong> purpose <strong>of</strong> this paper is to propose a theoretical framework in which to account<br />

for the link between early retirement provision and the size <strong>of</strong> the social<br />

security system examined in section 2. We have already showed at eq. 4 that<br />

early retirement behavior may be induced <strong>by</strong> specific features<strong>of</strong>thesocialsecurity<br />

system, such as the contribution rate. Here, we analyze the determination<br />

<strong>of</strong> this social security contribution rate within the political arena. We follow<br />

a well established tradition in political economics <strong>by</strong> concentrating on the median<br />

voter decision. Yet, due to the intergenerational nature <strong>of</strong> the system, we<br />

allow for some interdependence between current and future political decisions.<br />

In particular, we analyze Markov perfect equilibrium outcomes <strong>of</strong> a repeated<br />

voting game over the social security contribution rate. Models using subgame<br />

perfection as equilibrium concept identify a large set <strong>of</strong> sequences <strong>of</strong> equilibrium<br />

social security contribution rates that need not to depend on the state on the<br />

10

economy, while in models that concentrate on Markov perfect equilibrium outcomes,<br />

the political decision over the social security contribution rate depends<br />

on the state <strong>of</strong> the economy — typically through the stock <strong>of</strong> capital 5 . Since<br />

the aim <strong>of</strong> the paper is to examine the possible link between the use <strong>of</strong> early<br />

retirement provisions and the size <strong>of</strong> the social security system, we choose to<br />

summarize the state <strong>of</strong> the economy for our Markov equilibrium <strong>by</strong> the share <strong>of</strong><br />

early retirees in the population. This amounts to assume that economies with<br />

the same share <strong>of</strong> early retirees take the same decision on the size <strong>of</strong> the system.<br />

More specifically, at every period t, the median voter in each generation <strong>of</strong><br />

voters — hence typically an adult individual — decides her most favorite social<br />

security system (i.e., the tax rate τ t ). In taking her decision, she expects her<br />

current decision to have an impact <strong>of</strong> future policies. In particular, her expectations<br />

about the future social security tax rate — and hence about her pension<br />

benefits — depend on the current level <strong>of</strong> early retirement, according to a function<br />

τ t+1 = q e (z t ). Hence, future contribution rates depend on the current level<br />

<strong>of</strong> labor force participation <strong>by</strong> the elderly, which is in turn affected <strong>by</strong> the current<br />

voter’s decision over the social security contribution rate. <strong>The</strong>refore, the<br />

median voter´s optimal decision can be obtained maximizing her lifecycle utility<br />

with respect to τ t and given expectations on the next period policy function<br />

τ t+1 = q e (z t )=Q(z t (τ t )):<br />

max V a (τ t−1 ,τ t ,τ t+1 )=maxV a (τ t−1 ,τ t ,Q(z t (τ t ))) (8)<br />

τ t<br />

τ t<br />

We can now define the Markov political equilibrium as follows<br />

Definition 1 A Markov political equilibrium is a pair <strong>of</strong> functions (Q, Z), where<br />

Q :[0, 1] → [0, 1] is a policy rule, τ t = Q(z t−1 ),andZ :[0, 1] → [0, 1] is a private<br />

5 For examples <strong>of</strong> Markov equilibria, see Krusell et al.(1997), Grossman and Helpman<br />

(1998), Bassetto (1999), Azariadis and Galasso (2002), Hassler et al. (2003), Gonzalez-Eiras<br />

and Niepelt (2004), Forni (2005).<br />

11

decision rule, z t =1− τ t = Z(τ t ), such that the following functional equations<br />

hold:<br />

i) Q(z t−1 ) = arg max<br />

τ t<br />

V a (τ t−1 ,τ t ,τ t+1 ) subject to τ t+1 = Q(Z(τ t )).<br />

ii) Z(τ t )=1− τ t<br />

<strong>The</strong> first equilibrium condition requires that τ t maximizes the objective function<br />

<strong>of</strong> the median voter — an adult individual as long as n t (1 + n t−1 ) < 1—<br />

taking into account that the future social security system tax rate, τ t+1 depends<br />

on the current social security tax rate, τ t , via the private labor supply<br />

decision <strong>of</strong> the adults. Furthermore, it requires Q(z t−1 )tobeafixed point in<br />

the functional equation in part i) <strong>of</strong> the definition. In other words, if agents<br />

believe future benefits to be set according to τ t+j = Q(z t+j−1 ), then the same<br />

function Q(z t−1 )hastodefine the optimal voting decision today. <strong>The</strong> second<br />

equilibrium condition requires that all old individuals choose their labor supply<br />

optimally.<br />

In order to compute the Markov political equilibrium, we have to consider<br />

the optimal social security tax rate chosen <strong>by</strong> the median voter at time t, who<br />

maximizes the indirect utility function at eq. 7 with respect to τ t and subject<br />

to τ t+1 = Q(Z(τ t )).<br />

<strong>The</strong> corresponding first order condition is:<br />

−w a t z t (1 + r)+ dp t+1<br />

dτ t+1<br />

Q 0 (z t )Z 0 (τ t )=0 (9)<br />

where Z 0 (τ t )=−1, which suggests that the current cost <strong>of</strong> contributing to the<br />

system has to be compensated <strong>by</strong> a corresponding benefit in the future. <strong>The</strong><br />

solution <strong>of</strong> the maximization problem <strong>of</strong> the median voter yields the optimal<br />

fiscal policies, as summarized in the following proposition.<br />

Proposition 2 <strong>The</strong> set <strong>of</strong> feasible fiscal policies {τ ∗ t } ∞ t=s<br />

∈ [0, 1] which can be<br />

12

supported <strong>by</strong> a Markovian politico-economic equilibrium satisfies:<br />

s<br />

τ t+1 = Q(Z(τ t )) = 1 2 − 1 1 − 2A − 2(1 + r)wa t Z(τ t ) 2<br />

2<br />

(1 + n t )w t+1<br />

where A, the free parameter pinned down <strong>by</strong> the first median voter’s expectation<br />

<strong>of</strong> future policies, is restricted to the support A ∈ [(1 + r)w a t , (1 + n t )w t+1 /2].<br />

Pro<strong>of</strong>. See Appendix.<br />

<strong>The</strong> result in proposition 2 points to the existence <strong>of</strong> a positive link between<br />

thecurrentuse<strong>of</strong>earlyretirementprovisions and the future social security<br />

contribution rate. This link completes the economic chanel running from the<br />

social security contribution rate to the current labor supply decision <strong>of</strong> the<br />

adults, as described at eq. 4. In particular, a current increase in the social<br />

security contribution rate leads to more current early retirement — <strong>by</strong> reducing<br />

the opportunity cost <strong>of</strong> retirement — which in turn creates expectations for more<br />

social security contributions — and hence more early retirement — in the future.<br />

In fact, since z t =1− τ t , the dynamics for the equilibrium policy function<br />

can be described as follows:<br />

τ t+1 = 1 2 − 1 2<br />

s<br />

1 − 2A − 2(1 + r)wa t (1 − τ t ) 2<br />

(1 + n t )w t+1<br />

(10)<br />

Furthermore, it is easy to show that dτ t+1 /dτ t<br />

∈ (0, 1), and thus the equilibrium<br />

path converges to a stable steady state with a positive social security<br />

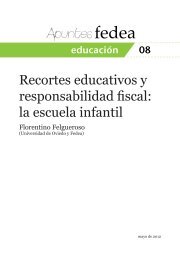

contribution rate — and early retirement. As shown in figure 1, if the initial<br />

social security contribution is below the steady state level, the dynamics feature<br />

an increasing sequence <strong>of</strong> tax rate (and an increasing use <strong>of</strong> early retirement),<br />

which converges to the steady state.<br />

3.3 Aging, Social Security and Early <strong>Retirement</strong><br />

<strong>The</strong> equilibrium policy function obtained in the previous section allows us to<br />

analyze the effects <strong>of</strong> aging on the dynamics <strong>of</strong> the social security tax rate and<br />

13

on the use <strong>of</strong> early retirement.<br />

To see how aging may affect this evolution,<br />

consider the decision <strong>of</strong> the median voter at time t.<br />

When determining the<br />

current social security contribution rate, this adult voter follows the equilibrium<br />

function described at eq. 10 — lagged one period. By setting the policy according<br />

to this function, she validates the expectations <strong>of</strong> the previous median voter,<br />

since she is indifferent on what to vote, provided that she expects the next<br />

median voter to follow the same function in the future.<br />

Consider now that at time t information becomes available that aging will<br />

occur at time t + 1. In other words, at time t, the median voter learns that<br />

population growth will permanently drop from the following period: n t+i 0. Since no change occurs in the policy function at time t —noticefrom<br />

eq. 10 that τ t = Q(Z(τ t−1 )) only depends on n t−1 and on n t —thesocial<br />

security contribution rate will be set in accordance with the expectations <strong>of</strong> the<br />

median voter at time t − 1. Yet, the current median voter’s expectations on the<br />

future social security contribution rate do change because <strong>of</strong> the expected aging<br />

and so will the policy function in the next and in all future periods. <strong>The</strong> next<br />

proposition summarizes the results <strong>of</strong> this expected aging process on the social<br />

security contribution rate and on early retirement.<br />

Proposition 3 Consider an economy at its stable steady state characterized <strong>by</strong><br />

the social security contribution τ, a pension transfer p and <strong>by</strong> z =1− τ. A<br />

permanent decrease in the population growth rate taking place at time t +1,but<br />

anticipated <strong>by</strong> the voters at time t — that is, n t+i 0, withE t (n t+i )=<br />

n t+i — has the following effects:<br />

• at time t +1, it increases the contribution rate, τ t+1 >τ t ,andtheearly<br />

retirement, z t+1<br />

< z t , while leaving the per-capita pension unaffected,<br />

p t+1 = p t ;and<br />

• at steady state, it increases the social security contribution rate — i.e, τ 0 ><br />

14

τ — the use <strong>of</strong> early retirement — i.e., z 0 < z.<br />

Pro<strong>of</strong>. See Appendix.<br />

According to the proposition above, aging leads to higher social security tax<br />

rates and more early retirement, while leaving the per-capita pension transfer<br />

unaffected, at least in the short run.<br />

<strong>The</strong> intuition behind this result is the<br />

following. As the population growth rate drops, the implicit return from a PAYG<br />

social security system decreases as well. Hence, the median voter modifies the<br />

policy function <strong>by</strong> making it more responsive to the past early retirement (and<br />

hence to the past social security contribution rates) in order to compensate the<br />

lower returns with higher contributions. In particular, the median voter at time<br />

t + 1 — that is, when the aging process effectively begins — increases the tax rate<br />

to counterbalance the effect <strong>of</strong> the aging on the pension transfer to the current<br />

elderly, which in fact remains constant. In future periods, until a new steady<br />

state is reached, contribution rates will increase to finance higher social security<br />

spending and to compensate the successive median voters — the adults — for the<br />

higher contributions paid on their labor income. Eventually, at the new steady<br />

state, the contribution rate increases leading to more early retirement.<br />

Another component <strong>of</strong> the returns from social security that has received<br />

large attention in the literature is the growth rate <strong>of</strong> wages, g. In fact, higher<br />

economic growth is <strong>of</strong>ten advocated as a painless solution to the financial sustainability<br />

problems affecting most PAYG social security systems.<br />

Yet, the<br />

political economy literature on social security has pointed out that changes in<br />

economic growth — <strong>by</strong> affecting the social security returns — modify the incentives<br />

faced <strong>by</strong> the voters in deciding the future pension policy.<br />

To see how higher economic growth may affect these dynamics, consider the<br />

decision <strong>of</strong> the median voter, who determines the social security contribution<br />

rate, at time t, when a permanent increase in the economic growth rate takes<br />

15

place, g t+i >g t−1 ∀i ≥ 0. In our Markov perfect equilibrium, the median voter<br />

does not change her voting behavior, in order to validate the expectations <strong>of</strong><br />

the previous median voter. Yet, she expects future median voters to obey to<br />

the new policy function — see eq.<br />

10 — where the new values <strong>of</strong> the growth<br />

rates are taken into account. <strong>The</strong> next proposition summarizes the results <strong>of</strong><br />

this increase in economic growth on the social security contribution rate and on<br />

early retirement.<br />

Proposition 4 Consider an economy at its stable steady state characterized <strong>by</strong><br />

the social security contribution τ and <strong>by</strong> z =1− τ. A permanent increase in<br />

theeconomicgrowthrateattimet —thatis,g t+i >g t−1 ∀i ≥ 0 —decreasesthe<br />

steady state social security contribution rate — i.e, τ 0 < τ —andreducestheuse<br />

<strong>of</strong> early retirement — i.e., z 0 > z.<br />

Pro<strong>of</strong>. See Appendix.<br />

Our Markov political equilibrium hence confirms the conventional (economic)<br />

wisdom that more growth reduces the size <strong>of</strong> the social security system. <strong>The</strong><br />

intuition is similar, yet specular, to the case <strong>of</strong> aging. Higher growth now rises<br />

the implicit returns from a PAYG system. Hence, the pension benefits to the<br />

retirees may be obtained with lower contribution rates, and the policy function<br />

becomes less responsive to the past early retirement (and hence to the past<br />

social security contribution rates).<br />

Eventually, at the new steady state, the<br />

contributionratedropsleadingtoaloweruse <strong>of</strong> the early retirement provisions.<br />

3.4 Social Security, Early <strong>Retirement</strong> and Income Effects<br />

<strong>The</strong> results obtained in the previous section are hardly reassuring. According to<br />

our political economy analysis, aging and productivity slow-downs will lead to<br />

larger social security system and more early retirement. However, the analysis<br />

carried out in the previous sections did not incorporate the possible effect <strong>of</strong><br />

16

changes in income or wealth on the individual early retirement decisions, and<br />

thus on the politically determined social security contribution rate. According<br />

to eq. 4, in fact, retirement decisions only depended on substitution effects —<br />

through the impact <strong>of</strong> the labor tax on continuing to work. Possible income<br />

effects — leading poorer individuals to work longer, i.e., to retire later — were<br />

abstracted from, although several authors (see for instance Costa, 1998) have<br />

suggested that the long lasting decreasingtrendintheretirementagemayat<br />

least partially be due to the major improvements in economic conditions that<br />

increased the demand for leisure, and hence for early retirement.<br />

In this section, we introduce a simple income effect in our economic model.<br />

In particular, we modify the utility function at eq. 2 <strong>by</strong> adding a new term for<br />

the disutility <strong>of</strong> labor which depends on the adult’s wage:<br />

U (l t ,z t+1 ,c t+2 )=c o t+2 − l2 t<br />

2α wy t − z2 t+1<br />

2γ wa t+1 − λz t+1<br />

¡<br />

w<br />

a<br />

t+1<br />

¢ 2<br />

(11)<br />

This modification 6 <strong>of</strong> the previous specification amounts to assume that the<br />

adults’ retirement decision depends negatively on their current income. In fact,<br />

their optimal individual labor supply decision becomes:<br />

bz t+1 =1− τ t+1 − δw a t+1 (12)<br />

where δ = λ∗γ, and the growth rate <strong>of</strong> wages, g, is assumed to be equal to zero.<br />

Thus, low-income adults decide to work for longer periods and richer adult to<br />

retire earlier. This result suggests that, unlike in Cremer and Pestieau (2003),<br />

theincomeeffect may dominate the substitution effect 7 .<br />

Clearly, this change in the retirement behavior <strong>of</strong> adults affects the PAYG<br />

social security systems, since the full pension transfer at time t which balances<br />

6 An alternative, more satisfactory way <strong>of</strong> introducing an income effect in the retirement<br />

decision would be to simply eliminate the linearity from the utility function. Were the utility<br />

function to be concave in the level <strong>of</strong> consumption, the retirement decision would immediately<br />

depend (negatively) on the lifetime income <strong>of</strong> the agent. However, this alternative specification<br />

would not yield a close form solution for the Markov perfect political economic equilibrium.<br />

7 See Jensen et al. (2004).<br />

17

the budget constraint becomes:<br />

h<br />

p t = τ t (1 + n t−1 ) w t (1 − τ t ) − δ (wt a ) 2i . (13)<br />

How does the introduction <strong>of</strong> this negative income effect in the retirement decision<br />

modify the result <strong>of</strong> the Markov political equilibrium described in section<br />

3? In this new scenario, the sequence <strong>of</strong> median voters face a similar political<br />

decisions to the one described in section 3.2, which leads to the following<br />

dynamics for the equilibrium social security contribution rates:<br />

Ã<br />

τ t+1 = 1 1 − δ ¡ ¢<br />

wt+1<br />

a 2<br />

!<br />

+ (14)<br />

2 w t+1<br />

v<br />

− 1 u<br />

Ã<br />

t<br />

1 − δ ¡ ¢<br />

wt+1<br />

a 2<br />

! 2<br />

− 2[A − (1 + r)wa t (1 − τ t − δwt a ) 2 ]<br />

.<br />

2 w t+1 (1 + n t )w t+1<br />

³<br />

with A ∈ [(1 + r)wt a (1 − δwt a ) , (1 + n t ) w t+1 − δ (wt a ) 2´2 /2wt+1 ].<br />

Hence, also in this scenario, the dynamics described at eq. 14 points to the<br />

existence <strong>of</strong> a positive link between the current use <strong>of</strong> early retirement provisions<br />

and the future social security contribution rate. A higher current social security<br />

contribution rate induces more current early retirement — due to the reduction<br />

in the opportunity cost <strong>of</strong> retiring — and creates expectations for more social<br />

security contributions and early retirement in the future. Moreover, as in the<br />

previous case, it is easy to show that dτ t+1 /dτ t ∈ (0, 1), and thus the equilibrium<br />

path converges to a steady state with a positive social security contribution rate<br />

— and early retirement, with equilibrium paths that are qualitatively similar to<br />

the ones shown in figure 1.<br />

<strong>The</strong> discussion above suggests that this scenario, which incorporates an income<br />

effect, features similar properties for the Markov equilibrium outcomes<br />

as in the previous case. However, this new specification allows an analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

the impact <strong>of</strong> a reduction in the adult’s labor income — i.e., a negative income<br />

effect — on the adults’ retirement behavior, in which the effect on the sequence<br />

18

<strong>of</strong> equilibrium social security contribution rates is also taken into account.<br />

To see how this negative income effect may modify these dynamics, we consider<br />

an unexpected and permanent reduction in the labor income <strong>of</strong> the adults<br />

(and <strong>of</strong> the young) that takes place at time t, wt+i a z<br />

and z t+1 > z.<br />

Pro<strong>of</strong>. See Appendix.<br />

This proposition provides an interesting insight on the future <strong>of</strong> the early<br />

retirement provisions, which complements the results obtained in the previous<br />

section.<br />

When the effects <strong>of</strong> changes in income or wealth on the retirement<br />

behavior are taken into account, a reduction in the adult labor income induces<br />

individuals to postpone retirement, although we are not able to evaluate the<br />

impact on the equilibrium social security contributions. We argue that — to the<br />

extent that this reduction in the adults’ labor income may proxy for a drop<br />

in the life-time labor income — this may prove a crucial result<br />

to understand<br />

the future evolution <strong>of</strong> the early retirement provision. Societies characterized<br />

<strong>by</strong> economic stagnation or raise in inequalitythatincreasetheshare<strong>of</strong>low-<br />

19

income individuals may thus be associated with a less pervasive use <strong>of</strong> these<br />

early retirement provisions.<br />

4 Conclusions<br />

Since the recent studies <strong>by</strong> Blondal and Scarpetta (1998) and Gruber and Wise<br />

(1999 and 2003), among others, providing evidence that individual retirement<br />

decisions are strongly affected <strong>by</strong> the design <strong>of</strong> the social security system, measures<br />

to postpone the effective retirement age has become a milestone in all<br />

social security reform’s proposals.<br />

We concentrate on the current and future role <strong>of</strong> retirement, <strong>by</strong> analyzing the<br />

individual retirement decisions under different perspectives. First, we analyse<br />

the relation between the use <strong>of</strong> the early retirement provisions and the social<br />

security expenditure. In a cross-country sample, we find that the level <strong>of</strong> pension<br />

expenditures depends positively and significantly on the proportion <strong>of</strong> elderly<br />

in the population (demographic variable) and on measures <strong>of</strong> early retirement<br />

(retirement variables). This total effect can be decomposed in the effect on the<br />

number <strong>of</strong> pensioners as proportion <strong>of</strong> total population and the effect on the<br />

per capita average pension. An older population and/or more early retirement<br />

imply more pensioners, while it has hardly any effect on the generosity <strong>of</strong> the<br />

system, i.e., on the per capita average pension.<br />

We then introduce a political economy theoretical model to analyse the long<br />

term determinants <strong>of</strong> early retirement and the evolution <strong>of</strong> the social security<br />

system and <strong>of</strong> the early retirement provisions. In our politico-economic Markovian<br />

environment, every period an adult median voter determines the social<br />

security contribution <strong>by</strong> considering the evolution <strong>of</strong> the early retirement behavior.<br />

We use two specifications <strong>of</strong> our economic environment. In the former model,<br />

20

we emphaze the relevance <strong>of</strong> the incentives to retire early — i.e., the substitution<br />

effect — in line with a large empirical literature which shows how (at the margin)<br />

non-actuarially fair pension systems may induce rational agents to retire<br />

early, <strong>by</strong> reducing the opportunity cost <strong>of</strong> leisure. In this scenario, we obtain<br />

a political equilibrium characterized <strong>by</strong> a raising sequence <strong>of</strong> social security tax<br />

rates converging to a steady state. Along this equilibrium path, the use <strong>of</strong> early<br />

retirement provisions is increasing. <strong>The</strong> results <strong>of</strong> the comparative statics on<br />

this specification are dismaying. In line with the conventional wisdom in the<br />

economic literature, but unlike most <strong>of</strong> the implications found in the political<br />

economy literature (see Galasso and Pr<strong>of</strong>eta, 2002), productivity slow-downs<br />

(and aging) are expected to lead to higher social security contributions and to<br />

more early retirement.<br />

In the latter economic specification, we introduce a negative effect <strong>of</strong> income<br />

on the retirement decisions: a decrease in the labor income when adult leads to<br />

postpone retirement. In this scenario, which aims at including an additional long<br />

term determinant <strong>of</strong> the retirement decision — namely the life-time income — the<br />

political economic equilibrium is still characterized <strong>by</strong> an increasing sequence<br />

<strong>of</strong> social security tax rates and early retirement converging to a steady state.<br />

Yet, comparative statics now suggest that a decrease in the adult labor income<br />

will reduce the use <strong>of</strong> early retirement provisions, even after the effects on the<br />

equilibrium social security contributions are considered. To the extent that this<br />

change in adult income may proxy for a change in the net life-time income,<br />

we believe that this may prove an important result for the evolution <strong>of</strong> the<br />

early retirement provisions. In fact, we notice that, <strong>by</strong> reducing the internal<br />

rate <strong>of</strong> return to social security, aging also decreases the life-time net income <strong>of</strong><br />

the new generations — the more so, the more the system is used. In its initial<br />

specification — with no income effects — our politico-economic model suggests<br />

that aging leads to a large social security system and to more early retirement.<br />

21

Yet, to the extent that this also translates into a lower life-time income, an<br />

additional channel may arise that reduces the use <strong>of</strong> early retirement provisions<br />

and hence postpones retirement.<br />

References<br />

[1] Azariadis, C. and Galasso, V., 2002. “Fiscal Constitutions”. Journal <strong>of</strong><br />

Economic <strong>The</strong>ory 103, 255-281.<br />

[2] Bassetto, M. , 1999. “Political Economy <strong>of</strong> Taxation in an Overlapping-<br />

Generations Economy”, Federal Reserve Bank <strong>of</strong> Minneapolis Discussion<br />

Paper, no. 133<br />

[3] Boskin, M. 1977. “Social Security and <strong>Retirement</strong> Decisions.” Economic<br />

Inquiry, Vol. 15 (1), 1-25.<br />

[4] Boskin and Hurd, 1978. “<strong>The</strong> effect <strong>of</strong> social security on early retirement”.<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Public Economics, 10, 361-377.<br />

[5] Blondal S. and S. Scarpetta, 1998. “Falling Participation Rates Among<br />

OlderWorkersinOECDCountries:theRole<strong>of</strong>SocialSecuritySystems”,<br />

OECD Economic Department Working Paper.<br />

[6] Casamatta, G., H. Cremer and P. Pestieau, 2002. “Voting on Pensions with<br />

Endogenous <strong>Retirement</strong> Age”, mimeo.<br />

[7] Costa, D.L., 1998, “<strong>The</strong> <strong>Evolution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Retirement</strong>: An American Economic<br />

History 1880-1990”, University <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press.<br />

[8] <strong>Conde</strong>-Ruiz J.I. and V. Galasso, 2003. “Early <strong>Retirement</strong>”, Review <strong>of</strong> Economic<br />

Dynamics, 6, 12-36.<br />

[9] <strong>Conde</strong>-Ruiz J.I. and V. Galasso, 2004, “<strong>The</strong> Macroeconomics <strong>of</strong> Early <strong>Retirement</strong>”,<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Public Economics 88 (9-10):1849-1969.<br />

22

[10] Costa, D. (1998). “<strong>The</strong> <strong>Evolution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Retirement</strong>”. Chicago: University <strong>of</strong><br />

Chicago Press.<br />

[11] Crawford V.P. and D. Lilien, 1981. “Social Security and retirement decision”,<br />

Quarterly Journal <strong>of</strong> Economics, 95, 505-529.<br />

[12] Cremer, H. and Pestieau, P., 2003, “<strong>The</strong> Double Dividend <strong>of</strong> Postponing<br />

<strong>Retirement</strong>”, International Tax and Public Finance 10, 419-434.<br />

[13] Cremer, H., J. Lozachemeur and P. Pestieau, 2002, “Social Security, <strong>Retirement</strong><br />

Age and Optimal Income Taxation”. mimeo<br />

[14] Cremer, H., and P. Pestieau, 2000, “Reforming Our Pension System: Is<br />

it a Demographic, Financial or Political Problem?”, European Economic<br />

Review, 40, 974-983.<br />

[15] Diamond P. and J. Housman, 1984 “<strong>The</strong> retirement and Unemployment<br />

Behavior <strong>of</strong> older men” in Aaron, H. and Burtless, G (eds). <strong>Retirement</strong> and<br />

economic behaviour (Washington, D.C. Brookings Institution), 97-134.<br />

[16] Diamond, P. A. and J. A. Mirrless “A model <strong>of</strong> social Insurance and with<br />

variable retirement”, Journal <strong>of</strong> Public Economics 10, 294-336<br />

[17] Fenge R. and Pestieau, P.,“Social security and retirement” MIT Press<br />

forthcoming<br />

[18] Feldstein, M., 1974. “Social Security, induced retirement, and Aggregate<br />

Capital Accumulation”, Journal <strong>of</strong> Political Economy, 82(5), 905-926.<br />

[19] Forni, L., 2005 “Social security as Markov equilibrium in OLG Models”<br />

Review <strong>of</strong> Economic Dynamics 1, 178-194.<br />

[20] Galasso, V., and P. Pr<strong>of</strong>eta, 2002, “<strong>The</strong> Political Economy <strong>of</strong> Social Security:<br />

A Survey”, European Journal <strong>of</strong> Political Economy, 18, 1-29.<br />

23

[21] Gonzalez-Eiras, M. and D. Niepelt, 2004. “Sustaining Social Security”. WP<br />

371, IIES Stockholm.<br />

[22] Grossman, G. and Helpman, E. 1998. “Intergenerational redistribution with<br />

short-lived governments” 108: 1299-1329.<br />

[23] Gruber, J. and D. Wise (eds.), 1999. “Social Security and <strong>Retirement</strong><br />

Around the World”, University <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press, Chicago.<br />

[24] Gruber, J. and D. Wise (eds.), 2004, “Social Security Programs and <strong>Retirement</strong><br />

Around the World: Micro Estimation”, University <strong>of</strong> Chicago Press.<br />

[25] Hassler, J. Rodriguez-Mora, J.V., Storesletten, K. and Zilibotti, F., 2003,<br />

“<strong>The</strong> Survival <strong>of</strong> the Welfare State”, American Economic Review 93(1),<br />

87-112.<br />

[26] Hu, S., 1979. “Social security, the supply <strong>of</strong> labor and capital accumulation”,<br />

American Economic Review 69 (3), 274-283.<br />

[27] Hurd, M. and Boskin, M.J., 1984. “<strong>The</strong> Effect <strong>of</strong> Social Security on <strong>Retirement</strong><br />

in the Early 1970s.” Quarterly Journal <strong>of</strong> Economics, 99, 767-790.<br />

[28] International Labour Office, 1985-2000. Yearbook <strong>of</strong> Labour Statistics.<br />

[29] International Labour Office, 2000. World Labour Report 2000.<br />

[30] International Monetary Fund, Government Finance Statistics Yearbook<br />

(1985-1998).<br />

[31] Jensen, S., Lau, M. and Poutvaara, P., 2004, “Efficiency and Equity Aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> Alternative Social Security Rules”, Finanzarchiv<br />

[32] Jimeno, J. F., 2002a. “Demografía, empleo, salarios y pensiones”, Documento<br />

de Trabajo 2002-04. FEDEA, Madrid.<br />

24

[33] Jimeno, J. F., 2002b, “Incentivos y desigualdad en el sistema español de<br />

pensiones contributivas de jubilación”. Documento de Trabajo 2002-13.<br />

FEDEA, Madrid.<br />

[34] Krusell, P. Quadrini, V. and Ríos-Rull, 1997, J.V. “Politico-Economic Equilibrium<br />

and Economic Growth” Journal <strong>of</strong> Economic Dynamics and Control,<br />

21:1.<br />

[35] Lacomba, J.A: and F.M. Lagos, 2000, “Election on <strong>Retirement</strong> age”,<br />

mimeo.<br />

[36] Latulippe, D., 1997. “Effective <strong>Retirement</strong> Age and Duration <strong>of</strong> <strong>Retirement</strong><br />

in the Industrialised Countries Between 1950 and 1990”. ILO Discussion<br />

Paper 2.<br />

[37] Michel, P. and Pestieau, P., 1999. “Social security and early retirement in<br />

an overlapping-generations growth model”, CORE Discussion Paper 9951.<br />

[38] Pr<strong>of</strong>eta, P., 2002. “Aging and <strong>Retirement</strong>: Evidence Across Countries”,<br />

International Tax and Public Finance 9, 651-672.<br />

[39] United Nations, Demographic Yearbook (1990-2000).<br />

25

5 Appendix<br />

5.1 Pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> proposition 2<br />

<strong>The</strong> first order condition <strong>of</strong> the median voter is:<br />

−z t w a t (1 + r)+ ∂p t+1<br />

∂τ t+1<br />

Q 0 (z t ) Z 0 (τ t )=0<br />

where<br />

∂p t+1<br />

=(1+n t )(1− 2τ t+1 ) w t+1 and Z 0 (τ t )=−1<br />

∂τ t+1<br />

Thus, the first order condition becomes<br />

−z t w a t (1 + r) − (1 + n t ) w t+1 Q 0 (z t )+2(1+n t ) w t+1 Q 0 (z t ) Q (z t )=0<br />

Integrating the above equation with respect to z t ,weobtain<br />

A − z 2 t w a t (1 + r) − 2(1+n t ) w t+1 Q +2(1+n t ) w t+1 Q 2 =0<br />

where A is a constant <strong>of</strong> integration. Solving the equation w.r.t. Q, wehave<br />

s<br />

Q (τ t )= 1 2 ∓ 1 1 − 2A − 2(1 + r)wa t (1 − τ t ) 2<br />

.<br />

2<br />

(1 + n t )w t+1<br />

Since τ t+1 = Q (τ t ) represents a tax rate, it has to be that Q ∈ [0, 1]. Thus, we<br />

have that<br />

τ t+1 = Q (τ t )= 1 2 − 1 2<br />

s<br />

1 − 2A − 2(1 + r)wa t (1 − τ t ) 2<br />

(1 + n t ) w t+1<br />

and the following restrictions on the free parameter A:<br />

(1 + r)w a t (1 − τ t ) 2 ≤ A ≤ (1 + n t) w t+1<br />

2<br />

+(1+r)w a t (1 − τ t ) 2 .<br />

Notice that, since the lower constraint is maximized for τ t+1 = 0, while the<br />

upper constraint is minimized for for τ t+1 =1,asufficient condition for Q ∈<br />

[0, 1] is<br />

A ∈ [(1 + r)wt a , (1 + n t) w t+1<br />

].<br />

2<br />

26

Finally, to make sure that the upper bound is indeed larger that the lower<br />

bound, we need to assume that (1 + n t ) w t+1 > 2(1 + r)wt a ; or, analogously,<br />

that [(1 + n t−1 ) ϕ +1]/2 > (1 + r) / [(1 + n t )(1+g)]. Q.E.D.<br />

5.2 Pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> proposition 3<br />

Consider the economy at its steady state and recall that eq. 10 provides the law<br />

<strong>of</strong> motion <strong>of</strong> the social security contribution rate. At time t + 1, a decrease in<br />

the population growth rate, n t+1 τ t ,and<br />

— from eq. 4 — so does the early retirement, since z t+1 =1− τ t+1

w a t+1 =(1+g) w a t . By setting τ t+1 = τ t = τ in eq. 10 we obtain the following<br />

value for the steady state social security contribution rate:<br />

τ =<br />

(1 + n)(1+g) w − (1 + r)wa<br />

2(1 + n)(1+g) w − (1 + r) w a + (16)<br />

q<br />

(1 + n) 2 (1 + g) 2 w 2 − A [2(1 + n)(1+g) w − (1 + r) w a ]<br />

−<br />

2(1 + n)(1+g) w − (1 + r) w a (17)<br />

Simple algebra shows that τ ∈ [0, 1/2) and that ∂τ/∂n < 0. Hence, aging<br />

increases the social security contribution rate at steady state and — <strong>by</strong> eq. 4—<br />

early retirement. Q.E.D.<br />

5.3 Pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> proposition 4<br />

Consider the steady state social security contribution rate at eq. 16. Simple<br />

algebra shows that ∂τ/∂g < 0. Hence, productivity slow-downs increase the<br />

social security contribution rate at steady state and — <strong>by</strong> eq. 4— early retirement.<br />

Q.E.D.<br />

5.4 Pro<strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> proposition 5<br />

At time t, when the adults’ and young’s labor income drops, the median voter<br />

will not change the social security contribution rate from its steady state level,<br />

in order to validate the expectations <strong>of</strong> the previous median voter at time t − 1.<br />

She will however expect the tax rate to be changed at t + 1 due to this drop in<br />

labor income. By eq. 12, it is thus immediate to see that z t =1− τ − δwt a > z<br />

=1− τ − δwt−1, a sincewt a

∂τ t+1<br />

∂w = − δ<br />

(1 + n t+1 ) ϕ +1 + Θ<br />

s µ<br />

1 − δ(wa t+1) 2<br />

2<br />

w t+1<br />

2<br />

− 2[A−(1+r)wa t (1−τ t−δw a t )2 ]<br />

(1+n t )w t+1<br />

where<br />

Θ =<br />

Ã<br />

δ<br />

1 − δ ¡ wt+1<br />

a<br />

(1 + n t+1 ) ϕ +1<br />

¢ 2<br />

!<br />

w t+1<br />

− [(1 + n t+1) ϕ +1] £ A − (1 + r)w a t z t<br />

2 ¤<br />

(1 + n t )(w t+1 ) 2<br />

− (1 + r)z t(z t − 2δw a t )<br />

(1 + n t )w t+1<br />

Notice that we cannot sign ∂τ t+1 /∂w; however, it is easy to show that a sufficient<br />

µ<br />

condition for Θ > 0isthatA w t+1 .<br />

By eq. 12, we thus have that<br />

∂z t+1<br />

∂w<br />

δ<br />

=<br />

(1 + n t+1 ) ϕ +1 − Θ<br />

2(1+n t+1 )(w t+1 ) 2 − δ =<br />

(1 + n t+1 ) ϕ<br />

= −δ<br />

(1 + n t+1 ) ϕ +1 − Θ<br />

2(1+n t+1 )(w t+1 ) 2 < 0<br />

since Θ > 0. Q.E.D.<br />

29

Table 1. <strong>The</strong> variables (basic statistics)<br />

Variable Obs Mean STD Error Min Max<br />

OLD population over 65 years old/total population 106 8.487 4.935 2 18.2<br />

ACTOT activity rate <strong>of</strong> individuals 55-64 110 0.488 0.139 0.19 0.87<br />

ACM activity rate <strong>of</strong> man 55-64 110 0.69 0.159 0.29 0.93<br />

AC1TOT activity rate <strong>of</strong> individuals 40-55 110 0.747 0.106 0.48 0.93<br />

AC1M activity rate <strong>of</strong> man 40-55 110 0.921 0.074 0.35 1<br />

DAC= AC1TOT-ACTOT 110 0.258 0.154 0 0.62<br />

DACM=AC1M-ACM 110 0.231 0.16 0 0.55<br />

PENSEXP Pension Expenditures as % <strong>of</strong> GDP 84 4.917 4.125 0 14.26<br />

NUMPENS %<strong>of</strong> pensioners/ total population 53 10.503 10.41 0.01 29.7<br />

AVPENS per capita average pension 50 1.049 1.94 0 11<br />

GDP per capita GDP (U.S. $) 101 10850.12 9305.93 6 42769<br />

Table 2. Determinants <strong>of</strong> pension expenditures (All countries)<br />

Independent variables Dependent variable<br />

PENSEXP (a) PENSEXP (b) PENSEXP (c)<br />

CONSTANT 2.05 (0,91) -2.28 (0.42) -2.42 (0.42)<br />

ACTOT -6.8(1.45)***<br />

DAC 6.51 (1.77)***<br />

DACM 6.57 (1.55)***<br />

OLD 0.6 (0.05)*** 0.51 (0.07)*** 0.56 (0.057)***<br />

GDP 0.00005 (0.00002)** 0.00006 (0.00002)** 0.00004 (0.00002)**<br />

N. Obs 84 84 84<br />

R**2 0.837 0.823 0.83<br />

** significant at 5%, *** significant at 1%<br />

Table 3. Determinants <strong>of</strong> pension expenditures (OECD countries)<br />

Independent variables Dependent variable<br />

PENSEXP (a) PENSEXP (b) PENSEXP (c)<br />

CONSTANT 0.39 (2.36) -7.34 (2.02) -6.9 (1.69)<br />

ACTOT -10.49 (2.51)***<br />

DAC 11.33 (3.42)***<br />

DACM 12.26 (2.54)***<br />

OLD 0.76 (0.12)*** 0.7 (0.13)*** 0.69 (0.11)***<br />

GDP 0.0001 (0.00004)** 0.0001 (0.00005)* 0.00008 (0.00004)**<br />

N. Obs 26 26 26<br />

R**2 0.79 0.76 0.82<br />

** significant at 5%, ** *significant at 1%

Table 4. Number <strong>of</strong> pensioners<br />

INDEPENDENT VARIABLES DEPENDENT VARIABLE<br />

NUMPENS (a)<br />

NUMPENS (b)<br />

CONSTANT 4.53 (3.54) -8.72 (1.21)<br />

OLD 1.84 (0.14)*** 1.46 (0.17)***<br />

ACTOT -20.65 (5.95)***<br />

DAC 24.25 (5.13)***<br />

N. Obs 53 53<br />

R**2 0.84 0.87<br />

** *significant at 1%<br />

Table 5. Average pension<br />

INDEPENDENT<br />

VARIABLES<br />

AVPENS<br />

CONSTANT 2.31 (0.62)***<br />

DAC -0.34 (2.52) 1<br />

OLD -0.13 (0.086) 1<br />

N. Obs. 50<br />

R**2 0.1<br />

** *significant at 1% , 1 not significant

τ t+1<br />

Q(τ t<br />

)<br />

τ ss<br />

Figure 1<br />

τ ss<br />

τ t

RELACION DE DOCUMENTOS DE FEDEA<br />

DOCUMENTOS DE TRABAJO<br />

2005-03: “<strong>The</strong> <strong>Evolution</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Retirement</strong>”, J. <strong>Ignacio</strong> <strong>Conde</strong>-Ruiz., <strong>Vincenzo</strong> Galasso y Paola<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>eta.<br />

2005-02: “Housing deprivation and health status: Evidence from Spain” Luis Ayala, José M.<br />

Labeaga y Carolina Navarro.<br />

2005-01: “¿Qué determina el éxito en unas Oposiciones?”, Manuel F. Bagüés.<br />

2004-29: “Demografía y empleo de los trabajadores próximos a la jubilación en Cataluña”, J. <strong>Ignacio</strong><br />

<strong>Conde</strong>-Ruiz y Emma García<br />

2004-28: “<strong>The</strong> border effect in Spain”, Salvador Gil-Pareja, Rafael Llorca-Vivero, José A.<br />

Martínez-Serrano y Josep Oliver-Alonso.<br />

2004-27: “Economic Consequences <strong>of</strong> Widowhood in Europe: Cross-country and Gender Differences”<br />

Namkee Ahn.<br />

2004-26: “Cross-skill Redistribution and the Trade<strong>of</strong>f between Unemployment Benefits and<br />

Employment Protection”, Tito Boeri, J. <strong>Ignacio</strong> <strong>Conde</strong>-Ruiz y <strong>Vincenzo</strong> Galasso.<br />

2004-25: “La Antigüedad en el Empleo y los Efectos del Ciclo Económico en los Salarios. El Caso<br />

Argentino”, Ana Carolina Ortega Masagué.<br />

2004-24: “Economic Inequality in Spain: <strong>The</strong> European Union Household Panel Dataset”, Santiago<br />

Budría y Javier Díaz-Giménez.<br />

2004-23: “Linkages in international stock markets: Evidence from a classification procedure”, Simon<br />

Sosvilla-Rivero y Pedro N. Rodríguez.<br />

2004-22: “Structural Breaks in Volatility: Evidence from the OECD Real Exchange Rates”, Amalia<br />

Morales-Zumaquero y Simon Sosvilla-Rivero.<br />

2004-21: “Endogenous Growth, Capital Utilization and Depreciation”, J. Aznar-Márquez y J. R.<br />

Ruiz-Tamarit.<br />

2004-20: “La política de cohesión europea y la economía española. Evaluación y prospectiva”, Simón<br />

Sosvilla-Rivero y José A. Herce.<br />

2004-19: “Social interactions and the contemporaneous determinants <strong>of</strong> individuals’ weight”, Joan<br />

Costa-Font y Joan Gil.<br />

2004-18: “Demographic change, immigration, and the labour market: A European perspective”, Juan<br />

F. Jimeno.<br />

2004-17: “<strong>The</strong> Effect <strong>of</strong> Immigration on the Employment Opportunities <strong>of</strong> Native-Born Workers:<br />

Some Evidence for Spain”, Raquel Carrasco, Juan F. Jimeno y Ana Carolina Ortega.<br />

2004-16: “Job Satisfaction in Europe”, Namkee Ahn y Juan Ramón García.<br />

2004-15: “Non-Catastrophic Endogenous Growth and the Environmental Kuznets Curve”, J. Aznar-<br />

Márquez y J. R. Ruiz-Tamarit.<br />

2004-14: “Proyecciones del sistema educativo español ante el boom inmigratorio”, Javier Alonso y<br />

Simón Sosvilla-Rivero.<br />

2004-13: “Millian Efficiency with Endogenous Fertility”, J. <strong>Ignacio</strong> <strong>Conde</strong>-Ruiz, Eduardo L.<br />

Giménez y Mikel Pérez-Nievas.<br />

2004-12: “Inflation in open economies with complete markets”, Marco Celentani, J. <strong>Ignacio</strong> <strong>Conde</strong><br />

Ruiz y Klaus Desmet.<br />

TEXTOS EXPRESS<br />

2004-02: “¿Cuán diferentes son las economías europea y americana?”, José A. Herce.<br />

2004-01: “<strong>The</strong> Spanish economy through the recent slowdown. Current situation and issues for the<br />

immediate future”, José A. Herce y Juan F. Jimeno.