PDF version - The Wholenote Magazine

PDF version - The Wholenote Magazine

PDF version - The Wholenote Magazine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

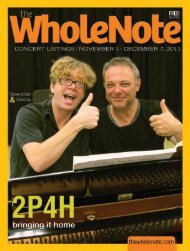

CONVERSATIONS at THE WHOLENOTEComposerLeap Frog withAustin Clarkson✒ David PerlmanAt some point in my recent conversationwith musicologist Austin Clarksonhe used the phrase “leapfrogging seriesof interactions” to describe the relationshipsamong four composers,Anton Webern,Stefan Wolpe, MortonFeldman andJohn Cage.“Stefan meetsAnton and Mortymeets John” is thetitle of an October 6concert and accompanyingseminar,both curated byClarkson, to launchthe 43rd season ofNew Music Concertswith whom Clarksonhas had a relationshipspanningmore than two and ahalf decades. Whilethe four composersin question never allmet, the intersections of their lives and workmake for an interesting daisy chain of musicalthought and circumstance.Clarkson explains: “Cage had met MortonFeldman at a concert in Carnegie Hall conductedby Dmitri Mitropoulos with the NewYork Philharmonic playing the Webern SymphonyOp.21. <strong>The</strong>y both left the concert at thesame time and Morty went up to John and said,‘Wasn’t that beautiful.’ Because he [Feldman]had already seen John Cage at a meeting atone of the musicales at the Wolpe apartmentuptown, and had not spoken to him. But thistime he spoke to him.”<strong>The</strong> date of this concert was January 26, 1950,and it was, by several accounts, a memorableoccasion. Music writer Alex Ross, for one, inhis book <strong>The</strong> Rest Is Noise asserts that the twoleft the concert early, equally disgusted at thereaction of the New York Phil audience to theWebern piece.“Sounds as if it was in that mandatory ‘beforethe intermission’ slot for new music” I posit toClarkson, and he briefly nods assent to thenotion before carrying on with his story:“So Feldman at that time was writing a stringquartet also, which he came to call Structures,Clarkson with <strong>The</strong> WholeNote editor Perlman.“I had written my thesis onStravinsky’s Symphony inThree Movements —but Wolpe was beyond that”and he by that time had left the Wolpe studio— he wasn’t taking lessons anymore — andhe was kind of trying to find his own way,very much involved with the New York painters.And so Cageinvited him to hisapartment down onthe East River, andMorty showed himthis draft of thisstring quartet. AndCage said, ‘Well howdid you make that?’He was fascinated.And Morty said, ‘Idon’t know.’”Leapfrog, indeed,among the composers;even more interesting,as it emergesduring the conversation,is the way inwhich Clarkson’sown musical life hasbeen inextricablyinterwoven with thelives of his musical subjects, above all Wolpe.“When did you discover [Wolpe’s]work?” I ask.“Well, I discovered his work in Sam’s recordshop when it was on College St., west ofBathurst. And it was 1957 or ’6 when I wasworking in Saskatchewan at the University ofSaskatchewan in Saskatoon (my first job aftergraduating from Eastman). And I was thumbingthrough the new releases and I picked upthis LP and saw the face of this composer inmany different angles and moods, from laughingto looking very pensive, and he had an openshirt, and he was so out there. And I thoughtthis must be interesting, so I turned it over,and there Aaron Copland had a blurb sayingthat Wolpe was one of the most importantcomposers of this era. So I thought well I’lltry this and I took it home and played it. And Ithought it was absolutely ... bizarre. I could notunderstand it. I had gotten as far as Bartók andStravinsky — I had written my thesis on Stravinsky’sSymphony in Three Movements — butWolpe was beyond that. And when I played itfor my friends they thought this is absolutelyridiculous. So then I get to New York and I’mstudying for my doctorate at Columbia, andmy roommate who was a pianist studying andteaching at Juilliard said would I like to join asmall group of students who are studying withthis composer who needs money because heis very poor, and my girlfriend is a student ofhis wife’s. And I said what’s his name? And hesaid, Stefan Wolpe.”“When I first went into his room, his thirdfloor walk-up, on West 70th St., it was likewalking into a seismic event,” Clarkson says.“This man radiated the kind of energy that youdidn’t believe people could provide — just likean everyday thing. Also he revealed that musicwas beyond something I had ever experiencedup until that point. And I realized that it wasgoing to be really a life’s work to becomeadequate to this way of being in music. Sothat’s where it began.”Wolpe died in 1972 ofParkinson’s, and, asClarkson explains it,“So I finished myPh.D. ... and I wasthe only musicologistreally inhis circle. <strong>The</strong>rewas one other butshe was a really terrificpianist and she wasdevoted to that career, although she did a greatdeal. So it turned out that I had to become aWolpe specialist. <strong>The</strong>re didn’t seem to be anyoneelse to do it.”Wolpe’s pivotal role in this game of composerleapfrog becomes more clear asClarkson describes the program for theOctober 6 concert.“<strong>The</strong> first piece I chose was a Concerto forNine Instruments that Wolpe wrote while hewas studying with Webern ... in Vienna,” Clarksonexplains. “He’d arrived in Vienna as a refugeefrom Nazi Berlin, just in September of 1933,and he had three months with Webern beforethe Austrian police expelled him from Austriawith the threat to deport him back to Germany.And so in those three months he composed thisconcerto for nine instruments. And at the sametime, curiously, Webern was composing hisown concerto which turned out to be for nineinstruments eventually. So there are those twokey pieces, the Wolpe concerto and the Webernconcerto, both for nine instruments, almostexactly the same instruments.”“And then the next piece chronologically isJohn Cage’s String Quartet, and it’s a piece hewrote beginning in Paris when he was thereon a fellowship to study at the BibliothèqueNationale the music of Satie, but while he wasthere he met Boulez and he went to the studioof Messiaen and played his Sonatas and Interludesand began his string quartet. And he finishedit the next year in 1950.”It’s from “a whole period of classical Cage,”Clarkson says, “that people don’t know muchabout. Because after he turned to indeterminacyhe became the Cage we all knowtoday ... <strong>The</strong> string quartet is a masterpiece. It’sa classic. And yet we don’t hear it very muchbecause it’s the other Cage that we know moreabout, that we hear more about.”12 | September 1 – October 7, 2013 thewholenote.comCage.