Four-circle Hevajra Mandala - Reflections of the Buddha

Four-circle Hevajra Mandala - Reflections of the Buddha

Four-circle Hevajra Mandala - Reflections of the Buddha

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

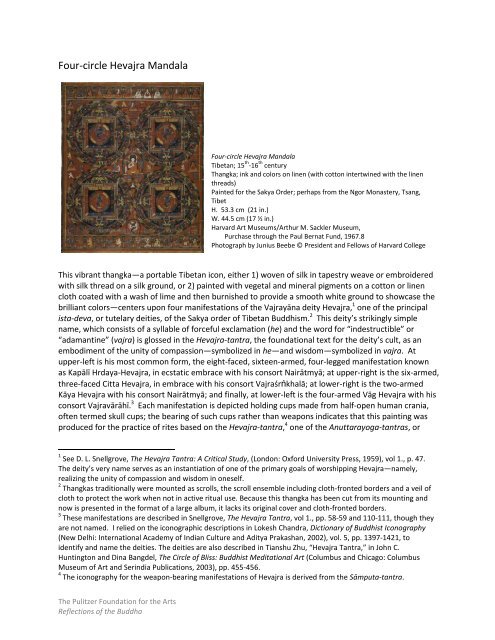

<strong>Four</strong>-<strong>circle</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> <strong>Mandala</strong><br />

<strong>Four</strong>-<strong>circle</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> <strong>Mandala</strong><br />

Tibetan; 15 th -16 th century<br />

Thangka; ink and colors on linen (with cotton intertwined with <strong>the</strong> linen<br />

threads)<br />

Painted for <strong>the</strong> Sakya Order; perhaps from <strong>the</strong> Ngor Monastery, Tsang,<br />

Tibet<br />

H. 53.3 cm (21 in.)<br />

W. 44.5 cm (17 ½ in.)<br />

Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum,<br />

Purchase through <strong>the</strong> Paul Bernat Fund, 1967.8<br />

Photograph by Junius Beebe © President and Fellows <strong>of</strong> Harvard College<br />

This vibrant thangka—a portable Tibetan icon, ei<strong>the</strong>r 1) woven <strong>of</strong> silk in tapestry weave or embroidered<br />

with silk thread on a silk ground, or 2) painted with vegetal and mineral pigments on a cotton or linen<br />

cloth coated with a wash <strong>of</strong> lime and <strong>the</strong>n burnished to provide a smooth white ground to showcase <strong>the</strong><br />

brilliant colors—centers upon four manifestations <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Vajrayāna deity <strong>Hevajra</strong>, 1 one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> principal<br />

ista-deva, or tutelary deities, <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sakya order <strong>of</strong> Tibetan Buddhism. 2 This deity’s strikingly simple<br />

name, which consists <strong>of</strong> a syllable <strong>of</strong> forceful exclamation (he) and <strong>the</strong> word for “indestructible” or<br />

“adamantine” (vajra) is glossed in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong>-tantra, <strong>the</strong> foundational text for <strong>the</strong> deity’s cult, as an<br />

embodiment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> unity <strong>of</strong> compassion—symbolized in he—and wisdom—symbolized in vajra. At<br />

upper-left is his most common form, <strong>the</strong> eight-faced, sixteen-armed, four-legged manifestation known<br />

as Kapālī Hrdaya-<strong>Hevajra</strong>, in ecstatic embrace with his consort Nairātmyā; at upper-right is <strong>the</strong> six-armed,<br />

three-faced Citta <strong>Hevajra</strong>, in embrace with his consort Vajraśrṅkhalā; at lower-right is <strong>the</strong> two-armed<br />

Kāya <strong>Hevajra</strong> with his consort Nairātmyā; and finally, at lower-left is <strong>the</strong> four-armed Vāg <strong>Hevajra</strong> with his<br />

consort Vajravārāhī. 3 Each manifestation is depicted holding cups made from half-open human crania,<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten termed skull cups; <strong>the</strong> bearing <strong>of</strong> such cups ra<strong>the</strong>r than weapons indicates that this painting was<br />

produced for <strong>the</strong> practice <strong>of</strong> rites based on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong>-tantra, 4 one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Anuttarayoga-tantras, or<br />

1 See D. L. Snellgrove, The <strong>Hevajra</strong> Tantra: A Critical Study, (London: Oxford University Press, 1959), vol 1., p. 47.<br />

The deity’s very name serves as an instantiation <strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> primary goals <strong>of</strong> worshipping <strong>Hevajra</strong>—namely,<br />

realizing <strong>the</strong> unity <strong>of</strong> compassion and wisdom in oneself.<br />

2 Thangkas traditionally were mounted as scrolls, <strong>the</strong> scroll ensemble including cloth-fronted borders and a veil <strong>of</strong><br />

cloth to protect <strong>the</strong> work when not in active ritual use. Because this thangka has been cut from its mounting and<br />

now is presented in <strong>the</strong> format <strong>of</strong> a large album, it lacks its original cover and cloth-fronted borders.<br />

3 These manifestations are described in Snellgrove, The <strong>Hevajra</strong> Tantra, vol 1., pp. 58-59 and 110-111, though <strong>the</strong>y<br />

are not named. I relied on <strong>the</strong> iconographic descriptions in Lokesh Chandra, Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Buddhist Iconography<br />

(New Delhi: International Academy <strong>of</strong> Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan, 2002), vol. 5, pp. 1397-1421, to<br />

identify and name <strong>the</strong> deities. The deities are also described in Tianshu Zhu, “<strong>Hevajra</strong> Tantra,” in John C.<br />

Huntington and Dina Bangdel, The Circle <strong>of</strong> Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art (Columbus and Chicago: Columbus<br />

Museum <strong>of</strong> Art and Serindia Publications, 2003), pp. 455-456.<br />

4 The iconography for <strong>the</strong> weapon-bearing manifestations <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> is derived from <strong>the</strong> Sāmputa-tantra.<br />

The Pulitzer Foundation for <strong>the</strong> Arts<br />

<strong>Reflections</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>

<strong>Four</strong>-<strong>circle</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> <strong>Mandala</strong> 2<br />

“Highest Yoga Tantras,” <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sakya school. The Highest Yoga Tantras are one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> four types <strong>of</strong><br />

tantras in Vajrayāna Buddhism, 5 <strong>the</strong> tantras being systems <strong>of</strong> practice, usually based on specific texts,<br />

that are meant to enable <strong>the</strong> practitioner to attain <strong>Buddha</strong>hood through meditative engagement with a<br />

particular tutelary deity. The Highest Yoga Tantras are believed to allow attainment <strong>of</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>hood in a<br />

single lifetime. They demand that <strong>the</strong> practitioner follow a teacher’s instructions in performing radical<br />

inner transformations—for example, visualizing his body as a particular arrangement <strong>of</strong> deities both<br />

male and female, and fur<strong>the</strong>r visualizing himself as nei<strong>the</strong>r different from nor <strong>the</strong> same as those deities.<br />

These tantras particularly emphasize <strong>the</strong> simultaneous unity <strong>of</strong> and difference between wisdom and<br />

compassion. Because wisdom is considered a female attribute in Buddhist thought and compassion a<br />

male attribute, sexual metaphors and imagery are used extensively. In contemplating such metaphors<br />

and imagery, “desire is converted to bliss, hatred to radiance, and delusion to awareness, and <strong>the</strong> union<br />

<strong>of</strong> male and female is transformed into <strong>the</strong> nondual state <strong>of</strong> compassion and wisdom <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Buddha</strong>.” 6<br />

Importantly, as can be seen in this thankga, <strong>the</strong> deities depicted in ecstatic, sexual embrace are<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>oundly wrathful ones. They all bear various weapons, some trample upon corpses, and o<strong>the</strong>rs wear<br />

garlands <strong>of</strong> skulls. Vajrayāna practitioners understand <strong>the</strong> fearsome appearance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se deities to be,<br />

in fact, an outward manifestation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir compassion. By directing <strong>the</strong>ir wrath against <strong>the</strong> obstacles<br />

that hinder worshippers’ progress along <strong>the</strong> path to awakening, <strong>the</strong>se deities display <strong>the</strong>ir compassion<br />

for <strong>the</strong>ir followers. They manifest, in essence, “benevolent wrath.” 7<br />

These four manifestations <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> are depicted at <strong>the</strong> center <strong>of</strong> a mandala—an array <strong>of</strong> deities<br />

positioned within a palace-like architectural setting, meant to be envisioned as a fully three-dimensional<br />

space. <strong>Mandala</strong>s are usually created in accompaniment to meditative practices in which <strong>the</strong> practitioner<br />

visualizes himself in union with—or as—those deities. 8 While <strong>the</strong> deities depicted within a mandala may<br />

vary, and while stylistic differences may always be identified, <strong>the</strong> basic structure <strong>of</strong> mandalic<br />

compositions remains generally constant across all periods and places <strong>of</strong> Vajrayāna Buddhism. The<br />

structure <strong>of</strong> each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> four mandalas depicted on this thangka might be best understood by taking a<br />

5 The four types are Kriyā-tantra (Action Tantra), Caryā-tantra (Performance Tantra), Yoga-tantra (Yoga Tantra),<br />

and Anuttarayoga-tantra (Highest Yoga Tantra). A brief introduction to <strong>the</strong> different types <strong>of</strong> tantras may be<br />

found in Dina Bangdel and Aviana P. Maki, “Related Esoteric Tantras,” in Huntington and Bangdel, pp. 422-423.<br />

6 Ibid., p. 423.<br />

7 For more on <strong>the</strong> notion <strong>of</strong> “benevolently wrathful” deities, see Rob Linro<strong>the</strong>, “Protection, Benefaction, and<br />

Transformation: Wrathful Deities in Himalayan Art,” in Rob Linro<strong>the</strong> and Jeff Watt, Demonic Divine: Himalayan Art<br />

and Beyond (New York: Rubin Museum <strong>of</strong> Art, 2004), pp. 3-43.<br />

8 <strong>Mandala</strong>s are <strong>of</strong>ten described as “visualization (or meditation) aids.” The texts that prescribe <strong>the</strong> creation <strong>of</strong><br />

mandalas, however, never explicitly describe how <strong>the</strong> worshipper is to interact with mandala, even though such<br />

texts <strong>of</strong>ten tell <strong>the</strong> worshipper to create a physical mandala according to precise instructions and <strong>the</strong>n to construct<br />

an identical mandala in his mind. Thus, while <strong>the</strong> creation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> physical mandala may help practitioners to<br />

familiarize <strong>the</strong>mselves with <strong>the</strong> deities that <strong>the</strong>y envision during meditative practice and to focus <strong>the</strong>ir mind on<br />

those deities, it cannot be asserted with absolute certainty that a mandala is explicitly used during actual<br />

meditative practice. This is not to say that physical mandalas do not serve any precise ritual faction. Indeed,<br />

during some consecration rites (Sanskrit: abhiseka), a mandala may be laid out on a raised altar, onto whose<br />

deities each new initiate into <strong>the</strong> practices associated with <strong>the</strong> mandala tosses a flower petal, taking as his tutelary<br />

deity <strong>the</strong> figure onto which <strong>the</strong> flower petal falls. The Kamakura-period (1185-1333) Womb World <strong>Mandala</strong> also<br />

on display in “<strong>Reflections</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>” could have been used in such a way, though as David Snellgrove points<br />

out, given that mandalas like this <strong>Four</strong>-Circle <strong>Hevajra</strong> <strong>Mandala</strong> focus on only a single presiding deity, it is unlikely<br />

that <strong>the</strong>y would have been used in a similar consecration ritual. See David Snellgrove, Indo-Tibetan Buddhism:<br />

Indian Buddhists and Their Tibetan Successors (Boston: Shambhala, 2002), p. 180.<br />

The Pulitzer Foundation for <strong>the</strong> Arts<br />

<strong>Reflections</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>

<strong>Four</strong>-<strong>circle</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> <strong>Mandala</strong> 3<br />

narrative approach to <strong>the</strong>m, following <strong>the</strong> lead set by worshippers whose visualization practices involve<br />

<strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> mandalic configurations.<br />

We should first imagine approaching one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> four circular mandalas from outside its outermost<br />

boundary. We thus first encounter a wall <strong>of</strong> five-colored flames (red, blue, yellow, white, and green),<br />

here rendered in almost vegetal or foliate manner, which serves as <strong>the</strong> first marker <strong>of</strong> our entry into a<br />

more sacred realm. This sacred realm is fur<strong>the</strong>r sealed within <strong>the</strong> wall <strong>of</strong> flames by a narrow red band,<br />

within which are rendered in gold very schematic vajras—hand-held ritual implements, derived from<br />

ancient Indian weapons, with sharp, curved prongs at each end. Although depicted as a flat band <strong>of</strong><br />

colorful, scrolling forms, and although juxtaposed with o<strong>the</strong>r flat zones <strong>of</strong> decoratively enlivened color,<br />

this seemingly flat representation <strong>of</strong> flames is to be imagined as a vertical, three-dimensional form;<br />

conversely, <strong>the</strong> surrounding bands, including that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> vajra belt, may be read as top-down<br />

topographic representations. This juxtaposition <strong>of</strong> contrasting modes <strong>of</strong> representation is typical <strong>of</strong><br />

mandalas and <strong>of</strong> pre-modern maps more generally.<br />

The first zone within <strong>the</strong> circular vajra belt is occupied by <strong>the</strong> eight charnel grounds (Sanskrit: śmaśāna),<br />

terrifying places for <strong>the</strong> contemplation <strong>of</strong> terrifying, wrathful deities. Each is governed at its center by a<br />

particular deity, who is surrounded by attendants, impaled bodies, corpse-devouring animals, funerary<br />

pyres, and mortuary stūpas—a type <strong>of</strong> Indian funerary monument consisting, in its simplest form, <strong>of</strong> a<br />

semi-spherical mound surmounted by an umbrella, constructed to enshrine <strong>the</strong> remains <strong>of</strong> a particularly<br />

honored person, especially religious leaders like <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong> Śākyamuni. In multiple passages in <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Hevajra</strong>-tantra, such disturbing sites are specified as <strong>the</strong> appropriate place for contemplation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

wrathful <strong>Hevajra</strong>; fur<strong>the</strong>r, it is even specified that <strong>the</strong> colors used in painting his mandala be made from<br />

things like “charcoal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cemetery,” “ground human bones,” and “cemetery bricks,” while a certain<br />

drawing aid is to be made <strong>of</strong> “cemetery thread”—actually, “a thread made from <strong>the</strong> guts <strong>of</strong> a corpse.” 9<br />

Bordering <strong>the</strong> charnel grounds, which are represented as though <strong>the</strong> viewer were standing among <strong>the</strong><br />

figures depicted, are a series <strong>of</strong> multi-colored lotus petals viewed from above, thus signaling our<br />

stepping slightly upward. With this ascent, we come to stand on <strong>the</strong> same plane as <strong>the</strong> palace <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

manifestation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> himself, a structure that assumes a square form. Each wall <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> palace is<br />

depicted as though viewed in pr<strong>of</strong>ile, and each is pierced at its center by an elaborate gate, composed <strong>of</strong><br />

four horizontal slabs—colored, from bottom to top, red, blue, green, and gold—supported by two<br />

columns on each side; <strong>the</strong> form seems to be vaguely inspired by that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> torana, an elaborate postand-lintel<br />

gateway <strong>of</strong>ten placed around a stūpa at each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> four directions. A trefoil arch adorns <strong>the</strong><br />

front face <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> slabs, which are surmounted by a small stūpa-like form bordered on each side by<br />

kneeling deer. The gates are bordered on each side by <strong>the</strong> gaping mouths <strong>of</strong> red makaras, hybrid sea<br />

monsters seen throughout pan-Asian Buddhist sites as gate protectors. From <strong>the</strong>ir mouths spew vivid<br />

foliage, colored appropriately to <strong>the</strong> direction that <strong>the</strong>y guard; hence, at top we see yellow foliage,<br />

indicating <strong>the</strong> west; at right, <strong>the</strong> green <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> north; at bottom, <strong>the</strong> bluish-black <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> east; and at left,<br />

9 Snellgrove, The <strong>Hevajra</strong> Tantra, vol. 1., p. 51. Although <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong>-tantra frequently refers to cemeteries, it<br />

does not precisely describe <strong>the</strong> eight cemeteries depicted in mandalas such as this. It seems that it is only in<br />

commentarial literature that <strong>the</strong>y are more fully described. See <strong>the</strong> discussion <strong>of</strong> charnel grounds in “Himalayan<br />

Art,” a major online database <strong>of</strong> Himalayan Buddhist painting and related iconographic information maintained by<br />

<strong>the</strong> Rubin Museum <strong>of</strong> Art in New York (“Subject: Charnel Grounds & Cemeteries,” n.d., ). See also Jeff Watt, “<strong>Mandala</strong>s and <strong>the</strong> Eight Mahasiddhas,” August 2009 <<br />

http://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=2106>.<br />

The Pulitzer Foundation for <strong>the</strong> Arts<br />

<strong>Reflections</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>

<strong>Four</strong>-<strong>circle</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> <strong>Mandala</strong> 4<br />

<strong>the</strong> red <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> south. 10 The directionality <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> color scheme employed in a thangka may give some<br />

indication <strong>of</strong> how it was originally hung in a monastic space. 11<br />

Within <strong>the</strong> gates lies a narrow red band running along <strong>the</strong> four sides <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> palace, on which are<br />

depicted tiny, seated figures, whom I have yet to identify. This narrow band is followed by a much<br />

broader, foliated band, colored again in accordance with <strong>the</strong> four directions. On this band may be found<br />

eight dakinīs (also called, more generically, yoginīs—that is female practitioners <strong>of</strong> yoga), female<br />

attendants to <strong>Hevajra</strong>, who dance atop corpses lying upon red lotuses. These female deities are all<br />

specifically named and described in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong>-tantra. 12 Interspersed among <strong>the</strong>m are vases, common<br />

accoutrements to consecratory rituals. Finally, at <strong>the</strong> center <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> palace, <strong>the</strong> manifestation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong><br />

himself stands atop a lotus pedestal, again rendered from a top-down view, thus indicating <strong>the</strong> deity’s<br />

occupying <strong>the</strong> highest point <strong>of</strong> this generally pyramidal mandala. Each manifestation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> is<br />

depicted in <strong>the</strong> ardha-paryaṅka pose, dancing atop one or more corpses. The four legs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sixteenarmed<br />

Hrdaya-<strong>Hevajra</strong>, for example, trample four corpses, understood to signify <strong>the</strong> four Māras, or<br />

demonic obstructions, to one’s progress on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>’s path. 13<br />

10 For <strong>the</strong> correlation between colors and directions in <strong>Hevajra</strong> mandalas, see Zhu, “<strong>Hevajra</strong> Tantra,” in Huntington<br />

and Bangdel, pp. 454-456, and Catalog Entry #143, “<strong>Hevajra</strong> <strong>Mandala</strong>,” in ibid., pp. 461-464. This correlation is<br />

somewhat different from <strong>the</strong> more common system based on <strong>the</strong> Five Wisdom (or Jina) <strong>Buddha</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Vajradhātu<br />

(Diamond World), each <strong>of</strong> whom symbolizes a particular aspect <strong>of</strong> enlightenment. This system identifies red with<br />

Amitābha, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> West; green with Amoghasiddhi, <strong>Buddha</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> North; blue with Aksobhya, <strong>Buddha</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> East; yellow with Ratnasambhava, <strong>Buddha</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> South; and white with Vairocana, <strong>the</strong> Cosmic <strong>Buddha</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Center. For more on this system, see Amy M. Livingston, “Goal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Transformed Mind: Enlightenment<br />

Symbolized,” in ibid., pp. 90-92. <strong>Mandala</strong>s based on o<strong>the</strong>r tantras make use <strong>of</strong> yet o<strong>the</strong>r correlative systems;<br />

Kalachakra mandalas, for example, identify blue with east, red with south, yellow with west, white with north, and<br />

green with <strong>the</strong> center. See Rebecca L. Twist and Dina Bangdel, “Kalachakra Tantra,” in ibid., pp. 475-479, esp. 478.<br />

Although <strong>the</strong> directional correlations vary depending on <strong>the</strong> text, <strong>the</strong> five basic colors remain <strong>the</strong> same. These<br />

principal colors have been grouped toge<strong>the</strong>r since <strong>the</strong> earliest days <strong>of</strong> Buddhism and are mentioned in <strong>the</strong> Dīrgha<br />

Āgama (Chinese, Chang Ahan jing 長 阿 含 經 ), a collection <strong>of</strong> early Theravada texts translated into Chinese in 413.<br />

For background information on <strong>the</strong> Five Colors (Sanskrit, pañca-varnā), see “ゴシキ| 五 色 ” in Mochizuki Shinkō 望<br />

月 信 亨 , Bukkyō daijiten 佛 教 大 辞 典 , vol. 2 (Tokyo: Bukkyō daijiten hakkōjo, 1931-1963), 1189-1190. At least one<br />

scholar has suggested that because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir vibrancy, ancient Indian religious practitioners were prohibited from<br />

using <strong>the</strong>se five colors for <strong>the</strong>ir robes. See “ 五 色 ” in Nakamura Hajime 中 村 元 , Bukkyōgo daijiten 佛 教 語 大 辞 典 ,<br />

vol. 1 (Tokyo: Tōkyō shoseki, 1975), 363.<br />

11 Directionality is perhaps most clearly embedded in <strong>the</strong> Diamond and Womb World <strong>Mandala</strong>s (Japanese:<br />

Kongōkai mandara 金 剛 界 曼 荼 羅 and Taizōkai mandara 胎 蔵 界 曼 荼 羅 ) employed in Japanese Shingon 真 言 and<br />

Tendai 天 台 Buddhism. The mandalas are hung facing each o<strong>the</strong>r, with <strong>the</strong> Diamond World on <strong>the</strong> western wall<br />

and <strong>the</strong> Womb World on <strong>the</strong> eastern wall. All <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> deities in <strong>the</strong>se mandalas, many <strong>of</strong> whom are associated with<br />

a particular direction, are placed in accordance with <strong>the</strong> directional scheme implied by <strong>the</strong> hanging <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

mandalas. Thus, in <strong>the</strong> Diamond World <strong>Mandala</strong>, Amitābha, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> West, is always depicted at <strong>the</strong> top<br />

(i.e., west) <strong>of</strong> a group <strong>of</strong> deities, while in <strong>the</strong> Womb World <strong>Mandala</strong>, he is always depicted at bottom. For an<br />

introduction to <strong>the</strong>se mandalas, see Elizabeth ten Grotenhuis, Japanese <strong>Mandala</strong>s: Representations <strong>of</strong> Sacred<br />

Geography (Honolulu: University <strong>of</strong> Hawai’i Press, 1999), pp. 33-95.<br />

12 See Snellgrove, The <strong>Hevajra</strong> Tantra, vol. 1, pp. 111-112. A convenient chart may also be found in Zhu, “<strong>Hevajra</strong><br />

Tantra,” in Huntington and Bangdel, p. 456.<br />

13 Zhu, “<strong>Hevajra</strong> Tantra,” in Huntington and Bangdel, p. 455.<br />

The Pulitzer Foundation for <strong>the</strong> Arts<br />

<strong>Reflections</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>

<strong>Four</strong>-<strong>circle</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> <strong>Mandala</strong> 5<br />

These four primary mandalas are surrounded by a variety <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r figures, both monks and deities;<br />

unfortunately, <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> accompanying inscriptions makes identifying many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> figures ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

difficult. The figures are, however, arrayed in a systematized way. At <strong>the</strong> center <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> thangka sits <strong>the</strong><br />

large figure <strong>of</strong> a monk in full lotus position (Sanskrit: padma-āsana) attended by two male deities<br />

(perhaps bodhisattvas), all three <strong>of</strong> whom are framed by a blue niche. The central figure makes <strong>the</strong><br />

dharmacakra-mudrā, <strong>the</strong> gesture <strong>of</strong> teaching, while holding <strong>the</strong> stalks <strong>of</strong> two lotuses, which rise to his<br />

shoulders, with his fingers. Unfortunately, <strong>the</strong> lotus blossoms do not support any attributes that might<br />

allow us to identify <strong>the</strong> figure, leaving us to speculate that <strong>the</strong> figure may represent an eminent monk<br />

revered by <strong>the</strong> donor <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> painting, perhaps <strong>the</strong> recently deceased abbot <strong>of</strong> a temple. In front <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se<br />

three main figures are lotus flowers in a vase, presumably an <strong>of</strong>fering.<br />

Above, to <strong>the</strong> left, and to <strong>the</strong> right <strong>of</strong> this central niche are figures that may be identified as<br />

mahāsiddhas, particularly revered, almost mythical monks, who, in this case, are among <strong>the</strong> earliest<br />

members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lineage from which <strong>the</strong> Sakya order understood <strong>the</strong>mselves to be descended. 14 At top<br />

is Virūpa; at right, Dombi Heruka, a disciple <strong>of</strong> Virūpa who received from him initiation into <strong>the</strong> practices<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> and who is identifiable by his act <strong>of</strong> embracing a consort while riding a tiger. 15 At left we see<br />

a blue male figure who is being approached by a white female figure; although I have not been able to<br />

identify this mahāsiddha conclusively, because he is grouped with Virūpa and Dombi Heruka, it seems<br />

likely that he is Kānha, <strong>the</strong> second disciple <strong>of</strong> Virūpa to receive <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> teachings. I have not been<br />

able to identify <strong>the</strong> monks above, to <strong>the</strong> left, and to <strong>the</strong> right <strong>of</strong> this central figure; each is attended by<br />

two to three wrathful deities, whom I also have yet to identify.<br />

The three deities interspersed at <strong>the</strong> lower boundaries <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two lower mandalas can be identified as a<br />

white manifestation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sixteen-armed Hrdaya-<strong>Hevajra</strong> and his consort Nairātmyā at center; an<br />

independent Nairātmyā, dancing on a corpse and holding a skull cup and dagger, with <strong>the</strong> khatvāṅga, or<br />

staff, resting against her shoulder; and a red Kurukullā, a four-armed female deity again dancing on a<br />

corpse and drawing a bow and arrow and carrying a hook and a red lotus in her remaining two hands.<br />

The presence <strong>of</strong> Nairātmyā 16 and Kurukullā 17 perhaps may be explained by <strong>the</strong>ir being described in <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Hevajra</strong>-tantra. Nairātmyā is, <strong>of</strong> course, omnipresent in <strong>the</strong> text as <strong>Hevajra</strong>’s consort, yet <strong>the</strong> text also<br />

makes her <strong>the</strong> focus <strong>of</strong> an independent mandala; meanwhile, Kurukullā is described as a particularly<br />

powerful being, meditation upon whom “brings <strong>the</strong> threefold world to subjection.” While it is relatively<br />

common to depict duplicate forms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> principal deity <strong>of</strong> a mandala in <strong>the</strong> thangka’s interstitial spaces,<br />

I have not found an explanation <strong>of</strong> why this is done.<br />

14 For an extensive discussion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> depictions <strong>of</strong> lineages in Tibetan thangkas, see David P. Jackson, The Nepalese<br />

Legacy in Tibetan Painting (New York: Rubin Museum <strong>of</strong> Art, 2010), esp. pp. 23-51.<br />

15 In attempting to identify deities, I relied primarily on <strong>the</strong> identification <strong>of</strong> figures in mandalas published in John C.<br />

Huntington and Dina Bangdel, The Circle <strong>of</strong> Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art (Columbus and Chicago: Columbus<br />

Museum <strong>of</strong> Art and Serindia Publications, 2003); Marilyn M. Rhie and Robert A. F. Thurman, Worlds <strong>of</strong><br />

Transformation: Tibetan Art <strong>of</strong> Wisdom and Compassion (New York: Tibet House in association with <strong>the</strong> Shelley<br />

and Donald Rubin Foundation, 1999), esp. pp. 280-311; Marilyn M. Rhie and Robert A. F. Thurman, Wisdom and<br />

Compassion: The Sacred Art <strong>of</strong> Tibet (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1991), pp. 199-235; and <strong>the</strong> online database<br />

“Himalayan Art,” . After determining a possible identity for <strong>the</strong> figure, I <strong>the</strong>n consulted<br />

any relevant entries in Lokesh Chandra, Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Buddhist Iconography (New Delhi: International Academy <strong>of</strong><br />

Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan, 2002), which, unfortunately, does not include entries on most monks or<br />

mahāsiddhas.<br />

16 See, for example, <strong>the</strong> description <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mandala devoted to Nairātmyā in Snellgrove, The <strong>Hevajra</strong> Tantra, pp.<br />

73-78.<br />

17 See, for example, ibid., p. 87.<br />

The Pulitzer Foundation for <strong>the</strong> Arts<br />

<strong>Reflections</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>

<strong>Four</strong>-<strong>circle</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> <strong>Mandala</strong> 6<br />

The composition <strong>of</strong> this thangka is bounded at top and bottom by a register <strong>of</strong> figures depicted in<br />

arcaded niches. Such a compositional device seems to be unique to, and ubiquitous in, Sakya-school<br />

painting from <strong>the</strong> fourteenth through seventeenth centuries. 18 Stylistically similar arches—composed <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> same gilt, vase-like columns, supported by lotus pedestals and supporting semicircular arches,<br />

among which are depicted gilt lozenges surrounded by red and green leaves—may be found in a<br />

fifteenth-century Bhūtadāmara <strong>Mandala</strong> from a central Tibetan Sakyapa 19 monastery, now held in a<br />

private collection. 20 The thangka from <strong>the</strong> private collection, however, appears to have been painted<br />

with even greater care than <strong>the</strong> Harvard thangka: <strong>the</strong> lines are stronger and more even, <strong>the</strong> colors have<br />

been applied more smoothly, and <strong>the</strong> forks <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> foliated flames are finer. Despite <strong>the</strong> differences in<br />

<strong>the</strong> fineness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> execution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> two thangkas, <strong>the</strong>y share many stylistic similarities, perhaps giving<br />

fur<strong>the</strong>r support to <strong>the</strong> recent re-attribution <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Harvard mandala from <strong>the</strong> seventeenth or eighteenth<br />

century to <strong>the</strong> fifteenth or sixteenth century. 21 The lack <strong>of</strong> any cloudforms or landscape elements in <strong>the</strong><br />

Harvard mandala—motifs that appear rarely, if ever, in mandalic thangkas prior to <strong>the</strong> seventeenth<br />

century—seems to preclude <strong>the</strong> possibility that this work dates from a later period. 22 Indeed, <strong>the</strong> work<br />

possesses all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> elements that Pratapaditya Pal enumerates as hallmarks <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sakya painting style<br />

from <strong>the</strong> fourteenth through seventeenth centuries—namely, “(i) <strong>the</strong> ubiquitous use <strong>of</strong> red…; (ii) strictly<br />

linear definition <strong>of</strong> form; (iii) employment <strong>of</strong> elaborate shrines with ornate columns from which spring<br />

foliate arches … carrying mythical creatures such as makara, garuda, [and] nāga …; (iv) registers <strong>of</strong><br />

figures both at <strong>the</strong> top and <strong>the</strong> bottom, generally clearly separated by miniature shrines <strong>of</strong> arches and<br />

columns; (v) and a pr<strong>of</strong>usion <strong>of</strong> subtle, densely packed stylized scrollwork in <strong>the</strong> background.” 23<br />

The figures in <strong>the</strong> upper arcade <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> painting constitute a schematic portrait <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lineage <strong>of</strong> Sakyapa<br />

patriarchs. It begins at far left with <strong>the</strong> Ādi-<strong>Buddha</strong> Vajradhara, <strong>the</strong> primordial being whom <strong>the</strong> Sakyapa<br />

consider <strong>the</strong> progenitor <strong>of</strong> all things, identifiable by his blue body, as well as <strong>the</strong> vajra and bell that he<br />

holds in his crossed hands. Vajradhara is followed by Nairātmyā, <strong>the</strong> second in <strong>the</strong> Margapala lineage <strong>of</strong><br />

18 For an overview <strong>of</strong> Sakyapa painting, see Pratapaditya Pal, Tibetan Paintings: A Study <strong>of</strong> Tibetan Thankas,<br />

Eleventh to Nineteenth Centuries (Basel: Ravi Kumar/So<strong>the</strong>by Publications, 1984), pp. 61-96.<br />

19 The common Tibetan suffix -pa nominalizes <strong>the</strong> word that it modifies; hence, “Sakyapa” can be understood to<br />

signify “one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sakyas.” Consequently, “Sakya” and “Sakyapa,” or “Gelug” and “Gelugpa, ” are usually used<br />

interchangeably in English.<br />

20 See ibid., plate 33.<br />

21 Information conveyed by Robert D. Mowry, Alan J. Dworsky Curator <strong>of</strong> Chinese Art, Harvard Art Museums, in<br />

personal conversation, May 2011.<br />

22 See Pal, Tibetan Paintings, 121-148. Seventeenth-century <strong>Hevajra</strong> mandalas that include such landscape<br />

elements are included in ibid., pl. 81-82. A nineteenth-century <strong>Four</strong>-Circle <strong>Hevajra</strong> <strong>Mandala</strong> with even more<br />

extensive landscape features is pictured in Pratapaditya Pal, Divine Images, Human Visions: The Max Tanenbaum<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> South Asian and Himalayan Art in <strong>the</strong> National Gallery <strong>of</strong> Canada (Ottawa: National Gallery <strong>of</strong> Canada,<br />

1997), p. 115.<br />

23 Pal, Tibetan Paintings, 62-63. A fifteenth-century <strong>Four</strong>-Circle <strong>Hevajra</strong> <strong>Mandala</strong> is also included in Giuseppe Tucci,<br />

Tibetan Painted Scrolls (Rome: Libreria dello Stato, 1949), plate 214; however, <strong>the</strong> quality <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> image prevents<br />

close examination <strong>of</strong> stylistic details. Jackson, The Nepalese Legacy, esp. pp. 81-97, describes <strong>the</strong> stylistic features<br />

<strong>of</strong> Sakyapa painting with even greater precision. However, Jackson argues that analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> depictions <strong>of</strong><br />

lineages in many thangkas that were assumed to be Sakya works reveals that <strong>the</strong>y were sponsored by o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

schools <strong>of</strong> Tibetan Buddhism. He suggests that from <strong>the</strong> mid-fourteenth to mid-fifteenth centuries, Tibetan<br />

Buddhist shared a universal idiom <strong>of</strong> painting, known as <strong>the</strong> Beri style, which derived from Nepalese sources.<br />

Consequently, he urges that greater caution be used when specifically identifying works in <strong>the</strong> Beri style as “Sakya”<br />

thangkas. Given <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> deities closely associated with Sakya school that are included in <strong>the</strong> Harvard<br />

<strong>Hevajra</strong> mandala, I am confident that we can identify it as a Sakya work.<br />

The Pulitzer Foundation for <strong>the</strong> Arts<br />

<strong>Reflections</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>

<strong>Four</strong>-<strong>circle</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> <strong>Mandala</strong> 7<br />

teachings passed down from Vajrdhara to <strong>the</strong> members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sakya order. Nairātmyā is succeeded by<br />

twelve monks, presumably <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sakya order, paired as though engaged in debate. While <strong>the</strong> colors <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>ir robes and skin, as well as <strong>the</strong>ir facial features differ, <strong>the</strong>y almost all make <strong>the</strong> dharmacakra-mudrā,<br />

a gesture <strong>of</strong> teaching, fitting for patriarchs.<br />

More eclectic is <strong>the</strong> array <strong>of</strong> figures depicted in <strong>the</strong> lower arcade. At lower rights sits ano<strong>the</strong>r monk,<br />

wearing <strong>the</strong> same red robe adorned with golden flower petals as many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r monks in <strong>the</strong><br />

painting. He holds two lotuses in his hands, which form <strong>the</strong> dharmacakra-mudrā. One lotus bears a<br />

vajra, and <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r, a chopper (?)—both ritual implements commonly used in Vajrayāna rites. In <strong>the</strong><br />

niche to <strong>the</strong> monk’s right are arrayed a variety <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r ritual implements, included drums, cymbals,<br />

bowls, and a conch shell (?). Such a display <strong>of</strong> ritual implements or <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>ferings can <strong>of</strong>ten be found in <strong>the</strong><br />

niche next to that which depicts <strong>the</strong> donor <strong>of</strong> a thangka, as is likely true here. The next four deities<br />

depicted are all deities <strong>of</strong> protection and wealth commonly venerated by <strong>the</strong> Sakyapa. First is <strong>the</strong><br />

Śrīdevī Dhūmāvatī, a female deity <strong>of</strong> protection, who, in her Sakyapa form, bears a sword, skull cup,<br />

spear, and trident while riding a donkey. She is <strong>the</strong> consort <strong>of</strong> Mahakala, one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most widely<br />

venerated deities in Tibet. In <strong>the</strong> form commonly worshipped by <strong>the</strong> Sakyapa, he holds a curved knife<br />

with a vajra-like hilt and a skullcup; this form, known as <strong>the</strong> Panjaranata Mahakala, is specified as <strong>the</strong><br />

protector <strong>of</strong> practitioners <strong>of</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> rites in <strong>the</strong> eighteenth chapter <strong>of</strong> Vajrapanjara-tantra, a text<br />

translated into Tibetan in <strong>the</strong> eleventh century that explains practices related to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong>-tantra. 24<br />

The close association <strong>of</strong> this deity with <strong>Hevajra</strong> guaranteed his high place in Sakya practice. Next can be<br />

seen a Yellow Jambhala, a god <strong>of</strong> wealth identifiable by <strong>the</strong> jewel-spewing mongoose that he holds; and<br />

a white figure <strong>of</strong> Prajñāpāramitā, <strong>the</strong> female deity <strong>of</strong> wisdom. 25 Finally, <strong>the</strong> remaining eight dancing<br />

dakinīs, each <strong>of</strong> whom tramples and a corpse and, with <strong>the</strong> exception <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rightmost, bears a skullcup<br />

in her right hand, are <strong>the</strong> same dakinīs that appear in <strong>the</strong> four <strong>Hevajra</strong> mandalas above.<br />

The mandalic composition extends to <strong>the</strong> reverse <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> thangka, as well. There, a three-syllable mantra<br />

consisting <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sanskrit syllables “Om ah hum” transliterated in Tibetan letters has been repeatedly<br />

inscribed, each mantra aligning with <strong>the</strong> position <strong>of</strong> each figure on <strong>the</strong> thangka’s verso. More precisely,<br />

each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se syllables can be understood to align with <strong>the</strong> head, mouth, and heart <strong>of</strong> each figure.<br />

These inscriptions might be seen as empowering <strong>the</strong> figures with supramundane strength, a practice<br />

reminiscent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> installment <strong>of</strong> slips <strong>of</strong> paper inscribed with mantras inside <strong>of</strong> sculptures such as <strong>the</strong><br />

Japanese Kamakura-period (1185-1333) Shotoku taishi nisaizō and <strong>the</strong> Chinese Yongle-era (1402-1424)<br />

Green Tārā also on display in “<strong>Reflections</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>.” 26<br />

24 Linro<strong>the</strong> and Watt, pp. 266-269.<br />

25 The page on Panjarnata Mahakala included in “Himalayan Art” asserts that White Prajñāpāramitā is very<br />

important to <strong>the</strong> “<strong>Hevajra</strong> system <strong>of</strong> practice” and suggests that <strong>the</strong> textual source for this is <strong>the</strong> Vajrapanjaratantra.<br />

(See Jeff Watt, “Mahakala [Buddhist Protector] – Panjarnata [Lord <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Pavilion],” April 2001 [updated<br />

December 2009], .) Unfortunately, I have been unable to<br />

consult a copy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Vajrapanjara-tantra and have yet to find o<strong>the</strong>r sources to verify his claim. Watt’s entry on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Yellow Jambhala similarly asserts <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> this deity in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong>-tantra, though I have been unable<br />

to find any references to Jambhala in <strong>the</strong> translation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tantra that I have. (Jeff Watt, “Buddhist Deity:<br />

Jambhala, Yellow [Main Page],” August 2011 .)<br />

Presumably he only appears in commentaries to <strong>the</strong> tantra. Never<strong>the</strong>less, I have observed that <strong>the</strong>se deities<br />

frequently appear in <strong>Hevajra</strong> <strong>Mandala</strong>s and in Sakya-school paintings more generally.<br />

26 I thank Luo Wenhua 羅 文 華 , a researcher in Tibetan art at <strong>the</strong> Palace Museum, Beijing, for his help in translating<br />

and interpreting <strong>the</strong>se inscriptions.<br />

The Pulitzer Foundation for <strong>the</strong> Arts<br />

<strong>Reflections</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>

<strong>Four</strong>-<strong>circle</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> <strong>Mandala</strong> 8<br />

Despite <strong>the</strong> iconographic precision <strong>of</strong> this work, it can, like many thangkas, be seen as a highly personal<br />

production. Fur<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong> smallness <strong>of</strong> this densely packed painting may be said to belie <strong>the</strong> great variety<br />

<strong>of</strong> functions that it can be understood to have served. On <strong>the</strong> one hand, <strong>the</strong> mandala conforms closely<br />

to <strong>the</strong> textual descriptions <strong>of</strong> such mandalas in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong>-tantra 27 ; fur<strong>the</strong>r, it is a very close tangible<br />

analogue to <strong>the</strong> mental mandalas evoked in <strong>the</strong> text, 28 and it seems possible that it may have been able<br />

to be used in rituals prescribed in <strong>the</strong> commentarial literature that accrued around <strong>the</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong>-tantra.<br />

On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, <strong>the</strong> inclusion <strong>of</strong> a great variety <strong>of</strong> protective deities associated with <strong>the</strong> Sakyapa—<br />

and especially <strong>the</strong> inclusion <strong>of</strong> so many monastic figures, who, it is likely, do not appear in any <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

commentarial literature—define this thangka as a work meant for <strong>the</strong> visualization practices <strong>of</strong> a<br />

particular patron. This patron both paid homage to his teachers by depicting <strong>the</strong>m in <strong>the</strong> mandala and<br />

perhaps used <strong>the</strong>se same depictions as means <strong>of</strong> making a claim to a particular lineage <strong>of</strong> teaching. In a<br />

sense, it is a work that was fashioned by <strong>the</strong> patron while it simultaneously fashioned that same patron.<br />

While we may not be able to recover <strong>the</strong> fully <strong>the</strong> original context from this thangka came, <strong>the</strong><br />

personalized pan<strong>the</strong>on diagrammed in this image provide clues sufficient to allow us to imagine<br />

something <strong>of</strong> its origin.<br />

Phillip E. Bloom<br />

Ph.D. Candidate, Department <strong>of</strong> History <strong>of</strong> Art and Architecture<br />

Harvard University<br />

Pulitzer Foundation Graduate Student Research Assistant<br />

Harvard Art Museums<br />

27 For example, Snellgrove, The <strong>Hevajra</strong> Tantra, vol. 1, p. 51, mentions <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> a mandala focused on a sixteenarmed,<br />

snake-trampling <strong>Hevajra</strong> in a rain-producing ritual.<br />

28 The mental mandalas are described in ibid., pp. 56-69.<br />

The Pulitzer Foundation for <strong>the</strong> Arts<br />

<strong>Reflections</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>

<strong>Four</strong>-<strong>circle</strong> <strong>Hevajra</strong> <strong>Mandala</strong> 9<br />

Publication History<br />

Unpublished<br />

Works Consulted<br />

Lokesh Chandra. Dictionary <strong>of</strong> Buddhist Iconography. New Delhi: International Academy <strong>of</strong> Indian<br />

Culture and Aditya Prakashan, 2002.<br />

Elizabeth ten Grotenhuis. Japanese <strong>Mandala</strong>s: Representations <strong>of</strong> Sacred Geography. Honolulu:<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Hawai’i Press, 1999.<br />

“Himalayan Art Resources.” Maintained by <strong>the</strong> Shelley and Donald Rubin Foundation.<br />

.<br />

John C. Huntington and Dina Bangdel. The Circle <strong>of</strong> Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art. Exh. cat. Columbus<br />

and Chicago: Columbus Museum <strong>of</strong> Art and Serindia Publications, 2003.<br />

David P. Jackson. The Nepalese Legacy in Tibetan Painting. New York: Rubin Museum <strong>of</strong> Art, 2010.<br />

Deborah E. Klimburg-Salter et al. The Silk Route and <strong>the</strong> Diamond Path. Exh. cat. Los Angeles: Frederick<br />

S. Wight Art Gallery, University <strong>of</strong> California at Los Angeles, 1982.<br />

Rob Linro<strong>the</strong> and Jeff Watt. Demonic Divine: Himalayan Art and Beyond. Exh. cat. New York: Rubin<br />

Museum <strong>of</strong> Art, 2004.<br />

Mochizuki Shinkō 望 月 信 亨 . Bukkyō daijiten 佛 教 大 辞 典 . 6 vols. Tokyo: Bukkyō daijiten hakkōjo,<br />

1931-1963.<br />

Nakamura Hajime 中 村 元 . Bukkyōgo daijiten 佛 教 語 大 辞 典 . 2 vols. Tokyo: Tōkyō shoseki, 1975.<br />

Pratapaditya Pal. Divine Images, Human Visions: The Max Tanenbaum Collection <strong>of</strong> South Asian and<br />

Himalayan Art in <strong>the</strong> National Gallery <strong>of</strong> Canada. Exh. cat. Ottawa: National Gallery <strong>of</strong> Canada,<br />

1997.<br />

--. Tibetan Paintings: A Study <strong>of</strong> Tibetan Thankas, Eleventh to Nineteenth Centuries. Basel: Ravi<br />

Kumar/So<strong>the</strong>by Publications, 1984.<br />

Marilyn M. Rhie and Robert A. F. Thurman. Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art <strong>of</strong> Tibet. Exh. cat.<br />

San Francisco and New York: Asian Art Museum in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1991.<br />

--. Worlds <strong>of</strong> Transformation: Tibetan Art <strong>of</strong> Wisdom and Compassion. Exh. cat. New York: Tibet House<br />

in association with <strong>the</strong> Shelley and Donald Rubin Foundation, 1999.<br />

David L. Snellgrove. Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and Their Tibetan Successors. Boston:<br />

Shambhala, 2002.<br />

David L. Snellgrove. The <strong>Hevajra</strong> Tantra: A Critical Study. London: Oxford University Press, 1959.<br />

Giuseppe Tucci. Tibetan Painted Scrolls. Rome: Libreria dello Stato, 1949.<br />

The Pulitzer Foundation for <strong>the</strong> Arts<br />

<strong>Reflections</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Buddha</strong>