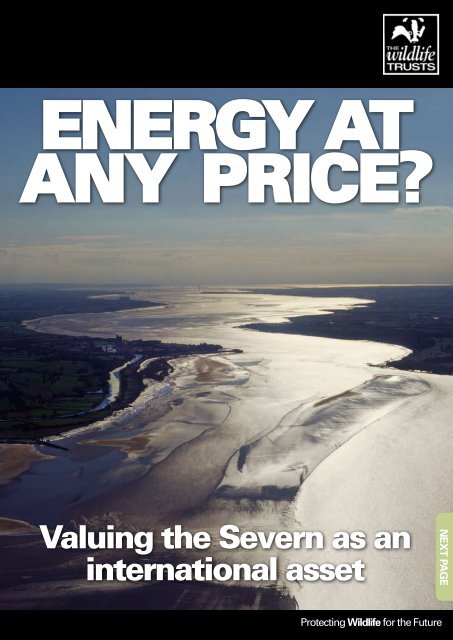

Energy at any price? - Gwent Wildlife Trust

Energy at any price? - Gwent Wildlife Trust

Energy at any price? - Gwent Wildlife Trust

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

26平 成 27 年4 月 19 日日 立 市 東 成 沢 町 3 丁 目 7 番 7 号会 社 員無 所 属しゅんいちあおき 俊 一男昭 和 29 年8 月 24 日(60 歳 )本 人 届 出27平 成 27 年4 月 19 日日 立 市 諏 訪 町 5 丁 目 1 番 9 号白 山 代 表無 所 属せんざぶろうしらと 仙 三 郎男昭 和 21 年2 月 22 日(69 歳 )本 人 届 出28平 成 27 年4 月 19 日日 立 市 弁 天 町 3 丁 目 4 番 19 号日 立 市 議 会 議 員日 本 共 産 党こばやしこ小 林 まみ 子http://www.jcp-net.jp/ibahoku/女昭 和 39 年3 月 26 日(51 歳 )本 人 届 出29平 成 27 年4 月 19 日日 立 市 高 鈴 町 2 丁 目 5 番 10 号政 党 役 員公 明 党しもやまだ下 山 田 みきこhttp://www.komei.or.jp/km/simomiki/女昭 和 34 年6 月 19 日(55 歳 )本 人 届 出30平 成 27 年4 月 19 日日 立 市 久 慈 町 3 丁 目 6 番 9 号久 慈 町 漁 業 協 同 組合 顧 問無 所 属けんいちとびた 謙 一男昭 和 24 年12 月 25 日(65 歳 )本 人 届 出31平 成 27 年4 月 19 日日 立 市 水 木 町 2 丁 目 32 番 7 号日 立 金 属 株 式 会 社社 員無 所 属ひろみおおば 弘 美男昭 和 31 年8 月 24 日(58 歳 )本 人 届 出32平 成 27 年4 月 19 日日 立 市 石 名 坂 町 2 丁 目 17 番 2 号 無 職無 所 属かずやまつざき 和 也男昭 和 63 年8 月 9 日(26 歳 )本 人 届 出4 / 4

AT RISKAbout 80 times a yearthe incoming tide andthe Estuary’s funnelshape cre<strong>at</strong>e theSevern Bore – and thechance to surf formiles in fresh w<strong>at</strong>erThe BoreThe Estuary is exceptional for fishing and birdw<strong>at</strong>ching. And theSevern Bore is one of the UK’s gre<strong>at</strong>est n<strong>at</strong>ural phenomenaAndrew MawbyDavid ChapmanMike LaneDavid WoodfallPREVIOUS PAGEAs dawn breaks overGloucestershire a strange sceneunfolds in a pub car park. Thisis Arlingham on the banks ofthe Severn, but it is a sight morecommonly associ<strong>at</strong>ed with the beaches ofDevon and Cornwall. Men and women aredonning wetsuits, waxing their surfboards andentering the w<strong>at</strong>ers of the river.The opposite bank is already thronged withpeople holding video cameras and binoculars.Everyone is gazing downstream, straining tobe the first to glimpse the oncoming tide. Butit’s their ears th<strong>at</strong> sense it first. Initially a dullrumble, the sound intensifies until by the timethe Severn Bore is visible, rounding the finalbend, it sounds like an approaching train.The surfers clamber onto their boards. Forsome, it will be the longest ride of their lives; afew have managed over six miles. Thespect<strong>at</strong>ors are about to witness one of the UK’smost spectacular n<strong>at</strong>ural phenomena.The Bore is born in the funnel-shaped,strongly tidal Estuary. The massive incomingtide is squeezed into a smaller and smallerspace until the w<strong>at</strong>er has no choice but to pileup, forming a wave th<strong>at</strong> travels upstream formore than 30 miles, <strong>at</strong> speeds of up to 15mph.Over the ages the Bore has become part ofthe river’s ecosystem. But it’s also important topeople. M<strong>any</strong> businesses benefit from thetourism the Bore cre<strong>at</strong>es, whilst salmon andelver fishermen rely on it for their livelihood.The Bore is also incredibly important to thesurfers th<strong>at</strong> ride it. As well as the hundreds ofcoastal surfers who come for the largest tidesthere is a tight-knit group who organise theirlives around the lunar cycle, so th<strong>at</strong> they canbe in the river the next time the Bore roundsth<strong>at</strong> bend. But a device th<strong>at</strong> reduces the river’stidal range would elimin<strong>at</strong>e all th<strong>at</strong>.Dave Butterton, Bore surferThe Estuary provides m<strong>any</strong> forms of recre<strong>at</strong>ion. Itslandscape brings walkers and sightseers from allover Wales, the South West and the MidlandsIt’s quite possible to spend a lifetime birdw<strong>at</strong>chingin the Estuary (see page 14). Hundreds of species,some from half way round the world, pass throughMore than 100 species of fish are found in the riverSevern and its Estuary. Some of the most soughtafterspecies migr<strong>at</strong>e into its eight tributary riversNEXT PAGE8 The <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s’ Severn Estuary reportThe <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s’ Severn Estuary report 9

AT RISKLike m<strong>any</strong> visitingwaders, knot g<strong>at</strong>herin the Estuary inhuge flocksRefuge for birdsPREVIOUS PAGEThey arrive by the thousand, from Canada, Africa and Russia.And they come to the Estuary for food, rest and shelterIhave w<strong>at</strong>ched birds on theGloucestershire sector of the SevernEstuary since I was ten, when I made the50-mile round trip by bicycle everyweekend. Some early highlights arousefond memories: th<strong>at</strong> snow bunting in October1953, or the red-thro<strong>at</strong>ed diver <strong>at</strong> high tide inJanuary 1956. But it’s the regular visitorswhich leave the lasting impression.For example, Slimbridge is a winter refugefor white-fronted geese and thousands ofwigeon, teal and pintail, which migr<strong>at</strong>e everyyear from Russian breeding grounds to theterminus <strong>at</strong> the westernmost end of their3,000 mile flyway. In the cold winter of 1962they were joined by a massive arrival ofRussian Bewick’s swans, which havecontinued to come ever since, though like thewhitefronts their numbers have decreased.The Severn is also an essential refuellingstop for long distance migrants th<strong>at</strong> winter insub-Saharan Africa and pass through the UKtwice: in spring, on their way to Arcticbreeding grounds in Canada and the Russiantundra; then again in early autumn on theirway back. Waders like bar-tailed godwit orlittle stint use the short tundra summer toh<strong>at</strong>ch their young; within a few days the adultsleave, arriving on the Severn in l<strong>at</strong>e July orAugust before moving on to places such as theBanc d’Aguin in Mauritania, or even SouthAfrica. Their young find their own way amonth or so l<strong>at</strong>er.Quite apart from the navig<strong>at</strong>ional fe<strong>at</strong>, thephysiological performance is exceptional; bothyoung and adults put on half their bodyweight in f<strong>at</strong> to enable them to make theseThe adults leave their young inthe Arctic, arriving on the Severnin July before moving on to Africaflights. They use up this extra f<strong>at</strong> in migr<strong>at</strong>ion,so stops in biologically rich estuaries are vital.Then, having wintered in warmer climes, theyare back on the Estuary the following spring,together with other waders like whimbrelwhich g<strong>at</strong>her in the western UK to refuel, enroute to their Icelandic nesting grounds.In cold snaps the Estuary’s brackish w<strong>at</strong>erremains ice free, <strong>at</strong>tracting birds from inlandsites like the Somerset Levels or the SevernVale. Waders such as lapwing or goldenplover, together with ducks from riversidemarshes, flock to the Estuary <strong>at</strong> these times.In every way, then, the Severn Estuary is abird site for all seasons.Mike Smart, <strong>Trust</strong>eeGloucestershire <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>Besides the huge flocks,the rarities. This is apomarine skua, pausinghalf way between the farNorth and the tropicsDavid Sl<strong>at</strong>erNEXT PAGE14 The <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s’ Severn Estuary reportThe <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s’ Severn Estuary report 15

How the Estuaryecosystem worksIt all begins with washed-in organic debris.Then the mud dwellers get to workThe Severn Estuary is a hugely productiveplace, but th<strong>at</strong> productivity isn’t driven directlyby green plants and the sun. Instead theEstuary acts like a gigantic reprocessing plant,using as its raw m<strong>at</strong>erial plankton and flotsamwashed in from the sea and tributary rivers,plus churned-up sand-dwelling microscopicplants. In the mud and silt of the intertidalzone (between high and low tide), billions ofinvertebr<strong>at</strong>es and bacteria convert this debrisinto protein.With fast, silt-laden currents in the centralchannel, most of the pred<strong>at</strong>ion happens in theintertidal zone. The fish grab the worms andshellfish <strong>at</strong> high tide, with the prawns andcrustaceans hoovering up the bits; six hoursl<strong>at</strong>er it’s the birds’ turn.Most of the Estuary’s ecology happens inthe intertidal zone. Reduce its extent, and youlose most of th<strong>at</strong> huge productivity, withknock-on effects to ecosystems elsewhere.Overleaf shows where they are.The humble lugworm.Estuary mud and sandcontains rel<strong>at</strong>ively fewspecies, but in huge numbersVital st<strong>at</strong>istics of the Estuary ecosystem10,000,00069,00024,70020,9585,0001,5001,400100+10estim<strong>at</strong>ed tonnes of sediment carried upand down the Estuary on a spring tidevisiting birds, either sheltering from the Arctic winter or refuelling duringtheir spring/autumn migr<strong>at</strong>ion between north and south hemisphereshectares of the Severn Estuary in total,making it one of the largest in Europehectares of mud and sand fl<strong>at</strong>s –the fourth largest expanse in the UKyears of sediment<strong>at</strong>ion evidence in the Estuary – avaluable geomorphological and archaeological historyhectares of rock, boulder, mussel/cobble scars,rocky pools and shinglehectares of salt marsh –the largest expanse in the South Westspecies of fish foundin the Estuaryspecies of commercial fish use the Estuary in their life cycle: herring, cod,plaice, sole, whiting, blue whiting, hake, horse mackerel, ling and saitheDavid ChapmanZONESCHARACTERISTICSLarge tidal rangeHABITATSSaltmarshWILDLIFEFishPREVIOUS PAGEEXPOSED INTERTidalSUBMERGEDThe key feeding zone: birds<strong>at</strong> low tide, fish <strong>at</strong> high tideThe silty w<strong>at</strong>er looks lifeless but,as this salmon trap shows, is acorridor and food supplyDavid Woodfall David WoodfallLarge intertidal areaLots of suspendedm<strong>at</strong>erialNutrient richStrong currentsHighly productivehabit<strong>at</strong>sSandbanksMudfl<strong>at</strong>s rich in wildlifeRock and shingleshoreline habit<strong>at</strong>sLow and high salinityw<strong>at</strong>erShallow sandbanksSilt laden currentsMuddy seabed rich inwildlifeShallow w<strong>at</strong>er-churnedseabedNeil HepworthPlant planktonRick ParkSand-dwellingwormsDavid ChapmanShellfishAlgal andplant communitiesDavid Sl<strong>at</strong>erMid-w<strong>at</strong>erfishPaul NaylorAnimal planktonRick ParkBirdsDavidSl<strong>at</strong>erSand-dwellingdi<strong>at</strong>omsSea mammalsFlorian GranerN<strong>at</strong>ure PLAnson MacKayPaul NaylorBottom-dwellingfishHans HillewaertSand-dwellinginvertebr<strong>at</strong>esPaul HobsonCrustaceansPaul NaylorOtherinvertebr<strong>at</strong>esDavid ChapmanTURN THEPAGE FOR THEMAIN EFFECTSON OTHERECOSYSTEMSNEXT PAGE16 The <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s’ Severn Estuary reportThe <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s’ Severn Estuary report 17

iStock PhotoThe global impactBirds and fish disperse the Estuary’s energy andproductivity to ecosystems across the globeEelsAfter m<strong>at</strong>uring in fresh w<strong>at</strong>er, adultsswim across the Atlantic to spawn anddie in the Sargasso Sea. The larvae arethought to return on North Atlanticcurrents. Numbers of eels havedeclined hugely in recent years, forreasons which are not fully understood.The previous pages explain how the Estuarygener<strong>at</strong>es very large amounts of biomass (thesheer weight of living things), most of it fromthe intertidal zone.Because most of the Estuary’s pred<strong>at</strong>ors arehighly mobile fish and birds, they effectivelytransport the energy and m<strong>at</strong>erial they pick upin the mud to other places. This energy andm<strong>at</strong>erial is carried in these animals’ bodytissues and guts, and transmitted via theirparticip<strong>at</strong>ion in other ecosystems where theyfeed, are fed on, and eventually die anddecompose. Millions of fish and birds movingaround is impressive enough, but they keep upthese movements year after year, and thecumul<strong>at</strong>ive effect is astronomical. Without theSevern’s effect as a stopover and refuel facility,for example, the Arctic tundra couldn’tsupport so m<strong>any</strong> migr<strong>at</strong>ory waders. Withoutits effect as a huge fish nursery, the Celtic Sea(and the Atlantic Ocean beyond) could notsupport so m<strong>any</strong> salmon, spr<strong>at</strong>s or mackerel.This extreme interconnectedness is wh<strong>at</strong>makes altering the Severn’s intertidal habit<strong>at</strong> sorisky. Does the Estuary’s energy prize justifysevering these global wildlife links, with theirbenefits to people which are not yet fullyunderstood?Dispersal happens across the UK tooLittle is known of the eel’s migr<strong>at</strong>ion routesSalmonPrincipal feeding grounds are north ofthe Faeroes; adults are <strong>at</strong> sea for up tofour years. Most popul<strong>at</strong>ions are indecline. The sea trout, another migrant,is thought to stay near the UK coast, asdo the allis and twaite shad (the Severnshad are genetically distinct species).Mike LanePREVIOUS PAGEThe <strong>Gwent</strong> LevelsHabit<strong>at</strong> for a huge diversityof birds. M<strong>any</strong> are relianton the Estuary’s mudfl<strong>at</strong>sfor their source of foodThe Severn’s tributariesThe rivers are fine habit<strong>at</strong>sfor resident and migr<strong>at</strong>oryfish which feed in (andpass through) the EstuaryThe Somerset LevelsThe Levels and the RiverParrett are excellenthabit<strong>at</strong>s for resident andmigr<strong>at</strong>ory birds, m<strong>any</strong> ofwhich feed in the EstuaryThe local effectAnimal movements disperse largequantities of energy and m<strong>at</strong>erialfrom the Severn Estuary toneighbouring systems in theregion. The key areas to benefitare the rivers Parrett in Somerset,Usk in Wales, the Wye either sideof the border, and the <strong>Gwent</strong> andSomerset LevelsReasons for salmon declines are complexBirdsWith several dozen species andsub-popul<strong>at</strong>ions involved, the routesshown here are hugely simplified. Butessentially there are three sorts of birdmigr<strong>at</strong>ion through the Estuary.The spring passage from Africa,branching west to breeding grounds inIceland and Greenland, or east tonorthern Europe and Russia.The return journey, from l<strong>at</strong>e June toOctober, by adults and young.The winter visitors, which don’t gofurther south than the Estuary, andreturn north in spring to breed.Bar-tailed godwits: 300 grams of pure energyLaurie CampbellColin VarndellNEXT PAGE18 The <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s’ Severn Estuary reportThe <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s’ Severn Estuary report 19

The optionsThere are five on the shortlist, with three SETS options needing furtherresearch. Here are their environmental, energetic and cost analysesThese are the choices facing the UKGovernment as it tackles ourclim<strong>at</strong>e change targets. Eachoptions will affect the Estuary’sprotected species and habit<strong>at</strong>s.However, The <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s believe thedecision should be taken on the basis of leastenvironmental damage and best costeffectiveness.In general the proposals cre<strong>at</strong>e three adverseimpacts, none of them well understood:1. Reduce upstream tidal range. This islikely to depress the productivity of themud-based food webs, affecting everythinghigher up the food chain – including people.Estim<strong>at</strong>es of intertidal habit<strong>at</strong> loss vary hugely,from 2,800ha (Tidal Fence) to 20,000ha(Cardiff-Weston barrage).2. Change the way sediment moves around.Different erosion and deposition p<strong>at</strong>terns arelikely to gre<strong>at</strong>ly alter the quality and extent ofmarine habit<strong>at</strong>s, and of the surrounding coast,but the Estuary’s physical processes remainlargely unstudied.3. Thre<strong>at</strong>en popul<strong>at</strong>ions of migr<strong>at</strong>ory fish.Estim<strong>at</strong>es of wh<strong>at</strong> the impacts might be arehampered by a lack of baseline d<strong>at</strong>a.Despite these uncertainties the Cardiff-Weston Barrage would, without question,have by far the highest environmental impact.The smaller barrages and two lagoon schemes(in their various forms) would be likely to havean intermedi<strong>at</strong>e impact. The SETS options(labelled in green below) would have thelowest impact.The Government’s own environmentalreport expresses low confidence in thepossibility of minimising the impacts of abarrage or lagoon development, and incre<strong>at</strong>ing compens<strong>at</strong>ory habit<strong>at</strong>. In fact itdescribes the chance of finding like-for-likehabit<strong>at</strong> elsewhere as ‘impossible’. Any habit<strong>at</strong>cre<strong>at</strong>ion, it admits, would have to be on an‘unprecedented’ scale.The <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s want to ensure thechosen option will not be something th<strong>at</strong>society regrets in decades to come.Twenty miles from thesea, the Severn Boresweeps upstream. Butfor how much longer?Wh<strong>at</strong> the acronyms meanSAC = Special Area of Conserv<strong>at</strong>ion cSAC = candid<strong>at</strong>e Special Area of Conserv<strong>at</strong>ionSPA = Special Protection Area Ramsar = intern<strong>at</strong>ionally important wetlandSimonwyndham.co.ukShortlistedShortlisted Shortlisted ShortlistedPREVIOUS PAGEBeachley BarrageSmallest barrage, lowest adverseimpact, but lowest energy potentialtoo. Loc<strong>at</strong>ed above the Wye, so fishpassage to SAC rivers still possible.Wholly within the cSAC, SPA andRamsar, so significant loss of habit<strong>at</strong>.Shoots BarrageCardiff-Weston BarrageFleming LagoonHabit<strong>at</strong> loss3500ha Habit<strong>at</strong> loss same or less thanHabit<strong>at</strong> loss5000haHighest energy and overall impact, Habit<strong>at</strong> loss20,000ha The longest structure, all of it in Habit<strong>at</strong> loss6500ha% within protected area 100% Fleming, but no fish passage to the % within protected area 100%with far more intertidal habit<strong>at</strong> loss % within protected area >95% cSAC. Impacts to migr<strong>at</strong>ory fish and % within protected area 100%Claimed power0.625 GW upper Severn and the Wye SAC. Claimed power1.05 GWthan <strong>any</strong> other option. Fish passage Claimed power8.64 GW freshw<strong>at</strong>er habit<strong>at</strong>s likely to be less Claimed power1.36 GWConstruction cost£2.3bn Wholly within the cSAC, SPA and Construction costs£3.2bnto all tributary rivers impeded,Construction costs £20.9bn than barrages, but would gre<strong>at</strong>ly Construction costs£4bnCO2 savings per year 0.7mt Ramsar, so significant loss of habit<strong>at</strong> CO2 savings per year 1.2mtleading to likely regional extinction of CO2 savings per year 7.2mt affect CO2 savings per year 1.0mtCost per unit of energy 12.6p/kWh Cost per unit of energy 10.4p/kWhCost per unit of energy 12.9p/kWh Eco-friendly erosion barrage and sediment applic<strong>at</strong>ion of the Spectral Cost per Marine unit of energy <strong>Energy</strong> Converter. 15.5p/kWhand disturbance during construction.Atlantic salmon and twaite shad.movements around the wall.Shortlisted SETS option SETS option SETS optionBridgw<strong>at</strong>er LagoonExtends across smaller proportion ofEstuary than Fleming Lagoon, solikely to have less impact on erosionand silt<strong>at</strong>ion. Impedes fish migr<strong>at</strong>ionto Rivers Parrett, Cary and Brue.Rel<strong>at</strong>ively low carbon saving.Habit<strong>at</strong> loss5000ha% within protected area 100%Claimed power1.36 GWConstruction costs£3.8bnCO2 savings per year 1.1mtCost per unit of energy 13p/kWhBy kind permission of Parsons Brinckerhoff By kind permission of Parsons BrinckerhoffTidal ReefLeast technically developed option,so estim<strong>at</strong>e for intertidal loss likely tobe less accur<strong>at</strong>e. Turbines likely toturn more slowly than in barragesand lagoons, posing a lower risk tofish. Large footprint is outside cSAC.Habit<strong>at</strong> loss8600ha% within protected area 0%Claimed power5 GWConstruction costs £18.7-19.8bnCO2 savings per year 5.6mtCost per unit of energy 20.3p/kWhBy kind permission of Parsons Brinckerhoff An artist’s impression © Evans Engineering, 2008Tidal FenceRel<strong>at</strong>ively low impact over a widearea. Partial barrier and low turbinespeed less harmful to migr<strong>at</strong>ory fish.Less impact on silt<strong>at</strong>ion/erosion too,due to constant flow. Largeconstruction footprint, outside cSAC.Habit<strong>at</strong> loss2800ha% within protected area 0%Claimed power1.2 GWConstruction costs £6.5-6.9bnCO2 savings per year 1.4mtCost per unit of energy 22.72p/kWhBy kind permission of Parsons BrinckerhoffBy kind permission of STFCSpectral Marine <strong>Energy</strong> ConverterA series of pillars supporting acauseway road. Structures in theHabit<strong>at</strong> lossnot known% within protected area not knownpillars use very high speed turbines Claimed power not knownFigure 5. SMEC Barrage Section is lowered into place between pre-driven sheet pilingcoffer to gener<strong>at</strong>e dams ontoelectricity. the pre-prepared Tidal terrace flow level is found<strong>at</strong>ion.ConstructionGaps aroundcostsand underne<strong>at</strong>hnot knowntheSMEC only Barrage partly impeded. Section are then D<strong>at</strong>a grouted. and Sections need CO2 only savings be joined per year <strong>at</strong> roadway not level, known asmore fully determined in detailed design.Cost per unit of energy not knownloc<strong>at</strong>ion not yet available.By kind permission of Parsons BrinckerhoffBy kind permission of Verd ErgNEXT PAGE20 The <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s’ Severn Estuary reportThe <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s’ Severn Estuary report 21

David Sl<strong>at</strong>erWh<strong>at</strong> kind of a worlddo we want to live in?It is time to understand th<strong>at</strong> we are part of n<strong>at</strong>ure, not outside of itStarlings <strong>at</strong>sunset, secondSevern crossingPREVIOUS PAGEWe are becoming more andmore aware of the impactswhich our everyday liveshave on the environmentin which we find ourselves.We must now take the next step: to realise th<strong>at</strong>yes, we are part of our ecosystem – not somesepar<strong>at</strong>e entity existing apart from the fish, thebirds, the worms and the mud.This understanding changes our idea of theworld we want to live in. Of course we needenergy – and the Severn Estuary presents anexciting and all too tempting option to providea large slice of the UK’s renewables. But wecannot view our energy needs in isol<strong>at</strong>ionfrom our environment. To do so could easilybe self-defe<strong>at</strong>ing. Why should this be so?As clim<strong>at</strong>e change takes hold, the changesin our environment are becoming ever moreapparent. We must therefore ensure th<strong>at</strong> ourenvironment is one th<strong>at</strong> can adapt to theseglobal changes, not decline under growingpressure. For this to happen we need to cre<strong>at</strong>eboth a Living Landscape and Living Seas – ourvision for the future.We often think of renewable energy asbeing environmentally-friendly. But if thewrong decisions are taken in the Severn – thewrong technology selected, in the wrongplaces – then renewable energy has thepotential to destroy all th<strong>at</strong> we rely upon.Th<strong>at</strong> destruction would not only affect theEstuary’s intern<strong>at</strong>ionally recognised wildlifeand habit<strong>at</strong>s. The shape and structure of theEstuary itself would change, and this couldhave serious consequences for our flooddefences. Then there are the ‘silent’ impacts –It is self-defe<strong>at</strong>ing to view ourenergy needs in isol<strong>at</strong>ion fromour n<strong>at</strong>ural environmentthose which will take time to become evident,some of which we simply cannot foresee.The <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s believe th<strong>at</strong> none of theshortlisted options is cost effective, and all fivecould destroy one of the most prized n<strong>at</strong>uralresources in the country. Whilst we recogniseth<strong>at</strong> the SETS options are still in their infancywe believe they demonstr<strong>at</strong>e the most promise.We have a moral and ethical oblig<strong>at</strong>ion toensure th<strong>at</strong> the least environmentallydamaging,most cost-effective option isselected. So we need to fully investig<strong>at</strong>e all theoptions, to make sure th<strong>at</strong> the technology isright for the job. Most of all we need to ensureth<strong>at</strong> decisions we take now, in the face ofclim<strong>at</strong>e change, are not ones th<strong>at</strong> we will liveto regret in years in come.The <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s believeth<strong>at</strong> a sustainable future canonly come from workingwith n<strong>at</strong>ural processes, notagainst themAndrew KerrNEXT PAGE22 The <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s’ Severn Estuary reportThe <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s’ Severn Estuary report 23

Wh<strong>at</strong> you can doCLICK HEREto see theSevern Estuary’swildlifehighlightsEmail or write to your MPExpress your concerns about taking the right decision, for the Estuary and peoplealike. You can find out who your local MP is by visiting theyworkforyou.com12Join our campaignKeep an eye on wildlifetrusts.org for further news and developments, and specificdetails of how to help.3VolunteerIf you would like to give your time to help The <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s’ campaign, pleasecontact your local <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong> (if you’re in Wales or the South West) or visit ourvolunteering pages on wildlifetrusts.org.4Enjoy the Estuary!Visit your local <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>’s reserves in the area, or simply get out and about inthe n<strong>at</strong>ural wonder th<strong>at</strong> is the Severn EstuaryEditor Rupert Paul. Layout editor Phil Long. Researcher Liz Walker. Project co-ordin<strong>at</strong>or Dr Lissa Goodwin. Printed by Fisherprint, Peterborough.Cover picture skyscan.co.uk. Back page picture David Woodfall. Copyright The <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>s 2010.References: P5: Loc<strong>at</strong>ion of options based on Department for <strong>Energy</strong> and Clim<strong>at</strong>e Change (DECC) d<strong>at</strong>a. P16/17: Ecosystem flow inform<strong>at</strong>ion by DrRick Park, <strong>Gwent</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> <strong>Trust</strong>. Severn facts: British Geological Survey 1996; Dargie, 2000. P18/19: bird migr<strong>at</strong>ion routes supplied by Mark Ward,RSPB. Salmon migr<strong>at</strong>ion route: CEFAS, also Tony Andrews, Atlantic Salmon <strong>Trust</strong>, www.nasco.int/sas/salseamerge.htm. P20/21: Shortlisted andSETS option performance d<strong>at</strong>a from DECC report.