Price discrimination - Magazines - philipallan.co.uk

Price discrimination - Magazines - philipallan.co.uk

Price discrimination - Magazines - philipallan.co.uk

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

TOPFOTO<br />

<strong>Price</strong> <strong>discrimination</strong><br />

University tuition fees<br />

William Bohanna discusses whether a university can practise third-degree<br />

price <strong>discrimination</strong> with the new fee structure<br />

There has been much <strong>co</strong>ntroversy over<br />

the government’s plans to lift the cap on<br />

university tuition fees. Ministers have voted<br />

to allow universities in England to charge<br />

tuition fees up to £9,000 per year. Following<br />

re<strong>co</strong>mmendations by Lord Browne — who<br />

led the independent review of higher education<br />

funding — this measure <strong>co</strong>mes in light<br />

of budget cuts to aid the national e<strong>co</strong>nomy<br />

and UK budget deficit. However, has the<br />

government made the market for university<br />

education more accessible to practise thirddegree<br />

price <strong>discrimination</strong>?<br />

As e<strong>co</strong>nomics students, it is always good<br />

to question the way in which price <strong>discrimination</strong><br />

can be carried out in various<br />

markets, and as such whether the market<br />

for higher education <strong>co</strong>uld practise price<br />

<strong>discrimination</strong>.<br />

What is price <strong>discrimination</strong>?<br />

When a firm has power over a market (a<br />

degree of monopoly power), it may be able<br />

to increase its total profits by charging different<br />

prices for the same good or service<br />

in different markets. This is known as price<br />

P<br />

a<br />

p<br />

0<br />

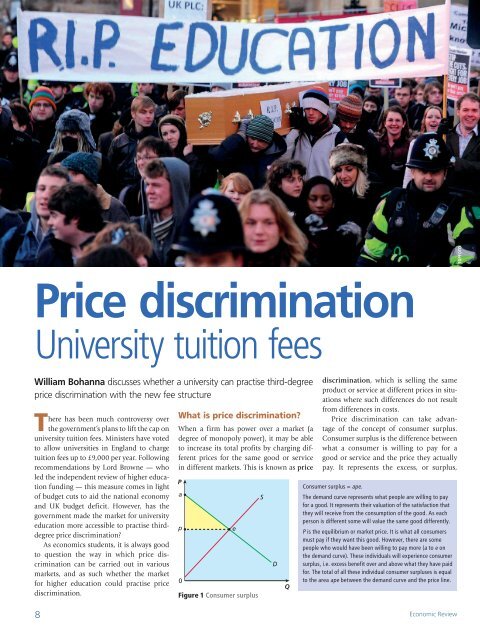

Figure 1 Consumer surplus<br />

e<br />

S<br />

D<br />

Q<br />

<strong>discrimination</strong>, which is selling the same<br />

product or service at different prices in situations<br />

where such differences do not result<br />

from differences in <strong>co</strong>sts.<br />

<strong>Price</strong> <strong>discrimination</strong> can take advantage<br />

of the <strong>co</strong>ncept of <strong>co</strong>nsumer surplus.<br />

Consumer surplus is the difference between<br />

what a <strong>co</strong>nsumer is willing to pay for a<br />

good or service and the price they actually<br />

pay. It represents the excess, or surplus,<br />

Consumer surplus = ape.<br />

The demand curve represents what people are willing to pay<br />

for a good. It represents their valuation of the satisfaction that<br />

they will receive from the <strong>co</strong>nsumption of the good. As each<br />

person is different some will value the same good differently.<br />

P is the equilibrium or market price. It is what all <strong>co</strong>nsumers<br />

must pay if they want this good. However, there are some<br />

people who would have been willing to pay more (a to e on<br />

the demand curve). These individuals will experience <strong>co</strong>nsumer<br />

surplus, i.e. excess benefit over and above what they have paid<br />

for. The total of all these individual <strong>co</strong>nsumer surpluses is equal<br />

to the area ape between the demand curve and the price line.<br />

8 E<strong>co</strong>nomic Review

P<br />

Q 2<br />

0<br />

Q 1<br />

Q<br />

Where one price is charged (P 1<br />

):<br />

a<br />

Consumer surplus is P 1<br />

ab<br />

Revenue is 0P 1<br />

bq 1<br />

P 2<br />

c<br />

When price <strong>discrimination</strong> occurs (P 1<br />

and P 2<br />

prices):<br />

Consumer surplus is P 2<br />

ac (P 2<br />

) and ceb (P 1<br />

)<br />

P 1<br />

e b<br />

Revenue is 0P 2<br />

cQ 2<br />

(P 2<br />

) and Q 2<br />

ebQ 1<br />

(P 1<br />

)<br />

D<br />

Figure 2 <strong>Price</strong> <strong>discrimination</strong><br />

satisfaction derived from the purchase over<br />

and above what has been paid for (Figure 1).<br />

<strong>Price</strong> <strong>discrimination</strong> occurs due to the<br />

downward sloping nature of the demand<br />

curve — there are always some people who<br />

are willing to pay more for a good or service<br />

than others.<br />

Firms tend to charge one price — the<br />

equilibrium price. As a result, a lot of people<br />

buy goods and services at prices below that<br />

which they are willing to pay. <strong>Price</strong> <strong>discrimination</strong><br />

is a method that firms use to appropriate<br />

all or part of this <strong>co</strong>nsumer surplus in<br />

the form of revenue.<br />

Figure 2 shows how the practice of price<br />

<strong>discrimination</strong> allows for an increase in<br />

revenue of the price discriminator and an<br />

appropriation of <strong>co</strong>nsumer surplus. Any<br />

private sector firm would enjoy this situation,<br />

as the potential for increasing profits<br />

is very motivating. This <strong>co</strong>uld readdress the<br />

funding problems that struggling universities<br />

have faced for many years.<br />

Ac<strong>co</strong>rding to theory, there are three levels<br />

of price <strong>discrimination</strong> that a firm <strong>co</strong>uld<br />

follow.<br />

First-degree price <strong>discrimination</strong>: this<br />

is where firms persuade all <strong>co</strong>nsumers in the<br />

market to reveal the price they are willing to<br />

pay. Here, the firm would be appropriating<br />

the entire <strong>co</strong>nsumer surplus — by looking<br />

at the particular point on the demand curve<br />

<strong>co</strong>rresponding to each individual. This<br />

<strong>co</strong>uld not be used in the higher education<br />

market, as it would mean each student effectively<br />

bidding for their place. This would be<br />

time <strong>co</strong>nsuming and would favour richer<br />

students, so it tends to occur only where the<br />

market is very small — sealed bid auctions,<br />

for example.<br />

Se<strong>co</strong>nd-degree price <strong>discrimination</strong>:<br />

this is where the firm sells different quantities<br />

of a good at different prices to the same<br />

<strong>co</strong>nsumer. Or, <strong>co</strong>nsumers pay different<br />

September 2011<br />

prices based on their <strong>co</strong>nsumption level.<br />

This <strong>co</strong>uld not occur in the higher education<br />

market because the quantities for a degree<br />

are roughly the same, but it does occur in<br />

energy markets — high-level <strong>co</strong>nsumers,<br />

such as firms, may be charged different<br />

prices per unit <strong>co</strong>mpared to small users,<br />

such as households.<br />

Third-degree price <strong>discrimination</strong>: this<br />

is where the firm sells identical products at<br />

different prices to different groups of <strong>co</strong>nsumers<br />

(known as market segments). The<br />

following list shows how a market can be<br />

segmented:<br />

■■<br />

Time — peak and off-peak prices<br />

(airlines and rail <strong>co</strong>mpanies)<br />

■■<br />

Age — lower fares for children, students<br />

and OAPs on buses and trains<br />

■■<br />

Location — bus <strong>co</strong>mpanies often charge<br />

different prices in different parts of the<br />

<strong>co</strong>untry<br />

■■<br />

In<strong>co</strong>me — people on low in<strong>co</strong>mes can<br />

often get <strong>co</strong>ncessionary fares<br />

Practising price <strong>discrimination</strong><br />

Could the higher education market practise<br />

third-degree price <strong>discrimination</strong> if it met<br />

certain <strong>co</strong>nditions? There are four <strong>co</strong>nditions<br />

that must be met for third-degree price<br />

<strong>discrimination</strong> to occur:<br />

1 The firm must be a monopolist — if there<br />

are other firms in the market then they can<br />

undercut the high price and take away customers<br />

from the price discriminator.<br />

2 The monopolist must be able to split<br />

the market into easily distinguishable and<br />

distinct groups of buyers, otherwise how<br />

can it tell who is willing to pay a high or a<br />

low price?<br />

3 The monopolist must be able to keep<br />

the market segments separate at a relatively<br />

low <strong>co</strong>st. This avoids arbitrage — where<br />

buyers in low-priced segments undercut the<br />

monopolist by reselling the product in the<br />

high-price segment at a lower price. If the<br />

<strong>co</strong>sts of keeping the markets separate are<br />

high then this will negate the extra revenue<br />

earned from the high-priced segment.<br />

4 Each market segment must face different<br />

demand curves, i.e. the elasticity of the<br />

buyers must differ — if it were the same the<br />

monopolist <strong>co</strong>uld not charge different prices.<br />

For a university to practise third-degree<br />

price <strong>discrimination</strong>, these <strong>co</strong>nditions must<br />

be met.<br />

Meeting the <strong>co</strong>nditions<br />

1 The university as a monopolist? The<br />

university offering degree programmes from<br />

their institution is effectively a monopolist<br />

for that set of degree programmes, as no<br />

other university can offer this degree from<br />

this institution. Therefore, the university<br />

has monopoly power over its degree programmes.<br />

Other universities will be offering<br />

similar <strong>co</strong>urses but if you want to do the<br />

degree at a certain university then you have<br />

no choice, and as such the university has<br />

gained a monopoly power.<br />

2 Can the university split the market<br />

into distinct groups of buyers? The<br />

answer to this <strong>co</strong>ndition effectively occurs in<br />

the UCAS application system. For example,<br />

a university <strong>co</strong>uld offer an e<strong>co</strong>nomics with<br />

mathematics degree and an e<strong>co</strong>nomics with<br />

Latin American studies degree. Depending<br />

on the number of applicants that each<br />

degree <strong>co</strong>urse attracts, the university has two<br />

groups of buyers. Therefore, the university<br />

can easily split the market and applicants<br />

into distinct groups of buyers: e<strong>co</strong>nomics<br />

with mathematics applicants and e<strong>co</strong>nomics<br />

with Latin American studies applicants. This<br />

means that the university has two groups of<br />

buyers for a degree from their university.<br />

3 Can the university keep the different<br />

market segments separate at a relatively<br />

low <strong>co</strong>st? Again the answer to this <strong>co</strong>ndition<br />

occurs in the UCAS application system.<br />

As this is an online system, the university<br />

can keep these two markets of e<strong>co</strong>nomics<br />

with mathematics applicants and e<strong>co</strong>nomics<br />

with Latin American studies applicants<br />

separate at little or no <strong>co</strong>st because this<br />

market does not interact on a face-to-face<br />

level, and <strong>co</strong>vers the whole globe in terms of<br />

applications.<br />

4 Does each market segment face<br />

different demand curves? Effectively yes,<br />

if we assume that we have the two different<br />

markets for degree programmes at a<br />

university of e<strong>co</strong>nomics with mathematics<br />

9

ZOE/FOTOliA<br />

Rail travel is subject to third-degree price<br />

<strong>discrimination</strong><br />

applicants and e<strong>co</strong>nomics with Latin<br />

American studies applicants, then it would<br />

be fair to say that each market segment<br />

<strong>co</strong>uld face a different elasticity of demand.<br />

E<strong>co</strong>nomics with Latin American studies<br />

applicants face inelastic price elasticity of<br />

demand (PED) (due to this being a more<br />

unique <strong>co</strong>mbination with a fewer amount of<br />

substitutes) and the e<strong>co</strong>nomics with mathematics<br />

applicants face a relatively elastic<br />

PED (due to this being a more <strong>co</strong>mmon<br />

<strong>co</strong>mbination with a large amount of substitutes).<br />

How would this work?<br />

Let us assume a monopolist at a particular<br />

university (Figure 3). There are two clearly<br />

definable market segments:<br />

E<strong>co</strong>nomics and<br />

mathematics applicants<br />

■■<br />

E<strong>co</strong>nomics with Latin American studies<br />

applicants. This will have inelastic PED.<br />

■■<br />

E<strong>co</strong>nomics with mathematics applicants.<br />

This will have elastic PED.<br />

The segments are easy to keep apart, as<br />

it is difficult to transfer or change an applicant’s<br />

preference for a university place.<br />

For each segment we can identify the<br />

demand curve (AR) and therefore the MR<br />

curve. If the two segments were aggregated,<br />

then the market demand curve would be<br />

produced. On the market diagram, we can<br />

draw the <strong>co</strong>st curves — which are the same<br />

in each market segment (by definition price<br />

<strong>discrimination</strong> does not arise due to <strong>co</strong>st<br />

differences).<br />

The university maximises profits at Q M<br />

where MC=MR. If the university was to<br />

E<strong>co</strong>nomics and Latin American<br />

studies applicants<br />

charge a single price, marginal revenue<br />

would be lower for e<strong>co</strong>nomics with Latin<br />

American studies than for e<strong>co</strong>nomics with<br />

mathematics, so it would increase profits<br />

if the university was to charge a higher<br />

price (P P<br />

) and take fewer e<strong>co</strong>nomics with<br />

Latin American studies applicants and take<br />

more mathematics applicants at a lower<br />

price (P O<br />

) where MR is equalised for the<br />

two groups. This would be with Q o<br />

mathematics<br />

and Q P<br />

Latin American applicants.<br />

Notice that:<br />

Q M<br />

= Q O<br />

+ Q P<br />

If we extend the line showing the output<br />

level in each segment up to the AR or D<br />

curve, then we can read off the price for that<br />

segment. Notice the e<strong>co</strong>nomics with Latin<br />

American studies applicants segment has<br />

Total market<br />

<strong>Price</strong><br />

Supernormal profits<br />

<strong>Price</strong><br />

<strong>Price</strong><br />

MC<br />

AC<br />

P P<br />

P O<br />

AC<br />

MR<br />

MR O<br />

AR O<br />

MR<br />

AR P<br />

MR<br />

AR<br />

Q O<br />

Quantity of places<br />

Q P<br />

Quantity of places<br />

Q M<br />

Quantity of places<br />

Figure 3 <strong>Price</strong> <strong>discrimination</strong> with two market segments<br />

10 E<strong>co</strong>nomic Review

higher prices (and more inelastic demand)<br />

than the e<strong>co</strong>nomics with mathematics<br />

applicants segment.<br />

The line showing the level of AC can also<br />

be extended across the segments, as by definition<br />

price <strong>discrimination</strong> does not arise<br />

due to <strong>co</strong>st differences. From this we can<br />

determine the level of supernormal profits<br />

in each segment.<br />

If the elasticities were the same in each<br />

segment the demand (AR) curves would<br />

be the same and therefore MR, prices and<br />

profits would also be the same.<br />

Conclusion<br />

By reviewing these <strong>co</strong>nditions, it would be<br />

possible for a university to practise thirddegree<br />

price <strong>discrimination</strong>. However,<br />

the government has stated that in order<br />

for a university to charge a higher price it<br />

must meet certain <strong>co</strong>nditions. Universities<br />

wanting to charge more than £6,000 would<br />

have to undertake measures — such as<br />

offering bursaries, summer schools and<br />

outreach programmes — to en<strong>co</strong>urage<br />

students from poorer backgrounds to apply.<br />

Therefore, this would alter the nature of the<br />

degree <strong>co</strong>urse and so would differentiate the<br />

service and not meet the definition of price<br />

<strong>discrimination</strong>.<br />

In addition, there is the central problem<br />

of university fees being inequitable for<br />

poorer students and universities minister<br />

David Willetts has said that universities will<br />

only be allowed to charge fees of £9,000 in<br />

‘exceptional circumstances’, for example if<br />

they had high teaching <strong>co</strong>sts or if they were<br />

offering an intensive 2-year <strong>co</strong>urse.<br />

Universities charging more than £6,000<br />

will have to <strong>co</strong>mmit to ‘access agreements’,<br />

negotiated with the Office For Fair Access<br />

(Offa), to <strong>co</strong>mmit them to programmes to<br />

recruit students from poorer backgrounds.<br />

Therefore, the final answer to the question<br />

of whether a university <strong>co</strong>uld practise<br />

price <strong>discrimination</strong> is quite simply no,<br />

but this does not mean that they would not<br />

want to. The age-old problem facing universities<br />

and the government is that demand for<br />

university places outreaches supply causing<br />

a shortage, so perhaps these increased fees<br />

are a way of dealing with that shortage in<br />

order to reduce demand? Either way, universities<br />

will not be able to take advantage of<br />

this measure in the form of price <strong>discrimination</strong><br />

and its revenue generating benefits.<br />

Review notes<br />

1 The new system for funding higher<br />

education through student tuition fees<br />

has caused widespread <strong>co</strong>nsternation and<br />

<strong>co</strong>ntroversy.<br />

2 <strong>Price</strong> <strong>discrimination</strong> can take place in<br />

markets that have certain characteristics. It<br />

involves setting different prices to different<br />

<strong>co</strong>nsumers for what is substantially the<br />

same product.<br />

3 Firms that practise price <strong>discrimination</strong><br />

are able to increase their profits at the<br />

expense of <strong>co</strong>nsumer surplus.<br />

4 There are different levels of price<br />

<strong>discrimination</strong> possible, depending on the<br />

characteristics of the market.<br />

5 If the price elasticity of demand differs<br />

for some university programmes then there<br />

may be s<strong>co</strong>pe for price <strong>discrimination</strong> to<br />

be used, although the <strong>co</strong>nditions imposed<br />

on universities wanting to charge a price<br />

above £6,000 may make it more difficult to<br />

implement.<br />

See E<strong>co</strong>nomicReviewOnline for an<br />

update on this market and a video<br />

relating to Figure 3. £<br />

William Bohanna is head of e<strong>co</strong>nomics and<br />

business studies at the British School of Brussels.<br />

Instant revision…<br />

just when you need it<br />

●<br />

●<br />

100s of quick-fire questions and answers<br />

Exam tips to understand and memorise key topics<br />

●<br />

Fits in your pocket for instant revision, wherever<br />

and whenever you need it!<br />

£4.99<br />

Just £3.99 with your 20% off voucher<br />

(see September issue)<br />

Visit www.<strong>philipallan</strong>.<strong>co</strong>.<strong>uk</strong> today for information on all<br />

the titles in the series and simple online ordering, or <strong>co</strong>ntact<br />

our customer services department on 01235 827827<br />

September 2011<br />

11