Network 12-1.pdf - Canadian Women's Health Network

Network 12-1.pdf - Canadian Women's Health Network

Network 12-1.pdf - Canadian Women's Health Network

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

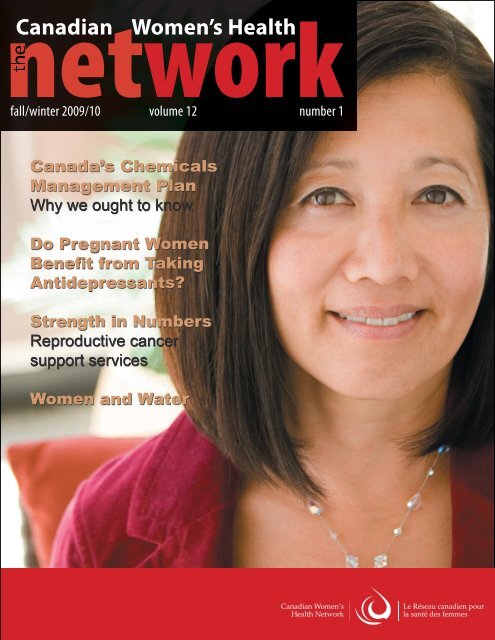

network<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong><br />

the<br />

Women’s <strong>Health</strong><br />

fall/winter 2009/10 volume <strong>12</strong> number 1<br />

Canada’s Chemicals<br />

Management Plan<br />

Why we ought to know<br />

Do Pregnant Women<br />

Benefit from Taking<br />

Antidepressants?<br />

Strength in Numbers<br />

Reproductive cancer<br />

support services<br />

Women and Water<br />

CANADIAN WOMEN’S HEALTH NETWORK FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 1

e d i t o r ’ s n o t e<br />

I’m pleased to write to you for the first time as the new Editor of<br />

<strong>Network</strong> magazine and Director of Communications at the <strong>Canadian</strong><br />

Women‘s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Network</strong>. It is exciting to take the helm of such a<br />

vibrant publication, and as we move forward I hope to continue to<br />

provide you with the best information and news on women’s health you<br />

have come to expect from <strong>Network</strong>.<br />

In this issue, profiles of work by the Centres of Excellence for<br />

Women’s <strong>Health</strong> gives readers a look at some of the latest projects on<br />

women’s health in Canada. In a piece by the CWHN’s new Director<br />

of Knowledge Exchange, Jane Shulman, we examine work from the<br />

Atlantic Centre of Excellence in Women’s <strong>Health</strong> on the support services<br />

available for women with reproductive cancers, and how they might<br />

expand by teaming up with existing breast cancer support networks.<br />

The experiences of young Aboriginal mothers are given a<br />

powerful voice in a report from the Prairie Women’s <strong>Health</strong> Centre of<br />

Excellence. In “Young Aboriginal Mothers in Winnipeg,” the firsthand<br />

accounts as well as the trends and statistics of motherhood in the city<br />

show the gaps in education and support.<br />

Based in Ontario, the National <strong>Network</strong> on the Environment and<br />

Women’s <strong>Health</strong> brings to light the way the chemicals in <strong>Canadian</strong>s’ lives<br />

are regulated with an article on Canada’a new Chemical Management<br />

Plan. Authors Dolon Chakavartty and Anne Rochon Ford break down<br />

<strong>Health</strong> Canada and Environment Canada’s plan to reexamine the safety of<br />

200 chemicals, and tell the public how they can learn more and voice their<br />

opinions. In “Women and Water,” NNEWH’s new online home for research<br />

on the relationship between women and water in Canada is examined.<br />

In research originally done for Women and <strong>Health</strong> Protection,<br />

Dr. Barbara Mintzes examines antidepressants, pregnancy, and what<br />

the evidence is for their use. Do they help, harm, or neither? In “Do<br />

The opinions expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily<br />

represent the views of the <strong>Canadian</strong> Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Network</strong>, its funders or<br />

its members. Arcles are intended to provide helpful informaon and are not<br />

meant to replace the advice of your personal health praconer.<br />

The <strong>Canadian</strong> Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Network</strong> gratefully acknowledges the funding<br />

support provided by the Women’s <strong>Health</strong> Contribuon Program of the Bureau<br />

of Women’s <strong>Health</strong> and Gender Analysis, <strong>Health</strong> Canada, as well as the<br />

support and donaons of the individuals and groups whose work strengthens<br />

the <strong>Network</strong>.<br />

network / le reséau<br />

volume <strong>12</strong> number 1 fall/winter 2009/10<br />

Editor: Signy Gerrard<br />

Translaon: Intersigne<br />

Subscripons: Léonie Lafontaine<br />

Advisory Commiee: Abby Lippman,<br />

Anne Rochon Ford, Martha Muzychka,<br />

Susan White and Madeline Boscoe<br />

<strong>Network</strong>/Le Réseau is published in<br />

English and French twice a year by the<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

(CWHN). Parts of <strong>Network</strong>/Le Réseau<br />

are also available on the CWHN website:<br />

www.cwhn.ca<br />

To subscribe to <strong>Network</strong> magazine, call<br />

1-888-818-9172 or email cwhn@cwhn.<br />

ca for details and payment opons.<br />

Individuals receive two issues of <strong>Network</strong><br />

for $15, four issues for only $25.<br />

Organizaons – two issues for $35. Back<br />

issues are also available at $5 each. We<br />

welcome your ideas, contribuons and<br />

leers. All requests for informaon and<br />

resources, as well as correspondence related<br />

to subscripons and undeliverable<br />

copies, should be sent to the address<br />

below.<br />

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40036219<br />

RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO<br />

<strong>Network</strong>/Le Réseau<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Network</strong><br />

203-419 Graham Avenue<br />

Winnipeg MB CANADA R3C 0M3<br />

Tel: (204) 942-5500<br />

Fax: (204) 989-2355<br />

Toll-Free: 1-888-818-9172<br />

TTY (toll-free): 1-866-694-6367<br />

Email: cwhn@cwhn.ca<br />

Website: www.cwhn.ca<br />

CWHN Staff<br />

Execuve Director: Madeline Boscoe<br />

Assistant Execuve Director: Susan White<br />

Director of Communicaons:<br />

Signy Gerrard<br />

Director of Knowledge Exchange:<br />

Jane Shulman<br />

Technical Support: Polina Rozanov<br />

Administrave Services Coordinator:<br />

Léonie Lafontaine<br />

Resource Clerk: Tanya Smith<br />

Finance Officer: Janice Nagazine<br />

Bookkeeper: Rhonda Thompson<br />

2 FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 NETWORK

pregnant women benefit from taking antidepressants?,” interesting questions are raised about what we know and<br />

what we assume about the benefits of one of Canada’s most frequently prescribed drugs.<br />

Finally, see an introduction to the CWHN’s latest online expansions - our new webinar series. Launched<br />

in the fall, these hour-long web broadcasts have already brought hundreds of participants new and important<br />

information on women’s health topics, from drug regulation in Canada to more from Dr. Mintzes on the risks and<br />

benefits of antidepressants in pregnancy. Look for upcoming webinars on the CWHN website and in the Brigit’s<br />

Notes newsletter as the year goes on!<br />

Sincerely,<br />

Signy Gerrard<br />

Director of Communications<br />

Support a national voice for women’s health!<br />

CWHN thanks all of our donors, who make such an important contribution to our work.<br />

If you would like to contribute, please go to our website www.cwhn.ca and click on “donate”<br />

or call CWHN at 1-888-818-9172 (toll free).<br />

WHAT’S INSIDE<br />

4 Aboriginal mothers in Winnipeg:<br />

Research looks at attitudes and<br />

understanding around sex and<br />

motherhood<br />

6 Canada’s Chemical<br />

Management Plan:<br />

Why we ought to know<br />

9 The comprehensive feminist<br />

approach to health<br />

11 Do pregnant women benefit<br />

from taking antidepressants?<br />

14 CWHN launches a new<br />

webinar series<br />

15 Strength in numbers:<br />

Project plans to unite support<br />

services for women with<br />

breast and reproductive cancers<br />

16 Women and water<br />

19 What we’re reading:<br />

Recommended resources<br />

from our library<br />

CANADIAN WOMEN’S HEALTH NETWORK FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 3

A M <br />

Research looks at atudes and unders<br />

By Jane Shulman<br />

Aboriginal teenagers are four<br />

times more likely than non-<br />

Aboriginal teens to have<br />

babies. According to data cited in<br />

the report Young Aboriginal Mothers<br />

in Winnipeg, published in May<br />

2009 by the Prairie Women’s <strong>Health</strong><br />

Centre of Excellence (PWHCE),<br />

more than one in five First Nations<br />

babies were born to mothers aged<br />

15 to 19 years in 1999.<br />

By comparison, the <strong>Canadian</strong><br />

ratio was one in 20. Aside from<br />

the economic hardships that many<br />

young mothers face, there are increased<br />

health risks for babies born<br />

to teens. Researchers contend that<br />

there are socio-cultural issues at<br />

play that have not been thoroughly<br />

investigated.<br />

In order to uncover the issues<br />

that feed this trend, PWHCE<br />

researcher Lisa Murdock conducted<br />

interviews and group sessions with<br />

28 women living in Winnipeg,<br />

mostly between the ages of 18 and<br />

27 years old. She ventured to find<br />

out why girls from First Nations,<br />

Métis and Inuit populations<br />

are more likely<br />

than non-Aboriginals<br />

to become mothers at<br />

a young age, and support<br />

young mothers by<br />

asking women to tell<br />

her in their own words<br />

about their experiences.<br />

Themes included<br />

the women’s knowledge<br />

of sex before they<br />

became pregnant, their<br />

feelings about intimacy,<br />

where they learned<br />

about pregnancy and<br />

STIs (if they did), the support they<br />

received while pregnant and the<br />

challenges of young parenthood.<br />

You can’t<br />

just stop<br />

and tell<br />

kids they<br />

can’t get<br />

pregnant<br />

at a young<br />

age.<br />

There was significant focus on the<br />

kinds of programs that women<br />

would have accessed had they been<br />

available, and recommendations for<br />

future programming.<br />

Compelling in<br />

Murdock’s report<br />

is the first-person<br />

reporting from the<br />

women she interviewed,<br />

which illuminates<br />

the issues. The<br />

women in the project<br />

had lived experiences<br />

to share and insight<br />

that went beyond the<br />

telling of personal narratives.<br />

Murdock quotes an<br />

interviewee discussing<br />

teen pregnancy within<br />

the context of the oppression of<br />

Aboriginal peoples, and the breakdown<br />

of their family structure.<br />

4 FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 NETWORK

W<br />

tanding around sex and motherhood<br />

“I think it goes back to a lot of<br />

different things. It goes back to dysfunctional<br />

homes, childhood sexual<br />

abuse, alcoholism, everything. It just<br />

comes down to it. When you get<br />

such abuse, a high percentage of the<br />

time you end up working the streets<br />

or you end up sleeping around, you<br />

end up having kids at young ages<br />

… You can’t just stop and tell kids<br />

they can’t get pregnant at a young<br />

age. It’s not good. You gotta work<br />

on the things that happened to them<br />

too … What’s making them become<br />

like that? It doesn’t mean all<br />

people are being sexually abused,<br />

but a high percentage of the people<br />

live in dysfunctional homes, and<br />

just want to feel loved and decide<br />

to have a baby at a young age. It<br />

becomes then, part of the system.”<br />

Murdock notes that women<br />

mentioned the differences between<br />

Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal<br />

beliefs around abortion and adoption<br />

as another reason for the high<br />

rates of teen pregnancy among<br />

Aboriginal women. Says another<br />

interviewee:<br />

“There’s a lot of girls out there<br />

who just want a baby. Even so<br />

young, they want to have a baby so<br />

they can have something to love, for<br />

someone to love them.”<br />

While the women interviewed<br />

said they were happy with the<br />

children they had, most said they<br />

thought young teens were not<br />

equipped to be having babies. They<br />

suggested prevention strategies<br />

including sex education starting in<br />

elementary school, presentations<br />

in high schools from young parents<br />

talking about their challenges, and<br />

better support programs for young<br />

parents. They stress that communication<br />

within families and between<br />

girls and people in their communi-<br />

ties is the key to prevention.<br />

“I’d say prevention first. Like,<br />

the whole talking to the guardian,<br />

like the parents and the guardian<br />

thing. Like teaching them how to<br />

talk to their kids, that’d be good.<br />

And a class how to talk to your<br />

parents might even help too because<br />

kids are really cocky these<br />

days. They’re trying to be independent,<br />

but that’s not the case. I think<br />

that would help. A class on how to<br />

connect with each other would be<br />

good.”<br />

The report, Young Aboriginal<br />

Mothers in Winnipeg, is available on<br />

the Prairie Women’s <strong>Health</strong> Centre<br />

of Excellence website at www.<br />

pwhce.ca/youngAborigMothers-<br />

Murdock.htm<br />

Jane Shulman is the Director of<br />

Knowledge Exchange at the <strong>Canadian</strong><br />

Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Network</strong>.<br />

CANADIAN WOMEN’S HEALTH NETWORK FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 5

CANADA’S<br />

CHEMICALS<br />

MANAGEMENT<br />

PLAN<br />

Why<br />

we<br />

ought<br />

to<br />

know<br />

By Anne Rochon Ford and Dolon Charkavartty<br />

ONE WOULD EXPECT THAT THE THOUSANDS OF CHEMICALS IN DAILY USE – IN OUR<br />

HOMES, IN INDUSTRY, AND ELSEWHERE – HAVE BEEN THROUGH A FORMAL REVIEW<br />

PROCESS BY OUR GOVERNMENTS TO ENSURE THAT THEY ARE SAFE FOR HUMAN EX-<br />

POSURE. IN FACT, HOWEVER, MOST CHEMICALS IN CURRENT USE HAVEN’T BEEN FULLY AS-<br />

SESSED AND CAN REALLY ONLY BE CONSIDERED “SAFE” UNTIL IT’S PROVEN OTHERWISE.<br />

Fortunately, there is a possibility that this far-fromreassuring<br />

situation may change. In December 2006,<br />

the Government of Canada announced a new process<br />

for assessing and managing the potential health and<br />

environmental risks from over 23,000 chemicals that<br />

are widely used in Canada. Included in this “Chemicals<br />

Management Plan” (CMP) is a “Challenge” to<br />

industry: unless industry provides information that<br />

suggests otherwise, 200 of these chemicals will be<br />

considered toxic (as defined by the <strong>Canadian</strong> Environmental<br />

Protection Act or CEPA). In other words, the<br />

ground has shifted – in the case of some chemicals,<br />

at least – from “safe until proven otherwise” to “toxic<br />

until proven otherwise.” Given the increasing evidence<br />

linking exposure to even trace amounts of chemicals<br />

in our air, water, soil, food, and homes with chronic<br />

illnesses including cancer, this is a step in the right<br />

direction.<br />

Over a three-year period, <strong>Health</strong> Canada and<br />

Environment Canada have been releasing the names<br />

of fifteen of the 200 chemicals in question every three<br />

months. These chemicals will be re-evaluated based<br />

on four factors, namely persistence, bioaccumulation,<br />

inherent toxicity, and greatest potential for exposure.<br />

This re-evaluation is currently underway and<br />

individuals and groups in the general public – not<br />

just scientists and industry – are being encouraged to<br />

become knowledgeable about what is going on and<br />

to get involved. Funding was provided to the <strong>Canadian</strong><br />

Environmental <strong>Network</strong> / Réseau canadien<br />

de l’environnement (RCEN), in collaboration with<br />

the environmental NGO, Environmental Defence,<br />

6 FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 NETWORK

to coordinate a process of civil<br />

society engagement. When the<br />

names of chemicals are released,<br />

the RCEN notifies a network of<br />

individuals and groups about them<br />

and explains what the government<br />

has concluded (based on existing<br />

research). The RCEN then<br />

provides its own “plain language”<br />

assessment of the literature and<br />

encourages citizen groups to learn<br />

more about these chemicals, many<br />

of which can be found in personal<br />

care products, household cleaners,<br />

cosmetics, and other products<br />

with which humans have regular<br />

contact.<br />

There will be opportunities<br />

for public input both when the<br />

quarterly releases of the names<br />

of chemicals occur (this process<br />

is now complete) and at the later<br />

stages when <strong>Health</strong> Canada and<br />

Environment Canada deliberate<br />

about how these chemicals will be<br />

“managed.”<br />

These deliberations will go on<br />

until some time in 2011.<br />

Why should women<br />

be concerned?<br />

There are both sex- (e.g.,<br />

biological) and gender-based<br />

(e.g.,social) reasons why women<br />

should be aware of these issues. In<br />

particular, women are known to<br />

have different experiences with<br />

and exposures to many of these<br />

The criteria by which chemicals are being evaluated<br />

1. Possibility for Persistence:<br />

The me it takes for a substance to break down in<br />

the environment<br />

2. Possibility for Bioaccumulaon:<br />

The tendency for a substance to accumulate in the<br />

ssues of living organisms and to travel along the<br />

food chain<br />

3. Inherent toxicity:<br />

Whether a chemical is inherently harmful to human health<br />

or to other living creatures (as disnct from<br />

the legal definion of “toxic” in CEPA)<br />

4. Represenng the Greatest Potenal for Exposure:<br />

Substances in vast amounts of use that can potenally affect<br />

large numbers of the populaon<br />

chemicals. To take the most obvious:<br />

only women get pregnant and<br />

give birth, and their exposures can<br />

affect the embryo and fetus. One<br />

particular concern is based in the<br />

substantial body of scientific literature<br />

demonstrating the unique<br />

vulnerability of the fetus to endocrine-disrupting<br />

chemicals found<br />

in daily environmental exposures<br />

to several chemical substances<br />

(e.g. pharmaceuticals in the water;<br />

Bisphenol A [BPA] found in plastic<br />

and food products; etc.).<br />

However, women’s special concerns<br />

go beyond their reproductive<br />

roles. Women and girls have other<br />

sex- and gender-based vulnerabilities<br />

to being exposed and to being<br />

harmed by the exposures that need<br />

to be considered in discussions<br />

about the control of chemicals.<br />

Sandra Steingraber’s work on the<br />

falling age of puberty provides<br />

compelling evidence to suggest<br />

that myriad factors, including<br />

exposures to endocrine-disrupting<br />

chemicals, play a role in accelerating<br />

puberty in girls.<br />

The social and caretaking roles<br />

carried out by many women,<br />

the nature of much of their paid<br />

employment in the service sector,<br />

and their greater use of personal<br />

care products (cosmetics, lotions,<br />

specialized cleansers, etc.) can<br />

all lead to daily exposure to certain<br />

chemicals, which put women<br />

at higher risk for health-related<br />

problems. Additionally, medical or<br />

health conditions that have been<br />

attributed to chemical exposures,<br />

CANADIAN WOMEN’S HEALTH NETWORK FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 7

even though these associations<br />

are often deemed controversial<br />

in the medical community (e.g.<br />

fibromyalgia, Multiple Chemical<br />

Sensitivity Syndrome), tend to be<br />

diagnosed at much higher rates in<br />

women than men.<br />

Fitting sex and gender<br />

into the Chemicals<br />

Management Plan<br />

In response to this important<br />

initiative underway at <strong>Health</strong><br />

Canada and Environment Canada,<br />

and recognizing the importance of<br />

attention to sex- and gender-based<br />

aspects of it, the National <strong>Network</strong><br />

on Environments and Women’s<br />

<strong>Health</strong> (NNEWH) has undertaken<br />

a project to foster citizen engagement<br />

among women and women’s<br />

groups in the CMP. Janelle Witzel<br />

from Environmental Defence supports<br />

this engagement. “Women’s<br />

involvement and interest in the<br />

case of BPA was instrumental in<br />

prompting government action”,<br />

she said. “There is a large potential<br />

for women’s voice and participation<br />

in the CMP process ... that<br />

could lead to policy change.”<br />

The project, which the <strong>Canadian</strong><br />

Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Network</strong> is<br />

consulting on, will involve a public<br />

forum slated for February 2010,<br />

following a web-based survey seeking<br />

input from a broad range of<br />

women across Canada. For more<br />

information on these initiatives,<br />

check the websites of NNEWH<br />

(www.nnewh.org) and CWHN<br />

(www.cwhn.ca) for updates.<br />

Anne Rochon Ford is the Co-Director of<br />

the National <strong>Network</strong> on Environments<br />

and Women`s <strong>Health</strong> and Coordinator<br />

of the national working group Women<br />

and <strong>Health</strong> Protection.<br />

Dolon Chakravartty is a graduate<br />

student in Public <strong>Health</strong> Sciences and<br />

Collaborative Program in Environment<br />

& <strong>Health</strong> at the University of Toronto.<br />

She is the Graduate Fellow working<br />

with the National <strong>Network</strong> on<br />

Environments and Women’s <strong>Health</strong> from<br />

the Fall 2009 - Spring 2010.<br />

FURTHER READINGS:<br />

Altman, R.G., R. Morello-Frosch,<br />

J.G. Brody, R. Rudel, P. Brown,<br />

and M. Averick. (2008). Pollution<br />

comes home and gets personal:<br />

Women’s experience of household<br />

chemical exposure. Journal of<br />

<strong>Health</strong> and Social Behavior, 49(4):<br />

417-435. Available on line through<br />

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/<br />

Steingraber, Sandra. (2007, August).<br />

The falling age of puberty in girls:<br />

What we know, what we need to<br />

know. San Francisco, CA: Breast<br />

Cancer Fund. Available on line at<br />

www.breastcancerfund.org. Steingraber<br />

is careful to point out that a<br />

myriad of factors seem to be contributing<br />

to this trend, environmental<br />

exposures being one significant<br />

one.<br />

O’Grady, Kathleen. (2008/2009,<br />

Fall-Winter). Early puberty for<br />

girls. The new ‘normal’ and why we<br />

need to be concerned. <strong>Network</strong>,<br />

11(1): 11-13. Available on line at<br />

www.cwhn.ca/en/node/39365<br />

“Managing” the Chemicals<br />

“Management” can include a wide variety of policy measures; the choice<br />

is almost enrely at the discreon of the Government of Canada. While<br />

outright bans, and placing limits on producon, use, import and<br />

emissions of dangerous substances by regulaon are all possible, they<br />

are done relavely rarely.<br />

8 FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 NETWORK

FURTHER RESOURCES:<br />

The <strong>Canadian</strong> Environmental Law<br />

Association (CELA) is a community-based<br />

environmental law clinic<br />

funded by Legal Aid Ontario, and<br />

has advocated for improvement<br />

and reform of the <strong>Canadian</strong> Environmental<br />

Protection Act for many<br />

years. For a collection of submissions,<br />

media releases and other<br />

commentary, see<br />

www.cela.ca/collections/pollution/chemicals-management-canada.<br />

The <strong>Canadian</strong> Environmental<br />

<strong>Network</strong>/ Réseau canadien de<br />

l’environnement (RCEN) has funding<br />

from Environment Canada to<br />

coordinate civil society participation<br />

in chemicals management in<br />

Canada:<br />

www.cen-rce.org/CMP/indexcmp.<br />

html<br />

Environmental Defence is an environmental<br />

group that is a member<br />

of the RCEN that “gathers, reviews,<br />

and analyses evidence related to the<br />

CMP on behalf of civil society” and<br />

makes this information available<br />

through the RCEN website. They<br />

have also mounted a campaign to<br />

encourage the federal government<br />

to designate the chemical 1,4-Dioxane<br />

as toxic. http://petition.<br />

environmentaldefence.ca/dioxane/<br />

Film: “Toxic Trespass”<br />

www.toxictrespass.com<br />

T<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Adapted from Changeons de Lunettes:<br />

Pour une approche globale et féministe de la santé,<br />

from the Réseau québécois<br />

d’action pour la santé des femmes<br />

THERE ARE MANY DIFFERENT WAYS OF CONCEP-<br />

TUALIZING HEALTH. ALTERNATIVE TYPES OF<br />

KNOWLEDGE HAVE ALWAYS COEXISTED WITH<br />

‘LEGITIMATE’ OR ACCEPTED KNOWLEDGE.<br />

Feminists have consistently played a key role in movements challenging<br />

the biomedical approach. The comprehensive feminist approach<br />

is based on eight pillars and is characterized by its critical<br />

stance toward medical and government institutions.<br />

With the new edition of the framework for women’s health,<br />

the Réseau québécois d’action pour la santé des femmes (RQASF<br />

– Quebec Women’s <strong>Health</strong> Action <strong>Network</strong>) offers a critical<br />

reading of the current situation and its causes, including the impact<br />

of globalization on our health and on our lives in general. It<br />

also proposes another vision and another approach to health.<br />

Film: “The Story of Stuff ”<br />

http://storyofstuff.com<br />

CANADIAN WOMEN’S HEALTH NETWORK FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 9

A different perspective<br />

The following are the eight pillars<br />

of the comprehensive feminist<br />

approach to health:<br />

While biomedicine is a mechanistic<br />

concept of the body that<br />

divides the individual into a collection<br />

of component<br />

parts, the comprehensive<br />

approach is<br />

based on a conception<br />

of the human being<br />

as a whole (body and<br />

mind) interacting<br />

with their social and<br />

physical environment.<br />

Thus, this approach defines health<br />

in a holistic* way, as the result of<br />

social relationships.<br />

In contrast to a homogenizing<br />

vision of health, the comprehensive<br />

feminist approach advocates<br />

the recognition of the physiological<br />

and social differences between<br />

the sexes, while at the same time<br />

recognizing the differences between<br />

individuals, both women<br />

and men. This acknowledgement<br />

of a person’s many different characteristics<br />

— whether they are a<br />

man or a woman, rich or poor, gay<br />

or straight, living with a disability<br />

or not, etc. — is called intersectionality.<br />

According to the comprehensive<br />

feminist approach, in order to<br />

improve health, the social determinants<br />

of health must be taken into<br />

account; these are the factors that<br />

have the greatest impact on health,<br />

such as income, employment and<br />

housing.<br />

Contrary to an interventionist,<br />

cure-oriented medicine, the<br />

comprehensive feminist approach<br />

believes a population’s health cannot<br />

be improved without prevention and<br />

health promotion. <strong>Health</strong> is a matter<br />

of social justice. Consequently,<br />

It is essenal to exercise<br />

vigilance and crical thinking<br />

with respect to knowledge<br />

that is presented as universal<br />

governments must not abdicate their<br />

responsibility to enact legislation and<br />

regulations in all areas that affect the<br />

determinants of health.<br />

Self-care, taking charge of one’s<br />

own health, is another of the pillars<br />

of the comprehensive feminist<br />

approach. This is something that has<br />

traditionally been promoted by Quebec<br />

feminists, particularly in women’s<br />

health centres. Self-care involves<br />

a personal effort to understand the<br />

links between our health and our life<br />

circumstances. It aims to achieve a<br />

more egalitarian therapeutic relationship<br />

based on respect, communication,<br />

and the full participation of the<br />

person consulting the health care<br />

professional.<br />

Therapists and physicians are<br />

expected to show respect for people’s<br />

autonomy and their right to<br />

informed consent. Informed consent<br />

is a fundamental right, so therapists<br />

and physicians have a responsibility<br />

to provide all available information<br />

to those who consult them.<br />

Thus, certain types of<br />

biomedical knowledge historically<br />

based on the exclusion of<br />

women must be reexamined.<br />

It is essential to exercise vigilance<br />

and critical thinking with<br />

respect to knowledge that is<br />

presented as universal,<br />

often with the support<br />

of economic interests<br />

(the pharmaceutical<br />

industry, for example).<br />

Finally, the comprehensive<br />

feminist<br />

approach to health is<br />

distinguished from the<br />

dominant medical approach<br />

in its openness to alternative<br />

approaches. However, these<br />

approaches must also be underpinned<br />

by guidelines and regulations<br />

to safeguard the rights<br />

of the individual, both in their<br />

relationship with the health<br />

professional and in their choice<br />

of the approach to health care<br />

that best suits them.<br />

The full document Changeons de<br />

Lunettes (French only) is<br />

available to order at the website of<br />

the Réseau québécois d’action pour<br />

la santé des femmes (RQASF )<br />

www.rqsaf.com<br />

The RQASF is an provincial<br />

nonprofit mulitdiscplinary organziation.<br />

Their mission is to work<br />

in solidarity to better the physical<br />

and mental health of women of all<br />

walks of life. To learn more about<br />

their activities, consult their website<br />

10 FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 NETWORK

Do<br />

pregnant women<br />

benefit<br />

from taking<br />

antidepres sants?<br />

By Jane Shulman<br />

Pregnant North American women are taking anti-depressants more than ever. The medical community has<br />

long advised women to avoid pharmaceuticals during pregnancy, but there is a growing trend to encourage<br />

women taking anti-depressants to keep taking them when they become pregnant, and to prescribe the drugs<br />

to pregnant women with depressive symptoms. The assumption being made with these prescriptions is that the potential<br />

risks to women and fetuses from taking anti-depressants outweigh the potential risks of letting depression go<br />

untreated. But is there really evidence of that these drugs benefit pregnant women, and does that benefit outweigh<br />

the potential risk?<br />

During a popular <strong>Canadian</strong> Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Network</strong> webinar last October, Dr. Barbara Mintzes discussed the<br />

history of prescription drugs during pregnancy and the current debate. Mintzes is an Assistant Professor at University<br />

of British Columbia’s Department of Pharmacology & Therapeutics, member of the UBC Centre for <strong>Health</strong><br />

CANADIAN WOMEN’S HEALTH NETWORK FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 11

Services & Policy Research, and a<br />

Steering Committee member of<br />

Women and <strong>Health</strong> Protection.<br />

She and colleagues are aware of the<br />

conflicting information about the<br />

safety and benefits of taking selective<br />

serotonin reuptake inhibitor<br />

(SSRI/SNRI) class anti-depressants<br />

(such as Prozac, Paxil and Effexor)<br />

during pregnancy.<br />

What is known is that anti-depressants<br />

are being prescribed to<br />

pregnant women ‘off-label,’ meaning<br />

prescribed for a use for which<br />

they were not approved. Mintzes<br />

explains that “Anti-depressants are<br />

unapproved for use in pregnancy<br />

in Canada, or actually in any other<br />

country.” While it is illegal for drug<br />

companies to promote their products<br />

for ‘off-label’ use, doctors<br />

can prescribe any drug for any use<br />

once it is on the market.<br />

There is a generally recognized<br />

need for caution when using medications<br />

during pregnancy that has<br />

come out of two disasters – Thalidomide<br />

and Diethylsilbestrol<br />

(DES), drugs that had devastating<br />

effects on babies born to women<br />

who took them while pregnant.<br />

In the case of Thalidomide, some<br />

babies had severe birth defects.<br />

DES caused higher rates of cancer<br />

and reproductive problems in<br />

adult women who were exposed<br />

while their mothers were pregnant<br />

with them. DES sons also have<br />

higher rates of abnormalities of the<br />

reproductive organs. Additionally,<br />

women who took DES while pregnant<br />

have higher rates of breast<br />

cancer.<br />

These disasters, Mintzes notes,<br />

brought attention to the possibility<br />

of unpredictable and long-term<br />

harm from drug use in pregnancy.<br />

With that in mind, and with the<br />

conflicting advice women were<br />

receiving about using SSRIs while<br />

pregnant, Mintzes and colleagues<br />

decided to wade through the studies<br />

that had been done to see if there<br />

was in fact evidence of benefit to<br />

taking these drugs for women and<br />

their babies.<br />

Any time a medicine is used,<br />

there is a need to weigh the potential<br />

benefit against the potential<br />

harm. This is why medicines have<br />

to be tested systematically before<br />

they’re approved for use. With<br />

‘off-label’ use – as is the case with<br />

antidepressants in pregnancy - the<br />

company marketing the drug has<br />

not had to show scientific evidence<br />

to the government of a specific<br />

benefit for this use. That evidence<br />

may or may not exist. Since all<br />

medicines can cause harm as well<br />

as benefit, unless there is rigorous<br />

scientific evidence that benefit is<br />

likely to outweigh harm, a medicine<br />

should not be taken.<br />

Mintzes worked with Patricia<br />

Fortin, a research consultant at<br />

UBC’s drug assessment group Therapeutics<br />

Initiative, Jon Jureidini, an<br />

Associate Professor at the University<br />

of Adelaide’s Department of Psychiatry<br />

and UBC Pediatrics professor<br />

Tim Oberlander. Funded mainly by<br />

<strong>Health</strong> Canada’s Bureau of Women’s<br />

<strong>Health</strong> and Gender Analysis, they<br />

carried out a systematic search for<br />

all studies comparing women with<br />

depression who did or did not take<br />

antidepressants during pregnancy,<br />

and evaluated the study results.<br />

Their conclusion? Even after<br />

searching for all published and<br />

unpublished studies – worldwide<br />

– and despite the many claims made<br />

in favour of antidepressant use, they<br />

failed to find any scientific evidence<br />

that either pregnant women or their<br />

babies benefit from use of SSRI/<br />

SNRI antidepressants.<br />

Mintzes’ team found eight studies<br />

of women who were pregnant<br />

and diagnosed with depression. In<br />

all cases, the studies compared the<br />

outcomes for mothers and babies<br />

of those taking antidepressants and<br />

those who had no treatment of<br />

any kind. There were no studies,<br />

Mintzes notes, comparing pregnant<br />

women who took SSRI/SNRIs with<br />

those who were treated in other<br />

ways, such as cognitive-behavioural<br />

therapy or regular exercise.<br />

The size and quality of the eight<br />

studies varied, as did the degree<br />

of depression of the women who<br />

participated. All were observational,<br />

meaning that although there was a<br />

control group, women who chose to<br />

take antidepressants were compared<br />

with others who did not. Interpreting<br />

the results was complicated by<br />

differences between the women<br />

who took antidepressants and those<br />

who did not. For example, some<br />

had a longer history of depression or<br />

more severe depression.<br />

Five of the eight studies were<br />

also quite small, with weaker research<br />

methods, and in those cases,<br />

Mintzes notes it was hard to say why<br />

<strong>12</strong> FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 NETWORK

there were so many poor birth outcomes.<br />

Was it the exposure to the<br />

drug, or was it because of differences<br />

between the women who were<br />

and were not taking antidepressants?<br />

Were issues like poverty, known to<br />

be a factor in depression and birth<br />

outcome, taken into account? The<br />

three larger – and more scientifically<br />

solid - studies they reviewed<br />

followed large populations of<br />

women, including one that included<br />

all women in British Columbia who<br />

gave birth between 1998 and 2001.<br />

However at the end of the review,<br />

none of the studies – whether<br />

large or small – showed any degree<br />

of benefit from antidepressant use.<br />

When there is no scientific evidence<br />

of benefit, says Mintzes, there is<br />

reason to be concerned when use of<br />

a treatment is widespread.<br />

In looking at studies in<br />

non-pregnant women as secondary<br />

evidence of whether or not there<br />

might be a benefit to pregnant<br />

women, Mintzes finds there isn’t<br />

evidence that SSRIs work better<br />

than non-drug treatment, like<br />

psychotherapy for most forms of<br />

depression, and she is concerned<br />

that the benefits of SSRIs in adults –<br />

pregnant or not – have been shown<br />

to be exaggerated. There is also the<br />

consideration that depression is<br />

often incorrectly diagnosed. A systematic<br />

review of studies found that<br />

family doctors incorrectly diagnose<br />

a person with depression 15 times<br />

for every 10 correct diagnoses.<br />

As for the impact on babies, the<br />

eight studies found that children<br />

born to women taking SSRIs had<br />

4.2% (1 in 24) greater incidence<br />

of respiratory distress than among<br />

women with depression without<br />

SSRI exposure, and a 0.6% higher<br />

rate of cardiac malformation (1<br />

in 159), again as compared with<br />

women not taking antidepressants.<br />

This is a signal that babies exposed<br />

to antidepressants seem to be doing<br />

worse in some ways than those not<br />

exposed. It adds to a larger body<br />

of literature on harmful effects of<br />

antidepressants in pregnancy.<br />

“The question is, why is this<br />

treatment being very heavily recommended<br />

for use in pregnancy given<br />

the lack of scientific evidence of<br />

benefit?” asks Mintzes. “There is no<br />

rationale for the recommended use<br />

of SSRIs in pregnancy.”<br />

Jane Shulman is the Director of<br />

Knowledge Exchange at the <strong>Canadian</strong><br />

Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Network</strong>.<br />

Watch the webinar at www.cwhn.ca<br />

CWHN is developing an in-depth information sheet about SSRIs and pregnancy available for download soon on our website.<br />

Some SSRI stats:<br />

• Andepressants are among the most frequently prescribed class of<br />

drugs for women of childbearing age in Canada.<br />

• In 2003 – 2004, 11-14% of women in Brish Columbia between the ages<br />

of 25 and 39 received at least one prescripon for an andepressant.<br />

• In 2008, 80% of women in Canada who spoke about depression to<br />

their doctors were given a prescripon, usually for an SSRI.<br />

• In 1998, just over of 2% of pregnant women in BC used an andepressant.<br />

By 2001, the rate of use had grown to 5%.<br />

CANADIAN WOMEN’S HEALTH NETWORK FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 13

CWHN Launches Webinar Series<br />

Last fall, the <strong>Canadian</strong> Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Network</strong> (CWHN) launched its new series of webinars.<br />

The interacve lecture format allows presenters to speak to and take quesons from a na-<br />

onwide audience online, and allows audience members to interact and discuss presentaon<br />

material with each other. Sessions are also recorded and available on CWHN’s website for later<br />

viewing by those who couldn’t aend the webinar.<br />

SSRIs in Pregnancy: Is there evidence of benefit?<br />

Recorded October 29th, 2009<br />

An over-capacity registraon of more than one hundred people filled the inaugural webinar<br />

featuring Dr. Barbara Mintzes, who discussed the findings of her new systemac review on the<br />

benefits and risks of an-depressant use in pregnancy. Aendees, ranging from midwives to<br />

university classes and community/social services providers, finished the session with an enthusiasc<br />

queson period. For more informaon, see the arcle on Mintzes’ research, “Do Pregnant<br />

Women Benefit from Taking Andepressants?” in this issue.<br />

The Push to Prescribe<br />

Recorded November 4, 2009<br />

In the second of the webinar series, parcipants from government, the medical professions,<br />

professors, and students tuned in to hear from three authors of A Push to Prescribe, the new<br />

book on women and <strong>Canadian</strong> drug policy. The product of 10 years of research and policy-related<br />

work by Women and <strong>Health</strong> Protecon, as moderator and editor Anne Rochon-Ford put<br />

it, the book examines prescripon drug policy in Canada and the impact on women’s health,<br />

from clinical trials to markeng. Chapter authors Colleen Fuller and Abby Lippman spoke on<br />

“Reporng Adverse Drug Reacons – What happens in the real world” and “Inclusion of women<br />

in Clinical Trials – Are we asking the right quesons?” respecvely, and engaged in an acve<br />

discussion with parcipants.<br />

Both SSRIs in Pregnancy: Is there evidence of benefit? and The Push to Prescribe, including the<br />

aer-presentaon discussion period, are available for online viewing at www.cwhn.ca<br />

More are coming up soon!<br />

Check online or subscribe to Brigit’s Notes, CWHN’s monthly newsleer, for the announcement<br />

of upcoming webinars.<br />

14 FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 NETWORK

STRENGTH<br />

in NUMBERS<br />

Project plans to unite support services for<br />

women with breast and reproductive cancers<br />

By Jane Shulman<br />

Cancer support networks in different parts of the country<br />

are looking at grouping women’s gynaecological<br />

cancers with breast cancer for the purpose of offering<br />

more support to women who have had a cervical,<br />

ovarian or uterine cancer diagnosis. Manitoba has been<br />

working on this for some time, explains Barbara Clow,<br />

director of the Atlantic Centre of Excellence for Women’s<br />

<strong>Health</strong>, and now New Brunswick and Newfoundland<br />

and Labrador are looking at their own models for<br />

delivering programming under the same umbrella.<br />

In a 2008 report for <strong>Canadian</strong> Partnership Against<br />

Cancer, called “Where Do We Go From Here? Support<br />

services for women with breast, cervical, ovarian and<br />

uterine cancer in Atlantic Canada,” Clow and co-authors<br />

looked at the idea of merging services to meet<br />

the needs of the underserved gynaecological cancer<br />

population.<br />

The idea is not without its detractors. Some have<br />

expressed concern that breast cancer groups might<br />

jeopardize their funding or lose their identity if they<br />

expand their mandate, or stretch their already overextended<br />

resources.<br />

But the focus on breast cancer over the past several<br />

years, with fundraisers and awareness campaigns popping<br />

up all over the country, means that the disease has<br />

a lot of attention, and Clow notes that it’s the kind of<br />

attention that gynaecological cancers desperately need.<br />

While she says that fewer women are diagnosed with<br />

cervical, ovarian and uterine cancers combined than<br />

breast cancer in Canada each year, with the exception<br />

of cervical cancer, their prognosis is not as good. And<br />

the psychosocial support specific to their kind of cancer<br />

just does not exist.<br />

Clow cites the work of volunteer-based Ovarian<br />

Cancer Canada as the only national gynaecologicallybased<br />

cancer group. There are no national groups for<br />

people with cervical or uterine cancer. The needs are<br />

different, but there’s overlap, which is why a program<br />

that pools resources for cancers that affect women is so<br />

appealing.<br />

The report recommendations included:<br />

Foster new research on the needs of women from<br />

vulnerable and disadvantaged communities who are<br />

faced with a diagnosis of cancer;<br />

Explore the possibility of adopting and adapting the<br />

processes and products developed by breast cancer support<br />

networks in Atlantic Canada to meet the needs of<br />

those with other women’s cancers;<br />

Promote the creation of publicly funded cancer patient<br />

navigator programs throughout Atlantic Canada.<br />

Clow says the next step is to look at how feasible<br />

this idea is, and where the desire lies. So far, nurses<br />

and service providers involved with the planning and<br />

delivering of programming are most passionate about it<br />

because they see the possibilities that lie in making the<br />

most of the services they can offer.<br />

Jane Shulman is a the Director of Knowledge Exchange at the<br />

<strong>Canadian</strong> Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Network</strong> and a former staff member<br />

of Breast Cancer Action Montreal.<br />

CANADIAN WOMEN’S HEALTH NETWORK FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 15

Women<br />

and<br />

Water<br />

Wa<br />

By<br />

Signy Gerrard<br />

“Everyone thinks we have all this<br />

water,” says Jyoti Phartiyal of the<br />

National <strong>Network</strong> on Environments<br />

and Women’s <strong>Health</strong>, when<br />

speaking of <strong>Canadian</strong>s’ attitude<br />

towards one of our most essential<br />

resources - an attitude that reflects<br />

not only an assumption that supplies<br />

of water are endless and available,<br />

but safe for everyone.<br />

This is an assumption that<br />

new research from NNEWH examines<br />

in a website launched October<br />

6, 2009 – www.womenandwater.ca<br />

– that focuses on water,<br />

women, and their relationship in<br />

Canada today. The idea for the site<br />

was born while NNEWH led a<br />

program-wide research initiative<br />

on women and water in Canada,<br />

exploring <strong>Canadian</strong> water issues<br />

16 FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 NETWORK

and the implications for women’s<br />

health.<br />

When asked about the gaps<br />

they found in research in Canada,<br />

Phartiyal immediately responds<br />

with “the biggest gap was the lack<br />

of gender analysis. It was just<br />

completely missing.” A “gendered”<br />

perspective was often limited to<br />

health as it related to fetuses or<br />

new babies. This gap was not just<br />

limited to <strong>Canadian</strong> research; few<br />

resources gave a gendered perspective<br />

on the issue of water in<br />

any developed countries. Most<br />

research discussed the relationship<br />

between women and water only<br />

in developing nations. While those<br />

studies could provide helpful information<br />

on some of the possible<br />

gender dimensions of water issues,<br />

the issues are likely to look very<br />

different in Canada.<br />

Believing that women have<br />

not only a historical and spiritual<br />

relationships with water, as well<br />

as potentially different effects on<br />

their health, the<br />

searchers, plans are to produce<br />

more documents in plain language<br />

geared towards policy makers and<br />

the general public in the future.<br />

The reports currently available<br />

on the website are organized<br />

into three themes of recent<br />

research: Aboriginal issues,<br />

Contaminants, and Privatization.<br />

In summer 2010 NNEWH will<br />

release the next volume in the<br />

Women & Water in Canada series<br />

on the gendered implications of<br />

chronic exposures to pharmaceuticals<br />

and disinfection by-products.<br />

Aboriginal water issues:<br />

According to womenandwater.ca,<br />

“as of December 31st<br />

2008, 106 First Nations communities<br />

in Canada were under drinking<br />

water advisories” – a dramatic<br />

example of the inequality of access<br />

to a vital resource. In some cases,<br />

these warnings have lasted for<br />

years. As stated in the report from<br />

the Chiefs of Ontario, Aboriginal<br />

As of December 31st 2008, 106<br />

First Naons communies in Canada<br />

were under drinking water<br />

advisories.<br />

Traditional Knowledge and Source<br />

Water Protection Final Report “in<br />

many First Nation cultures, the<br />

women of the community traditionally<br />

carry primary responsibil-<br />

researchers developing<br />

the website<br />

decided to further<br />

the discussion<br />

on women<br />

and <strong>Canadian</strong><br />

water policy by<br />

creating a central<br />

online location<br />

for information on the topic,<br />

featuring research from NNEWH,<br />

the Women’s <strong>Health</strong> Contribution<br />

Program, and key outside sources.<br />

As well as acting as an important<br />

resource for academics and reity<br />

for water.” Clearly, research<br />

needs to explore the social and<br />

cultural as well as physical health<br />

implications of poor water quality<br />

for women.<br />

The first report on this<br />

theme was created in partnership<br />

with the Prairie Women’s <strong>Health</strong><br />

Centre of Excellence. Released in<br />

April 2009, the Boil Water Advisory<br />

Mapping Project looks at the<br />

issue of water quality by examining<br />

the data available on boil water<br />

advisories in Canada – a recommendation<br />

typically made when<br />

the public has been alerted to take<br />

precautionary measures, (e.g. boil<br />

the water, at a rolling boil, for one<br />

full minute) to protect against a<br />

potential threat to health in public<br />

drinking water.. Without a standard<br />

measure of water quality in<br />

place, advisories provide a quick,<br />

although imperfect measure.<br />

As well as reviewing these<br />

advisories, the Boil Water Advisory<br />

Mapping Project highlights the<br />

important data<br />

gaps that need to<br />

be filled on topics<br />

like waterborne<br />

illnesses, the cost<br />

of water to consumers,<br />

and gender<br />

analysis in all<br />

of these issues. Future<br />

work in this<br />

area will focus on increasing the<br />

understanding of water’s meanings<br />

in Aboriginal communities, looking<br />

particularly at gender implications,<br />

as well as issues with regulations,<br />

funding, infrastructure, and more.<br />

CANADIAN WOMEN’S HEALTH NETWORK FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 17

Contaminants in water:<br />

The outbreaks of disease in<br />

Walkerton and North Battleford,<br />

when E.Coli and cryptosporidium<br />

invaded the<br />

water supply,<br />

have thrown the<br />

issue of contaminants<br />

in water<br />

into the spotlight<br />

in recent years.<br />

While Microbiological<br />

contaminants<br />

such as the<br />

ones were found<br />

in those cases remain<br />

the biggest threat; however<br />

there is growing concern over<br />

the issue of chemical contamination<br />

of water. While this form of<br />

contamination may not result in<br />

immediate and dramatic health<br />

effects, the cumulative effects of<br />

long-term exposure are a serious<br />

concern.<br />

These cumulative exposures<br />

were researched and discussed in<br />

two soon-to-be released projects<br />

– in “The Gendered Effects of<br />

Chronic Low Dose Exposures<br />

to Chemicals in Drinking Water,”<br />

by looking at data across the<br />

country, researchers concluded<br />

that although Canada’s drinking<br />

water is “for the most part safe,”<br />

the quality was tied to where you<br />

live. In the second project, “Gendered<br />

Implications of Chronic<br />

Exposures to Pharmaceuticals and<br />

Disinfection By-Products in Typical<br />

Drinking Water” looks at what<br />

is released into our water from<br />

drugs and everyday personal care<br />

products, and by-products used in<br />

water treatment, how they interact,<br />

and what the implications<br />

are.<br />

As primary caretakers, most<br />

oen responsible for the health<br />

of their families, as well as their<br />

personal health, women are<br />

likely to be affected significantly<br />

Privatization of water:<br />

The question of whether water<br />

is a human right or a commodity,<br />

and the implications of those<br />

interpretations, is addressed in the<br />

research theme of Privatization.<br />

This research area addresses the<br />

rise of private sector involvement<br />

in the water supply networks, and<br />

the more business-oriented values<br />

that the sector brings with it. What<br />

do these shifts mean for women?<br />

As primary caretakers, most often<br />

responsible for the health of their<br />

families, as well as their personal<br />

health, women are likely to be affected<br />

significantly by these trends.<br />

The Significance of Privatization<br />

and Commercialization Trends<br />

for Women’s <strong>Health</strong>, a project<br />

in partnership with the Council<br />

of <strong>Canadian</strong>s, supported by the<br />

Prairie Women’s <strong>Health</strong> Centre of<br />

Excellence and Women and <strong>Health</strong><br />

Care Reform, looks at the push to<br />

privatize water in Canada. It ex-<br />

amines larger philosophical questions<br />

such as whether water should<br />

be privatized at all, and more<br />

practical issues such as water management<br />

models,<br />

privatization experiences<br />

and threats in<br />

Canada. The project<br />

also looks at what<br />

privatization may<br />

mean for women’s<br />

health, particularly<br />

Aboriginal women’s<br />

health.<br />

Signy Gerrard is the Director<br />

of Communications at the <strong>Canadian</strong><br />

Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Network</strong>.<br />

Visit the website at:<br />

www.womenandwater.ca<br />

Read the reports:<br />

Privazaon of water:<br />

www.womenandwater.ca/<br />

pdf/NNEWH%20water%20pr<br />

ivazaon.pdf<br />

Contaminants in water:<br />

www.womenandwater.ca/<br />

pdf/NNEWH%20water%20c<br />

ontaminants.pdf<br />

Aboriginal water issues:<br />

www.womenandwater.ca/<br />

pdf/NNEWH%20water%20c<br />

ontaminants.pdf<br />

18 FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 NETWORK

WHAT WE’RE READING<br />

recommended resources from our library<br />

Rising to the Challenge:<br />

Sex and Gender-based Analysis for <strong>Health</strong><br />

Planning, Policy and Research in Canada<br />

By Barbara Clow, Ann Pederson, Margaret Haworth-Brockman,<br />

and Jennifer Bernier (2009)<br />

Rising to the Challenge is a book that describes the process of<br />

sex- and gender-based analysis and offers a collecon of case<br />

studies and commentaries that illustrate SGBA in acon. The<br />

book is of interest to people working on policy, planning and research<br />

and to people at various levels of government. It will help<br />

readers understand sex- and gender-based analysis and learn<br />

how to apply it in their work for and with women and men, girls<br />

and boys. Sex- and gender-based analysis reminds us to ask<br />

quesons about similaries and differences between and among<br />

women and men, such as:<br />

Do women and men have the same suscepbility to lung disease<br />

from smoking? Are women at the same risk as men of contracting<br />

HIV/AIDS through heterosexual intercourse? Are the symptoms<br />

of heart disease the same in women and men? Are x-rays<br />

equally useful for reflecng the level of disability and pain experienced<br />

by women and men living with osteoarthris? Do boys<br />

and girls have similar experiences of being overweight or obese?<br />

Do internaonal tobacco control policies work the same way for<br />

men and women?<br />

By introducing such quesons, sex- and gender-based analysis<br />

can help lead to posive changes in how programs are offered or<br />

how resources are allocated.<br />

To download an electronic copy or request a print copy,<br />

visit the website www.pwhce.ca, www.acewh.dal.ca,<br />

or www.bccewh.bc.ca<br />

Dissonant Disabilies:<br />

Women with Chronic Illnesses<br />

Explore Their Lives<br />

Diane Driedger & Michelle Owen<br />

(Women’s Press, April, 2008)<br />

This collecon of original arcles invites<br />

the reader to examine the key<br />

issues in the lives of women with<br />

chronic illnesses. The authors explore<br />

how society reacts to women<br />

with chronic illness and how women<br />

living with chronic illness cope<br />

with the uncertainty of their bodies<br />

in a society that desires certainty.<br />

Addionally, issues surrounding<br />

women with chronic illness in<br />

the workplace and the impact of<br />

chronic illness on women’s relaonships<br />

are sensively considered.<br />

Racialized Migrant Women<br />

in Canada: Essays on <strong>Health</strong>,<br />

Violence, and Equity<br />

Vijay Agnew (University of Toronto<br />

Press, 2009)<br />

Despite legislave guarantees of<br />

equality, immigrant women in<br />

Canada oen experience many<br />

forms of prejudice in their everyday<br />

lives. Racialized Migrant Women in<br />

Canada delves into the public and<br />

private spheres of several disnct<br />

communies in order to expose<br />

the underlying inequalies within<br />

Canada’s economic, social, legal,<br />

and polical systems that frequently<br />

result in the denial of basic rights<br />

to migrant women.<br />

CANADIAN WOMEN’S HEALTH NETWORK FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 19

Diversity and Women’s<br />

<strong>Health</strong>: No Woman Le Behind<br />

Sue V. Rosser (John Hopkins<br />

University Press, June 2009)<br />

Once focusing solely on reproduc-<br />

on and reproducve maers, the<br />

study of women’s health has expanded<br />

to include cardiovascular<br />

disease, breast cancer, colorectal<br />

cancer, osteoporosis, and more.<br />

Yet the health care issues affecng<br />

diverse groups of women remain<br />

underfunded and understudied.<br />

Diversity and Women’s <strong>Health</strong> calls<br />

aenon to this glaring discrepancy<br />

and presents cung-edge<br />

reserach on women’s health from<br />

a femenist perspecve. The contributors<br />

argue that health issues<br />

specific to lesbians, elderly women,<br />

women of colour, immigrant<br />

women, and disabled women<br />

must become a central part of the<br />

broader conversaon on women’s<br />

health in the United States.<br />

Polygendered and Ponytailed: The Dilemma of Femininity<br />

and the Female Athlete<br />

Dayna B. Daniels (Women’s Press, June 2009)<br />

Since the 1970s North American women and girls have engaged in<br />

every sport that interests them and have become champions in their<br />

fields. One of the consequences of this success is ongoing cricism,<br />

not of how they perform, but of how they look. In Polygendered and<br />

Ponytailed, Dayna Daniels argues that the femininity-masculinity divide<br />

prevents women athletes from being taken seriously in their sports. As<br />

long as sports remains a male domain, girls and women who parcipate<br />

will be viewed as either masculine to begin with or masculine through<br />

their involvement. By embracing a polygendered way of being, which<br />

emphasizes the similaries between women and men, female athletes<br />

will be given the chance to achieve their full sporng potenal and be<br />

judged for their performance, rather than their appearance.<br />

Textual Mothers/Maternal Texts<br />

Elizabeth Podnieks and Andrea O’Reilly (Wilfred Laurier University<br />

Press, December 2009)<br />

Focuses on mothers as subjects and as writers who produce autobiography,<br />

ficon, and poetry about maternity. Internaonal contributors<br />

show how these authors use textual space to accept, negoate, resist,<br />

or challenge tradional concepons of mothering and maternal roles.<br />

CWHN Info Centre<br />

The <strong>Canadian</strong> Women’s <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Network</strong> invites you to search out women’s health database,<br />

a comprehensive bilingual collecon of women’s health publicaons and resources from<br />

across Canada and the world. With advanced search opons, the CWHN women’s health<br />

database gives you access to over 13,000 resources - publicaons, research, arcles, organizaons,<br />

reviews, and projects covering a wide range of informaon on women’s health and<br />

women’s lives.<br />

Search the CWHN Info Centre at our website: www.cwhn.ca<br />

20 FALL/.WINTER 2009/2010 NETWORK