7. Historical Infinitive - VU-DARE Home

7. Historical Infinitive - VU-DARE Home

7. Historical Infinitive - VU-DARE Home

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

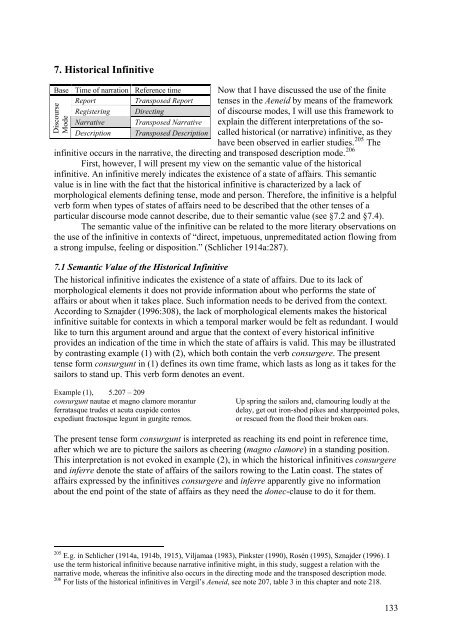

<strong>7.</strong> <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Infinitive</strong><br />

Base Time of narration Reference time<br />

Report Transposed Report<br />

Registering Directing<br />

Discourse<br />

Mode<br />

Narrative Transposed Narrative<br />

Description Transposed Description<br />

Now that I have discussed the use of the finite<br />

tenses in the Aeneid by means of the framework<br />

of discourse modes, I will use this framework to<br />

explain the different interpretations of the socalled<br />

historical (or narrative) infinitive, as they<br />

have been observed in earlier studies. 205 The<br />

infinitive occurs in the narrative, the directing and transposed description mode. 206<br />

First, however, I will present my view on the semantic value of the historical<br />

infinitive. An infinitive merely indicates the existence of a state of affairs. This semantic<br />

value is in line with the fact that the historical infinitive is characterized by a lack of<br />

morphological elements defining tense, mode and person. Therefore, the infinitive is a helpful<br />

verb form when types of states of affairs need to be described that the other tenses of a<br />

particular discourse mode cannot describe, due to their semantic value (see §<strong>7.</strong>2 and §<strong>7.</strong>4).<br />

The semantic value of the infinitive can be related to the more literary observations on<br />

the use of the infinitive in contexts of “direct, impetuous, unpremeditated action flowing from<br />

a strong impulse, feeling or disposition.” (Schlicher 1914a:287).<br />

<strong>7.</strong>1 Semantic Value of the <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Infinitive</strong><br />

The historical infinitive indicates the existence of a state of affairs. Due to its lack of<br />

morphological elements it does not provide information about who performs the state of<br />

affairs or about when it takes place. Such information needs to be derived from the context.<br />

According to Sznajder (1996:308), the lack of morphological elements makes the historical<br />

infinitive suitable for contexts in which a temporal marker would be felt as redundant. I would<br />

like to turn this argument around and argue that the context of every historical infinitive<br />

provides an indication of the time in which the state of affairs is valid. This may be illustrated<br />

by contrasting example (1) with (2), which both contain the verb consurgere. The present<br />

tense form consurgunt in (1) defines its own time frame, which lasts as long as it takes for the<br />

sailors to stand up. This verb form denotes an event.<br />

Example (1), 5.207 – 209<br />

consurgunt nautae et magno clamore morantur<br />

ferratasque trudes et acuta cuspide contos<br />

expediunt fractosque legunt in gurgite remos.<br />

Up spring the sailors and, clamouring loudly at the<br />

delay, get out iron-shod pikes and sharppointed poles,<br />

or rescued from the flood their broken oars.<br />

The present tense form consurgunt is interpreted as reaching its end point in reference time,<br />

after which we are to picture the sailors as cheering (magno clamore) in a standing position.<br />

This interpretation is not evoked in example (2), in which the historical infinitives consurgere<br />

and inferre denote the state of affairs of the sailors rowing to the Latin coast. The states of<br />

affairs expressed by the infinitives consurgere and inferre apparently give no information<br />

about the end point of the state of affairs as they need the donec-clause to do it for them.<br />

205 E.g. in Schlicher (1914a, 1914b, 1915), Viljamaa (1983), Pinkster (1990), Rosén (1995), Sznajder (1996). I<br />

use the term historical infinitive because narrative infinitive might, in this study, suggest a relation with the<br />

narrative mode, whereas the infinitive also occurs in the directing mode and the transposed description mode.<br />

206 For lists of the historical infinitives in Vergil’s Aeneid, see note 207, table 3 in this chapter and note 218.<br />

133

CHAPTER 7<br />

Example (2), 10.299 – 302<br />

quae talia postquam<br />

effatus Tarchon, socii consurgere tonsis<br />

spumantisque rates aruis inferre Latinis,<br />

donec rostra tenent siccum et sedere carinae<br />

omnes innocuae.<br />

When Tarchon has thus spoken, his comrades rise to<br />

their oars, and drive their foaming ships upon the Latin<br />

fields, till the beaks gain the dry land and every hull<br />

comes to rest unscathered.<br />

The historical infinitives indicate the existence of consurgere and inferre during the time<br />

between postquam effatus and donec tenent. During this time the states of affairs do not end;<br />

they are ongoing actions. This means that the infinitive inferre represents an unfinished state<br />

of affairs: in the time between the speech of Tarchon and the gaining of dry land the men are,<br />

indeed, in the process of driving the ships upon the Latin fields. The combination of inferre<br />

and a dative is telic, but durative (see §2.3.1) and one occurrence can fill the time frame<br />

provided in example (2).<br />

This is different in the case of consurgere. The combination consurgere tonsis refers<br />

to, as Harrison (1991) puts it, “the upward movement of body and oar in the pull”, and it<br />

seems very illogical to assume that the sailors moved upward so slowly that this upward<br />

movement took as long as the time in between the speech of Tarchon and the gaining of dry<br />

land. A more natural interpretation seems to be an iterative interpretation: consurgere<br />

represents the iterative movement of the socii pulling their oars up again and again as they<br />

row towards the Latin coast.<br />

In short, the infinitive indicates the existence of a state of affairs, and the meaning of<br />

the verb and its arguments do the rest.<br />

<strong>7.</strong>1.1 The Use of the <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Infinitive</strong> in the Aeneid<br />

Because a historical infinitive merely indicates the existence of a state of affairs, it needs a<br />

context to provide a time in which this state of affairs exists. This time may be explicitly<br />

demarcated by means of elements indicating the beginning and end, the boundaries of the<br />

state of affairs (see example (2)). Every instance of the historical infinitive in the Aeneid is<br />

provided by the context with a reference time with which the state of affairs is<br />

contemporaneous. If both beginning and end are indicated, the clause as a whole represents a<br />

bounded state of affairs (i.e. an event). The boundaries of the state of affairs are often not<br />

made explicit, however, as the overview below makes clear. In the latter cases, the infinitive<br />

is an unbounded state of affairs, i.e. a situation. <strong>Infinitive</strong>s that have an indication of their<br />

start, but none of the end are starting situations.<br />

Table 1: Boundaries of <strong>Historical</strong> <strong>Infinitive</strong>s in the Aeneid<br />

Indication of start Indication of end Type<br />

Ablative (temporal) (see example (4)) None Starting situation 5<br />

Adverb Conjunction (e.g. donec) Event 3<br />

Adverb None Starting situation 6<br />

Adverb End direct speech (verb of saying) Event 9<br />

Previous clause (incompatible) Conjunction Event 2<br />

Previous clause (incompatible) None Starting situation 1<br />

None, takes reference time of previous<br />

state of affairs<br />

Conjunction Situation 2<br />

None, takes reference time of previous Next clause (incompatible) Situation 2<br />

state of affairs<br />

None, takes reference time of previous<br />

state of affairs<br />

134<br />

None Situation 38<br />

68

HISTORICAL INFINTIVE<br />

It becomes clear from the table that most infinitives in the Aeneid are situations (42<br />

instances). In the rest of this chapter, I discuss the occurrence of the historical infinitive in the<br />

discourse modes. In this respect, the indication of the start of the historical infinitive is of<br />

importance: in the narrative mode, the start of the state of affairs is always indicated, whereas<br />

this is hardly ever the case in the directing mode and even never occurs in (transposed)<br />

description, as is shown in table 2.<br />

Table 2: Indications of the start of the state of affairs vs. discourse mode<br />

Indication of start Narrative mode Directing mode Description mode<br />

Explicit 21 5 0<br />

None 0 21 20<br />

Total 21 26 20<br />

The next sections aim to explain these correlations by showing that the infinitive is used to<br />

fulfill functions that the other tenses in the particular discourse mode cannot fulfill.<br />

<strong>7.</strong>2 Narrative Mode 207<br />

Base Time of narration Reference time<br />

Report Transposed Report<br />

Registering Directing<br />

Discourse<br />

Mode<br />

Narrative Transposed Narrative<br />

Description Transposed Description<br />

The narrative mode consists of states of affairs<br />

that take place on the time line of the story and<br />

may be characterized by a progression along this<br />

time line: reference time advances in the<br />

narrative mode (Smith 2003). Regular tenses in<br />

the narrative mode are the perfect and imperfect<br />

tense. This section aims to explain why the historical infinitive is in some cases used instead<br />

of the perfect or imperfect tense.<br />

Table (2) shows that the infinitive in the narrative mode always occurs with an explicit<br />

indication of the start of the state of affairs, as may be illustrated by example (3). Creusa<br />

seems to appear to Aeneas and then starts speaking, as the adverb tum indicates.<br />

Example (3), 2.771 - 775<br />

quaerenti et tectis urbis sine fine ruenti<br />

infelix simulacrum atque ipsius umbra Creusae<br />

uisa mihi ante oculos et nota maior imago.<br />

obstipui, steteruntque comae et uox faucibus haesit.<br />

tum sic adfari et curas his demere dictis:<br />

As I rushed in my quest madly and endlessly among<br />

the buildings of the city, there rose before my eyes<br />

the sad phantom and ghost of Creusa herself, a form<br />

larger than her wont. I was appalled, my hair stood<br />

up, and the voice choked in my throat. Then thus<br />

she spoke to me and with these words dispelled my<br />

cares: …<br />

The historical infinitives adfari and demere indicate the existence of the states of affairs in the<br />

reference time starting with tum. This is a description of what the historical infinitive does,<br />

but not an explanation why it is preferred to the imperfect or perfect tense in this example, for<br />

both the imperfect and perfect tense denote states of affairs taking place in reference time in<br />

the narrative mode, as also the infinitive may do. 208 Pinkster (1990:90) observes that the<br />

historical infinitive is comparable to the imperfect in the capacity of representing durative<br />

states of affairs, and to the perfect in its capacity to combine with words such as tum uero and<br />

hinc. In addition to this, I would like to suggest that the infinitive is used in a function which<br />

lies in between the function of the perfect and that of the imperfect, but which neither may<br />

fulfil (Viljamaa 1983:98): the infinitive is used for starting situations in the narrative mode.<br />

We could say that the narrator adapts the time frame of the historical infinitive according to<br />

207<br />

The infinitives in the narrative mode are found at: 2.98; 2.132; 2.169; 2.775; 2.98; 3.141; 3.153; 6.557; <strong>7.</strong>77;<br />

8.35; 8.215.<br />

208<br />

For the difference between the imperfect and the perfect tense, see §3.3.1 and §4.10.1.<br />

135

CHAPTER 7<br />

his needs: since none of the other tenses in the narrative mode may be used to denote the start<br />

of a state of affairs, the narrator uses a construction with the historical infinitive to do this in<br />

the narrative mode. 209<br />

The perfect tense and the historical infinitive differ with respect to the boundedness of<br />

the states of affairs they represent, since a perfect tense form presents a state of affairs as<br />

bounded and an infinitive may, depending on the time frame given, also denote an unbounded<br />

state of affairs. In the narrative mode, the infinitive represents states of affairs that start in<br />

reference time and continue, as may be observed in the example below. In contrast to the<br />

perfect tense forms reddidit and mugiit which represent bounded states of affairs on the time<br />

line of the story, the infinitives mugire, impleri and relinqui denote state of affairs that<br />

continue after the starting point which is indicated by means of the ablative discessu.<br />

Example (4), 8.213 – 218<br />

interea, cum iam stabulis saturata moueret<br />

Amphitryoniades armenta abitumque pararet,<br />

discessu mugire boues atque omne querelis<br />

impleri nemus et colles clamore relinqui.<br />

reddidit una boum uocem uastoque sub antro<br />

mugiit et Caci spem custodita fefellit.<br />

Meanwhile, when Amphitryon’s son was now moving<br />

the well-fed herds from their stalls and making ready<br />

to set out, the cattle lowed as they went; all the grove<br />

they fill with their plaint, and with clamour quit the<br />

hills. One heifer returned the cry, lowed from the high<br />

cave’s depths, and from her prison baffled the hopes of<br />

Cacus.<br />

The infinitives represent iterative states of affairs the end of which is left implicit. The<br />

semelfactive mugire evokes this iterative interpretation by its semantic value, whereas this<br />

interpretation is evoked in the case of impleri because of the subject omne nemus and the<br />

plural querelis, and in case of relinqui because the implied agens is a herd of cows. One<br />

person (or cow) leaves a certain place in one instance, but in the case of a herd of cows<br />

leaving takes some time. In short, the infinitives do not indicate the endpoint of these states of<br />

affairs, whereas perfect tense forms would have presented them as reaching an endpoint.<br />

The difference between the imperfect and the historical infinitive may not be clear at<br />

first sight, since both are used for situations taking place in reference time. The difference<br />

becomes more clear if we phrase the value of the imperfect tense more precisely: the state of<br />

affairs is contemporaneous with reference time, meaning that during reference time the state<br />

of affairs is ‘in full course’, and, as a result, must have started shortly before reference time.<br />

The historical infinitive in the narrative mode always occurs together with an explicit<br />

indication of the start of the state of affairs and, thus, starts in reference time. In contrast to<br />

this, the imperfect tense cannot be used to describe the start of a durative situation. 210 An<br />

adverb such as tum, for instance, does not describe the starting point of the state of affairs<br />

when it is used in combination with an imperfect tense form. Instead, it specifies the reference<br />

time, as it does in (5). The first lines of this example give a more general description of Fama,<br />

whereas tum indicates the return to the time of Dido’s and Aeneas’ adventure in the cave.<br />

Example (5), 4.184 – 190<br />

nocte uolat caeli medio terraeque per umbram<br />

stridens, nec dulci declinat lumina somno;<br />

luce sedet custos aut summi culmine tecti<br />

turribus aut altis, et magnas territat urbes,<br />

tam ficti prauique tenax quam nuntia ueri.<br />

haec tum multiplici populos sermone replebat<br />

gaudens, et pariter facta atque infecta canebat:<br />

By night, midway between heaven and earth, she flies<br />

through the gloom, screeching, and drops not her eyes<br />

in sweet sleep; by day she sits on guard on high<br />

rooftop or lofty turrets, and affrights great cities,<br />

clinging to the false and wrong, yet heralding truth.<br />

Now exulting in manifold gossip, she filled the nations<br />

and sang alike of fact and falsehood, …<br />

209<br />

The alternative construction of the verb coepere, incipere or ordiri with an infinitive occurs only eight times<br />

in the Aeneid.<br />

210<br />

Some commentaries on the Aeneid seem to distinguish an ingressive use of the imperfect tense, see §4.7n165<br />

an n166.<br />

136

HISTORICAL INFINTIVE<br />

The start of replere and canere is not indicated; instead, we enter the story world when<br />

Fama’s actions are already going on. Rather than providing an indication of the start of the<br />

state of affairs, tum marks the return to the actual story, thus indicating the time with which<br />

the states of affairs in the imperfect tense are contemporaneous.<br />

The use of the historical infinitive in the narrative mode seems to be the use from<br />

which some scholars have concluded that an ellips of coepi should be assumed whenever a<br />

historical infinitive occurs. 211 It is not the infinitive itself, however, that evokes an inchoative<br />

interpretation: it is the combination of an adverb or adverbial clause with the infinitive. In the<br />

narrative mode, the infinitive indicates the existence of the state of affairs, and the context<br />

indicates its starting point.<br />

The end of an infinitive in the narrative mode usually remains implicit, but it may be<br />

given, as is illustrated by example (6). Sinon tells that he promised to avenge the death of<br />

Palamedes, and that from that moment (hinc) Ulysses started to bother him in all kinds of<br />

ways (terrere, spargere, quaerere). The end point is here made explicit by means of the<br />

conjunctive donec (the state of affairs governed by donec is not expressed, for Sinon<br />

interrupts his story).<br />

Example (6), 2.94 – 102<br />

nec tacui demens et me, fors si qua tulisset,<br />

si patrios umquam remeassem uictor ad Argos,<br />

promisi ultorem et uerbis odia aspera moui.<br />

hinc mihi prima mali labes, hinc semper Vlixes<br />

criminibus terrere nouis, hinc spargere uoces<br />

in uulgum ambiguas et quaerere conscius arma.<br />

nec requieuit enim, donec Calchante ministro –<br />

sed quid ego haec autem nequiquam ingrata reuoluo,<br />

quidue moror?<br />

Nor in my madness was I silent, but, if any chance<br />

should offer, if I ever returned in triumph to my native<br />

Argos, I vowed myself his avenger and with my words<br />

awoke fierce hate. Hence for me the first taint of ill;<br />

hence would Ulysses ever terrify me with new<br />

charges; hence would he sow dark rumors in the crowd<br />

and with guilty fear seek weapons. Nor indeed did he<br />

rest until with Calchas as his tool – but why do I vainly<br />

unroll this unwelcome tale?<br />

The time frame given in example (6) by means of hinc and donec is, in case of the Aeneid,<br />

unusually long: it lasts at least a couple of days, if not weeks or months. We should not<br />

assume that Odysseus in this period never stopped terrifying, gossiping and picking fights and<br />

that the states of affairs were going on in one continuous flow. Instead, they describe how, in<br />

a rather large span of story time, Odysseus on and off frightened Sinon, gave him a bad name<br />

and tried to pick fights. This frightening, for instance, is an iterative state of affairs, but,<br />

moreover, it is an ‘interrupted’ state of affairs, since the individual events of frightening may<br />

be assumed to be separated in time.<br />

This technique of using the historical infinitive to describe regularly recurring events<br />

in a larger span of story time is not found often in the Aeneid, but is used, for instance, by<br />

Livy, and especially by Sallust, as Mark Woertman shows in his bachelor thesis (<strong>VU</strong><br />

University Amsterdam 2005). 212 He calls this technique, in Dutch, the discontinue infinitivus,<br />

211 Viljamaa (1983:93) also seems to hint at an inchoative interpretation of the infinitive.<br />

212 There is one example of the historical infinitive which seems to be transposed report, and this example may<br />

be explained from the ‘interrupted’ connotation it seems to have. When Camilla has been lethally wounded in<br />

book 11 (820-822), she speaks to her close friend Acca. The narrator provides us with the information that Acca<br />

was the sole sharer of her cares, and does so by means of the infinitive partiri: tum sic exspirans Accam ex<br />

aequalibus unam/ adloquitur, fida ante alias quae sola Camillae /quicum partiri curas, atque haec ita fatur…<br />

(transl.: Then, as her breath fails, she thus accosts Acca, one of her age-mates, true to Camilla beyond all the<br />

others, sole sharer of her cares, and thus she speaks:). In my opinion we should interpret this infinitive in an<br />

iterative way: every time Camilla had a problem, Acca stood by her side. This is also how I would interpret the<br />

only two instances of the ‘historical’ infinitive in direct speech: 4.420-423: miserae hoc tamen unum /exsequere,<br />

Anna, mihi; solam nam perfidus ille/ te colere, arcanos etiam tibi credere sensus;/sola uiri mollis aditus et<br />

tempora noras (transl.: Yet this one service, Anna, do for me – for you alone that traitor made his friend, to you<br />

137

CHAPTER 7<br />

which would translate as the interrupted infinitive, indicating that a state of affairs occurs<br />

every once in a while, during a given time span. Using a set of infinitives, the narrator may<br />

describe a time span, in which several actions took place, without giving too much detail<br />

about the chronological order or the specific amount of times these actions took place. It is a<br />

pretty sketchy and imprecise way of narrating. Sinon is especially fond of the historical<br />

infinitive, if we compare him to other narrators in the Aeneid, and this has to do with the<br />

impreciseness of the device: by keeping his story a bit vague the lies remain hidden. 213<br />

In the narrative mode, 21 infinitives occur and these starting situations all advance<br />

reference time. The total number of historical infinitives in the Aeneid is 68, and in the next<br />

section I will discuss the more frequent use of the historical infinitive in the directing mode.<br />

<strong>7.</strong>3 Directing Mode 214<br />

Base Time of narration Reference time<br />

Report Transposed Report<br />

Registering Directing<br />

Discourse<br />

Mode<br />

Narrative Transposed Narrative<br />

Description Transposed Description<br />

The directing mode is characterized by a<br />

simultaneous advancement of reference time,<br />

base and narrator. The states of affairs are<br />

presented as if they take place on a stage: the<br />

narrator is the director of the story. The<br />

interpretation of the historical infinitive in the<br />

directing mode is the same as in the narrative mode: it denotes the existence of a state of<br />

affairs taking place in a given reference time.<br />

An important difference with the infinitive in the narrative mode is found in the tense<br />

forms with which the infinitive ‘competes’. In the narrative mode, the perfect denotes events,<br />

the imperfect situations and the infinitive denotes what the other two tenses cannot describe:<br />

starting situations. In the directing mode, events, situations and starting situations are<br />

described by means of present tense forms (see chapter 2). In the directing mode, the<br />

motivation for the use of the infinitive is, therefore, not that the present tense cannot indicate a<br />

specific type of state affairs. 215 The infinitive is used in these cases for other reasons, as may<br />

be illustrated by example (7), in which the infinitives indicate starting situations. The ships of<br />

the Trojans are burning, and Aeneas prays to Jupiter to send rain to stop the fire. The temporal<br />

adverb tum indicates a shift in reference time and at the same time marks the starting point of<br />

the states of affairs in the historical infinitives abscindere, uocare and tendere.<br />

Example (7), 5.680 – 686<br />

Sed non idcirco flamma atque incendia uiris<br />

indomitas posuere; udo sub robore uiuit<br />

stuppa uomens tardum fumum, lentusque carinas<br />

est uapor et toto descendit corpore pestis,<br />

nec uires heroum infusaque flumina prosunt.<br />

tum pius Aeneas umeris abscindere uestem<br />

auxilioque uocare deos et tendere palmas:<br />

But not for that did the burning flames lay aside their<br />

unquelled fury; under the wet oak the tow is alive,<br />

slowly belching smoke; the smouldering heat devours<br />

the keels, a plague sinking through the whole frame,<br />

nor can the herous’ strength, nor the floods they pour<br />

avail. Then loyal Aeneas rent the garment from his<br />

shoulders, and called the gods to his aid, lifting up his<br />

hands: …<br />

he confided even his secret thoughts, you alone will know the hour for easy access to him – go, sister, and<br />

humbly address our haughty foe.)<br />

213<br />

Total number of tense forms<br />

(+infinitive) in narrative mode<br />

<strong>Historical</strong> infinitive<br />

Main narrator 299 7<br />

Aeneas 71 5<br />

Sinon 27 6<br />

Other 83 3<br />

214 The infinitives in the directing mode are given in table 3.<br />

215 These are the infinitives in 10.299ff and in 5.685ff.<br />

138

HISTORICAL INFINTIVE<br />

In this particular environment, present tense forms (abscindit uestem, uocat deos and tendit<br />

palmas) would have been a clear-cut chronological representation of three following events,<br />

whereas these historical infinitives present Aeneas’ activities as situations that continue<br />

during his speech and that take place more or less simultaneously. Aeneas is ripping his<br />

clothes, calling to the gods and stretching his palms several times, and in an unspecified order.<br />

This example shows that the infinitive may be used in the directing mode to avoid the idea<br />

progression of reference time.<br />

However, such a clear contrast between the present tense and infinitives is not found<br />

in all cases of the infinitive in the directing mode. In several cases, the infinitive as an<br />

alternative for a present tense form seems to yield only a slightly different shade of meaning. I<br />

propose that the infinitive is preferred to the present tense in environments in which a<br />

relatively large degree of ‘dynamism’, ‘vigor’ or ‘vividness’ seems appropriate. This is, of<br />

course, an observation found more often (eg. Schlicher 1914a:287). However, I will provide<br />

some linguistic support. This support is based on the following observations:<br />

- the infinitive often denotes an iterative or distributive state of affairs<br />

- it may represent accomplishment predicate frames as unsuccessful states of<br />

affairs<br />

- it often denotes a state of affairs that is simultaneous to the previous state of<br />

affairs (usually a present tense form)<br />

- all infinitives in the directing mode take place in another part of the stage than<br />

the previous state of affairs<br />

The following examples will show how the semantic value of the infinitive (viz. to indicate<br />

the existence of a state of affairs in a given reference time) makes a certain scene more<br />

vigorous. 216<br />

An iterative interpretation of an infinitive, of course, makes a scene more vigorous in<br />

that it represents a repetitive action, as is the case in example (8), in which the Trojans are<br />

defending their camp against Italian soldiers by throwing all kinds of weapons at them (omne<br />

genus telorum effundere). More and more missiles are falling down and, as is expressed by<br />

means of detrudere, the Trojans are thrusting down enemies who keep climbing up again and<br />

again.<br />

Example (8), 9. 507 – 511<br />

quaerunt pars aditum et scalis ascendere muros,<br />

qua rara est acies interlucetque corona<br />

non tam spissa uiris. telorum effundere contra<br />

omne genus Teucri ac duris detrudere contis,<br />

adsueti longo muros defendere bello.<br />

Some seek an entrance, and try to scale the walls<br />

with ladders, where the line is thin and light gleams<br />

through a less dense ring of men. In return, the<br />

Teucrians are hurling missiles of every sort, and are<br />

thrusting the foe down with strong poles, trained by<br />

long warfare to defend their walls.<br />

These infinitives denote the existence of effundere and detrudere in the reference time of<br />

quaerunt and, since throwing weapons once usually takes only a short period of time and the<br />

endpoint of effundere is not explicitly indicated, we assume a repetition of effundere and<br />

detrudere. This iterative interpretation is also evoked because of the object omne genus, of<br />

course. The infinitives make this passage more vigorous because they suggest that the<br />

216 Present tense forms may , of course, also represent iterative states of affairs (e.g. frangitur in 1.161), present<br />

an accomplishment as a state of affairs which is unfinished (e.g. implentur in 5.697) or describe situations that<br />

take place in another part of the stage (e.g. locant in 1.213).<br />

139

CHAPTER 7<br />

narrator’s eye is suddenly caught by something that also takes place in this reference time, as<br />

he switches from one location of the stage (the walls) to another (the top of the walls).<br />

Another example in which both an iterative interpretation of the infinitives and a<br />

switch between parts of the mental stage contribute to the vigor of the scene is also found in<br />

book 9, when Turnus is locked inside the Trojan camp and tries to escape. The infinitives<br />

excedere, petere, incumbere and glomerare convey iterative events: Turnus takes one step and<br />

the Trojans follow him, and then Turnus takes another step and the Trojans follow again.<br />

Example (9), Aeneid 9.788 – 798<br />

talibus accensi firmantur et agmine denso<br />

consistunt. Turnus paulatim excedere pugna<br />

et fluuium petere ac partem quae cingitur unda.<br />

acrius hoc Teucri clamore incumbere magno<br />

et glomerare manum.<br />

Kindled by such words, they take heart and halt in<br />

dense array. Step by step Turnus is withdrawing from<br />

the fight, making for the river and the place encircled<br />

by the stream. All the more fearlessly the Teucrians are<br />

pressing on him with loud shouts and massing their<br />

ranks.<br />

Moreover, the infinitives excedere pugna and fluuium petere represent unbounded states of<br />

affairs and do not reach their endpoint in reference time (cf.Viljamaa 1983:34). This would<br />

not have been the interpretation of present tense forms: present tense forms would have<br />

implied that Turnus indeed reached the river. That is, present tense forms would have evoked<br />

an interpretation of success, as is the case in (10), in which Aeneas narrates how he and some<br />

of his fellow Trojans pretended to be Greeks during the sack of Troy. 217<br />

Example (10), Aeneid, 2.396 – 401<br />

uadimus immixti Danais haud numine nostro<br />

multaque per caecam congressi proelia noctem<br />

conserimus, multos Danaum demittimus Orco.<br />

diffugiunt alii ad nauis et litora cursu<br />

fida petunt; pars ingentem formidine turpi<br />

scandunt rursus equum et nota conduntur in aluo.<br />

We move on, mingling with the Greeks, under gods<br />

not our own, and in the blind night we clash in many<br />

a close fight, and many a Greek send down to Orcus.<br />

Some scatter to the ships and make with speed for<br />

safe shores; some in base terror again climb the huge<br />

horse and hide in the familiar womb.<br />

In contrast to fluuium petere in the previous example, diffugiunt alii and litora petunt are<br />

successful actions: we may assume that the Greeks indeed reach their ships. The contrast<br />

between example (9) and (10) shows that the infinitive enhances the vigor of a scene more<br />

than a present tense form would have done, since it evokes an unfinished and iterative effect<br />

and may be used to switch from one side of the ‘stage’ (Turnus) to another (Trojans).<br />

The infinitive denotes that the state of affairs exists in reference time and, in case of<br />

accomplishment and achievement verbs, states nothing about the success or end of the state of<br />

affairs. Therefore, the infinitive may be used also to postpone the interpretation that a state of<br />

affairs is successful. I think this is how we should interpret the infinitives in example (11).<br />

This passage is found in book 3, where Aeneas tells how the Trojans sail past the island of the<br />

Cyclopes and pick up the Greek Achaemenides. The narrator (Aeneas) first describes how<br />

Polyphemus enters the sea and approaches Aeneas’ ship; then, the narrator switches to what<br />

the Trojans are doing at the same moment (nos procul inde): we catch the Trojans as they are<br />

‘speeding their flight’ or, more specifically, at the exact moment of cutting the rope.<br />

Example (11), 3. 662 – 668<br />

postquam altos tetigit fluctus et ad aequora uenit,<br />

luminis effossi fluidum lauit inde cruorem<br />

dentibus infrendens gemitu, graditurque per aequor<br />

As soon as he touched the deep waves and reached<br />

the sea, he washed therein the oozing blood from his<br />

eye’s socket, gnashing his teeth and groaning, then<br />

217 Of course, present tense forms of accomplishment verbs may get an unbounded reading as well, as I showed<br />

in §2.3.1, but in the particular case of example (9) and several other instances of the infinitive a present tense<br />

form would not have evoked such an unbounded reading.<br />

140

iam medium, necdum fluctus latera ardua tinxit.<br />

nos procul inde fugam trepidi celerare recepto<br />

supplice sic merito tacitique incidere funem,<br />

uertimus et proni certantibus aequora remis.<br />

HISTORICAL INFINTIVE<br />

strides through the open sea; nor has the wave yet<br />

wetted his towering sides. Desperately we are<br />

speeding our flight far from there, taking on board a<br />

suppliant so deserving, and silently we are cutting<br />

the cable; then, bending forward, sweep the seas with<br />

eager oars.<br />

Although incidere funem, cutting a rope, would – in real life – be a near momentaneous event,<br />

I think that the infinitive is used to present it as it is going on in reference time, simultaneous<br />

to Polyphemus approaching the ship. The reader only knows at uertimus that the incidere<br />

must have been successful, whereas a present tense form would have given this information<br />

immediately. In this way, the infinitives contribute to the suspense of this passage, which is<br />

also evoked, of course, by the semantic content of the words trepidi and celerare.<br />

The above examples have shown that the infinitive usually increases the vigor of a<br />

scene in more than one way. As I said above, all infinitives in the directing mode suggest that<br />

the narrator changes his perspective and tells what is going on in another part of the stage.<br />

The state of affairs may be iterative, simultaneous to the previous state of affairs, unsuccessful<br />

or a combination of these things. Table 3 provides an overview of the infinitives in the<br />

directing mode and the ways in which they make a certain scene more vigorous.<br />

Table 3: <strong>Infinitive</strong>s in the directing mode<br />

Start of cluster <strong>Infinitive</strong> Iterative Unsuccessful in<br />

reference time<br />

Simultaneous<br />

3.666 celerare X<br />

incidere X X<br />

5.655 spectare X<br />

5.685 abscindere X<br />

vocare X<br />

tendere X<br />

6.199 prodire X X<br />

6.256 mugire X X<br />

8.493<br />

9.377<br />

9.509<br />

confugere X X<br />

defendier X X<br />

tendere X X<br />

celerare X<br />

fidere X X<br />

effundere X X<br />

detrudere X X<br />

9.789 excedere X X<br />

petere X X<br />

incumbere X<br />

glomerare X X<br />

10.267 videri X<br />

10.288 servare X X<br />

credere X X<br />

10.299 consurgere X X X<br />

inferre X X X<br />

12.216 videri X<br />

misceri X X<br />

As I said above, all infinitives in the directing mode suggest that the narrator changes his<br />

viewpoint and tells what is going on in another part of the mental stage.<br />

Above, the infinitive was constrasted with the present tense. I conclude this section by<br />

contrasting the infinitive with the imperfect in the directing mode. Both tenses are used in this<br />

mode to indicate what was/is happening in another part of the stage as the narrator was telling<br />

141

CHAPTER 7<br />

something else. In case of the infinitive, the narrator focuses on what is happening in<br />

reference time, not caring about what was happening before this reference time, whereas he,<br />

in case of the imperfect, focuses on what was happening before reference time, as flebant and<br />

aspectabant in example (12) illustrate. Iris (illa), sent to earth by Juno, is looking for a<br />

possibility to delay Aeneas’ departure to the Italian mainland, when her eye catches the<br />

Trojan women crying. The imperfect tense forms flebant and aspectabant focus on this past<br />

of story now: the narrator provides us with the information that the women were crying<br />

already before this reference time (see §4.6.1).<br />

Example (12), 5.609- 617<br />

illa uiam celerans per mille coloribus arcum<br />

nulli uisa cito decurrit tramite uirgo.<br />

conspicit ingentem concursum et litora lustrat<br />

desertosque uidet portus classemque relictam.<br />

at procul in sola secretae Troades acta<br />

amissum Anchisen flebant, cunctaeque profundum<br />

pontum aspectabant flentes. heu tot uada fessis<br />

et tantum superesse maris, uox omnibus una;<br />

urbem orant, taedet pelagi perferre laborem.<br />

Iris, speeding her way along her thousand-hued<br />

rainbow, runs swiftly down her path, a maiden seen<br />

of none. She views the vast throng, scans the shore,<br />

and sees the harbour forsaken and the fleet<br />

abandoned. But far apart on the lonely shore the<br />

Trojan women wept for Anchises’ loss, and all, as<br />

they wept, gazed on the fathomless flood. “Ah, for<br />

weary folk what waves remain, what wastes of sea!”<br />

Such is the one cry of all. It is a city they crave; of<br />

the sea’s hardships they have had enough.<br />

<strong>Historical</strong> infinitives, by contrast, would have meant here that the crying of the women filled<br />

the time frame of Iris watching them, whereas they had been crying long before that (cf.<br />

5.655).<br />

There is one instance of the infinitive in the directing mode which seems<br />

interchangeable with an imperfect tense form. This is in Aeneid 12.216, where the historical<br />

infinitive uideri co-occurs with the adverb iamdudum indicating that the Rutulians considered<br />

the fight between Aeneas and Turnus unfair long before reference time.<br />

Example (13), 12.216 - 218<br />

At uero Rutulis impar ea pugna uideri<br />

iamdudum et uario misceri pectora motu,<br />

tum magis ut propius cernunt non uiribus aequos.<br />

But to the Rutulians the battle had long seemed<br />

unequal, and their hearts, swayed to and from, had<br />

long been in turmoil; all the more now when they<br />

beheld the combatants at closer view not matched in<br />

strenghth. (in ill-matched strength)<br />

However, imperfect tense forms would not yield exactly the same effect. Imperfect tense<br />

forms would have focused on the fact that the Rutulians had been dissatisfied for a long time<br />

now. The infinitive in combination with iamdudum does, of course, give this information, but<br />

it focuses on the fact that they are at this time (tum … ut propius cernunt non uiribus aequos)<br />

even more dissatisfied.<br />

In summary, an infinitive in the directing mode suggests that the narrator’s eye is<br />

suddenly caught by some state of affairs taking place elsewhere in the scene at the already<br />

given moment (cf. Rosén 1995:560; cf. also Eden on 8.493). If reference time is, so to speak,<br />

too long for one occurrence of the state of affairs, the infinitive suggests a repetition.<br />

Therefore, the historical infinitive is an appropriate verb form in contexts which intuitively<br />

seem rather ‘busy’ or ‘chaotic’ because many things happen simultaneously (Schlicher<br />

1914a:287). The infinitives may be used in battle scenes especially to suggest a very high<br />

density of events and situations. Many things happen in the story world at once and the<br />

narrator tells them as they ‘catch his eye’ and leaves it to his readers to picture all the events<br />

as happening simultaneously. The narrator, as it were, pretends not to have the time, or the<br />

overview, to give a detailed chronological order.<br />

142

<strong>7.</strong>4 Transposed Description Mode<br />

Base Time of narration Reference time<br />

Report Transposed Report<br />

Registering Directing<br />

Discourse<br />

Mode<br />

Narrative Transposed Narrative<br />

Description Transposed Description<br />

HISTORICAL INFINTIVE<br />

The transposed description mode is characterized<br />

by sequences of states of affairs that do not<br />

advance reference time, but, instead, evoke the<br />

idea of spatial progression over the surface of an<br />

object or through the scenery. In the transposed<br />

description mode, the base is positioned in<br />

reference time. It is characterized by unbounded states of affairs expressed by present tense<br />

forms. The use of the infinitive in transposed description is quite similar to that in the<br />

directing mode: the infinitive indicates a state of affairs that is contemporaneous with a given<br />

reference time and that is more vigorous in comparison to the present tense. It is, therefore,<br />

not surprising that the infinitives all occur in transposed dynamic descriptions (§2.7).<br />

<strong>Infinitive</strong>s in the description mode indicate a switch from one part of the stage to another.<br />

This may be illustrated by means of an example taken from book 6 in which the narrator<br />

changes his view from the Trojans who are happy to welcome Aeneas to the Greeks who fear<br />

him. The change of view is marked by means of at (see (13) above).<br />

Example (14), 6.486 – 493<br />

circumstant animae dextra laeuaque frequentes,<br />

nec uidisse semel satis est; iuuat usque morari<br />

et conferre gradum et ueniendi discere causas.<br />

at Danaum proceres Agamemnoniaeque phalanges<br />

ut uidere uirum fulgentiaque arma per umbras,<br />

ingenti trepidare metu; pars uertere terga,<br />

ceu quondam petiere rates, pars tollere uocem<br />

exiguam: inceptus clamor frustratur hiantis.<br />

Round about, on right and left, stand the souls in<br />

throngs. To have seen him once is not enough; they<br />

delight to linger, to pace beside him, and to learn the<br />

causes of his coming. But the Danaan princes and<br />

Agamemnon’s battalions, soon as they saw the man<br />

and his arms flashing amid the gloom, trembled with<br />

mighty fear; some turn to flee, as of old they sought<br />

the ships; some raise a shout – faintly; the cry essayed<br />

mocks their gaping mouths.<br />

The semantic content of the verb trepidare here contributes to the vigor of this description, as<br />

well as the repetition of pars. Despite the excitement and movement of the Greeks, reference<br />

time does not advance in these lines and we should, therefore, analyze this excerpt as<br />

description. Present tense forms would probably evoke a similar interpretation in this passage<br />

(cf. 6.642), which leads me to conclude that the infinitives are used merely for presentational<br />

reasons: they make this description more vigorous. The historical infinitive always does this<br />

in the description mode. 218<br />

The same explanation should be given to the two infinitives occurring in ekphrasis.<br />

The verbs ruere and spumare may indeed occur in the present tense (e.g. 12.526 and 3.534),<br />

but the infinitives of these verbs in my opinion create the very vivid effect that the waves<br />

seem to spatter from the shields.<br />

Example (15), 8.685 – 690<br />

hinc ope barbarica uariisque Antonius armis,<br />

uictor ab Aurorae populis et litore rubro,<br />

Aegyptum uirisque Orientis et ultima secum<br />

Bactra uehit, sequiturque (nefas) Aegyptia coniunx.<br />

una omnes ruere ac totum spumare reductis<br />

conuulsum remis rostrisque tridentibus aequor.<br />

Alta petunt. …<br />

On the other side comes Antony with barbaric might<br />

and motley arms, victorious over the nations of the<br />

dawn and the ruddy sea, bringing in his train Egypt<br />

and the strength of the East and farthest Bactra; and<br />

there follows him (oh the shame of it!) his Egyptian<br />

wife. All rush on at once, and the whole sea foams,<br />

torn up by the sweeping oars and triple-pointed beakts.<br />

To the deep they race …<br />

218 The infinitive is found in the transposed description mode at 1.423; 2.685; 6.491; <strong>7.</strong>015; 9.538; 11.142 and<br />

11.883. The infinitive trepidare occurs in three descriptions (2.685; 6.491; 9.538), whereas there are only 8<br />

instances of this verb in the Aeneid (in narrator text).<br />

143

CHAPTER 7<br />

These infinitives are clearly part of the description mode in that they do not advance reference<br />

time but describe what is to be seen on another part of the shield. Therefore, I do not agree<br />

with Conington (1963) when he says: “in the following passage Virgil seems almost to forget<br />

that he is not telling a story but describing a picture.” (cf. also Fordyce 1977 ad locum). What<br />

is remarkable, however, is the vivid nature of this picture: waves depicted on a shield do not<br />

move or scatter drops of water. If Vergil has “forgotten” anything, it is the fact that he is<br />

describing a static object.<br />

<strong>7.</strong>5 Conclusion<br />

The narrator of the Aeneid uses the historical infinitive in various ways, all of which have to<br />

do with its basic function: the infinitive denotes the existence of a state of affairs in a given<br />

time. A state of affairs expressed by an infinitive has no beginning and end of itself, but may<br />

be presented as a bounded state of affairs with the context providing a starting or ending<br />

point.<br />

In earlier studies, the historical infinitive is described as a verb form that has features<br />

of both the imperfect and the perfect, or as a verb form for which an ellips of coepi must be<br />

assumed. In my opinion, these suggestions were made on the basis of infinitives in the<br />

narrative mode. It is in this mode that the infinitive, in combination with an adverb, denotes<br />

the start of states of affairs. This is a function that neither the imperfect nor the perfect may<br />

fulfill, which means that, in the narrative mode, the infinitive indeed lies in between the<br />

imperfect and the perfect tense.<br />

In the directing and transposed description mode the state of affairs expressed by<br />

means of the infinitive usually takes the reference time of the previous state of affairs. In these<br />

modes, the infinitive is most often used to denote unsuccessful, and/or iterative states of<br />

affairs, which do not advance narrative time. The narrator uses it in exciting and chaotic<br />

passages to look, as it were, from one part of the stage to another. Therefore, an infinitive<br />

usually adds extra vigor to a scene.<br />

An overview of all interpretations of the infinitive is given below:<br />

Intepretations of the historical infinitive<br />

Base in Time of Narration (TofN) Base in Reference Time (RT)<br />

Interpretation of historical infinitive Interpretation of historical infinitive<br />

Report mode Dynamic situation in RT (explicit)<br />

(§<strong>7.</strong>2n212)<br />

Registering mode<br />

Contemporaneous with RT (explicit)<br />

– Directing mode<br />

(§<strong>7.</strong>3)<br />

Narrative mode Start in RT (explicit) (§<strong>7.</strong>2) 21<br />

Description mode Dynamic situation in RT (explicit)<br />

(§<strong>7.</strong>4)<br />

144<br />

1<br />

26<br />

20

HISTORICAL INFINTIVE<br />

In sum, the discourse modes provide a framework by means of which long recognized uses of<br />

the infinitives may be described in a more systematic way and based on explicit linguistic<br />

argumentation. The infinitive is the last of the verb forms discussed in this study, and the<br />

framework of discourse modes is completed as far as the narrative tenses are concerned. The<br />

interpretation of the tenses within the discourse modes are summarized below.<br />

Tenses in Discourse Modes<br />

BASE IN TIME OF NARRATION (TOFN) BASE IN REFERENCE TIME (RT)<br />

REPORT MODE TRANSPOSED REPORT<br />

Praesens §2.2: Contemporaneous with TofN 490 §2.6: Contemporaneous with RT 40<br />

Perfectum §3.3: Anterior to TofN 266 §3.5: Anterior to RT 32<br />

Imperfectum §4.4: Contemporaneous with 25 §4.5: Contemporaneous with explicit 19<br />

explicit moment in past of TofN moment in past of RT<br />

Plusquam- §5.2: Anterior to explicit moment in 5 §5.4n180: Anterior to explicit<br />

3<br />

perfectum past of TofN<br />

moment in past of RT<br />

Futurum §6.1: Posterior to TofN 16 §6.3: Posterior to RT 1<br />

Futurum<br />

§6.3: Anterior to moment in past of 2<br />

Exactum<br />

RT<br />

Infinitivus §<strong>7.</strong>2n212: Dynamic situation in RT<br />

(explicit)<br />

1<br />

Pr./Pft. §3.3n95 3<br />

REGISTERING DIRECTING<br />

Praesens §2.2: Contemporaneous with TofN 9 §2.4: Contemporaneous with RT 2673<br />

alone<br />

alone<br />

Perfectum §3.4: (Immediately) anterior to RT 553<br />

Imperfectum §4.6: Contemporaneous with moment<br />

in recent past of RT<br />

179<br />

Plusquam-<br />

§5.5: Anterior to moment in recent 63<br />

perfectum<br />

past of RT<br />

Infinitivus §<strong>7.</strong>3: Contemporaneous with RT<br />

(explicit)<br />

26<br />

Pr./Pft. §3.4.2n112 85<br />

NARRATIVE (TRANSPOSED NARRATIVE (§1.2.2))<br />

(Praesens) §2.0n33: dum-clauses 13<br />

Perfectum §3.2: Event in RT 462<br />

Imperfectum §4.2: Situation in RT 183<br />

Plusquamperfectum<br />

§5.3: Anterior to RT 104<br />

Infinitivus §<strong>7.</strong>2: Start in RT (explicit) 21<br />

Ait/inquit §3.2n91 12<br />

DESCRIPTION TRANSPOSED DESCRIPTION<br />

Praesens §2.7: Situation in RT 336<br />

Perfectum §3.6: Anterior to RT, resulting<br />

situation in RT<br />

25<br />

Imperfectum §4.3: Situation in RT 69 §4.7: Contemporaneous with moment<br />

in past of RT (continuing in RT)<br />

52<br />

Plusquam- §5.6: Anterior to RT, resulting 1 §5.6: Anterior to moment before RT, 4<br />

perfectum situation in RT<br />

resulting situation in past of RT<br />

Infinitivus §<strong>7.</strong>4: Dynamic situation in RT<br />

(explicit)<br />

20<br />

Now that the use of the individual tenses within each discourse mode has been explained, we<br />

can turn to the question how these discourse modes themselves function in the Aeneid as a<br />

whole. This is the subject of the next chapter.<br />

145

146