Disclosing Harmful Medical Errors to Patients - Harvard University

Disclosing Harmful Medical Errors to Patients - Harvard University

Disclosing Harmful Medical Errors to Patients - Harvard University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

T h e n e w e ng l a nd j o u r na l o f m e dic i n ereview articlecurrent concepts<strong>Disclosing</strong> <strong>Harmful</strong> <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Errors</strong><strong>to</strong> <strong>Patients</strong>Thomas H. Gallagher, M.D., David Studdert, LL.B., Sc.D., M.P.H.,and Wendy Levinson, M.D.Studies from more than six countries 1-7 report a high prevalenceof harmful medical errors. Most providers and patients realize that healthcare services are potentially hazardous and that errors sometimes occur despitethe best efforts of people and institutions. 8 <strong>Patients</strong> expect <strong>to</strong> be informedpromptly when they are injured by care, especially care that has gone wrong. 9 However,a divide between these expectations and actual clinical practice is increasinglyevident. 8-12Regula<strong>to</strong>rs, hospitals, accreditation organizations, and legisla<strong>to</strong>rs in the UnitedStates and other countries are moving <strong>to</strong> bridge the gap by developing standards,programs, and laws that encourage transparent communication with patients afterharmful errors have been made. In the United States, the National Quality Forum(NQF), an organization that develops standards for health care delivery through aprocess of developing a consensus among stakeholders and experts, recently addedstandards for disclosure of unanticipated outcomes <strong>to</strong> its list of safe practices. 13Several institutions report that the implementation of aggressive disclosure policieshas reduced their exposure <strong>to</strong> malpractice litigation. 14,15 A few states have mandatedthe disclosure of certain events <strong>to</strong> patients, and many states have adopted lawsthat protect apologies for unanticipated outcomes from being used in litigation asevidence of fault on the part of the provider. 16,17 Australia 18 and the United Kingdom19 have launched ambitious disclosure programs.Although the push for transparency originated outside the medical profession,there appears <strong>to</strong> be increasing receptivity <strong>to</strong> the concept within the profession. 20His<strong>to</strong>rically, physicians have been conflicted about disclosure. They have wanted <strong>to</strong>be open with patients but have been fearful of litigation, embarrassed, or unsureof effective disclosure strategies. A professional ethos of discretion or even coverupafter harmful errors predominated, 21 but there is emerging evidence of greateropenness <strong>to</strong> disclosure. In a recent survey in Canada and the United States, physiciansgenerally endorsed the importance of disclosing harmful errors <strong>to</strong> patients. 22External pressures for disclosure, coupled with some thawing of reluctance withinthe medical profession, have created an environment that is ripe for change.From the Department of Medicine andthe Department of <strong>Medical</strong> His<strong>to</strong>ry andEthics, <strong>University</strong> of Washing<strong>to</strong>n, Seattle(T.H.G.); the Melbourne Law School andthe School of Population Health, <strong>University</strong>of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia(D.S.); and the <strong>University</strong> of Toron<strong>to</strong>, Toron<strong>to</strong>(W.L.). Address reprint requests <strong>to</strong>Dr. Gallagher at the Department of Medicine,<strong>University</strong> of Washing<strong>to</strong>n, P.O. Box354981, Seattle, WA 98105-4608, or atthomasg@u.washing<strong>to</strong>n.edu.N Engl J Med 2007;356:2713-9.Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts <strong>Medical</strong> Society.Discl osur e S ta nda r dsUntil recently, virtually no guidance was available <strong>to</strong> health care professionals regardinghow or when <strong>to</strong> disclose errors; professional societies merely identified disclosureas an ethical obligation. 23-25 In 2001, the Joint Commission on Accreditationof Healthcare Organizations, now called the Joint Commission, issued the firstnationwide disclosure standard. 26 This standard requires that patients be informedn engl j med 356;26 www.nejm.org june 28, 2007 2713Downloaded from www.nejm.org at HARVARD UNIVERSITY on June 29, 2007 .Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts <strong>Medical</strong> Society. All rights reserved.

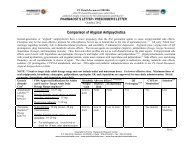

T h e n e w e ng l a nd j o u r na l o f m e dic i n eabout all outcomes of care, including “unanticipatedoutcomes.” It was a modest start. The standarddid not specify the content of disclosure, nordid it mandate that patients be <strong>to</strong>ld when unanticipatedoutcomes were due <strong>to</strong> error, partly ou<strong>to</strong>f concern that the standard not force admissionsof liability. 27 Nonetheless, the Joint Commission’smove was groundbreaking; it heralded a shiftfrom mere endorsement of the importance of disclosure<strong>to</strong> a requirement with teeth because it waslinked <strong>to</strong> the accreditation status of hospitals.Health care organizations have responded <strong>to</strong>the Joint Commission’s standard in varying ways.A 2002 survey of institutional risk managersshowed that 36% of institutions had establisheddisclosure policies 28 ; by 2005, this fraction hadapparently increased <strong>to</strong> 69%. 29 These policiesrange from simple restatements of the Joint Commission’sstandard <strong>to</strong> quite detailed disclosureprocedures. 30,31 There is little systematic evidenceavailable regarding the impact of these new policieson the practice of disclosure.Interest in disclosure is also growing outsidethe United States. In 2003, Australia launched its“Open Disclosure Standard,” which is currentlybeing tested in pilot programs across the country.18 A similar disclosure initiative, “Being Open,”was promulgated in the United Kingdom; it wasaccompanied by an ambitious educational campaign.19 Both programs strongly encourage transparentcommunication with patients after unanticipatedoutcomes, and they supply some impressive<strong>to</strong>ols for helping clinicians achieve this goal.However, neither program addresses how disclosureshould proceed in circumstances in whichthe unanticipated outcome was caused by error,other than generally stressing the importance ofnot admitting liability. Compliance with thesestandards is not currently manda<strong>to</strong>ry in eithercountry, and <strong>to</strong> our knowledge, outcomes datahave not yet been published.Last year, disclosure efforts in the UnitedStates <strong>to</strong>ok important steps forward. In March2006, the Full Disclosure Working Group of the<strong>Harvard</strong> Hospitals released a consensus statementemphasizing the importance of disclosing,taking responsibility, apologizing, and discussingthe prevention of recurrences. 30 In November2006, the NQF endorsed a new safe-practiceguideline on the disclosure of serious unanticipatedoutcomes <strong>to</strong> patients. 13 NQF safe practicesare evidence-based practices that, according <strong>to</strong>expert opinion and consensus among major quality-of-careorganizations such as the Joint Commission,the Institute for Healthcare Improvement,the Agency for Healthcare Research andQuality, and the Centers for Medicare and MedicaidServices, represent essential dimensions ofhigh-quality health care.The new safe practice is poised <strong>to</strong> advancedisclosure in important ways (Table 1). First, itframes the disclosure of unanticipated outcomes<strong>to</strong> patients as a core component of high-qualityhealth care. Traditionally, communication withpatients about unanticipated outcomes has beenhandled by risk managers who sought <strong>to</strong> minimizemalpractice claims and often operated independentlyof the institution’s quality and safetyleaders. By presenting disclosure as a patientsafetychallenge rather than a risk-managementproblem, the safe practice emphasizes that effectivedisclosure is a component of broad systemimprovement. It also encourages hospitals <strong>to</strong> integratetheir risk-management, patient-safety, andquality programs.Second, the safe practice recognizes that disclosuresare uniquely challenging conversationsand calls for appropriate staff preparation. Fewclinicians have had training in disclosure, andeven for those who have, disclosure conversationsoccur infrequently enough <strong>to</strong> make support necessaryat the critical moment. The safe practicedescribes a support system that provides trainingfor health care workers and coaching justbefore a disclosure. Third, the safe practice outlinesthe basic content of the disclosure discussion,which includes an expression of regret forunanticipated outcomes and an apology if errorplayed a causal role. Fourth, it encourages the applicationof performance-improvement <strong>to</strong>ols <strong>to</strong>the disclosure process, beginning with the trackingof disclosure outcomes.The potency of the safe-practice guidelines,like that of the Joint Commission’s standard,stems from the presence of an underlying enforcementmechanism. The 29 large health carepurchasing coalitions in the Leapfrog Group usethe NQF safe practices as standards in their payfor-performanceprograms. 32 In addition, morethan 1300 hospitals representing more than halfof the nation’s hospital beds currently submit informationregarding their compliance with thesesafe practices <strong>to</strong> the Leapfrog Group, which thenpublishes the information on the Internet. Thus,2714n engl j med 356;26 www.nejm.org june 28, 2007Downloaded from www.nejm.org at HARVARD UNIVERSITY on June 29, 2007 .Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts <strong>Medical</strong> Society. All rights reserved.

current conceptsperformance scores for disclosure will soon bepublicized alongside hospital-specific scores related<strong>to</strong> each of the other safe practices. 33 Thiscombination of direct financial incentives andvisibility <strong>to</strong> consumers has the potential <strong>to</strong> catalyzethe development of relatively sophisticateddisclosure programs.Skeptics may question whether the NQF’s endorsemen<strong>to</strong>f disclosure will promote substantivechange. Compliance with the safe practices isvoluntary, and the submitted data are not externallyvalidated. Moreover, many health care organizationsdo not participate in NQF or Leapfrogprograms. Nonetheless, the NQF standard representsa sensible step forward, given the limiteddata on effective disclosure strategies. In particular,its link <strong>to</strong> the pay-for-performance movementmay prove <strong>to</strong> be strategically important.Legal De v el opmen t sTable 1. Key Elements of the Safe Practice for <strong>Disclosing</strong> UnanticipatedOutcomes <strong>to</strong> <strong>Patients</strong>.*Content <strong>to</strong> be disclosed <strong>to</strong> the patientProvide facts about the eventPresence of error or system failure, if knownResults of event analysis <strong>to</strong> support informed decision making by the patientExpress regret for unanticipated outcomeGive formal apology if unanticipated outcome caused by error or system failureInstitutional requirementsIntegrate disclosure, patient-safety, and risk-management activitiesEstablish disclosure support systemProvide background disclosure educationEnsure that disclosure coaching is available at all timesProvide emotional support for health care workers, administra<strong>to</strong>rs, patients,and familiesUse performance-improvement <strong>to</strong>ols <strong>to</strong> track and enhance disclosure* Data are from the National Quality Forum.A flurry of laws concerning disclosure have beenproposed or enacted at the state and federal levels.Most prominent nationally was the proposed National<strong>Medical</strong> Error Disclosure and Compensation(MEDiC) Act of 2005, introduced by Sena<strong>to</strong>rs HillaryRodham Clin<strong>to</strong>n (D-NY) and Barack Obama(D-IL). 34 The bill was innovative in casting patientsafety and the ills of the medical liability systemas twin problems and then proposing enhancemen<strong>to</strong>f the disclosure processes as a reform withthe potential <strong>to</strong> address both. 15 The bill emphasizedopen disclosure of medical errors <strong>to</strong> patients,apology and early compensation, and a comprehensiveanalysis of the events. Congress did notpass the MEDiC Act, but its introduction indicatesthe rising profile of this issue, and similar legislationis likely <strong>to</strong> appear.State governments have pursued a greaterrange and volume of disclosure-related legislation.Seven states — Nevada, Florida, New Jersey,Pennsylvania, Oregon, Vermont, and California— have mandated that institutions disclose seriousunanticipated outcomes <strong>to</strong> patients. Pennsylvania’s2002 law was the first and arguably standsas the sternest. 35 It requires hospitals <strong>to</strong> notifypatients in writing within 7 days after a “seriousevent.” To counteract concerns about litigationexposure, the law includes a provision prohibitingthe use of such communications as evidence ofliability for the disclosed event. Interest in adoptingthis type of legal protection has been widespreadand is not limited <strong>to</strong> states with disclosuremandates. At least 34 states have adopted “apologylaws” that protect specific information conveyedin disclosures, most commonly apologies orother expressions of regret.There are good reasons <strong>to</strong> be skeptical aboutthe suitability of disclosure practices for regula<strong>to</strong>ryoversight. With respect <strong>to</strong> disclosure mandates,enforcement is a formidable challenge.Without comprehensive adverse-event reportingsystems and the substantial resources needed <strong>to</strong>audit charts and contact patients, it is extremelydifficult for regula<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>to</strong> moni<strong>to</strong>r the occurrenceof disclosures, much less their quality. To ourknowledge, none of the states that have enactedmandates have attempted serious enforcement,and only Pennsylvania actually specifies the sanctionsfor noncompliance.The content of disclosures is an especially elusivetarget for regulation. Recent research suggeststhat a key barrier <strong>to</strong> disclosure is the uncertaintyof health care workers regarding howmuch information <strong>to</strong> share with patients after adverseevents. 36 Disclosures are complex and subtlediscussions and should be tailored <strong>to</strong> the natureof the event, the clinical context, and the patient–provider relationship; as such, they are not amenable<strong>to</strong> “cookbook” rules specifying what information<strong>to</strong> disclose.In addition, there are holes in the protectionsthat many apology laws provide. Approximatelytwo thirds of the state apology laws protect onlyn engl j med 356;26 www.nejm.org june 28, 2007 2715Downloaded from www.nejm.org at HARVARD UNIVERSITY on June 29, 2007 .Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts <strong>Medical</strong> Society. All rights reserved.

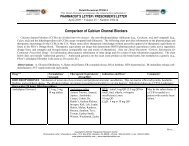

T h e n e w e ng l a nd j o u r na l o f m e dic i n ethe expression of regret, not accompanying informationrelated <strong>to</strong> causality (“our care causedyour injury”) or fault (“this should not have happened”).In addition, plaintiffs’ at<strong>to</strong>rneys, whomust sift through dozens of prospective claimsin choosing which ones <strong>to</strong> pursue, will prize informationgained from disclosures, whether ornot they are permitted <strong>to</strong> use that information asevidence in subsequent litigation. Thus, althoughapology laws are useful policy endorsements ofdisclosure, they will probably have little influenceon disclosure behavior.The potential for <strong>to</strong>p-down regulation <strong>to</strong> havea meaningful effect on disclosure conversationsis limited. The most successful disclosure initiativesare likely <strong>to</strong> be those that emerge locally, aredriven by an institutional leadership and a workforcecommitted <strong>to</strong> transparency, and focus onproviding health care workers with the skills needed<strong>to</strong> conduct these difficult conversations well.There is considerable speculation and debateabout the impact of disclosure on litigation.Patient-safety experts and proponents of disclosure<strong>to</strong>ut its litigation-reducing potential andpoint <strong>to</strong> several success s<strong>to</strong>ries (which we reviewbelow) as well as research linking poor communicationwith patients’ decisions <strong>to</strong> sue. 37-39 The actualeffect is not known and will not be evidentfor years. Overall, disclosure probably will nothave the chilling effect on litigation that someadvocates have claimed. Although disclosure mayquell some patients’ interest in litigating, it willignite interest in others, particularly those whowould never have known of their injury in the absenceof the disclosure. The net impact of disclosureon the size and cost of litigation ultimatelydepends on the balance between these twoeffects. 40Prominen t Discl osur e Pro gr a msAlthough many organizations are experimentingwith disclosure initiatives, relatively little is knownabout their effectiveness. In 1999, the VeteransAffairs Hospital in Lexing<strong>to</strong>n, Kentucky, issuedthe first published report of the effect of an opendisclosureprogram. There were no dramaticchanges in the volume of claims or the size ofpayouts after the hospital adopted the program. 14Recently, the <strong>University</strong> of Michigan Health Systemreported that the cost and frequency of litigationdecreased substantially in the 5 years afterthe implementation of an open-disclosure program,with annual litigation expenses reducedfrom $3 million <strong>to</strong> $1 million and the number ofclaims decreasing by more than 50%. 15 These twoinitiatives clearly spotlight institutions with a seriouscommitment <strong>to</strong> transparency. The data areprovocative but difficult <strong>to</strong> interpret because theyrely largely on his<strong>to</strong>rical comparison groups anddo not attempt <strong>to</strong> control for other fac<strong>to</strong>rs thatinfluence litigation rates and outcomes over time.In addition, the generalizability of the results ata single Veterans Affairs hospital and a singleacademic institution is questionable.The best-known private-sec<strong>to</strong>r disclosure programis the “3Rs” program at COPIC, a liabilityinsurer directed by physicians in Colorado. COPICinsures approximately 6000 physicians and is thelargest insurer in Colorado. In 2000, the companydeveloped a program designed <strong>to</strong> facilitatetransparent communication about injuries and expeditecompensation in selected circumstances. 41The program’s key features and outcomes arelisted in Table 2.The 3Rs program links interventions <strong>to</strong> improvecommunication with a mechanism that providespatients with up <strong>to</strong> $30,000 in compensationfor out-of-pocket health care expenses and“loss of time.” The program is “no-fault” in thatit does not tie compensation <strong>to</strong> evidence of faul<strong>to</strong>n the provider’s part. The payments are notmade in response <strong>to</strong> written demands, and patientsdo not waive their rights <strong>to</strong> sue, so 3Rspayments are not considered reportable <strong>to</strong> theNational Practitioner Data Bank.The 3Rs program has handled more than 3000events; approximately one quarter of the patientsinvolved received payments averaging $5,400 each.Seven cases in which patients were paid proceeded<strong>to</strong> litigation. Two cases resulted in additional<strong>to</strong>rt payments. Sixteen 3Rs cases that closedwithout payments were subsequently litigated; sixof the patients secured <strong>to</strong>rt compensation (LembitzA: personal communication). Although therange of cases handled by the COPIC program islimited, the outcomes suggest that these eventscan be resolved less adversarially than they mightbe by means of traditional litigation. In addition,the low average payment per incident reinforcesthe view that maximum compensation is frequentlynot the main objective for patients in the wakeof medical injury. 42Whether COPIC’s outcomes can be general2716n engl j med 356;26 www.nejm.org june 28, 2007Downloaded from www.nejm.org at HARVARD UNIVERSITY on June 29, 2007 .Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts <strong>Medical</strong> Society. All rights reserved.

current conceptsized is also not known. Colorado has enactedbroad <strong>to</strong>rt reform that provides a fertile environmentfor the 3Rs program. COPIC has long fostereda strong culture of patient-safety awarenessand early incident reporting among its insuredphysicians; this culture also may have influencedthe program’s outcomes. The 3Rs program requiresclose relationships among COPIC, theColorado Board of <strong>Medical</strong> Examiners, and theColorado Insurance Commissioner; these connectionsmay be difficult <strong>to</strong> establish elsewhere.Whether initiatives like those in the 3Rs programare feasible outside of Colorado will soonbecome evident as other insurers such as <strong>Medical</strong>Mutual in Maryland and West Virginia Mutual InsuranceCompany embark on similar programs.F u t ur e De v el opmen t sTable 2. Key Elements of COPIC’s 3Rs Program.Key featuresDisclosure linked <strong>to</strong> no-fault compensation for patient’s out-of-pocket expenses(up <strong>to</strong> $30,000)Disclosure training for physiciansExclusion criteria: death, clear negligence, at<strong>to</strong>rney involvement, complaint <strong>to</strong>state board, written demand for paymentDisclosure coaching for physician and case management for patient providedby 3Rs administra<strong>to</strong>rsPayments not reportable <strong>to</strong> National Practitioner Data BankKey outcomes (January 2000–Oc<strong>to</strong>ber 2006)2853 Colorado physicians enrolled3200 events handled in program25% of patients received payments; average, $5,400 per caseSeven paid cases subsequently litigated, two of which resulted in <strong>to</strong>rt compensation16 unpaid cases subsequently litigated, 6 of which resulted in <strong>to</strong>rt compensationDisclosure programs and practices are in their infancy.The fast pace at which they have developedover the past 5 years appears <strong>to</strong> be set <strong>to</strong> continueand perhaps even accelerate during the next 5 years.There will be ongoing experimentation with disclosureby health care delivery organizations andsome malpractice insurers. This work will yielduseful information about the impact of variousdisclosure approaches on key outcomes such aspatient satisfaction and the rates and cost of litigation.Insights gained by institutions that usestandard quality-improvement techniques <strong>to</strong> track,test, and refine their disclosure strategies will beespecially valuable. Disclosure activities continueapace outside the United States. Canada’s recentlyformed Canadian Patient Safety Institute, for example,is set <strong>to</strong> release new national disclosureguidelines, and some Canadian provinces haveadopted legislation concerning apology and disclosure.43To many practicing clinicians, the concept ofdisclosing harmful errors <strong>to</strong> patients will remainnovel and raise concerns. Research is needed <strong>to</strong>better understand patients’ preferences in relation<strong>to</strong> specific components of the disclosure discussion.19 Sophisticated investigations involving multicentercontrolled trials of training interventionsare planned, but the results are several yearsaway. Similarly, evidence of the medical and legalimplications of disclosure will remain an openquestion for the foreseeable future. Although itmay be disconcerting <strong>to</strong> individual practitioners,the absence of such an evidence base will probablynot halt the widespread implementation ofdisclosure policies and procedures. The momentumfor change is now <strong>to</strong>o great for any stakeholdergroup <strong>to</strong> brush aside demands for transparency.As organizations gain experience with disclosure,the challenges of conducting these conversationsand the need for provider education willbe increasingly apparent. 44 Eventually, most organizationswill probably provide introduc<strong>to</strong>ry disclosuretraining for their health care workers andmore intensive skills training with the use oftechniques such as simulation for clinicians whoare likely <strong>to</strong> be on the frontlines of the disclosureprocess. Many organizations will also train riskmanagers or medical direc<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>to</strong> be coaches whoprovide guidance at the time that disclosure iswarranted. Other organizations, troubled by thedifficulty of disclosures and the risks associatedwith conducting them poorly, will move the involvedclinicians <strong>to</strong> the periphery and will rely onrapid-response teams <strong>to</strong> conduct disclosures. Itremains <strong>to</strong> be seen whether the benefits of theuse of disclosure “pinch hitters” will outweighthe potential harm <strong>to</strong> the clinician–patient relationship.Additional national organizations and specialtysocieties may follow the NQF’s lead and disseminatedisclosure standards. Key uncertaintiesabout disclosure practice include the effect of disclosureon patient satisfaction and claiming behaviorand the role of apology and acceptance ofn engl j med 356;26 www.nejm.org june 28, 2007 2717Downloaded from www.nejm.org at HARVARD UNIVERSITY on June 29, 2007 .Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts <strong>Medical</strong> Society. All rights reserved.

T h e n e w e ng l a nd j o u r na l o f m e dic i n eresponsibility in disclosure. Until research helps<strong>to</strong> resolve these uncertainties, most disclosurestandards will remain advisory and general innature. This paucity of evidence is also likely <strong>to</strong>prevent the Joint Commission from issuing moredetailed disclosure standards and tying their fulfillment<strong>to</strong> accreditation. Although additionallegislative activity is likely, most of it will begeared <strong>to</strong>ward providing incentives for disclosureor penalizing failures <strong>to</strong> disclose, and the regula<strong>to</strong>ryimpact will be modest. In the short term,voluntary standards coupled with pay-for-performance–typeincentives represent the best hopefor making substantive improvements in disclosure.Reactions <strong>to</strong> the NQF’s new disclosurestandard — in terms of payers’ interest in it as aperformance measure and how willing they are<strong>to</strong> use it in commercial decisions — will providean early field test of this approach.A transformation in how the medical professioncommunicates with patients about harmfulmedical errors has begun. Within a decade, fulland frank disclosure of these events <strong>to</strong> patients islikely <strong>to</strong> be the norm rather than the exception.Making disclosure of harmful errors <strong>to</strong> patientsan expectation in medicine and giving providersthe <strong>to</strong>ols <strong>to</strong> turn this principle in<strong>to</strong> practice mayprove <strong>to</strong> be critical steps in res<strong>to</strong>ring the public’strust in the honesty and integrity of the healthcare system.Supported by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Researchand Quality (1K08HS01401201) and the Greenwall Faculty Scholarsin Bioethics Program — both <strong>to</strong> Dr. Gallagher.No potential conflict of interest relevant <strong>to</strong> this article wasreported.We thank Alan Lembitz, M.D., Richert Quinn, M.D., and DennisBoyle, M.D., for information on COPIC’s 3Rs program; Eric B.Larson, M.D., M.P.H., Michelle M. Mello, J.D., Ph.D., and CharlesR. Denham, M.D., for their insightful comments on the manuscript;and Carolyn Prouty, D.V.M., for assistance with manuscriptpreparation.References1. Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al.Incidence of adverse events and negligencein hospitalized patients: results of the <strong>Harvard</strong><strong>Medical</strong> Practice Study I. N Engl JMed 1991;324:370-6.2. Wilson RM, Runciman WB, GibberdRW, Harrison BT, Newby L, Hamil<strong>to</strong>n JD.The Quality in Australian Health CareStudy. Med J Aust 1995;163:458-71.3. Thomas EJ, Studdert DM, Burstin HR,et al. Incidence and types of adverse eventsand negligent care in Utah and Colorado.Med Care 2000;38:261-71.4. Vincent C, Neale G, WoloshynowychM. Adverse events in British hospitals:preliminary retrospective record review.BMJ 2001;322:517-9. [Erratum, BMJ 2001;322:1395.]5. Schioler T, Lipczak H, Pedersen BL,et al. Incidence of adverse events in hospitals:a retrospective study of medicalrecords. Ugeskr Laeger 2001;163:5370-8.(In Danish.)6. Davis P, Lay-Yee R, Briant R, Ali W,Scott A, Schug S. Adverse events in NewZealand public hospitals I: occurrence andimpact. N Z Med J 2002;115:U271.7. Baker GR, Nor<strong>to</strong>n PG, Flin<strong>to</strong>ft V, et al.The Canadian Adverse Events Study: theincidence of adverse events among hospitalpatients in Canada. CMAJ 2004;170:1678-86.8. Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM, Brodie M,et al. Views of practicing physicians andthe public on medical errors. N Engl J Med2002;347:1933-40.9. Mazor KM, Simon SR, Yood RA, et al.Health plan members’ views about disclosureof medical errors. Ann Intern Med2004;140:409-18.10. National survey on consumers’ experienceswith patient safety and qualityinformation. Kaiser Family Foundation/Agency for Healthcare Research andQuality/<strong>Harvard</strong> School of Public Health,2004. (Accessed June 1, 2007, at http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/upload/National-Survey-on-Consumers-Experiences-With-Patient-Safety-and-Quality-Information-Survey-Summary-and-Chartpack.pdf.)11. Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, EbersAG, Fraser VJ, Levinson W. <strong>Patients</strong>’ andphysicians’ attitudes regarding the disclosureof medical errors. JAMA 2003;289:1001-7.12. Witman AB, Park DM, Hardin SB. Howdo patients want physicians <strong>to</strong> handle mistakes?A survey of internal medicine patientsin an academic setting. Arch InternMed 1996;156:2565-9.13. Safe practices for better healthcare.Washing<strong>to</strong>n, DC: National Quality Forum,2007. (Accessed June 1, 2007, at http://www.qualityforum.org/projects/completed/safe_practices/.)14. Kraman SS, Hamm G. Risk management:extreme honesty may be the bestpolicy. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:963-7.15. Clin<strong>to</strong>n HR, Obama B. Making patientsafety the centerpiece of medical liabilityreform. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2205-8.16. Wei M. Doc<strong>to</strong>rs, apologies, and thelaw: an analysis and critique of apologylaws. J Health Law 2007. (Accessed June 1,2007, at http://ssrn.com/abstract=955668.)17. Lazare A. Apology in medical practice:an emerging clinical skill. JAMA 2006;296:1401-4.18. Australian Council for Safety andQuality in Health Care. Open disclosurestandard: a national standard for opencommunication in public and private hospitalsfollowing an adverse event in healthcare— 2003 update. (Accessed June 1,2007, at http://www.safetyandquality.org/internet/safety/publishing.nsf/Content/F87404B9B00D8E6CCA2571C60000F049/$File/OpenDisclosure_web.pdf.)19. Safer practice notice: being open whenpatients are harmed. London: NationalPatient Safety Agency, 2005. (Accessed June1, 2007, at http://www.npsa.nhs.uk/site/media/documents/1314_SaferPracticeNotice.pdf.)20. Gallagher TH, Levinson W. <strong>Disclosing</strong>harmful medical errors <strong>to</strong> patients: a timefor professional action. Arch Intern Med2005;165:1819-24.21. Gibson R, Singh JP. Wall of silence:the un<strong>to</strong>ld s<strong>to</strong>ry of the medical mistakesthat kill and injure millions of Americans.Washing<strong>to</strong>n, DC: Lifeline Press, 2003.22. Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, GarbuttJM, et al. US and Canadian physicians’ attitudesand experiences regarding disclosingerrors <strong>to</strong> patients. Arch Intern Med2006;166:1605-11.23. Snyder L, Leffler C. Ethics manual:fifth edition. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:560-82.24. AHA management advisory: ethicalconduct for health care institutions. Chicago:American Hospital Association, 1992.25. American <strong>Medical</strong> Association Councilon Ethical and Judicial Affairs, SouthernIllinois <strong>University</strong> at CarbondaleSchool of Law. Code of medical ethics, annotatedcurrent opinions: including theprinciples of medical ethics, fundamental2718n engl j med 356;26 www.nejm.org june 28, 2007Downloaded from www.nejm.org at HARVARD UNIVERSITY on June 29, 2007 .Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts <strong>Medical</strong> Society. All rights reserved.

current conceptselements of the patient-physician relationshipand rules of the Council on Ethicaland Judicial Affairs. 2004-2005 ed. Chicago:American <strong>Medical</strong> Association, 2004.26. The Joint Commission. Hospital accreditationstandards, 2007. OakbrookTerrace, IL: Joint Commission Resources,2007.27. Health care at the crossroads: strategiesfor improving the medical liabilitysystem and preventing patient injury. JointCommission on Accreditation of HealthcareOrganizations, 2005. (Accessed June1, 2007, at http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/3F1B626C-CB65-468B-A871-488D1DA66B06/0/medical_liability_exec_summary.pdf.)28. Lamb RM, Studdert DM, Bohmer RM,Berwick DM, Brennan TA. Hospital disclosurepractices: results of a national survey.Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22(2):73-83.29. Gallagher T, Brundage G, Bommari<strong>to</strong>KM, et al. Risk managers’ attitudes andexperiences regarding patient safety anderror disclosure: a national survey. ASHRMJournal 2006;26:11-6.30. When things go wrong: responding <strong>to</strong>adverse events: a consensus statement ofthe <strong>Harvard</strong> Hospitals. Bos<strong>to</strong>n: MassachusettsCoalition for the Prevention of <strong>Medical</strong><strong>Errors</strong>, 2006.31. Flynn E, Jackson JA, Lindgren K, MooreC, Ponia<strong>to</strong>wski L, Youngberg B. Shiningthe light on errors: how open should webe? Oak Brook, IL: <strong>University</strong> HealthSystemConsortium, 2002.32. The National Quality Forum safe practicesleap. Washing<strong>to</strong>n, DC: The LeapfrogGroup, 2007. (Accessed June 1, 2007, athttp://www.leapfroggroup.org/media/file/Leapfrog-National_Quality_Forum_Safe_Practices_Leap.pdf.)33. Welcome <strong>to</strong> the Leapfrog HospitalQuality and Safety Survey results. Washing<strong>to</strong>n,DC: The Leapfrog Group, 2007.(Accessed June 1, 2007, at http://www.leapfroggroup.org/cp.)34. The National <strong>Medical</strong> Error Disclosureand Compensation Act 2005; S. 1784, 109thCongress; 2005.35. In: 40 Pa Cons Stat Ann; 2002.36. Gallagher TH, Garbutt JM, WatermanAD, et al. Choosing your words carefully:how physicians would disclose harmfulmedical errors <strong>to</strong> patients. Arch InternMed 2006;166:1585-93.37. Hickson GB, Clay<strong>to</strong>n EW, Githens PB,Sloan FA. Fac<strong>to</strong>rs that prompted families<strong>to</strong> file medical malpractice claims followingperinatal injuries. JAMA 1992;267:1359-63.38. Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, DullVT, Frankel RM. Physician-patient communication:the relationship with malpracticeclaims among primary care physiciansand surgeons. JAMA 1997;277:553-9.39. Vincent C, Young M, Phillips A. Whydo people sue doc<strong>to</strong>rs? A study of patientsand relatives taking legal action. Lancet1994;343:1609-13.40. Studdert DM, Mello MM, GawandeAA, Brennan TA, Wang YC. Disclosure ofmedical injury <strong>to</strong> patients: an improbablerisk management strategy. Health Aff(Millwood) 2007;26:215-26.41. Gallagher TH, Quinn R. What <strong>to</strong> dowith the unanticipated outcome: doesapologizing make a difference? How doesearly resolution impact settlement outcome?In: <strong>Medical</strong> liability and health carelaw seminar. Phoenix: Defense ResearchInstitute, 2006.42. Bismark M, Dauer E, Paterson R,Studdert D. Accountability sought by patientsfollowing adverse events from medicalcare: the New Zealand experience.CMAJ 2006;175:889-94.43. Background paper for the developmen<strong>to</strong>f national guidelines for the disclosureof adverse events. Edmon<strong>to</strong>n, AB, Canada:Canadian Patient Safety Institute, 2006.(Accessed June 1, 2007, at http://www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca/resources/publications_new.html.)44. Amori G. Pearls on disclosure ofadverse events. Chicago: American Societyfor Healthcare Risk Management,2006.Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts <strong>Medical</strong> Society.electronic access <strong>to</strong> the journal’s cumulative indexAt the Journal’s site on the World Wide Web (www.nejm.org),you can search an index of all articles published since January 1975(abstracts 1975–1992, full text 1993–present). You can search by author,key word, title, type of article, and date. The results will include the citationsfor the articles plus links <strong>to</strong> the full text of articles published since 1993.For nonsubscribers, time-limited access <strong>to</strong> single articles and 24-hour siteaccess can also be ordered for a fee through the Internet (www.nejm.org).n engl j med 356;26 www.nejm.org june 28, 2007 2719Downloaded from www.nejm.org at HARVARD UNIVERSITY on June 29, 2007 .Copyright © 2007 Massachusetts <strong>Medical</strong> Society. All rights reserved.