Creating a Mentoring Programme for Sport: A ... - sports coach UK

Creating a Mentoring Programme for Sport: A ... - sports coach UK

Creating a Mentoring Programme for Sport: A ... - sports coach UK

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Влияние изменения климатана экосистемыбассейна реки АмурClimate Change Impacton Ecosystemsof the Amur River Basin

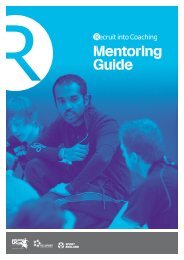

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>1Section 1IntroductionThis guide has been developed to help you design, set up andimplement a mentoring programme suited to the <strong>coach</strong>ing needsof your context (eg governing body of sport, county <strong>sports</strong>partnership [CSP], local <strong>coach</strong>ing network, club environment).It has been developed in collaboration with a variety ofprofessionals and practitioners in the area of mentoring andcontains practical guidance to get your programme up and running.It contains best-practice in<strong>for</strong>mation, practical tips,prompt questions and sample material that you canadapt to your context. All examples have beendrawn from successful mentoring programmes andwill support the development of a programme orenhance your existing programme to ensure safeand effective practice and positive outcomes.Why embark on amentoring programme?Interest in mentoring has grown over time as werecognise the benefits it brings. <strong>Mentoring</strong> really issomething that can benefit everyone. As well ashelping the mentee develop and advance, thementor can gain extra skills and understandingfrom the partnership. In addition, your organisationcan benefit from improved retention of adynamic work<strong>for</strong>ceBenefits of being a mentee• Gain practical advice, encouragementand support.• Learn from the experiences of others.• Become more resourceful and able to copewith critical incidents.• Become more empowered to make decisions.• Develop social confidence, communication andpersonal skills.Benefits of being a mentor• Develop leadership and management qualities.• Increase confidence and motivation.• Engage in a volunteering opportunity,valued by others.• Benefit from a sense of fulfilment andpersonal growth.• Satisfaction in being able to contribute tosomeone else’s growth.Benefits of mentoring to an organisation• Enhanced transfer of skills leading toproductivity gains.• Increased on-the-job learning that reducesoff-the-job training costs.

4<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>1The outcomeThe first question to be asked should be ‘What dowe need?’The first answer to be found should be ‘What do wewant it to achieve?’Many mentoring programmes start out with thewell-meaning but vague aim of ‘helping the <strong>coach</strong>esimprove’. Experience suggests that the sharper thefocus of the mentoring programme, the clearerthose involved are likely to be regarding their roleand, in turn, success will be more easily evaluated.The justificationThe decision to implement a programme should bebased on a robust audit of your <strong>coach</strong>ingdevelopment infrastructure and where the greatestneed lies or the greatest impact may be. This reallydemands an evidence-based and needs-led decisionrather than a few people simply having a meetingand deciding what they think is best <strong>for</strong>their <strong>coach</strong>es.The work<strong>for</strong>ceThe focus of your programme will in<strong>for</strong>m thedecision regarding which <strong>coach</strong>es and mentors willbe invited to participate in the programme, as wellas who may be best-placed to manage the overallprogramme. You will make decisions about how toset up and run your mentoring programme basedon your own infrastructure and resources available.Regarding payments or other incentives beingoffered to the people involved, mentors havegenerally been offered some type of reward, financialor otherwise (eg match/event tickets, <strong>sports</strong>clothing/equipment or free professionaldevelopment opportunities, expenses).When deciding on the specific policy on payment<strong>for</strong> mentors, the general options to consider are:• payment of a nominal sum to cover expensesand duties, paid on completion of any specifiedduties (eg a certain number of mentoringmeetings and/or the submission of amentoring record)• expenses only to be paid as appropriate onreceipt of mileage or other claims• no direct payment but recognition of thementor’s work via other incentives – this may sitmore easily with some <strong>sports</strong> (eg <strong>sports</strong>clothing/equipment or tickets <strong>for</strong> events)• no payment but increasing the perceived valueof the role through publicising the benefits ofbecoming a mentor, resulting in people strivingto be one of this perceived high status orelite work<strong>for</strong>ce.The <strong>for</strong>matHaving decided on the outcome, rationale andpeople involved, the <strong>for</strong>mat and structure of theprogramme need to be considered. Keyconsiderations when planning the structure andtiming are:• the <strong>coach</strong>ing season – this in<strong>for</strong>ms when tostart, review and conclude the programme• the matching of mentors and <strong>coach</strong>es(eg skills-led or geographical?)• the ratio of mentors to <strong>coach</strong>es – how many<strong>coach</strong>es can/should be allocated to one mentor• what training and orientation will be neededand how best to structure this• suggested frequency and/or number ofmentoring interventions• degree of emphasis to be placed onface-to-face meetings, direct observation andfeedback on <strong>coach</strong>ing practice• ongoing support and communication tocheck progress.The time frameThe time frame over which your programme willoperate will vary. This will ultimately depend onthings like funding, season length and level ofsupport available to the project on an ongoing basis.An example of how a programme may bestructured is set out on the next page:

8<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>2Typically, research literature states that mentoring isan ongoing, prolonged process that includes regularinteraction between the mentor and mentee(eg face-to-face contact, email, phone, sessionobservations, workshops and networking). It isrecognised as offering both structured andunstructured support <strong>for</strong> <strong>coach</strong> learning and is themost visible example of a practice where <strong>for</strong>mal andin<strong>for</strong>mal learning meet.Among the many definitions, a common emphasisappears to be placed on the guiding function, andmost include verbs like support, advise, nurture andfacilitate. <strong>Mentoring</strong> is there<strong>for</strong>e seen as doingsomething with the mentee, nurturing andsupporting learning, and it is an investment in thetotal personal growth of the individual.Successful mentoring programmesThe most effective mentoring programmes existwithin organisations that have given matureconsideration to the reasons <strong>for</strong> employingmentoring. It seems the successful programmespossess a number of key elements. Central to theirsuccess is a single coordinating body withresponsibility <strong>for</strong> the areas in the diagram below.Some rewardsystem <strong>for</strong> thementor andmenteeThe recruitment,training anddeployment ofmentors/menteesThe managementprocess as a wholeMaintainingan element ofstructure/communication(over an extendedperiod)SuccessfulmentoringprogrammesFacilitating thematching ofmentors withmenteesClear goalsand outcomesThe establishmentof clear roles andresponsibilities

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>9The mentorMentors are most effective when they are fullyaware of the role they are required to fulfil. Whetherthis is to support personal or professional growth,there is a real need <strong>for</strong> mentors to have their roleclearly defined. More importantly, the mentee mustshare the interpretation of this role.The mentor’s primary function is that of atransitional figure, supporting the mentee throughdifficult periods, eliciting positive change inknowledge, work or thinking. In such a model, thementor questions the mentee to stimulate reflectionand plays a critical role in creating a safeenvironment where mistakes can be made andlearning can occur.So what is a mentor?Descriptive statements regarding what a mentoris include:• the provider of opportunity not normallyextended to <strong>coach</strong>es• the supplier of insider in<strong>for</strong>mation, privilegedand generally not known to others• a challenger who evokes reflection anddeeper thinking• a believer in potential.The mentor’s remit within some contexts mayextend to:• exploring the personal views and relatedanxieties of the individual in a new role• assisting with integrating the mentee into their<strong>coach</strong>ing environment• providing guidance in relation to where helpfulresources can be accessed• assisting with the preparation and delivery ofrole-based tasks• guiding practice and indicatingappropriate, alternative strategieswithin a supportive framework.<strong>Mentoring</strong> is also an instrument of socialisationwherein mentors control the gates to social learning.Being introduced to existing communities ofpractising <strong>coach</strong>es provides mentees with a valuableinsight into the dos and don’ts of their profession.The <strong>coach</strong>’s view of mentorsCoaches value this <strong>for</strong>m of support if they seementors as credible and willing to allow in<strong>for</strong>mationexchange. Previous research 1 has found that <strong>coach</strong>eshave the following expectations of mentors:The ‘ideal’ <strong>sports</strong> <strong>coach</strong> mentor is expected to have:• good sport-specific technical knowledge• good knowledge of the <strong>coach</strong>ing process• credibility, through qualifications and/orexperience in <strong>coach</strong>ing and mentoring• good communication skills, particularlyquestioning and listening• good interpersonal skills, particularly openness,approachability, support and empathy(emotional intelligence)• the ability to guide mentees in their learning andfacilitate self-actualisation (help them achievewhat they truly want in life)• a professional approach to mentoring.It is important to note that a <strong>coach</strong>’s expectationschange over time. As they become moreexperienced, the support they require and look<strong>for</strong> changes. There is often a move away fromsport-specific technical in<strong>for</strong>mation and the need <strong>for</strong>feedback on <strong>coach</strong>ing per<strong>for</strong>mance toward a need<strong>for</strong> more sport science and <strong>coach</strong>ing processknowledge, as well as readiness to be challenged andencouraged to reflect.The mentoring relationshipWhether the most successful mentoringrelationships are those that are naturally occurring,self-selecting or <strong>for</strong>mally allocated is still up <strong>for</strong>debate. What is clear is that each and everymentor:mentee relationship is unique. Seen as ahelping relationship, it involves the ability and desireto understand a person’s meaning and feelings(their situational context) without being overlyemotionally involved.To be effective, relationships should be holistic inthat they emphasise both positive growth anddevelopment of the individual as a <strong>coach</strong> andperson. Basic ingredients such as respect, empathy,honesty, acceptance, responsiveness, cooperationand positive regard are all cited as important. Theemphasis within the relationship is placed onlistening, questioning and enabling, as opposed totelling and directing.21Institute <strong>for</strong> Vocational and Exercise and <strong>Sport</strong> Training (2007) Evidencing the Development of <strong>Sport</strong> Coach <strong>Mentoring</strong> Training, Qualification andDeployment. Cardiff: Cardiff School of <strong>Sport</strong>.

10<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>2An ideal mentoring relationship is considered to bea reciprocal one in which both parties gain in someway from the experience. There<strong>for</strong>e, a positivementoring relationship can be characterised by:• sharing – of ideas, knowledge, expertise,resources, beliefs and values• mutual respect – reciprocal value <strong>for</strong>knowledge, expertise and interpersonal skills(how they deal with people and situations)• mutual trust – a sense of safety and anenvironment within which shortcomings can beshared without judgement; a faith, confidenceand belief in each other• reciprocity – of learning and investment inthe relationship• care and concern – directed towards personaland professional development.The relationship process<strong>Mentoring</strong> can be viewed as a process, consisting ofa series of interactions from which <strong>coach</strong>es canexpect to gain new skills and knowledge, andfeedback on per<strong>for</strong>mance. This process is atransitional phenomenon that varies in intensity anddepth as it evolves over time, consisting of threefeatures: initiation; transition; and ending.• Initiation – This generally occurs when thementee is in a new, challenging position orduring a significant shift in their development.The impetus to engage in a mentoring exchangeoften occurs naturally when a mentee and anexpert (mentor) are inadvertently drawntogether, usually as a result of some mutualinterest or goal.• Transition – As the mentorship develops, thereappears to be a shift whereby the mentee gainsa better sense of capability (confidence andself-belief) and is able to engage in/contribute tothe process more actively. This trans<strong>for</strong>mationalshift sees the mentee give back to therelationship, and reciprocal learning occurs.• Ending – Ideally, the mentorship only ends whenneither mentee nor mentor has a need <strong>for</strong> it tocontinue. The established nature and structureof their relationship is substantially changed,either by increasing physical or psychologicaldistance.It should be noted that these stages don’t alwaysarrive in a logical, clean sequence.© Alan Edwards

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>11Building relationshipsBuilding rapport and understanding is at the heart of developing a good working relationship betweenmentor and mentee. Relevant knowledge, understanding and skills will certainly go a long way to help, but youwill also need to demonstrate a real commitment to the process through behaviour that reflects your genuineinterest and values. Hildebrand (2007) 2 identified four areas that contribute to building rapport between amentee and mentor:21 CommonalitiesShared ideas, traits and interests will develop arelationship on a common, shared foundation.Finding these commonalities will involvesharing and communication.2 ConnectivityOnce sharing has taken place andcommonalities have been discovered, aconnection will be made.3 CommunicationDeveloping rapport through communication isnot simply the words you use. It involves bodylanguage, gestures and eye contact.4 CollaborationYou must develop shared approaches tothe structure, outcomes and approach toyour relationship.Figure 2: The 4Cs <strong>for</strong> building rapportWe recognise that relationships do not develop overnight and will take time to cultivate. Powell (1998) 3suggests there are five levels or stages to developing truly effective communication. These are rituals andclichés, facts and in<strong>for</strong>mation, ideas and judgements, feelings and emotions, and peak rapport.IncreasedRiskPeakRapportFeelings andEmotionsIdeas andJudgementsFacts andIn<strong>for</strong>mationCommunication is intuitive. You feelsafe to reveal your unique needs.This usually occurs when people donot worry about convention. Youfeel safe to share deeper emotions.People express themselves interms of concerns, expectationsgoals and desires.Little personal in<strong>for</strong>mation is revealedand relates to factual in<strong>for</strong>mation,which requires no depth in thinking.5432DecreasedRiskRituals andClichésFigure 3: Levels of communication(adapted from Powell, 1998)Rote patterns of speaking.Typical, habitual questions withno real genuine intent.12Hildebrand, S.D. (2007) ‘Building solid work relationships: developing rapport with co-workers’, http://deborah-s-hildebrand.suite101.com/building-solid-work-relationships-a338523Powell, J. (1998) Why Am I Afraid to Tell You Who I Am? Resources <strong>for</strong> Christian Living. ISBN: 978-0-883473-23-8.

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>13discrete tasks or proficiencies and whether this willinclude the tacit knowledge that underpins the role.3 The Reflective Practitioner Model is based onthe premise that mentees learn best when theyself-reflect and critique their own per<strong>for</strong>mance.This is typically done through structuredquestioning and is considered a valuable way <strong>for</strong>individuals to analyse and evaluate practicalexperience, enabling them to subsequently learnfrom it. The role of the mentor in this model isto question the mentee in such a way as tostimulate reflection. However, this model is notgenerally liked by mentees because of itsdemanding nature. Inexperienced mentees don’tseem to like this approach because they have towork and are not just given the answers.StructureMarshall (2001) 5 identified three mentoring modelswith regard to structure: supervisory (<strong>for</strong>mal);in<strong>for</strong>mal; and facilitated. Each <strong>for</strong>mat falls along acontinuum, from those that are very short term andin<strong>for</strong>mal to highly structured, long-term partnerships.1 Supervisory or <strong>for</strong>mal mentoring usually takesplace in a work environment and is consideredto be a function of a supervisor’s duties. This<strong>for</strong>m of mentoring predominantly relies on theability of the supervisor to communicateknowledge about the job. This model could beproblematic in that there is an element ofline-management responsibilities withinthis relationship.2 In contrast, in<strong>for</strong>mal mentoring is based onthe natural pairing of two individuals,characteristically based on some <strong>for</strong>m of mutualchemistry and trust, and typically initiated by thementee. They would typically select an individualwho they felt could assist them in theirdevelopment and work with them accordingly.3 Facilitated mentoring attempts to replicate andbuild on the benefits of in<strong>for</strong>mal mentoring. Thismodel is typically based around a morestructured design incorporating a strategicallyplanned mentoring programme, facilitatedmatching, developmental training, a no-faulttermination culture, a <strong>for</strong>malised careerdevelopment plan and a programmecoordinator whose primary roles are toimplement the programme, match the pairs andmonitor progress and evaluate.RelationshipYoung et al. (2005) 6 identified three relativelydistinct but general patterns in the fundamentalnature of the relationships between mentors andtheir mentees:1 Directive – The directive mentor takes charge,sets the agenda, has a clear expectation <strong>for</strong>mentee per<strong>for</strong>mance and seeks, through avariety of means, to guide the mentee andencourage corrective action. At the extreme, thedirective mentor models specific teachingstrategies and behaviours with the firmexpectation that the mentee will emulate them.Feedback takes the <strong>for</strong>m of strongrecommendations or directives, not suggestionsor possibilities <strong>for</strong> consideration. The directivementor assumes a role of master teacher, guideand sometimes <strong>coach</strong>. This type of mentoringmodel is referred to as hierarchical and is mostappropriate early on in a mentoring relationship,especially if the mentee is a novice in making useof supervision.2 Interactive – In the purest <strong>for</strong>m of thisrelationship, the interactive mentor seeks arough relational parity (equality between thementor and mentee), characterised by openconversation on issues of mutual concern, withthe mentor acting as a friend, colleague andtrusted adviser. Relationships exist only whenthe mentor and mentee recognise each other insome sense as peers, that each brings to therelationship distinctive and valuablecontributions. The agenda is jointly <strong>for</strong>med andadjusted in response to the interests and desiresof either mentor or mentee. This <strong>for</strong>m ofrelationship is most appropriate <strong>for</strong> the moreexperienced mentee and as the mentoringrelationship becomes established.3 Responsive – At the extreme, the responsivementor looks almost exclusively to their mentee<strong>for</strong> guidance and direction. The mentee sets theagenda by posing questions or presentingproblems and concerns <strong>for</strong> the mentor’sconsideration. The object here is to createconditions within which mentees can exercisefull control over the relationship using reflection,empathy and peer-to-peer questioning in orderto generate answers to problems.In practice, effective mentors will move appropriatelybetween the models in relation to purpose,structure and relationship in response to thementee’s needs. Mentors will develop their ownunique style, playing to their strengths and adaptingtheir approach according to the circumstancesof mentees.5Marshall, D. (2001) ‘<strong>Mentoring</strong> as a developmental tool <strong>for</strong> women <strong>coach</strong>es’, Canadian Journal <strong>for</strong> Women in Coaching, 2 (2): 1–10.6Young, J.R., Bullough, R.V. Jr, Draper, R.J., Smith, L.K. and Erickson, L.B. (2005). ‘Novice teacher growth and personal models of mentoring: choosingcompassion over inquiry’, <strong>Mentoring</strong> and Tutoring, 13 (2) 169–188.2

14<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>1

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>15Section 3<strong>Programme</strong> Designand DevelopmentThis section is very much about getting your programme off theground. Key to this is starting with the need – what do <strong>coach</strong>esneed? Sometimes, this is obvious and quite straight<strong>for</strong>ward.However, sometimes, what you think is needed may not be thecase. It is important that you consult with those you intend tosupport so we have provided some prompt questions to guideyou. The remainder of this section is geared toward planning <strong>for</strong>success, looking at feasibility, business proposals and roadmap planning.Start with the needThis section is intended to help you with the set up, management, implementation and evaluation of yourmentoring programme.Identify needRefine serviceProject demandCheck feasibilityBuildbusiness caseWhat is theproblem youare trying tosolve?What domenteesneed?What is thedemand(consult)?Considerwork<strong>for</strong>ce,<strong>for</strong>mat andtime frame.Plan <strong>for</strong>delivery.Figure 5: Key phases in programme design and development

16<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>3Your decision to set up a mentoring programme willno doubt stem from the belief that a need exists.Be<strong>for</strong>e you begin, you will need to verify if this isactually the case. The first part of programme designis to ask the questions: ‘What evidence exists tosupport the creation of a mentoring programme?’and ‘Is mentoring the answer?’It may help to narrow down the possible optionsregarding the service you wish to offer by answeringthe following questions be<strong>for</strong>e going further:• What geographical area is to be covered by theprogramme (local, regional, national)?• What type of <strong>coach</strong> support services do youintend to offer (<strong>coach</strong> education, training,supported practice, focused mentoring, howoften, <strong>for</strong> how long)?• Who is your target audience that would benefitfrom this?• What support exists <strong>for</strong> the implementation ofa mentoring programme from within yourorganisation, including resources available (bothfinancial and human)?Estimating demandIf you haven’t already, take a look at the initialquestions posed within the introduction (page 6).Once you have considered these and answered thebasic questions above, it is time to get out into your<strong>coach</strong>ing community to investigate their needs. Youare looking not only <strong>for</strong> the challenges and problemsfacing <strong>coach</strong>es, but also the existing support/servicesavailable to them. These may be provided nationallyor on a more localised level, through governingbodies of sport, CSPs, charitable organisations,educational institutions etc.By comparing their needs with the services currentlybeing provided, you will be able to determine thegap in provision that your programme could/shouldaddress. This needs assessment will give you the ‘bigpicture’ of what is happening in your <strong>coach</strong>ingcommunity and help focus the role you and yourorganisation might play. You may actually find thatgood support systems already exist and what ismissing is the connection between those in need(the <strong>coach</strong>es) and those who provide the service!ConsultingIn your assessment of need, you should include inputfrom as much of the <strong>coach</strong>ing community andsurrounding infrastructure as possible, includingathletes, <strong>coach</strong>es, clubs, committee members, andcurrent and prospective mentors, along with otherspecific agencies (eg disability groups, volunteerorganisations and governing bodies of sport).Thisconsultation process may take the <strong>for</strong>m ofquestionnaires, interviews and/or focus groups.Below are some example questions you could askvia one of these methods.• What do you believe mentoring to be?• If we were to develop and implement a <strong>for</strong>malmentoring programme, how do you believe youwould benefit?• What do you think the impact of mentoringcan be?• Would you participate as a mentee?• Are you available to be a mentor?• What specific knowledge, skills and abilitieswould you look <strong>for</strong> in a mentor and/or mentee?• Do you already have access to mentors? If so,please describe how this mentoring programmeworks and any benefits you get frombeing involved.• What kinds of activities would you like to see aspart of a mentoring programme?• Do you utilise other career developmentactivities provided (eg workshops)? If so, pleasedescribe what these are and how you havebenefited from them.It is important to be clear about the nature of theservice you would like to offer, and conducting aconsultation event with those who will access theservice is a great way to do this. It will help yourefine the outcomes you wish to achieve, along withthe specific needs and characteristics of the targetgroup you will work with.Feasibility assessmentUsing the responses you receive from yourconsultation exercise, you can begin to undertake afeasibility assessment. Some prompt questions tohelp you determine the feasibility of the programmeare provided below.What type of support do your <strong>coach</strong>eswant/need?What barriers exist to the programme and howdo you intend to overcome them?Does anyone in your area provide asimilar service?How will you attract mentors and mentees?Do you have the capability and capacity to deliverthe service your <strong>coach</strong>es require?What do you expect the demand <strong>for</strong> your serviceto be (eg number of <strong>coach</strong>es using theprogramme per year)?What will the service cost you and yourmentors/mentees?What are your timescales <strong>for</strong> this project?

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>17If your feasibility assessment is favourable, the nextstep is to develop a business plan. This will help youmanage and oversee the programme’s activities andoutcomes. It can also help to provide a basis <strong>for</strong>securing funding.Example contents of a business planA business plan should include the findings of thefeasibility assessment, a project plan/timeline with keymilestones, and the programme description, alongwith the following:• executive summary• goal(s) of the mentoring programme(aims and objectives)• success factors and desired outcomes• target population• duration of the programme• benefits to mentors and mentees• benefits to the organisation (eg increasedmorale, transfer of knowledge)• how the organisation plans to market theprogramme and recruit mentors and mentees• budgets, including staffing costs (incomeand expenditure)• mentee/mentor matching process• outline of the orientation session• types of materials provided to mentors,mentees and supervisors• potential mentoring and career developmentactivities (eg training)• management structure (staff requirements anddecision making)• process <strong>for</strong> monitoring and evaluating thementoring process.Planning <strong>for</strong> successOne of the major reasons <strong>for</strong> programme failure islack of preparation. Do not neglect the planningprocess because you want to get the project up andrunning in the shortest time possible. Experiencetells us that setting up a mentoring programme israrely a quick process, and the success of aprogramme relies on the time spent on preparation.By identifying who owns the plan, it will be evidentwho will be held accountable and who is in place tomake the vital decisions at each stage of theprogramme’s development. It is also extremelyimportant to identify whose support is required <strong>for</strong>the programme to proceed. Without their support,it may never go beyond the planning stage. Use thisexercise to identify and record the names of allthose relevant to the design and delivery of the plan– who needs to be involved and <strong>for</strong> what reason.Who initiated the plan? (Idea generator)Who is the project sponsor?(This person will often bethe budget holder anddecision maker.)Who owns the design anddelivery of the plan? (This isoften the operational team thatwill manage implementation.)Who needs to be influenced ifthe plan is to be successful?(Consider your executivemanagement team.)Which stakeholders need tounderstand their partin/contribution to the delivery ofthe plan? (These may be bothinternal and external people.)Road map planning(Budget holder)(Project/programmecoordinator)(Executivemanagementteam)(External trainingproviders,mentors etc)<strong>Creating</strong> a road map <strong>for</strong> your mentoring programmecan act as a framework <strong>for</strong> delivery, evaluation andfuture improvement. This road map will set thedirection but can and should be modified ascircumstances change and experiences dictate.This approach to planning uses a systematic processto describe the sequence of events that starts withyour need and leads to the achievement of yourprogramme outcomes. A simple example of thisprocess is depicted below.3NeedResources/inputsActivitiesOutputsIntermediateoutcomes(1–5 years)Impact/long-termoutcomesThe problem(s)yourprogrammewill address<strong>Programme</strong>ingredients, suchas funds, staff,volunteers,partnersSpecificactivities andservicesthe programmewill provideSpecificevidence ofservicesprovided(numbers)Positivechanges thatwill take placeas a result ofservicesLasting andsignificantresults of yourprogramme overthe long term

18<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>3When building your road map, it is often helpful totackle each element in the following order:1 What is the problem you are trying to solve?(What is the current situation that you intendto impact on?)2 What will success look like? (What is thedesired outcome/behaviour change?)3 What knowledge, skills or experiences dopeople need be<strong>for</strong>e behaviour change mayoccur? (There<strong>for</strong>e, what activities/services doyou need to deliver/provide?)4 How much activity is enough to promotechange? (What outputs are you looking <strong>for</strong>?)5 Finally, what resources will be required todeliver/undertake activities (money, time,equipment, facilities)?Be sure that your road map is as specific as possiblewhen it comes to the types of activities planned,evidence of services provided and the outcomesyou expect to achieve. A road map that includes thenecessary detail will help you to develop a thoroughproject plan and drive the evaluation processbecause the items you need to evaluate and theirmeasures are already identified. For detailedguidance on this approach to project planning, take alook at Appendix A.© <strong>sports</strong> <strong>coach</strong> <strong>UK</strong>

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>19Section 4Management and Coordination© Alan EdwardsIn this section, we will look to define the roles and responsibilitiesof the key individuals/departments involved in your programme, toensure the infrastructure you have in place is fit <strong>for</strong> purpose. Inaddition, a variety of policies and procedures intended tosafeguard you, your mentors and mentees are outlined. Thesepolicies may be adopted from existing organisational ones ordeveloped specifically <strong>for</strong> this programme. We close by identifyingsome of the insurance considerations you may need to beaware of.Structure and infrastructureNo doubt there will be a range of reporting andaccountability requirements placed on your project,and you will probably be required to utilise thestructure and processes advocated by your fundingproviders or management team. To ensure you havethe best opportunity <strong>for</strong> success, it is important yourecognise this and consider how this may affect thefollowing elements:• management structure• accountability• decision making• funding• aims and objectives• roles and responsibilities.Who does whatThis can vary greatly depending on the size of yourorganisation and the type of mentoring or <strong>coach</strong>support service you intend to offer. However, theroles and responsibilities <strong>for</strong> most activities/taskswithin successful programmes will fall within thefollowing four areas:• project sponsor• project management committee• programme coordinator• programme improvement group.

20<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>Project sponsor(eg finance director)4Project managementcommittee(eg project coordinator plustwo or more stakeholders)<strong>Programme</strong> coordinator(eg allocated role)<strong>Programme</strong> improvement group(eg focus group of stakeholders)It may well be that the above functions areper<strong>for</strong>med by only one or two people if it is a smallprogramme or capacity within your organisation isconstrained. Do not assume that four separatepeople/groups are needed to carry out the roles.However, there is a lot of work here <strong>for</strong> only a fewpeople to do!Project sponsorThis person will often be the budget holder anddecision maker, accountable to stakeholders <strong>for</strong> thebudget and overall success of the programme. Theirroles and responsibilities often include the following:• project set-up:– working with stakeholders to assess the need<strong>for</strong> the project and building a business case– setting specific objectives against which theprogramme will be measured• project awareness:– promotion of the programme both internallyand externally– developing a positive level of interest andsupport <strong>for</strong> the project from stakeholders• staff recruitment (these may bevolunteer posts):– employing/allocating a programmecoordinator to oversee the project delivery– supporting the recruitment of support staff,including mentors• accountability:– establishing a ‘management team’ to sign offthe programme milestones– responsible <strong>for</strong> the overall governance ofthe project.Project management committeeResponsibility <strong>for</strong> overseeing the project may behanded over to a ‘management team’ broughttogether by the project sponsor. This group exists torepresent your interests (and those of the serviceyou provide), as well as mentees and mentors. Itprovides strategic direction and ensures theprogramme is managed according to its intendedoutcomes. However, the management team doesnot become involved in the day-to-day activities. Acomprehensive committee/group may consist of thefollowing individuals:• trustees, board members, committee members• core delivery staff (programme coordinator)• service users (mentee)• skilled practitioners (mentor)• partner organisations (eg training providers)• consultant advisers (experts in the field).

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>21However, this group may be as small as three people– the programme coordinator, an experiencedmentor and a mentee. While small can be good andoften more responsive to change/decision making,we would not recommend that this role becomethe responsibility of one individual.<strong>Programme</strong> coordinatorMost successful mentoring programmes aremanaged by a designated member of staff who has aproportion of their time ring-fenced specifically <strong>for</strong>this work. They have responsibility <strong>for</strong> theoperational day-to-day delivery of the project in linewith the project objectives. This is a crucial roleand involves:• implementing the goals and objectives ofthe project• managing, developing and coordinatingthe project• developing and working within the budget overtime, keeping full financial records• working with third party consultants and trainingproviders, where required• marketing the programme• identifying suitable mentors and mentees <strong>for</strong>the programme• recruiting mentors and mentees and providingfollow-up support• developing activities <strong>for</strong> the programme,including orientation, training, matching, and theclosing of the programme• maintaining a database of mentors and mentees,and mentoring pairs• ensuring the relationships between mentors andmentees are sustained, and sustaining their ownrelationship with mentors and mentees• identifying any potential risks that may occurthroughout the programme and providingappropriate solutions• maintaining records (qualitative andquantitative data) <strong>for</strong> review, evaluationand planning purposes.This person will require a high level of personal andsocial skills in dealing with a diverse group ofindividuals, from management to volunteers.Depending on the size of the programme andbudget available, it is possible that the projectcoordinator could be further supported by thosewithin administration, training andrecruitment teams.<strong>Programme</strong> improvement groupYou may find it helpful to establish an in<strong>for</strong>malprogramme advisory group made up of mentorsand mentees on the programme. This group canhelp align the day-to-day operation and delivery ofthe programme to better meet their needs. As a<strong>for</strong>um <strong>for</strong> the suggestion of new ideas, ways ofworking and programme improvement, their mainfunctions would include sharing:• experiences of the programme, highlightinggood practice and areas <strong>for</strong> development• impact and feedback based onprogramme activities.Policies and proceduresWe recognise that the paperwork associated withprogramme policies and procedures can beoverwhelming. Nevertheless, they are veryimportant and central to the safe and effectiverunning of your project. These policies andprocedures are intended to safeguard you, yourmentors and mentees so while you may wish tolimit these to what is essential, they must be fit <strong>for</strong>purpose. Where relevant, it is recommended thatyou have in place policies relating to the following:protection ofvulnerable adultsdiversity andequalitychild protectionpersonal safetyand lone workinggrievance andcomplaintsdata protectionand confidentialityThese policies may be adopted from existingorganisational ones or developed specifically <strong>for</strong> thisprogramme. When creating these, it is important toconsider the employment status (volunteer, paid,self-employed) of your mentors and how this mayimpact on the policies and procedures you putin place.4

22<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>4Child protectionYou have a legal obligation to safeguard and protectany children and young people with whom your staf<strong>for</strong> volunteers come into contact. All sportingorganisations that provide a service <strong>for</strong> children andyoung people must ensure that:• the welfare of the child is paramount• all children, whatever their age, culture, disability,gender, language, racial origin, religious beliefsand/or sexual identity have the right toprotection from abuse• all suspicions and allegations of abuse and poorpractice are taken seriously and responded toswiftly and appropriately• all staff (paid/unpaid) understand they are legallyobliged to report to the appropriate officer anyconcerns they have about a child• the correct procedures on Disclosure andBarring Service (DBS) checks (<strong>for</strong>merly CriminalRecords Bureau) are followed.The policies that you develop and the proceduresthat govern how they are applied will be in<strong>for</strong>medby the requirements of the followinggovernment legislation:• Protection of Freedoms Act 2012• Children Act 2004• Education Act 2002.Note: Your child protection policy is likely to impacton a number of areas within the programme (seebelow). There<strong>for</strong>e, all mentees and mentorsassociated with the project must be made aware ofthe policy and its implications <strong>for</strong> their role.• Confidentiality – Procedures are in place <strong>for</strong>the breach of confidentiality should a child oryoung person be at risk.• Recruitment – Screening and selection take intoaccount policy requirements in relation toDBS checks.• Training – Disclosure, confidentiality andrecognition of abuse should be considered aspart of mentor training.• Mentor/mentee matching – This should ideallyoccur only once full recruitment checks,including receipt of a DBS check, havebeen completed.• Meetings – These are to occur in a suitableenvironment appropriate <strong>for</strong> the interventionin question.• Support – Ongoing contact should bemaintained with all parties and the relationshipmonitored accordingly.7www.nspcc.org.uk8www.thecpsu.org.uk9www.sportandrecreation.org.uk/smart-sport/safeguarding-vulnerable-adultsBe<strong>for</strong>e looking to develop a safeguarding policy,contact your governing body of sport as it mayalready have a policy and procedures in place thatyou can adapt to suit your needs. The NSPCC 7 andCPSU 8 have a number of resources that will assistyou in developing a safeguarding policyand procedures.The <strong>sports</strong> <strong>coach</strong> <strong>UK</strong> workshop ‘Safeguarding andProtecting Children’ includes specific details of codesof practice when <strong>coach</strong>ing children and providesother valuable in<strong>for</strong>mation in this area. To find outmore and book a place, visit www.<strong>sports</strong><strong>coach</strong>uk.organd click on ‘Workshops’.Protection of vulnerable adultsAny organisation working with vulnerable adultsshould have in place appropriate policies andprocedures to protect them from potential abuse.The policy should include:• the scope of the problems being addressed• structures <strong>for</strong> planning and decision making• the principles to be upheld• a warning about the scale of the risk of abuse ofvulnerable adults and the importance ofconstant vigilance• a definition of abuse, setting out currentknowledge, based on the most recent researchon signs/patterns of abuse and features ofabusive environments• a definition of those vulnerable adults towhom the policy, procedures and practiceguidance refer.Training should be provided on the policy,procedures and professional practices that are inplace locally as well as responsibilities <strong>for</strong> theprotection of vulnerable adults.The <strong>Sport</strong> and Recreation Alliance, its steeringgroup, and the English Federation <strong>for</strong> Disability<strong>Sport</strong> (EFDS) have all developed useful resources toensure all <strong>sports</strong> organisations are aware of theimplications and practices surrounding theprotection of vulnerable adults 9 .Data protection and confidentialityIf you handle personal in<strong>for</strong>mation about individuals,you have a number of legal obligations under theData Protection Act 1998 to protect thatin<strong>for</strong>mation. You will need certain processes in placeto ensure the safe keeping of this in<strong>for</strong>mation. TheAct applies to ‘personal data’, in<strong>for</strong>mation fromwhich an individual can be identified (eg names,addresses, contact in<strong>for</strong>mation, employment history,medical conditions, convictions). The Act containseight ‘data protection principles’.

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>23These specify that personal data must be:1 processed fairly and lawfully2 obtained <strong>for</strong> specified and lawful purposes3 adequate, relevant and not excessive4 accurate and up to date5 not kept any longer than necessary6 processed in accordance with theindividual’s rights7 securely kept8 not transferred to any other country withoutadequate protection.Specific provision is made under the Act <strong>for</strong>processing sensitive personal in<strong>for</strong>mation. Thisincludes racial or ethnic origin, political opinions,religious or other beliefs, trade union membership,physical or mental health condition, sex life, criminalproceedings or convictions. This type of data issubject to special rules and requires explicit consentfrom the individual concerned be<strong>for</strong>e it canbe processed.In summary, the Act requires you to collect and usein<strong>for</strong>mation fairly, store it safely and not disclose it toany other person unlawfully.With regard to confidentiality and disclosure, this canbe expressed by the following three principles:1 Individuals have a fundamental right toconfidentiality and privacy of in<strong>for</strong>mation.2 Individuals have a right to control access to, anddisclosure of, their personal in<strong>for</strong>mation bygiving or withdrawing consent.3 When considering whether to discloseconfidential in<strong>for</strong>mation, staff should have regard<strong>for</strong> whether the disclosure is necessary,proportionate and accompanied by anyundue risk.Use or disclosure of in<strong>for</strong>mation is only justifiedwhere consent has been given, there is a statutoryrequirement to use or disclose in<strong>for</strong>mation and/orthe balance of public and private interest favoursdisclosure. There<strong>for</strong>e, it is important that you createa confidentiality policy and perhaps someawareness-raising training that considers:• disclosure of in<strong>for</strong>mation relating to membersof staff• disclosure of in<strong>for</strong>mation relating to clients• record keeping and managing records• implications <strong>for</strong> all staff and participants withregard to disclosure and confidentiality.Personal safety and lone workingYou have a responsibility or duty of care <strong>for</strong> thepersonal safety of those working within yourprogramme. While this does not mean you must riskassess every situation, it does mean you have aresponsibility <strong>for</strong> assessing, avoiding and controlling<strong>for</strong> any global risk associated with programmeactivities. However, this is not at the expense of anindividual’s own responsibility <strong>for</strong> their welfare andthe welfare of those with whom they are working.They too must take reasonable care of themselvesand those affected by their work.Lone working is any situation or location in whichsomeone works without a colleague nearby or is outof sight or earshot of another colleague. There<strong>for</strong>e,lone workers may be vulnerable and at increasedrisk of physical or verbal abuse and harassmentbecause they don’t have the immediate supportof others.The policy produced should provide advice to assiststaff/mentors and managers in dealing with loneworking, in particular, to stress the need <strong>for</strong> robustrisk assessment and risk management by all in loneworking situations.The policy should in<strong>for</strong>m lone workers about thearrangements in place to protect themselves andshould clarify roles and responsibilities in theeffective implementation of control measures. Thepolicy should also state the actions that will be takenfollowing incidents. The policy should becommunicated to all lone workers, throughinductions, training or team meetings. For morein<strong>for</strong>mation on the hazards associated with loneworking, visit the Health and Safety Executive (HSE)website: www.hse.gov.ukDiversity and equalityThe Equality Act 2010 (Amendment) Order 2012now captures much of the legislation relating toequal opportunities that may impact on the policyyou develop. This policy should set out how yourorganisation intends to tackle discrimination andpromote equality and diversity in areas such asrecruitment, training, management and pay.A policy might include:• statements outlining your organisation’scommitment to equality• identification of the types of discrimination thatan employer (and, if this applies to you, a serviceprovider) is required to combat across theprotected characteristics of age, disability, genderreassignment, marriage and civil partnership,pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief,sex, and sexual orientation4

26<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>4Insuring your activities – thingsto remember• When purchasing insurance, it is important tobear in mind that volunteers may not beautomatically considered a ‘third party’ <strong>for</strong> thepurposes of public liability insurance. There<strong>for</strong>e,it is important that your insurers specificallyrefer to volunteers in insurance policies (egemployer’s liability insurance should coveremployees and volunteers).• Insurance policies should cover all actionscarried out by paid staff and volunteers and listall the types of venue where these actions arecarried out (eg mentoring in people’s homes,observing <strong>coach</strong>ing in a swimming pool). Youmay wish to consider holding an annual reviewwith your insurance company to discussactivities that are planned <strong>for</strong> the coming yearand check whether existing policy coveris adequate.• If those involved regularly take part in strenuousor potentially dangerous activities (eg <strong>coach</strong>ingadventure <strong>sports</strong> or using specialisedequipment), then be sure that these activitiesare covered in your policy.© <strong>sports</strong> <strong>coach</strong> <strong>UK</strong>

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>27Section 5Operation andImplementationGetting mentee and mentor recruitment right is extremelyimportant. There<strong>for</strong>e, this section attempts to provide somestep-by-step guidance to help you. Advice on where to findmentors and mentees is provided, along with example eligibilitycriteria (how you will decide who you will and won’t be able tosupport). Within this stage of your programme implementation,you also need to design/develop an orientation, which outlineswhat the programme is about, what mentors and mentees willget from it and what commitment you require – stressing thisis important.Mentee recruitmentWhere will the mentees come from? How will theybe identified and referred to you? What referralsystem do you have in place? What are youreligibility criteria?An example referral systemKey considerations:• Be clear on what you expect of mentees(what you expect them to do/commit to,eg time and activities).• Identify your target group (it may help to createa profile of the ideal person).• Consider the best method to reach them(leaflet, flyer, posters), advertise in local media,use websites, press releases, personalrecommendations, presentations at upcomingevents, social media and newsletters (get peopletalking about it).• Post adverts on relevant <strong>coach</strong>ing-relatedwebsites.• Approach specialist organisations and charitiesto ensure you are reaching as wide a networkas possible.

28<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>5Be clear onwhat youexpect ofmenteesIdentify yourtarget groupConsider thebest methodto reach themPost adverts onrelevant<strong>coach</strong>ing-relatedwebsitesApproach‘specialists’ toensure yourreach is wideBe creative about the recruitment process; gobeyond your current network. Keep the in<strong>for</strong>mationconcise, simple and avoid using jargon. Are you usinginclusive imagery to market to a diverse population?Where referrals are made to your project throughan external person/body, make sure that you collectall the necessary in<strong>for</strong>mation:• referring person/organisation name, position andreason <strong>for</strong> referral• client name, address, contact details, date ofbirth and sex.This will be good in<strong>for</strong>mation to obtain, especiallywhen reflecting on where your mentees came fromas part of your monitoring and evaluating process.Example eligibility criteria• be able to obtain parental/guardian/carerpermission and/or ongoing support <strong>for</strong>participation in the programme if under the ageof 18 years or regarded as a ‘vulnerable adult’• be willing to complete any relevantscreening procedure• agree to attend mentee training as required• be willing to communicate regularly with theprogramme coordinator and discuss progress.The criteria you choose should be driven by theprogramme’s aims and outcomes. Being clear aboutthe focus of the programme will help you definewho exactly your target audience is. You willthere<strong>for</strong>e be able to identify your ‘ideal’ candidatemore easily. Not all of these criteria will be relevantto your programme, and this is not an exhaustive list.Prospective mentees must:• be overtly willing to commit to be part of theprogramme (eg two hours per month); specifythe minimum amount of time the person mustcommit to the project• meet the programme’s age criteria (eg youngpeople [16–18], adults [18+] or targeted at aspecific age group [50–65]); be aware that youwill need to give reasons if you are specifying anage group• pledge to engage in a two-way relationshipwith an allocated mentor (over a defined periodof time)• be motivated to work toward positive growth(which may include change to existing practices)• be willing to engage in group tasks and activitieswhere appropriate• hold or be working toward a <strong>coach</strong>ingqualification (eg at Level 1, 2 or 3)• live within x miles of, or live within, aparticular borough• be willing to abide by all programme policiesand procedures

30<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>5Once you have identified the profile of your targetgroup, consider why they may wish to join yourprogramme and what it is that will draw them in –this will become your key marketing tool. Thefollowing process should help get you on the rightpath to attracting the right people:1 Decide what type of person you want.Describe them, perhaps through a shortnarrative (their behaviours and actions) or, ifappropriate, a detailed job description (detailingduties) and person specification (detailingexperiences). The National OccupationalStandards (NOS) <strong>for</strong> Coaching and <strong>Mentoring</strong>are a good starting point. Advertising <strong>for</strong> aspecific role is more likely to attract the rightpeople. Be careful not to say who you don’twant as this will not reflect well on yourprogramme or your organisation.2 Identify what will draw them to yourprogramme. Is it the thought of payment orrecognition as a valued <strong>coach</strong>/practitioner intheir field? Is being associated with yourprogramme a positive career move and seen asincreasing their credibility? Do they simply wishto re-invest in the future of <strong>coach</strong>ing?Understanding their motivations is importantas this will help in tailoring your recruitmentstrategy and provide a clear recruitmentmessage.3 Where can you find potential mentors? It isimportant that you do not simply launch into animmediate recruitment campaign either using ablanket approach (trying to appeal to everyone)or targeting the same sources as be<strong>for</strong>e. It isrecognised that mentoring is a skilled role, andyou will probably need to go beyond yourtraditional contact database. There<strong>for</strong>e, take timeto consider who the appropriate people couldbe. What sort of groups do they come from(business, community groups, voluntary sector,retired work<strong>for</strong>ce, eg teachers)? Are theyexisting <strong>coach</strong>es within clubs?Note: Ensure you are aiming to meet a truerepresentation of the community with thisprogramme to make sure you have a diversemix of skills, abilities and experiences. This willinevitably make your matching process easierand ensure your mentees get a more roundedexperience. This will enhance the programme’scredibility and improve your ability to focus onthe needs of your target group.4 How can you reach them? Once you have abetter idea regarding who your potentialmentors are and where they may reside, youcan be much more focused in the method youuse to reach them. A variety of methods willencourage diversity in applicants, hopefullyreflecting the social composition of thecommunity within which your programme willoperate. Promotional methods include:– leaflets and flyers (targeted drops)– advertisements in local media (magazines,newspapers etc)– use of websites (CoachWeb, governing bodyof sport, CSP etc)– direct contact with local, regional andnational companies– press releases (in a variety of media, includingeBulletins)– recruitment fairs or similar events– open events/inviting those recommended togroup sessions– utilising links with higher education(HE)/further education (FE) institutions asthey often have motivated volunteers– visiting local <strong>sports</strong> clubs, activity groupsand associations.Use any past experience you have. Contact past orexisting mentors and mentees as they will know thesystems and should be good advocates <strong>for</strong> your newprogramme. Finally, word of mouth is the mostcommonly used method of recruitment. Make sureeveryone you know is aware of the programme andthe type of person you are looking <strong>for</strong>, and that theytell other people!Keep the in<strong>for</strong>mation you provide simple. Avoid theuse of jargon and abbreviations where possible.These can be quite off-putting to the reader and arenot accessible to everyone. As a general rule, yourpublicity material should include the following:• the purpose of this mentoring programme andhow it will operate• the length of the programme• mentors’ commitment in terms of timeand activities• the training and ongoing support offered• the key phases of a mentoring programme• what they need to do to get involved• who the main point of contact is.Remember – advertise in places the ideal candidatewould go!Application processYou may wish to use a <strong>for</strong>mal application <strong>for</strong>m or asimple expression of interest. Whichever it is, be sureyou gather the details you need to make anin<strong>for</strong>med decision regarding their suitability. Try to

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>31Mentor recruitment<strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> RecruitmentMentee recruitment5Open invite through parallel advertsSelection/screeningApplicationEligibility checkInitial trainingOrientationTraining needs analysisMatching/Pairinguse a method that, while meeting your needs, doesnot overburden potential applicants and is accessibleto all applicants. For example, don’t advertise thatapplications can only be made in writing – be opento verbal or written applications. The applicationprocess is as much about the applicant choosing tobe part of the programme as it is about youdeciding if you want to recruit them.In<strong>for</strong>mation packs can be helpful in providing furtherdetail about the programme. Here, you can describein more detail the aims and outcomes. The mentorrole can be described more thoroughly, along withany training offered, ongoing support and dates <strong>for</strong>meetings. Here, you can also make clear the level ofexperience and qualities you require through some<strong>for</strong>m of selection criteria – <strong>for</strong> example:• two or more years of experience as a mentor(in the field of <strong>sports</strong> <strong>coach</strong>ing)• knowledge of their sport and an ability toshare it• a track record of supporting <strong>coach</strong> learningand growth• hold a <strong>coach</strong>ing qualification at Level 2 or above(in a particular sport)• having time to commit to the programme(4–6 hours per month)• good interpersonal/communication skills• familiarity with various mentoring techniques(such as GROW)• the characteristics of lifelong learning• relevant mentoring behaviours to support<strong>coach</strong> learning• being a skilled reflective practitioner• having the potential to per<strong>for</strong>m the followingduties with training:– observe and provide feedback on<strong>coach</strong>ing practice– share teaching and learning strategies,ideas etc– model good <strong>coach</strong>ing practice.Selection criteria are often a combination of themost pertinent elements of both the job descriptionand person specification. Obviously, your selectioncriteria will be specific to the needs of yourprogramme and should there<strong>for</strong>e changeaccordingly. Be aware that if your criteria are toospecific, technical or inflexible, this will restrict thenumber of applicants you get. You may be putting offa perfect candidate if your criteria are too specific.Try to find the right balance.

32<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>5Mentor selection and screeningWhile identifying mentors is not an easy process, it ishoped that the criteria on the previous page willhelp to guide your selection. On receipt ofapplications/expressions of interest, you have thedaunting task of sifting through these and selectingthe applicants who most appropriately match theneeds of the programme. Refer back to yourselection criteria as a starting point – this, along withany job description and person specification youhave used, will act as a great guide to narrow downthe applicants.If you happen to receive many applications, it isuseful to adhere strictly to the criteria you haveoutlined to find your best matches. However, ifsomeone is only missing one or two of the requiredskills or attributes you have identified, don’t assumethat they would be no good <strong>for</strong> the role. Somepeople are not as good as others at filling out <strong>for</strong>msor ‘selling’ themselves. Personality is a massive part ofmentoring and cannot be measured byan application.At this point, you will perhaps have three piles ofapplicants: those who are perfect <strong>for</strong> the role andcan be moved on to the next stage of selection;those who miss out on a few skills listed andperhaps, at face value, may require further training(which you may be able to provide); and thosewho are not right <strong>for</strong> your programme(<strong>for</strong> various reasons).It is important that you take care with the latter twogroups. It is courteous to respond to applicantswhere possible, explaining that, at this point in time,they do not have the desired skills or attributes <strong>for</strong>the programme. You may wish to offer advice onwhat they may do to close any skill/knowledge gaps.These may be valuable applicants to futureprogrammes, and you do not want to alienate themby simply ignoring them.To interview or not to interviewInteracting with potential candidates in a groupsetting is an excellent way to see their character,level of interest, working knowledge of the area andcommunication skills. It also allows you to see if theyare a good fit <strong>for</strong> your programme.Inviting candidates to an open event is also a greatway to encourage self-selection. Only those who aretruly motivated to be part of the programme willfind their way there. Non-attendance without priorwarning can be a useful indicator!Interviews can be conducted in different ways, butthe fundamental premise is to discover which peopleare best placed to work within your programme. Trysetting up various activities that will give you a betteridea of each person’s knowledge of and motivation<strong>for</strong> the role, as well as their personality.If you intend to interview applicants individually,while needing to be structured, the interviewsshould still be quite in<strong>for</strong>mal. Things you need to findout include:• What are their motivations <strong>for</strong> applying?• What do they hope to gain fromthe experience?• What is their understanding of the target group?• Are they being realistic about their availability?• What resources might they need to supportthem in their role?• What kind of additional support might theyneed to fulfil their role?Whichever approach you take, ensure applicants areclear about the purpose and demands of theprogramme, such as:• project aims• activities they are expected to engage in• the profile of the types of mentee they will beworking with• training and ongoing support provided• time commitment (frequency and duration ofinterventions)• resources/tools available to support them intheir role.This sort of in<strong>for</strong>mation should be included withinany mentor in<strong>for</strong>mation pack you create.It may be relevant <strong>for</strong> you to obtain references ortestimonials. These can add confidence to anydecision you make and build a broader picture ofapplicants. A probationary period may also beappropriate, depending on the type of programmeyou are delivering.ScreeningThe safety of the mentor or mentee within yourprogramme should be at the <strong>for</strong>efront of your mindduring the screening process, especially if you areworking with young people or vulnerable adults. Youneed to have an assurance that the safety of bothparties is protected. A thorough screening processappropriate to the age and vulnerability of thoseinvolved in your programme will go a long way toensuring confidence in your scheme.

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>33A thorough application process <strong>for</strong> mentors andmentees may include the following:• Criminal records – Under the Rehabilitation ofOffenders Act, ex-offenders normally have theright not to reveal old/spent convictions.However, where work involves contact withvulnerable populations (children or otherwise),you can request applicants disclose these.• DBS checks – Some roles will be eligible <strong>for</strong>enhanced criminal records checks. These areposts in regulated activity involving substantialcontact with, and responsibility <strong>for</strong>, childrenand/or vulnerable adults. For these posts,criminal records checks should be conductedthrough your governing body of sport oremploying organisation’s procedures. If suchprocedures are not in place, you can obtainmore details from:– the DBS (England and Wales)– Disclosure Scotland (Scotland)– AccessNI (Northern Ireland).Note: Any personal in<strong>for</strong>mation that is disclosed toyou as part of this process must be treated in thestrictest confidence and handled in accordance withthe principles of the Data Protection Act. You shouldalso have a clear confidentiality policy outlining howin<strong>for</strong>mation will be stored and whom it may beshared with. All mentors/mentees must be madeaware of this from the outset.5If an individual is working in regulated activity,the DBS will also check whether they are on itsbarred list, of individuals barred from workingwith children and/or vulnerable adults. Thedefinitions of regulated activities are available onthe Home Office website –www.homeoffice.gov.uk – and are based aroundthe frequency and intensity of responsibility <strong>for</strong>children and young people.• Self-declaration – The candidate should give acommitment to work within the ethos, policiesand procedures of the programme, maintain apositive approach to working practices andcommit to personal development, monitoringand review.Potential participants (mentor or mentee) shouldnot begin working until satisfactory checks havebeen made. While DBS checks are a valuable tool inthe protection of vulnerable groups, they shouldnever be regarded as the only safeguard. These needto be carried out along with other screeningelements you deem appropriate, such as interview,observation of practice, references and probationaryperiods. It may also be the case that a DBS checkidentifies a conviction that has no relevance andshould have no effect on the ability of the mentorto carry out their role. Use the disclosedin<strong>for</strong>mation intelligently.© Alan Edwards

34<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>1

<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>35Section 6Training and<strong>Programme</strong> DeliveryWith the programme up and running, mentees on board andmentors raring to go, it is important this stage gets due time andconsideration. Some of what you developed <strong>for</strong> the menteeorientation may be replicated here, and to that effect, you maywish to run these as parallel events. An additional focus <strong>for</strong> thissection is the training of mentors, ensuring they have a clear viewof their role and the purpose of their relationships. We conclude byhighlighting the importance of ongoing support and contact.Mentor orientation and trainingIt is important that you dedicate time to theorientation and training of your mentor work<strong>for</strong>cein order that they are fully prepared <strong>for</strong> their role.Ill-in<strong>for</strong>med or poorly trained mentors with theirown agenda can be detrimental to the project. Alsobe aware that the people who volunteer to bementors may not always be the people you want.Getting this part right will ensure you can offer agood quality service.OrientationThe orientation event should focus on integratingmentors into the programme and developing theirawareness of its aims, as well as giving you anopportunity to manage expectations, respond toquestions and deal with any concerns.It may be relevant to conduct the orientation aspart of the selection and screening process. Duringthe session, you should attempt to identify the needsof your prospective mentors in relation to thedemands of your programme. This in<strong>for</strong>mation willbe invaluable to the development of your initialtraining (and ongoing support). As a general rule, thefollowing would be relevant topics to cover:• background to the programme, why it cameabout and what it is intended to achieve• benefits and rewards both <strong>for</strong> mentor andmentee (eg training, payment, bursaries,CV enhancement)• background and circumstances of the targetgroup (who they are, where they are from, whatthey may want)

36<strong>Creating</strong> a <strong>Mentoring</strong> <strong>Programme</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sport</strong>6• opportunities to express expectations, concernsand expected challenges (and ways toovercome these)• key policies and procedures with regard to theoperation of the programme (perhaps includinga code of practice)• project team, key contacts and support availablefrom them• commitments required from all involved (time,activities, personal development etc)• nature of the mentoring relationship (<strong>for</strong>mal,in<strong>for</strong>mal, structured, ad hoc etc).You will need to tailor your mentor orientation tothe specific demands of your programme, and youmay even wish to deliver it alongside an orientation<strong>for</strong> the mentees. Bring the two groups together atpertinent points during the session (eg expectations,concerns, code of practice, nature of relationship).Doing this will enable them to develop a sharedunderstanding <strong>for</strong> the programme.TrainingYour applicants will come from a wide and diverserange of backgrounds and experience. Someindividuals may have been practising <strong>for</strong> years insimilar roles, whereas others may be new to this<strong>for</strong>m of <strong>coach</strong> support. We would suggest that yourtraining should cover the areas in the diagram below.Take an interactive approach to delivering thetraining, encourage participation by all, and value theexperiences of those in attendance – these canoften be your most useful resource. Training shouldcontain a good balance of practical activities wherementors can experiment with some of the skills,techniques and tools relevant to the mentoring role,as well as whole and small group tasks that challengetheir thinking. An element of supported or individualreflection is also valuable – often, this is the mostdifficult to master.At this stage, it may be relevant to hand out copiesof the project handbook/resource. This can act as areference guide and may combine an overview ofthe programme, a training resource and a policydocument. Example content is outlined below:Policy and ProcedureChild protectionProtection ofvulnerable adultsData protectionand confidentialityPersonal safety andlone workingDiversity and equalityGrievanceand complaintsInsuranceExpensesTraining Toolsand TechniquesThe role of the mentorBuilding relationshipsand rapportManaging mentoringrelationshipsEssential skills<strong>for</strong> mentoringProfiling andaction planningLearning preferencesReflectionon experienceGrowing as a mentorSupervision and support Example: GROW Model,ADKAR Model<strong>sports</strong> <strong>coach</strong> <strong>UK</strong>, Coachwise Learning and 1st4sportQualifications offer a variety of products that may behelpful in the training and development of mentors.Outline the roleof the mentor inthe developmentof <strong>coach</strong>esExplain how to identifyimportant learningopportunities <strong>for</strong><strong>coach</strong>esExplain how a mentorcan help to maximisethese learningopportunitiesDevelop a personalmentor profile anddevelopment planIdentify and practisethe core skillsof mentoringManage theself-reflection,<strong>coach</strong> profiling anddevelopment planning