You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

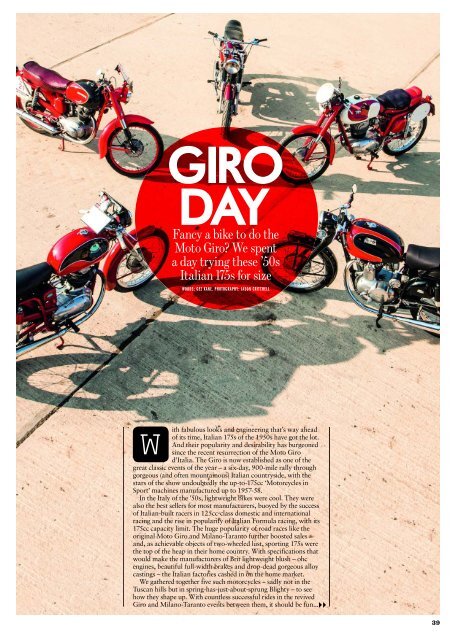

<strong>GIRO</strong><br />

<strong>DAY</strong><br />

Fancy a bike to do the<br />

Moto Giro? We spent<br />

a day trying these ’50s<br />

Italian 175s for size<br />

WORDS: GEZ KANE. PHOTOGRAPHY: JASON CRITCHELL<br />

W<br />

ith fabulous looks and engineering that’s way ahead<br />

of its time, Italian 175s of the 1950s have got the lot.<br />

And their popularity and desirability has burgeoned<br />

since the recent resurrection of the Moto Giro<br />

d’Italia. The Giro is now established as one of the<br />

great classic events of the year – a six-day, 900-mile rally through<br />

gorgeous (and often mountainous) Italian countryside, with the<br />

stars of the show undoubtedly the up-to-175cc ‘Motorcycles in<br />

Sport’ machines manufactured up to 1957-58.<br />

In the Italy of the ’50s, lightweight bikes were cool. They were<br />

also the best sellers for most manufacturers, buoyed by the success<br />

of Italian-built racers in 125cc-class domestic and international<br />

racing and the rise in popularity of Italian Formula racing, with its<br />

175cc capacity limit. The huge popularity of road races like the<br />

original Moto Giro and Milano-Taranto further boosted sales<br />

and, as achievable objects of two-wheeled lust, sporting 175s were<br />

the top of the heap in their home country. With specifications that<br />

would make the manufacturers of Brit lightweight blush – ohc<br />

engines, beautiful full-width brakes and drop-dead gorgeous alloy<br />

castings – the Italian factories cashed in on the home market.<br />

We gathered together five such motorcycles – sadly not in the<br />

Tuscan hills but in spring-has-just-about-sprung Blighty – to see<br />

how they shape up. With countless successful rides in the revived<br />

Giro and Milano-Taranto events between them, it should be fun...<br />

<br />

39

<strong>GIRO</strong> <strong>DAY</strong><br />

Q Narrow, nimble Mondial<br />

begs you to thrash it everywhere<br />

1957 MONDIAL 175 TV<br />

RACE-BRED, REVVY AND BEAUTIFUL TO BEHOLD<br />

Engine Air-cooled, 173cc, sohc single Chassis Steel single downtube cradle-type frame The numbers 10bhp, 70mph, 120kg (264lb), £5000-£6000<br />

Mondial punched well above its weight on the world stage, with<br />

the Bologna-based concern’s works racers racking up five world<br />

titles between 1949-57, plus victories in the Milano-Taranto and<br />

Moto Giro d’Italia. And their racing experience heavily influenced<br />

their road bikes. All of which is the attraction of the marque to<br />

Italian enthusiast Giuseppe Garozzo. Now a resident of Sidcup –<br />

where he ran a successful motorcycle dealership for many years –<br />

Giuseppe remains as enthusiastic about Italian metal as he was<br />

when he was a 10-year-old in his native Sicily.<br />

“Growing up in Catania, I was fascinated by bikes,” he says.<br />

“The range of lightweight machines being produced then really<br />

made a mark on me. They were beautiful. And, because I was so<br />

into the racing, the Mondial’s racing heritage really attracted me. I<br />

remember rushing home from work to listen to the day’s results<br />

from the Giro back in the ’50s, so when the event was revived in<br />

2001 I had to compete. I rode every event from 2002-2013 – and<br />

I’ve finished fourth overall twice on this bike.”<br />

Giuseppe has owned the TV for about five years. “Tom [Bolger,<br />

another of our test bike owners] called me and asked if I’d go to<br />

Italy to look at a bike to buy,” he recalls. “I already owned an<br />

earlier model of TV and quite liked it – but I was less happy about<br />

the staid styling so I said to Tom that I’d go with him on the<br />

condition that, if he didn’t buy the bike, I would. In the event, Tom<br />

bid the owner 4500 euros, but didn’t want to pay any more. The<br />

owner was firm at 5000 euros, so I bought it at the asking price.”<br />

The bike looked good. “It was much as it is now cosmetically,”<br />

says Giuseppe. “But although the seller said he had restored it, I<br />

wanted to be certain everything was right, so I stripped it. He’d<br />

done a pretty good job, but one of the valves was on the way out<br />

and the bore was a bit worn, so I wanted to sort those out properly.”<br />

That’s when Giuseppe realised the full extent of the problems<br />

facing would-be Mondial restorers. “Parts are so difficult to<br />

source,” he says. “I couldn’t find an oversize piston and rings<br />

anywhere. In the end, I had to have a new, undersized liner made,<br />

turn down the diameter of the existing piston a fraction and take<br />

some metal off the original rings to get the right gap. I found a<br />

Yamaha valve that was similar to the Mondial part and machined<br />

that down to fit. You have to be resourceful to run a Mondial.”<br />

“But the bike is so beautiful, it’s worth taking a bit more trouble<br />

over. I’ve tried to keep it as original as possible. I still run it on<br />

points ignition and it’s done 15,000 miles since I’ve owned it. With<br />

Mondial’s racing heritage, how could I resist?”<br />

Left-side kickstarts are the order of the day on Italian<br />

lightweights of this era and the Mondial needs only a gentle swing<br />

to burst into surprisingly noisy life. It sounds like the race-bred<br />

thoroughbred it is. A fair few revs are vital to make a brisk<br />

getaway, but once on the move, keeping the free-revving engine on<br />

the boil using the sweet down-for-up gearbox is a delight.<br />

The bike is so narrow, light and nimble, I feel I could almost<br />

ride it flat out everywhere – and the full-width brakes are pretty<br />

effective at scrubbing off a bit of speed should the occasion<br />

demand. After 200 miles of a Giro stage, maybe that seat wouldn’t<br />

feel quite as great as it looks, but on the sort of roads we’re riding<br />

today – a mixture of minor B-roads and unclassified lanes – I<br />

really feel the Mondial is all I need.<br />

OWNING ONE: Go for completeness, counsels Giuseppe.<br />

“Because Mondial were a fairly small-scale producer, parts are<br />

scarce. But because of that, models like this are appreciating in<br />

value and it makes sense to spend a bit to keep them in good<br />

condition. You’ll either need a contact in Italy to source whatever<br />

is remaining, or get parts re-manufactured.<br />

40

‘I’VE FINISHED<br />

FOURTH OVERALL<br />

IN THE <strong>GIRO</strong> TWICE<br />

ON THIS BIKE’<br />

Giuseppe Garozzo<br />

41

???????????????<br />

‘I GOT STUCK IN AND<br />

THE RESTORATION<br />

TOOK JUST FOUR<br />

MONTHS’<br />

Chris Bushell<br />

42

Q Pure Ducati: Desmo<br />

valve gear, taut handling<br />

1957 DUCATI 175T<br />

FUN AND RELIABLE IF SHIMMED UP CORRECTLY – AND YOU CAN GET PARTS!<br />

Engine: Air-cooled, 174cc, sohc single Chassis: Steel, tubular open-cradle type The numbers: 11bhp, 68mph, 104kg (230lb), £5000<br />

Chris Bushell has built his Ducati 175T to be ridden – and that’s<br />

exactly what he’s done since he restored it over the winter of<br />

2001-02. Chris was converted to Italian bikes in 1980 when he<br />

bought a Morini 3½. “That was the thin end of the wedge,” he<br />

smiles as he prepares to hand over his 175T to me. “I bought my<br />

first Ducati in 1992 and since then I’ve only owned Ducatis.”<br />

Chris has ridden nine Moto Giros on this bike, so I reckon it<br />

will be well up to our ‘Mini Giro di Kent’ today. With the beveldrive<br />

ohc engine blatting away healthily beneath me, first<br />

impressions are good. The Ducati feels bigger than it is thanks to<br />

the braced scrambles-type ’bars Chris has fitted to give a more<br />

comfortable riding position for long days in the saddle.<br />

Acceleration is lively enough to keep out of the way of modern<br />

traffic on the backroads and the handling is taut and predictable.<br />

After a winter layoff, the brakes could probably stand a little<br />

fettling, but with a mere 104kg to haul up I’m sure they’ll be fine<br />

after a little bedding in. Keeping the revs above 6000rpm liberates<br />

the best of the power and, though I have to drop to third for a<br />

couple of hills, it’s great fun keeping the motor spinning in its<br />

sweet spot. By the time we’ve covered a few miles, I’m really<br />

getting into it – sticking close to the bike in front, slipstreaming<br />

and keeping the throttle pinned through bends, it’s hard to believe<br />

just how much fun you can have at modest speeds.<br />

So how did Chris turn a £490 autojumble buy into a Moto Giro<br />

veteran? “It certainly sounds like a bargain now,” he admits.<br />

“I had bought a 125 Sport and rode that in the first of the revived<br />

Moto Giros in 2001. I was the only English rider there. I had a<br />

great time, but the 125 really struggled on some of the hills and<br />

I started to look for a 175. I spotted this one at Netley Marsh in<br />

2001. It looked terrible, but amazingly it ran. I stripped it right<br />

down and got the frame and all the tinware blasted and painted.<br />

It wasn’t as bad as it looked and everything was repairable.”<br />

Chris was pretty lucky with the engine, too, conceding: “It was<br />

reasonable. I had to source new primary drive gears and I replaced<br />

every bearing, seal and gasket. I also renewed the valve guides and<br />

seats and rebored the barrel to suit an NOS piston and rings but,<br />

like any Ducati, I spent most time shimming up the rebuilt engine.”<br />

Shimming up Ducati engines is a mix of art and science,<br />

according to Chris. “You get a feel for it after you’ve done it a few<br />

times. You need the right tools – micrometer, vernier calipers,<br />

vernier depth gauge – and a genuine manual. I buy any Ducati<br />

manuals I see and, fortunately, I had an English language copy for<br />

the 175T. It takes time and patience to set up the end float<br />

accurately, but once you’ve got it right, the engine is super reliable.<br />

The engine of this bike has only been apart once since 2001 – and<br />

that was just to clean out the integral sump.”<br />

Like many Giro riders, Chris has opted to stick with coil<br />

ignition, valuing the ease of roadside repairs over an electronic<br />

replacement. “I fit a new condensor before each Giro and carry<br />

spares,” he says. “I got stuck in and the restoration took just four<br />

months. The bike was ready for the 2001 Moto Giro and it made<br />

the event so much easier and more enjoyable. Since then, it’s never<br />

let me down and it’ll cruise all day at 55-60mph.If you steer clear<br />

of dual carriageways and motorways, it’s a very usable bike.”<br />

OWNING ONE: Good parts availability is one good reason to<br />

go for a Ducati, says Chris. “There are a lot of common parts on<br />

models built from 1957-68. I get most engine parts from Jonathan<br />

White in the USA (provajon@gmail.com) or Road and Race in<br />

Australia (roadandrace.com.au). Paul Klatkiewicz of Ducati<br />

Technical Services (01924 860210) or Nigel Lacey (laceyducati.co.<br />

uk) are very helpful. A project will cost at least £1500-1800.<br />

43

<strong>GIRO</strong> <strong>DAY</strong><br />

Q Racing crouch is<br />

advisory at 8000rpm-plus<br />

1956 PARILLA LUSSO VELOCE<br />

VISUALLY STUNNING RACER FOR THE ROAD, WITH AN ENGINE THAT’S A WORK OF ART<br />

Engine: Air-cooled, 174cc ohv single Chassis: Steel, tubular open-cradle type The numbers: 14bhp (est), 70mph, 100kg (220lb), £6500<br />

It looks as Italian as pasta, yet the marque’s founder was Spanishborn.<br />

At first glance you’d swear it has an ohc engine, but a closer<br />

look reveals it’s a high-cam ohv unit. The Parilla story may be full<br />

of quirks and contradictions, but there’s no denying that Tom<br />

Bolger’s 175cc Lusso Veloce is a stunning motorcycle.<br />

Tom says: “I’m a relatively recent convert to Italian bikes.<br />

I bought an MV Agusta 750 Oro (the first, limited production<br />

version of the F4) in 1999. I entered the 2005 Moto Giro on it, but<br />

it was a disaster. All these little bikes kept flying past me on the<br />

outside on the tight hairpins of the mountain descents. I thought:<br />

‘I’ll have to get one of those,’ and started looking when I got home.”<br />

Tom knew Mike McGarry – who runs a Parilla website – and<br />

contacted him. “I knew about Parilla’s racing history,” says Tom.<br />

“And I really liked the look of them. Mike knew a guy in North<br />

Wales who was selling one, so I bought it. It was a non-runner and<br />

leaked oil like a sieve, but it was complete and quite tidy. I stripped<br />

the engine completely and got to work as soon as I got it home.”<br />

The Parilla engine is a work of art. “For the mid-’50s this is an<br />

amazing little machine,” says Tom. “They were racers on the road.<br />

The high-cam design, with its unusual single-lobe camshaft,<br />

means the engine revs to 8000rpm-plus, and the gearbox is a<br />

cassette-type that you can remove with the engine in the frame.<br />

I’ve fitted a hotter X1 cam and a big-valve MSDS racing head I<br />

found in the States. I’m running a 22mm carburettor (standard is<br />

20mm), but some owners go up to a 25mm. Power is definitely up<br />

compared to a standard motor, but I don’t know by how much.”<br />

Tom has incorporated other subtle yet practical modifications.<br />

“The ignition is a Power Dynamo electronic set-up and the stock<br />

two-plate clutch is a known weakness. Gary Emmerson<br />

(motoparilla.co.uk) makes a kit to allow you to fit a seven-plate<br />

Ducati clutch, but you do need to use the later, wider clutch cover.”<br />

With the cosmetics of the bike already in good order, Tom was<br />

ready for a more enjoyable Giro in 2006, riding the Lusso Veloce<br />

in the prestigious historic class. And he’s stuck with Parilla power<br />

since then. “I parked up next to another Parilla at the end of a<br />

hard day’s stage at last year’s event and the owner couldn’t believe<br />

I’d just finished the stage,” Tom says. “He thought I’d cleaned my<br />

bike before parking it up. His bike was covered in oil, but mine<br />

doesn’t leak a drop. It’s all about careful preparation.”<br />

Barrelling along a Kentish lane on Tom’s bike, I soon realise he’s<br />

right about the bike feeling just like a racer on the road – the little<br />

bike feels taut and responsive as I snick through the gears and<br />

swing through bends, trying my best to avoid scrubbing off an<br />

ounce of speed by touching the excellent full-width brakes.<br />

The ’bars are narrow and low, positively encouraging a racing<br />

crouch to maximise the effect of the tiny frontal area of the<br />

Parilla. And that clutch conversion is worth every penny –<br />

whatever it cost. With Tom exhorting me to use a few more revs,<br />

I really appreciate its silky-smooth action and the ease with which<br />

I can juggle revs and ratios to maximise velocity.<br />

My ride on Tom’s Parilla has really opened my eyes to the<br />

potential of this little bike. I can easily see why Tom loves nothing<br />

better than hammering it round the Moto Giro for six days at a<br />

time. Smooth, sophisticated and oh-so stylish, this isn’t just a great<br />

lightweight machine, it’s a great bike – full stop.<br />

OWNING ONE: Though Parillas are rare (and consequently not<br />

cheap), there are still bargains to be found in the USA and Italy,<br />

according to Tom. “You shouldn’t need many spares anyway,” he<br />

claims. “You can find just about everything if you look hard<br />

enough and some parts are being re-manufactured.” A good<br />

ready-to-ride Lusso Veloce will cost around £5000-£6000.<br />

44

‘FOR A BIKE MADE<br />

IN THE MID-’50S, IT’S<br />

AN AMAZING LITTLE<br />

MACHINE’<br />

Tom Bolger<br />

45

???????????????<br />

‘I BOUGHT THIS<br />

BIKE TO GET INTO THE<br />

<strong>GIRO</strong>, BUT I SOON<br />

GREW TO LOVE IT’<br />

Chris Halfknight<br />

46

Q Comfy position and torquey<br />

engine make 200-mile days a doddle<br />

1958 MV AGUSTA 175 AB<br />

A CLASS ACT AND A GREAT ALL-ROUNDER FOR THE <strong>GIRO</strong> (APART FROM THE SEAT)<br />

Engine: Air-cooled, 172cc, ohv single Chassis: Steel, tubular open-cradle type The numbers: 7.5bhp, 60mph, 123kg (271lb), £6000<br />

If a bike can hold the key to redemption, Chris Halfknight’s MV<br />

Agusta is one machine that does. An increasingly hectic period<br />

spent thrashing big-bore sports bikes at licence-threatening speeds<br />

has given way to a passion for Italian lightweights – and the roadbased<br />

events in Italy that are tailor-made for them. “I’ve packed<br />

up the sports bike,” smiles Chris. “I don’t even ride much in the<br />

UK any more. Events like the Giro and the Milano-Taranto have<br />

spoiled me. I can’t get enough of them. I’m even learning Italian.”<br />

That’s serious. Just what changed the mindset of the former<br />

rocker? “Blame Tom Bolger,” Chris laughs. “He knew I’d been<br />

blasting around on sports bikes, but he suggested I give the Giro a<br />

go. I’d never even heard of it, but I agreed to give it a go when Tom<br />

told me he knew of an MV for sale in Essex. We went over to have<br />

a look and that was the start of it. The owner said the crank had<br />

run a bearing, but that he’d had another crank modified to take a<br />

Kawasaki roller-bearing big-end that he’d include with the deal.<br />

I took a chance, brought the bike home and stripped the engine.”<br />

A pushrod single held no terrors for former Jaguar mechanic<br />

Chris. “It’s really the simplest engine to work on,” he confirms. “If<br />

you can manage a Honda CG125, you can manage one of these.”<br />

Once he was inside the engine, Chris realised things weren’t as bad<br />

as the previous owner had believed. “The original crank, with its<br />

white-metalled big end, wasn’t in bad condition at all,” he says.<br />

“The main problem was a bent exhaust valve. There was even a<br />

nearly-new piston and rings. I replaced the bent valve, fitted the<br />

roller-bearing crank as a precaution and re-assembled the engine.”<br />

Tom had told Chris about the benefits of the Power Dynamo<br />

electronic ignition systems and he was keen to fit one to the MV.<br />

“The problem was that Power Dynamo don’t produce a kit to suit<br />

the Model AB,” he says. “But a chance conversation with a guy at<br />

the Bristol classic show led to him offering to make me a one-off<br />

adaptor to enable me to use a kit intended for an earlier CSTL<br />

model. The self-generating Power Dynamo system is brilliant.”<br />

Owning an MV would be enough for many people, but for<br />

Chris, the real draw is the events he gets to ride on his immaculate<br />

red and white AB. “I’m really competitive,” he admits. “The Giro<br />

is a real riding experience. The time schedules are so tight, you<br />

have to ride flat-out all day. I love it. A pre-’59 175 is what you<br />

need to get in, so I’ve got one. But I soon grew to love the bike.<br />

“It’s the best bike I’ve ever owned,” announces Chris with all<br />

the zeal of a true convert. “I’ve finished six Giros and a Milano-<br />

Taranto on it. I won my class in the 2012 Milano-Taranto and<br />

finished fifth overall, as well as winning a couple of the daily time<br />

trials. That’s not bad going from a little ohv model.”<br />

As I head off up the road, I appreciate its qualities almost at<br />

once. The handlebars are flat and comfortable, the Air Hawk air<br />

cushion seat cover transforms the narrow stock seat (“a hard seat<br />

will kill you on the Giro,” says Chris) and the pleasantly torquey<br />

engine makes 50-55mph cruising easy – and enjoyable.<br />

There’s a feeling of quality about the MV, too. There’s a<br />

reassuringly solid feel to the ride, the handling is more than a<br />

match for the modestly-tuned engine and the brakes offer dramafree<br />

stopping. This is a bike I could happily tackle the Giro on.<br />

OWNING ONE: The owners’ club should be your first stop for<br />

parts. New Old Stock spares are getting rarer, but the club<br />

(mvownersclub.co.uk) hold stocks and re-manufacture some hardto-find<br />

parts. “Italy is definitely the place to go for bargains,<br />

though,” counsels Chris. “Italians just don’t seem to buy this sort<br />

of bike, so you can still find good buys. I’ve found that the<br />

websitemoto.it/moto-epoca is a good place to find bikes. A budget<br />

of around £5000-£6000 should find you a good one.”<br />

47

<strong>GIRO</strong> <strong>DAY</strong><br />

Q Not the fastest or most<br />

elegant, but a fine Giro steed<br />

Q Bike is a veteran of<br />

CB-sponsored Mini Giro GB<br />

1954 MOTO MORINI TOURISMO<br />

A DEFINITE CONTENDER FOR ‘IDEAL FIRST MOTO <strong>GIRO</strong> BIKE’<br />

Engine: air-cooled, 172cc, ohv single Chassis: Steel, tubular open-cradle type The numbers: 5.8bhp, 58mph, 101kg (223lb), £3500<br />

The Moto Morini Tourismo clattering busily away beneath me<br />

may not be the most exotic – or, indeed expensive – of our mini<br />

test fleet today, but it certainly scores highly on rider friendliness.<br />

A home-made small-end bush that’s on the way out after five years<br />

of hard use explains the rattly top end, but its excellent ergonomics<br />

and torquey power delivery make me feel instantly at home on it.<br />

Proudly wearing peeling numberplates from the Classic Bikesponsored<br />

Mini Giro Great Britain in 2009, Pete di Pasquale’s<br />

black and red Tourismo amply proves the point that you don’t<br />

need the fastest, most collectable or most valuable machine to<br />

thoroughly enjoy the world of Italian lightweights. The gearlever<br />

has a fairly long throw, but with fourth gear in the up-for-up<br />

gearbox engaged, there’s little need to change down, save for the<br />

biggest hills. That softly-tuned little ohv engine just keeps<br />

chugging away. And, though the brakes are ‘only’ half-width hubs,<br />

they’re quietly effective – as I discover when I roll over a brow to<br />

be confronted with a steep drop and right-angle bend. If I was<br />

heading off to Italy to tackle my first Giro this year, I’d be very<br />

pleased to have a bike like Pete’s Morini to share it with.<br />

As you might guess from his name, Peter di Pasquale has more<br />

than a drop of Italian blood in him. In fact, his Christian name is<br />

Piero and he was born in Terni – the home town of the club that<br />

revived the Moto Giro d’Italia back in 2000. There’s no way Pete<br />

– a Kent resident for more than 30 years now – wasn’t going to<br />

take in a Giro or two. And in 2000, he got the call from Giuseppe<br />

– another of today’s band of brothers. “The trouble was,” Pete<br />

recalls, “I didn’t have a bike to do it on. So I started looking and<br />

spotted this Morini for sale in the VMCC magazine.”<br />

Pete offered the owner a swap for a Benelli 254 and a deal was<br />

done. “I don’t know if I got the best of it, though,” he continues.<br />

“The Benelli was on the button, but the Morini was in a bit of a<br />

state. Still, I had a Giro-eligible bike and two months to sort it out.<br />

The dynamo was faulty and I couldn’t find a replacement in time,<br />

so I took a spare battery and charger and charged the battery<br />

every night. I made it through three days like that. The following<br />

year the electrics burnt out completely and the engine seized, so I<br />

vowed to sort the bike out properly before the next event.”<br />

Pete bought a replacement dynamo and a spare engine. “I<br />

thought I’d sort the spare engine and fit that,” he says. “Then I<br />

could go through the original engine and make a proper job of it.<br />

The ‘new’ engine needed a piston and I couldn’t find one<br />

anywhere, so I bought a pair of NOS BSA A7 pistons – the A7 has<br />

the same bore and stroke – and used one. The BSA gudgeon pin is<br />

a larger diameter than the Morini one, so I had to machine some<br />

brass bushes to suit. I should have used bronze, but I couldn’t find<br />

any at the time. The brass bushes have lasted five years, but they’re<br />

about shot now. That’s why the top end is rattling so badly.”<br />

But now the original engine is ready to go back in. “I’ve fitted a<br />

new conrod with the flywheels bored to accept the A7 gudgeon<br />

pin,” he says. “It also needed a new gearbox selector shaft and I’ve<br />

made up new bushes for the rockers. The lubrication to the rocker<br />

shafts is a bit marginal, so they wear. I’ve also got Power Dynamo<br />

ignition for it, so it’ll be good to get it back in the bike now.<br />

“It might not be the fastest bike in its class, but it comfortable<br />

and reasonably torquey – two important attributes for a bike<br />

you’re spending six long days on. The tank is usefully large and<br />

fuel consumption is great. I can get 70mpg from mine.”<br />

OWNING ONE: Spares are getting rare, although North<br />

Leicester Motorcycles (northleicestermotorcycles.com) can help<br />

with some parts. The simple, under-stressed engine is easy to work<br />

on but you do need to check the oil feed to the rockers.<br />

48

‘IT’S COMFORTABLE<br />

AND FAIRLY TORQUEY<br />

– BOTH IMPORTANT<br />

FOR THE <strong>GIRO</strong>’<br />

Piero (Peter) di Pasquale<br />

49

HOLY CHRIST, I<br />

thought I was<br />

going to die!”<br />

When the man<br />

uttering the<br />

sentiment is one<br />

Michael Rutter<br />

Esq., whose CV of<br />

road racing achievements is<br />

longer than most people’s life<br />

story, you take notice. It must<br />

take something pretty hairy to<br />

widen the eyes of a 13-times<br />

NW200, eight-times Macau and<br />

four-times TT winner.<br />

On this occasion, though,<br />

we’ve merely ridden five miles<br />

across town to fill up at a garage.<br />

Michael smiles. “There are<br />

usually fewer cars around when<br />

I’m on a bike,” he explains.<br />

Rutter, myself and Johnny<br />

Mac brim the three red machines<br />

before heading off for a day<br />

tearing Lincolnshire a new one.<br />

As I pay for the fuel I look out<br />

over rows of chewing gum, and<br />

across at the forecourt where the<br />

Yamaha R1, Ducati 1299 S and<br />

BMW S1000RR are gathered<br />

round the pump, huddling in a<br />

conspiracy of outrageous<br />

performance.<br />

I run through numbers in my<br />

noggin: the Yam is 190bhp, the<br />

BMW 196bhp, so too the Ducati.<br />

With a good launch they’ll hit<br />

180mph from a standstill in just<br />

over half a mile. In top gear, they<br />

take less than 10 seconds to roll<br />

on from 40mph to 120mph. That<br />

is just nuts.<br />

But all three are festooned<br />

with cutting-edge, race-derived<br />

electronic technology that<br />

makes such extreme<br />

performance a) possible and b)<br />

not just survivable, but an<br />

absolute hoot to use. Getting<br />

away with it has never been so<br />

hilariously, outrageously easy.<br />

Eighteen years ago the scene<br />

would have included the original<br />

R1, perhaps Aprilia’s RSV Mille,<br />

or a Ducati 916; maybe a ZX-9R.<br />

Great bikes, thrillingly explosive<br />

in their day. But the new breed of<br />

electronically-enhanced litre<br />

sportsbikes quicken the pulse<br />

like never before, no matter how<br />

old and doddery we’re getting.<br />

You’re never too washed-up for a<br />

race rep, and they still reduce us<br />

to giggling kids. Although<br />

watching Johnny and Rutter<br />

clowning about with paper<br />

towels as they wait at the pumps,<br />

it’s not as if they need help...<br />

We fire up in a supersonic<br />

thunder of mixed firing<br />

intervals, massive 90° V-twin<br />

detonations mingling with the<br />

V4-esque warble of Yamaha’s<br />

crossplane motor and the<br />

straight mechanical bark of<br />

BMW’s 180° inline four. Out of<br />

the garage, we fight through<br />

queues of crawling traffic to get<br />

to the interesting roads. But it<br />

gives us the chance to get an idea<br />

of the new R1 away from its<br />

natural, open road habitat.<br />

“The Yam is a small bike with<br />

a big riding position,” says<br />

Johnny before we ride<br />

off. “It reminds me of<br />

the Aprilia RSV4. Nice<br />

big seat, bars are<br />

reasonable; I could go a long way<br />

on it. It looks like it’s going to be<br />

torture, but it’s not.”<br />

He’s right. The Yamaha is<br />

small, but not ridiculously,<br />

250 tiny. It’s R6-sized, which<br />

means it looks like it won’t fit<br />

when you eye it up warily from a<br />

distance, but as soon as you’re<br />

onboard it feels just about big<br />

enough. Compact, ready for<br />

action, but not daft.<br />

And the front-end biased<br />

riding position of the<br />

previous R1, which seemed to<br />

plant the headstock directly<br />

below the rider’s groin and<br />

loaded wrists with lead, is gone.<br />

Instead the R1 now feels<br />

balanced at standstill, body<br />

weight spread evenly, and even<br />

more balanced on the move. The<br />

first impression is of<br />

featherweight and agile steering.<br />

I remember rolling out of the<br />

pitlane at Eastern Creek in<br />

On the road, Yamaha’s new R1, BMW’s revised S1000RR<br />

and Ducati’s souped-up 1299 S are so off the scale it’s<br />

hard to say anything sensible about them. But fun trying...<br />

S1000RR v R1 v 1299 S<br />

ON THE<br />

w i t h M i c h a e l<br />

50<br />

PERFORMANCEBIKES.CO.UK | JUNE 2015

THE RUTTER TEST / S1000RR v R1 v 1299 S<br />

Words Simon Hargreaves / Photography Chippy Wood<br />

ROAD<br />

R u t t e r<br />

JUNE 2015 | PERFORMANCEBIKES.CO.UK 51

Australia on the 2009 crossplane<br />

R1 and being immediately<br />

surprised at how much force it<br />

needed merely to roll the thing<br />

from side to side (a feeling that<br />

never entirely went away).<br />

The new R1 is completely<br />

different. It flicks left to right<br />

and back like a Peter Powell<br />

stunt kite in a gale, warming my<br />

early morning brain as much as<br />

putting heat into the tyres. The<br />

chassis has an instant rightness<br />

that makes me smile, and give<br />

the other two on the BMW and<br />

Ducati a thumbs up.<br />

The oncoming traffic clears<br />

for a moment, so I let a few of the<br />

R1’s demons slip loose. The<br />

motor spools up like a turbine for<br />

a micro-second, then eviscerates<br />

the nose-to-tail line of cars and<br />

lorries, turning them inside out<br />

and leaving them spinning,<br />

gutted, in the wake of the<br />

Yamaha’s howling, shattering<br />

pace. I mean, really: holy fuck,<br />

what an engine. What. An.<br />

Engine. For all the guff Yamaha<br />

made about the mechanicals<br />

inside the previous R1 being<br />

derived from Valentino Rossi’s<br />

M1, and how the crossplane<br />

crank produced ‘pure’ torque<br />

that felt intimately connected<br />

the throttle, that engine feels<br />

like a truck motor compared to<br />

this thing.<br />

No word of a lie, as I ride along<br />

casually deploying its weaponsgrade<br />

acceleration, the machine<br />

the Yam reminds me of most is<br />

Honda’s RC211V, the 990cc<br />

MotoGP tool I was lucky enough<br />

to ride back in 2005. That bike<br />

had been dialled back by HRC<br />

technicians from full race spec to<br />

a softer, journo-friendly 200-odd<br />

bhp. It has taken 10 years to get<br />

the same feeling of<br />

incomprehensible, but<br />

invincible, performance on the<br />

road. But here we are, and the<br />

Yamaha R1 definitely has it. It<br />

feels like the power curve is a<br />

near-vertical ramp, especially<br />

between 7000 and 9000rpm.<br />

The new R1 motor is<br />

substantially narrower than the<br />

old bike’s, with a lighter<br />

crossplane crank, revised, lighter<br />

counterbalance shaft, titanium<br />

rods, wider bores and shorter<br />

stroke, finger rocker valve gear<br />

and redesigned head. This<br />

should amount to more revs,<br />

more power, sharper engine<br />

response and lighter steering.<br />

And it does. The Yamaha<br />

romps through the early<br />

morning river of commuting tin<br />

boxes like a bionic eel weaving<br />

effortlessly upstream, driving<br />

relentlessly forward in a flood of<br />

quickshifting shortshifts.<br />

Awesome though its engine is,<br />

the R1 is not flawless. The<br />

quickshifter is fine on upshifts,<br />

but coming the other way down<br />

the box is a bit hit and miss,<br />

That burger van’s<br />

just around the<br />

next corner<br />

The R1’s engine<br />

is a phenomenal<br />

exercise in<br />

rocketship<br />

power delivery<br />

The R1 feels<br />

quicker for the<br />

least input<br />

Power: nothing without control<br />

‘Where the Tommy Hillfinger?’<br />

52<br />

PERFORMANCEBIKES.CO.UK | JUNE 2015

THE RUTTER TEST / S1000RR v R1 v 1299 S<br />

‘The motor spools up like a turbine<br />

then turns the line of cars inside out,<br />

leaving them spinning in its wake’<br />

especially with an insanely tall<br />

first gear – I often find myself<br />

trying to shift down into a gear<br />

below. Rutter has the same issue:<br />

“It’ll do over 100mph in first,” he<br />

points out. “This isn’t going to be<br />

much fun in hairpins. There’s a<br />

lot of engine braking, too, and<br />

it’s easy to lock the rear.”<br />

Throttle response needs fine<br />

judgement to avoid jerkiness. I’m<br />

not sure if it’s a fuelling thing; I<br />

reckon the actual grip is<br />

physically stiff to turn, as if the<br />

rubber is fouling the bar end (it<br />

isn’t) or a cable is trapped (it isn’t<br />

either). The S1000RR’s fly-bywire<br />

grip turns like a lightlysprung<br />

volume dial in<br />

comparison. Either way, I find<br />

myself using a combination of<br />

clutch and rear brake to smooth<br />

things out. We stop for a coffee<br />

and I mention the problem.<br />

“What mode are you in?” asks<br />

Johnny Mac. Er, it says Mode 1<br />

on the big colour screen. We<br />

used to call them clocks, but<br />

that’s no longer sufficient. Is it<br />

officially now a dash? A swarm<br />

of acronyms and pictograms is<br />

very cool but will anyone be<br />

admiring the brake pressure<br />

monitor when their eyeballs are<br />

glued to the visor?<br />

“Try it in Mode 3,” suggests<br />

McAvoy. “It’s the same power<br />

and delivery, just with softer<br />

throttle response.” Rutter nods.<br />

With no manual, we stab at<br />

buttons – a rocker switch system<br />

on the left bar, a scroll wheel on<br />

the right. Once you work it out,<br />

it’s fairly simple to master.<br />

We hammer off again into the<br />

Lincolnshire Wolds. The throttle<br />

still feels stiff. But the roads are<br />

dry, the tarmac is warming up,<br />

and the R1 starts to deliver on its<br />

promise of A-road supremacy.<br />

It’s truly, madly, deeply sublime,<br />

pulling wheelies off crests with<br />

electronically-controlled<br />

accuracy, back end sucking into<br />

the tarmac and releasing grip in<br />

tiny, metered stages of slippage<br />

– and all the while with the<br />

droning, baleful moan of a<br />

bewitching powerplant. It’s<br />

sportsbike heaven. In fact R1 is<br />

so calm and collected at speed, it<br />

doesn’t feel significantly faster<br />

than the other two. But it gets<br />

where it’s going so much sooner<br />

than either of them that it must<br />

be. No wonder Rossi cuddles his<br />

M1 all the time. Surprised he<br />

doesn’t nip off with it for a<br />

quickie. It flatters your riding,<br />

inspires new confidence to go at<br />

it harder – not faster, as such,<br />

just smoother and better.<br />

We swap bikes and I take the<br />

BMW S1000RR. Michael Rutter<br />

is raving about it: “It’s fucking<br />

beautiful. You feel like you could<br />

ride a million miles on it and<br />

then go racing with it without<br />

even thinking about it. Thank<br />

God for the heated grips early on<br />

though – without them I’d have<br />

said ‘Fuck it,’ and turned round<br />

and gone home.”<br />

I covered 10,000 miles on the<br />

original S1000RR in 2010 and<br />

around 4000 on the tweaked<br />

2012 model. I’ve also ridden this<br />

bike before, at the launch. So I<br />

know it’s going to feel amazing.<br />

It’s basically taken the cool bits<br />

of the old HP4 – semi-active<br />

suspension, enhanced<br />

electronics and braking, engine<br />

tweaks – and added them to the<br />

S1000RR package. Until the R1<br />

was announced, it sounded<br />

unbeatable.<br />

But after riding the Yamaha,<br />

the S1000RR – yes, I know this<br />

sounds crackers – feels large,<br />

doesn’t turn as sweetly; it’s more<br />

practical and road-oriented than<br />

the R1, a feeling backed up by<br />

heated grips, cruise control and<br />

the best quickshifter and<br />

autoblipper of the three. Rutter’s<br />

impressed: “You’d never think<br />

you’d need them on the road, but<br />

they’re just fantastic. Now I’ve<br />

tried it, I wouldn’t buy a bike<br />

without one.” Purists may mock,<br />

but this stuff is genuinely useful.<br />

The BM also has a roomier<br />

riding position than the R1, with<br />

a longer reach to the bars. “The<br />

S1000RR is the most<br />

JUNE 2015 | PERFORMANCEBIKES.CO.UK 53

‘The burbling from the collector box<br />

as unburned fuel ignites on the<br />

overrun is pure Group B rally car’<br />

The new R1,<br />

pictured here in<br />

its natural habitat,<br />

under a TT winner<br />

‘Are you that John McGuinness?’ Yep, they’ll outrun a Piaggio MP3<br />

conventional, and feels like an<br />

evolution of previous inline four<br />

litre sportsbikes,” says McAvoy.<br />

“The R1 and the Ducati are<br />

doing something different<br />

mechanically, and have a more<br />

contemporary riding sports<br />

riding position.”<br />

The BMW is noisy, too, with a<br />

lot of chain whine and howling<br />

inline four exhaust note. It<br />

sounds harsh against the musical<br />

purr of the Yamaha and the<br />

basso profondo of the Ducati –<br />

but the burbling from the<br />

collector box as unburned fuel<br />

ignites on the overrun is pure<br />

Group B rally car.<br />

As the big hand moves past<br />

midday, I realise that although<br />

the S1000RR doesn’t ignite quite<br />

the same intensity of seething<br />

passion as the Yam (and we’re<br />

talking fractions of a degree of<br />

trouser arousal), it’s a much<br />

better road bike. The engine is<br />

more tractable, with a bigger<br />

shunt off the bottom end and up<br />

to 7000rpm, the riding position<br />

is roomier, the fairing and screen<br />

are taller and keep more wind<br />

off, the handling is steadier and<br />

the motor is less inclined to land<br />

you laughing maniacally in front<br />

of a magistrate.<br />

It’s also a lot less thirsty; both<br />

the R1 and the Ducati are<br />

perfectly capable of sucking<br />

petrol away at 25mpg on the<br />

road while the BM does nearer<br />

40mpg for the same pace. It<br />

means the Beemer gets close to<br />

150 miles on a tank while the<br />

other two are under 100. That’s<br />

a big difference – sod the money,<br />

it’s an extra pit stop even on a<br />

short run.<br />

Ducati time. The 1299<br />

Panigale S is basically a<br />

big-bored 1199 Panigale, with<br />

enhanced electronics and, on the<br />

S model, semi-active suspension.<br />

Technically, to wrest this<br />

much power from a 90° V-twin<br />

without having to throw<br />

crankcases, gearboxes and<br />

internals at it with WSB<br />

regularity, is astonishing. Even<br />

more astonishing is how much<br />

difference there is between this<br />

54<br />

PERFORMANCEBIKES.CO.UK | JUNE 2015

THE RUTTER TEST / S1000RR v R1 v 1299 S<br />

bike and its predecessor.<br />

The 1199 was a bastard of a<br />

handful at speed, especially<br />

away from a racetrack where<br />

bumps, cat’s eyes, potholes and<br />

white lines would blur the rider’s<br />

vision like sitting on a<br />

supercharged Kango hammer. It<br />

had plenty of performance, but<br />

the trick was getting to use it.<br />

Even quality ex-international<br />

racers struggled on track to<br />

match the lap times other bikes<br />

could comfortably set.<br />

On the road, you couldn’t take<br />

the bike anywhere near full<br />

potential because it’d leap about<br />

like a beached mackerel trying<br />

to climb back into the sea.<br />

The 1299 takes that zone<br />

of extreme behaviour<br />

and pushes it 30mph<br />

further away, then<br />

smoothes out the rest<br />

of the ride as if Claudio<br />

Domenicali himself is ironing<br />

out the wrinkles in the road<br />

before you get to them.<br />

The engine feels more<br />

managed than the 1199; softer<br />

edges to the combustion blows,<br />

less driveline chatter, greater rev<br />

range flexibility and more<br />

forgiving suspension. Where the<br />

old bike would charge headlong,<br />

bars flapping and suspension<br />

bucking, the 1299 dips its tail<br />

and gets on with going fast. All<br />

three bikes are physical at speed.<br />

The R1 spends so much time<br />

with its front wheel hovering<br />

serenely a few inches off the<br />

ground you sometimes forget<br />

and only realise when you go to<br />

steer it and you can’t.<br />

The BMW, physically larger<br />

than the R1, takes more muscle<br />

to thread it down a country road.<br />

And the Ducati has the most<br />

chassis movement, moving<br />

about beneath as if to remind<br />

you how fast you’re travelling.<br />

Neither is better nor worse; just<br />

different flavours of fantastical.<br />

Even the 1299’s riding<br />

position feels different from the<br />

1199 (although it’s apparently<br />

almost identical; the fairing nose<br />

is wider, screen taller and seat is<br />

comfier). It all adds up to a<br />

serious degree of usability; the<br />

1299 Panigale S is a Ducati with<br />

manners even a committed<br />

four-cylinder fan can appreciate.<br />

This morning I was convinced I<br />

need an R1 in my life, by midday<br />

the BMW was the only bike for<br />

me... but now, as the shadows<br />

lengthen, it’s the Panigale I can<br />

see in my garage.<br />

As the day draws to a close, we<br />

cruise back to the PB office. At a<br />

leisurely pace, the BMW shines<br />

with its competence and<br />

user-friendliness – until I jump<br />

back on the Ducati and it<br />

becomes my favourite again,<br />

with its lumping great character.<br />

Then I finish on the R1 and<br />

decide no, that’s the engine I’ll<br />

be dreaming about tonight.<br />

Hop on then, I’ll go easy ‘So I grabbed it by the hips and...’ Fast crest = S1000RR launchpad<br />

Öhlins EC<br />

suspension is a<br />

real leap forward<br />

JUNE 2015 | PERFORMANCEBIKES.CO.UK 55

ON THE ROAD<br />

WE’LL TAKE THE RED ONE<br />

Each of these bikes lights our fires in different ways...<br />

THE SUN IS setting, so<br />

we park up to pick a<br />

winner. It’s impossible<br />

of course. Unlike lap<br />

times, dynos and top<br />

speeds, on the road with bikes<br />

like the R1, S1000RR and<br />

Panigale there are no empirical<br />

absolutes. It’s all about opinions<br />

and preferences.<br />

Obviously all three operate at<br />

a stratospheric level of<br />

performance, with handling and<br />

electronics to match. if you’ve<br />

got the money all three of these<br />

bikes unlock an amazing world.<br />

But within that there are<br />

differences and the bikes have<br />

slightly different strengths and<br />

weaknesses. It’s all about what<br />

you want from a bike. So...<br />

IF YOU WANT TO<br />

FEEL LIKE A RACER<br />

The R1 is the race bike of the<br />

bunch; the lightest-feeling<br />

and the most aggressive. You’d<br />

choose it if you wanted to live<br />

on a track and replicate the<br />

feats of Rossi and Lorenzo.<br />

But the engine is perfectly<br />

atuned to road riding, too, and<br />

the handling is brilliant. It’s as<br />

good as Japan gets in 2015.<br />

IF YOU WANT TO<br />

FEEL AMAZED<br />

And amazing, the Ducati is<br />

the best-looking, surprisingly<br />

civilised but still boomingly<br />

domineering. It’s a highly<br />

visible, swaggering statement of<br />

speed – but now packaged with<br />

more finesse, and genuinely fun<br />

instead of terrifying. But it is a<br />

huge amount of money – even<br />

the base model is £17k and this<br />

S model is almost £21k.<br />

IF YOU WANT THE<br />

MOST COMPLETE BIKE<br />

The S1000RR is the most<br />

refined and civilised, with the<br />

most concessions to the niceties<br />

of life. It has huge power, great<br />

handling and an easy-to-expolit<br />

manner than makes you get the<br />

most of of it soonest.<br />

But it’s also the least<br />

engaging, emotionally – the one<br />

motorcycle here that stirs the<br />

soul slightly less.<br />

But, ultimately, Michael<br />

Rutter, John McAvoy and I all<br />

agree. We’d have the red one...<br />

SECOND OPINIONS WHAT WOULD BE YOUR CHOICE AS A ROAD BIKE?<br />

“THE DUCATI IS<br />

your Ferrari on two<br />

wheels; a show<br />

machine. I love the<br />

noise and the looks, but it hasn’t<br />

quite got the performance edge<br />

over the Yamaha.<br />

The BMW is a go-anywhere,<br />

do anything bike, and I’d buy one<br />

if I was planning on doing many<br />

miles. And you could do a lot on<br />

it and not have a problem or<br />

complaint.<br />

“But the R1 is a race bike. It’s<br />

so exciting to ride; it makes your<br />

heart beat faster and you push it<br />

that little bit harder as a result.<br />

You get a real rush from caning<br />

it. You just want to ride it again<br />

and again and the engine is<br />

really, really special. It feels like<br />

it’s worth £15,000 just for that.<br />

“If I had to chose right now<br />

which one to have, it’d definitely<br />

be the R1. It’s a bit of fun, the<br />

engine is incredible. The R1 isn’t<br />

a bike you’d ever get bored of.”<br />

Michael Rutter<br />

“FOR ME, THE<br />

Yamaha is trying a<br />

little bit too hard. It’s<br />

basically Yamaha<br />

catching up with what Ducati and<br />

BMW (and Aprilia) are already<br />

doing. It hasn’t got anything they<br />

haven’t, apart from the<br />

crossplane engine.<br />

“The look and the finish is a bit<br />

rushed, too. It doesn’t look like a<br />

£15,000 motorbike. The Ducati<br />

definitely lets you know where<br />

the money went. It’s pure theatre<br />

– all about the show. Plenty of<br />

go, too, of course, and it’s much<br />

easier to use than the 1199<br />

Panigale. A much nicer bike on<br />

the road.<br />

“I’d have the Ducati as a road<br />

bike. It’s just... silly. Theatre,<br />

noise, riding position. I’d have the<br />

base model, though, without the<br />

fancy suspension; I don’t see the<br />

point for the money. You can do<br />

a huge amount of trackday with<br />

the money you’d save...”<br />

John McAvoy

Kawasaki<br />

ZZ-R1100D<br />

Go far and fast with Kawasaki’s 175mph ZZ-R1100<br />

WE WANT IT<br />

WORDS CHRIS NEWBIGGING PHOTOGRAPHY JASON CRITCHELL<br />

Chris tests the ZZ-R’s<br />

aerodynamic efficiency<br />

70

Desire<br />

Big the ZZ-R might<br />

be but it’s also clever<br />

FOR SALE<br />

£3150<br />

Paddock Hill<br />

Motorcycles (07790<br />

853250 or 01905<br />

776876)<br />

AWASAKI make bikes in all<br />

K<br />

shapes and sizes, but really<br />

they’re at their best with big-bore<br />

sportsbikes. From the very first<br />

Z1, Kawasaki have always been on a quest<br />

for straightline speed on two wheels.<br />

It was entirely logical for them to be the<br />

manufacturer to produce the first ‘hyperbike’.<br />

A conventional big-bore sportsbike is usually<br />

a rounded package, built to go around<br />

corners as well as achieve rocket speed.<br />

Hyperbikes were a different prospect.<br />

The first ZZ-R (1990) was purposely<br />

tailored for high speed – the highest, in fact.<br />

Kawasaki Heavy Industries had won and lost<br />

the title for world’s fastest production bike on<br />

a few occasions, so to make sure they held<br />

the title for a longer stretch, they went all out.<br />

Aerodynamic efficiency was a key part of<br />

the build. Sharp, aggressive race bike fairings<br />

were side-stepped for a smooth, bulbous<br />

design that would gently part the air at the<br />

front and allow the 1052cc machine to slip<br />

through the gap with minimal resistance.<br />

The engine was mostly older proven<br />

technology – the architecture is a derivative<br />

of the GPZ900/1000/ZX-10 lineage. Bigger<br />

cylinders, a downdraught head and carbs and<br />

other improvements helped increase power,<br />

but the big news was Ram-Air.<br />

Ram-Air scoops have an<br />

insatiable appetite<br />

71

Not the quickest around bends<br />

but mad fast between them<br />

Understated and classy<br />

by 1990s’ standards<br />

Plenty of space to settle in<br />

and get comfortable<br />

A snout in the nose fed air into a sealed<br />

airbox, which was designed to increase<br />

power at speed by creating a small amount of<br />

pressure. Peak power was a claimed 145bhp.<br />

Early C-models were voluntarily restricted<br />

to 125bhp from the factory, as manufacturers<br />

worked in anticipation of compulsory power<br />

limits threatened by MEPs. Derestriction was<br />

simple – just modify or fit ZXR750 carb tops<br />

to allow the slides to lift fully – and the<br />

ZZ-R’s immense speed and power made it<br />

king of the road.<br />

And so it would remain until Honda copied<br />

and updated the idea with the Blackbird in<br />

1997. The C1 was initially launched and<br />

aligned with flagship sportsbikes like the<br />

CBR1000F and GSX-R1100, but as<br />

sportsbikes became lighter and more radical,<br />

the ZZ-R found a better fit as a rapid<br />

sports-tourer, a position cemented with the<br />

revised (and unrestricted) D-model in 1993.<br />

Like this stunningly well-kept D7 from<br />

Paddock Hill Bikes. For all the engineering<br />

brilliance, Kawasaki skimped on the finish a<br />

little, so to find one this clean and original<br />

with just 15,000 miles is a treat.<br />

Even if the cosmetics weren’t as good as<br />

they are, you could guess the mileage by the<br />

way it runs. From the first few seconds of<br />

Kawasaki’s excessively high-rpm on-thechoke<br />

running, this one runs with a crisp feel<br />

that isn’t present on ZZ-Rs with worn carbs.<br />

In general, smooth is the theme of the<br />

ZZ-R. If you’re used to hard-edged<br />

Kawasakis with snarling motors and<br />

granite-like damping properties, the<br />

72

Desire<br />

SPECIFICATION<br />

1999 Kawasaki ZZ-R1100D7<br />

ENGINE<br />

Type<br />

liquid-cooled, dohc, 16v<br />

inline-four<br />

Capacity<br />

1052cc<br />

Bore x stroke 76x 58mm<br />

Compression ratio 11:1<br />

Ignition<br />

digital<br />

Carburation 4 x Keihin CVKD40<br />

TRANSMISSION<br />

Primary/final drive chain/chain<br />

Clutch<br />

wet, multiplate<br />

Gearbox<br />

6-speed<br />

CHASSIS<br />

Frame<br />

twin-spar aluminium beam<br />

Front suspension 43mm telescopic, preload and<br />

rebound damping adjustment<br />

Rear suspension Uni-Trak monoshock<br />

Front brake 2 x 320mm discs,<br />

four-piston Tokico calipers<br />

Rear brake 1 x 220mm disc,<br />

opposed-piston caliper<br />

Wheels<br />

3-spoke cast aluminium<br />

Front tyre 120/70-ZR17<br />

Rear tyre<br />

180/55-ZR17<br />

DIMENSIONS<br />

Dry weight 233kg (513lbs)<br />

Wheelbase 1500mm (58.5in)<br />

Seat height 780mm (30.42in)<br />

Fuel capacity 24 litres (5.28 gal)<br />

PERFORMANCE<br />

Top speed 175mph<br />

Power (claimed) 147bhp@10,000rpm<br />

Torque (claimed) 81lb.ft@8500rpm<br />

Fuel consumption 38mpg<br />

Zed-Zed-Arr will surprise you. It’s refined in<br />

every way – comfortable, good ride quality<br />

with easy handling for something that looks<br />

a bit of a whale.<br />

It still has teeth though. Wind the throttle<br />

open from anything above 4000rpm (there’s<br />

a bit of a flatspot just below to pass noise<br />

regs) and the 1052cc motor dishes up more<br />

and more torque. There’s no step in the<br />

power – it just keeps the needles whipping<br />

around the dials relentlessly as the Ram Air<br />

system resonates from the hundreds of litres<br />

of air being pushed through.<br />

Fortunately the days of Z1s bending under<br />

the strain of their own motive power had<br />

long since passed by the time of the ZZ-R.<br />

The twin-spar aluminium frame keeps<br />

everything nicely in check, and although age<br />

has thinned the damping oil, the suspension<br />

doesn’t tie it in a knot either.<br />

It’s all surprisingly manageable – the tank/<br />

seat/peg arrangement gives my six-foot figure<br />

plenty of room to get comfortable without<br />

stretching me out to the point of reduced<br />

feel. It’s still a weighty, soft bike with a long<br />

Fold-out hooks<br />

ready for bungees<br />

Eccentric chain adjuster<br />

for tension and ride height<br />

wheelbase so it’s no scratcher, but with the<br />

new tyres about to be fitted, this ZZ-R will<br />

still be capable of getting through bends as<br />

quickly as it can sprint between them.<br />

The Tokico four-piston brakes are sensitive<br />

to condition, and thankfully this pair are in<br />

good shape, so keeping a lid on speed is no<br />

issue. There’s room for improvement with<br />

new hoses and fluid to replace the originals’<br />

now well-past use-by date.<br />

I could really live with the ZZ-R. The<br />

colour helps – not the most exciting shade,<br />

but it has a classier feel than some of the<br />

more questionable 1990s colour combos<br />

Kawasaki played with. There’s not much you<br />

couldn’t reasonably expect of it, and in years<br />

to come I’m sure that ZZ-Rs will find their<br />

place as classics too, so it’s a thoroughly<br />

useable bike that won’t kick you in the teeth<br />

with depreciation either. This one’s a corker<br />

at a fair price – it won’t be long before it finds<br />

a new owner.<br />

Thanks to Paddock Hill Motorcycles<br />

(07790 853250 or 01905 776876)<br />

The alternatives<br />

1995 Triumph Daytona 1200<br />

Triumph claimed the same power as<br />

the ZZ-R, though in reality it was a<br />

more exaggerated number. Even so,<br />

Hinckley’s 1200-four packs a lot of go,<br />

and this 9000-mile bike looks cheap at<br />

£2550 on eBay.<br />

1996 Honda CBR1100XX<br />

Super Blackbird<br />

The one to usurp the ZZ-R, it’s the<br />

same idea but more so. They’ll handle<br />

miles readily – over a million happily<br />

– but you’ll pay more in like-for-like<br />

condition. This one has done 41,000<br />

miles and is up for £2195 on eBay.<br />

73