Spider-Man's - Lighting & Sound America

Spider-Man's - Lighting & Sound America

Spider-Man's - Lighting & Sound America

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

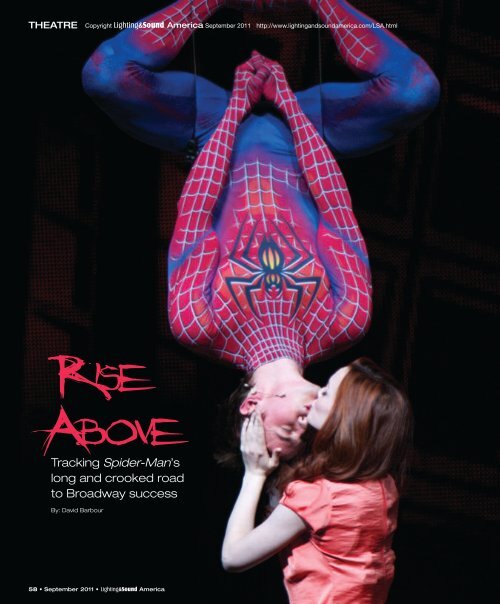

THEATRECopyright <strong>Lighting</strong>&<strong>Sound</strong> <strong>America</strong> September 2011http://www.lightingandsoundamerica.com/LSA.htmlTracking <strong>Spider</strong>-Man’slong and crooked roadto Broadway successBy: David Barbour58 • September 2011 • <strong>Lighting</strong>&<strong>Sound</strong> <strong>America</strong>

All photos: Jacob Colhpider-Man: Turn Off theDark finally opened onBroadway on June 14.Insert your own joke here.Or better yet, don’t. For in spite ofeverything—the ballooning budget,the delays and postponed openings,the swap-out of producers, theinjuries, the jokes by late-nightcomics, the New Yorker cover, thereplacement of key members of thecreative team— the unbelievable truthis that <strong>Spider</strong>-Man: Turn Off the Darkis looking more and more like a hit.Numbers don’t lie; since opening inJune, the musical has been doing nearselloutbusiness, routinely grossingapproximately $1.8 million each weekagainst a capacity of $1.9 million. If thebox office can keep up this torridpace—admittedly a big if—<strong>Spider</strong>-Manstands a chance of making back itsrecord-breaking budget of $75 millionin a couple of years. In any case, theshow’s producers aren’t sitting still;there’s talk of future productions,including a possible sit-down editionin Vegas and/or an arena tour. Thestory of <strong>Spider</strong>-Man, the musical, is farfrom over.Talk to members of theproduction’s design and technicalteam, however, and what you get isan enormous sense of relief. Thanksto the show’s many delays, most ofthem took part in a load/tech/previewperiod that extended over a full year.In addition to the stress of working ona show in a constant state of change,they’ve also faced an endless barrageof jokes, rumors, news reports,political pronouncements, the weeklyjeering of New York Post columnistMichael Riedel, and scathing word ofmouth from hard-core musical theatrefans venting in online chat rooms.And, as previews dragged on, they’vehad to frantically juggle theirschedules, postponing or cancellingpreviously made commitments.It’s all the more remarkable, then,that <strong>Spider</strong>-Man: Turn off the Darkhas emerged from its sometimeschaotic development process with aremarkably unified and effectivedesign. This is due in no small part tothose members of the creative teamwho stayed the course through allsorts of twists and turns. As a result,the sheer agglomeration oftechnology, coupled with a number ofinnovations, makes <strong>Spider</strong>-Man: TurnOff the Dark something of a must-seefor readers of this magazine. For suchambition, attention must be paid.To understand how the showarrived at its relatively happy ending,however, it is necessary to go back tothe beginning.The back storyIt began in 2005, when Julie Taymor,whose production of The Lion Kinglong ago entered into Broadwaylegend, and U2 front men Bono andThe Edge signed on do to a musicalversion of <strong>Spider</strong>-Man. (MarvelComics had announced its intentionto a <strong>Spider</strong>-Man musical as early as2002.) Taymor was to write anddirect; Bono and the Edge wouldprovide the score. Soon after,however, Tony Adams, the show’sproducer, died unexpectedly; hisassociate, David Garfinkle, took over,presiding over a budget that hadgrown to well north of $25 millionbefore it became clear that he hadn’tsufficiently capitalized the production.This occurred in the summer of 2009,and construction of the set and structuralwork on the Foxwoods Theatrewas halted, leaving the show in limbo.At this point, an executive shuffletook place, with control of theproduction shifting to Michael Cohl,formerly of the concert touring giantLive Nation and the producer behindU2’s touring spectacles, andJeremiah Harris, technical supervisoron dozens of Broadway shows andchairman/CEO of PRG, the globallighting, sound, scenery, and videocolossus. With new capitalization—and a budget that was nowreportedly $65 million—everyonewent back to work.By now, the original opening dateof February 18, 2010 was no longerviable. Evan Rachel Wood and AlanCumming, who were announced tostar respectively as <strong>Spider</strong>-Man’s loveinterest Mary Jane Watson and archvillainthe Green Goblin, departed.With their replacements, JenniferDamiano and Patrick Page, signed toco-star with Reeve Carney in the titlerole, the production was set to openDecember 21, 2010.As the world now knows, severalmonths of turmoil unfolded, astechnical delays caused multiplepostponements. A series of minorinjuries to cast members culminatedin the spectacular fall of ChristopherW. Tierney, one of several castmembers who stand in for <strong>Spider</strong>-Man during certain action scenes.(There are nine performers enacting<strong>Spider</strong>-Man’s stunts on stage at theFoxwoods.) As the show became anational talking point—there was evena New Yorker cover spoofing theseries of accidents that had plaguedthe show—and, as previews draggedon with no opening in sight, the NewYork press put down its collectivefoot, and most of the first nightreviewers attended a performance inFebruary, subsequently filing astunningly negative set of reviews.Seeking a way forward, theproducers removed Taymor, replacingher with Philip Wm. McKinley, who,among other things, has staged anumber of productions for RinglingBrothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus.Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa, an OffBroadway playwright who also writes<strong>Spider</strong>-Man for Marvel Comics, wasbrought in to rework Taymor and GlenBerger’s book; a new choreographer,Chase Brock, replaced DanielEzralow. After a short shutdownperiod, a new show emerged.Both versions of the show recounthow alienated teenager Peter Parkerbecomes <strong>Spider</strong>-Man, following a bitefrom a radioactive spider. In Taymorwww.lightingandsoundamerica.com • September 2011 • 59

figure who oversees Peter in times oftrouble and gently guides him tomaturity. (Gone is the infamous Act IInumber, “Deeply Furious,” depictingArachne and her eight-leggedfollowers on a shoe-shopping spree.)The Geek Chorus was eliminatedaltogether, a decision that vastlyimproved the production’s pace. Theextra time gained from these cutswas used to refashion the narrative,which now consists of a two-partbattle between <strong>Spider</strong>-Man and theGreen Goblin, and which focuses onPeter as he struggles to reconcile histwo identities.If anything, V2.0—as theproduction team calls it—relies moreon the show’s spectacle and flyingeffects, a decision that results in amuch stronger audience response.Taymor famously described <strong>Spider</strong>-Man as a combination of rock operaand circus, and that’s a pretty gooddescription of what is now takingplace on the Foxwoods Stage. If it’snot the show that anyone set out todo, it is, nevertheless, a show thataudiences want to see.In any case, another Broadwayshow with such ambitions is unlikelyto happen any time soon. Whatfollows is the story of how the designand technical team managed to riseabove (as one of the show’s songputs it) all the noise and negative buzzto accomplish their remarkable work.A comic book come to lifeGeorge Tsypin has designed sceneryat virtually all the major opera housesof the world. His productions for theMetropolitan Opera include War andPeace, The Gambler, and The MagicFlute, the latter staged by JulieTaymor. (The two have collaboratedon various projects.) On <strong>Spider</strong>-Man,he says, he and Taymor began with asingle simple concept out of whicheverything else evolved.“Clearly, we wanted to start withcomic books,” says Tsypin, whobegan designing the show in early2007. “I had never opened a comicbook in my life. I was surprised atwhat I saw, because it’s a differentway of reading. It’s so visual; in a way,you have to take in the entire page, asthere are so many events happeningat the same time. Comic books arealso very cinematic—you have a longshot followed by a close-up of thesame event. I wanted to capture theseperceptions in my design.”To create an on-stage world thatwas, essentially, a comic book cometo life, Tsypin deployed any numberof techniques, including flat illustratedbackdrops with big blocks of color,drops that open up like pop-upbooks, and plenty of video imagery.Scenes range from an intimate viewof Peter and Mary Jane on thelanding of a fire escape, floating in anight sky, to spectacularly sinistercityscapes, dominated by ominouslytilting skyscrapers, to a vertiginousdownward view from the top of theChrysler Building. (Much of Tsypin’sscenery has a strongly angularquality, which reflects his intensiveuse of forced perspective.)Tsypin notes that the show waslargely designed before the interregnumperiod that shut theproduction down for approximatelynine months. He says the long pause“was not a good thing for the show,but it was a good thing for us,because, during the hiatus, we hadthe chance to rethink certain things.We needed that extra time.” Theproduction’s scenery was built andautomated by PRG ScenicTechnologies. PRG also provided thelighting, sound, and video gear for theproduction, making it a total serviceprovider for <strong>Spider</strong>-Man.Among the issues with which thedesigner grappled were therelationship between the stage andauditorium, and the show’s extensiveflying system, which, he realized, hadto be integrated into the scenery. “Inan ideal world, I would have treatedthe entire theatre as one design,”Tsypin says. “Ultimately, I couldn’t bemore inclusive of the house.” Headds, however, that, with the show’slarge proscenium, which has the lookof a projecting spider web, “I createda tunnel that projects into the houseand psychologically sucks theaudience in; the barrier between thestage and the house is broken.”Of course, the flying effects arewhat really breach the normal gulfbetween stage and audience, andTsypin says he knew from thebeginning that <strong>Spider</strong>-Man wouldneed to fly. This mandateoccasionally complicated matters,however, as design ideas clashedwith the scale of the rigging set-up.“The original design had an upsidedownsubway train that ran above theaudience,” he says. “It was cut after itwas built, because of the complexityof the flying system. I had to clear agreat deal of space for it, and Icollaborated closely on it with theflying consultant [Jaque Paquin, whoworks frequently with Cirque duSoleil]; the set and the flying arebasically one design.“The big elephant is the integrationof the flying system,” Tsypin adds.“That’s what took so long. We had toconceive the logic of it. It’scompletely invisible—you see thewires, but not the superstructurebehind it. That steel structure has tobe 100% rigid; that’s why the theatrehad to be rebuilt.”PRG’s Fred Gallo, the production’stechnical supervisor, adds, “Anenormous part of the job was whatwe had to do to the theatre. We weredoing things with flying that hadnever been done before outside ofthe movies. Scott Fisher, of FisherTechnical in Las Vegas, did thesystem.” As opposed to oldfashionedflying systems, whichfeature a performer on a single cable,Gallo says, “When the actor in<strong>Spider</strong>-Man is flying over theaudience, he is tied to six differentwinches. There is one in each cornerwww.lightingandsoundamerica.com • September 2011 • 61

then, the pieces are kept in a bonded,climate-controlled warehouse. At thesame time, the theatre’s orchestraseating was removed to allow RogerMorgan, the theatre’s originalconsultant, to reseat the house formaximum capacity. The seats werekept out to allow the crew to workunencumbered.More fundamental structural workinvolved expanding and deepeningthe orchestra pit, in order to accommodatethe three scenic elevatorsrequired by Tsypin’s design. Thismeant digging into bedrock under thetheatre. Gallo, who hired a specialistcompany for the task, says, “The onlyeasy method was to use dynamite,but we weren’t allowed to do that.Instead, we had to use jackhammers.The New 42nd Street brought inengineers with strain gauges; if vibrationswere above a certain resonance,they’d shut us down. Work wastaking forever, so we brought in a big,construction-type jackhammer, whichis run independently by an operatorlocated 20’ away. That worked for acouple of months, then we brought indrills and hydraulic splitters to splitthe rock out.” After that, he adds,“We poured concrete to create a subbaseto put in the three lifts.”Also, says Gallo, “We took thetheatre’s stage out, which wasrelatively easy to do, as it was built tobe removed.” The trio of lifts in thenewly installed stage can createramps and platforms. “The ramps,which are trapezoidal, are 37’ long,and, when measured together, are 38’wide on the downstage side andapproximately 24’ wide on theupstage end,” he adds. “All of thestage ramps are hinged on thedownstage line. The center ramp hasan additional ramp built into it thatcan go up another 14’.” This addedarticulation reinforces the illusion offorced perspective that is usedthroughout the scenic design.“The first time you see this effect isin the Brooklyn Bridge scene,” saysPeter walks home from school. The drop behind him, depicting a set of row houses,turns like pages in a book to show the street from different perspectives.Gallo, referring to a nightmaresequence in which Peter dreams thatthe Green Goblin has kidnapped MaryJane. “<strong>Spider</strong>-Man is runningdownstage in slow motion as theplatform rises from the edge. Heleans out and Mary Jane is seenhanging from the underside of theramp.” The scene ends in a blackout.The stage ramps actuate up anddown, going up to a maximum heightof 14’, with a speed capacity from 0-14’, in under four seconds. “Since theramps had to move extremely fast, ahydraulic system was deemed theonly sensible way to go,” says Gallo.“We put in a hydraulic pump roomspecifically for this show and thenplumbed it with 4” diameter steel piperather than hoses, because of theamount of oil that had to be pumpedaround the building. This is thelargest hydraulic automation systemon Broadway.“We have 145 motorized effects inthe show,” adds Gallo. “A big musicaltypically has 50 or 60.” The scenery iscontrolled by two of PRG’sCommander automation consoles—one for scenery and one for deckeffects. “We have four automationtechs who run the show,” he says,“two who run all the Fisher flyingeffects in the followspot booth, sothey can see the stage, and two whorun PRG’s Stage Command Systemlocated on the stage right fly floor.”In addition, <strong>Spider</strong>-Man probablysets some kind of record for setelectrics, many of which will bediscussed a little later. However, oneparticularly notable item is the stagedeck, which, says Gallo, is an LEDlightbox. “I can’t tell you how muchdevelopment we went through withthat,” he adds. “We originallyimagined a lighting rig in thebasement, using incandescent units,which would shine through aPlexiglas deck. Eventually, weinvented our own LED lightbox.” TheLED units were designed by PRG andbuilt offshore.Much of the time, the stage deckis unlit. It is lit when, raised at anangle, the floor becomes part of theset for the climactic battle between<strong>Spider</strong>-Man and the Green Goblin(more about this later). “We spent alot of time researching the lighting forthe stage deck lightboxes in theramps,” says Mark Peterson, aproject manager for PRG ScenicTechnologies. “The Plexiglas tops arewww.lightingandsoundamerica.com • September 2011 • 63

THEATREdigitally printed on the underside inblacks and grays. The internal lightingnot only had to be white but it had tobe dimmable. There was no realdepth to be able to diffuse incandescentlighting properly, and therewould be too much heat. We decidedto design our own version of a white3” x 6” LED board, with LEDs on 1”spacing. This let us mount the LEDboards into different configurations tofit the trapezoidal lightboxes.Because they are so shallow, we onlyhad 2” available to diffuse the LEDs,so we mounted diffusion filtersdirectly underneath the printedPlexiglas panels. We provided 250LED dimmers to deal with theenormous amount of circuits neededfor the whole floor. Altogether, wehave about 9,000 LED boards in thefloor ramps.” These custom-designedLEDs are also used elsewhere, mostnotably in the eight LED panels thattraverse the stage.Of course, all of this requires plentyof power, which posed another set ofchallenges, says Randall Zaibek, oneof the show’s two production electricians(along with James Fedigan).“The theatre was equipped withseventeen 400A disconnects,” hesays. “Not that you would utilizeeverything in the theatre, but when wedid the math we had some issues.They had a 4,000A main disconnectfor the backstage feed, but we foundout from Con Ed that it was only beingfed with 1,200A. Between the lighting,automation, video, etc., the needs farexceeded the 1,200A feed. We wereestimating we needed around 4,000Ato run the show. Unfortunately, whatwe found at the street from Con Ed,which was on 43rd Street, was apotential 800A that we could bring intothe theatre, which would bring ourtotal power up to 2,000A for thebackstage feed. We got Con Ed togive us that extra 800A and goteveryone to rework their power needsso now we are running the show justunder the 2,000A being provided.”“Other than the show beingextremely heavy, it wasn’t a hard showto rig,” says Gallo. “But we have about125,000lbs of electrics and scenery inthe air, which puts us at the limit of thetheatre’s capacity. We had to install alot of secondary steel, and work withstructural engineers to ensure that wedidn’t overstress the building steel. Thefront-of-house flying requiredcantilevered secondary steel columns,structural bucking of the roof, anddiagonally bracing the roof trusses tocreate a stiff frame. Each fly line, afterexiting the winch drum, runs througheight to 12 different muling sheaves tofinally enter super gimbles, designedby Fisher in exactly the right location inthree-dimensional space. It was veryimportant that all of the ultimatepositions of the cable muling becorrect in three dimensions, as wewere providing three-dimensionalflying. The Fisher engineers worked outthe math for the software in advance,and were counting on us for accuracy.”Key momentsAlmost every scene in <strong>Spider</strong>-Maninvolves some scenic effects. Certainpieces recur throughout the show,including a spider web drop—the weboutlined in LEDs—that parts in themiddle to create a diamond iris revealeffect, and eight scenic legs, four eachat stage right and stage left, half ofwhich are lightboxes and half of whichare video panels. But scene after sceneyields many more visual surprises.It begins with the openingsequence, in which Peter Parker isThis nightmare sequence, set on the Brooklyn Bridge, makes use of the lifts built intothe show’s deck. Note also the cutout of the Green Goblin at stage left; it is one ofTsypin’s many comic-book touches.presenting a paper in his Englishclass on the topic of Arachne; thespider web drop parts to reveal whatis known in the production as theloom. In it, a number of Arachne’sfollowers, attached to vertical silks,swing from upstage to downstage. Asthey do, a series of horizontal silksrise into place, as if a giant tapestry isbeing woven on stage.“On the one hand, it’s a very simpleeffect,” says Tsypin. “You have girls onswings. But the geometry of it is verytricky. The horizontal pieces are timedmanually. The number of tests we hadto do was unbelievable. The horizontalpieces are silks, but the verticals are aspecial material that had to bedesigned, tested, and producedespecially for us. They had to becertified to carry that [human] load.”Next comes Peter’s high schoolclassroom, which Gallo calls “one of64 • September 2011 • <strong>Lighting</strong>&<strong>Sound</strong> <strong>America</strong>

the most difficult” pieces in the show.It’s a total pop-up effect; a backdropdepicting the school’s exterior comeson stage; an oddly angled section ofopens up vertically to reveal aclassroom interior. As that happens,four desks, created in forcedperspective, roll onstage. “It opens soquickly that you don’t realize whatjust happened,” he adds. “It’s like areal child’s picture book that opensup and all the desks unfold.”The following scene features aneffect that may not be the mostspectacular, but is, in some ways, themost astonishing. Peter and MaryJane are walking home from school.The actors are on a treadmill, and,behind them, a flat backdrop,depicting the row houses of Queens,executes a series of pivots, showingthe streetscape from various perspectives.“The Queens row houses are solightweight. They fly in and we havecounter-weighted jacks on the rear tooffset the weight of the panels asthey pivot. They end up working verywell,” explains Peterson. The scenealso features a whimsical inside joke:On the bridge that flies in above, atiny version of the No. 7 subway linepasses over the action. “I was toldthat the PRG scenic staff attached alittle figure to the train, and that figureis me,” says Tsypin, amused.Speaking of the scenery for thehigh school and Queens streetscape,Tsypin says, “Basically, I had one ideafor the show: the pop-up book. Icame up with it because Julie wantedto deal seriously with comic books.I’ve never done graphic designs in mylife—I always come up with complexspatial ideas—and somehow I had tocombine these two concepts. A popupbook does that; it gives you agraphic image rendered in space. Igot every pop-up book I could. Somany of them are so beautiful—and,to my horror, I realized how complexthey are. The people who do thesebooks are obsessives, maniacs—each one has to open in just such away. It took us months, but we finallystarted coming up with interestingpop-ups. Then the next issue was,how do you build them? I was told itwasn’t impossible—but, of course, Iwas working with PRG, and they werewilling to experiment.”Gallo notes, “I’d say to George,‘It’s not impossible, but it’simprobable that we can do this. I’dnever worked with George before,and I absolutely love the guy. Hedoes things totally differently. Mostdesigners sketch out what they’rethinking about and show it to thedirector. Then the assistants draft it ,specify it, and finally make a model.George does the opposite. He makes10, 12, 20 models until he is happywith what the design of the pieceshould look like. Then he has hisassistants draw it. He’s an architect;those models really helped us.”Speaking of the row house effect, headds, “It’s extraordinary, like a picturebook that keeps opening andopening. I can’t tell you how muchdevelopment went on in the shop toArachne tries to inspire Peter in the number “Rise Above.”www.lightingandsoundamerica.com • September 2011 • 65

THEATREget lightweight materials and to figureout where the motors should go.”In fact, a key part of the processinvolved finding lightweight materialsfor this and many other scenes. Thesolution was carbon fiber; many ofthe set pieces, which split open,unfold, or telescope out, are made ofcarbon fiber frames with fabricsstretched over them. As Gallo recalls,“George kept saying, ‘Freddy, build itlike a kite.’” As it happens, the PRGteam took that suggestion to heart.Gallo adds, “There weren’t manysolutions” to the challenges ofTsypin’s design. “Carbon fiber is usedfor fighter jets and the masts of largescalesailboats. We built a vacuummachine to make it; it was a wholenew way of working, but it was lightand stiff, and was what we needed.Of course, it’s so expensive it wouldmake your head spin around, but thisshow had the money to do it.”One scene where the use of carbonfiber proved crucial takes place themorning after Peter has been bitten bythe spider. He wakes up with his newsuper powers, as is demonstrated inthe number “Bouncing Off the Walls.”Peter’s bedroom consists of fourseparate pieces—two walls and aceiling and floor—that are held inplace partly by performers and partlyby rigging The walls, which are 18’wide by 14’ high, were fabricatedusing carbon fiber tubing and werecovered in spandex. Peter, rigged forflying, does just what the song’s titlesays, ramming into each of thesurfaces. “None of that could havebeen built normally,” says Gallo. “It’s alittle puppet theatre,” says Tsypin.“The actors are like puppeteers, andthey manipulate the walls.”In another example, an Act IIscene set in Mary Jane’s Manhattanapartment uses fiber frames with rareearth magnets that allow the walls tobe quickly assembled. “We areconvinced that future productions willbenefit from the experience wegained from this build process. Theuse of carbon fiber has opened newdoors of possibilities for us in scenicconstruction,” adds Peterson.Manhattan, as seen in severalsequences, including “Sinistereo,” inwhich the Sinister Six run amok, andin battles between <strong>Spider</strong>-Man andthe Green Goblin, has anExpressionist-meets-film-noir quality,reminiscent of some of Fritz Lang’ssilent films. The dark, claustrophobiceffect of these designs, with theiraskew angles and tricks ofperception, are aided by a set ofscenic sliders depicting skyscrapers,which the team refers to as the citylegs. “We have four sets of legs,which are large panels with citygraphics printed on the front, thatmove in and out and also light up indifferent colors,” says associatescenic designer Rob Bissinger. “Eachpanel moves independently and isable to not only track side to side, butalso tilt up to 45º, which gives usthese sweeping cityscapes.” Theissue in constructing these panelswas that, when backlit, the internalframing structure had to be effectivelyinvisible. PRG used the printedgraphic design on each panel’stranslucent facade as a kind ofcamouflage. The 2” aluminum rodswere welded to the internal channelframe in a unique pattern behind thedark lines of the printed graphic. “Wetried a lot of different techniques, withvarying levels of success,” saysBissinger. “Finally, they came up withthis kind of internal web-likestructure, which would actually helpkeep the legs plumb and square evenas they tilted and went off their centerof gravity. As these web frames insidethe legs catch little bits of light, theygive them an internal life and aninternal structure that is both <strong>Spider</strong>-Man-like and architectural.” Adding tothe vertiginous quality of thesescenes is an upstage circular piece,depicting skyscrapers, which spinsrapidly. “It’s just a way of referring tothe flying,” says Tsypin, but it adds tothese scenes’ disorienting, constantlyin motion effects.“I’ve never had an experiencewhere scenery moved so well,” thedesigner adds. “We were quite timidin the beginning, and programmedvery subtle movements. This isbecause I’m more used to opera, andI thought things had to move in morestately fashion. In most of thesescenes, you’re looking at the fliers,but the rapidly moving scenery doesadd to the excitement.”Probably the most talked-aboutscenic component is seen in theclimax, in which <strong>Spider</strong>-Man and theGreen Goblin meet for a showdownThe proscenium, as designed by Tsypin, is designed to pull the audience into the action.Its unusual angles made placement of the sound system more of a challenge than usual.66 • September 2011 • <strong>Lighting</strong>&<strong>Sound</strong> <strong>America</strong>

THEATREwhere the walls had to be so light.”Gallo adds, “We were rehearsingtwo shows—a regular Broadwayshow that happens on the stage andanother that takes place in the air.The show in the air takes more timethan it takes to rehearse a Broadwayshow on stage. It was a continuousfight to get enough time to rehearsetwo shows. That’s why we worked solong. It was eight in the morning tomidnight for months at a time; one ofthe hardest things about this showwas just being able to stick with it.”Villains in videoKyle Cooper, the projection designer,created the production’s original videocontent, much of which focuses on theGreen Goblin and The Sinister Six.Howard Werner, the production’smedia designer, says, “My job was towork with Kyle and Julie and George toincorporate the media into a Broadwayshow.” Ultimately, he was responsiblefor the final look of V2.0 Werner is aprincipal with the lighting and videodesign firm Lightswitch, and, he adds,“Lightswitch staff—including JasonLindahl, the production videoelectrician, and Phil Gilbert, the videoprogrammer—was in the theatre for 12months, full-time. I showed up inAugust, 2010 and worked until theopening in June. We were full-on insupport of the show from the momentthe video gear starting loading induring June of last year.”Cooper has directed more than150 film title sequences, his mostrecent releases include FinalDestination: 5, Rango, and the AMCseries The Walking Dead. In addition,he has done visual effects on suchfilms as TRON: Legacy and TropicThunder. He has provided either titlesequences or effects for most of thefilms based on Marvel characters,including all three <strong>Spider</strong>-Man films);he also designed the “flip-book” logothat is seen at the beginning of filmproduced by Marvel Productions. Andhe has considerable experience withJulie Taymor. “I worked with her onTitus Andronicus, and designed fivepenny arcade nightmare sequences inthe body of the movie,” he says. “OnAcross the Universe, I did second unitphotography and also the titlesequence. I did 300 effectssequences for The Tempest.”During the shooting of The Tempest,which was released at the end of 2010,Cooper and Taymor were well intodiscussions about projections for<strong>Spider</strong>-Man. He adds that their workingmethod was similar to that of theirfilms. “She will tell me her ideas, and I’llgo away and make books filled withstoryboard frames,” he says.“Sometimes they’re drawn, andsometimes they’re made of photomontages. I made a series of books for<strong>Spider</strong>-Man. For ‘Sinistereo,’ I did aseries of sequences showing, forexample, Rhino [one of the Sinister Six]crashing into the Leaning Tower ofPisa.” He notes that, in many ways, theinformation in the books was highlypreliminary. “Because the costumedrawings [by Eiko Ishioka] weren’tfabricated yet, it was hard to be morespecific, so we were kind of waiting. Imet with George Tsypin’s people andsaw designs for the set, but I didn’tknow what the costumes were going tobe. It was a little challenging.”Finally, Cooper says, “Thecostumes started to come together,and I went to New York with Julie andDanny Ezralow, and shot all of thevillains against green screens. Then Iput them into environments that wereinspired by what George was doing,and I began to show her frames ofwhat the video would look like.”The process of creating the videosequences was intensive, he adds. “Itseems really simple, but getting thesequences to the final product cansometimes be a long process. I knowJulie pretty well and we have workedtogether frequently, but still, to thisday, she surprises me with observationsthat she’ll make when I think Ihave it solved. Julie works harderthan anyone else. Her desire isalways to create something that hasnever been seen before, ‘a muse offire that would ascend the brightestheaven of invention.’ I have alwaysjumped at the chance to pursue thatmuse with her, regardless of thechallenges involved.”With the others, Werner played akey role in the selection of theprojection format. “At the point I gotinvolved,” he says, “there was thedesire for video projection; at the time,they thought they would use RPsurfaces. But, from a sanity-keepingpoint of view, LED panels were theway to go. At that point, however,they couldn’t really afford a high-ressurface. The delay in the showworked to our benefit because, duringthe time it was shut down, LEDproducts became less expensive.”The eight LED panels, each 8’wide by 33’ high, are configured asfour pairs of legs, which track on andoff stage. The 15mm SMD LED videoproduct is part of the custom LEDsspecified by PRG. The legs arecovered with black rear-projectionscreen to soften and blend the LEDimagery. In addition, they are coveredwith black sharkstooth scrim material;that way, when no video is displayed,they essentially disappear; when lit,they look like standard black fabriclegs. Each leg weighs 1,300lbs,contains 100 video tiles, and cantrack back and forth on stage in justabout any position. One image canbe spread across all eight legs, oreach leg can feature individualcontent. The majority of the videosequences take place in the secondact. During “A Freak Like Me NeedsCompany,” the legs show images ofthe Sinister Six, as, one by one, theyteam up with the Green Goblin.During “Sinistereo,” the legs showmore images of the Sinister Six asthey run riot. Later in Act II, whenPeter and Mary Jane go to a disco toforget their troubles, the legs arecovered with television images, which68 • September 2011 • <strong>Lighting</strong>&<strong>Sound</strong> <strong>America</strong>

The climactic battle, with aerial effects, is staged from the point of view of the top of the Chrysler Building, looking down at thetraffic below.are interrupted when the GreenGoblin jams the airwaves to issue anultimatum to <strong>Spider</strong>-Man. All of theseimages support Tsypin’s larger-thanlifecomic-book concept.“There was a lot of back and forthabout what comes first, the choreographyof the legs or my sequences,”says Cooper. “Also, there werequestions: Is the sequence locked tothe legs or does it move with the legs?Sometimes I had to reposition things.When I had to be back in LA, Howardwould be on the ground working withelements that I sent, speeding thingsup and color-correcting things interactivelywith Julie.”Feeding imagery to the legs arethree PRG Mbox EXtreme mediaservers—one for the eight LEDpanels; one for the projector mountedon the balcony rail, which is used forfront-projected effects; and one forpracticals onstage. There issomething like 320GB of content onthe servers, not all of which is used inthe show. The Mboxes are linked tothe production’s lighting console, aPRG V676. Werner used a similarapproach on the recent national tourof Dreamgirls, which also featured agreat deal of video content. “TheV676, which handles the video andthe moving lights, is linked to an ETCEos, which is the master,” he says,adding that there’s a MIDI ShowControl trigger for the video. He notesthat a significant number of videocues are linked to lighting cues. “If Ihave Video Cue 222 and Don Holderhas Light Cue 222, the V676 willautomatically take that cue number.We also coordinated with Don onvideo-only cues. When that happens,he creates a dummy cue in his cuestack; most of the time, however, Ihad something that would go alongfor the ride.” He adds, “There aresome moments when audio drivesthe bus. ‘Sinistereo,’ for example, islocked to the orchestra; there’s a clicktrack started by the conductor,associated with SMPTE time code,which triggers the video desk.”One major technical challengeinvolves allowing video content totrack with the LED legs as they movearound the stage. Thus the videosystem receives positioning informationfrom the automation systemthat drives the LED walls. Encodersadded to the SCS winches feed backeach video panel’s position to theMbox. That way, the automation andthe projection systems know exactlywhere the LED legs are at any time;this allows for quick and accuratemapping of video content while theLED legs are moving.PRG developed two modes for theMbox’s video output. In discretemapping mode, the video projectionwww.lightingandsoundamerica.com • September 2011 • 69

THEATREArachne’s loom is the first of the show’s many stunning effects.tracks with the LED leg as it moves,with the image appearing to beattached to the individual leg.Essentially, a single pixel of videooutput from the Mbox is mapped to asingle pixel on the LED output andtracks with the screen. In projectedmode, the output appears to beprojected onto the stage, notattached to the individual leg, butsimply allowing the legs to movethrough the projection. It’s possiblefor either mode to be set for eachindividual LED leg. “The way thatwe’re able to use content that thescreens move through, and contentthat is stuck to the screens, coupledwith front projection in and aroundthe LED screens, really gives us avideo composition with a lot ofdepth,” says Lindahl. “It allows us tolayer video content in a number ofdifferent ways; to create many veryvisually striking and unique looks thatmaybe haven’t been seen before on ascale of this size.”Then came the job of implementingV2.0 which, thanks to asignificantly different second act,required considerable reworking ofthe video sequences. By then,Cooper, who oversees a busy firm of70, had returned to Los Angeles. “Idelivered all my sequences and theyseemed immutable at that time,” hesays. Julie left me a message thatsomething was going on. ThenHoward called me and said he’d[been asked by the producers to]make changes that they needed tomake to my sequences.” Werneradds, “My job on V2.0 was to recompositethe footage. For example, ‘AFreak Like Me Needs Company’ is anall-new sequence.”Werner says that collaborating withHolder was a real necessity. “Wecoordinated everything; there aremoments when video is the key visualelement—and if there’s a colorscheme happening in the video, Donplays along. In the first act, video issecondary; in the walking-homefrom-schoolsequence, the LED legsare used only to make fields of color.Don set the colors he wanted to useand I went along with it. The part thatworks the best is in moments whenyou don’t know which technologyyou’re looking at.”Ubiquitous lighting“It was a process I will not forget,”says Donald Holder, who beganworking on the show’s lighting designin 2007, moving into the theatre in thesummer of 2009. “Randy Zaibek andhis crew were just about to beginprepping the lighting and doing thepre-hang, and, on August 4, 2009—Iremember the date—they pulled theplug. We started back up in thespring of 2010, and everything movedreally quickly after that. All of asudden, I had a six-monthcommitment—and then it gotextended another six months.”By any standard, Holder’s taskwas enormous, as he was required tonot only light the action onstage, butalso above the audience—and, as wehave seen, the production features adaunting number of set electrics.Even so, finding space for lightingwas the issue, what with all the realestate taken up by the flying rig andscenery, and considerable ingenuitywas required to allow Holder to do hiswork. “Most of the drops measureabout 50’ tall by 70’ wide, and had tobe lit absolutely evenly from top tobottom,” he says. “The only way toaccomplish this task was to light thegoods from directly behind. We hadroom on the back wall, so I designeda massive goalpost system fitted withAltman Spectra Cyc LED lights,[Philips Vari*Lite] VL2000 Wash lights,and [Martin Professional] AtomicStrobes. They all shoot through amuslin drop that acts as a bounceand as a diffuser, focusing directlyonto various goods: a rear-projectionscreen that’s used as the cyc, theOscorp Laboratory drop, the revengedrop, etc.” With this system, themuslin bounce can fly out, allowingHolder to light directly through thedrops when he wants to see thesources. For example, the OscorpLab features a yellow sun; when, inthat same scene, Norman Osbornebecomes the Green Goblin, the transformationis effected using Atomicstrobes from the goalpost. During thenumber “If the World Should End,”featuring Peter and Mary Jane on thefire escape, there’s an effect with lightstreaming through a pinhole drop,70 • September 2011 • <strong>Lighting</strong>&<strong>Sound</strong> <strong>America</strong>

creating a starry-night effect withmoving beams of light. “I use VL2000Wash lights mounted on the backwall goal post, programmed to slowlyscan across the rear of the pinholedrop,” says Holder. “It’s an incrediblysimple idea but very effective.”Given the demands of scenery andrigging, Holder was dealing with alight plot that had to be fit into anyavailable space. Thus the rig istrimmed at over 40’ over the stage,because the fixtures must bepositioned above the fly wires. In thehouse, followspots are necessary totrack the flying sequence; however,the theatre’s traditional followspotpositions were no good, because theunits had to reach from one end ofthe theatre to the other. This meantthe installation of new positions forthe show’s three Lycian M2 units. “Ithink of the followspots as the firstlayer of the flying lighting,” saysHolder. “They can follow the flyinganywhere in the theatre, and they areincredibly helpful. The second layerinvolves tracking the flights withautomated lights using positioningdata received from the flying system;finally, we put in the infrastructure sothat the entire space is illuminated. Inthe end, most of the flying sequencesuse a combination of all threetechniques.” In other scenes, headds, other techniques must be used:“In ‘Bouncing Off the Walls,’ we have[ETC] Source Four 10° units withhand cranks for the scrollers; thestagehands stand in the wings,operating them. We use this sameapproach to light the all of theonstage flights, including whenArachne is flying. Three followspotsisn’t that many for a show of this size;with these auxiliary units, we’re prettywell covered.”Holder adds, “Overhead positionsare very limited because of sceneryand rigging; the bulk of the overheadplot is composed of automatedlighting. This is the largest movinglight rig I’ve ever used—because thedemands of the production are soimmense and space is so limited.There are about 160 units, and they’respread all over the theatre. As theshow kept evolving, Julie kept askingfor a cool white HMI light on theactors—and that limited the use oftypical tungsten halogen fixtures. Thearc sources became more important,because those units give off the kindof light she was looking for.”Of course, as noted, Holder had towork intensively with Tsypin and PRGstaff on set electrics. Speaking of thecity legs, Mark Peterson says, “Therequirements were endless. Eventhough they were to be built as lightboxes,they could not be too deep,front to back. They had to be internallylit with RGB color, and alsoindividual windows in the front panelgraphics had to be able to be lit andcontrolled. Also, the rear had to beable to be backlit with automatedlights, which also meant there couldbe no shadows from internal framingneeded to prevent twisting ortorqueing. It was both a lighting andscenic challenge.” Holder adds, “TheCity Legs are only 6” deep, but 9’wide and 40’ tall. I’ve lit enough lightboxesto realize that it would bedifficult to provide even lighting witha range of vivid colors. We didseveral mockups at PRG. We triedmini-strips, but they wouldn’t fit inthe space. We looked at LED fixtures,and decided on Philips Color KineticsColorGraze units. However, theydidn’t solve the problem completely,because there were times the centerof the box would be dark, becauseyou couldn’t get the light throughsuch a narrow opening. I needed tobacklight the legs as well.” Petersonadds, “For the overall RGB lighting,we ended up using ColorGraze linearunits, which had a nice, tight beam of10° x 60°. We ringed the inside of theCity Legs with the ColorGrazes andgot a nice even light with noscalloping. The window lighting wasa little more complicated, but wefound single LED puck lights andmounted them on round ½”aluminum rods; we positioned themwhere the windows were and weldedthem into place.”Holder seconds Werner’scomments about the color-matchingprocess used to unite lighting andvideo. “Howard and I had a very goodcollaboration, making the lighting andvideo work together, especially in ‘AFreak Like Me,’ which is about usingan iconic color for each super-villain.A lot of the lighting and the videocues are driven by the same console.It was a very intense and involvedcollaboration. It was overwhelming attimes, trying to figure it out. Whenyou see the end result, it doesn’t lookcomplicated—it seems prettyeffortless and transparent—but it tooka lot of work to get it there.”Holder and his team, includingassociate lighting designer VivienLeone, wrote over 600 cues. ThePRG lighting package includes morethan 1,800 focusable fixtures, with157 automated fixtures, 554 LEDfixtures, and over a quarter mile oflinear LEDs. There are 551 ETCSource Fours and Source Four PARsin various models and degree sizes,two Strand 8” Fresnelites, 18 twocellfocus cycs, sixteen 9LT T-3striplights; thirty-one 6” MR16 striplights,six 2’ MR15 Vegas strips, 250MR16 units of various types, threeLycian M2 followspots, 16 Mini-Tens, 20 Micro Fill units, 113Wybron Coloram II scrollers, and 17Wybron CXI scrollers. For effects,there are four C02 jets, four confetticannons, four High End Systems AF1000 strobes, 19 Martin ProfessionalAtomic strobes, eight DiversitronicsMighty Lite strobes, eightDiversitronics Superstar strobes,three MDG Atmosphere hazers, fourMDG MAX 3000 foggers, two LookSolutions Power Tiny foggers, twoScotty 2 foggers, 11 Look SolutionsViper smoke machines, one Bowenfan, seven Martin Jem fans, and onewww.lightingandsoundamerica.com • September 2011 • 71

THEATRE28” wind machine. The moving lightcomponent includes six CoemarInfinity Wash XLs; 27 PhilipsVari*Lite VL3500Qs, ten VL3500Wash units, 22 VL2000 Wash units,two VL2500 Spots, three MartinProfessional MAC 2000 Wash XBs,40 Mac 2000 Performances, 27 Mac700 Profiles, six High End SystemsStudio Colors, and 14 DHA DigitalLight Curtains. The LED componentincludes 56 Altman Spectra Cycs,eight Altman Spectra PAR 100MFLs, 12 Philips Color KineticsiColor MRs, 70 Philips CK 12”iCoves, four 6” iCoves, 90 CKColorBlast 12s, seven CKColorBlaze, 312 CK ColorGrazePowercore strips in various sizes, 91LED MR16s, 15 LED RGB LightTape, 535 LED nodes for the deck,147 Endor 7007 LED nodes, BocaFlasher LSS30xx strips and SMX006LED modules, CK EW MR16 unitsand EW SLX strands of LED nodes,one Neoflex LED tube, 31 miscellaneousLEDS from LEDtronics, andtwo Suberbright Flex LED strips.Discussing certain aspects of therig, Holder says the Mac 700s “aresmall and fast; they illuminate a lot ofthe flying. They’re very facile units;they can accelerate quickly and theirmovement pattern is always smooth.He also notes that the Coemar unit“became very important. It’s like a1,500W ACL, with very rich colorproduction; I use it to do big strongslashes of light in the air.” TheVL2000 washes, he adds, “are usedto backlight many of the drops andthey illuminate the starscape in ‘If theWorld Should End.’ These wash unitsalso animate the text on the “revengedrop,” [lighting up words like “pow!”]in ‘Bouncing Off the Walls.’”Speaking of control, Holder says,“We used the first 20,000-channel[ETC] Eos console for the conventionallighting, mostly for the LEDs.The automated lighting is controlledby a PRG V676, which is alsodriving the video system. We usedtwo V676s during the cueing, andnow one console runs both lightingand video. Richard Tyndall, whoprogrammed the lighting, didsomething that shocked somepeople. People ask me, ‘How didyou light all the flying? Was theresome sophisticated trackingsystem?’ Actually, Richie did it withhelium-filled party balloons. Werealized we’d get no time to light theactors, so, using the flight data fromFisher, he figured out the flightpaths, their acceleration and deceleration,and, at each point along thepath of travel, Richie, aided by hisassistant, Porsche McGovern, wouldcreate presets for all the appropriatemoving lights. These presets wereused to create a complex series offollow cues, and then it was amatter of finessing each step alongthe path until it resulted in a smoothand continuous pattern ofmovement. At its core, it’s a fairlysimple solution; there were days anddays of party balloons.”Somehow, during <strong>Spider</strong>-Man’stumultuous winter, Holder managedto light two more Broadway shows,Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia and StephenAdly Guirgis’ The Motherf—ker withthe Hat. This was possible, he says,because “after February 7th, theshow went into a state of inertia”while its future was being worked out.He adds, “I had a day and a half totech Arcadia, and a week and a halfof previews—after working on a showthat teched for two months, it wasreally thrilling.” Then, when Taymorexited and McKinley took over,Holder, a longtime Taymor collaborator,experienced feelings of dividedloyalties. Ultimately, he says, “Iwanted to see it through; that wasvery important to me.”Holder quickly learned that thelighting approach he had devised forTaymor’s vision—with lots of coolHMI lighting on the actors, set againstbackgrounds of deep color—didn’t fitwith McKinley’s approach. Thedesigner adds that he worked withMcKinley on the hit musical The BoyFrom Oz, “so we had a workingvocabulary.” Overall, he says,McKinley “wanted the lighting to beless cool and edgy and more texturedand colorful. I had to smooth out theedges, making it softer, lighter, andmore kid-friendly. At first, I was takenaback; I thought, how can I do this?We had taken a very specificapproach, and it was hard to acceptthe direction show needed to take.Thinking about it, reading the newscript, and seeing it on stage, Irealized I had to get with theprogram. But if I told you it was easy,I wouldn’t be honest. On some level, Ididn’t want to mess with Julie’s work;ultimately, I tried hard to be a conscientiouscollaborator.”However, he adds, “I feel goodabout what we did. I feel that wehave a strong point of view, visually,and, on many levels, we help to tellthe story. We went in there every day,trying to do the best work wepossibly good. It was frustrating anddisappointing at times, and it wasn’talways easy to stay motivated. Theshow was expensive for a lot ofreasons, but we never veered off thepath of what the design needed tobe. The sheer amount of technologyin the production is overwhelming,but I don’t feel there’s anything in theshow that we didn’t really need to dothe job.”<strong>Spider</strong>y soundIn some ways, despite all thecomplex technical challenges listedabove, sound proved to be the mostdifficult aspect of <strong>Spider</strong>-Man,especially since the early, unauthorizedset of reviews complained thatthe production was, at times, hard tohear. This seemed almost impossibleto believe, as the production’s sounddesigner, Jonathan Deans, hadworked fruitfully in the FoxwoodsTheatre several times before, on suchshows as Ragtime, The Pirate Queen,72 • September 2011 • <strong>Lighting</strong>&<strong>Sound</strong> <strong>America</strong>

and Young Frankenstein. (You couldargue that Deans’ shows were theonly intelligible productions in ahouse that another sound designeronce described to this magazine as“an absolute sonic disaster.”) Deansdeparted the production, early in2011, to work on another Broadwaymusical, Priscilla, Queen of theDesert. Peter Hylenski, a formerDeans assistant and a designer withmore than a dozen Broadway showson his resume, took over. As SimonMatthews, who worked as <strong>Spider</strong>-Man’s production sound engineerbefore leaving to take a full-time jobwith Meyer <strong>Sound</strong>, notes, the road togetting an effective sound systemwas a rocky one.Interestingly, Matthews says, inone respect, the job of the sounddesign team was made easier. Thepre-load-in structural work includedthe removal of the proscenium headerand parts of the ceiling dome, architecturalelements that in the pasthave proven to be acousticalobstacles. But the scenic design andflying rigging system posed newchallenges that weren’t easily solved.“In Version One, we had three thingsgoing against us,” he says. First,unsurprisingly, was the battle forspace. “Everyone needed somethingin every location. The flyingdepartment needed landingTsypin’s set for the Oscorp Laboratory has an inside-the-test-tube feel; it also has oneof the show’s two bridges. The set’s “sun” is a backlit effect created using the goalpostinstalled upstage by Holder.platforms. The lighting departmentneeded positions for side light.” Headds that everyone strove to accommodateeveryone else, but, at times,solutions were hard to find. “There’sso little room behind the proscenium;in some spots, its 6’ off the wall—and, in some spots, it’s 6”. Also,when you look at the house leftproscenium, you don’t see that onepart of it has a fairly substantial pitchcoming out into the house. I asked ifwe couldn’t hang speakers off ofthat—but, if we did, the speakerwould be shooting 20’ in the wrongdirection. If we had been hanging asmall trapezoidal cabinet, it mighthave been all right, but we werehanging a line array.”This, Matthews note, was thenature of the game: “We spent a lotof time negotiating what little spacethere was on the proscenium. We hadseveral versions of plans; we’d hangboxes, then something else wouldcome along and they wouldn’t workin those positions. That is the natureof this type of production; it’s aninstallation and you just have to rollwith it.”The second issue was Tsypin’shighly dimensional proscenium,“Because of its angles—and thestructure placed behind it to holdthose angles in place, there was noroom to put loudspeakers. Where youcould put them, they wouldn’t beaudible to the audience. There’s notmuch magic to sound; if the speakersaren’t visible, they won’t be audible tothe audience.” The third issue, hesays, was that the proscenium wascovered in what he describes as “aperforated RP material, like, say, aperforated shower curtain. “Somematerials can be used withoutimpacting the sound,” saysMatthews, “but not this.” He addsthat, by the time it became clear thatthere might be a problem, “some ofthe scenery was already built. At thatpoint, you can’t say, ‘That’s impossible.’You have to fix it in thetheatre.” Ultimately, he says, after ademo that proved how much thesystem could be improved, thespeakers were brought out frombehind the proscenium, with many ofthem being retained in floor positions.Even so, it’s a very tight fit.From the beginning, he says,Taymor’s vision involved three distincttreatments of sound. “There was thetheatrical world of the maincharacters; the astral plane, whereArachne lived and which wassupposed to have a floating,surround-sound feeling; and thesuper-hero scenes, which waswww.lightingandsoundamerica.com • September 2011 • 73

THEATRE<strong>Spider</strong>-Man flies in front of Tsypin’s sinister, angled, Expressionistcityscape.The flying effects send the performers into the auditorium.supposed to be very rock ‘n’ roll.”This idea, coupled with the show’soriginal orchestrations, made thechallenger harder: “We put in a set ofpitch and delay effects in the scenewith Arachne’s loom; it was okay, butthey wanted to hear every word.”Similarly, he says, in one of the GeekChorus scenes, “the characters hadthree brief lines, but there was also ahorn fanfare going on.” Ultimately, headds, “I think we did nine real systemdesigns, apart from various smallchanges and tweaks.”The show’s main prosceniumsystem consists of Meyer <strong>Sound</strong>M’elodies—eight per side at left andright—with Meyer JM-1Ps in a centercluster made up of two rows of four.Originally, says Matthews, “Meyer<strong>Sound</strong> MICAs (for the sides) and L-Acoustics v-DOSC (for the center)were specified, but the latter didn’twork well with the prosceniumstructure and, as the system wasrevised, the Micas weren’t available,so we went with the M’elodies.”Anyway, he says, “The M’elodieswere the smallest boxes we could putin there and pull it off. We knew theyhad enough punch for a theatricalevent.” The surround system featuresd&b audiotechnik E8s, with more ofthe same units used in underbalconypositions; Meyer UPJs fill out thesurround system. Overhead are eightMeyer CQ-2s, with UP jrs providingside and cross fill, and M-1Dsproviding front fill.Because the orchestra pit containsscenic elevators, the band, whichconsists of 18 musicians, is found intwo locations. “The live room, whichis off the trap room—formerly thegreen room—houses the strings andhorns. The core band room, withguitars, basses, percussion,keyboard, and a monitor mixer, is inthe basement down the hall, on thestage-right side.” This decision wastaken after many other avenues wereexplored and rejected. At differentpoints, the band was going to belocated in the house, on two sides ofthe room; in another scenario, theguitars and drums were to be placedin the proscenium header. Other ideashad the drummer in a plenum behindthe house left proscenium leg orsuspended in a glass box over thehouse left exit door. During VersionOne, the guitars occupied a spot infront of the proscenium at stage right,but this arrangement was dropped inVersion 2.0.]Because of the musicians’isolation, says Matthews, “We wentthrough a number of iterations,looking for video monitors to allowthem to see each other and theaudience. We tried several things andwent back to CRT projectors. Peoplewanted bigger screens, so weinstalled 42” LCD screens. We have aBarco Image Pro to convert theimage from its native resolution to fitthe screens.” He adds that themusicians can see the audience, anda set of four mics in the auditoriumfeed the audio to both band rooms,each of which has a pair of speakersand a sub. In addition, the musicianshave Aviom personal monitor mixers,“because some numbers are on atempo clock. There’s one click trackwith vocals, but the rest aremetronome clicks that give them thefirst eight bars of a song.” This isnecessary, he adds, to keep everyonestrictly in tempo during the flyingsequences, which are cued to themusic. Also, he says, “The Edge’sguitar style uses a lot of delay effects,and they need to be timed to themusic as well. The guitar players—who are phenomenal—spent a lot of74 • September 2011 • <strong>Lighting</strong>&<strong>Sound</strong> <strong>America</strong>

time working on this style.” He notesthat the guitar players use a FractalAudio Systems Axe-FX all-in-onepreamp/effects processor: “Everyoneis really impressed with it. You cansay, ‘I want this pedal and this brandof amplifier head,’ and it’s truthful.Prior to this, a model guitar boxsounded like a model guitar box. Thiswas the first I’ve heard that can reallyfool your ears.”The entire cast is on boom mics,says Matthews, citing what he callsSimon’s Law of Center: If you wantthe ultimate reinforcement, the micmust be as close to the performer’smouth as possible. Commenting onthe typical Broadway practice ofputting mics at the center ofperformer’s foreheads, he says, “Nosound comes from there.” The micsystems are Sennheiser, with SK5212wireless systems, 3732 receivers andHSP-2 capsules.<strong>Sound</strong> is controlled by a MeyerCue Console, which features the firstmajor D-Mitri system used in NewYork. “We needed the recallability andfunctionality that we had becomeaccustomed to in LX300 products,”he says, mentioning the CueConsole’s previous effects engine.“So we took the plunge and said,‘Let’s get D-Mitri.’ It’s prettyawesome. Although it’s a magnitudeof order more complex in many ways,it programs in much the same way asthe LX300. We also do speakermanagement using five [Meyer]Galileo processors.” The D-Mitrisystem also includes 48 tracks ofplayback for sound effects. The onstagemonitor mix is generatedthrough the front-of-house console.As you might imagine, communicationis a critical issue in <strong>Spider</strong>-Man, and the show makes use of aClear–Com Eclipse system. “Thereare two stage managers calling theshow—one for scenery and flying andone for lights,” he says. “The first ofthem needs to be able to communicatewith a great number of people;he has the hot button, whichconnects to anyone in the show whoflies, via in-ear receiver. These are thenavigator cues; he’ll say, for example,‘Navigator 300 and go,’ and theperformers know that they’re about togo to flight. With their in-ears, theyclearly hear the stage manager callthe cue. To conceive of that withoutthe Clear-Com system would be verydifficult; it gives you enormous flexibilityand capacity.” Also used areTelex TR-82N wireless belt packs anda Clear-Com Cellcom system.Like everyone else involved in<strong>Spider</strong>-Man, Matthews says that thelong hours and uncertain productionschedule took their toll. “Everyonehad to figure a way to deal with theprocess,” he says. “I’m surprisedeveryone worked together as well asthey did.”Aside from those mentioned inthe above text, productionpersonnel include Hilary Blanken, ofJuniper Street Productions(production management); C.Randall White (production stagemanager); Kathleen E. Purvis (coproductionstage manager); SandraM. Franck, Andrew Neal, JennySlattery, and Michael Wilhoite(second assistant stage managers);Theresa A. Bailey, Valerie Lau-KeeLai, and Bonnie Panson (sub stagemanagers); Rob Bissinger (associatescenic designer); Arturs Virtmanis(pop-up and dimensional design);Baiba Baiba (illustration andgraphics); Sergei Goloshapov(cityscape graphics); Anita La Scala(first assistant set design); SiaBalabanova and Rafael Kayanan(assistants, graphic art); NathanHeverin (assistant, pop-ups); EricBeauzay, Catherine Chung, RachelShort Janocko, Damon Pelletier, andDaniel Zimmerman (model makers);Robert John Andrusko, Toni Barton,Larry W. Brown, Mark Fitzgibbons,Jonathan Spencer, and Josh Zangen(draftsmen); Tijana Bjelajac, Szu-Feng Chen, Heather Dunbar, MimiLien, Qin (Lucy) Liu, RobertPyzocha, Chisato Uno, and FrankMcCullough (assistant set design);Lily Twining (previsualization); VivienLeone (associate lighting designer);Caroline Chao, Carolyn Wong, andMichael Jones (assistant lightingdesigners); Porsche McGovern(assistant to the lighting designer);Richard Tyndall (automated lightingprogrammer); Sarah Jakubasz(assistant video designer); PhilGilbert (video programmer); BrianHsieh and Keith Caggiano (associatesound designers); Jason Shupe(automated flying programmer); JackAnderson (production carpenter);Andrew Elman, Dave Fulton, HughHardyman, Kris Kenne, Matthew J.Lynch, Mike Norris, and GeoffreyVaughn (assistant carpenters);Randall Zaibek and James Fedigan(production electricians); RonMartin (head electrician); JasonLindahl and Chris Herman(production video electricians),John Sibley (head sound engineer);Dan Hochstine (assistant soundengineer); Joseph P. Harris, Jr.(production properties supervisor);Timothy M. Abel (associateproperties supervisor); and MartinGarcia, Gonzalo Brea, and ThomasAndrews (E-stop personnel).Other contributors includedExcitement Technologies (specialeffects); I. Weiss and Sons (softgoods); the Spoon Group, theRollingstock Company, ParagonInnovation Group, Illusion Projects,Beyond Imagination, Cigar BoxStudios, and Hamilton ScenicSpecialty (props). Puppets wereexecuted by Nathan Heverin, MichaelCurry Design, Paragon Innovation,and Igloo Projects.All of them have managed tosurvive the most crushing andnotorious preview period in thehistory of Broadway. Whateverhappens next, they—and <strong>Spider</strong>-Man—have entered the Broadwayhistory books.www.lightingandsoundamerica.com • September 2011 • 75